Abstract

Precautionary measures such as physical distancing, wearing a mask, and hand hygiene to suppress virus transmission necessitated a shift in the communication paradigm.The study aimed to check the effects of wearing masks (N95, surgical, and cloth) due to the COVID-19 pandemic on interpersonal communication in audiology-speech-language pathology clinical setup from a clinician perspective. A total of 105 participants, 17 males, and 88 females, in the age range of 19 to 29 years (Mean age = 21.41 years; S.D = 1.6), participated in the study. A questionnaire consisting of 15 close-ended questions grouped into five major categories, Communication Effectiveness (3 questions), Visual Cues (5 questions), Physiological Effect (4 questions), Palliative Effect (1 question), and Environment Effect (2 questions) was framed. Procedure: Participants rated the questions using a binary forced-choice as either Yes or No adapted into a google form. Results showed that most questions in all five categories received an above-average “yes” response. A significant association between questions in communication effectiveness with visual cues and physiological effects was noticed, leading to the conclusion that wearing face masks impacted overall communication by affecting various parameters of speech, majorly, the voice. It was also seen that of all the participants, 60% used N95, 32.4% used cloth, and only 7.6% used surgical face masks. Speech-language pathologists have a significant role in facilitating oral/ verbal communication when such barriers are encountered in clients with communication disorders and fellow professionals with strategies to strengthen oral/ verbal communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was defined by World Health Organization (WHO) as an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 [1]. Precautionary measures such as physical distancing, wearing a mask, and hand hygiene to suppress virus transmission necessitated a shift in the communication paradigm. According to Cucinotta et al. (2020), the World Health Organisation considers masks as part of the comprehensive strategy of measures to control and limit the spread of the COVID-19 virus [1]. It was also advised that masks should be worn by the general public in areas where the virus is circulating, in crowded settings, where at least 1-meter of physical distancing from others is not possible, and in rooms with poor or unknown ventilation. Cheng et al. (2020) found that face masks were considered useful and less expensive, in addition to the other measures like social distancing and hand hygiene to control spreading of coronavirus disease [2].

A few studies investigated the effects of use of facemasks on oral/ verbal communication using acoustic measures. Corey et al. [3] examined the acoustic impacts of face coverings by measuring sound transmission through different types of masks, including surgical masks, masks with a transparent panel, respirators, and splash visors. The results showed that the surgical masks had the least attenuation (decreasing sound level by 2–4 dB), and transparent masks and splash visors had the most attenuation (up to 20 dB attenuation). Further, the transparent masks acted as low–pass filters, attenuating output above 2 kHz. Maryn et al. [4] compared the effect of wearing Respiratory Protection Masks (RPMs) on speech and voice sound properties and found that surgical masks had the least influence on speech characteristics while transparent plastic masks influenced the speech characteristics the most. This attenuation in terms of impact on the Speech Transmission Index (STI) was examined by Palmiero et al. [5]. The results of the study revealed that the surgical face masks had relatively less impact on STI.

Radonovich et al. [6] examined the impact of the types of masks on speech intelligibility using a standardised test and reported that the impact depended on the type of mask. Surgical masks had little or no effect on speech intelligibility, whereas half-face elastomeric respirators decreased speech intelligibility substantially. Face masks changed the speech signal, but some specific acoustic features remained largely unaffected (like the measures of voice quality) irrespective of mask type [7].

Another study compared the acoustic measures of speech when using the standard surgical mask and the KN95 mask. The findings implied that the attenuation effect on the voice spectra was less impactful while wearing the surgical mask compared to the KN95 [8]. This finding entails that a surgical mask might be a more relevant choice over the KN95 in the COVID-19 pandemic to minimise the impact on communication. A similar study illustrated the effects of N95 masks and face shields on speech perception among healthcare workers in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic scenario and showed that speech perception was significantly affected when personal protective equipment was used while communicating [9]. It was found that face coverings have impacted communication, especially in people with hearing loss. These findings illustrate the need to be aware of the communication-friendly face coverings and emphasise the need to be communication-aware when wearing a face covering [10].

