Abstract

Purpose

People of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) backgrounds face disparities in cancer care. This scoping review aims to identify the breadth of international literature focused on cancer survivorship programs/interventions specific to CALD populations, and barriers and facilitators to program participation.

Methods

Scoping review included studies focused on interventions for CALD cancer survivors after curative-intent treatment. Electronic databases: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Scopus were searched, for original research articles from database inception to April 2022.

Results

710 references were screened with 26 included: 14 randomized (54%), 6 mixed-method (23%), 4 non-randomized experimental (15%), 2 qualitative studies (8%). Most were United States-based (85%), in breast cancer survivors (88%; Table 1), of Hispanic/Latinx (54%) and Chinese (27%) backgrounds. Patient-reported outcome measures were frequently incorporated as primary endpoints (65%), or secondary endpoints (15%). 81% used multi-modal interventions with most encompassing domains of managing psychosocial (85%) or physical (77%) effects from cancer, and most were developed through community-based participatory methods (46%) or informed by earlier work by the same research groups (35%). Interventions were usually delivered by bilingual staff (88%). 17 studies (77%) met their primary endpoints, such as meeting feasibility targets or improvements in quality of life or psychological outcomes. Barriers and facilitators included cultural sensitivity, health literacy, socioeconomic status, acculturation, and access.

Conclusions

Positive outcomes were associated with cancer survivorship programs/interventions for CALD populations. As we identified only 26 studies over the last 14 years in this field, gaps surrounding provision of cancer survivorship care in CALD populations remain.

Implications for cancer survivors

Ensuring culturally sensitive and specific delivery of cancer survivorship programs and interventions is paramount in providing optimal care for survivors from CALD backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2021, census data ascertained that there are over 45 million people living in the United States who are born overseas, of which over 25 million people speak English “less than very well”.1 Outside the United States, many other predominantly English-speaking countries such as Canada and Australia also have substantial immigrant populations.2, 3 Whilst there are various terms used to refer to these populations in a healthcare setting such as non-English speaking, English second language or limited English proficiency, in Australia they are recognised as Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD), defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics as people born overseas, in countries other than those classified by the Australian Bureau of Statistics as ‘main English-speaking countries’.4 This definition is more all-encompassing, acknowledging that differences in culture between native and non-native populations signpost complexities that are not captured when focusing purely on language as a point of difference.

Within healthcare, there is increasing recognition that CALD populations face disparities in disease management although they remain relatively poorly studied. For those with a cancer diagnosis, compared with dominant ethnic populations, being from a CALD background has been linked with poorer outcomes including more treatment toxicity, low survival and poorer quality of life.5–7 Potential barriers to optimal care among people from CALD backgrounds include inadequate resources to adjust for limited English proficiency and understanding of the local health system, low health literacy and poor communication with healthcare providers.8–10 As a consequence, lack of empowerment for medical decision-making, higher unmet needs and increased distress are prevalent amongst CALD populations with cancer.11, 12

The experience of patients with cancer can also be affected by communication difficulties and perceived discrimination, as demonstrated by a number of interview-based studies, which highlighted factors such as complexity of care needs, perceived discrimination, accessibility of care, and requiring assistance with understanding and navigating health systems to be serious concerns of patients undergoing anti-cancer treatments13–15. One scoping review of 60 qualitative and mixed-methods studies identified that major themes and issues CALD patients experienced aside from communication barriers included perceived lack of rapport with healthcare professionals, and cultural safety, including religious and ethno-cultural practices and beliefs.15

Across many cancer subtypes, significant improvements in survival have led to a paradigm shift in approaching cancer as a chronic illness. However, even after completion of primary treatment, long-term treatment toxicities, physical symptoms and psychosocial issues, including symptoms of anxiety and depression, and fear of cancer recurrence, can impact quality of life adversely.16, 17 As cancer survivors who have completed cancer treatment, these patients are often encouraged to self-manage their symptoms, schedules and medications which are often complex and multifaceted. Reviews of the literature have identified that although self-management and guided self-management support interventions have been studied in survivorship populations, outcomes were heterogeneous and benefits were temporary, suggesting that interventions should be tailored to the needs of specific populations.18, 19 Additionally, accommodating for priority populations in this context, such as CALD groups, was limited, indicating a requirement to focus on specific needs and outcomes of CALD populations.

The aim of this scoping review was to explore the breadth of international literature covering this understudied topic focused upon CALD populations in the survivorship setting.

Methods

We developed a protocol using the scoping review methods proposed by Arksey and O’Malley20, refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute.21 This review was registered through the Open Science Framework.22 The PRISMA extension for scoping reviews23 was used to guide reporting.

