Abstract

The special characteristics of family firms, such as the owning family’s involvement and control or its strong identification with the business, make creating and preserving a good reputation desirable. Recent studies confirm the positive influence of a firm’s reputation on organizational success and non-financial goals, such as customer retention and social capital. The image and reputation of family firms have been the subject of numerous studies. Despite increasing research intensity, a comprehensive overview of this topic is still lacking. This work provides an inventory of and structure for extant research on the image and reputation of family firms. To this end, a systematic literature analysis has been performed, which includes 73 papers from scientific journals from various business fields. Image and reputation are discussed in different theoretical and geographical contexts. Moreover, this contribution summarizes the ways in which the public perceives family firms and existing influencing factors, courses of action and impacts; in a subsequent step, this work integrates these findings into a model that can serve as starting point for future research activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Corporate reputation is a valuable asset that provides businesses with sustainable competitive advantages and influences their financial performances (Rindova et al. 2005). Consequently, a good corporate reputation is of strategic value to a company (Roberts and Dowling 2002). Customers prefer to choose products from businesses with good reputations, and they are willing to purchase these products at higher prices (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Additionally, businesses with good reputations receive more applications for job openings (Fombrun and Shanley 1990) and find networks (Chandler et al. 2013; Sieger et al. 2011) and financial resources (Yang 2010; Zang 1999) more easily accessible than comparable businesses with worse reputations. Studies suggest that an organization’s reputation directly correlates with its success (Lee and Roh 2012; Roberts and Dowling 2002). Accordingly, reputation is considered a valuable intangible resource (Rindova et al. 2010). In the case of family firms, the owning family constitutes an integral part of the business, which influences the firm’s identity and the image that is projected to outsiders (Zellweger et al. 2012). As family firms generally have long-term orientations and the owning family strongly identifies with the business, the family strives to create a unique image and to acquire a good reputation (Danes et al. 2008; Zellweger et al. 2013). Various rankings frequently feature family firms with the best reputations (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013), which corroborates the importance of image and reputation. However, the relevance of image and reputation is not limited to their impacts on corporate success; they also influence related non-financial goals, such as social status and family interests (Dyer and Whetten 2006; Zellweger et al. 2013).

Over the past two decades, family business research has grown considerably (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011; Xi et al. 2015), demonstrating the relevance of this research field. In particular, the exploration of non-economic goals and their effects on family firm behaviors has moved into the focus of family firm researchers (Chrisman et al. 2010; Xi et al. 2015). Since the mid-1990s, reputation and image of family firms have been the subject of conceptual and empirical studies in various journals, highlighting the growing interest in this topic. However, depending on the research focus, only individual aspects of image and reputation have been investigated, or they have been considered sub-aspects of other research lines. Although some studies explore the factors that influence the image and reputation of family firms, empirical findings on how stakeholders perceive family firms (Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Sageder et al. 2015) and the effects of a family firm’s image and reputation (Memili et al. 2010; Zellweger et al. 2012) remain unclear. As the findings on the topic are published in a variety of fields, such as marketing, finance, entrepreneurship and family business management, research contributions are fragmented and limited, comprising various definitions and multiple theories. Despite intensified research activities on the image and reputation of family firms over the past decade, neither a holistic picture of these important concepts nor an overview of the current state of research exists. So far, review papers have addressed the reputation of family firms as a non-economic goal from a socioemotional wealth perspective (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011) or have discussed it from the founder and family perspective based on articles published in two selected journals over a limited period (Erdem 2010).

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic literature review provides a detailed and comprehensive picture of the image and reputation of family firms from various perspectives. Thus, this article aims to close this research gap. Its key contribution is a systematic literature review of 73 articles published in peer-reviewed journals, which provides an extensive overview of the theoretical and empirical findings on image and reputation of family firms. Following the call of Erdem (2010), this review investigates family firms’ motivations and business practices that contribute to their reputations and the ways in which the public views family firms. In addition, the paper summarizes the consequences of the image and reputation of family firms. A systematic literature review adds value by synthesizing largely unconnected research from various disciplines, countries and theoretical frameworks, which allows the creation of a common knowledge base for future research (Tranfield et al. 2003). Hence, our contributions are fourfold. First, this review contributes to the family business literature by documenting research efforts over the years and illustrating the growing scholarly interest in the image and reputation of family firms over the past decade. Second, the current state of research is identified and structured. In addition, the associations with family firms across countries and stakeholder groups are presented. The factors that motivate family firm owners to develop the firm’s image or enhance its reputation and appropriate actions, along with the effects on financial performance and non-financial benefits, are highlighted. Third, the paper considers family firm heterogeneity by clustering and discussing existing findings according to different types of family firms. This review thus complements the growing body of research that discusses different types of family firms (Dekker et al. 2013; Stockmans et al. 2010). Finally, we contribute to the literature by integrating the research streams into a model that illustrates existing interrelationships. Consequently, existing research gaps are identified, and some fruitful avenues for future research and implications for practitioners are presented.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section defines image and reputation and discusses their significance for family firms. Section 3 explains the methodology that is applied in the literature review. Section 4 examines the characteristics of the consulted articles and their geographical and theoretical contexts and presents the main features of reputation and image in family firms. The subsequent section provides an overview of divergent manifestations in various types of family firms and integrates the research streams into a model that could serve as a foundation for future research. A discussion of implications and limitations concludes the paper.

2 Theoretical basis

2.1 Image, reputation and corporate identity

The literature provides an abundance of definitions for reputation and image, which vary to a considerable extent. Additionally, how image and reputation relate to an organization’s identity is not always clear (Abratt and Kleyn 2012; Brown et al. 2006; Gioia et al. 2000). Drawing on organizational identity theory, an organization’s identity is the anchor point for the “reputation” and “image” constructs. Relatively stable in its core, the organization’s identity cements its characteristics in the minds of its members. However, this identity does react to its environment (Gioia et al. 2000). “Corporate identity provides the central platform upon which corporate communication policies are developed, corporate reputations are built and corporate images and stakeholder identifications/associations with corporations are formed” (Balmer 2008, p. 886). Complementing the organization’s identity, its image is the impression that is projected to stakeholders outside the company (Dyer and Whetten 2006). This image can be a projected image if the company endeavors to communicate its image based on its identity to the exterior (Brown et al. 2006; Gioia et al. 2000). Alternatively, it can also be a desired, future image that is projected internally and externally in form of a vision (Gioia et al. 2000).

Reputation is how outsiders perceive an organization (Dyer and Whetten 2006), including the combined information and assumptions that stakeholders have about it (Brown et al. 2006). Depending on the stakeholder, the organization’s reputation can vary. Investors possess different perceptions than job applicants or customers. Key factors that determine an organization’s reputation are its size, financial success and social responsibility (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Additionally, its activities, as well as media coverage or information about its success or failure, contribute to its reputation (Fombrun and Shanley 1990).

2.2 The importance of image and reputation in family firms

The owning family significantly influences a family firm’s identity (Zellweger et al. 2010). Family firm owners are often actively involved in the management of their firms (Chen et al. 2008), or they select and control the management (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013). Hence, the family’s involvement in the firm’s management contributes to the creation of its identity (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Zellweger et al. 2012). Moreover, due to the overlapping interests of the family and the firm, financial and non-financial difficulties will damage not only earnings and/or invested capital but also the reputation of the firm and the family (Dyer and Whetten 2006; Miller et al. 2008).