On a pragmatic-social aspect, a study illustrated the real-world impact on emotion perception from covering the mouth region. Results indicated that although satisfaction with a medical appointment was unaffected when the physician wore face-covering such as the face masks, but the physician was viewed as being less empathic [11]. Also, the mouth and nose cover limited access to speech reading cues along with alteration in acoustics. Although the benefit gained was highly variable across individuals, the speech reading cues were perceived to be essential as it supplemented the incoming speech information in spite of the benefit gained was highly variable [12, 13].

Other studies on the effect of face masks on communication during the COVID-19 pandemic also showed that initiating coping strategies and skills for communication when using face masks is important to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and any other pandemic in the future [14, 15]. A study that explored the impact of mask-wearing on communication in healthcare showed that the ability of the healthcare workers to effectively communicate with patients and other workers was compromised [13]. It was also shown that the efficiency, effectiveness, equitability, and therapeutic rehabilitation safety were reported to be adversely affected.

An Indian study investigated the problems of face-to-face communication while wearing a face mask. The result revealed that the lower portions of the face were important for facial expression communication and that the use of facial expressions to complement communication has been phased out since the compulsive use of face masks [16]. Another study done in the Chennai region of India investigated the difficulties patients face during communication with their healthcare professionals. More than 60% of the participants reported facing barriers in communication due to several factors, among which mandatory use of facial masks was a major factor [17].

Although wearing a facial mask is considered an effective source of controlling the spread of infection, meeting communication success, has substantially reduced for numerous mask wearers. Altered acoustic characteristics of speech, absence of lip reading cues, limited facial expressions are all challenges that have emerged post wearing a facemask while communicating. Effective communication between the healthcare workers and the patients is essential in order to deliver healthcare services effectively. Verbal communication plays a significant role in the field of rehabilitation sciences. General change in the communication pattern impacted the functioning of regular clinics and use of the standard clinical protocols. The most impacted individuals were training to be professionals in the field of audiology and speech-language pathology. In this context, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of wearing face masks due to the COVID-19 pandemic on interpersonal communication in audiology & speech-language pathology clinical setup from the clinician perspective and their preferred type (N95, surgical, and cloth) of the face masks.

Method

The study was conducted as an online survey using a convenient sampling method, with questions designed to cover a wide range of problems that could be postulated as occurring in listening situations and social interactions between the healthcare workers and the patients in a clinical setup.

Participants

A total of 190 individuals in the final year of the undergraduate program and postgraduate programs of Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology courses of an institution were invited to participate in the study. Among them, only 110 individuals responded and formed the participants of the study. Reminder emails were sent, and completion of data collection spanned over a duration of one month. The participants who volunteered to participate in the study were further screened based on the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria set were: (a) placed in the regular clinical postings during which use of face masks was mandatory, (b) prior experience of providing clinical services without masks (pre-pandemic), and (c) prior experience of regular one-on-one interactions with the clients and (d) no history of infections of the ear, nose, and throat during the time of data collection. After applying the inclusion criteria, a total of 105 participants, 17 males, and 88 females, in the age range of 19 to 29 years (Mean age = 21.41 years; S. D = 1.6) participated in the study. The study conformed to the institutional and ethical guidelines for Biobehavioral Research involving human subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to their enrolment in the study.

Material

A 25-item questionnaire was framed to check the effects of wearing face masks on interpersonal communication in a clinical setup from a clinicians’ perspective. The questionnaire was validated by qualified and experienced three Speech-Language Pathologists, three Audiologists, and three Clinical Psychologists. The content validation was carried out on the parameters of appropriateness of questions on a 5-point rating scale. Ambiguous questions, which received ratings less than two (< 2), were removed from the list. The final content validated questionnaire consisted of 15 close-ended questions except for question no. 12, which required an explanation for the Yes/No choices selected (See Appendix). The 15 questions were further grouped into five major categories that were Communication Effectiveness (questions 1, 2, & 10), Visual Cues (questions 3, 4, 5, 8, & 9), Physiological Effect (questions 6, 7, 11, & 13), Palliative Effect (question 12) and Environment Effect (questions 14 & 15). The participants rated these questions using a binary forced-choice response rating scale as either Yes or No.