Eligibility criteria

Our eligibility criteria were defined using ‘Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study designs, Timeframe’ (PICOST) components.24 The population of interest was cancer survivors of adult-onset cancer who have completed curative intent treatment, who were identified as being from CALD backgrounds. For the purposes of this study, we define CALD populations as those from non-English speaking backgrounds, or people born outside of the non-native country whose first language is not English. Individuals generally self-identify as CALD. This definition does not encompass Indigenous or First Nations populations as they are not migrant populations, and the historical contexts of invasion and dispossession have given way to unique sociopolitical and cultural issues impacting healthcare in these specific populations. Interventions of interest were cancer survivorship programs or interventions; defined as healthcare services, usually multidisciplinary, aiming to improve the services and care for cancer survivors through research, education and/or an understanding of the issues that affect people who have been treated for cancer.17 Studies could be of qualitative, quantitative or mixed-method design, but had to have the full-text published in English. There were no restrictions on the types of primary outcomes studied for inclusion in the review. We excluded studies focused on: childhood cancer survivors; advanced/metastatic cancer survivorship; patients with haematological cancers; African-American populations; systematic and scoping reviews; and non-peer reviewed articles, conference abstracts, dissertations and commentaries.

Information sources and search strategy

The protocol for the comprehensive search strategy was developed by LK in consultation with an Academic Liaison Librarian from the University of Sydney. The search was conducted by LK in Medline (Ovid), Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Scopus from database inception to April 30, 2022. Grey literature was not searched as it was beyond the scope of this review to analyze non-indexed journal databases. The strategy for Medline is presented as Supplementary File 1. Additional search strategies are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Study selection

Search results were imported into EndNote version 20 citation software; after initial checking the results were uploaded into Covidence for duplicate removal, two-tiered screening, and data extraction.

A series of calibration exercises prior to each stage of screening to ensure reliability across reviewers was completed. Inter-rater agreement for study inclusion was calculated using percent agreement and when it reached > 75% across the research team, we proceeded to the next stage. If the percent agreement was < 75%, the inclusion criteria were clarified, and another pilot test occurred. For abstract screening, one pilot test of 50 citations was conducted with all team members and we achieved 90% agreement. Subsequently, two reviewers (LK and WY) independently reviewed all titles and abstracts for inclusion. For full-text screening, one pilot test of 5 full-text articles was conducted, and we achieved 85% agreement. Following this calibration exercise, two reviewers (LK and WY) screened full-text articles for inclusion. All discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Data collection

For each study, data were abstracted on study characteristics including study country, ethnic population of interest, cancer type, and languages used to deliver intervention. Other variables extracted included: study design; inclusion and exclusion criteria; method of participant recruitment; sample size (at time of screening and enrolment) and recruitment rate; study aims; baseline characteristics (including age, country of birth, time spent in country, employment status, marital status, years since diagnosis, education); disease and treatment characteristics (stage at diagnosis, rates of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and hormonal therapy); study interventions (including mode of delivery, development process and cultural competence of staff delivering intervention); study endpoints and results; and dropout rates. Barriers and facilitators to survivorship care outlined or implied by authors were also recorded. The data abstraction form was developed and modified based on feedback from the study team. Data were extracted by two reviewers (LK and WY) and cross-checked by LK, with discrepancies resolved through consensus.

Methodological quality appraisal

As this was a scoping review, quality appraisal and risk of bias of studies were not assessed.

Data synthesis and charting

Extracted data were compiled into an Excel spreadsheet, from which descriptive statistical analyses were generated. Ethnic demographics of interest were categorised into Hispanic/Latina/Latino, Chinese, Asian-American or Other. For studies where more than one non-English language was used to deliver the intervention, this was recorded as single and aggregate values. Study designs were recorded as randomized controlled, non-randomized experimental, mixed-method or qualitative studies. For studies that listed initial screening sample sizes in addition to final enrolled sample sizes, the mean recruitment rate was calculated by dividing enrolled sample size by screening sample size. Dropout rates were calculated where data were available. Study endpoints were listed, and data were analysed qualitatively through content analysis to determine types of endpoints. Study interventions were listed in detail and sub-grouped as single- or multi-modal to reflect the number of components delivered, and content analyses were performed. Studies that met their primary endpoints were recorded, and for those that did not, those that met their secondary endpoints were recorded. Barriers and facilitators to cancer survivorship care were coded by reviewing manuscripts and were either identified explicitly by the authors, or implied in the results, and discussion sections of papers. Subsequent content analyses were performed and synthesized narratively, in addition to being grouped by frequency.