Family members that identify with the firm consider it an extension of themselves (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Dyer and Whetten 2006). The firm’s name is often linked to the family name (Craig et al. 2008; Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013). As family members are aware that changing the family is not an option if the company name is stained, they are highly motivated to protect the firm’s and the family’s reputation (Block 2010; Cooper et al. 2005; Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Zellweger et al. 2013). The strong identification of family members with the firm helps build a unique family firm image, which can turn into a competitive advantage and thus support firm performance (Zellweger et al. 2012) and customer loyalty (Binz et al. 2013; Orth and Green 2009; Sageder et al. 2015).

Recent studies have shown that family firms make decisions not only to enhance economic performance but also to achieve socio-emotional goals, such as the projection of a positive image or the preservation of the firm’s and the family’s reputation (Berrone et al. 2010; Block and Wagner 2014; Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013). These goals motivate family firms to undertake activities that benefit non-family stakeholders (Zellweger et al. 2013). For instance, family firms build long-lasting and trusting relationships with their customers (Craig et al. 2008; Levenburg 2006), invest in pollution control (Berrone et al. 2010), avoid major job cuts (Block 2010) and generally act in socially responsible ways to protect their reputations (Dyer and Whetten 2006).

Long-term orientation is one characteristic of family firms (Le Breton-Miller and Miller 2006; Zellweger et al. 2012), which manifests itself in long CEO tenures, long-term investment horizons and the consideration of future generations. Most family business leaders plan to pass on the company to heirs within the family (Le Breton-Miller and Miller 2006). They see their company not only as a sustainable source of income but also as a legacy for the next generation (Dyer and Whetten 2006). Family firm leaders work to create a successful firm in the long run, so they focus on customer loyalty and build long-term relationships with stakeholders (Zellweger et al. 2012). This long-term orientation incentivizes family firms to create a strong image (Zellweger et al. 2012) and to develop a good reputation as an investment for the future (Le Breton-Miller and Miller 2006). The family, the firm’s heritage and future prospects are part of the family firm’s identity, which is intertwined with the corporate brand identity and is communicated to stakeholders in different ways (Micelotta and Raynard 2011). The “familiness”, which is the “unique bundle of resources a particular firm has because of the systems interaction between the family, its individual members, and the business” (Habbershon and Williams 1999, p. 11) can give it a competitive advantage over non-family firms (Craig et al. 2008; Xi et al. 2015).

Family social capital is the supportive social network between the family, customers and the community (Sorenson et al. 2009). Adler and Kwon (2002, p. 23) define social capital as “the goodwill available to individuals or groups”. It includes relationships between individuals and/or organizations and influences the access to a company’s various resources (Sirmon and Hitt 2003). Interdependence and repeated interactions between network members increase social capital (Arregle et al. 2007) and nurture the organization’s reputation. The long-term nature and personal involvement that family ownership entails help establish stable networks with external stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers or capital providers (Arregle et al. 2007; Carney 2005). Social capital facilitates cooperation with network partners and provides access to new business opportunities (Carney 2005; Fan et al. 2012). As a consequence, the family’s reputation is more likely to create long-lasting economic advantages (Anderson and Reeb 2003). The active involvement of family members in community networks helps create a unique family firm image, which constitutes a competitive advantage (Salvato and Melin 2008; Zellweger et al. 2012).

3 Methodology

To investigate the development and current state of research on image and reputation in family firms, a systematic literature review has been conducted. This research approach comprises a systematic, explicit, and reproducible method to identify, appraise, and synthesize extant research (Booth et al. 2011; Fink 2010). It provides an overview of prior research findings to identify similarities and contradictions and to reveal whether findings are consistent with existing knowledge. Moreover, a systematic literature review aims to interpret and connect previous research in new ways or with an innovative perspective and to pinpoint the reasons for conflicting findings. The thus acquired knowledge base intends to help identify existing research gaps, to determine future research demands and to highlight potential avenues for further research (Booth et al. 2011; Jesson et al. 2011). In contrast to traditional literature reviews, systematic reviews are characterized by methodological rigor and thoroughness. Adopting replicable, transparent and comprehensive methods of analysis enhances the legitimacy and objectivity of the resulting evidence and reduces bias (Jesson et al. 2011; Tranfield et al. 2003).

In conducting the systematic literature review, we followed the guidelines suggested by Tranfield et al. (2003). First, the topic and corresponding keywords were defined. Existing family business articles were tagged with the following keywords: “family business*”, “family control*”, “family firm*”, “family led” or “family own*”. These search items were combined with the keywords “image” and “reputation” because they are related constructs and are sometimes used synonymously (Abratt and Kleyn 2012; Brown et al. 2006). Since the corporate brand concept also relates to corporate image and reputation (Balmer 2008), the keyword “brand” was included in the search. Adding asterisks to the search terms ensured that variations, such as “family owned” and “family businesses”, were included in the results. Second, six scientific databases (Ebsco, Emerald, Elsevier, Sage, Web of Science, and Wiley) were searched for corresponding titles, keywords and/or abstracts of articles that were published up until 2015. These sources were screened for their topic fit and with the inclusion criteria defined in Table 1.

The database search resulted in 243 articles that matched the defined search terms in the title, abstract and/or keywords. After removing duplicates, the remaining articles were checked for their publication media and language, as not all database searches could be filtered by publication type. As this review focuses on original contributions, the search was limited to scientific journals with peer-review processes. Moreover, the vast majority of publications in family business research are journal articles (Xi et al. 2015). To provide a quality threshold, the criteria defined by Bouncken et al. (2015) were applied, combining the Academic Journal Guide 2015 of the Chartered Association of Business Schools and the VHB-Jourqual 3 (2015) of the German Academic Association for Business Research. As family firms are also very common in Asia and Australia (La Porta et al. 1999) and reputation is highly relevant for doing business in Asia (Zang 1999), these rankings with emphasis on European and North American journals, were complemented by the ABDC Journal Quality List 2013 of the Australian Business Deans Council, which focuses on Australia and Asia, to ensure the broadest possible spectrum of internationally published articles. Only papers that met one of the following ranking criteria were kept in the sample:

-

A ranking of ≥2 in the Academic Journal Guide 2015

-

A ranking of ≥C in the VHB-Jourqual 3 and ABDC Journal Quality List 2013

Since one of the objectives of this review was to provide a comprehensive international overview, theoretical and empirical articles were included, covering research notes and full papers. In the next step, the papers’ abstracts and contents were screened for their fit with the predefined criteria, resulting in 50 hits. To reduce the risk of overlooking relevant contributions, the references included in these publications were screened for their fit with the topic, as suggested by Fink (2010), and the abstracts were examined using the criteria defined in Table 1. This additional search resulted in 19 articles, which were subsequently included in the literature review. As the image and reputation of family firms constitute an emerging field, attempts have been made to include recent research. To this end, the citations of key articles and the publication lists of researchers in this field have been checked, as recommended by Booth et al. (2011) and Fink (2010), resulting in four additional publications. The articles added also had to meet the quality threshold mentioned above. Two researchers evaluated all the articles. Whenever their assessments diverged, a third researcher was included in the discussion to contribute to the final inclusion decision. Table 2 illustrates the selection process.

In the end, 73 articles were included in the subsequent analysis. In the first step, the empirical results and study characteristics, such as the research design, the theoretical framework or the underlying family firm definition, were collected. In the second step, all the relevant articles were subjected to a content analysis. Two researchers coded the texts to identify various aspects of image and reputation, relationships and interdependencies regarding family firms. The researchers continuously discussed the meanings of the texts (Bouncken et al. 2015; Yin 2014), and, whenever they disagreed, a third researcher reviewed the text and the final decision was negotiated.