Procedure

The questionnaire was adapted into a google form consisting of all the 15 closed-set questions. Questions on demographic details and the consent statement were also added to the initial part of the google form and were made mandatory. These forms were emailed individually to the personal mail id by the authors. Participants were requested to choose either a Yes or No response to each of the 15 questions and elaborate on an answer for question no. 12.

Analysis

The responses of all the participants were averaged question-wise and tabulated for statistical analysis. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (Version 20) was used to analyse the data. The binary responses to the questions were summarised by generating crosstabs of the descriptive statistical measures, such as the mean percentage of responses. Additionally, a Chi-square test of association was done to understand any significant relationship between the responses to the questions from the categories of Communication Effectiveness, Visual Cues, Physiological Effects, and Environmental Effects.

Results

One hundred and five participants participated in the questionnaire survey, the vast majority of whom were females (n = 88). The results were scrutinised to understand the impact of facial masks through the questions in the five major categories. It was noted that most questions in all the five categories received a maximum affirmative “yes” response. When asked about the role of Speech-Language Pathologists (SLP) in supporting the communication in the context of mask-wearing, 50.5% opined that SLPs have a role. The respondents suggested SLPs could take up roles in educating the public about talking slowly with appropriate use of suprasegmentals and loudness levels and voice care while using face masks. The data obtained was analysed using descriptive statistical methods. Cross tabs of the responses obtained for each question were formulated. The mean percentage scores are given in Table 1 and figuratively represented in Fig. 1.

The Chi-square test of association was done to analyse the association between the responses to the questions in the category of communication effectiveness with Visual cues, PhysiologicaleEffect, and Environmental Effect (Table 2).

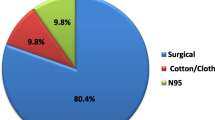

When the choices of the types of face masks used were analysed, of the 105 participants, only 7.6% were found to use surgical, 60% used N95, and 32.4% used cloth face masks. Further, a majority of the participants wore N95 (76.2% females and 23.8% males), followed by cloth face masks (45.7% females and 14.3% males), and only 7.6% females used surgical facemasks. None of the male participants used surgical face masks.

Discussion

Analysis of the responses of all the questions revealed that the maximum number of questions in all categories received an above-average “yes” response from most participants. This indicated that the sudden change in the existing communication situation, confounded by unfamiliar and prevalent challenges made wearing face masks essential for safeguarding oneself and others, leading to the high affirmative responses. Further, it was noted that for question 13, the physiological category had the least score (50.5%) for “yes” response. The participants were alienated in their responses, wherein 50.5% of participants indicated that they were “unable to hear communication of the clients”, and the remaining 49.5% of participants reported that they heard the speech of clients with face masks clearly. The response of majority (50.5%) pointing out the difficulty in hearing the clients finds support in the results of Bandaru et al. (2020), who reported a significant decrease in the speech reception and speech discrimination scores in their participants (twenty health care workers with normal hearing) while using personal protective equipment (N95 mask and face shield) [9]. However, the speech reception and discrimination abilities may need closer scrutiny using quantitative auditory assessment. Seventy-one point four percent of the participants indicated “yes” to the use of technology and other aids to facilitate their communication, and this is in consonance with the findings of Mheidly (2020), who advocated the use of telecommunication for interpersonal interactions to facilitate communication while wearing a face mask [15].