Results

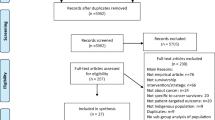

The electronic database search obtained 710 results (Fig. 1): 259 duplicates were removed and 445 records underwent abstract screening. Overall, 59 were eligible for full-text review, and 26 were included for data extraction (Table 1). The full reference list is included in Supplementary Appendix.

Demographics

Most studies were conducted in the United States (85%) and focused on breast cancer survivors (88%; Table 2). The most studied ethnic demographic was Hispanic/Latino/Latina, (54%) followed by Chinese (27%) and “Asian-American” (19%, which encompassed Chinese, Japanese and Korean). In total, 96% of programs were delivered in non-Native languages, including Spanish (46%) and Chinese (Mandarin or Cantonese, 27%).

Study designs and recruitment

In terms of study design, there were 14 randomized (54%), 6 mixed-method (23%), 4 non-randomized experimental (15%), and 2 qualitative studies (8%). All had clearly defined eligibility criteria for inclusion. Half (50%) the studies recruited participants through voluntary participation from community-based centres or advertising, followed by clinic patients (34%), mail (12%) and telephone (8%). Thirteen (50%) studies provided data on initial screening sample sizes in addition to final enrolled sample sizes, with median recruitment rate 74% (mean 62%, range 23 to 91%). Overall median sample size was 71 (mean 87, range 15 to 397). Of the 18 studies that provided information about attrition, the median dropout rate was 10% with various cited reasons such as withdrawal from intervention, loss to follow-up, lack of time or not feeling well.

Study interventions

There were several active research groups publishing in the domain of CALD survivorship with numerous papers listed overlapping authorship (Table 1), with 9 (35%) study interventions developed based on prior work by the same research group. These groups were all United States-based, and primarily focused on Spanish-speaking25–29 or Asian-American populations30–38. Twelve (46%) cited community-based participatory research methods or at least involvement of community stakeholder consultation in developing their respective interventions, and 12 (46%) were led by a steering committee. Six (23%) study interventions were developed from existing guidelines or programs. Interventions were delivered by a variety of staff including nurses (38%), doctors (31%), research staff (19%), psychologists (23%), other cancer survivors (19%), and exercise physiologists (19%). Only one (4%) of the studied interventions was fully self-administered. Staff training on cultural competence (where relevant) was mentioned in 13 studies (50%), and 23 (88%) of the studies utilized bilingual staff.

Most studies (n = 21, 81%) examined interventions with multiple components, and most delivered interventions through several avenues, including in-person, written, online, app and telephone delivery (see Table 2). Intervention program content was most focused around psychosocial domains (85%) or education about cancer (77%), with fewer studies focusing on other physical domains such as medication management (12%), exercise (12%) and diet (8%). Modes of intervention delivery included education (50%), coaching (35%), classes (12%), mentorship (8%), and through expressive writing done by participants (8%).

Endpoints and results

Most studies utilized validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), frequently as primary endpoints (n = 17, 65%), or secondary endpoints (n = 4, 15%). Of the other quantitative studies, primary endpoints studied included study-specific questionnaires (n = 3, 12%), feasibility (n = 3, 12%), and clinical-based endpoints (n = 2, 8%). Three (12%) studies were primarily qualitative in nature. PROMs encompassed a variety of variables, most commonly quality of life (46%), self-efficacy (27%), depression (23%), symptoms (19%), and anxiety, support care needs, satisfaction, and social factors (15% each). The two studies with clinical primary endpoints both examined the effects of diet or exercise interventions on Latina American breast cancer survivors.

Out of 23 quantitative studies, 17 (77%) met their primary endpoints (13 PROM, 2 feasibility, 2 clinical-based), and of the studies that did not meet their primary endpoints, 4 met at least one secondary endpoint (all PROMs). Only one study did not meet any of their endpoints. The most commonly studied PROM endpoint, quality of life, was significantly improved in 5 (42%) out of 12 studies.

Barriers and facilitators to survivorship care

Figure 2 describes the commonly identified barriers and facilitators to survivorship care interventions from this review, which include cultural sensitivity, health literacy, socioeconomic status, acculturation, and access to care.