4 Results

4.1 Article characteristics

The image and reputation of family firms is a relatively young field of research. The first articles to explore aspects of this topic appeared in the 1990s. As shown in Table 3, almost 90 % of the articles were published in the last decade, and nearly two-thirds have been published since 2010. The 73 articles in the review were published in 43 different journals. The journals with the most publications on the image and reputation of family firms are the Family Business Review (10 articles), Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice (8 articles) and the Journal of Family Business Strategy (7 articles), which together published one-third of all the included articles. The journal’s main focus, as stated on its homepage, is used to assign an article to a research field.

The majority (65 %) of the papers appear in journals that focus on family businesses and entrepreneurship or on general management, discussing a broad spectrum of topics that range from the motivations for developing a family firm’s image and reputation to the economic and non-economic effects of a family firm’s image and reputation. Publications in marketing and communication journals (11 articles) focus on brand building activities and customer loyalty, with most of this publishing activity occurring since 2008. Publications that emphasize finance and accounting (8 articles) highlight the role of a firm’s reputation in investor relations, while publications on business ethics (7 articles) mainly discuss corporate social responsibility in relation to a firm’s reputation. The papers related to the image and reputation of family firms stem from various research fields, which demonstrates the topic’s relevance for several disciplines and reflects the variety of themes in this research area.

As documented in the appendix, most studies take a quantitative approach (42 studies, 58 %). Of these quantitative studies, 23 analyze archival data, whereby most of them address large or stock-listed companies, for which annual reports and other business data are disclosed. A large proportion of these studies (12) originate in the US; of these twelve studies, five focus on companies ranked in the S&P 500 or S&P 1500. Another cluster of archival data analyses consists of studies conducted in Southeast Asia, including Taiwan and Singapore, and in China. In this region, the analysis of archival data is the only method of quantitative data input. Another 19 studies describe mail, telephone or Internet surveys with either stakeholders or managers and/or owners of the company. Qualitative research designs, such as case studies or narrative interviews, are underrepresented (17 studies, 23 %). Eleven articles draw on case studies, of which four describe a single company. Another 14 papers (19 %) are conceptual or theoretical and do not include empirical data analysis.

Regarding the research subject, 23 studies investigate the distinctions between family firms and non-family firms and their effects on different aspects of reputation and image. Although both constructs are relatively stable, they adapt to changing conditions (Gioia et al. 2000). However, most studies are cross-sectional, and only nine are longitudinal, investigating the development of image or reputation over time.

With regard to geographical regions, the research focus lies in industrialized Western countries, where 47 of the 59 empirical studies were conducted. Western Europe is the region with most research activity (22 studies), focused primarily in Spain (5 studies) and Switzerland (4 studies), followed by the US (19 studies). Emerging countries are underrepresented, contributing only nine studies. However, the topic seems to be of some interest in Asia, with nine studies originating from this region. Three research projects cover industrialized countries and emerging countries in cross-country studies. No contributions were available from Africa.

4.2 Theoretical frameworks

Various theoretical lenses have been applied to investigate the image and reputation of family firms. Most papers have a clearly defined theoretical framework; 15 articles employ more than one theory, and only two articles lack a distinguishable framework. Sources are assigned to a theoretical foundation based on the definitions provided by the authors. Five theories, whose key statements regarding image and reputation are presented in this chapter, were employed more than five times. The articles under discussion mostly applied the resource-based view (RBV) as their theoretical framework (17 articles). The RBV considers image and reputation as intangible resources (Craig et al. 2008; Rindova et al. 2010) that affect a company’s competitive position and performance (Habbershon and Williams 1999; Huybrechts et al. 2011). A company’s reputation facilitates the accessibility of resources (Kashmiri and Mahajan 2014; Zang 1999) and new business opportunities (Sieger et al. 2011). A family firm’s special image seems to be a valuable resource, which influences customer loyalty (Orth and Green 2009).

A relatively new concept in family business research is socio-emotional wealth (SEW), which summarizes the total value that families gain from a firm, including non-financial value, such as reputation (Berrone et al. 2010; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011). Since 2010, this concept has been applied in twelve articles, including six conceptual contributions. Striving for goals related to SEW, such as image and reputation, fosters socially responsible behavior in family firms (Berrone et al. 2010; Block and Wagner 2014).

Organizational identity theory is employed eleven times to investigate the image and reputation of family firms. Organizational identity represents the central and enduring values and beliefs that members associate with an organization (Albert and Whetten 1985). Family firm owners, especially founders, often regard their firms as an extension of themselves and as a legacy for the next generation (Dyer and Whetten 2006). The owning family’s strong identification with the firm leads to reputation-related concerns. As a consequence, family members avoid harmful business practices that can damage the company’s reputation (Dyer and Whetten 2006; Zellweger et al. 2013).

Agency theory was used eleven times to investigate the image and reputation of family firms. The basic assumption of agency theory is that owners and managers have divergent goals, which can result in the opportunistic behavior of managers. To align managers’ goals with their own, business owners incur bonding and monitoring costs (agency costs) (Jensen and Meckling 1976). Family firms’ long-term orientation and reputation-related concerns seem to encourage them to value firm survival over the maximization of short-term wealth, which results in fewer agency conflicts and increased resource accessibility (Anderson et al. 2003; Yang 2010).

Brand identity theory (7 articles), which originates from marketing science, defines brand image as the general impression that a customer has of a brand (Keller 1993). These brand associations influence the customers’ decisions (Craig et al. 2008). Family firms are perceived as brands in their own right with specific associations (Krappe et al. 2011). Furthermore, institutional theory (5 articles), transaction cost theory (4 articles), stakeholder theory (4 articles), stewardship theory (3 articles) and several other theoretical frameworks were used to investigate different aspects of the image and reputation of family firms.

Entrepreneurial and family business journals discuss a variety of theories, including RBV (9 articles), SEW (7 articles), organizational identity (7 articles), and agency theory (4 articles). Organizational identity and SEW are commonly applied in family business and entrepreneurial journals to investigate the motives behind socially responsible behavior and reputation-related concerns. Moreover, organizational identity serves as a theoretical background for specific associations with family firms. The RBV is employed to explain influencing factors and the impact of image and reputation. Marketing and communication journals mainly publish articles using brand identity or RBV as a theoretical framework. Brand identity is applied to explore not only associations with family firms but also actions designed to build a favorable brand image, while articles based on RBV postulate that the owning family is an important part of the corporate brand. Contributions in finance and accounting journals focus on access to capital and analyze specific actions, such as dividend payments or disclosure policies, from an agency perspective.

4.3 Family firm definitions

Although family firm research is growing (Xi et al. 2015), no common definition exists for the family firm (Harms 2014; Kraus et al. 2011). Some researchers define a family firm according to ownership and family influence; others consider a firm’s self-perception or familiness to determine whether it is a family firm (Diéguez-Soto et al. 2015). Since these heterogeneous definitions have to be accounted for when interpreting the findings, the family firm definitions of the empirical articles included here were analyzed together with their respective research designs and empirical results. Most articles in this study define a family firm according to ownership and the control exercised by the family. Only one paper relies solely on self-perceptions, as expressed on websites and in interviews. Based on the information specified in the research design or the description of the sample, three main clusters evolved, as presented in Table 4.

