Abstract

Despite increasing egalitarian values expressed among college students, dating is still characterized by traditional gender roles. Because traditional dating scripts are predominantly recited and enacted to the extent that men initiate and pay, there are assumptions that the sexual processes have not changed. This study investigates the sexual processes of male-initiated and female-initiated dates among college students in the US. Using data from the Online College Social Life Survey, we ask whether traditional components of the dating script explain traditional sexual outcomes (non-genital contact), as well as whether alternative dating scripts explain nontraditional sexual outcomes (genital contact). Using multivariate logistic regression models, we found that violations of the traditional script are associated with higher odds of genital contact for male- and female-initiated dates; however, the predictors of genital contact for female-initiated dates are not the same as those for male-initiated dates. This study highlights the variability of sexual scripts in dating practices, suggesting that the sexual scripts associated with dates are not as homogenous as we have previously believed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last two decades, hookup culture has expanded the boundaries of normative sexuality and introduced casual sexual interactions (i.e., “hookups”) as a distinct pathway for relationship development (Allison, 2019). Dates and hookups can be understood as “two sides of the same coin” in the American courtship process, as they both carry the potential to lead to a relationship (Luff et al., 2016:76). Despite the flexible placement of sex in the courtship process, recited dating scripts remain traditionally gendered and sexually conservative. The traditional dating narrative states that men initiate, plan, and pay for dates. Sexual activity is involved, but not beyond kissing and potentially groping. Within this narrative, men initiate most of the sexual activity and women make sure the sexual activity stays within the parameters of respectability (Bartoli & Clark, 2006; Laner & Ventrone, 2000; Morr & Mongeau, 2004). This dating narrative reflects a culturally-determined script for appropriate behavior in the dating context.

Sexual Scripts

Sexual scripting theory conceptualizes “the sexual act as being a negotiated outcome,” taking place on three interrelated levels: the cultural, the interpersonal, and the intrapsychic (Simon, 2005:294). Sexual scripts function as “blueprints” for appropriate behavior on the cultural level that influence how individuals “choos[e] a course of action and evaluat[e] behaviors already performed” on the interpersonal level (Rose & Frieze, 1989:258). On the intrapsychic level, scripting of one’s innermost desires and motivations takes place, speaking to the fact that “individual desires are linked to social meanings” (Simon & Gagnon, 1984:53).

In the context of dating, the cultural script dictates who asks, who pays, who initiates the sexual activity, as well as when, where, and how much sexual activity is appropriate. On the interpersonal level, negotiations are made between an individual’s intrapsychic desires and society’s expectations for proper behavior in a given cultural scenario (Gagnon & Simon, 2005). In this paper, we examine the sexual outcomes of dates as part of a scripted process, which allows us to assess how sexual processes in dates compare between the cultural script and reported practices, which reflect negotiations made on the interpersonal and intrapsychic levels. This is important because “[s]ites of ‘disjuncture’ between cultural and inter- or intrapersonal sexual scripts are a particularly promising location for the study of change in sexual scripts” (Masters et al., 2013:410).

Historical Context of Traditional Dating Scripts

The heterosexual dating script recited today originated in the early twentieth century when the dating system became the dominant courtship norm. At this time, gender roles were shifting as young, single men and women started socializing with each other in public spaces. Dates took place at dance halls, movie theaters, and other venues of commercial entertainment, all of which required money that men had and most women didn’t. Dates, then, relied on men’s money, which gave men control over date initiation and made them feel “entitled” to seek sexual compensation from women (Bailey, 1988:21). The early-twentieth century dating script, then, consisted of men asking women on a date, men paying for the night’s activities, and then men initiating sexual activity. Women were tasked with receiving men’s advances and limiting the amount of sexual activity that took place (Bailey, 1988; Spurlock, 2016).

In the 1920s, sexual activity in the form of necking and petting—“caresses above the neck” and “caresses below”—were “customary” and “expected elements” of any date as part of what women “owed” to men for financing the night’s activities (Bailey, 1988:80, 81). Importantly, however, many women took advantage of this customary practice to explore their own sexual desires in “respectable” ways (Littauer, 2015). Activities beyond necking and petting, such as those involving genital contact, were still conventionally reserved for marriage and would put a woman’s reputation at risk if she were to go “too far” (Bailey, 1988; Spurlock, 2016; Syrett, 2009). In other words, necking and petting were part of the twentieth-century dating script, but genital contact was not, because women risked losing their respectability. Women walked a fine line, as they were responsible for limiting sexual activity, but they were also expected to compensate men for financing their dates.

Contemporary Dating Scripts

In many ways, the extant literature suggests that the contemporary dating script looks strikingly similar to the script from over a century ago, despite increasing egalitarian views expressed by young adults. This script dictates that men initiate and pay for dates, and women limit whatever sexual activity is initiated by men. This sequence of behaviors has been reported consistently by scholarship over the last 30 years (Bartoli & Clark, 2006; Cameron and Curry, 2020; Laner & Ventrone, 1998, 2000; Morr Serewicz & Gale, 2008; Rose & Frieze, 1989, 1993; Seabrook et al., 2017). Although much of the research on dating scripts has focused on first dates, scholarship on dating practices in general has found that the early stages of the courtship process are characterized by the traditionally gendered script, wherein men take an active role and women remain passive (Bartoli & Clark, 2006; Lamont, 2020; Sassler & Miller, 2011, 2017). Bartoli and Clark (2006) focus specifically on the scripting of “typical dates,” finding traditional gender behaviors are not limited to first-date contexts. Furthermore, despite variation in how relationships progress, Sassler and Miller (2011:490) find “more consistency than contestation with traditional gendered scripts.” Rose and Frieze (1993:500) argue that gender roles “are more operative early in courtship than at later stages,” in part, because “relationship continuation [to exclusivity] often depends on the adequate fulfillment of these roles.”

Ultimately, dates that take place before an exclusive relationship is established seem to follow the traditional dating script. An exclusive relationship is often the point at which the labels “boyfriend” and “girlfriend” are introduced and a couple becomes “officially” monogamous. Importantly, exclusivity requires an explicit conversation, as exclusive relationships are “formed through verbal discussion of relationship status, or ‘the talk’” (Allison, 2019:371). Dates, on the other hand, are not always accompanied by a conversation to define the interaction. As such, individuals rely on cultural scripts and gender roles to navigate the ambiguity in the early stages of the courtship process (Cameron & Curry, 2020; Rose & Frieze, 1993). For example, scholars have found that women rely on men’s initiation and payment to confirm that an interaction is, in fact, a date and that mutual romantic interest is present (Allison, 2019; England et al., 2012; Lamont, 2020).

Alternative Scripts

While it is conventional for men to initiate dates, it is not unheard of for women to do the same (Mongeau & Carey, 1996; Mongeau & Johnson, 1995; Morr Serewicz & Gale, 2008). In 1993, Mongeau et al. found that most college students reported experiencing at least one heterosexual female-initiated date. Data from the Online College Social Life Survey, collected between 2005 and 2011, shows that 12 percent of dates reported by surveyed college students were female-initiated. Additionally, England et al., (2012:567) reported that over 90 percent of students, including both men and women, “approve heartily of women asking men on dates.”