When association effects across the major categories were checked, the Chi-square test showed a statistically significant association with responses of questions in Communication Effectiveness with the responses to the questions in Visual Cue and Physiological effect groups but not with Environment Effect. This leads to the inference that the communication effectiveness was not significantly influenced by environmental issues, such as the physical background, infrastructure of the setup, etc., or even the use of other aids to facilitate communication. The influence of Visual Cues and Physiological Effects was significant, suggesting effective communication was hindered by the lack of sufficient visual cues from the speaker and leading to over-reliance on body language, gestures, and suprasegmental features. Similar findings that led to communication stress were reported by Luo et al. [18] and Mheidly et al. [15]. The probability of the “McGurk effect,“ wherein the misinterpretation of stimuli occurs when there is a dissonance between the visual and auditory stimuli during the use of facial masks, was also emphasised by Campagne [14]. Likewise, the speakers experiencing breathing discomforts and use of strenuous voice to be heard through the facial masks and strained listening leading to prolonged communication interaction time (physiological effects) was found to significantly affect the communication effectiveness, which found support from the results of Esmaeilzadeh et al. [19]. He reported physiological discomfort like headache, acne, increased facial temperature, etc., as the strongest variables affecting the attitude towards mask-wearing. These factors further led to communication failures, disturbing the patient-clinician relational continuity [4].

The majority of the participants in this study preferred N95 masks, followed by cloth masks, and the preference for surgical masks was the least. Preference for the type of the mask may be primarily to safeguard one’s health or a personal choice of the individual for ease of communication and or easy accessibility and warrants further investigation.

Overall, the results of the current study showed that the use of face masks in the clinical setup affected interpersonal communication. A report from India on the different non-verbal communication strategies that could be used to establish patient-doctor rapport listed the following: Eye contact, Paralinguistics, Body gestures and movements, and being a patient-listener [20]. The need for alternative communication strategies is becoming essential, just like for any other healthcare worker, for effective healthcare delivery, as also suggested by Bandaru et al. [9]. Further, this overall effect of breakdown in communication could hinder a better service delivery, which may also have a bearing on both patient and clinician well-being and could have a significant economic impact on healthcare systems globally [13].

Conclusion

Wearing face masks impacts overall communication, affects breathing, strains the voice of the talkers, and causes hesitation to converse as the listeners stare at the talkers paying close attention to the upper parts of their faces to comprehend the messages, in turn, prolonging the communication interactions and/ or communication breakdown. This necessitates the Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists to facilitate communication to strengthen communication means of clients with communication disorders and fellow professionals. Using alternate communication strategies when using personal protective devices, such as face masks and face shields, should be advocated and encouraged as facilitators for effective communication.

References

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M (2020) WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm 91(1):157

Cheng VCC, Wong SC, Chuang VWM, So SYC, Chen JHK, Sridhar S et al (2020) The role of community-wide wearing of face mask for control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect 81(1):107–114

Corey RM, Jones U, Singer AC (2020) Acoustic effects of medical, cloth, and transparent face masks on speech signals. J Acoust Soc Am 148(4):2371–2375

Maryn Y, Wuyts FL, Zarowski A (2021) Are acoustic markers of voice and speech signals affected by nose-and-mouth-covering respiratory protective masks? J Voice (In press)

Palmiero AJ, Symons D, Morgan JW III, Shaffer RE (2016) Speech intelligibility assessment of protective facemasks and air-purifying respirators. J Occup Environ Hyg 13(12):960–968

Radonovich LJ Jr, Yanke R, Cheng J, Bender B (2009) Diminished speech intelligibility associated with certain types of respirators worn by healthcare workers. J Occup Environ Hyg 7(1):63–70

Magee M, Lewis C, Noffs G, Reece H, Chan JC, Zaga CJ et al (2020) Effects of face masks on acoustic analysis and speech perception: implications for peri-pandemic protocols. J Acoust Soc Am 148(6):3562–3568

Nguyen DD, McCabe P, Thomas D, Purcell A, Doble M, Novakovic D et al (2021) Acoustic voice characteristics with and without wearing a facemask. Sci Rep 11(1):1–11

Bandaru SV, Augustine AM, Lepcha A, Sebastian S, Gowri M, Philip A et al (2020) The effects of N95 mask and face shield on speech perception among healthcare workers in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic scenario. J Laryngol Otol 134(10):895–898

Saunders GH, Jackson IR, Visram AS (2021) Impacts of face coverings on communication: an indirect impact of COVID-19. Int J Audiol 60(7):495–506

Wong CKM, Yip BHK, Mercer S, Griffiths S, Kung K, Wong MCS et al (2013) Effect of facemasks on empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 14(1):1–7

