Abstract

Purpose

Despite recent advances in cancer control and the number of cancer survivors increasing substantially over the past years, some cancer survivors continue to experience disparities due to barriers to recommended survivorship care. The use of survivorship care plans (SCPs) may be a way to help care for these individuals and their respective issues after they complete their primary treatment. The purpose of this scoping review is to understand the evidence on SCPs among minority, rural, and low-income populations: groups that experience disproportionately poorer cancer health outcomes.

Methods

Computer-based searches were conducted in four academic databases. We included peer-reviewed studies published in the English language and conducted in the USA. We systematically extracted information from each paper meeting our inclusion criteria.

Results

Our search identified 45 articles. The 4 major themes identified were (1) disparities in the receipt of SCPs where populations experience unmet needs; (2) benefits of SCPs, including improved care coordination and self-management of cancer; (3) needs and preferences for survivorship care; and (4) barriers and facilitators to using SCPs.

Conclusions

Despite the potential benefits, underserved cancer survivors experience disparities in the receipt of SCPs and continue to have unmet needs in their survivorship care. Survivorship care may benefit from a risk-stratified approach where SCPs are prioritized to survivors belonging to high-risk groups.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

SCPs are a tool to deliver quality care for cancer survivors. While evidence is mixed on SCPs’ benefits among the general population, SCPs show promise for underserved populations when it comes to proximal outcomes that contribute to disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem in the USA with more than 1.9 million new cases of cancer expected to be diagnosed in 2023 [1]. It is estimated that approximately 18 million individuals with a history of cancer were alive in the USA in January 2022 [2]. Importantly, this number is expected to increase to more than 22.1 million individuals by January 2030 [3]. Due to recent advancements in early detection and treatment, many adult cancer survivors can expect to live for decades; however, optimal cancer care is not universally available and can result in disparities for medically underserved populations [4, 5]. Medically underserved populations are described as groups of people with cultural or economic barriers hindering them from receiving adequate medical care services [6]. These groups can include different racial and ethnic minorities, those with lower socioeconomic status (SES), and those living in rural geographic areas who have disproportionate cancer burdens when compared to people who have more access to better quality of care [7]. Populations that experience barriers to receiving high-quality cancer treatment may also experience disparities in survivorship care and survivorship experiences [8, 9]. This creates the need for effective survivorship care among these vulnerable populations of cancer survivors to manage the impact of their cancer treatment.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) highlighted the growing concerns surrounding the lack of clarity of what to expect after treatment by both patients and providers [10]. There are many health effects that are associated with a cancer diagnosis [2, 11] such as mental health issues, long-term or late effects, stress, and the recurrence of cancers [12,13,14]. Importantly, survivorship care following treatment should be patient-centered and tailored to the unique needs, experiences, and challenges of each patient [15]. One way to help care for these individuals and their respective issues is the use of survivorship care plans (SCPs) [10]. These detailed plans provided to patients after they complete their primary treatment contain a summary of their cancer treatment and recommendations for follow-up care. The IOM identified survivorship care planning as a key component in ensuring quality care for cancer survivors [10]. As a result, several leading organizations embraced this recommendation, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), a leader in creating templates which were mandated through the American College of Surgeon’s Commission on Cancer (CoC). SCPs are individualized guidelines detailing how to properly take care of, monitor, and maintain a cancer survivor’s health [11]. They include treatment summaries, upcoming surveillance/follow-up visits, other cancer screenings, and healthy behaviors to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and/or secondary cancer. While existing research provides little evidence that SCPs improve health outcomes and healthcare delivery, findings are more positive for proximal outcomes such as information received and care delivery, particularly when SCPs are accompanied by counseling to prepare cancer survivors for future clinical encounters [16]. Furthermore, while cancer survivors show satisfaction with SCPs [17], they still experience unmet needs post-treatment which could result from resource barriers hindering their proper implementation [17].

Recent attention has been given to potential disparities in cancer survivorship outcomes among groups that are underserved. For example, rural and low-income survivors experience gaps in supportive care during and after the completion of treatment [18]. In addition, a previous review examining the use of SCPs among racial and ethnic minority female breast cancer survivors found that receiving SCPs was desired by this population but given sporadically [19]. Although studies explored the use of SCPs among other groups that are underserved such as those living in rural or remote areas or low-income populations, these studies were not systematically reviewed and synthesized to date. The objective of this study is to conduct a scoping review to understand the evidence on SCPs among various underserved populations.

Methods

For this study, we followed the scoping review methodology proposed by Arksey and O’Malley which informed the following steps: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) data charting, and (5) collating and reporting results [20]. We chose this methodology given that scoping reviews are often used to map a body of literature on a topic and identify knowledge gaps [21]. We present steps 1 through 5 of our scoping review below.

Step 1: Identifying the research question

The main research question guiding our review was: “What is the evidence on survivorship care plans among underserved populations?” Our scoping review aimed to analyze and synthesize the available evidence on SCPs among minority, rural, and low-income populations. This review will contribute to further cancer SCP development by addressing the following issues: (1) understanding the use of SCPs among groups that are underserved, (2) identifying the barriers that healthcare organizations face when trying to implement plans into their post-treatment care and tailor them to groups that are underserved, and (3) providing insights for future research directions.

