Abstract

Corporate reputation is widely acknowledged to contribute to business success by academics and business executives. Despite the importance of corporate reputation in all markets, we lack sufficient research into what reputation might mean in the context of companies in developing countries. This paper addresses this lingering gap in the literature by investigating the dimensions that make service organisations reputable from the perspective of four primary stakeholder groups of two large service organisations. The paper also sought to determine whether the same reputation dimensions apply to service organisations in general, or whether they differ according to the type of service organisation. Empirical data were sourced using the mixed-method approach, and analysis revealed 16 items across 6 dimensions that constitute the reputation of service organisations. The study also found that there is not much difference between the reputation dimensions of two organisations used in this study. However, it reveals major differences between the dimensions derived from the developing country context, and those derived from developed contexts. This illustrates that context-specific reputation measures can emerge which are important in understanding how reputation is created and can be managed. Consequently, it underscores the need for more scientific researches into reputation dimensions in different contexts (countries and organisations).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increased competition in today’s business environment has made it imperative to identify the drivers of sustainable competitive advantage. These drivers are not limited to tangible assets alone, but also include the intangibles such as corporate reputation. More than ever before, organisations realise that stakeholders are more attracted to organisations with a strong reputation; thus, corporate reputation has become a must-have for any organisation that desires to be profitable, competitive and sustainable. This is evident in how organisations are increasingly investing in their product/service quality, employee engagement, stakeholder relations and corporate communications activities, as part of the efforts to boost their reputation.

Several empirical studies have explored the significance of corporate reputation in different kinds of organisations (products and services), as well as the factors that favourably contribute to the reputation of these organisations. There is an evidence that a positive reputation offers a competitive advantage, increases patronage, encourages shareholders to invest, attracts good staff, retains customers and protects the organisation from excessive scrutiny by making the media secondary definers (Bergh et al. 2010; Adeosun and Ganiyu 2013; Gardberg and Fombrun 2002; Carreras et al. 2013). On the other hand, unfavourable reputation can decrease stakeholders’ confidence in the organisation, which can consequently threaten the organisation’s legitimacy and may lead to reduced profit (Adeosun and Ganiyu 2013).

Although these studies indicate that a favourable reputation is significant in every organisation, they also suggest that the impact of a favourable reputation is more significant in certain types of organisations than others due to various factors. For instance, some authors (Balan and Schiopoiu 2017; Trotta and Cavallaro 2012; Wang et al. 2003) believe that the impact of corporate reputation is more significant for service organisations due to the intangible nature of services—a situation whereby stakeholders cannot feel, touch or see services prior to patronage. Unlike product-based organisations where stakeholders can physically inspect a product before making a purchase, services are not physical. Hence, stakeholders have to rely on the organisation’s reputation, which could be in terms of its media rankings/ratings, testimonials or positive word-of-mouth, to inform their patronage decision.

However, although the attention given to corporate reputation has significantly increased over the years, research into the dimensions of reputation has not evolved at the same rate (Carroll 2016; Feldman et al. 2014; Kitchen and Laurence 2003). Adding to this problem, the few studies on the reputation dimensions of service organisations are usually supported with evidence from developed countries, and reputation scholars (Soleimani et al. 2014; Trotta and Cavallaro 2012; Kanto et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2003) have emphasised how the dimensions of corporate reputation differ based on the context within which they are being investigated. Hence, generalising the findings from developed countries to developing countries may be inaccurate and problematic.

Based on this, this article investigates what constitute the reputation dimensions of service organisations in a developing country context, Nigeria. It investigates these dimensions from the perspective of four primary and relevant stakeholder groups (customers, employees, regulators and business communication executives) of two large service organisations—a bank and a mobile service provider. The outcome of this study is expected to reveal if/what difference exists in the reputation dimensions contained in existing instruments such as the AMAC, RQ and those derived from this study context. The outcome of the study will be useful to illustrate how context-specific reputation measures can be. It identifies dimensions and measurement items not used in other measures, a finding which may be useful to others.

The concept of corporate reputation

There are several perspectives towards corporate reputation, both in terms of its definition and its dimensions, so much so that having a universal definition or dimensions is almost impossible. This is mainly attributed to the fact that corporate reputation draw attention from several academic disciplines. It is also attributed to the fact that different researchers investigate its dimensions in different types of organisations. We see a difference in the reputation dimensions and items derived from studies that explored a product-based organisation when compared with those derived from a service-based organisation or even studies that used both product and service companies (see Wepener and Boshoff 2015; Caruana and Chircop 2000; Ponzi et al. 2011; Davies et al. 2018; Trotta and Cavallaro 2012). This may be tied to the fact that the different kind of organisations have different offerings and missions, as well as different key stakeholder groups.

It is, however, observed that despite the myriad of definitions, most scholars seem to agree that corporate reputation results from stakeholders’ collective perception or assessment of an organisation. We adopt Olmedo-Cifuentes and Martínez-León’s (2011) definition of corporate reputation because it encapsulates the rationale of this study to identify the dimensions that create value for an organisation (in this case, services) and favourably influence stakeholders’ perception. Olmedo-Cifuentes and Martínez-León (2011, p. 79), thus, define corporate reputation as follows:

“the estimate of the overall perception different stakeholders have about a company, evaluated through a set of dimensions and attributes that create value that are linked to the organisation and distinguish it from the rest”.