Female-initiated date processes in the twenty-first century have been largely neglected by scholarship, but Morr Serewicz and Gale (2008) examined whether variations in the traditional script, including gender of date-initiator, would lead to differences in how a first date script was recited. They conclude that “traditional gender roles appear to be alive and well in the scripting of first dates,” while also noting that “female-initiated first dates result in greater complexity in expectations for sexual behavior” (Morr Serewicz & Gale, 2008:161). Their analyses suggest that a female-initiated date signals a different sexual script, but this script has been largely uninterrogated in research on dating scripts over the last 20 years. Because we cannot assume that dates with nontraditional scripts follow the same sexual processes as dates with traditional ones, this study approaches male-initiated and female-initiated dates as separate processes.

Standards for Sexual Behavior

In the 1920s, women were responsible for limiting sexual activity on dates to necking and petting due to the pressures of what can be considered a sexual double standard, wherein women would lose their respectability if they went “too far” (i.e., engaged in genital contact), but men’s reputations would be unaffected. Today, the dominant cultural script dictates that genital contact is not appropriate on a date, but it is unclear if this is also true in practice given the changing circumstances of respectability in contemporary America with the rise of a hookup culture around the turn of the twenty-first century. Hookup culture encompasses a set of values, ideals, norms, and expectations that are part of the system that accepts casual sexual interactions (i.e., hookups) as a feature of, not replacement for, courtship (Heldman & Wade, 2010; Kuperberg & Padgett, 2016; Monto & Carey, 2014; Wade, 2017).

Within the hookup culture context, women can engage in sexual activity beyond “petting” without risking their reputations. This has led to an increasing lack of consensus among scholars regarding whether a sexual double standard still exists and if so, to what extent. In fact, Crawford and Popp (2003:14) describe the “heterosexual double standard” as a “‘now you see it, now you don’t’ phenomenon,” given the inconsistency in empirical evidence supporting its existence. If the influence of the sexual double standard has decreased in the twenty-first century, as some scholarship suggests (Jackson & Cram, 2003; Marks & Fraley, 2005; Milhausen & Herold, 2002; Weaver et al., 2013), then women may not feel compelled to limit sexual activity given their reputations would not be at risk. This may be especially true if men both ask and pay for a date, leaving women to feel like they “owe” something. With that being said, many scholars argue for the continued relevance of the sexual double standard to some extent, either suggesting different ways of conceptualizing it or proposing new methodological approaches to measure it (Armstrong et al., 2012; Farvid et al., 2017; Kettrey, 2016; Reid et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 2020). Lack of empirical evidence aside, it seems that “gender remains central to evaluations of sexual behaviors in at least some contemporary social settings” (Allison & Risman, 2013:1193).

The inconsistencies in reports of the sexual double standard in the twenty-first century may be attributed to the fact that the scripts for appropriate sexual behavior are context dependent. In other words, the operation of the sexual double standard is affected by whether sex takes place within the context of a hookup or a date, which are two distinct cultural scenarios. Reid et al. (2015:189) report a general consensus among college students that sex on a date is “a situational impropriety,” even if the pair has previously engaged in casual sex. In another study, Reid et al. (2011:559) found students described sex as acceptable for women in a hookup context because it signals sexual agency, but within the context of a date, women are expected to “moderate [their] sexuality” to show that they are “dating material.” Other scholars have found that both men and women express losing interest in dating someone who is perceived to be promiscuous, suggesting a conservative single standard for sexual activity in dating contexts (Allison & Risman, 2013; England & Bearak, 2014). The traditional dating script may not have changed much in the last 20 years, but sexual norms and the parameters for appropriate sexual behavior certainly have.

Regarding standards for sexual behavior in contemporary America, there is a distinction to be made between being respectable and being relationship material. Historically, the sexual double standard’s regulation of women’s respectability also regulated whether a woman was considered marriage material. In other words, a loss of respectability corresponded to a loss of relationship prospects. This equation between respectable and dateable no longer holds true in all contexts. We propose that there is a relational standard for sexual behavior, which speaks to the belief that going “too far,” or engaging in genital contact, on a date disqualifies someone from being considered “relationship material.” Although women are held to higher standards and lower benchmarks of how much sexual activity is “too much,” the relational standard also applies to men to the extent that heterosexual women report being less interested in dating men who are perceived to be promiscuous (England & Bearak, 2014; Klein et al., 2019). In sum, the sexual double standard speaks to who can have sex and still be respectable. The relational standard speaks to where sex can happen and still lead to a relationship.

There seems to be a general consensus that the cultural script for dating dictates that dates are not appropriate contexts for sexual activity that involves genital contact (Allison, 2019; Klein et al., 2019; Reid et al., 2011, 2015). Research addressing sexual activity in dating contexts, however, tends to stop with the cultural script and does not entertain the possibility that practices might not align with recited expectations. With that being said, Kuperberg and Padgett (2015:525) found that while sex was more likely to happen in hookup contexts, “one-third of dates [in their sample] included sex.” Certain sexual behaviors, such as oral sex and intercourse, may be considered inappropriate on a date, but in practice, it is not uncommon for dates to involve genital contact. In other words, college students may recite a cultural script with sexually conservative date outcomes, but this does not align with reported practices, which reflect negotiations taking place on the level of interpersonal scripting. Given this inconsistency, this study investigates how sex is being re-scripted on the interpersonal level in dating contexts by examining how genital contact is associated with traditional and nontraditional components of dating scripts and standards of sexual behavior.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Because recited dating scripts are still enacted to the extent that men ask and men pay on most dates, there are assumptions that sexual activity has also remained traditionally conservative. Over the last two decades, there have been dramatic shifts in sexual norms, as evidenced by the incorporation of casual sex alongside dates in the courtship process. Scholarship focuses almost exclusively on the changing sexual norms in the context of casual sexual interactions, not dates. While at the same time, research on dating practices continues to focus on the traditionally gendered behaviors, often overlooking the possibility of changes in the sexual script regarding the extent of sexual activity on dates. In this study, we examine sexual outcomes of dates as part of a scripted process, with consideration for the possible “disjuncture” between a date’s cultural script and its interpersonal one (Masters et al., 2013:410). In doing so, we assess how sexual processes in dates compare between cultural expectations and reported practices.

Our first two research questions examine how sexual practices are associated with script components from a dominant cultural scenario. First, we explore whether traditional components of the male-initiated dating script (men paying; men initiating sexual activity) lead to traditional sexual outcomes. Specifically, which components of the traditional (i.e., male-initiated) dating script explain the likelihood of genital contact on a date? (RQ 1). Because traditional dates are not supposed to involve genital contact, we hypothesize that the likelihood of genital contact will decrease when dates are traditionally scripted—that is when men pay on male-initiated dates. Because women are the “gatekeepers” and men are the pursuers of sex in the traditional dating narrative, hypothesis 1 states that the likelihood of genital contact will decrease on male-initiated dates when men initiate more of the sexual activity compared to when women initiate or when respondents indicate being unsure of who initiated more sexual activity.