Step 2: Identifying relevant studies

Search strategy

Our study followed the recommendations of the statements on Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [22, 23]. Web-based searches were conducted in the following academic databases: (1) PubMed (cancer subset), (2) MEDLINE, (3) PsycINFO, and (4) CINAHL. To optimize the search results, we used various combinations of keywords taken from the existing literature and Medical Subject Headings terms (see Appendix 1). Lastly, we identified additional studies using a snowball searching technique where we examined the reference lists of all included studies that met our inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

We identified papers that appeared in peer-reviewed journals and were published in the English language from January 2005 through December 2023. We limited our search to studies published after 2005, the year the seminal IOM report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, was published highlighting the need for effective survivorship care [10]. Like other reviews focused on groups that are underserved, we limited eligible articles to those published in English, from studies conducted in the USA [24]. Studies were included if they focused on SCPs in the following underserved groups: racial and ethnic minorities, low SES populations, and rural populations. Underserved populations had to make up at least 30% of study participants. Studies that did not focus on these underserved groups but conducted sub-group analyses to identify factors related to these populations and present findings specific to the included underserved groups were also eligible. For such studies, we lowered our threshold to 20% study participants representing underserved groups. Studies also had to present results on these groups separately and not as part of the overall sample. However, during full-text review, we made an exception for studies using nationally representative datasets such as BRFSS. Even though all findings were not reported separately for some studies, these studies provided important evidence on SCPs.

Step 3: Study selection

Each study was individually assessed for relevance. Any disagreements between reviewers were reconciled by consensus. We used a two-step inclusion process to identify articles that met our inclusion criteria. In step 1, we examined paper titles and abstracts and excluded studies that clearly did not have a focus on either SCPs or cancer or groups that are underserved. Each citation was independently reviewed by all reviewers (WLT, PJ, SR, and AP). Disagreements between reviewers were reconciled by consensus. In step 2, the full-text papers of the remaining citations were obtained for independent assessment of all inclusion criteria.

Step 4: Data charting

Data extraction was done in duplicate by WLT and PJ, independently. As in step 1, any disagreements were reconciled by consensus. We systematically extracted the following information from each of the papers included in our review: the populations of interest (African Americans, Hispanics, low-income populations, rural, etc.), the cancer type (breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, etc.), study design (cohort study, randomized controlled trial, etc.), details about the SCPs (paper or electronic), and whether there was any evidence of tailoring of the SCPs.

Step 5: Collating and reporting results

Using the information from the data extraction, we created descriptive and numerical summaries of the information from published studies related to our scoping review objectives. Details related to SCP and SCP components, factors that influenced their use and effectiveness, were extracted and synthesized. Within results and discussions, we identified themes and sub-themes. We conducted a qualitative thematic analysis and grouped findings into four major themes derived from their meaning. This process was conducted through a series of discussions among the authors until a consensus was reached.

Results

Included studies

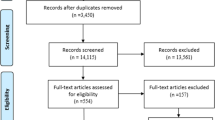

Our keyword search identified an initial yield of 2438 unique articles. Studies in step 1 were most frequently excluded for not having a focus on cancer or SCPs, being conducted outside of the USA, and not targeting a group that is underserved (see Fig. 1). After excluding these citations, 295 articles were included in step 2. The primary reasons for exclusion at this stage included not having a focus on cancer or SCPs and being conducted outside of the USA. After applying all the exclusion criteria in the review of full-text articles, 42 studies were included. The snowball search yielded an additional 3 articles. Data was extracted from the final set of articles. A total of 45 studies were included in this systematic review published between 2009 and 2023 (see Appendix 2 for a list of included studies).

Study characteristics

Twenty-three of the included studies used quantitative methods, 14 used qualitative methods, and 8 used mixed methods. Most quantitative studies (16/23) were cross-sectional studies, 2 were cohort studies, 4 were randomized control trials (RCTs), and 1 was a single-arm study. Six of the 14 qualitative studies used focus group discussions, 4 used semi-structured interviews, 3 used community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches (consensus meetings, focus groups, interviews), and 1 was a think aloud. Studies varied with respect to the population targeted, type of SCPs administered (treatment summary or follow-up care plan), and the cancer type of interest. The majority of studies focused on Black populations followed by studies targeting diverse populations of more than one group that is underserved. In addition, most studies focused on breast cancer (n = 29) survivors, followed by colorectal (n = 11), gynecologic (n = 11), and prostate cancer (n = 10) survivors.

Theme 1: Benefits of survivorship care plans

One recurring theme we identified was related to benefits from SCPs in 18 articles (see Table 1). Eleven studies were quantitative composed of 3 RCTs, 1 single-arm trial, 6 cross-sectional studies, and 1 cohort study. Four were qualitative composed of 2 CBPR (focus groups, RAND-Delphi method, and interviews), 1 focus group study, and 1 think aloud. Two of the 3 mixed methods studies were single-arm studies, 1 was an RCT, and all 3 used semi-structured interviews. Participants including both healthcare providers and survivors across different studies found the SCP to be useful [25, 26]. Some articles studied the effects of SCP interventions that entailed some form of patient navigation through counseling with nurses or nutritionists [27,28,29]. For example, Maly and colleagues conducted an RCT of SCPs for a low-income, predominantly Latina population of breast cancer survivors [29]. This study examined the effects of treatment summaries and SCPs coupled with a nurse counseling session on physician implementation of survivorship care. Participants in the intervention group reported greater physician implementation of survivorship care such as treatment of hot flashes. Herschman and colleagues conducted an RCT among women with early-stage breast cancer [28]. Participants in the intervention group met with a nurse/nutritionist who provided them with a treatment summary, surveillance, and lifestyle recommendations. This study found no significant improvements in patient-reported outcomes like treatment satisfaction, survivor concerns, depression, and impact of cancer; however, the intervention was associated with decreased worry in the short term. In a separate publication, this group also found that the intervention was effective at changing behaviors and improving knowledge in the short term and was less effective among Hispanic people in improving attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity when compared with non-Hispanic White individuals [27].