Given that a favourable corporate reputation can only be achieved by stakeholders’ positive perception and evaluation of an organisation, it becomes imperative to identify the dimensions that influence these perceptions for organisations to align their activities accordingly. The challenge, however, is that the dimensions that make organisations reputable vary based on several factors like the country within which the investigation is conducted, cultural differences, the type of organisation investigated, stakeholder groups used, etc. For instance, Aperia et al. (2004) used the Reputation Quotient (RQ) to investigate how citizens in each of the three Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Norway and Denmark) will assess the dimensions contained in the instrument. Despite the cultural similarities in the Scandinavian countries, the level of importance of each dimension contained in the RQ varied across the countries.

Besides, Wepener and Boshoff (2015) and Trotta and Cavallaro (2012) in their respective country context explored the dimensions that make service organisations reputable and they both had different outcomes. Using a bank and an airline operating within the South African business context, Wepener and Boshoff (2015) found ‘Emotional appeal, Corporate performance, Social engagement, Good employer and Service points’ as the reputation dimensions. While Trotta and Cavallaro (2012) investigated the reputation dimensions of a bank in the Italian business context and found the dimensions to be ‘the organisation’s role (in terms of its vision, mission, and leadership); its responsibility in society; relationships with internal and external stakeholders; its result (in terms of its financial performance and quality of service); and regulatory compliance’. The difference in the outcomes of the aforementioned studies, even though both investigations focused on service organisations, support our standpoint that reputation dimensions differ according to the context within which they are being investigated.

The foregoing show that indeed, various factors influence the dimensions of corporate reputation, and applying the reputation dimensions derived from one context to another context may not produce an accurate measure of corporate reputation. Therefore, as is the case in this study, reputation dimensions must be investigated in the context (industry and country) within which the organisation is situated.

Measuring corporate reputation

Given the significance of corporate reputation especially in the service industry, identifying the dimensions that contribute to, or influence a favourable reputation is of vital importance. The establishment of the precise reputation dimensions enables the accurate measurement of corporate reputation, and Dowling and Gardberg (2012) emphasise the importance of measuring corporate reputation in a scientific way in order for organisations to know their reputation score.

Over time, some instruments for measuring corporate reputation have been developed. The most popular ones include the Fortune’s Most Admired Company (FMAC) List, the Reputation Quotient (RQ), RepTrak, Corporate Personality Scale, and the Stakeholder Performance Indicator and Relationship Improvement Tool (SPIRIT). While some of these instruments are often used (e.g. the RQ and RepTrak), they have been criticised for (1) measuring reputation from a single stakeholder perspective, e.g. the RQ (Wartick 2002). (2) Focusing only on an organisation’s financial qualities, e.g. the FMAC (Feldman et al. 2014) and (3) their inability to provide ways to assess how an organisation can develop its reputation (Money and Hillenbrand, 2006). Also, some studies found that the dimensions in these existing instruments do not have cross-cultural validity which would allow for international comparability (Feldman et al. 2014, p. 59), and they are also not industry specific (Dowling and Gardberg 2012; Trotta and Cavallaro 2012; Kanto et al. 2015; Chun 2005). That is, they were developed for all types of organisations (both product and services based such as manufacturing, aviation, telecommunication, and non-profit organisations).

Furthermore, although the RepTrak pulse (Ponzi et al. 2011) and three dimensions of Davies et al. (2018) affect-based measure have been argued to be universally relevant, dimensions such as ‘looks like a good investment’ or ‘seem profitable’ are clearly not relevant to not-for-profit organisations. This dramatic difference is also evident in the criteria used in measuring the reputation of tertiary institutions compared with AMAC, RepTrak or the RQ.

The gaps in these instruments can lead to inaccurate measurements of corporate reputation because various stakeholders have different expectations and would assess an organisation differently. This is evident in the 2013 South Africa RepTrak survey that indicated ‘Products/Services and Innovation’ as the most important dimensions of reputation, whereas the Global survey indicated ‘Citizenship, Workplace and Governance’ as the most important dimensions (Global RepTrak 2013; South Africa RepTrak Pulse 2013). The difference or inaccuracy that comes with using the generic measurement instruments is also seen in the studies of Kanto et al. (2015) and Trotta and Cavallaro (2012). Kanto et al. (2015, p. 414) examined the suitability of the Reputation Quotient when applied to Malaysian banking stakeholders and found that of the six dimensions of reputation in the instrument, ‘workplace environment’ was not a dimension considered by stakeholders of Malaysian banks, whereas Trotta and Cavallaro (2012, p. 28) found the ‘workplace environment’ to be a key reputation dimension to stakeholders of Italian banks.

The difference in the reputation dimensions considered by stakeholders is not unique to the banking industry, as it is also evident in the telecommunication industry. Shamma and Hassan (2009) explored the reputation dimensions in the United States telecommunication industry and found corporate social responsibility (CSR) to be an insignificant dimension to stakeholders, while Yasin and Bozbay (2011) and Awang and Jusoff (2009) found CSR to be a significant dimension for the telecommunication industry in Turkey and Malaysia respectively.

More so, if reputation dimensions varied among employees and customers of the same organisation (see Chun and Davies 2006) and even among types of employees (see Olmedo-Cifuantes et al. 2014), how much more the reputation dimensions that will be derived from different countries.

