Abstract

Brain calcifications may be an incidental finding on neuroimaging in normal, particularly older individuals, but can also indicate numerous hereditary and nonhereditary syndromes, and metabolic, environmental, infectious, autoimmune, mitochondrial, traumatic, or toxic disorders. Bilateral calcifications most commonly affecting the basal ganglia may often be found in idiopathic cases, and a new term, primary familial brain calcification (PFBC), has been proposed that recognizes the genetic causes of the disorder and that calcifications occurred well beyond the basal ganglia. PFBC, usually inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, is both an intrafamilial and an interfamilial heterogeneous disorder, clinically characterized by an insidious and progressive development of movement disorders, cognitive decline, and psychiatric symptoms, but also cerebellar ataxia, pyramidal signs, and sometimes isolated seizures and headaches/migraines. Heterozygous mutations in four genes (SLC20A2, PDGFRB, PDGFB, XPR1) have recently proved to be the causes of the autosomal dominant forms of PFBC, also suggesting disrupted phosphate homeostasis as “an underlying and converging” pathophysiological mechanism. However, to date, it is not possible to anticipate with acceptable certainty any of known genetic causes of PFBC on the basis of the type, severity, pattern of distribution, or combination of movement disorders (mainly parkinsonism, with or without tremor, but also dystonia, chorea, paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia, orofacial dyskinesia, and gait and speech disorders).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Forstl H, Krumm B, Eden S, Kohlmeyer K. Neurological disorders in 166 patients with basal ganglia calcification: a statistical evaluation. J Neurol. 1992;239:36–8.

Simoni M, Pantoni L, Pracucci G, Palmertz B, Guo X, Gustafson D. Prevalence of CT-detected cerebral abnormalities in an elderly Swedish population sample. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:260–7.

Yamada M, Asano T, Okamoto K, et al. High frequency of calcification in basal ganglia on brain computed tomography images in Japanese older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:706–10.

Donaldson I, Marsden CD, Schneider S, Bhatia K. Basal ganglia calcification. In: Marsden's book of movement disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 585–93.

Keller A, Westenberger A, Sobrido MJ, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding PDGF-B cause brain calcifications in humans and mice. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1077–82.

Baba Y, Broderick DF, Uitti RJ, et al. Heredofamilial brain calcinosis syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:641–51.

Sobrido MJ, Coppola G, Oliveira J et al. Primary familial brain calcification. In: GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 2004. p. 1993–2014.

Nicolas G, Pottier C, Charbonnier C, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of probable and genetically-confirmed idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Brain. 2013;136:3395–407.

Manyam BV. What is and what is not ‘Fahr’s disease’. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11:73–80.

Saleem S, Aslam HM, Anwar M, et al. Fahr's syndrome: literature review of current evidence. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:156.

• Deng H, Zheng W, Jankovic J. Genetics and molecular biology of brain calcification. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;22:20–38. This publication is important since it provides a comprehensive review of major aspects of genetics and molecular biology of brain calcification.

Lowenthal A, Bruyn G. Calcification of the striopallidodentate system. Handb Clin Neurol. 1968;6:703–25.

Goswami R, Sharma R, Sreenivas V, et al. Prevalence and progression of basal ganglia calcification and its pathogenic mechanism in patients with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77:200–6.

Mancini F, Zangaglia R, Cristina S, et al. Secondary cervical dystonia in iatrogenic hypoparathyroidism associated with extensive brain calcifications. Funct Neurol. 2006;21:165–6.

Kowdley KV, Coull BM, Orwoll ES. Cognitive impairment and intracranial calcification in chronic hypoparathyroidism. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317:273–7.

Kim TW, Park IS, Kim SH, et al. Striopallidodentate calcification and progressive supranuclear palsy-like phenotype in a patient with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Neurol. 2007;3(1):57–61.

Galvez-Jimenez N, Hanson MR, Cabral J. Dopa-resistant parkinsonism, oculomotor disturbances, chorea, mirror movements, dyspraxia, and dementia: the expanding clinical spectrum of hypoparathyroidism. a case report. Mov Disord. 2000;15:1273–6.

Kis B, Hedrich K, Kann M, et al. Oculogyric dystonic states in early-onset parkinsonism with basal ganglia calcifications. Neurology. 2005;65:761.

Agarwal R, Lahiri D, Biswas A, et al. A rare cause of seizures, parkinsonian, and cerebellar signs: brain calcinosis secondary to thyroidectomy. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:540–2.

