Abstract

Purpose of Review

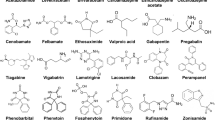

This review summarizes the current FDA practice in developing risk- and evidence-based product-specific bioequivalence guidances for antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).

Recent Findings

FDA’s product-specific guidance (PSG) for AEDs takes into account the therapeutic index of each AED product. Several PSGs for AEDs recommend fully replicated studies and a reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RS-ABE) approach that permit the simultaneous equivalence comparison of the mean and within-subject variability of the test and reference products.

Summary

The PSGs for AEDs published by FDA reflect the agency’s current thinking on the bioequivalence studies and approval standards for generics of AEDs. Bioequivalence between brand and generic AED products demonstrated in controlled studies with epilepsy patients provides strong scientific support for the soundness of FDA bioequivalence standards.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia. 2005;46(4):470–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Public Health Dimensions of the Epilepsies. Epilepsy across the Spectrum: promoting health and understanding. Washington (DC): National Academic Press (US); 2012.

Epilepsy, One of the Nation’s Most Common Neurological Conditions at a Glance 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/AAG/epilepsy.htm.

Practice Guidelines for Epilepsy. https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/Home/ByTopic?topicId=23.

Brodie MJ, Barry SJ, Bamagous GA, Norrie JD, Kwan P. Patterns of treatment response in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Neurology. 2012;78(20):1548–54. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182563b19.

•• Orange Book: approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence evaluations. 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/default.cfm. The Orange Book identifies brand and generic drug products approved on the basis of safety and effectiveness by the FDA.

Paschal AM, Rush SE, Sadler T. Factors associated with medication adherence in patients with epilepsy and recommendations for improvement. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;31:346–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.10.002.

Title 21, Code of Federal Regulations, Section 314.3. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=314.3.

Draft guidance for industry: bioequivalence studies with pharmacokinetic endpoints for drugs submitted under an Abbreviated New Drug Application. 2013. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM377465.pdf.

Guidance for industry: statistical approaches to establishing bioequivalence. 2001. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm070244.pdf.

FDA policy on generic anticonvulsants. SCRIP. 1989;1469:28–9.

• LX Y, Jiang W, Zhang X, Lionberger R, Makhlouf F, Schuirmann DJ, et al. Novel bioequivalence approach for narrow therapeutic index drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97(3):286–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.28. Summary of FDA-proposed bioequivalence study design and related data analysis for NTI drugs.

Davit BM, Nwakama PE, Buehler GJ, Conner DP, Haidar SH, Patel DT, et al. Comparing generic and innovator drugs: a review of 12 years of bioequivalence data from the United States Food and Drug Administration. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(10):1583–97. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1M141.

Product-specific guidances for generic drug development. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm075207.htm.

Yasiry Z, Shorvon SD. How phenobarbital revolutionized epilepsy therapy: the story of phenobarbital therapy in epilepsy in the last 100 years. Epilepsia. 2012;53(Suppl 8):26–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12026.

Product label of phenytoin chewable tablets. 2015. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/084427Orig1s032lbl.pdf.

Product label of phenytoin oral suspension. 2016. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/008762s057s058lbl.pdf.

Product label of carbamazepine extended-release tablets. 2015. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/016608s097,018281s045,018927s038,020234s026lbl.pdf. Accessed Aug 2015.

Specht U, May TW, Rohde M, Wagner V, Schmidt RC, Schutz M, et al. Cerebellar atrophy decreases the threshold of carbamazepine toxicity in patients with chronic focal epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(4):427–31.

Spiller HA, Krenzelok EP, Cookson E. Carbamazepine overdose: a prospective study of serum levels and toxicity. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1990;28(4):445–58.

Product label of valproic acid capsules. Mar 2017. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/018081s066,018082s049lbl.pdf.

• Jiang W, Makhlouf F, Schuirmann DJ, Zhang X, Zheng N, Conner D, et al. A bioequivalence approach for generic narrow therapeutic index drugs: evaluation of the reference-scaled approach and variability comparison criterion. AAPS J. 2015;17(4):891–901. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-015-9753-5. Evaluation of different bioequivalence approaches for NTI drugs using modeling and simulation.

Draft guidance on warfarin sodium oral tablets. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM201283.pdf.

French JA, Gazzola DM. New generation antiepileptic drugs: what do they offer in terms of improved tolerability and safety? Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2(4):141–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098611411127.

Privitera M, Welty T, Gidal B, Carlson C, Pollard J, Berg M. How do clinicians adjust lamotrigine doses and use lamotrigine blood levels?—a Q-PULSE survey. Epilepsy Curr. 2014;14(4):218–23. https://doi.org/10.5698/1535-7597-14.4.218.