The different outcomes of the aforementioned studies validate scholars’ (Davies 2011; Balmer and Greyser 2006) assertion that a scale developed in one context (e.g. in one type of industry, with one stakeholder group, or one country) should not be considered valid in different contexts without a thorough investigation. Corporate reputation must be measured based on the dimensions identified in the industry and country the companies operate. “Doing so may limit generalisability, but it will improve validity” (Feldman et al. 2014, p. 59).

Research questions

Based on the discussions in the preceding sections, this study investigates what constitute the dimensions of reputation for service organisations in a developing country context, Nigeria, and poses the following research question:

-

What are the dimensions considered by stakeholders of the selected service organisations when evaluating corporate reputation?

To further determine whether the same reputation dimensions are applicable to service organisations in general, or whether they also differ according to the type of service organisation, the following research questions were posed:

-

What are the reputation dimensions considered by stakeholders of a bank?

-

What are the reputation dimensions considered by stakeholders of a service provider?

Methodology

The mixed-method approach (MMA) was used for data collection and the design followed the exploratory sequential mixed method. That is, the qualitative data collection and analysis were first conducted and its outcome informed the quantitative data collection and analysis. The qualitative method, using face-to-face semi-structured interviews, provided a thorough understanding of the dimensions stakeholders consider when evaluating the service organisations and led to the identification of the reputation dimensions. Before then, an extensive review of literature on existing corporate reputation measurement instruments, as well as a review of studies that explored reputation dimensions in service organisations was conducted.

The dimensions identified from literature and interviews then led to the quantitative enquiry that used questionnaire as the instrument for data collection. The quantitative method was used to streamline the dimensions and determine the most relevant to stakeholders. It also eliminated the issue of bias by providing results that did not only emanate from the researcher’s interpretation of interviewees’ responses, but results that are backed by a rigorous, objective scientific process and analysis.

Two large service organisations in Nigeria, a commercial bank and a mobile service provider were used as the sample organisations because they are highly patronised and used by stakeholders almost on a daily basis. Hence, stakeholders are well informed of these organisations. Data were sourced from four primary stakeholder groups of both organisations namely customers, employees, regulators, and business communication executives. The selected stakeholder groups for the study are crucial because they are primary stakeholder groups of both organisations, and their perceptions and evaluations have the most influence on the corporate reputation. Also, using multiple stakeholder groups in this investigation is hinged on the study’s standpoint that reputation results from the aggregate perception and evaluation of all stakeholders; hence, investigating corporate reputation dimensions from the perspective of only one stakeholder group is inadequate.

Stakeholders for the face-to-face semi-structured interviews were selected using the purposive, non-probability sampling technique. This technique was appropriate for the study as the importance of choosing respondents who will provide intelligent and detailed responses to questions is well emphasised by Creswell (2014). Interviewees were, thus, selected based on certain features like their knowledge of corporate reputation, as well as their knowledge of, and affiliation with the selected organisations in order to provide in-depth and relevant answers to questions.

Selection of interviewees for this study was done in three stages. In the first stage, the authors consulted with the contact person in each organisation (one human resource staff, and one settlement and reconciliation staff) to compile a list of willing interviewees after briefing them on the research topic and purpose of the interview. After that, the authors evaluated the suitability of the potential interviewees for the study and made a shortlist based on their work experience, expertise, and knowledge of corporate reputation in order to have rich data. In the third stage, formal interview request emails were sent to shortlisted interviewees detailing the nature of the interview, its purpose, timing, and their role in the research process. A list of confirmed interviewees was then derived.

A total of fifteen (15) interviews were conducted. The interviewees consisted of two customers of each organisation (total = 4); two employees of each organisation (total = 4), 2 communication staff of each organisation (total = 4); two regulators of a bank and one regulator of a mobile service provider (total = 3).

On the other hand, respondents for the quantitative study were selected using the stratified random sampling since the study specifically sought to investigate the dimensions of reputation from the perspective of only the selected four stakeholder groups, and the sample size was specified. Using other sampling techniques might make those who are not the target stakeholders fill the questionnaire; hence, this technique was, therefore, appropriate as it ensured the questionnaire was filled by those it was intended for, while giving each stratum an equal chance of being selected, and by so doing, eliminated bias.

For instance, in the case of ‘employees’, regulators and communication staff, the questionnaire was taken to their respective organisations and distributed to those who were present and willing to take the survey. Administering the questionnaires to customer was, however, more tasking as the authors had to first enquire whether or not they patronised the selected organisations. To simplify this process, the questionnaires were taken to a university that had within her premise, a branch of the bank, and a customer service centre of the mobile service provider. This means that the bank and the MSP have a large subscriber base in this location. The questionnaires were then distributed to masters’ students at the University who are customers of the bank and mobile service provider. This method was used in the two phases of the quantitative process.

Qualitative result

As stated earlier, an in-depth review of literature that explored what constitutes reputation in service organisations was first conducted prior to conducting the interviews. 12 reputation dimensions and 26 items explaining the dimensions were derived from literature namely: ‘Quality of service, Employee welfare, Corporate social responsibility, Compliance with regulatory standards, Ethical culture, management and leadership, Trustworthiness, Media relations, Corporate communication, Governance, Corporate brand, Emotional appeal, and Workplace environment’.