Second, we examine the sexual processes of female-initiated dates. Specifically, which components of the alternative (i.e., female-initiated) dating script explain the likelihood of genital contact on a date? (RQ 2). Given female-initiated dates signal a different type of cultural script that has yet to be thoroughly explored, we are interested in identifying the sexual outcomes of these dates in addition to which components of the script are associated with nontraditional sexual outcomes. Hypothesis 2 states that the likelihood of genital contact on female-initiated dates will decrease when women pay for part or all of the date, but it will increase when women initiate more of the sexual activity. Due to the lack of research on female-initiated dates, our hypotheses are exploratory. In one of the only extensive studies of female-initiated dates, Mongeau et al., (1993:66) find that “males tend not to equate a direct date initiation as a direct sexual invitation” despite previous research that suggested otherwise. More recently, Emmers-Sommer et al., (2010:350) speculate that men may be less likely to expect sex when women initiate the date or women split the bill: “when men’s currency of asking and solely paying is absent they perceive that they’ve lost their ‘card to play,’ if you will, in terms of sexual expectations on dates.”

Our third research question attends to the interpersonal level of sexual scripting, where individuals make negotiations between their intrapsychic desires and the cultural expectations for appropriate behavior. The sexual double standard, relational standard, and interest in another date are context-specific and subject-specific factors that play a role in the interpersonal scripting process. We examine how attitudes about sex and gender, as well as one’s personal desires, are reflected in the sexual outcomes of a date. Specifically, which attitudes about sexual behavior are associated with the likelihood of genital contact on a date for male-initiated and female-initiated dates? (RQ 3). Hypothesis 3a states that the likelihood of genital contact on male-initiated dates will decrease when respondents hold a sexual double standard, when respondents hold a relational standard, and when respondents indicate being interested in going on another date. Historically, genital contact did not take place on dates because of the sexual double standard and women’s need to maintain respectability. Although the sexual double standard’s influence is contested, it may still inform one’s behavior on a date; therefore, if the respondent expresses holding a sexual double standard, then the likelihood of genital contact will decrease.

In addition, the relational standard may limit the extent of sexual activity on a date because dates carry the potential for romantic interest and future relationship-building. So, if respondents believe that engaging in genital contact may disqualify them as a potential boyfriend or girlfriend, then they would be less likely to engage in genital contact on a date. As such, we hypothesize that genital contact on male-initiated dates will decrease when respondents express holding a relational standard. Similarly, individuals interested in going on another date will be more likely to conform to the cultural expectation that genital contact does not take place: “[f]ew individuals wander far from the formulas of their most predictable successes” (Simon & Gagnon, 1984:58). Given a female-initiated date itself represents a deviation from a traditional script, we suspect that sexual activity will not follow the same expectations for sexual behavior. As such, we hypothesize that the likelihood of genital contact on a female-initiated date will increase when a respondents’ beliefs do not reflect a sexual double standard or a relational standard, thereby reflecting more egalitarian ideals. Similarly, hypothesis 3b states that the likelihood of genital contact on a female-initiated date will increase when respondents indicate being interested in going on another date, because there are no established guidelines that preclude sexual activity when there is romantic intent. Again, these hypotheses are exploratory given the lack of extensive research on female-initiated date processes.

Method

Data

We used data from the Online College Social Life Survey (OCSLS), which was developed by Paula England and collected between 2005 and 2011 from a convenience sample of 24,131 students across 21 institutions of higher education in the United States. The survey was optional to students 18 and older, administered in entry-level college courses, and took students about 20 min to complete. Most students who completed the survey were offered extra credit, and students who opted out of the survey were offered an alternative option for extra credit.

Students were asked to respond to questions about their experiences and attitudes regarding sexual activity, hookups, dates, and relationships. The OCSLS is the only dataset of this scale to provide this level of detailed information about college students’ dating practices, types of sexual activity, and standards for sexual behavior, all of which are needed to answer our research questions. Although our findings are not generalizable beyond those who took the survey, given the large sample size recruited from 21 institutions and the near-100 percent response rate, we believe, like other scholars, that they reflect the practices of a significant cross-section of the US student population (Allison & Risman, 2013; Kettrey, 2018; Kuperberg & Padgett, 2017).

Our analysis draws from student reports of their most recent “date,” after respondents were prompted, “Now some questions about the last date that you went on with someone you were not already in an exclusive relationship with.” Although we do not know if the respondent has been on previous dates with this person, the fact that they are not in an exclusive relationship suggests that they are still in the early stages of the courtship process. Due to our interest in gendered sexual power dynamics in courtship rituals, we limited our sample to self-identifying heterosexual, cis-gender respondents who are not married and who do not have any children. Because we are interested in the types of sexual behaviors that take place on a date, we limited our sample to those who indicated any level of sexual activity took place on their most recent date when asked, “Did anything sexual happen (kissing, petting, oral sex, intercourse all count as sexual here) happen on your date?” (N = 8,034). It is worth noting that over 60 percent of all dates involved sexual activity. After dropping cases with missing data on one or more explanatory or control variables, our total sample is comprised of 7,377 respondents.

Measures

Our dependent variable was dichotomous, measuring the extent of sexual activity on the respondent’s most recent date with someone with whom they were not in an exclusive relationship. After being asked if “anything sexual” took place on their most recent date, respondents were asked, “Which behaviors did you engage in?” and instructed to “Check all that occurred,” from a list of descriptions of various sexual behaviors (Table 1). When respondents selected at least one of the behaviors that included “genitals” in its provided definition or described “anal” or “oral” sexual activity, genital contact, which we operationalize as indicative of a nontraditional sexual outcome, was considered to have occurred on the respondent’s most recent date (1 = genital contact). The reference group, then, is traditional sexual outcomes, or no genital contact, which could be categorized as “petting.” Our decision to dichotomize this variable aligns with prior approaches that operationalize questions about sexual activity to examine specific sexual behaviors (Bearak, 2014; England & Bearak, 2014; Kettrey, 2016).

Explanatory Variables

The key explanatory variables indicated who paid for the date and who initiated more of the sexual activity. We constructed a categorical variable from responses to the question, “Who paid for the date?” We converted the responses (I paid; They paid; We both paid; There was no money spent) into gender-specific categories: man paid, woman paid or both paid, and no money was spent. We collapsed “women paid” and “both paid” into one category because women paid on less than two percent of dates. Respondents were asked, “Overall, who initiated more of the sexual activity?” We converted the responses (I did; Other person did; I don’t know) into the following categories: “Man initiated more,” “Woman initiated more,” and “I don’t know.”

We measured the relational standard based on the survey item, “If someone has hooked up a lot, I’m less interested in this person as a potential girl/boyfriend.” The 4 response options ranged from “Strongly Disagree” and “Disagree” to “Agree” and “Strongly Agree.” Following the conventions established by England and Bearak (2014), the creators of the survey, we dichotomized these items into “Disagree” (0) and “Agree” (1). Those who agreed with this statement were classified as holding a relational standard.