In more detail, cultural sensitivity as a facilitator encompassed accommodation of differing cultural beliefs such as attitudes towards cancer care and family beliefs, culturally tailored delivery of care, and availability of translated written resources and bilingual staff to convey information and training to patients. Health literacy, socioeconomic status, acculturation and access to care were noted as interrelated, participant-related barriers, and were linked to issues including: intervention usability; access to technology including internet and mobile phones; increased needs for social supports especially for those with limited education backgrounds; cost to access interventions including ability to attend scheduled appointments due to family commitments or access to transport; and negative impact of low acculturation on intervention compliance and quality of life. In particular, access to care as a barrier affected participants as well as clinicians, including: lack of available electronic resources for specific population groups; limited access to care for stigmatized conditions or marginalized populations; limited technological expertise amongst healthcare professionals and institutions; in-person delivery of interventions leading to lower compliance rates; and the effect of cancer survivor empowerment and access to health professional support in improving self-efficacy and self-management.

Other themes pertaining to barriers to care which were identified less commonly but were tied into the above included compliance, duration of the intervention, health technology expertise, required prompting and self-management, underutilization of available resources and programmes, and limited English proficiency.

Discussion

This scoping review is the first to chart and synthesize existing literature around cancer survivorship programs or interventions available for survivors of CALD backgrounds. We found that cancer survivorship programs and interventions were associated with positive outcomes in populations of CALD backgrounds, and that one of the most crucial barriers and facilitators to delivering study interventions in this context pertains to cultural sensitivity.

Overall, there have been a variety of interventions studied in this space to date with several randomized studies demonstrating positive outcomes when adapting for patients from non-primary cultural or linguistic groups. Unfortunately, studies have generally been restricted to certain patient populations, geographic locations, and languages, namely breast cancer survivors in the United States of Spanish-speaking or specific Asian-language speaking backgrounds. These specifications make it difficult to generalise findings across different populations of cancer survivors.

Prior work across survivors of CALD backgrounds has demonstrated differences in the types and frequencies of unmet needs and challenges faced as compared with corresponding primary ethnocultural groups. Levesque et al. and Wu et al. all demonstrated upon literature review that the supportive needs of Asian patients, with a particular focus on Chinese patients, differ from their Caucasian counterparts as requiring increased informational and health system supports.39, 40 This was particularly associated with increased psychological needs with higher prevalence of depression and anxiety, and lower quality of life amongst Chinese patients.40 Similarly, increased supportive care needs in cancer survivorship have been demonstrated across non-native patients of Chinese, Hispanic, Arabic, Greek and Vietnamese descent from questionnaire-based or qualitative studies, suggesting that there are challenges faced by non-native populations across the board.41–45 In our review, one of the most prominent facilitators of effective care was the use of a culturally sensitive approach, thus it remains paramount that the unique needs of each cultural or linguistic group are acknowledged and health professionals be mindful not to overgeneralize findings between population groups regardless of geographic, cultural or linguistic similarities. Future work should not only focus on more prevalent non-native CALD populations, but also consider tailoring interventions towards new and emerging CALD groups.

Interventions outlined in this study were quite varied in their development, composition, and delivery. Several studies, particularly those with more complex interventional designs had a steering committee including community participants. A document analysis by Chauhan et al. revealed that out of 11 published consumer engagement frameworks in Australia between 2007 and 2019, only 4 contained sections explicitly discussing inclusion of consumers of CALD backgrounds in detail, including opportunities to improve engagement beyond language differences.46 Similar gaps in migrant healthcare policy addressing barriers to care were demonstrable in European populations,47 and although this has improved gradually over the years there remains significant heterogeneity between countries and ethnocultural populations.48, 49 Various studies have demonstrated that community-based participatory research methods, defined as “a partnership approach to research that equitably involves community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process”,50 are an effective approach to rapid development and conduct of high-quality, implementation-based research whilst simultaneously strengthening connections between academic and community members. This is especially true in conducting cross-cultural research, where it may be that researchers do not have specific insights into, nor do they have lived experiences of the issues being studied.