In place of clinic-based interventions, Casillas and colleagues developed and tested a culturally tailored intervention that included family members of Latino adolescent and young adult survivors and a community health advocate. This intervention resulted in increased knowledge and confidence in the management of survivorship care for both survivors and family members [30]. In another study, Nápoles and colleagues combined a culturally tailored paper SCP, Spanish language mobile health (mHealth) app, and telephone coaching to address survivorship care in Spanish-speaking Latina breast cancer survivors [31]. This intervention reduced fatigue and distress among survivors, increased knowledge of care resources, increased physical activity, improved general well-being, and provided a sense of accountability and motivation through feedback from the telephone coaching and mHealth app [31]. Baseman and colleagues explored the acceptability and feasibility of an SCP in the form of an mHealth app for rural survivors [32]. Both survivors and their providers noted greater self-efficacy and communication on account of the journaling and reports features. Participants in this study also reported that the reminders feature was useful for surveillance [32].

In a survey study of rural cancer survivors, Lewis-Thames and colleagues found that rural survivors receiving written post-treatment survivorship communication had greater odds of reporting timely follow-up care [33]. In an evaluation of a structured care plan called Care Sequence in five safety-net institutions and five non-safety-net institutions, the SCP was perceived as useful [26]. Patient self-management metrics like clarity on the timing and sequence of care, as well as care delivery metrics like flu vaccinations, were higher in those who received Care Sequence. These benefits were similar for both safety-net and non-safety-net survivors. Survivors also cited benefits like having structure to stay focused on the task, and ability to see a timeline, and proactively seeking answers [26]. Similar benefits were mentioned by healthcare providers and survivors in the qualitative study by Ko and colleagues which found the SCPs helped patients become proactive about their care and formulate questions for their healthcare visits [34].

Theme 2: Receipt of survivorship care plans

Sixteen studies brought attention to cancer survivors and their likelihood of receiving an SCP (see Table 2). A majority of these studies were quantitative using cross-sectional designs (n = 13) with two studies using qualitative methods in the form of focus groups (n = 1) and semi-structured interviews (n = 1). Lastly, one study used both a cross-sectional design as well as semi-structured interviews (n = 1). Using a sample of cancer survivors from the LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center of Excellence Network sites, Casillas and colleagues used survey data and found that minority cancer survivors were significantly less likely to have an SCP [35]. In addition, minority cancer survivors had higher odds of reporting low confidence in managing their cancer survivorship care [35].

Several cross-sectional studies using Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data also showed that cancer survivors with lower education [36,37,38,39] and income [36,37,38,39] and being uninsured [39] were less likely to report receiving SCPs. For example, Jabson and colleagues found that demographic characteristics were associated with the receipt of treatment summaries and follow-up care instructions [37]. More specifically, cancer survivors who reported completing less than a high school education and who reported household incomes lower than $50,000 had lower odds of reporting receipt of treatment summaries. Incidentally, this study also found that Hispanic cancer survivors were more likely to receive treatment summaries [37]. Wu and colleagues used BRFSS data and found that low-income breast cancer patients had lower odds of receiving follow-up care instructions from their providers [40].

Sabatino and colleagues examined the receipt of treatment summaries and follow-up instructions among African-American and Hispanic cancer survivors [41]. This study found that many recently diagnosed cancer survivors did not report receiving treatment summaries and written follow-up instructions. In addition, race and ethnicity were associated with lower reporting of summaries. DeGuzman and colleagues explored the needs of a sample of seven rural, low-income breast cancer survivors and their post-treatment survivorship care planning [18]. This study found that rural survivors had a lack of knowledge of post-treatment care, such as how to assess cancer recurrence. In addition, none of the women reported receiving or hearing about an SCP. While some women reported receiving a packet of information, there was no specific information provided.

Tawfik and colleagues implemented and evaluated a process of generating and delivering SCPs to patients and providers in a comprehensive cancer center that serves poor, rural, and minority cancer patients [42]. They reported that of all the SCPs ordered, about 85% were generated, and of those generated about a third (34.2%) were given to patients. Approximately half (48.9%) of SCPs were sent to primary care providers (PCP) by mail or fax, and 8.3% of these were received [42].

Theme 3: Needs and preferences of survivors

A third major theme was related to identifying the unmet needs and preferences of groups that are underserved with respect to the contents of SCPs. We identified 18 studies targeting Black, Latina, rural, and low-income cancer survivors (see Table 3). These studies were predominantly qualitative (n = 12) followed by 5 mixed-methods studies and 1 quantitative study. Most studies used focus groups (n = 5) or semi-structured interviews (n = 3). Others included CBPR (consensus meetings, focus groups, interviews, RAND-Delphi methods) (n = 3) and a think aloud study (n = 1). The mixed method studies were cross-sectional (n = 3) or single-arm trials (n = 2), and most used semi-structured interviews as well (n = 4).