We measured the sexual double standard based on two survey questions where respondents were asked their opinion on the following statements: “If women hook up or have sex with lots of people, I respect them less” and “If men hook up or have sex with lots of people, I respect them less.” The statements were separated by 15 other survey items to account for bias stemming from the respondents’ conscious understanding that should not judge men and women’s sexual behaviors differently. Both of these statements were measured by 4 items: “Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Agree,” “Strongly Agree.” Because we have no reason to believe the distance between each item is equal, we dichotomized the responses into “Disagree” (0) and “Agree” (1). Respondents who agreed with the first statement (respect women less if they hook up a lot) and disagreed with the second statement (respect men less if they hook up a lot) were classified as holding gender values that align with the sexual double standard. Our construction of the relational standard and sexual double standard variables followed conventions established by other scholars who have operationalized these survey items in similar ways (Allison & Risman, 2013; England & Bearak, 2014; Kettrey, 2016).

We operationalized respondent’s interest in going on another date as an indicator of potential romantic interest based on the date. Respondents were asked, “At the end of the date, were you interested in going out on another date with this person?” and selected between the following 4 items: “No, I wasn’t at all interested”; “Possibly; I didn’t really know yet”; “Maybe; it had some appeal”; “Yes, I was definitely interested.” Because being “possibly” interested and “maybe” interested are particularly ambiguous and we have no reason to believe that the distance between each item is equal, we dichotomized these responses into “not ‘definitely interested’” (0) and “definitely interested” (1). This variable construction lends itself to a more conservative estimate.

Control Variables

Gender, race, and age were operationalized as demographic controls. Respondent gender was indicated by a dummy variable (male = 0; female = 1) derived from the question, “What is your gender?” Controlling for gender addresses potential sources of biases reported by previous research, which finds women underreport and men over report sexual behavior (England & Bearak, 2014). Measures for racial and ethnic identity were derived from the question, “If you had to pick one racial or ethnic group to describe yourself, which would it be?” where respondents selected from 14 racial categories. We recoded responses into 5 racial groups: White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Other. Age is determined from the question, “How old are you?” Respondent age ranged from 18 to 25. The average age of the sample was 20, with the majority of cases concentrated between 18 and 21 years.

We controlled for alcohol consumption and drug use before or during the date, given previous research identified the influence of alcohol on sexual activity (Kuperberg & Padgett, 2017; Morr & Mongeau, 2004; Reid et al., 2015). For alcohol consumption, respondents were asked to indicate how many beers, glasses of wine, mixed drinks or shots, and malt beverages they consumed before or during their most recent date. If respondents indicated having 1 or more of any of these beverages, alcohol was considered to be involved (1 = alcohol consumed). Respondents were asked to indicate what, if any, illegal drugs they used before or during the date by selecting all that applied from a list including marijuana, amphetamines, cocaine, ecstasy, heroin, and mushrooms. An “other” option was also provided. If respondents selected 1 or more of these options, drugs were considered to be involved (1 = drugs involved).

Because sexual history has been found to influence sexual activity (Bartoli & Clark, 2006; Olmstead et al., 2013), we controlled for respondent’s disposition toward sex using three variables: number of sexual partners, a sexual history including maintaining multiple casual sexual relationships at the same time, and a preference for having sex when in love. Respondents were asked, “How many people have you had intercourse with?” We defined 3 categories from the responses: 0 to 1 past partners; 2 to 5 past partners, and 6 or more past sexual partners. About 25 percent of respondents indicated having had intercourse with 0 to 1 people, about 50 percent of respondents indicated having had sex with 2 to 5 people, and about 25 percent of respondents indicated having had sex with 6 or more people. Respondents were asked, “Have you ever had two ongoing sexual partnerships involving intercourse at the same time?” (1 = Yes). We controlled for respondent’s association between sex and love as indicated by responses to the following statement: “I would not have sex with someone unless I was in love with them.” This statement was measured by 4 items ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” We dichotomized the responses into “Disagree” (0) and “Agree” (1), because we have no reason to believe that the distance between each option is the same.

Other versions of the model included controls for immigrant status (not born in the USA), location of high school (rural, urban, suburban), religiosity, political views, parents’ relationship status, where respondent met their date, respondent’s desire to be in a relationship, and respondent’s overall enjoyment of the date. In order to ensure statistical power, we excluded these from the final model because they carried little-to-no significance, and their presence did not notably change the coefficients of interest.

It is important to address the issue of coercion and feeling pressured to engage in certain sexual behaviors, especially given the gendered power dynamic when men initiate and pay. We could not include a variable indicating whether the respondent was pressured into sexual activity, because the variable would only apply to the subset of the sample that did engage in genital contact, rather than applying to anyone who engaged in sexual activity. With that being said, it is important to note that less than 7 percent of respondents in our sample reported feeling pressured to engage in genital contact, with 6 percent of respondents reporting performing oral sex or hand stimulation because they felt they owed their partner an orgasm but did not want to have intercourse and less than 2 percent of respondents reporting engaging in sexual intercourse because they felt verbally pressured.

Analytic Strategy

We obtained univariate descriptive statistics for the sample to assist in the operationalization of the previously described measures and examine sample distributions. To determine potential differences between male- and female-initiated dates, we use t-tests and chi-square test for independence to examine the relationship between key variables of interest and demographic controls by gender-specific date initiation. This information guided the decision to run separate models for male- and female-initiated dates to allow us to identify unique relationships between key variables and genital contact by traditionally scripted male-initiated dates and alternatively scripted female-initiated dates.

We used logistic regression to assess how much date-specific and individual-level attitudes predict genital contact occurring on a date, with separate models for male-initiated and female-initiated dates. We conducted all analyses using Stata 16 (StataCorp, 2019). First, we conducted simple logistic regressions that provided unadjusted model coefficients for each variable in the model separately. We followed these analyses with a multivariate logistic regression. The unadjusted and adjusted model coefficients from our bivariate and multivariate analyses were exponentiated, allowing us to report and compare odds ratios. This approach allows us to report and compare changes in odds ratios between the unadjusted, bivariate comparisons and the fully adjusted, multivariate logistic regression. We examined regression diagnostics and assessed for goodness of fit prior to selection of the final models (Long & Freese, 2014).

In our assessment of missing data, we determined that our data was missing at random, given there were no significant relationships between missing values and other variables. No variables had levels of missingness above 2 percent. Based on our analyses of missingness in the data, we proceeded with a complete case analysis. With complete case analysis, a total of 657 observations (~ 8.2 percent) were dropped. The final analytic sample was 7,377. The sample size of dates initiated by women (N = 805) is significantly smaller than that of dates initiated by men (N = 6,562), but we conclude that the sample still holds enough power for complete case analysis (Long & Freese, 2014).

Results

Univariate & Bivariate Analyses

Table 2 displays descriptive information about the distribution for the total sample and subsamples of male-initiated and female-initiated dates. Male initiation of dates, which aligns with the initial stage of traditional dating scripts, represents 89.1 percent of the total analytic sample while female initiation of dates, which aligns with alternative dating scripts, represents only 10.9 percent of the total analytic sample. Bivariate inferential tests demonstrated significant differences between male-initiated and female-initiated dates by genital contact. Genital contact took place on over 56 percent of dates with sexual activity, occurring on over 63 percent of female-initiated dates and on approximately 56 percent of male-initiated dates. Based on this descriptive information alone, we can see that there is a discrepancy between the widely-recited cultural expectations for sexual behavior and what is actually being reported as practiced on dates.