From the 15 semi-structured interviews conducted with stakeholders, 13 reputation dimensions and 38 items emerged. The dimensions and their assigned codes are Service quality (SEQ), Issue management (ISM), Corporate Communication (COC), Branding (BRA), Customer Relations (CRL), Financial Performance (FIP), Employee Engagement and Welfare (EEW), Innovation (INN), Social Responsibility (SOR), Empathy (EMP), Risk Management (RIM), Regulatory Compliance (REC) and Trustworthiness (TRT).

Some of these 13 dimensions derived from the interviews bore similarities with those identified from literature. However, 4 new dimensions that are not contained in the literature emerged from the interviews as important potential contribution. They are Risk management, Empathy, Issue management, and Customer relations. Also, three dimensions identified from literature were not mentioned in any way or form by any stakeholder interviewed in this study. The dimensions are Governance and Leadership (GOL), Emotional Appeal (EMA), and Media Relations (MER). These 3 dimensions were, however, still included in the study, and in total, 16 dimensions and 64 items emerged following the lead from the literature and interviews.

Quantitative result—phase 1

A close-ended 5-point Likert scale questionnaire was developed based on the outcome of the qualitative study. The response scale included strongly agree, agree, neutral, strongly disagree and disagree. The questionnaire was pre-tested among 100 respondents of both organisations, which is 50 copies were administered to the bank’s respondents and 50 copies to respondents of the MSP. The questionnaire distribution breakdown for both organisations was 15 copies to customers (total, 30), 15 to employees (total, 30), 10 copies to regulators (total, 20) and 10 copies to communication staff (total, 20). Based on the context within which the study was conducted, self-administration of the questionnaire was most appropriate as it ensured a high response rate and quick return. It was also appropriate since the sample size was manageable.

Eighty-eight copies of questionnaires were recovered, and this signified an 88% return rate which is considered very high and the data derived are also considered useful. A reliability test was conducted on the recovered questionnaires using the Cronbach alpha. The Cronbach coefficient alpha (α) is generally regarded as the basic statistical technique for evaluating a measure’s reliability based on its internal consistency (Taber 2018). Internal consistency is the average correlation of a set of items measuring a construct. That is, it specifies the degree to which the items adequately capture or explain the construct. The Cronbach alpha can be between 0.0 and 1.0, but the rule of thumb is that a construct (dimension) must have a coefficient alpha of 0.70 or higher to be considered reliable (Taber 2018; Cooper and Schindler 2007). Most of the dimensions in the questionnaire had a coefficient alpha greater than the acceptable mark, 0.70, which indicates that the items adequately explain the dimension. Those that had a low coefficient were either restructured or eliminated.

The modified version of the questionnaire was then sent to industry practitioners working in top organisations and senior academics in the corporate communication and corporate reputation field. This was done to ensure that the questionnaire was suitable for the intended investigation and also to get expert recommendation on the dimensions or items to include, regroup, merge or delete. One of the recommendations was that the ‘media relations’ dimension be changed to ‘media reputation’ since its underlying items describe the latter construct better. The feedback from these experts aided in further modifying the questionnaire, and this process is used to achieve face validity in scientific research (Bolarinwa 2015; Mohajan 2017). Overall, the refined questionnaire contained 48 items across 16 dimensions.

Quantitative result—phase 2

The refined questionnaire was re-administered to a larger population of 220 respondents (customers, employees, regulators and communication staff) and was equally shared among respondents of both organisations. That is, 110 copies for the bank and 110 for the mobile service provider. Due to the stakeholders’ dynamics, the questionnaire was not equally shared among the four stakeholder groups since some stakeholder groups were naturally greater in number, and more accessible than others. 50 copies of questionnaire were administered to customers of the bank, 50 copies to employees and 5 copies each to regulators and corporate communicators of the bank. The same distribution method was used for stakeholders of the mobile service provider.

A total of 106 questionnaires were recovered from respondents of the bank and 102 from respondents of the mobile service provider. Cumulatively, all the questionnaires were recovered from regulators and corporate communicators, 92 copies were recovered from customers and 96 from employees. This brought the total number of recovered questionnaires to 208, signifying a 94.5% response rate.

To streamline and identify the dimensions and items to those that are most relevant, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using the Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) was conducted. One of the rules for conducting exploratory factor analysis is that there must be a minimum sample of 150 (Kyriazos 2018; Izquierdo et al. 2014), and the recovered data from the sample population surpassed this condition.

Prior to conducting the EFA, the KMO and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was used to determine the suitability of factor analysis based on the sample responses. This is the required first step when conducting EFA (Izquierdo et al. 2014). The value ‘Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy’ is expected to be greater than 0.5, anything higher than 0.5 is better. The test result returned a KMO of 0.585 which established that conducting the exploratory factor analysis was appropriate (see Table 1). Both the Bartlett’s Test and the KMO results also indicated that there was appropriate correlation (covariance) in the data to proceed with the factor analysis. The last value in the table is the significance which is expected to be a value lower than 0.001 as we have it in Table 1.

The EFA using the Principal Axis Factoring technique and an orthogonal rotation (varimax) was then performed on the data. Factor analysis generates factor loadings (communalities) that signify the relationships between an item and each factor (dimension). Factor loadings ≥ 0.50 are essential in factor analysis to ensure that the variance from the item loads primarily onto the factor being considered (Hair et al. 2010).