Content

In a qualitative study seeking to understand if SCPs are responsive to the needs of Black breast cancer survivors, Ashing-Giwa and colleagues found that while Black cancer survivors felt they would benefit from a well-organized SCP, they found several limitations to the SCP including inadequate information related to health history, the number and severity of comorbidities, health promotion, referrals to other specialists, and functioning [43]. Similar findings were presented in other qualitative studies [44, 45]. Burke and colleagues found that racial and ethnic minority women suggested that the SCP should include referrals to PCPs who were knowledgeable about their cancer and associated side effects. Women in this study also hoped the SCP would provide them with questions to ask their PCP [45].

The preferences for content differed based on the survivor or provider perspective. For example, minority cancer survivors noted wanting more information on lifestyle management, like physical activity and nutrition [43,44,45,46], whereas providers noted this type of content was less useful [47]. However, both groups agreed that information on genetic testing was an important addition [43, 45, 47]. Other needs expressed by Black survivors included referrals to spiritual care and culturally competent providers [43].

Tisnado and colleagues found numerous gaps and unmet needs among a sample of Latina breast cancer survivors [48]. While few women in this sample reported receiving an SCP, those who did receive an SCP were treated at a high-resource cancer center. In addition, participants also reported unmet needs in their survivorship care related to finances, continuity of care, and a lack of information related to symptom management.

Studies also assessed perspectives on the different components of SCPs. Preferred SCP elements included graphical representation of timing and sequence of care [26] and visual and auditory feedback from SCPs embedded in apps [31].

Format

In terms of format, survivors differed in their preference for paper versus electronic SCPs. Hispanic breast cancer survivors preferred a print SCP [34, 46]. Conversely, rural participants in the study by Baseman and colleagues, which examined the feasibility and acceptability of SCP as an mHealth app, reported they did not want print SCPs [32]. In addition, rural PCPs preferred an electronic SCP that could be pushed from the oncologists’ electronic health record (EHR) to theirs [47].

Other format suggestions included the use of images [32, 46], improved readability [32, 44, 46], and tailoring for cultural appropriateness [43, 46]. Several preferences for layout were articulated across these studies: having key information on one sheet [26] and providing space for Black survivors to make notes [43].

Facilitating conditions

In addition to content, format, and layout, survivors mentioned other factors that would facilitate the use of SCPs.

SCP aids

For example, Hispanic survivors identified SCP aids in the form of patient navigators or coaches [31, 49]. Black survivors believed the information shared within SCPs should be discussed with their healthcare providers [44]. Studies also found that Hispanic patients also preferred aids like animated videos [34] or photonovelas [30] to provide SCP information.

Findings based on survivor perspectives suggest that discussing SCPs with the provider, and the timing when this discussion occurs, may be associated with the implementation of SCPs. Burke and colleagues reported that in-person review of SCPs, and delivery of SCPs at transition points in the cancer journey such as during active treatment, between active treatment and survivorship may facilitate the use of SCPs [45]. However, DeGuzman and colleagues reported that discussing SCPs in the final treatment appointment hindered knowledge retention by survivors [18].

Language

In a project aiming to translate and tailor the ASCO breast cancer treatment summary template to Latino breast cancer patients, the translated version was found to be more favorable than the ASCO template with respect to content, clarity, utility, cultural and linguistic responsiveness, and socioecological responsiveness [46]. Participants also liked that the template was bilingual, providing English text with Spanish translations adjacent to each other.

Coordination

Both survivors and providers noted that the transition from cancer care to primary care was poor [47]. Survivors suggested that SCPs include referrals to PCPs knowledgeable about cancer side effects [45].

Theme 4: Barriers and facilitators to implementation of survivorship care plans

Lastly, we identified 19 studies related to barriers and facilitators of implementing SCPs predominantly based on healthcare provider perceptions (see Table 4). Seven of these studies were qualitative, 4 were quantitative, and 8 used mixed methods. The qualitative studies used semi-structured interviews (n = 3), focus groups (n = 2), CBPR (consensus meetings) (n = 1), and think aloud approaches (n = 1). Half of the quantitative studies were cross-sectional (n = 2), and the rest were a cohort study (n = 1) and an RCT (n = 1). Of the 8 studies using mixed methods, 3 were cross-sectional, 1 was an RCT, 3 were single-arm studies, and 1 carried out a suitability of materials assessment. The qualitative components included semi-structured interviews (n = 5), focus groups (n = 1,) and CBPR (consensus meetings) (n = 1). This theme is further divided into 4 categories.

Design-related factors

Lyson and colleagues found that none of the SCPs from 53 health systems caring for vulnerable populations was concordant with IOM recommendations for SCPs [50]. In addition, designing SCPs with input from diverse populations and tailoring SCPs for readability and cultural appropriateness could facilitate the implementation of SCPs [32, 45, 50]. However, cost in terms of staff time and resources posed a barrier to developing understandable and comprehensive SCPs [50, 51].