Although men paid for the majority of male-initiated dates (68 percent), women contributed at least part of the payment on 17 percent of dates, and no money was spent on 15 percent of dates. Among those dates following a male-initiated script, men paid and initiated most of the sexual activity on approximately 36 percent of dates. In other words, more than 60 percent of dates violate the traditional script—defined as men asking, paying, and initiating sexual activity—in some way. On female-initiated dates, which violate the script from the outset, men still paid 41 percent of the time. Women paid or both paid on 33 percent of female-initiated dates, and no money was spent on 26 percent of female-initiated dates. In addition, we observed differences by gender initiation with demographic controls, such as age (t(7375) = − 4.7, p < 0.001) and gender (\({\chi }^{2}\left(1\right)=81.7, p<0.001)\), and key explanatory variables, such as the presence of the sexual double standard (\({\chi }^{2}\left(1\right)=9.4, p<0.002)\). For age (which is not presented in Table 2), we observed an average age of 20.2 years (SD = 1.7) with an average of 20.5 years (SD = 1.8) for respondents reporting female-initiated dates and 20.2 years (SD = 1.7) for respondents reporting male-initiated dates. We did not observe differences in relational standard, interest in another date, or racial/ethnic identification between male- and female-initiated dates. Given the significant variation by this initial stage of courtship, we choose to model predictors of genital contact separately for male-initiated and female-initiated dates, which likely correspond with two different courtship scripts in contemporary America.

Table 3 displays the results of a series of simple logistic regressions that provide unadjusted odds ratios of genital contact regressed on each explanatory variable separately. This approach allowed us to compare our bivariate results directly with the odds ratios of our multivariate analyses. The unadjusted models demonstrated that variables associated with scripts and attitudes were significant within the male-initiated date sample. The bivariate analyses of the female-initiated date sample, however, demonstrated no significant association with scripts and attitudes except for when women initiated the sexual activity (compared to when men initiated sexual activity). In addition, bivariate analyses indicated significant explanatory factors were similar across both male- and female- initiated date models.

Multivariate Analyses

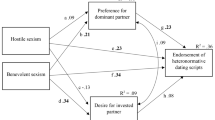

Table 4 shows the results of the multivariate logistic regression models that regress genital contact occurrence on dating scripts, attitudes/beliefs, and identified control variables. Among male-initiated dates, the odds of genital contact increased by about 31 percent when no money was spent \((p < 0.001)\) and approximately 39 percent when women paid for part or all of the date compared to when men paid \((p < 0.001)\). Holding all else equal, when women initiated more of the sexual activity on male-initiated dates, the odds of genital contact increased by approximately 39 percent compared to when men initiated more of the sexual activity \((p < 0.001)\). There was no significant difference in the odds of genital contact when the respondent indicated that they did not know who initiated more of the sexual activity compared to when men initiated. These results support Hypothesis 1, which predicted that the odds of genital contact would decrease on male-initiated dates when men paid for the date or when men initiated more of the sexual activity.

Among female-initiated dates, the odds of genital contact increased most when no money was spent, with about a 71 percent increase in odds compared to when men paid \((p < 0.01)\). The odds of genital contact when women paid or both paid on a female-initiated date increased by approximately 45 percent compared to when men paid \((p < 0.05)\). Among female-initiated dates, the effect of who initiated more of the sexual activity on the odds of genital contact was not significant. We hypothesized that the likelihood of genital contact would decrease when women paid for all or part of a female-initiated date, and that it would increase when women initiated more of the sexual activity. Hypothesis 2, then, was not supported, because women paying actually increased the odds of genital contact, and the effect of women initiating more of the sexual activity was not significant.

When respondents expressed a sexual double standard, the odds of genital contact occurring on a male-initiated date increased by about 35 percent \((p<0.001)\). When respondents indicated holding a relational standard — that is, they are less interested in someone who hooks up a lot as a future boyfriend or girlfriend—the odds of genital contact on male-initiated dates decreased by about 16 percent \((p<0.01)\). When respondents expressed interest in going on another date, the odds of genital contact occurring on a male-initiated date increased by approximately 30 percent \((p<0.001)\). Hypothesis 3a was partially supported by these estimates. As expected, holding a relational standard was a significant predictor associated with decreased odds of genital contact on a male-initiated date. Unexpectedly, however, holding a sexual double standard and being interested in another date were both significant predictors associated with increased odds of genital contact.

Among female-initiated dates, the sexual double standard and relational standard were not significant predictors of genital contact. The odds of genital contact on a female-initiated date increased by approximately 43 percent when respondents expressed interest in another date \((p<0.05)\). We predicted that the odds of genital contact would increase on female-initiated dates when respondents indicate being interested in another date and when respondents do not reflect traditional values, as indicated by holding a sexual double standard or a relational standard. Due to the lack of substantial significance, hypothesis 3b was inconclusive.

It is also important to note that we observed consistency in the significance of control variables such as gender, alcohol consumption, and sexual history across both male- and female-initiated dates. The effect of gender on genital contact was significant in both multivariate models, with the odds of reported genital contact decreasing when the respondent identified as a woman. For both male- and female-initiated dates, alcohol increased the odds of genital contact. Additionally, the effect of the number of previous sexual partners, as well as the effect of having experience maintaining multiple casual sexual arrangements at one time, increased the odds of genital contact for both male- and female-initiated dates.

Discussion

In contemporary America, hookups and dates are both acceptable pathways to relationship formation, but they are governed by different sexual scripts. The sexual behavior in hookups is ambiguously defined, and anything from kissing to intercourse is acceptable. Dates, on the other hand, are associated with more conservative sexual approaches. Scholarship has established that casual sexual interactions (i.e. hookups) can lead to dates, but we have not explored the extent of changes of sexual practices within dating contexts. Most scholarship that examines emerging adult sexual practices focuses on hookup contexts, not dates. Because traditional dating scripts are still recited and largely enacted to the extent that men initiate and pay, there are assumptions that the sexual processes that follow have not changed.

This study investigated the sexual processes of dates among college students in the US. First, we asked whether components of the traditional dating script led to traditional sexual outcomes (“petting”). Then, we asked whether components of an alternative dating script led to nontraditional sexual outcomes (genital contact). Lastly, we asked how attitudes about sexual behavior and romantic interest affected the sexual outcomes of both traditional dates (i.e., male-initiated) and nontraditional dates (i.e., female-initiated).

The Traditional Script: Male-Initiated Dates

Consistent with previous scholarship on dating scripts, sexual activity is more restricted on dates when men pay on male-initiated dates (Reid et al., 2011, 2015). This is also true when men initiate more of the sexual activity. The increase in odds associated with women initiating sexual activity is expected given the logic of the traditional cultural narrative. In the traditional script, sexual activity is limited because women are expected to limit it. It follows, then, that more sexual activity would occur if women were not only allowing sexual activity, but were also the ones initiating it.