Barabas G, Tucker SM. Idiopathic hypoparathyroidism and paroxysmal dystonic choreoathetosis. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:585.

Kwon YJ, Jung JM, Choi JY, Kwon DY. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia in pseudohypoparathyroidism: is basal ganglia calcification a necessary finding? J Neurol Sci. 2015;357:302–3.

Margolin D, Hammerstad J, Orwoll E, et al. Intracranial calcification in hyperparathyroidism associated with gait apraxia and parkinsonism. Neurology. 1980;30:1005–7.

Montilla-Uzcátegui V, Araujo-Unda H, Daza-Restrepo A, et al. Paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesias responsive to carbamazepine in Fahr syndrome: a case report. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39:262–4.

Bassett AS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Devriendt K, et al. Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. J Pediatr. 2011;159:332–9.

Boot E, Butcher NJ, van Amelsvoort TA, et al. Movement disorders and other motor abnormalities in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167:639–45.

Fung WL, Butcher NJ, Costain G, et al. Practical guidelines for managing adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Genet Med. 2015;17:599–609.

Pasick C, McDonald-McGinn DM, Simbolon C, et al. Asymmetric crying facies in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Implications for future screening. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52:1144–8.

Schneider M, Debbané M, Bassett AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders from childhood to adulthood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: results from the international consortium on brain and behavior in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:627–39.

Butcher N, Kiehl T, Hazrati L, et al. Individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome are at increased risk of early-onset Parkinson disease: identification of a novel genetic form of Parkinson disease and its clinical implications. JAMA Neurol. 2013:1359–66.

Hammans SR, Sweeney MG, Hanna MG, et al. The mitochondrial DNA transfer RNALeu(UUR) A!G(3243) mutation. a clinical and genetic study. Brain. 1995;118:721–34.

Nakagaki H, Furuya J, Santa Y, et al. A case of MELAS presenting juvenile-onset hyperglycemic chorea-ballism. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2005;45:502–5.

Singmaneesakulchai S, Limotai N, Jagota P, Bhidayasiri R. Expanding spectrum of abnormal movements in MELAS syndrome (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes). Mov Disord. 2012;27:1495–7.

Sidiropoulos C, Moro E, Lang AE. Extensive intracranial calcifications in a patient with a novel polymerase γ-1 mutation. Neurology. 2013;81:197–8.

Habuchi C, Iritani S, Sekiguchi H, et al. Clinicopathological study of diffuse neurofibrillary tangles with calcification. with special reference to TDP-43 proteinopathy and alpha-synucleinopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301:77–85.

Tsuchiya K, Nakayama H, Haga C, et al. Distribution of cerebral cortical lesions in diffuse neurofibrillay tangles with calcification: a clinicopathological study of four autopsy cases showing prominent parietal lobe involvement. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:57–68.

Faissner S, Hoepner R, Ellrichmann G, et al. Atypical occipital calcinosis in a Caucasian individual with probable diffuse neurofibrillary tangles with calcification. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2022–4.

Labrune P, Lacroix C, Goutières F, et al. Extensive brain calcifications, leukodystrophy, and formation of parenchymal cysts: a new progressive disorder due to diffuse cerebral microangiopathy. Neurology. 1996;46:1297–301.

Stephani C, Pfeifenbring S, Mohr A, Stadelmann C. Late-onset leukoencephalopathy with cerebral calcifications and cysts: case report and review of the literature. BMC Neurol. 2016;6:16–9.

Karlinger K, Tárnoki ÁD, Tárnoki DL, et al. Leukoencephalopathy, cerebral calcifications and cysts: a family study. J Neurol. 2014;261:1911–6.

Wang C, Li Y, Shi L, et al. Mutations in SLC20A2 link familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification with phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:254–6.

Manyam BV, Walters AS, Narla KR. Bilateral striopallidodentate calcinosis: clinical characteristics of patients seen in a registry. Mov Disord. 2001;16:258–64.

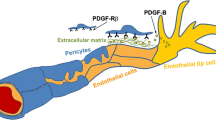

Betsholtz C, Keller A. PDGF, pericytes and the pathogenesis of idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (IBGC). Brain Pathol. 2014;24:387–95.

• Westenberger A, Klein C. The genetics of primary familial brain calcifications. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14:490. This publication is important since it provides a comprehensive review of major aspects of the genetics of PFBC.