In 2 of the 19 studies, SCPs were re-engineered with input from healthcare providers caring for groups that were underserved. Among providers in a rural research network, design features that facilitated the use of SCPs included modifications like the addition of a date field to determine the outdatedness of contents, clearly labeling the cancer diagnosis as early as possible, focusing on follow-up care rather than treatment summaries, and removing screening recommendations that were not cancer-related [47]. Further, providers indicated a preference for having a single SCP for patients and themselves. In a study among providers, participants found SCPs to be too long [52]. Yet, they did not recommend the removal of any sections; instead, they recommended bulleted lists or summaries at the beginning of the SCP and suggested having separate SCPs for patients and providers [52].

Provider preferences for layout were predominantly based on a study of PCPs, who suggested labeling the sections on an electronic SCP, the addition of a date-created field for easier navigation, labeling cancer diagnosis clearly, direct links from treatment information to supporting documents [47], and a reminder function for appointments [32].

Organizational factors

Healthcare providers noted the lack of coordination between primary care and oncology as a barrier to the use of SCPs [25, 42, 53]. Primary care providers in a rural primary care practice reported either rarely or never receiving SCPs from oncology providers, did not have a formal process to identify cancer survivors, and were unaware of how to access resources for cancer survivors [53]. In a study based in a comprehensive cancer center treating poor, rural, and minority survivors, PCPs reported a low receipt of SCPs from oncologists sent via mail or fax [42]. Suggestions to facilitate the use of SCPs included one to two pages of specific recommendations from oncologists [53], periodic updates by oncologists [25], and health systems using a standard SCP to share with PCPs [51]. Isaacson and colleagues noted an organizational barrier in assessing the use of SCPs for survivors treated by providers, whose only affiliation with health systems may be for the purpose of using surgical facilities [51].

Technology-supported SCPs

Two studies focused on mHealth approaches to implementing SCPs. Based on an RCT of an SCP embedded in an mHealth app among racial and ethnic minorities, Psihogios and colleagues found that trivia questions and health goal messages increased engagement with the app, and this engagement varied by the season when messages were sent [54]. Baseman and colleagues explored the feasibility and acceptability of a mobile breast cancer survivorship care app among six rural breast cancer survivors, four PCPs, and one oncologist [32]. Survivors in this sample were enthusiastic about having one location for all information such as contact information, their treatment records, insurance numbers, and other relevant information. All survivors perceived their existing ways of self-management, surveillance, and monitoring as inadequate. The tool was seen as a better way to self-manage their survivorship and track symptoms, wellness activities, and mood. Portability was also seen as a plus as they always had their mobile phones available. Providers identified interoperability with other healthcare systems as a potential barrier, expressing concerns about data quality if the system relied on manual data entry [32].

Technology-related barriers

Isaacson and colleagues also highlighted implementation issues within two large rural health systems [51]. Operability was identified as a challenge within both institutions. Within one healthcare system, inefficiencies were identified within the ASCO template which could require multiple deletion of items unrelated to a patient’s treatment and survivorship. They used their Microsoft Word-friendly EHR system to prepare individualized SCPs. Whereas the other healthcare system integrated the SCP templates into their EHR that would populate the already existing data [51]. Multiple studies reported challenges with EHR integration [47, 52, 53], while Klemp et al. specifically reported difficulties in locating an SCP in the EHR [53].

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to review the current evidence on the use of SCPs among groups that are underserved. We included 45 studies targeting various populations including racial and ethnic minorities (e.g., Blacks and Hispanics), low-income, and rural populations. Based on this review, we identified four overarching themes with respect to the implementation of SCPs among these populations. First, groups that are underserved report the benefits of using SCPs. Second, despite acknowledging benefits, these groups also report lower rates of receiving SCPs compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts. Third, there are substantial unmet information needs, as well as preferences, within this population that are not being addressed. Fourth, tailoring SCPs to target populations, addressing organizational barriers to disseminating SCPs, and electronic mode of delivery may improve knowledge retention and acceptability of these tools among survivors and their providers.

Benefits of SCPs exist among underserved populations

Our review found several benefits of SCPs, including improved care coordination (e.g., timely follow and adherence to care) and self-management of cancer. These findings align with those of Lewis-Thames and colleagues, who found benefits such as improving disease management and aiding patient-provider communication and care coordination among minority breast cancer survivors [19]. In addition, reviews among the general population of cancer survivors also found positive findings for proximal outcomes such as adherence to care for patients [16] and care coordination for providers [16, 55]. However, much of the attention in the field has focused on the mixed evidence associated with the impact of SCPs on more distal outcomes such as health outcomes [16, 17]. However, it should be noted that underserved populations may be underrepresented in this research. When populations are pooled together, interesting and unique differences may be washed out. In addition, underserved populations may benefit more from improvements in these proximal outcomes which are contributors to health disparities which could ultimately lead to improvements in health outcomes and health equity among these populations.

Disparities in receipt of SCPs further limit their benefits

While there are potential benefits to the use of SCPs among underserved populations, these benefits cannot be fully realized due to disparities in the receipt of SCPs. Our study found that groups that are underserved reported lower rates of receiving treatment summaries, follow-up care instructions, and survivorship self-care. Previous studies have also reported on the lack of adoption of SCPs [56, 57]. Several barriers exist when it comes to adopting and implementing SCPs including the lack of reimbursement for preparing SCPs, as well as the lack of time and resources. These barriers may be more pronounced among providers predominantly serving racial and ethnic minority populations, rural populations, and low-income populations, leading to lower adoption rates among these populations. In addition, not all professional societies require the use of SCPs for cancer care providers to receive accreditation. This makes the adoption and use of SCPs discretionary [57]. A recent study conducted in Maryland has also reported that Black female cancer survivors are more likely to receive SCPs compared to non-Hispanic White cancer survivors [58] which could be a result of these patients having providers who are more likely to provide their patients with SCPs.