MacLeod A, Summerfield Q (1990) A procedure for measuring auditory and audiovisual speech-reception thresholds for sentences in noise: Rationale, evaluation, and recommendations for use. Br J Audiol 24(1):29–43

Marler H, Ditton A (2021) “I’m smiling back at you”: exploring the impact of mask wearing on communication in healthcare. Int J Lang Commun Disord 56(1):205–214

Campagne DM (2021) The problem with communication stress from face masks. J Affect Disord Reports 3:100069

Mheidly N, Fares MY, Zalzale H, Fares J (2020) Effect of face masks on interpersonal communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Heal 8:582191

Prusti SM, Dash M (2022) Effect of the mask on communication: a perspective of the scenario of covid-19. Asian J Res Soc Sci Humanit 12(1):188–201

Gopichandran V, Sakthivel K (2021) Doctor-patient communication and trust in doctors during COVID 19 times—A cross sectional study in Chennai, India. PLoS ONE 16(6):e0253497

Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H (2020) The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 291:113190

Esmaeilzadeh P (2022) Public concerns and burdens associated with face mask-wearing: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Prog Disaster Sci 13:100215

Kaul P, Choudhary D, Garg PK (2021) Deciphering the Optimum Doctor-Patient Communication Strategy during COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Surg Oncol 12:240–241

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all the participants, Director, All India Institute of Speech and Hearing – Mysuru and Mr. R. Srinivasa, Biostatistician-AIISH, Mysuru.

Funding

This particular study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author 1: Conception and design of the work; revising it critically for important intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published. Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Authors 2: Data acquisition, data analysis, drafting the work Author 3: Data analysis, interpretation of data and drafting the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study conformed to the Ethical Guidelines for BioBehavioral Research Involving Human Subjects by the AIISH ETHICS COMMITTEE (AEC).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Questionnaire

Name: | Age | Sex |

Education | ||

Class | ||

Instruction: Indicate your choice by choosing "Yes" if you agree with the question or "No" if you disagree with the question. | ||

Sl. No. | Questions | Categories |

|---|---|---|

1. | Do you feel that the clients find it difficult to follow the instructions of clinicians wearing masks? | Communication effectiveness |

2. | Do you feel wearing a mask is a barrier to effective communication as it hinders clear communication and needs multiple repetitions/ clarifications? | Communication effectiveness |

3. | Do you feel prolonged eye contact necessary to maintain the conversation while wearing mask seems uncomfortable to some people? | Visual cues |

4. | Do you feel that communication breakdowns and communication errors (misunderstanding of instructions) are more frequent since subtle facial cues are lost? | Visual cues |

5. | Do you find it challenging and time consuming to find innovative ways for rapport building to provide effective assessment and therapy/ intervention to your clients while wearing a mask? | Visual cues |

6. | Do you experience breathing difficulty/ shortness of breath/panting while wearing masks and communicating? | Physiological effect |

7. | Do you feel your voice is strained/ distorted/ muffled while wearing the mask and talking? | Physiological effect |

8. | Do you feel that the mask hides your facial expressions? | Visual cues |

9. | Do you pay more attention to the talkers’ eyebrows, eye contact, the overall body language and gestures? | Visual cues |

10. | Do you pay more attention to the suprasegmentals of speaker’s voice? | Communication effectiveness |

11. | Do you use masks for a prolonged duration of time (6-8 h/day)? | Physiological effect |

12. | Do the SLPs have a role in supporting communication in context of mask wearing? Explain in 5–6 words. | Palliative Effect |

13. | Do you feel you can hear clearly while communicating with the clients wearing masks? | Physiological effect |

14. | Do you feel that the physical background, infrastructure and work environment affect the mask wearing? | Environmental effect |

15. | Do you use technology and other aids (writing on paper, using signs or gestures, pointing) to facilitate communication? | Environmental effect |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yeshoda, K., Siya, S., Chaithanyanayaka, M. et al. Impact of Facemasks Use on Interpersonal Communication in a Clinical Setup: A Questionnaire Based Study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 75, 765–771 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-022-03465-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-022-03465-8