• Taglia I, Mignarri A, Olgiati S, et al. Primary familial brain calcification: genetic analysis and clinical spectrum. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1691–5. This publication is important since it provides a comprehensive review of major aspects of the genetics and clinical aspects of PFBC.

• Taglia I, Bonifati V, Mignarri A, et al. Primary familial brain calcification: update on molecular genetics. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:787–94. This publication is important since it provides a comprehensive review of major aspects of the genetics of PFBC.

da Silva RJ, Pereira IC, Oliveira JR. Analysis of gene expression pattern and neuroanatomical correlates for SLC20A2 (PiT-2) shows a molecular network with potential impact in idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (“Fahrʼs disease”). J Mol Neurosci. 2013;50:280–3.

Inden M, Iriyama M, Takagi M, et al. Localization of type-III sodium-dependent phosphate transporter 2 in the mouse brain. Brain Res. 2013;1531:75–83.

Hsu SC, Sears RL, Lemos RR, et al. Mutations in SLC20A2 are a major cause of familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Neurogenetics. 2013;14:11–22.

Yamada M, Tanaka M, Takagi M, et al. Evaluation of SLC20A2 mutations that cause idiopathic basal ganglia calcification in Japan. Neurology. 2014;82:705–12.

Nicolas G, Pottier C, Maltête D, et al. Mutation of the PDGFRB gene as a cause of idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Neurology. 2013;80:181–7.

Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1276–312.

•• Legati A, Giovannini D, Nicolas G, et al. Mutations in XPR1 cause primary familial brain calcification associated with altered phosphate export. Nat Genet. 2015;47:579–81. This publication is of major importance given that it reports for the first time mutations in XPR1 as a cause of PFBC.

Zhang X, Bogunovic D, Payelle-Brogard B, et al. Human intracellular ISG15 prevents interferon-α/β over-amplification and auto-inflammation. Nature. 2014;517:89–93.

Bogunovic D, Byun M, Durfee LA, et al. Mycobacterial disease and impaired IFN-γ immunity in humans with inherited ISG15 deficiency. Science. 2012;337:1684–8.

•• Tadic V, Westenberger A, Domingo A, et al. Primary familial brain calcification with known gene mutations: a systemic review and challenges of phenotypic characterization. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:460–7. This publication is of major importance since it reports phenotypic differences, including detailed analysis of movement disorders, between cases of PFBC caused by mutation in SLC20A2, PDGFB, and PDGFRB.

• Lemos RR, Ramos EM, Legati A, et al. Update and mutational analysis of SLC20A2: a major cause of primary familial brain calcification. Hum Mutat. 2015;36:489–95. This publication is important since it provides a comprehensive review of mutational analyses of SLC20A2, as a major cause of PFBC.

Hayashi T, Legati A, Nishikawa T, Coppola G. First Japanese family with primary familial brain calcification due to a mutation in the PDGFB gene: an exome analysis study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;69:77–83.

Schottlaender LV, Mencacci N, Koepp M, et al. Interesting clinical features associated with mutations in SLC20A2 gene. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19 Suppl 1:22–89.

Zhang Y, Guo X, Wu A. Association between a novel mutation in SLC20A2 and familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57060.

Chen WJ, Yao XP, Zhang QJ, et al. Novel SLC20A2 mutations identified in southern Chinese patients with idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Gene. 2013;529:159–62.

Kasuga K, Konno T, Saito K, et al. A Japanese family with idiopathic basal ganglia calcification with novel SLC20A2 mutation presenting with late-onset hallucination and delusion. J Neurol. 2014;261:242–4.

Baker M, Strongosky AJ, Sanchez-Contreras MY, et al. SLC20A2 and THAP1 deletion in familial basal ganglia calcification with dystonia. Neurogenetics. 2013;15:23–30.

Zhu M, Zhu X, Wan H, Hong D. Familial IBGC caused by SLC20A2 mutation presenting as paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:353–4.

Nicolas G, Jacquin A, Thauvin-Robinet C, et al. A de novo nonsense PDGFB mutation causing idiopathic basal ganglia calcification with laryngeal dystonia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:1236–8.

•• Nicolas G, Charbonnier C, de Lemos RR, et al. Brain calcification process and phenotypes according to age and sex: lessons from SLC20A2, PDGFB and PDGFRB mutation carriers. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2015;168:586–94. This publication is of major importance since it reports phenotypic differences, including detailed analysis of movement disorders, between cases of PFBC caused by mutation in SLC20A2, PDGFB, and PDGFRB.