The largest cluster consists of family-owned and managed firms, with family ownership of at least 50 % and the family’s active involvement in management or governance. Twelve publications in this cluster also required at least the involvement of a second generation of the family, and nine established the self-perception as a family firm as an additional criterion.

Cluster 2 consists of 20 studies that investigate very large and predominantly stock-listed companies. In terms of ownership, a threshold of at least 5 % seems to draw the line between family firms and non-family firms. Most studies in this group required family control or, more specifically, family members who acted as board members. All 20 studies analyzed archival data, mainly from the US (11 articles) or Asian countries (6 articles); 15 of these studies compared family firms with non-family firms.

The third cluster includes ten studies that investigate stakeholder perceptions of family firms or the family firm’s image through media coverage. Most of these studies did not include a detailed definition in their research design. Regarding the above mentioned impact of different family firm definitions on the results, the respective definition of family firm is included in the following analysis, and the distinctions between various types of family firms are discussed in more detail in Sect. 5.

4.4 Areas of research

4.4.1 Overview of research streams

In the course of the analysis, four content-related research streams crystallized. All contributions matched at least one of these streams; 46 matched several. As illustrated in Table 5, the importance of these research streams has changed over time. Early on, merely influencing factors and consequences were the subject of investigation. Since then, the number of publications that discuss the consequences has remained relatively stable; the number of those that examine influencing factors has increased. The consequences of communicating family ownership to stakeholder groups, such as consumers or employees, have been explored in eight studies, and six studies have been published since 2013. Actions have only been explored since 2004, and they have been increasingly researched in recent years. Associations with family firms, i.e., the specific characteristics of image or reputation, have predominantly interested researchers in the last 8 years.

The 14 conceptual articles focus mainly on the family’s influence on the firm’s image and reputation. Six of these conceptual articles use SEW as a theoretical framework to explain family firms’ motives for pursuing non-financial goals (e.g., Berrone et al. 2012; Cennamo et al. 2012; Zellweger et al. 2013). All six articles were published between 2011 and 2014, and they suggest positive impacts of the firm’s commitment to their stakeholders on the firm’s reputation (e.g., Berrone et al. 2012; Cennamo et al. 2012; Hauswald and Hack 2013; Sharma and Sharma 2011). Regardless of the theoretical lens, a family’s heightened identification with its firm is supposed to increase its desire to protect the firm’s image and reputation (Cennamo et al. 2012; Vardaman and Gondo 2014; Zellweger and Nason 2008), especially when the family is visibly linked to the firm, e.g., when the company shares the family name (Zellweger et al. 2010, 2013). Long-term orientation (Huybrechts et al. 2011; Iyer 1999; Le Breton-Miller and Miller 2006, 2015), social ties (Hoffman et al. 2006; Huybrechts et al. 2011; Iyer 1999) and ethical values (Hoffman et al. 2006; Iyer 1999) are identified as additional drivers of image and reputation building. Reputation is suggested to have positive effects on social capital (Cennamo et al. 2012; Huybrechts et al. 2011), the self-esteem of family members (Hauswald and Hack 2013) and goodwill, as well as status in society (Cennamo et al. 2012; Hoffman et al. 2006). The positive effects of reputation can, in turn, contribute to the firm’s independency and longevity (Cennamo et al. 2012). In addition, the external context of a firm, such as the industry sector (Le Breton-Miller and Miller 2015), culture, the legal framework and other country-level particularities, condition how its reputation can be developed (Hauswald and Hack 2013; Sharma and Sharma 2011).

The following chapters illustrate and categorize the findings of the different research streams by focusing on the 59 empirical studies in this review.

4.4.2 Associations with family firms

Family firms are perceived as a special type of company with typical associations. Some studies characterize family firms as brands in their own right (Craig et al. 2008; Krappe et al. 2011). Table 6 shows the main associations with family firms that have been identified in empirical studies. Most of them are positive and relate to the social capital of family firms.

Family firms are described as socially responsible, trustworthy and customer-oriented firms that have strong ties to their communities. Overall, family firms are regarded as good corporate citizens (Krappe et al. 2011). The tradition and long-term orientation of family firms is also reflected by outside stakeholders. As a consequence, family firms are perceived as persistent and stable, although these properties are sometimes interpreted negatively as stagnation (Krappe et al. 2011). In specific sectors, family firms are negatively perceived by customers for being limited in product selection, for setting comparatively high prices (Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Orth and Green 2009), and for tending to be secretive (Othman et al. 2011). Family firms are also regarded as authentic, small and regionally operating companies (Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Krappe et al. 2011). Potential employees perceive family firms as competitive companies, with committed and socially responsible management, though with less formalized structures and limited career opportunities for non-family members (Covin 1994). However, the recent study of Botero (2014) suggests that the negative perceptions of family firms as employers are rather associated with small family firms.

Most studies that discuss the attributes of family firms were conducted in Western countries, and most of these studies find positive associations with family firms. Deephouse and Jaskiewicz (2013) compare family firms and non-family firms in eight countries from different cultural areas and suggest that family firms generally have better reputations than non-family firms. Botero (2014) found no differences between the US and China in these firms’ attractiveness as employers. By contrast, comparing the images portrayed in mission statements, Blodgett et al. (2011) found that US family firms highlight honesty and integrity, while international family firms emphasize environmentalism, globalism and social responsibility. Drawing on evidence from Russia, Keplinger and Feldbauer-Durstmüller (2012) found that the mass media portrays family firms as immoral, greedy and cheating. Othman et al. (2011) describe family firms in Malaysia as secretive. Therefore, the scientific evidence regarding the influence of culture remains inconclusive. In addition, stakeholders’ characteristics, including their individual experiences with family firms (Covin 1994), their education levels (Covin 1994; Sageder et al. 2015), and their personality traits (Hauswald et al. 2015; Sageder et al. 2015), influence their perceptions of family firms. Hauswald et al. (2015) found that family firms attract applicants who are concerned with the welfare of others and who value conservation rather than those who are open to change or who strive for self-enhancement. Moreover, perceptions seemingly depend on economic circumstances. In times of crisis, family firms appear more attractive to jobseekers (Hauswald et al. 2015), and stability becomes more important to stakeholders (Krappe et al. 2011). Under uncertainty, the image of family firms appears to be a quality reference for consumers (Beck and Kenning 2015).

The majority of studies that investigate the associations with family firms ask participants to provide their personal impressions of typical family-owned and managed firms without giving a specific definition. In most cases, customers or community stakeholders describe their experiences with small, local, family-owned and managed companies in retail or tourism sectors in Western industrialized countries; empirical findings from other geographical regions are scarce. Krappe et al. (2011) found that small and large family firms are perceived differently. While the former are perceived as stagnant and hierarchically structured, large family firms are considered highly competitive. In addition, the limited attractiveness of family firms as employers relates to smaller firm size, which is associated with fewer career opportunities (Botero 2014). However, both types share relational qualities, such as trustworthiness, social responsibility, customer orientation and local embeddedness (Krappe et al. 2011).

4.4.3 Factors that influence image and reputation

The articles included in this review identified different factors that influence a firm’s reputation and image. These factors were clustered into categories, as shown in Table 7. Most of them are specific to family firms (e.g., family influence), while others apply to all types of companies, such as company size and age. Most of the family firm-specific factors create the desire to develop and protect a favorable reputation for the family and the firm and to foster relevant activities.