Genital contact may be more likely to accompany nontraditional components of the script, but it is not absent in traditional ones. In other words, individuals may be following traditional components of the dating script, such as men paying, while still engaging in nontraditional sexual outcomes. This suggests a discrepancy between the cultural scenario and actual practices, which may be evidence of changing sexual scripts.

The Alternative Script: Female-Initiated Dates

Although the majority of dates in our study were male-initiated, over 88 percent of students in our sample agreed with the statement that “It is okay for women to ask men on dates.” Given this wide social acceptability, in addition to increasing egalitarian views and inclinations, the low number of female-initiated dates that we observe today reflects a lag in practice. It is likely, then, that we will see an increase of female-initiated dates in the future, and it is important for us to become attuned to their processes as distinctly different from dates that are male-initiated.

In many ways, conservative sexual practices are associated with traditionally gendered dating scripts, but there is no such association when scripts veer off the dominant cultural scenario. Female-initiated dates, which deviate from the traditional dating narrative before they even start, do not follow a recognizable sexual script, as evidenced by the general lack of significance in the model. This lack of substantial significance among female-initiated dates prompts more questions than it provides answers, but it does tell us that the processes for sexual conduct are different when traditional scripts are not followed. Ultimately, we find that predictors of genital contact on female-initiated dates are not the same as the predictors for genital contact on male-initiated dates. Future scholarship should attend to female-initiated dates and their sexual processes as part of a distinct cultural scenario. Qualitative research may be needed to assist scholars in identifying and characterizing new sexual scripts that come from female-initiated date scenarios.

The effect of who paid on the date is of particular interest, specifically the effect of no money being spent, as it is the explanatory variable with the most substantial statistical significance among female-initiated dates. When no money is spent and genital contact happens, the interaction seems to fit the description of a hookup, but the respondent specifically identified the interaction as a date. This brings up questions about what defines a date. Notably, almost 20 percent of all dates were classified as having no money spent. While it is possible that college students intentionally seek out free date activities due to their low income, they also continue to identify men paying as a defining feature of a date. This speaks to an underlying question of how a date is confirmed in this scenario, given the act of men paying on a date plays such a strong role in defining the interaction (Allison, 2019; Lamont, 2020).

When women initiate the date and no money is spent, the classification of a date is determined by different criteria. In this way, no money being spent could signal a more egalitarian date formula, given neither person in the date scenario holds financial power over the interaction. At the same time, the fact that no money being spent is the most significant predictor of genital contact on a female-initiated date suggests that some dating practices may be informed by the sexual scripts guiding hookups in ways that have yet to be uncovered.

Sexual Respectability: Double Standards and Future Dates

The sexual double standard, relational standard, and interest in going on another date speak to beliefs about what is appropriate and respectable sexual behavior. Examining the effect of standards for sexual behavior on the sexual outcomes of dates sheds light on the interpersonal scripting process that influences decisions to engage (or not engage) in sexual activity: “interpersonal scripts provide the bridge between what the parties want and what they believe is deemed to be socially appropriate and normative for a first date” (Emmers-Sommer et al., 2010:341).

On male-initiated dates, the effects of script components aligned with our expectations, but the attitudes about sexual behavior and romantic interest did not. The sexual double standard may signal a general lack of respect, which may lead to the increased odds of genital contact, assuming limiting sex is considered the “proper,” respectable thing to do. Being interested in another date increased the odds of genital contact on a male-initiated date, which is counterintuitive to the relational standard, which would dictate that sexual activity is withheld if there is interest in pursuing a relationship. While it is possible that respondents retrospectively identified being interested in another date to justify whatever sexual activity took place, we cannot be sure. The positive association between interest in another date and genital contact on a male-initiated date may also reflect how sexual boundaries and practices are being negotiated within dating contexts on the interpersonal level in ways we are not yet aware. Sex may serve as an added signal of mutual romantic interest after an interaction has been confirmed as a date and relational intent has been established, whether through verbal cues or as indicated by a man initiating and paying. It would seem, then, that despite the continued practice of certain components of the traditional dating script, with men initiating and men paying on the majority of dates, there is a discrepancy between the recitation of conservative sexual scripts and the sexual practices taking place.

Notably, neither the sexual double standard nor the relational standard had a significant effect on whether genital contact took place on a female-initiated date, suggesting that standards for appropriate sexual behavior carry less weight on female-initiated dates. This is further demonstrated by the positive relationship between genital contact on female-initiated dates and being interested in going on another date. Sexual activity may assume different meanings in the context of a female-initiated date. For instance, having sex on a female-initiated date may not be considered a violation of the relational standard because of some agreed-upon mutual interest that takes place outside of the context male-initiated, male-funded date.

Contextual Negotiations

Although women no longer depend on men to invite them out and pay for them, men still initiate the majority of dates. Scholars have suggested that the contemporary adherence to gender roles in dating scripts may be attributed to ambiguity regarding the legitimacy of a date and uncertainty regarding the other person’s intentions (Allison, 2019; Cameron & Curry, 2020). Dating most certainly has been influenced by the sexual ambiguity of hookup culture, even if conservative sexual practices are recited alongside traditional dating scripts. Current research often equates “sex” with “hookups” when looking at how sexual activity has been reordered in the courtship process. Sex may still be restricted in the scripted narrative recited by college students, but in actual practice, there seems to be more room for negotiation, especially when the date veers off script.

These negotiations start on the interpersonal level of scripting, where expectations for appropriate behavior (the cultural) confront individual desires (the intrapsychic). We can see evidence of these negotiations in our observations of how the relational standard and being interested in another date are differentially associated with nontraditional sexual outcomes. The relational standard for sexual behavior reflects the traditional expectation that sexual activity it limited in contexts where one might seek a boyfriend or girlfriend. Given the date is a context for romantic development, it makes sense that holding a relational standard would be associated with a decrease in the likelihood of genital contact. Being interested in another date reflects a desire to pursue a possible romantic relationship with someone, but unlike the relational standard, interest in another date was associated with an increase in the likelihood of genital contact. We can understand this as evidence of changing sexual norms.

Men still initiate and pay for most dates, but when the script is altered in any way, we see significant changes in the sexual processes. So, although the traditional script is still relevant, it is time to examine alternative scripts and their sexual processes. Regarding sexual practices, dates are not as homogenous as recited scripts have led us to believe, and only a minority of dates follow the traditional script completely. The dominant norm isn’t the only norm, and this study suggests that what seems to be dominant on the surface, is more diverse than we realized.

The further we get from the dating script, the more ambiguous the nature of the interaction and the more nuanced the sexual scripts become. In the case of the female-initiated dates, there is a normlessness when it comes to sexual outcomes. We see that the likelihood of genital contact increases whenever the traditional script is violated. Does veering off the script also reflect more egalitarian practices related to sex? Perhaps we are slowly moving away from these traditional dating scripts in the form of sexual negotiations. In this way, if we attend to the sexual processes of dates, we may find that the traditional dating script is not as enduring as we have come to believe.