A case for risk-stratified SCPs

The IOM highlighted the need to recognize survivorship as a distinct phase in cancer care and the need to address the specific concerns of survivors [10]. Survivorship care plans serve as a roadmap for patients and as a communication tool between cancer care providers and PCPs [59]. However, enthusiasm for using SCPs has been tempered by the evidence that SCPs are not effective and are exceedingly difficult to effectively implement [16, 17]. While SCPs are still recommended for cancer patients, SCPs are no longer mandated by accreditation bodies including the Commission on Cancer (COC) [60]. Per the 2020 COC guidelines, particular elements of SCPs are not mandated [61]. Importantly, they also recommend that cancer programs define the population to receive SCPs [61].

Recent attention has been given to risk-stratified survivorship care models. Using this model, survivorship care is tailored based on risk. For example, survivors with low-risk for late effects resulting from treatment may be transitioned to receive care from PCPs, whereas high-risk groups would continue to receive more specialized care from their oncology team to manage their complex condition [62, 63]. In addition to benefiting patients, this model also benefits providers by reserving the specialty oncology clinics for patients in greater need, and not burdening PCPs with complex patients [64]. In this case, socially vulnerable survivors would be identified as high risk for poor cancer outcomes. These populations would benefit from cancer programs devoting resources to the delivery of SCPs which would also improve proximal outcomes such as adherence to follow-up and cancer coordination which could lead to improvements in distal outcomes and reductions in cancer disparities.

Needs and preferences differ by underserved group

Importantly, the provision of SCPs alone is not enough to see these potential benefits. SCPs must be implemented to meet the needs and preferences of populations of interest. This study also found that groups that are underserved have substantial unmet needs with respect to their survivorship care. Importantly, among those who do receive some form of survivorship care planning, these populations tend to report that SCPs do not meet their current needs. Similarly, other studies have found greater informational and unmet needs among African-Americans [65], other minorities [66], and low-income populations. It is also reported that differences in information needs among minorities and non-Hispanic Whites exist after controlling for income status [67]. Cancer survivors with unmet information needs are more likely to experience psychological distress and lower perceptions of health competence and well-being. Providing this population with adequate information in the form of SCPs can improve health-related quality of life and psychosocial health and reduce depression [67].

In addition, we found that the needs and preferences differ by respective population. Addressing the specific needs and preferences of a population may call for alternative methods and timing of delivery of post-treatment education and care planning. For example, Hispanic cancer survivors reported information needs in areas related to finances, continuity of care, and symptom management. Important sources of additional support for this population are patient navigators [48].

The importance of tailoring SCPs

Groups that are underserved would benefit from tailored SCPs to facilitate optimal survivorship care. This is in alignment with several studies that have identified a need for survivorship planning that is robust and individualized based on the unique needs of the population [68,69,70]. Moreover, a previous review looking at survivors’ experiences using SCPs highlighted the importance of individualized SCPs that reflect the key concerns of cancer survivors [71]. Studies also report that while cancer survivors are receptive to SCPs, they often view them as too technical [45]. It has been established that cancer survivors are frequently excluded from the development process of SCPs, resulting in care plans not being targeted to their specific needs and preferences [72].

Barriers and challenges to consider

Our study also found several barriers to the implementation of SCPs. These included costs associated with the development of SCPs such as staff time and resources, as well as a lack of coordination between primary care and oncology with respect to dissemination. Previous reviews have also found a common barrier in SCPs often not being delivered to survivors or PCPs, partly due to EHR capabilities and interoperability between systems [57]. The literature also supports the lack of organizational resources being a barrier to SCP use [17], even when mandated by professional societies. As mentioned previously, SCPs are no longer mandated by COC [60]. Importantly, the provision of SCPs to underserved populations would also require the devotion of additional resources to the implementation of SCPs. This may be burdensome for institutions whose resources are severely limited, especially minority-serving and safety-net cancer centers. In addition, professional societies may also be able to offer assistance and provide information to these institutions which highlight barriers and offer methods to facilitate their implementation and use.

Gaps in the literature

Our findings also highlight the knowledge gaps to direct future research efforts. First, oncologist perspectives were underrepresented in our review. Second, while individual-level sociodemographic factors have been assessed for their association with the receipt of SCPs, organizational factors influencing the implementation of SCPs have been understudied. Third, while studies recognize the need for culturally tailored SCPs, there were few instances of their implementation and evaluation. Lastly, few studies focused on the benefits of SCPs among groups that are underserved. For example, future research could explore the relationship between the receipt of SCPs and how it influences outcomes such as the receipt of guideline-concordant treatment and follow-up care.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this review is that it provides a systematic synthesis of the scientific evidence on the use of SCPs among groups that are underserved. While current evidence provides little support for the role of SCPs in improving health outcomes and healthcare delivery, there is evidence that it can improve the coordination of care. SCPs also serve as a communication tool between oncologists and PCPs [59]. Having these tools available may lead to patient activation among these cancer survivors, empowering them to manage, coordinate, and advocate for their survivorship care [73]. Improving care coordination and reducing barriers to care may improve health disparities and clinical outcomes among groups that are underserved.