Cai W, Ting T, Polli J, Berg M, Privitera M, Jiang W. Lamotrigine, a narrow therapeutic index drug or not? Am Acad Neurol Ann Meet Philadelphia Abstract. 2014;P4:267.

Draft guidance for industry: waiver of in vivo bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for immediate-release solid oral dosage forms based on a biopharmaceutics classification system. 2015. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm070246.pdf.

Product label of felbamate tablets and oral suspension. Jul 2011. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/020189s023lbl.pdf.

Product label of vigabatrin tablet and oral solution. Jun 2016. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/020427Orig1s014,022006Orig1s015bl.pdf.

• Gauthier AC, Mattson RH. Clobazam: a safe, efficacious, and newly rediscovered therapeutic for epilepsy. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2015;21(7):543–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.12399. A review of clobazam safety and efficacy.

Product label of eslicarbazepine acetate oral tablets. 2015. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/022416s001lbl.pdf.

Rogawski MA. Brivaracetam: a rational drug discovery success story. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(8):1555–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjp.2008.221.

Product label of perampanel oral tablets and oral suspension. 2016. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/208277s000lbl.pdf.

Werz MA. Pharmacotherapeutics of epilepsy: use of lamotrigine and expectations for lamotrigine extended release. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(5):1035–46.

LeLorier J, Duh MS, Paradis PE, Lefebvre P, Weiner J, Manjunath R, et al. Clinical consequences of generic substitution of lamotrigine for patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 2008;70(22 Pt 2):2179–86. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000313154.55518.25.

Andermann F, Duh MS, Gosselin A, Paradis PE. Compulsory generic switching of antiepileptic drugs: high switchback rates to branded compounds compared with other drug classes. Epilepsia. 2007;48(3):464–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01007.x.

•• Ting TY, Jiang W, Lionberger R, Wong J, Jones JW, Kane MA, et al. Generic lamotrigine versus brand-name Lamictal bioequivalence in patients with epilepsy: a field test of the FDA bioequivalence standard. Epilepsia. 2015;56(9):1415–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13095. Bioequivalence testing of generic lamotrigine and Lamictal in patients who are potentially sensitive to problems with generic switching.

•• Privitera MD, Welty TE, Gidal BE, Diaz FJ, Krebill R, Szaflarski JP, et al. Generic-to-generic lamotrigine switches in people with epilepsy: the randomised controlled EQUIGEN trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):365–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00014-4. Bioequivalence testing of two disparate generic lamotrigine products in patients with epilepsy.

Berg M, Privitera M, Diaz F, Dworetzky B, Elder E, Gidal B, et al. Equivalence among generic AEDs (EQUIGEN): single-dose study. Am Epilepsy Soc Ann Meet Philadelphia Abstract. 2015;2:267.

•• Vossler DG, Anderson GD, Bainbridge JAES. Position statement on generic substitution of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16(3):209–11. https://doi.org/10.5698/1535-7511-16.3.209. AES acknowledges that drug formulation substitution with FDA-approved generic products reduces cost without compromising efficacy.

• Kesselheim AS, Bykov K, Gagne JJ, Wang SV, Choudhry NK. Switching generic antiepileptic drug manufacturer not linked to seizures: a case-crossover study. Neurology. 2016;87(17):1796–801. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003259. Estimation the risk of seizure-related events associated with switching generic AED manufacturers.

• Johnson EL, Chang YT, Davit B, Gidal BE, Krauss GL. Assessing bioequivalence of generic modified-release antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2016;86(17):1597–604. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002607. A review of bioequivalence studies of approved generic modified-release AEDs.

• Krauss GL. Potential influence of FDA-sponsored studies of antiepilepsy drugs on generic and brand-name formulation prescribing. JAMA Neurol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0492. A summary of clinical impact of FDA-sponsored lamotrigine bioequivalence studies and clinicians’ concerns remaining to be addressed.

Jiang W. Therapeutic equivalence of generic modified release AED products. American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting; Houston; 2016.

Tothfalusi L, Endrenyi L. Approvable generic carbamazepine formulations may not be bioequivalent in target patient populations. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51(6):525–8. https://doi.org/10.5414/CP201845.

Fang L. Bioequivalence study designs for anti-epileptic drugs (AED). American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting; Houston; 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Zhichuan Li, Lanyan Fang, Wenlei Jiang, Myong-Jin Kim, and Liang Zhao declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Epilepsy

This article reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views or policies of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Fang, L., Jiang, W. et al. Risk-Based Bioequivalence Recommendations for Antiepileptic Drugs. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 17, 82 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0795-1

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0795-1