In our review, almost all (96%) studies had bilingual delivery (through written resources and/or bilingual speakers) of interventions available, and over half (54%) explicitly discussed staff training. As evidenced by the facilitators identified above, the cultural sensitivity of study conduct and written resources was undoubtedly an invaluable contributor to the success of the studied survivorship programs. Similarly, lower acculturation, which was only specifically studied in three studies, is thought to affect the engagement and compliance of CALD populations substantially. Whilst congruence between study populations and language is paramount to any intervention within a CALD group, the cultural aspects behind working with these populations cannot be ignored, such as differences in values, religious beliefs, health practices and socioeconomic status. This is clear from studies of professional interpreter use in the context of oncology and palliative care, which demonstrated the importance of cultural nuances alongside accurate language, however interpreters were reportedly often inadequately trained for the gravity or stress of prognostic discussions.51–53 In a systematic review of 10 studies of interpreter use in CALD populations within a palliative care setting, Silva et al. demonstrated that regular use of professional interpreters and bilingual staff members were associated with positive symptom and distress outcomes.52 Whilst supply of bilingual staff members in healthcare institutions is challenging, this review supports the existing literature that they can play a valuable role in strengthening communications, engaging communities and improving outcomes in CALD populations within the context of cancer survivorship. Given that 21 of 26 studies (81%) in this review employed relatively complex multi-modal interventions, ensuring adequate cultural and linguistic competence for all staff involved is paramount when implementing such models to maximise uptake, feasibility and optimise outcomes for these patients.

In 2019, Nekhluydov et al. developed a Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework based on existing literature and previous guidelines, with the goal of informing cancer survivorship care in clinical, research and policymaking settings.54 The framework encompasses five domains relevant to the needs of cancer survivors, which are: prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers; surveillance and management of physical effects; surveillance and management of psychosocial effects; surveillance and management of chronic medical conditions; and health promotion and disease prevention.

Based upon this framework, our review found that domains of interventions covered were heavily skewed towards surveillance and management of psychosocial (85%) and physical (77%) effects from cancer and treatment, when grouped by Cancer Survivorship care quality framework domains.54 Through the information provided in the available manuscripts and supplemental materials, the authors were unable to discern whether prevention and surveillance for new or recurrent cancers was a significant focus within any of the interventions. Whilst this is not ideal, particularly as concerns about non-adherence to recommended follow-up guidelines for various psychosocial, cultural or financial reasons, the authors understand that this presents a limitation within the review methodology. The remaining two interventional domains, health promotion and disease prevention (12%), and surveillance and management of chronic conditions (4%), were less well represented in the literature. The reasoning behind the emphasis on psychosocial and physical intervention content domains across studies is likely secondary to additional cultural complexities and linguistic limitations in resource dissemination and provision of support that is inherent in caring for CALD populations. Nevertheless, the uneven distributions across the different quality framework domains suggest that there is still work to be done in optimising all aspects of Cancer Survivorship care delivery in CALD populations, and this should be inclusive of areas where intervention delivery may be more challenging.

Outcome measures between studies were heterogeneous, but most used validated PROMs as either primary (65%) or secondary (15%) outcomes. Furthermore, it was encouraging to see that the majority of studies (77%) met their primary endpoints. These findings are unsurprising, as it is well-known that PROMs are often superior to physician assessments in capturing patient symptoms, particularly in the survivorship phase where symptom management and quality of life are priorities.55, 56 However, clinicians and researchers are now faced with a vast range of validated PROMs to choose from, each with its own pros and cons. Work is currently underway in an attempt to harmonise and protocolise PROM adoption into cancer survivorship research;57 however, within CALD populations there is further complexity in availability of translated PROMs and subsequent validation for clinical and academic use.58 As more research is conducted in various CALD communities globally, there will likely be a consequent increase in the availability of validated, translated PROMs relevant to the cancer survivorship space.

Barriers and facilitators to cancer survivorship care are an ongoing area of research worldwide. A recently published modified Delphi study outlined the highest ranked research priorities for cancer survivorship in Australia, which aligned with existing international frameworks and unmet survivorship needs.16 Specifically focusing on the Population Group research domains, ‘racially and ethnically diverse populations’ was ranked within the top 5 priorities for less than 30% of panellists, which likely reflects limitations in Delphi methodology and an urgent need for focused research across other priority population groups based upon prevalence.16 Noted priorities from this paper were also consistent with barriers and facilitators to care that were identified in our CALD-specific review, such as health services (communication, self-management, patient navigation), psychosocial (financial, distress and mood disorders), and physiological (physical activity) domains. However, our review brings to the forefront the current state of research focused on CALD populations in cancer survivorship, and there are clear unmet needs in cancer survivorship care and research in CALD populations such as fear of cancer recurrence, cognitive function, management of comorbidities and quality of survivorship care models, none of which were identified as primary subject matter within our review. The challenges moving forward for researchers in this field will be to develop high-quality, easily implementable models of survivorship care across these various domains whilst simultaneously recognising and incorporating the unique care needs of individual CALD population groups.59