The family’s involvement is the factor that is most frequently explored in the analyzed papers. The contributions that discuss the differences between family firms and non-family firms found that family ownership and the family’s involvement in management support the development of a favorable reputation. Family ownership is a predictor of responsible behavior toward different stakeholders (e.g., De La Cruz Déniz Déniz and Cabrera Suárez 2005; Dyer and Whetten 2006; Tong 2007). The family’s involvement in the management allows it to build a family firm image (e.g., Gallucci et al. 2015; Memili et al. 2010), to determine the company’s strategy (Basco 2014; Kammerlander and Ganter 2015; Lee and Marshall 2013) and to take action to develop and protect the firm’s reputation (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Miller et al. 2008; Yang 2010; Zang 1999). The influence of family involvement and control was confirmed for different firm sizes and levels of family ownership and control, ranging from 5 to 100 %.

As generally accepted in reputation research, firm characteristics, such as size, age (Fombrun and Shanley 1990) and financial performance (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Roberts and Dowling 2002), are important for building a favorable reputation. The family business literature examined in this review also confirms these factors for family firms (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Dyer and Whetten 2006; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010; Zang 1999) and identifies additional predictors of reputation. Internationalization activities (Micelotta and Raynard 2011) and the industry (Micelotta and Raynard 2011; Westhead 2003) influence the relevance of reputation (Westhead 2003) and affect the strategy for communicating family ownership to stakeholders (Micelotta and Raynard 2011). Fast-growing family firms tend to set gaining reputation as a goal (Lee and Marshall 2013; Xu’nan 2011). The generation involved in the family firm influences reputation-related concerns. While founders aim for growth or performance (Miller et al. 2008), subsequent generations seem to be more concerned about the firm’s reputation in the community and with customers (Miller et al. 2008; Sorenson et al. 2009; Westhead 2003) or minority shareholders (Isakov and Weisskopf 2015). By contrast, anecdotal evidence shows that later generations may be less concerned about investors’ perceptions of reputation because the family might need less external capital to grow (Chen et al. 2010). The founders’ reputation shapes the company’s reputation (Irava and Moores 2010; Kirkwood and Gray 2009), which can be an advantage, though it can also prevent subsequent generations from creating their own reputation (Irava and Moores 2010).

The family’s ethical values and beliefs are passed down through generations (Blombäck and Brunninge 2013). These values determine how family members act toward stakeholders inside and outside the company (Byrom and Lehman 2009; Fernando and Almeida 2012; Kirkwood and Gray 2009; Sorenson et al. 2009). Family values help shape the firm’s image (Presas et al. 2011), and they are reflected in the firm’s level of commitment to its stakeholders, who support its reputation (Uhlaner et al. 2004). Hence, the conceptual model of Cennamo et al. (2012) is confirmed. Adhering to ethical norms helps build enduring network relationships by consistently meeting expectations and obligations (Sorenson et al. 2009). Family firms build strong social ties in their communities (Byrom and Lehman 2009; Uhlaner et al. 2004; Zellweger et al. 2012) and forge close relationships with their customers (Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Levenburg 2006; Presas et al. 2014), employees (Marques et al. 2014; Perrini and Minoja 2008) and business partners (Sieger et al. 2011; Zang 1999). This involvement in the community and in business networks enhances the reputation of the family and the firm (Sorenson et al. 2009). Strong local ties foster responsible behavior toward the community to ensure that a positive public image of the firm is projected (Berrone et al. 2010; Byrom and Lehman 2009; Marques et al. 2014).

The family’s identification with the firm is an important driver of reputation-related concerns. The family’s integration into the firm allows to establish a family-based identity and to create a strong family firm image (Craig et al. 2008; Memili et al. 2010; Zellweger et al. 2012). When the family name is part of the firm’s name, the family seeks to keep the firm’s name unsullied (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010, 2014; Uhlaner et al. 2004). However, the study of Isakov and Weisskopf (2015) in Switzerland found that having the family name as part of the firm’s name had no effect on dividend policy. Family managers who identify strongly with their firms feel personally liable for responsible conduct toward customers and society (Kammerlander and Ganter 2015; Uhlaner et al. 2004). The desire to protect the firm’s reputation influences family managers’ strategic options (Kammerlander and Ganter 2015). If family firm leaders are able to take pride in the firm because of their identification with it, they are encouraged to invest in a positive image and to enhance the firm’s reputation (Zellweger et al. 2012).

Families aim to create value over generations (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2005). The long-term orientation of family firms allows them to generate assets, such as a family firm image, (Miller et al. 2008; Zellweger et al. 2012), to invest in social capital (Uhlaner et al. 2004; Zellweger et al. 2012), and to create a favorable reputation rather than pursuing short-term financial results (Miller et al. 2008).

As some family firms have rich histories and traditions, the family represents continuity for these firms (Micelotta and Raynard 2011). A family’s heritage contributes to the authenticity of a family-based brand (Blombäck and Brunninge 2013), serving as a means to highlight familiness as a part of the brand image (Blombäck and Brunninge 2013; Micelotta and Raynard 2011). Moreover, a long history of trustworthy and socially responsible behavior enhances a firm’s reputation and can ensure the support of its stakeholders (Kashmiri and Mahajan 2014; Perrini and Minoja 2008).

A country’s legal framework conditions how a firm’s reputation can be developed. National legislatures may force companies to implement measures to inform or protect stakeholders, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs, which influence corporate reputation (Blodgett et al. 2011; Othman et al. 2011).

4.4.4 Actions to create a firm’s image and enhance its reputation

Several family firm characteristics encourage the establishment of a family firm’s image and facilitate actions to develop and protect its reputation. Stakeholders’ perceptions shape a company’s reputation (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Actions concerning a firm’s relationship to its customers, employees, investors and other stakeholders are essential for creating a favorable reputation. The articles consulted for this review analyze different actions. Table 8 presents the main clusters of actions.

Strong relationships to stakeholders are essential for developing a reputation. These relationships concern investors, employees and business communities. To satisfy the multitude of interests, various types of activities have been investigated. From the investor perspective, voluntary disclosure policy (Chen et al. 2008), tax aggressiveness (Chen et al. 2010), dividend policy (Isakov and Weisskopf 2015) and earnings management (Xu’nan 2011) have been analyzed. Due to concentrated ownership, family firms are prone to discriminate against external investors. The topic of several studies was family firms’ tendency toward entrenchment, particularly in Asian countries (Sue et al. 2013; Xu’nan 2011, Yang 2010). In a study on Swiss stock-listed family firms, Isakov and Weisskopf (2015) found that dividend payments were generally significantly higher for family firms than for non-family firms. Reputation-related concerns seemingly have the potential to limit expropriation behavior against minority shareholders (Sue et al. 2013; Xu’nan 2011). For business partners, a company’s reputation complements business information and facilitates contracting (Zang 1999). Moreover, a family firm’s relationship with its employees is very important, as it is a reliable employer that creates good working conditions (De la Cruz Déniz Déniz and Cabrera Suárez 2005; Fernando and Almeida 2012; Miller et al. 2008; Perrini and Minoja 2008). The direct involvement of family members, along with trustworthy behavior, creates close relationships with customers and enhances the firm’s reputation (Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Presas et al. 2014).