Brighina L, Saracchi E, Ferri F, et al. Fahr’s disease linked to a novel SLC20A2 gene mutation manifesting with dynamic aphasia. Neurodegener Dis. 2014;4:133–8.

Gagliardi M, Morelli M, Annesi G, et al. A new SLC20A2 mutation identified in southern Italy family with primary familial brain calcification. Gene. 2015;568:109–11.

Kimura T, Miura T, Aoki K, et al. Familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification: histopathologic features of an autopsied patient with an SLC20A2 mutation. Neuropathology. 2016;36:365–71.

Liu X, Ma G, Zhao Z, et al. Novel mutation of SLC20A2 in a Chinese family with primary familial brain calcification. J Neurol Sci. 2016;360:1–3.

Røsby O, Legati A, Coppola G. Primary familial brain calcification in a Norwegian family, caused by a novel SLC20A2 gene mutation. J Neurol. 2016;263:594–6.

Chung EJ, Cho GN, Kim SJ. A case of paroxysmal kinesiogenic dyskinesia in idiopathic bilateral striopallidodentate calcinosis. Seizure. 2012;21:802–4.

Keogh MJ, Pyle A, Daud D, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of primary familial brain calcification due to a novel mutation in PDGFB. Neurology. 2015;84:1818–20.

Paucar M, Almqvist H, Saeed A, et al. Progressive brain calcifications and signs in a family with the L9R mutation in the PDGFB gene. Neurol Gene. 2016;2:e84.

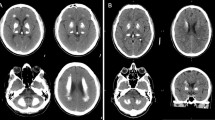

Kostić VS, Lukić-Ječmenica M, Novaković I, et al. Exclusion of linkage to chromosome 14q, 2q37 and 8p21.1-q11.23 in a Serbian family with idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. J Neurol. 2011;258:1637–42.

Boller F, Boller M, Gilbert J. Familial idiopathic cerebral calcifications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977;40:280–5.

Anheim M, López-Sánchez U, Giovannini D, et al. XPR1 mutations are a rare cause of primary familial brain calcification. J Neurol. 2016;263:1559–64.

Moura DA, Oliveira JR. XPR1: a gene linked to primary familial brain calcification might help explain a spectrum of neuropsychiatric disorders. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;57:519–21.

• Marras C, Lang A, van de Warrenburg. Nomenclature of genetic movement disorders: recommendations of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society Task Force. Mov Disord. 2016;31:436–57. This publication is important since it provides recommendations for the new nomenclature of genetic movement disorders, including PFBC.

Wu YW, Hess CP, Singhal NS, et al. Idiopathic basal ganglia calcifications: an atypical presentation of PKAN. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:351–4.

Gandhi SE, Murphy HR, Kellett MW, et al. Novel PTEN mutation with leukoencephalopathy, basal ganglia calcification and action tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;28:163–5.

Toelle SP, Wille D, Schmitt B, et al. Sensory stimulus-sensitive drop attacks and basal ganglia calcification: new findings in a patient with FOLR1 deficiency. Epileptic Disord. 2014;16:88–92.

Van Goethem G, Livingston JH, Warren D, et al. Basal ganglia calcification in a patient with beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;51:843–5.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (grant no. 175090).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Vladimir S. Kostić has received a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (no. 175090) and from the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences, as well as research grants from Stada, Valeant, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Novartis. He has also received lecturing fees from Stada, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Novartis. Igor N. Petrović has received a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (no. 175090) and from the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences, a travel grant from Novartis, and speaker honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim, ElPharma, and GlaxoSmithKlein.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Movement Disorders

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

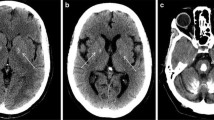

Video 1

Levodopa-responsive parkinsonism–dystonia syndrome in a patient with secondary (postoperative) hypoparathyroidism. Segment 1. Without levodopa. Bilateral (severer on the right) parkinsonism with hypokinesia, rest and postural tremor, and dystonic hand and foot postures. Shuffling gait and positive pull test. Segment 2. Levodopa-induced peak-dose dyskinesia (WMV 51010 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kostić, V.S., Petrović, I.N. Brain Calcification and Movement Disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 17, 2 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0710-9

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0710-9