Conclusion

This article examines whether genital contact is associated with traditional or alternative components of dating scripts. We examined variations of a dating script and their ability to predict genital contact. This study highlights the variability of sexual scripts in dating practices, suggesting that the sexual scripts associated with dates are not as homogenous or conservative as they have appeared. We cannot assume that traditional date components lead to traditional sexual activities. Scholars have grappled with the enduring relevance of traditional dating scripts despite evidence of increasingly egalitarian views (Lamont, 2014, 2020). Although we do see gendered patterns in scripted behavior when it comes to the initial logistics of the date (who asked; who paid), it seems like the sexual rules are more contextual, and there may be more room for negotiation than scholarship has previously assumed. Our findings suggest a discrepancy between what college students are saying and what they are doing.

The absence of sexual activity on dates relative to hookups has monopolized the focus of discussions about dating and the sexual processes in hookup culture. With the way hookup culture has incorporated casual sex alongside dates in the courtship process, it is important that we attend to how these changes in sexual norms may inform the sexual processes of dates. As research on traditional gender roles in courtship and the stalled gender revolution looks to dating scripts to shed light on gender inequalities, it is crucial to examine the function of sex in dating and to understand what scripts are actually being practiced and what factors may be informing them.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations that should be addressed and considered when interpreting the results. For one, as previously mentioned, the OCSLS survey data comes from a convenience sample, which means it is a nonrandom sample and therefore not generalizable. With that being said, given the large sample size with a near-perfect response rate, we believe that the data set reflects the attitudes and practices of a significant cross-section of the college student population (Allison & Risman, 2013; Kettrey, 2018; Kuperberg & Padgett, 2017). Extra credit was offered to students who took the survey, which decreases selection bias (Allison & Ralston, 2018). Students took the survey privately online, which “decrease[s] desirability bias and improve[s] the validity of responses” (Allison & Risman, 2017:480).

The respondent’s subjective assessment may also present a limitation to this study, given we do not know if the other person on the date would have defined the interaction in the same way. This is especially true of dates that veer off the traditional script. We were also limited to the respondent’s most recent date, which is not necessarily representative of their typical dating experiences.

Another limitation of this study is that we do not know if the couple has gone on a date (or hooked up) prior to the date in question. Research on dating scripts pays closest attention to first date scripts, though scholars who have examined dating scripts more generally have found similar gendered patterns (Bartoli & Clark, 2006; Lamont, 2020). Future research should consider how the number of previous dates shapes sexual outcomes. For instance, it is possible that first dates follow the cultural expectation for no genital contact, with future dates involving more sexual activity, even if the other components of the date (initiating and paying) remain traditionally gendered before exclusivity.

We also do not know how a “date” is being defined. It is generally accepted that dating “implies some level of romantic or sexual interest” (Morr & Mongeau, 2004:7). Beyond that, however, the definition of a date is taken for granted, as dates are often defined in terms of their script components. For example, women report relying on the act of men paying to signal that an interaction is a date (Allison, 2019). The variety in scripts classified as a date by respondents, however, suggests the need for a better understanding of what constitutes a date beyond the traditionally gendered signifiers. Although we do not know the respondent’s criteria for what qualifies as a date, we do know that the interaction was classified as a date with someone they were not in an exclusive relationship with.

In this study, we limited our analysis to dates where sexual activity occurred. Future research could estimate multinomial logit models to examine the effects of dating script components and attitudes on three sexual outcomes: no sexual activity, petting, and genital contact. This type of analysis may provide a more nuanced understanding of the sexual scripting process.

Future research might also consider the different operations of the sexual double standard and the relational standard. Data from the Online College Social Life Survey reported that only 16 percent of surveyed college students held a sexual double standard, in that they indicate they respect women less if they hook up with a lot of people, but not men. Over 70 percent of students held what we call a relational standard, in that they report being less interested in someone as a potential girl/boyfriend if they hook up a lot. The sexual double standard may be less articulated as college students are becoming more likely to recite egalitarian ideals. The relational standard, however, remains pervasive in its influence. In contemporary America, it seems that being chaste matters more for relationship building than reputation building. This distinction between who is considered “respectable” and who is considered “relationship material” is important for understanding the persistence of traditional gender roles in courtship despite increasing egalitarian ideals.

Our study sheds light on nuances of the dating script and sexual processes that require additional attention. These questions may become even more important as the dating landscape is shifting within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. With stay-at-home orders, mask mandates, and heightened safety precautions, dating logistics have been changing and sexual scripts are being reformulated. In the future, we may expect to see an increase in female-initiated dates, as indicated by Kendrick’s (2021) preliminary research on pandemic courtship culture, which suggests that women have been more intentional about taking an active role in dating during the pandemic. In highlighting how the sexual processes of female-initiated dates differ from male-initiated dates, our study creates an important point of departure for future research on female-initiated dates.

Availability of Data and Material

The original Online College Social Life Survey (OCSLS) was designed by Paula England and the codebook was provided by Jonathan Bearak. The data and survey instrument can be accessed at https://pages.nyu.edu/ocsls/2010/.

Code Availability

StataCorp., 2019. “Stata Statistical Software: Release 16.”

References

Allison, R. (2019). Asking out and sliding in: Gendered relationship pathways in college hookup culture. Qualitative Sociology, 42(3), 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-019-09430-2

Allison, R., & Ralston, M. (2018). Opportune romance: how college campuses shape students’ hookups, dates, and relationships. Sociological Quarterly, 59(3), 495–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2018.1479200

Allison, R., & Risman, B. J. (2013). A double standard for “hooking up”: How far have we come toward gender equality? Social Science Research, 42(5), 1191–1206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.04.006

Allison, R., & Risman, B. J. (2017). Marriage delay, time to play? Marital horizons and hooking up in college. Sociological Inquiry, 87(3), 472–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12159

Armstrong, E. A., England, P., & Fogarty, A. C. K. (2012). Accounting for women’s orgasm and sexual enjoyment in college hookups and relationships. American Sociological Review, 77(3), 435–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122412445802

Bailey, B. L. (1988). From front porch to back seat: Courtship in twentieth-century America. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bartoli, A. M., & Clark, M. D. (2006). The dating game: Similarities and differences in dating scripts among college students. Sexuality and Culture, 10(4), 54–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-006-1026-0

Bearak, J. M. (2014). Casual contraception in casual sex: life-cycle change in undergraduates’ sexual behavior in hookups. Social Forces, 93(2), 483–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou091

Cameron, J. J., & Curry, E. (2020). Gender roles and date context in hypothetical scripts for a woman and a man on a first date in the twenty-first century. Sex Roles, 82(5–6), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01056-6

Crawford, M., & Popp, D. (2003). Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 13–26.

Emmers-Sommer, T. M., Farrell, J., Gentry, A., Stevens, S., Eckstein, J., Battocletti, J., & Gardener, C. (2010). First date sexual expectations: The effects of who asked, who paid, date location, and gender. Communication Studies, 61(3), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510971003752676

England, P., & Bearak, J. (2014). The sexual double standard and gender differences in attitudes toward casual sex among U.S. university students. Demographic Research, 30(46), 1327–1338. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.46

England, P., Shafer, E. F., & Fogarty, A. C. K. (2012). Hooking up and forming romantic relationships on today’s college campuses. In M. Kimmel & A. Aronson (Eds.), The gendered society reader (5th ed., pp. 559–571). Oxford University Press.