Many families strongly identify with their firms, which prompts them to act in socially responsible ways (Berrone et al. 2012). Hence, family firms avoid actions that can potentially damage their reputations and attempt to interact responsibly with their stakeholders (Dyer and Whetten 2006). A high level of identification and commitment gives rise to socially responsible activities (Marques et al. 2014; Uhlaner et al. 2004). Family firm owners avoid job cuts (Block 2010) and engage in workplace CSR initiatives (Block and Wagner 2014; Fernando and Almeida 2012; Marques et al. 2014), but they hesitate to act in an employee-oriented way if they believe that these practices might endanger family control or the SEW (Cruz et al. 2014). With regard to the customer dimension of CSR, family firms aim to minimize negative incidents related to their products (Block and Wagner 2014; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2014). In addition, family firms perform better than or at least as well as non-family firms in terms of environmental protection (Berrone et al. 2010; Block and Wagner 2014; Cruz et al. 2014). However, various manifestations of socially responsible behavior exist, ranging from a firm’s philanthropic giving to compensate for its environmental misconduct and to shape its reputation (Du 2015) to a firm’s socially responsible conduct, regardless of economic benefits, that is motivated by family values (De la Cruz Déniz Déniz and Cabrera Suárez 2005). Socially responsible behavior is observed in different types of family firms; however, the company size seems to affect the different manifestations of CSR. While small firms focus on the employee and community dimensions (Marques et al. 2014; Uhlaner et al. 2004), large companies strive to develop their reputations in a broader context by including diversity, product-related and environmental aspects (Block and Wagner 2014; McGuire et al. 2012).

A family firm’s corporate identity is unique because the family is an inimitable component of the firm (Memili et al. 2010). Many family firms build a strong family brand identity (Craig et al. 2008) by integrating their traditions, beliefs and self-perceptions (Blombäck and Ramírez-Pasillas 2012). The corporate brand identity either arises from an intuitive process or is subject to strategic considerations (Blombäck and Ramírez-Pasillas 2012). Different strategies are designed to integrate the family into the firm’s identity to varying degrees, ranging from closely intertwining the family and the firm to clearly focusing on the company and subordinating the family’s role (Micelotta and Raynard 2011). The family firm’s identity constitutes the basis for its corporate reputation if the identity attributes are widely accepted (Zellweger et al. 2013). As family firms are primarily perceived positively, their identities have the potential to create competitive advantages in the market (Zellweger et al. 2012).

The firm’s identity provides the basis for communication with stakeholders (Balmer 2008). The elements of this identity are conveyed through behavior and communication, thereby creating an image and building a reputation (Blombäck and Ramírez-Pasillas 2012). Family firms present their firms’ identities to stakeholders through various channels, such as websites (Blombäck and Brunninge 2013; Gallucci et al. 2015; Micelotta and Raynard 2011), mission statements (Blodgett et al. 2011) and marketing materials (Gallucci et al. 2015). In addition to formalized communication channels, the family and employees are responsible for conveying the firm’s identity and values to customers and other stakeholders (Presas et al. 2011). Firms that decide to promote familiness create their reputation in the market by building on the positive perceptions of family firms (Craig et al. 2008; Presas et al. 2014). Many family firms implement CSR activities, whose communication potentially enhances a firm’s reputation (McGuire et al. 2012; Othman et al. 2011).

Family firms are perceived as customer- and service-oriented entities (Binz et al. 2013). A positive reputation with customers is an important goal for family firms (Danes et al. 2008; Kammerlander and Ganter 2015; Lee and Marshall 2013). Regardless of their strategic orientation, these firms engage in building good relationships with their customers (Basco 2014; Craig et al. 2008). They aim to provide excellent service (Orth and Green 2009) through direct interactions with their customers (Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Uhlaner et al. 2004), to implement new complementary customer services (Levenburg 2006) and to pursue quality and innovation strategies that protect their companies’ reputation with respect to customers (Kammerlander and Ganter 2015). Using the family name in the company name raises concerns regarding product quality (Kashmiri and Mahajan 2014).

4.4.5 Consequences of a firm’s image and reputation

A firm’s image and reputation have impacts on its performance and on non-financial benefits. Table 9 provides the main factor clusters that have been investigated empirically.

The interrelationship of reputation and performance has been well researched in general business studies (e.g., Boyd et al. 2010; Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Lee and Roh 2012; Roberts and Dowling 2002). The family business literature confirms the positive effects of a firm’s reputation on its performance. Actions that enhance its reputation contribute to its performance (Fernando and Almeida 2012; Levenburg 2006). Investments in CSR enhance a firm’s reputation and simultaneously have a positive effect on financial success (Block and Wagner 2014; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010). Again, a family’s identification with the firm, especially when the firm takes its name from the family name, seems to stimulate social and financial performance (Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010). Family firms that build a family firm image achieve better financial results (Craig et al. 2008; Gallucci et al. 2015; Memili et al. 2010; Zellweger et al. 2012). Integrating the firm’s reputation into its strategic goals produces better financial performance and growth (Basco 2014, Lee and Marshall 2013). However, Danes et al. (2008) found that companies that strive to improve their reputations show lower performances, although this finding is contradicted by the longitudinal study of Lee and Marshall (2013). Analyzing the same data set, they show that companies whose strategic goals involve boosting their reputations are younger than the average company and show above-average profit growth. Consequently, Danes et al.’s (2008) findings appear to be driven by age rather than by strategic orientation. The relationship between image, reputation and performance was investigated for all company sizes, predominantly suggesting the positive influence of image and reputation on financial performance.

A good reputation facilitates a firm’s access to resources. In particular, financial capital (equity and debt) is available under better conditions, as empirical studies on large and stock-listed family firms suggest (Anderson et al. 2003; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010; Li 2010; Zang 1999). In addition, evidence has shown that CSR activities enhance a firm’s reputation and increase employee satisfaction (Marques et al. 2014; Perrini and Minoja 2008) and employee loyalty (Perrini and Minoja 2008). Communicating family ownership and control to potential applicants in Germany increased their willingness to join family firms (Hauswald et al. 2015); at the very least, doing so had no negative impact on the firms’ attractiveness as employers in the US and China (Botero 2014).

The creation and communication of a family firm’s image serves as a competitive advantage and contributes to the company’s success (Craig et al. 2008; Zellweger et al. 2012). Family firms aim to develop solid relationships with their customers (Binz et al. 2013; Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Levenburg 2006). Hence, customers generally perceive family firms as customer-oriented and trustworthy organizations (Orth and Green 2009; Sageder et al. 2015), which has positive effects on customer loyalty, customer retention (Binz et al. 2013; Craig et al. 2008), customers’ recommendation to friends (Sageder et al. 2015) and their acceptance of new products (Beck and Kenning 2015). These effects are especially evident in the retail sector and service industry.

While the impacts on performance and customer loyalty are well documented, there is scarce evidence on the effects of reputation on other, non-financial assets. A positive reputation contributes to a firm’s social capital; it assures the support of the community (Perrini and Minoja 2008; Sorenson et al. 2009; Zang 1999), for later generations as well (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2005), and allows the firm access to business networks (Sieger et al. 2011; Zang 1999). It opens the door to new business opportunities (Fernando and Almeida 2012; Sieger et al. 2011) and secures the firm’s status in society (Carrigan and Buckley 2008). While community support is evident for smaller family firms, access to business networks and opportunities are reported for large firms. However, as these clusters include only few studies, these findings must be interpreted with caution.