This study has several limitations. One potential limitation is that our search strategy may not have captured all potential articles meeting our inclusion criteria. Due to variations in the definitions of SCPs, some articles may not have been included. However, we performed a snowball review of the references for included studies to minimize this. In addition, another limitation is due to the heterogeneity in study design and types of outcomes evaluated, we were unable to aggregate findings in the manner of a meta-analysis. However, the insights gleaned from the qualitative studies incorporated in our review offer valuable perspectives and enrich the depth of our findings. Our review also synthesized findings from articles of adolescent and young adult childhood cancer survivors, where it was not possible to provide the exact numbers of non-adult participants. Similarly, we included articles based on secondary analyses of data, where nearly half the sample was composed of low SES groups, but these studies did not report results specifically for these groups. Finally, the included papers may be subject to publication bias as studies that report negative findings are less likely to be published.

Conclusion

Overall, this scoping review on the use of SCPs among cancer survivors from groups that are underserved found that there were disparities in the receipt of SCPs and that the content of existing SCPs does not align with survivor needs and preferences. SCPs tailored to the specific needs of these populations in terms of content, mode, and timing of delivery are likely to improve acceptability of SCPs and facilitate better cancer care delivery.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics 2023. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2023;73(1):17–48.

Miller KD, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2022;72(5):409–36.

Miller KD, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019;69(5):363–85.

Giaquinto AN, et al. Cancer statistics for African American/Black people. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2022;72(3):202–29.

Miller KD, et al. Cancer statistics for the US Hispanic/Latino population, 2021. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(6):466–87.

Health Resources & Services Administration. What is shortage designation? 2023. Available from: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortage-designation#mups.

Green BL, et al. Cancer health disparities. In: Alberts DS, Hess LM, editors., et al., fundamentals of cancer prevention. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 199–246.

Halpern MT, McCabe MS, Burg MA. The cancer survivorship journey: models of care, disparities, barriers, and future directions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;36:231–9.

Surbone A, Halpern MT. Unequal cancer survivorship care: addressing cultural and sociodemographic disparities in the clinic. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(12):4831–3.

Hewitt ME, Ganz P. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Bellizzi KM, et al. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8884–93.

Aziz NM, Rowland JH. Trends and advances in cancer survivorship research: challenge and opportunity1. 1The ongoing need for research among long-term survivors of cancer is identified as a key initiative within the new Cancer Survivorship Extraordinary Opportunity for Research Investment - FY 2004 Bypass Budget of the National Cancer Institute. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13(3):248–66.

Faul LA, et al. Survivorship care planning in colorectal cancer: feedback from survivors & providers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(2):198–216.

Green RJ, et al. Surveillance for second primary colorectal cancer after adjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of Intergroup 0089. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(4):261–9.

Lofti-Jam K, Schofield PE, Jefford M. What constitutes ideal survivorship care? Cancer Forum. 2009;33(3):172–5.

Jacobsen PB, et al. Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2088–100.

Brennan ME, et al. Survivorship care plans in cancer: a systematic review of care plan outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(10):1899–908.

DeGuzman P, et al. Survivorship care plans: rural, low-income breast cancer survivor perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(6):692–8.

Lewis-Thames MW, et al. The use of survivorship care plans by female racial and ethnic minority breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(6):806–25.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Munn Z, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Tong A, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181.

Montague E, Perchonok J. Health and wellness technology use by historically underserved health consumers: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3):e78.

Kantsiper M, et al. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S459-66.

Trosman JR, et al. Evaluation of the novel 4R oncology care planning model in breast cancer: impact on patient self-management and care delivery in safety-net and non-safety-net centers. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(8):e1202–14.

Greenlee H, et al. Survivorship care plans and adherence to lifestyle recommendations among breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):956–63.

Hershman DL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(3):795–806.

Maly RC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of survivorship care plans among low-income, predominantly Latina breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(16):1814–21.

Casillas JN, et al. Engaging Latino adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors in their care: piloting a photonovela intervention. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36(5):971–80.

Nápoles AM, et al. Feasibility of a mobile phone app and telephone coaching survivorship care planning program among Spanish-speaking breast cancer survivors. JMIR Cancer. 2019;5(2):e13543.

Baseman J, Revere D, Baldwin LM. A mobile breast cancer survivorship care app: pilot study. JMIR Cancer. 2017;3(2):e14.

Lewis-Thames MW, et al. Understanding posttreatment patient-provider communication and follow-up care among self-identified rural cancer survivors in Illinois. J Rural Health. 2020;36(4):549–63.

Ko E, et al. Challenges for Latina breast cancer patient survivorship care in a rural US-Mexico border region. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):7024.

Casillas J, et al. How confident are young adult cancer survivors in managing their survivorship care? A report from the LIVESTRONG™ Survivorship Center of Excellence Network. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(4):371–81.

Desmond RA, Jackson BE, Waterbor JW. Disparities in cancer survivorship indicators in the deep south based on BRFSS data: recommendations for survivorship care plans. South Med J. 2017;110(3):181–7.