There were several limitations to this study. Firstly, evaluation and comparison of the content, feasibility and efficacy of survivorship interventions between studies was superficial given this was a study-level analysis and there is substantial heterogeneity in population demographics, study designs, intervention delivery and endpoints. In particular, examination of specific intervention program content was not feasible and thus limited our appraisal of the depth of coverage in this area. This is to be expected given that this was a scoping review aiming to explore the available data, and specific comparisons between studies would be more appropriate in a future systematic review, perhaps focused upon Spanish-speaking immigrant breast cancer survivors where there is more literature available. Similarly, whilst it was recognised across various studies that substantial proportions of study participants were of lower socioeconomic backgrounds, due to the differences in reporting between studies this was not able to be discerned in further detail as individual patient data were not available. The intertwining of low acculturation, socioeconomic status and poor health literacy should remain at the forefront of researchers’ minds for the future. Finally, as the study search was limited to focusing on adult-onset, solid tumour cancer survivors who had completed primary curative-intent treatment, results from this work cannot be directly generalised to survivorship programs or interventions focused on paediatric-onset malignancy, haematologic cancers, or survivors with advanced/metastatic cancers; additional studies should be conducted specific to these groups.

Conclusion

There is a growing body of evidence to support the importance of caring for cancer survivors, particularly as prognoses improve with therapeutic advances in cancer research. Globally, efforts have been made to focus research efforts on CALD populations within the context of cancer survivorship, however this review highlights that the existing literature is strongly focused on certain population demographics, with limited patient data outside the United States or breast cancer-affected populations. Nevertheless, despite the complex, multi-modal interventional designs and heterogeneity of delivery methods it is promising to see the successes that academically driven cancer survivorship units are achieving in implementing CALD-specific survivorship research. Vast gaps in knowledge and understanding of optimal survivorship care in CALD populations continue to exist, and future research should be employing culturally sensitive methods to study conduct and delivery, utilising a consumer-involved approach to maximise feasibility and uptake for novel interventions. We challenge the existing mindset that cultural and linguistic diversities pose barriers to care in patients affected by cancer, and instead posit that a more inclusive approach would be to view culture and language as unmet needs yet to be addressed by the cancer research community.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

United States Census Bureau. https://data.census.gov/. Accessed 23rd June, 2023.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Characteristics of Recent Migrants. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/characteristics-recent-migrants/latest-release. Accessed Mar 28, 2023.

Statistics Canada. Census of Population., 2021. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm. Accessed 2nd June, 2023.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Cultural diversity of Australia: Information on country of birth, year of arrival, ancestry, language and religion. http://abs.gov.au/articles/cultural-diversity-australia. Released 20th September, 2022. Accessed 2nd June, 2023.

Chu KC, Miller BA, Springfield SA. Measures of racial/ethnic health disparities in cancer mortality rates and the influence of socioeconomic status. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1092–100.

Butow PN, Aldridge L, Bell ML, Sze M, Eisenbruch M, Jefford M, et al. Inferior health-related quality of life and psychological well-being in immigrant cancer survivors: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(8):1948–56.

Krupski TL, Sonn G, Kwan L, Maliski S, Fink A, Litwin MS. Ethnic variation in health-related quality of life among low-income men with prostate cancer. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(3):461–8.

Chou FY, Kuang LY, Lee J, Yoo GJ, Fung LC. Challenges in Cancer Self-management of patients with Limited English proficiency. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2016;3(3):259–65.

Levesque J, Gerges M, Girgis A. Psychosocial Experiences, Challenges, And Coping Strategies Of Chinese–Australian Women With Breast Cancer. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2020;7(2):141 − 50.

Luckett TG, /Butow D, Gebski PN, /Aldridge V, /McGrane LJ, Ng J, King W. Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(13):1240–8.

Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of african american, asian american, Latina and caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(6):408–28.

Jefford M, Tattersall MH. Informing and involving cancer patients in their own care. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(10):629–37.

O’Callaghan C, Schofield P, Butow P, Nolte L, Price M, Tsintziras S, et al. I might not have cancer if you didn’t mention it”: a qualitative study on information needed by culturally diverse cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(1):409–18.

Tan L, Gallego G, Nguyen TTC, Bokey L, Reath J. Perceptions of shared care among survivors of colorectal cancer from non-english-speaking and english-speaking backgrounds: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):134.

Yeheskel A, Rawal S. Exploring the ‘Patient experience’ of individuals with Limited English proficiency: a scoping review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(4):853–78.

Crawford-Williams F, Koczwara B, Chan RJ, Vardy J, Lisy K, Morris J, et al. Defining research and infrastructure priorities for cancer survivorship in Australia: a modified Delphi study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:3805.