Table 2 shows the factor loadings of each of the 48 items across the 16 dimensions. Only factor loadings ≥ 0.5 were extracted and considered relevant to the corporate reputation of service organisations. Based on this, ‘Empathy’ and ‘Risk management’ dimensions were eliminated since their items loading was ≤ 0.5. Thirteen other items were also eliminated since their factor loadings were below the minimum acceptable value. This brought the total number of significant corporate reputation items to 31 across 14 dimensions.

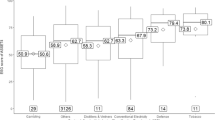

The Eigenvalue criteria were then used to determine the most relevant reputation dimensions out of the 14 dimensions that emerged after the EFA. Dimensions with initial Eigenvalues ≥ 1.0 are considered significant and retained, while those with Eigenvalues less than 1.0 are eliminated (Hair et al. 2010). 6 out of the 14 dimensions emerged as the final reputation dimensions for service organisations. The dimensions in their respective order are issue management, service quality, corporate communication, social responsibility, branding and trustworthiness.

The first dimension, issue management, returned an initial Eigenvalue of 2.837, and this explained 21.823% of the variance in the data (see Table 3). This is the most significant reputation dimension for service organisations based on the analysis of stakeholders’ responses. The second dimension, service quality, had an initial Eigenvalue of 1.678, which explains 12.905% of the variance in the data. Dimensions 3, 4, 5 and 6 had initial Eigenvalues of 1.330, 1.251, 1.119 and 1.033, and they explained 10.231%, 9.624%, 8.607% and 7.945% of the variance, respectively. The six dimensions and their corresponding items explain 71.136% of the variance in the data.

Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings in Table 3 are calculated in the same way as the ‘Initial Eigenvalues’, except that the extracted sums values are based on the common variance. Hence, the extracted sum will always be lower than the initial values since they are based on the common variance, which is always lower than the total variance. The 6 reputation dimensions and their corresponding items are presented in Table 4.

Reputation dimensions for banks and MSPS

To determine whether the same reputation dimensions can be applied to both banks and mobile service providers, a Multiple Regression Analysis (MRA) was performed using the result of the EFA. Multiple regression analysis is the most suitable technique for analysing the relationship between a single dependent variable (e.g. corporate reputation) and several independent variables (e.g. the dimensions of corporate reputation). The result of the MRA (see Tables 5 and 6) shows the significance and effect of each dimension to the corporate reputation of each service organisation used in this study. The rule of thumb is when the ‘significance’ (p value) is < 0.05, there is significant relationship between the dimension and corporate reputation. The ‘Beta’ in the table informs us of the contribution/impact of each of the independent variable to the dependent variable (Corporate Reputation).

The result as shown in Table 5 indicates that stakeholders of the bank consider all but one (Governance and leadership) of the dimensions in their evaluation of the corporate reputation. Although 13 out of 14 reputation dimensions are significant to corporate reputation, regulatory compliance (beta = 2.703, p value = < 0.05) has the most impact on the reputation of a bank. This is followed by trustworthiness (beta = 1.640, p value = < 0.05), service quality (beta = 1.342, p value = < 0.05), corporate communication (beta = 1.316, p value = < 0.05) and thereafter, social responsibility (beta = 1.296, p value = < 0.05).

This indicates that a drop in regulatory compliance, trustworthiness, service quality, corporate communication and social responsibility efforts of a bank as perceived by stakeholders can lead to a corresponding reduction of the bank’s reputation by 2.703, 1.640, 1.342, 1.316 and 1.296 units, respectively. In other words, the corporate reputation of a bank is significantly reduced following stakeholders’ negative perception or evaluation of its regulatory compliance, trustworthiness, service quality, corporate communication and social responsibility efforts.

On the other hand, all the reputation dimensions except ‘media reputation’ (MER) are considered relevant by stakeholders of the MSP since its p value is greater than 0.05 (see Table 6). The Beta in the table indicates that service quality (beta = 0.283, p value = < 0.05) has the most impact on the reputation of mobile service providers. This is followed by employee engagement and welfare (beta = 0.281, p value = < 0.05), emotional appeal (beta = 0.199, P value = < 0.05), social responsibility (beta = 0.185, P value = < 0.05) and customer relations (beta = 0.172, p value = < 0.05).

This also indicate that a decrease in stakeholders’ perception of a mobile service provider’s quality of service, employee engagement and welfare, emotional appeal, social responsibility and customer relations, can lead to a decrease in the organisation’s reputation by 0.283, 0.281,0.199, 0.185, and 0.172 units, respectively. Therefore, the corporate reputation of a mobile service provider is greatly reduced following stakeholders’ negative perception or evaluation of its service quality, employee engagement and welfare, emotional appeal, social responsibility and customer relations.

The foregoing shows that there is minimal difference in the reputation dimensions considered by stakeholders of a bank and stakeholders of a mobile service provider, where the difference lies is in the order of importance and impact level of the reputation dimensions to each organisation. Thus, based on the findings, it can be concluded that the reputation dimensions for a service sector like banks can be applied to another service sector like mobile service providers.

Discussion

The macro-economic setbacks of the last two decades came with a broadening of responsibilities that forced organisations to look beyond their product/service offering, to a more stakeholder approach in order to be reputable. Insights from existing studies emphasise how crucial it is for organisations, especially service organisations to identify its reputation drivers in order to manage it successfully. To assist such organisations, this study identified 16 items across 6 reputation dimensions for service organisations following an extensive mixed-method investigation among four primary stakeholder groups.