5 Analysis of findings

5.1 Outcomes in different types of family firms

The articles explored in this literature review used various definitions of the family firm (see Sect. 4.3). Most factors appear to be valid across various family firm types. For instance, increasing size and age influences a company’s reputation positively, regardless of underlying family firm characteristics or definitions. Furthermore, the positive influences of a family’s identification with the firm benefits socially responsible behavior and customer orientation. In general, family firms are perceived as quality-oriented and trustworthy organizations. Moreover, findings on the relationship between reputation and performance are reported for different types of family firms. Nevertheless, some factors show different manifestations depending on the ownership level, the generation involved in the family firm and its size, while others have only been explored for specific family firms. Below, these differences are analyzed further.

The largest cluster of family firms shows a relatively high proportion of family ownership. The family’s influence is well researched in this group. A family that is actively involved in managing the firm shapes its image (e.g., Blombäck and Ramírez-Pasillas 2012; Memili et al. 2010) and takes action to enhance reputation (e.g., Lee and Marshall 2013; Miller et al. 2008). The findings on the generation involved suggest that the founders aim to achieve growth and performance (e.g., Miller et al. 2008; Westhead 2003) and that later generations are seemingly more concerned with their reputations in their immediate surroundings, especially with employees and in the community (e.g., Miller et al. 2008; Marques et al. 2014). The desire for a favorable reputation encourages socially responsible conduct toward the environment and firm employees (e.g., Perrini and Minoja 2008; Uhlaner et al. 2004) and relationship building with stakeholders outside the company (e.g., Marques et al. 2014). The family’s identification with the firm, strong social ties and long-term orientation support the creation of a family firm identity (e.g., Zellweger et al. 2013). A firm with significant family influence derives benefits from building a family firm identity that is based on the family’s values and traditions, which helps differentiate this firm from other companies in the market (e.g., Blombäck and Brunninge 2013; Micelotta and Raynard 2011). Family firm identity has been shown to have positive effects on performance (e.g., Memili et al. 2010; Zellweger et al. 2013) and customer loyalty (e.g., Craig et al. 2008; Orth and Green 2009). This cluster presents no scientific evidence concerning a firm’s reputation with investors and its access to capital.

Regarding the size of the examined companies, two sub-clusters can be identified within this first group. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are examined in 18 studies in Western Europe, the US and other Western-oriented countries. This sub-cluster represents most family firms worldwide (Feldbauer-Durstmüller et al. 2012, Kraus et al. 2012). For this type of company, the motivation for building a family firm image and protecting a firm’s reputation has been well researched. Namely, family members’ strong identification with the firm, social ties and long-term orientation intensify their desire to keep the family name unsullied. Hence, family-managed firms avoid potentially harmful conduct that may damage the reputations of the family and the firm (e.g., Uhlaner et al. 2004) and enhance their reputations in their social and professional environment (e.g., Kirkwood and Gray 2009; Miller et al. 2008). In addition to economic reasons, altruistic motives appear to be important drivers of socially responsible conduct (e.g., Marques et al. 2014, Uhlaner et al. 2004). These firms are seemingly characterized by their strong customer orientations. Securing a good reputation among their customers is often their primary goal (e.g., Basco 2014; Lee and Marshall 2013); they are in direct contact with customers (Presas et al. 2011; Uhlaner et al. 2004) and offer high-quality services (e.g., Levenburg 2006) that foster customer loyalty and performance (e.g., Basco 2014; Levenburg 2006; Orth and Green 2009). As SMEs often lack personal and financial resources for brand building, these firms benefit from building and communicating a family-based image, which constitutes a competitive advantage (Craig et al. 2008). Large family-managed firms are the subject of six studies in different geographical areas; two samples included cross-country data; and five of the six were conducted as case studies. For this type of family firm, relationships with stakeholders, particularly with employees and customers (e.g., Byrom and Lehman 2009; Perrini and Minoja 2008), but also with business partners are seemingly important in developing the firm’s reputation and in facilitating new business opportunities (Fernando and Almeida 2012; Sieger et al. 2011).

The second cluster comprises 20 studies on large, predominantly stock-listed companies with relatively low family ownership levels and/or family representation on the board. The positive influence of family ownership on actions to develop a firm’s reputation has been well researched. Studies on large companies with diversified ownership have used the link between the family name and the firm name to explore the influence of the family’s identification with the firm on reputation-related concerns (e.g., Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2014). In this type of company, relationships with investors and access to capital have been the focus of investigations. Stock-listed companies build relationships with investors through their disclosure policy, dividend payments and earnings management. A family firm’s reputation seemingly limits its tendency to discriminate against minority shareholders (e.g., Chen et al. 2008, 2010; Xu’nan 2011), thereby facilitating access to capital. Consequently, a firm’s reputation is frequently investigated from a financial point of view within this cluster. Large family firms seem to avoid actions that may endanger their reputations through negative press coverage (e.g., Dyer and Whetten 2006; Sue et al. 2013). If, however, other family interests, such as family control, are endangered (Cruz et al. 2014) or if no additional benefit can be found (Isakov and Weisskopf 2015; Othman et al. 2011), reputation building is not pursued at any cost. In contrast to cluster 1, altruistic motives seem of minor importance in cluster 2. In this cluster 16 of the 20 studies compare family firms with non-family firms. Most studies find that family firms are more socially responsible than their non-family counterparts. They show better environmental performances (e.g., Berrone et al. 2010; Block and Wagner 2014) and are more employee friendly (Block and Wagner 2014), avoiding job cuts as much as possible (Block 2010). Similar to family-owned and family-managed firms, large stock-listed family firms seemingly consider product quality important (e.g., Block and Wagner 2014; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010). Reputation building and corresponding actions toward stakeholders have positive effects on the performances and social capital of large, stock-listed companies (e.g., Block and Wagner 2014; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010). The influence of a firm’s previous performance on its reputation is only evident for large or stock-listed companies (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010; Zang 1999). While relationships with investors are well documented for this type of firm, no research has analyzed how to build and communicate a family firm’s image, and evidence regarding the relationships with customers and employees is scarce. In addition, the influence of long-term orientation and the family’s ethical values are neglected, and only one study analyses social ties as influencing factor.

The third cluster includes studies on firms that are perceived as family firms by stakeholders. In most cases, external stakeholders, such as customers, potential job applicants and the public, were questioned without providing a detailed definition of the family firm to respondents. In these studies, family firms are described as small, regionally active firms with strong local ties (e.g., Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Krappe et al. 2011). Overall, most respondents seemed to have small and medium-sized family-managed firms in mind when they imagined a typical family firm. The results of Krappe et al. (2011) and Botero (2014) suggest that size matters when assessing a family firm. Small family firms are perceived as resistant to change, while large ones are perceived as competitive (Krappe et al. 2011). Applicants prefer large firms, whether or not they are family firms (Botero 2014). The attractiveness of family firms for customers in retail sector does not depend on size. Qualitative and quantitative studies reveal that family firms are rated as more trustworthy and customer-oriented firms (e.g., Binz et al. 2013; Carrigan and Buckley 2008), and communicating a family firm’s image leads to higher levels of customer loyalty (e.g., Beck and Kenning 2015; Sageder et al. 2015).

5.2 The overall view

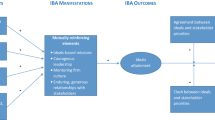

The four research streams for the reputation and image of family firms can be summarized in a comprehensive view. The factors mentioned above are incorporated into the model presented in Fig. 1, which depicts the relationships between the different factors. The relationships suggested by qualitative studies are displayed as dotted lines, while broken lines represent findings from quantitative studies. In many cases, these relationships are documented in qualitative and quantitative studies, which are shown as continuous lines. The thickness of the arrows represents the number of studies.