Farvid, P., Braun, V., & Rowney, C. (2017). ‘No girl wants to be called a slut!’: Women, heterosexual casual sex and the sexual double standard. Journal of Gender Studies, 26(5), 544–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1150818

Gagnon, J. H., & Simon, W. (2005). Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality (2nd ed.). AldineTransaction.

Heldman, C., & Wade, L. (2010). Hook-up culture: Setting a new research agenda. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7(4), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-010-0024-z

Jackson, S. M., & Cram, F. (2003). Disrupting the sexual double standard: Young women’s talk about heterosexuality. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603763276153

Kendrick, S. (2021, August 6–10). Quarantined Courtship: The Cultural Implications of Dating during the Pandemic [Conference presentation]. American Sociological Association Annual Meeting, Virtual.

Kettrey, H. H. (2018). “Bad girls” say no and “good girls” say yes: sexual subjectivity and participation in undesired sex during heterosexual college hookups. Sexuality and Culture, 22(3), 685–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9498-2

Kettrey, H. H. (2016). What’s gender got to do with it? Sexual double standards and power in heterosexual college hookups. Journal of Sex Research, 53(7), 754–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1145181

Klein, V., Imhoff, R., Reininger, K. M., & Briken, P. (2019). Perceptions of sexual script deviation in women and men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1280-x

Kuperberg, A., & Padgett, J. E. (2017). Partner meeting contexts and risky behavior in college students’ other-sex and same-sex hookups. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1124378

Kuperberg, A., & Padgett, J. E. (2015). Dating and hooking up in college: Meeting contexts, sex, and variation by gender, partner’s gender, and class standing. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(5), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.901284

Kuperberg, A., & Padgett, J. E. (2016). The role of culture in explaining college students’ selection into hookups, dates, and long-term romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(8), 1070–1096. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407515616876

Lamont, E. (2020). The mating game: How gender still shapes how we date. University of California Press.

Lamont, E. (2014). Negotiating courtship: Reconciling egalitarian ideals with traditional gender norms. Gender & Society, 28(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243213503899

Laner, M. R., & Ventrone, N. A. (2000). Dating scripts revisited. Journal of Family Issues, 21(4), 488–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251300021004004

Laner, M. R., & Ventrone, N. A. (1998). Egalitarian daters/traditionalist dates. Journal of Family Issues, 19(4), 468–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251398019004005

Littauer, A. H. (2015). Bad girls: Young women, sex, and rebellion before the sixties. The University of North Carolina Press.

Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2014). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata. Stata Press.

Luff, T., Hoffman, K., & Berntson, M. (2016). Hooking up and dating are two sides of a coin. Contexts, 15(1), 76–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504216628848

Marks, M. J., & Fraley, R. C. (2005). The sexual double standard: Fact or fiction? Sex Roles, 52(3–4), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-1293-5

Masters, N. T., Casey, E., Wells, E. A., & Morrison, D. M. (2013). Sexual scripts among young heterosexually active men and women: Continuity and change. Journal of Sex Research, 50(5), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.661102

Milhausen, R. R., & Herold, E. S. (2002). Reconceptualizing the sexual double standard. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 13(2), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v13n02_05

Mongeau, P. A., & Carey, C. M. (1996). Who’s wooing whom II? An experimental investigation of date-initiation and expectancy violation. Western Journal of Communication, 60(3), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570319609374543

Mongeau, P. A., Hale, J. L., Johnson, K. L., & Hillis, J. D. (1993). Who’s wooing whom? An investigation of female initiated dating. In P. J. Kalbfleisch (Ed.), Interpersonal Communication: Evolving Interpersonal Relationships (pp. 51–68). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mongeau, P. A., & Johnson, K. L. (1995). Predicting cross-sex first-date sexual expectations and involvement: Contextual and individual difference factors. Personal Relationships, 2(4), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00094

Monto, M. A., & Carey, A. G. (2014). A new standard of sexual behavior? Are claims associated with the “Hookup Culture” supported by general social survey data? Journal of Sex Research, 51(6), 605–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.906031

Morr Serewicz, M. C., & Gale, E. (2008). First-date scripts: Gender roles, context, and relationship. Sex Roles, 58(3–4), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9283-4

Morr, M. C., & Mongeau, P. A. (2004). First-date expectations: The impact of sex of initiator, alcohol consumption, and relationship type. Communication Research, 31(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650203260202

Olmstead, S. B., Billen, R. M., Conrad, K. A., Pasley, K., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). Sex, commitment, and casual sex relationships among college men: A mixed-methods analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(4), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0047-z

Reid, J. A., Elliott, S., & Webber, G. R. (2011). Casual hookups to formal dates: Refining the boundaries of the sexual double standard. Gender & Society, 25(5), 545–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243211418642

Reid, J. A., Webber, G. R., & Elliott, S. (2015). “It’s like being in church and being on a field trip:” The date versus party situation in college students’ accounts of hooking up. Symbolic Interaction, 38(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.153

Rose, S., & Frieze, I. H. (1993). Young singles’ contemporary dating scripts. Sex Roles, 28(9–10), 499–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289677

Rose, S., & Frieze, I. H. (1989). Young singles’ scripts for a first date. Gender & Society, 3(2), 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124389003002006

Sassler, S., & Miller, A. J. (2017). Cohabitation nation: gender, class, and the remaking of relationships. University of California Press.

Sassler, S., & Miller, A. J. (2011). Waiting to be asked: Gender, power, and relationship progression among cohabiting couples. Journal of Family Issues, 32(4), 482–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10391045

Seabrook, R. C., Ward, L. M., Cortina, L. M., Giaccardi, S., & Lippman, J. R. (2017). Girl power or powerless girl? television, sexual scripts, and sexual agency in sexually active young women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(2), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316677028

Simon, W. (2005). Sexual Conduct in Retrospective Perspective. In Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality (2nd ed., pp. 290–295). AldineTransaction.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (1984). Sexual Scripts (pp. 53–60). Society.

Spurlock, J. C. (2016). Youth and sexuality in the Twentieth-Century United States. Routledge.

StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC.

Syrett, N. (2009). The Company He Keeps: A History of White College Fraternities. The University of North Carolina Press.

Thompson, A. E., Harvey, C. A., Haus, K. R., & Karst, A. (2020). An investigation of the implicit endorsement of the sexual double standard among U.S. young adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01454

Wade, L. (2017). American Hookup: the new culture of sex on campus. W. W. Norton & Company.

Weaver, A. D., Claybourn, M., & Mackeigan, K. L. (2013). Evaluations of friends-with-benefits relationship scenarios: Is there evidence of a sexual double standard? Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 22(3), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2128

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kendrick, S., Kepple, N.J. Scripting Sex in Courtship: Predicting Genital Contact in Date Outcomes. Sexuality & Culture 26, 1190–1214 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09938-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09938-2