The outcome of this study illustrates the benefits of deriving context-specific reputation measures. For example, ‘issue management’ emerged as the most important reputation dimension for service organisations even though it is not seen in any existing study on reputation dimensions. The closest to it is seen in Trotta and Cavallaro’s (2012) study in which ‘complaints management’ is identified as an item under ‘regulatory compliance’. Since no explanation was given about the item or dimension, it is uncertain whether the ‘complaint management’ refers to how the bank deals with complaints raised by the regulators, or how regulators perceive the bank’s effort in managing complaints raised by stakeholders. Exploring context-specific reputation measures, therefore, allowed for the identification of a crucial dimension that otherwise, would have been absent if reputation was solely measured with any of the widely used measurement instruments (e.g. RepTrak and RQ).

The strength of the issue management dimension may be explained by the increasing poor management of most organisations in this study context. Several reports (Benson 2019; NairaMetrics 2018; Akintade 2019; Pulse 2019), including social media, reflect how customers are dissatisfied with how most organisations manage issues and complaints from stakeholders. This has even led to the collapse of some of these organisations (Pulse 2019; TheGuardian 2018; Fakoyejo 2019). Hence, it is not surprising that the issue management dimension alone accounts for 21.823% of corporate reputation, while the other five dimensions account for 49.313% of corporate reputation. The strength of the issue management dimension may also be explained by the unique nature of service organisations. Zeithaml et al. (2009) describe it as a situation whereby service provision (production) and service experience (delivery) are experienced concurrently, and stakeholders may even be co-producers or co-creators of services. Thus, issues may arise in the co-production process, and the organisation’s ability and approach to managing such issues become a critical factor that determines its reputation.

Furthermore, this study’s outcome illustrates the benefits of deriving more context-specific measures particularly when using a cognitive approach. Most of the dimensions derived from stakeholders in the study context were more cognitive than emotional dimensions. Although a ‘seemingly’ emotional measure, ‘trustworthiness’ emerged as one of the six reputation dimensions in this study, the items that were retained after conducting the factor analysis do not illustrate the conventional emotional measure seen in reputation studies. Although it is important to point out that prior to the conducting the EFA, “It is important that I trust the organisation” was one of the underlying items for the ‘trustworthiness’ dimension. However, the item did not meet the acceptable factor loading and was, therefore, eliminated. Hence, for banks and MSPs, stakeholders’ trust in the organisation is determined by rational factors and not by merely liking the organisation. Stakeholders must be convinced that the organisation is transparent in its activities and has no hidden charges before they can trust it.

Consequently, stakeholders’ assessments of the service organisations in the study context are mainly based on the ‘facts’ – what they see, hear and know of the activities of the organisations. This, however, does not undermine the relevance of the ‘emotional appeal’ dimension as two out of the six items underlying the dimension were considered relevant by stakeholders and were retained after conducting the EFA but did not make the top six reputation dimensions for service organisations in this study. Service organisations must, therefore, focus more on investing in the cognitive aspects of their operations because they have the most influence on stakeholders’ favourable assessments.

Besides, the fact that stakeholders would consider dimensions like regulatory compliance, and trustworthiness before the dimension of service quality in a service sector like bank indicates that service organisations cannot merely rely on the service offering to be truly reputable. The finding supports studies and scholars (Mmutle and Shonhe 2017; Steyn and De Beer 2012; Smith et al. 2013; Kitchen and Laurence 2003) that concluded that stakeholders’ expectation of organisations has shifted from mere production of goods and services to other areas of the organisation’s activities such as its communication with stakeholders, the corporate citizenship, contribution to society etc. It is, therefore, not surprising that ‘corporate communication’ and ‘social responsibility’ emerged as the third and fourth most significant reputation dimensions for service organisations.

The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on corporate reputation and overall corporate performance is particularly emphasised in the literature, and it is undoubtedly one of the primary aspects of organisations that must be prioritised and effectively implemented. A recent study by cf. Ajayi and Mmutle (2021) pointed out that of the seven reputation dimensions contained in the RepTrak instrument, a 2018 reputation survey found that all three dimensions that address the CSR aspect of business ranked in the top 4 most important dimensions that drive the reputation of organisations operating within the South African business context. That is, the dimensions ‘governance’, ‘performance’ and ‘citizenship’, respectively, emerged as the 2nd, 3rd and 4th most important dimensions. Their study further highlighted that ‘governance’ was the most important driver of reputation in several sectors, which included the banking sector, while the ‘citizenship’ and ‘performance’ dimensions varied between the second and fourth most important drivers in the telecommunication and banking sectors. The outcome of the survey clearly strengthens and supports the fact that stakeholders are increasingly interested in various aspects of an organisation and in the business environment today, mere production of goods or services is no longer enough to be truly reputable.

Conclusion

More than ever before, having context-specific reputation measures is crucial in order to have more accurate measures of corporate reputation since organisations do not achieve a good reputation only on the basis of good service provision, but on how stakeholders assess its efforts in meeting their other expectations. Unfortunately, there has been a dearth of studies on what constitutes these stakeholders’ expectations particularly in service organisations, and in developing markets. This study is an effort to fill this void and contribute to literature on corporate reputation measurements in emerging economies.