Jabson JM, Bowen DJ. Cancer treatment summaries and follow-up care instructions: which cancer survivors receive them? Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(5):861–71.

Linscott JA, et al. Receipt of survivorship care plans and self-reported health status among patients with genitourinary malignancy. J Urol. 2020;204(3):564–9.

Timsina LR, et al. Dissemination of cancer survivorship care plans: who is being left out? Support Care Cancer. 2021;1–8.

Wu J, et al. Disparities in receipt of follow-up care instructions among female adult cancer survivors: results from a national survey. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(3):494–500.

Sabatino SA, et al. Receipt of cancer treatment summaries and follow-up instructions among adult cancer survivors: results from a national survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):32–43.

Tawfik B, et al. Developing a survivorship care plan (SCP) delivery process for patients and primary care providers serving poor, rural, and minority patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:5021–8.

Ashing-Giwa K, et al. Are survivorship care plans responsive to African-American breast cancer survivors?: voices of survivors and advocates. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):283–91.

Burg MA, et al. The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S467-71.

Burke NJ, et al. Survivorship care plan information needs: perspectives of safety-net breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168383.

Ashing K, et al. Towards developing a bilingual treatment summary and survivorship care plan responsive to Spanish language preferred breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(4):580–94.

Tevaarwerk AJ, et al. Re-engineering survivorship care plans to support primary care needs and workflow: results from an Engineering, Primary Care and Oncology Collaborative for Survivorship Health (EPOCH). J Cancer Educ. 2022;37(6):1654–61.

Tisnado DM, et al. Perceptions of survivorship care among Latina women with breast cancer in Los Angeles County. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(2):118–29.

Ko E, et al. Development of a survivorship care plan (SCP) program for rural Latina breast cancer patients: Proyecto mariposa-application of intervention mapping. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5784.

Lyson HC, et al. Communicating critical information to cancer survivors: an assessment of survivorship care plans in use in diverse healthcare settings. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36:981–9.

Isaacson MJ, et al. Cancer survivorship care plans: processes, effective strategies, and challenges in a Northern Plains rural state. Public Health Nurs. 2018;35(4):291–8.

Stewart TP, et al. Results of engineering, primary care, oncology collaborative regarding a survey of primary care on a re-engineered survivorship care plan. J Cancer Educ. 2022;37(1):23–9.

Klemp JR, et al. Informing the delivery of cancer survivorship care in rural primary care practice. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16(1):4–12.

Psihogios AM, et al. Contextual predictors of engagement in a tailored mHealth intervention for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2021;55(12):1220–30.

Hill RE, et al. Survivorship care plans in cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of care plan outcomes. Oncologist. 2020;25(2):e351–72.

Birken SA, Mayer DK. Survivorship care planning: why is it taking so long? J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(9):1165–9.

Birken SA, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ. Survivorship care plans: prevalence and barriers to use. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):290–6.

Jin M, Jones MR, Connor AE. Racial disparities in receipt of survivorship care plans among female cancer survivors in Maryland. Front Cancer Control Soc. 2024;1:1330410.

Ganz PA. Survivorship: adult cancer survivors. Prim Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2009;36(4):721–41.

Klotz J, Kamineni P, Sutton LM. Overview of the National and International Guidelines for Care of Breast Cancer Survivors. In: Kimmick GG, Shelby RA, Sutton LM, editors. Common Issues in Breast Cancer Survivors: a practical guide to evaluation and management. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 1–10.

Blaes AH, et al. Survivorship care plans and the commission on cancer standards: the increasing need for better strategies to improve the outcome for survivors of cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(8):447–50.

McCabe MS, et al. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40(6):804–12.

Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–24.

Iyer NS, et al. Experiences with the survivorship care plan in primary care providers of childhood cancer survivors: a mixed methods approach. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1547–55.

O’Malley DM, et al. Follow-up care education and information: identifying cancer survivors in need of more guidance. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(1):63–9.

Darwish-Yassine M, et al. Evaluating long-term patient-centered outcomes following prostate cancer treatment: findings from the Michigan Prostate Cancer Survivor study. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(1):121–30.

Playdon M, et al. Health information needs and preferences in relation to survivorship care plans of long-term cancer survivors in the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors-I. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(4):674–85.

Mayer DK, et al. American society of clinical oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(6):345–51.

Stricker CT, O’Brien M. Implementing the commission on cancer standards for survivorship care plans. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:15–22.

Olagunju TO, et al. Disparities in the survivorship experience among Latina survivors of breast cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(11):2373–80.

Keesing S, McNamara B, Rosenwax L. Cancer survivors’ experiences of using survivorship care plans: a systematic review of qualitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):260–8.

de Rooij BH, et al. Factors influencing implementation of a survivorship care plan—a quantitative process evaluation of the ROGY Care trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(1):64–73.

Nissen MJ, et al. Breast and colorectal cancer survivors’ knowledge about their diagnosis and treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(1):20–32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WT proposed the study and conducted the database searches under the mentorship of EP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by WT. WT, PJ, and SR prepared Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. WT prepared the figure and appendices. All authors commented on versions of the manuscript and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tarver, W.L., Justice, Z., Jonnalagadda, P. et al. A scoping review of the evidence on survivorship care plans among minority, rural, and low-income populations. J Cancer Surviv (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01609-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01609-z