Vardy JL, Chan RJ, Koczwara B, Lisy K, Cohn RJ, Joske D, et al. Clinical Oncology Society of Australia position statement on cancer survivorship care. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48(12):833–6.

Budhwani S, Wodchis WP, Zimmermann C, Moineddin R, Howell D. Self-management, self-management support needs and interventions in advanced cancer: a scoping review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9(1):12–25.

Boland L, Bennett K, Connolly D. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1585–95.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

Open Science Framework. Cancer Survivorship Programs in patients from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) Backgrounds: a scoping review. Date created: 20th April; 2022. https://osf.io/pyrbf/

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Sarri G, Patorno E, Yuan H, Guo JJ, Bennett D, Wen X, et al. Framework for the synthesis of non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials: a guidance on conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis for healthcare decision making. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2022;27(2):109–19.

Napoles A, Santoyo-Olsson J, Chacon L, Stewart A, Dixit N, Ortiz C. Feasibility of a smartphone application and telephone coaching survivorship care planning program among spanish-speaking breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(1 Supplement):226–S7.

Nápoles AM, Ortíz C, Santoyo-Olsson J, Stewart AL, Gregorich S, Lee HE, et al. Nuevo Amanecer: results of a randomized controlled trial of a community-based, peer-delivered stress management intervention to improve quality of life in Latinas with breast cancer. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):e55–63.

Nápoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Stewart AL, Ortiz C, Samayoa C, Torres-Nguyen A, et al. Nuevo Amanecer-II: results of a randomized controlled trial of a community-based participatory, peer-delivered stress management intervention for rural Latina breast cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2020;29(11):1802–14.

Buscemi J, Buitrago D, Iacobelli F, Penedo F, Maciel C, Guitleman J, et al. Feasibility of a smartphone-based pilot intervention for hispanic breast cancer survivors: a brief report. Translational Behav Med. 2019;9(4):638–45.

Yanez B, Oswald LB, Baik SH, Buitrago D, Iacobelli F, Perez-Tamayo A, et al. Brief culturally informed smartphone interventions decrease breast cancer symptom burden among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2020;29(1):195–203.

Im E-O, Kim S, Lee C, Chee E, Mao JJ, Chee W. Decreasing menopausal symptoms of asian american breast cancer survivors through a technology-based information and coaching/support program. Menopause. 2019;26(4).

Im E-O, Kim S, Yang YL, Chee W. The efficacy of a technology-based information and coaching/support program on pain and symptoms in asian american survivors of breast cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(3):670–80.

Im EO, Yi JS, Kim H, Chee W. A technology-based information and coaching/support program and self-efficacy of asian american breast cancer survivors. Res Nurs Health. 2021;44(1):37–46.

Chu Q, Lu Q, Wong CCY. Acculturation Moderates the Effects of expressive writing on post-traumatic stress symptoms among chinese american breast Cancer Survivors. Int J Behav Med. 2019;26(2):185–94.

Lu Q, You J, Man J, Loh A, Young L. Evaluating a culturally tailored peer-mentoring and education pilot intervention among chinese breast Cancer Survivors using a mixed-methods Approach. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(6):629–37.

Lu Q, Zheng D, Young L, Kagawa-Singer M, Loh A. A pilot study of expressive writing intervention among chinese-speaking breast cancer survivors. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology American Psychological Association. 2012;31(5):548–51.

Warmoth K, Yeung NCY, Xie J, Feng H, Loh A, Young L, et al. Benefits of a psychosocial intervention on positive affect and posttraumatic growth for chinese american breast Cancer Survivors: a pilot study. Behav Med. 2020;46(1):34–42.

Chee W, Lee Y, Im EO, Chee E, Tsai HM, Nishigaki M, et al. A culturally tailored internet cancer support group for asian american breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled pilot intervention study. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(6):618–26.

Chee W, Lee Y, Ji X, Chee E, Im EO. The preliminary efficacy of a technology-based Cancer Pain Management Program among asian american breast Cancer Survivors. Comput Inf Nurs. 2020;38(3):139–47.

Levesque JV, Girgis A, Koczwara B, Kwok C, Singh-Carlson S, Lambert S. Integrative review of the supportive care needs of asian and caucasian women with breast Cancer. Curr Breast Cancer Rep. 2015;7(3):127–42.

Wu VS, Smith AB, Girgis A. The unmet supportive care needs of chinese patients and caregivers affected by cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2022;31(6):e13269.

Alananzeh IM, Levesque JV, Kwok C, Salamonson Y, Everett B. The unmet supportive care needs of arab australian and arab jordanian cancer survivors: an international comparative survey. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(3):E51–E60.