Influencing factors, such as family involvement, long-term orientation or social ties, increase the desire for a good reputation. Thus, families seek to implement corresponding actions. In particular, when the family name is included in the firm name, reputation-related concerns are considered an important factor. The company’s characteristics, such as size, age and performance, also directly influence its reputation. The older an organization is and the more employees it has, the longer and the more intense its interactions with stakeholders will be, which, in turn, will further spread its reputation. Quantitative and qualitative studies confirm most relationships between influencing factors and actions. Predominantly qualitative research designs suggest the influence of social ties, ethical values, history and tradition on not only firms’ actions to develop their reputation but also on image and reputation directly. Quantitative studies mainly show that the family’s involvement and control and the firm’s characteristics spur reputation- and image-building actions.

Some influencing factors—the firm’s characteristics, the family’s involvement, social ties and long-term orientation—also have direct effects on corporate performance and non-financial benefits. In addition to reputation-related effects, family ownership results in fewer agency conflicts, which facilitates the firm’s access to resources (Anderson et al. 2003). Family owners set long-term goals and develop social ties to improve performance in the long run. These relationships are partly conveyed through the family firm’s image (Craig et al. 2008; Memili et al. 2010; Zellweger et al. 2012). Moreover, influencing factors have a mutual impact on one another. Thus, the long-term orientation of family firms is supposed to foster the development of social ties (Zellweger et al. 2012).

Actions influence organizations’ reputations based on how they are perceived by stakeholders, including employees, customers and the public (Block 2010). Owning families avoid actions that may harm their firms’ reputations (Dyer and Whetten 2006); they are also customer oriented (Binz et al. 2013; Levenburg 2006) and seek build solid relationships with stakeholders (Carrigan and Buckley 2008; Chen et al. 2010; Sorenson et al. 2009). Size seems to be a significant factor in relationship building with stakeholders. In communicating its strong family-based identity to the exterior, a family firm builds its image (Craig et al. 2008) and influences the perceptions of external stakeholders. Family firms mostly possess good reputations and are predominately perceived in a positive light. These positive assumptions mainly refer to a family firm’s social capital, i.e., its social responsibility, trustworthiness, and customer orientation (Binz et al. 2013). An organization’s reputation does not solely positively influence its financial performance. Various non-financial benefits, such as customer retention, social capital and independence, are essential for family firms and stimulate the desire to attain a good reputation (Zellweger et al. 2013). Qualitative and quantitative studies comprehensively document the effect of a firm’s reputation on its financial and non-financial outcomes. Only two case studies explore new business opportunities. The effects of the family firm’s image are evident in the form of customer loyalty and performance.

The impacts of reputation can also change the influencing factors. Financial success can influence the firm’s characteristics, including its size, and can ensure the continuation of family ownership. In addition, prior performance is an important indicator of a firm’s reputation—at least in stock-listed companies (Kashmiri and Mahajan 2010). Meeting non-financial goals is suggested to raise the family’s level of identification with the organization (Sharma and Sharma 2011; Zellweger et al. 2013). A firm’s access to networks due to its reputation, in turn, fosters relationships with business partners and community leaders and increases its social ties (Sieger et al. 2011).

6 Conclusion

6.1 Implications for theory and practice

The reputation and image of family firms is a field that is increasingly gaining attention. It is of crucial importance for family firms and for researchers, as the growing number of publications on this topic demonstrates. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first systematic literature review on this topic. In the past, studies have explored the influencing factors, activities and impacts related to a family firm’s reputation. Some research projects have discussed the public perceptions of family firms. Still, only individual aspects have been investigated; as such, no overarching view has illustrated the correlations of the aforementioned factors with the reputation of family firms and the closely related image of family firms. This literature review of 73 contributions now provides an overview of the state of research on the reputation and image of family firms. The influencing factors and actions necessary to create a firm’s image and to enhance its reputation are identified alongside the financial and non-financial outcomes. This review discusses the distinct perceptions of family firms in different regions and the diverse approaches for investigating this topic in various business disciplines.

Primarily family firms enjoy favorable reputations compared with non-family firms. In particular, stakeholders value the reliability and social responsibility of family firms. All over the world, family firms of various types develop relationships with customers, employees and the community, establish unique images, and acquire reputations for success in the long run. Depending on the ownership level, family control, and size of the firm, some factors manifest themselves in different ways. As family firms are not a uniform phenomenon, considerable differences are found between certain groups. While public reputation and investor relations are important in large, stock-listed family firms, family-owned and managed firms, which are often SMEs, develop and communicate family-based images and focus on their immediate environment to enhance their reputations. The extant evidence has been categorized and merged into a model, which integrates existing research activities and illustrates the key lines of research to provide a broad overview. Furthermore, this review considers the relationships and correlations of individual factors and feedback loops. Assuming that reputation and image will continue to be relevant in family firm research, this model can serve as a starting point for future research projects.

For organizational practice, this paper highlights that a good reputation has positive financial and non-financial effects on family firms and helps create competitive advantages. Firms with direct contact with consumers—for example, in the retail and service industry and tourism—benefit from communicating their family ownership to customers, leading to higher customer loyalty. Most cultures attach positive connotations to family firms. Accordingly, family firms should position themselves to stress their organizational structures to the public. However, in some emerging economies, e.g., Russia and China, family firms seem to be associated with entrenchment, or unethical conduct. Family firms in such an environment should consider communication of family ownership with caution. Reputation helps build social capital and achieve support from business partners, employees and other stakeholders, which can, in the long run, ensure the independence and survival of the organization. This review presents possible courses of action. Acting responsibly within the societal framework is an essential element of good reputation. Hence, family firms should work out, implement, and, above all, communicate selective CSR strategies. Family firms create good working conditions and are stable employers. Recent studies show that family firms have the potential to attract job applicants. However, the small size of many family firms and their lack of career opportunities and formalized structures can be a disadvantage when recruiting new employees. The communication of family influence attracts certain types of applicants. Family firms appeal more to people who appreciate stable conditions than candidates who are open to change. Especially in times of crisis, employees appreciate the stable conditions of family firms. Thus, family firms should consider this when recruiting personnel or investing in employee development strategies.

6.2 Limitations and future research

The search was conducted using six scientific databases, entering relevant keywords and exploring the references of previously identified contributions as well as the publication lists of researchers in this field. Despite all these efforts, the literature search may not have captured all the articles that address the subject of this review. Books and journals with pure practitioner orientations were not part of this analysis. A team of researchers have carefully clustered the findings of the analyzed papers according to replicable criteria. Nevertheless, other researchers might have clustered factors differently.

Some influencing factors, such as social relations and the influence of the generations or different types of families, e.g., a patchwork family or multigenerational kinship (Klein 2008), on the organization have thus far been mostly neglected. Li (2010), Sue et al. (2013) and Yang (2010) discuss the regulatory function of a firm’s reputation in regions with lower legal security. Future studies could investigate these issues in the family firm context. Negative deviations from normal behavior diminish the stakeholders’ social acceptance of firms, which is crucial for their legitimacy (Deephouse and Carter 2005). Concerns about the legitimacy of family firms encourage families to act as good corporate citizens (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013). Legitimacy is discussed as a construct that is related to reputation, but it has not yet been empirically investigated in relation to family firms. SEW is an up-coming concept (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011; Xi et al. 2015). The empirical studies that apply the SEW perspective mainly focus on influencing factors, such as family involvement, and on socially responsible actions. Using this theoretical lens, evidence of related consequences is scarce, opening an interesting research path for the future.