The study show how context-specific reputation measure can be, therefore, using dimensions derived in one context as a measure of corporate reputation in another context may produce inaccurate results. As it is apparent from the outcome of this study, none of the existing measurement instruments are on their own, an accurate reflection of the dimensions considered by stakeholders in the study context. Thus, the study outcome makes a notable scholarly contribution towards the reputation measures of banks and mobile service providers particularly in a developing country context. It identifies dimensions and measurement items not used in other measures, a finding which may be useful to others.

As this study used only two service organisations, it is highly unlikely that the findings can be generalised to all kinds of service organisations. We conclude that banks and mobile service providers organisations in a developing country context may, therefore, measure their reputation along 6 dimensions namely: issue management, service quality, corporate communication, branding, social responsibility, and trustworthiness. From a managerial perspective, these organisations place these six dimensions at the top of corporate agendas.

That is, managers of the sampled organisations must ensure that stakeholders rate them high on each dimension. Specifically, managers must ensure that online platforms are available for stakeholders to reach the organisation when necessary. The organisations’ online platforms particularly make a significant impact on stakeholders’ assessment of the corporate reputation because in today’s digital era, stakeholders do not expect to be physically present at an organisation before they can make a purchase, transact or resolve issues. More so, because the two service organisations used for this study are ‘daily need’ organisations, the presence of information and communication technologies (ICT) save stakeholders, especially customers, unnecessary trips to the organisations and this ‘convenience’ contributes to their favourable perception of the organisation.

It is expected that implementing the six reputation dimensions will enable organisations to align their activities with stakeholders’ expectations and ultimately boost the corporate reputation.

Recommendation for further research

Although this study makes significant contribution by identifying dimensions not evident in existing reputation measures, the dimensions were not subjected to a re-test. Subsequent studies looking to apply these reputation dimensions to other contexts must, therefore, subject the dimensions to a re-test to confirm their suitability.

Also, subsequent research should consider using a larger sample size. While the sample size used in this study is considered significant and adequate for the investigation, future research should use a larger sample in order to have a more robust outcome.

References

Adeosun, L., and R. Ganiyu. 2013. Corporate reputation as a strategic asset. International Journal of Business and Social Science 4 (1): 220–225.

Akintade, A. 2019. Mr Biggs: The Rise and Fall of Popular Nigerian Eatery. https://www.herald.ng/mr-biggs-rise-fall-popular-nigerian-eatery/ (Accessed March 12, 2019).

Ajayi, O.A., and T. Mmutle. 2021. Corporate reputation through strategic communication of corporate social responsibility. Corporate Communications 26 (5): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-02-2020-0047.

Apéria, T., P.S. Brønn, and M. Schultz. 2004. A reputation analysis of the most visible companies in the Scandinavian countries. Corporate Reputation Review 7 (3): 218–230.

Awang, Z.H., and K. Jusoff. 2009. The effects of corporate reputation on the competitiveness of Malaysian telecommunication service providers. Internal Journal of Business and Management 4 (5): 173–178.

Balan, D.A., and A. Schiopoiu. 2017. The development of a corporate reputation metric: A customer perspective. In Major challenges of today’s economy, ed. F. Pînzaru, et al., 595–606. Bucharest: Tritonic.

Balmer, J.M.T., and S.A. Greyser. 2006. Integrating corporate identity, corporate branding, corporate communications, corporate image and corporate reputation. European Journal of Marketing 40 (7/8): 730–741.

Benson, E.A. 2019. Stakeholders are Displeased with MTN over Constant Infractions. https://nairametrics.com/2018/09/20/stakeholders-are-displeased-with-mtn-over-constant-infractions/. (Accessed March 11, 2019).

Bergh, D.D., D.J. Ketchen Jr., B.K. Boyd, and J. Bergh. 2010. New frontiers of the reputation performance relationship: Insights from multiple theories. Journal of Management 36 (3): 620–632.

Bolarinwa, O.A. 2015. Principles and methods of validity and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social and health science researches. Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal 22: 195–201.

Carreras, E., A. Alloza, and A. Carreras. 2013. Corporate reputation. London: Lid Publishing.

Caruana, A., and S. Chircop. 2000. Measuring corporate reputation: A case example. Corporate Reputation Review 3 (1): 43–57.

Carroll, C.E. 2016. Reputation, dimensions of. In the Sage encyclopedia of corporate reputation, ed. C.E. Carroll, 616–623. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Chun, R. 2005. Corporate reputation: Meaning and measurement. International Journal of Management Review 7 (2): 91–109.

Chun, R., and G. Davies. 2006. The influence of corporate character on customers and employees: Exploring similarities and differences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34 (2): 138–146.

Cooper, D.R., and P.S. Schindler. 2007. Business research methods, 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Creswell, J.W. 2014. Research design: Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Davies, G., J.I. Rojas-Méndez, S. Whelan, M. Mete, and T. Loo. 2018. Brand personality: Theory and dimensionality. Journal of Product & Brand Management 27 (2): 115–127.

Davies, G. 2011. The meaning and measurement of corporate reputation. In corporate reputation, ed. R.J. Burke, et al., 45–60. Surrey, England: Gower.

Dowling, G.R., and N.A. Gardberg. 2012. Keeping score: The challenges of measuring corporate reputation. In Oxford handbook of corporate reputation, ed. M.L. Barnett and T.G. Pollock, 34–68. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fakoyejo, O. 2019. 33-years After, Mr. Bigg’s is Not so Big Anymore. https://nairametrics.com/2019/07/18/33-years-after-mr-biggs-is-not-so-big-anymore/ (Accessed March 12, 2019).