Moreno PI, Ramirez AG, San Miguel-Majors SL, Castillo L, Fox RS, Gallion KJ, et al. Unmet supportive care needs in Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors: prevalence and associations with patient-provider communication, satisfaction with cancer care, and symptom burden. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(4):1383–94.

Butow PN, Aldridge L, Bell ML, Sze M, Eisenbruch M, Jefford M, et al. Inferior health-related quality of life and psychological well-being in immigrant cancer survivors: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(8):1948–56.

Gerges M, Smith AB, Durcinoska I, Yan H, Girgis A. Exploring levels and correlates of health literacy in arabic and vietnamese immigrant patients with cancer and their english-speaking counterparts in Australia: a cross-sectional study protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7) (no pagination).

Lim BT, Butow P, Mills J, Miller A, Pearce A, Goldstein D. Challenges and perceived unmet needs of chinese migrants affected by cancer: Focus group findings. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(3):383–97.

Chauhan A, Walpola RL, Manias E, Seale H, Walton M, Wilson C, et al. How do health services engage culturally and linguistically diverse consumers? An analysis of consumer engagement frameworks in Australia. Health Expect. 2021;24(5):1747–62.

Mladovsky P, Rechel B, Ingleby D, McKee M. Responding to diversity: an exploratory study of migrant health policies in Europe. Health Policy. 2012;105(1):1–9.

Lebano A, Hamed S, Bradby H, Gil-Salmerón A, Durá-Ferrandis E, Garcés-Ferrer J, et al. Migrants’ and refugees’ health status and healthcare in Europe: a scoping literature review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1039.

Ledoux C, Pilot E, Diaz E, Krafft T. Migrants’ access to healthcare services within the European Union: a content analysis of policy documents in Ireland, Portugal and Spain. Global Health. 2018;14(1):57.

Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J, The Leap Advisory B, Straits KJE, Gil-Kashiwabara E, et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol. 2018;73(7):884–98.

Silva MD, Tsai S, Sobota RM, Abel BT, Reid MC, Adelman RD. Missed Opportunities when communicating with Limited English-Proficient Patients during End-of-life conversations: insights from spanish-speaking and chinese-speaking medical interpreters. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2019.

Silva MD, Genoff M, Zaballa A, Jewell S, Stabler S, Gany FM, et al. Interpreting at the end of life: a systematic review of the impact of interpreters on the delivery of Palliative Care Services to Cancer patients with Limited English proficiency. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(3):569–80.

Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Kerr K, O’Riordan D, Pantilat SZ. Interpretation for discussions about end-of-life issues: results from a National Survey of Health Care Interpreters. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(9):1019–26.

Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework: implications for Clinical Care, Research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(11):1120–30.

Xiao C, Polomano R, Bruner DW. Comparison between patient-reported and clinician-observed symptoms in oncology. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(6):E1–e16.

Gordon BE, Chen RC. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivorship. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):166–73.

Ramsey I, Corsini N, Hutchinson AD, Marker J, Eckert M. Development of a Core Set of patient-reported outcomes for Population-Based Cancer Survivorship Research: protocol for an australian Consensus Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(1):e14544.

McKown S, Acquadro C, Anfray C, Arnold B, Eremenco S, Giroudet C, et al. Good practices for the translation, cultural adaptation, and linguistic validation of clinician-reported outcome, observer-reported outcome, and performance outcome measures. J Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2020;4(1):89.

Chan RJ, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Joseph R, Hart NH, Milley K, et al. Effectiveness and implementation of models of cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17(1):197–221.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Tess Aitken, Academic Liaison Librarian at the University of Sydney for her assistance with developing the literature search strategy.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Lawrence Kasherman is being supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council 2022 Postgraduate Scholarship (2021964) through the University of Sydney, and previously received a PhD scholarship from Sydney Cancer Partners through funding from the Cancer Institute NSW (2021/CBG0002). Janette Vardy is supported by a National Health Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (APP1176221).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Literature search was performed by Lawrence Kasherman. Reference, abstract, and full text screening were performed by Lawrence Kasherman and Won-Hee Yoon. Data extraction was performed by Won-Hee Yoon. Data analysis was performed by Lawrence Kasherman. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Lawrence Kasherman and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Figure and table creation was done by Lawrence Kasherman. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was a scoping review of the literature and did not require ethics approval.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kasherman, L., Yoon, WH., Tan, S.Y. et al. Cancer survivorship programs for patients from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds: a scoping review. J Cancer Surviv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01442-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01442-w