Feldman, P., R. Bahamonde, and I. Bellido. 2014. A new approach for measuring corporate reputation. International Journal of Business and Management Review 7 (16): 53–66.

Gardberg, N., and C. Fombrun. 2002. The global reputation quotient project: First steps towards a cross-nationally valid measure of corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review 4 (4): 303–307.

Global RepTrak 100. 2013. The world's most reputable companies in 2013. Reputation Intelligence Special issue: 3–18.

Hair, J.F., W.C. Black, B. Babin, and R.E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Izquierdo, I., J. Olea, and F.J. Abad. 2014. Exploratory factor analysis in validation studies: Uses and recommendations. Psicothema 26 (3): 395–400.

Kanto, D., E. Run, and A. Isa. 2015. The reputation quotient as a corporate reputation measurement in the Malaysian banking industry: A confirmatory factor analysis. Social and Behavioral Science 219: 409–415.

Kitchen, P.J., and A. Laurence. 2003. Corporate reputation: An eight-country analysis. Corporate Reputation Review 6 (2): 103–117.

Kyriazos, T. 2018. Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology 9: 2207–2230.

Mmutle, T., and L. Shonhe. 2017. Customers’ perception of service quality and its impact on reputation in the hospitality industry. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 6 (3): 1–25.

Mohajan, H. 2017. Two Criteria for Good Measurements in Research: Validity and Reliability. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/83458/ (Accessed July 4, 2019).

Money, K., and C. Hillenbrand. 2006. Using reputation measurement to create value: An analysis and integration of existing measures. Journal of General Management 32 (1): 1–12.

NairaMetrics, (2018). Why GLO and 9mobile are Losing Their Internet Mobile Subscribers. https://nairametrics.com/2018/06/05/glo-and-9mobile-loses-mobile-subscribers-in-april-2018/ (Accessed March 12, 2019).

Olmedo-Cifuentes, I. and I.M Martínez-León. 2011. Medida de la reputacio´n empresarial en pymes de Servicios. Revista Europea de Direccio´n y Economı´a de la Empresa 20(3): 77–102.

Olmedo-Cifuentes, I., I.M. Martínez-León, and G. Davies. 2014. Managing internal stakeholders’ views of corporate reputation. Service Business 8 (1): 83–111.

Ponzi, L., C. Fombrun, and N. Gardberg. 2011. RepTrak pulse: Conceptualizing and validating a short-form measure of corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review 14 (1): 15–35.

Pulse NG. 2019. A New Moody's Report Reveals Exactly How Diamond Bank failed. https://www.pulse.ng/bi/finance/a-new-moodys-report-reveals-exactly-how-diamond-bank-failed/t6tqb6x#:~:text=The%20bank's%20leadership%20made%20several,in%20former%20CEO%20Uzoma%20Dozie (Accessed March 11, 2019).

Shamma, H., and S. Hassan. 2009. Customer and non-customer perspectives for examining corporate reputation. Journal of Product and Brand Management 18 (5): 326–337.

Smith, A., W. Rupp, and W. Motley. 2013. Corporate reputation as strategic competitive advantage of manufacturing and service-based firms: Multi-industry case study. International Journal of Services and Operations Management 14 (2): 131–155.

Soleimani, M.A., W.D. Schneper, and W. Newberry. 2014. The impact of stakeholder power on corporate reputation: A cross-country corporate governance perspective. Organization Science 25 (4): 991–1008.

South Africa RepTrakTM Pulse. 2013. 2013 Reputation Survey. https://www.fin24.com/Companies/ICT/Vodacom-tops-reputation-survey-20130424 (Accessed 4 July 2019).

Steyn, B., and E. De Beer. 2012. Conceptualising strategic communication management (SCM) in the context of governance and stakeholder inclusiveness. Communicare 31 (2): 29–55.

Taber, K. 2018. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education 48 (6): 1273–1296.

The Guardian. 2018. How Intrigues, Lapses, Losses Caused Diamond Bank’s fall. https://guardian.ng/business-services/how-intrigues-lapses-losses-caused-diamond-banks-fall/ (Accessed March 12, 2019).

Trotta, A., and G. Cavallaro. 2012. Measuring corporate reputation: A framework for Italian banks. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies 4 (2): 21–31.

Wang, Y., H. Lo, and Y.V. Hui. 2003. The antecedents of service quality and product quality and their influence on bank reputation: Evidence from the banking industry in China. Managing Service Quality An International Journal 13 (1): 72–83.

Wartick, S.L. 2002. Measuring corporate reputation. Definition and data. Business & Society 41 (4): 371–392.

Wepener, M., and C. Boshoff. 2015. An instrument to measure the customer-based corporate reputation of large service organizations. Journal of Services Marketing 29 (3): 163–172.

Yasin, B. and Z. Bozbay. 2011. The impact of corporate reputation on customer trust In 16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications, 505–518.

Zeithaml, V.A., M.J. Bitner, and D.D. Gremler. 2009. Services marketing, 5th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all participating authors, no conflict of interest is to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ajayi, O.A., Mmutle, T. & Chaka, M. A Stakeholders’ Perspective of Reputation Dimensions for Service Organisations: Evidence from a Developing Country Context. Corp Reputation Rev 25, 287–299 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-021-00128-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-021-00128-2