Abstract

We analyze the impact of the broad range of state labor regulations on employment and annual earnings in manufacturing for wage earners and salaried workers using a new panel data set for the 48 US states in 1904, 1909, 1914, and 1919. The effects of state labor regulations influenced the labor market for wage earners and had virtually no effect on the market for salaried workers. Fixed effects analysis shows that increases in a newly developed labor law index were associated with a rise in employment and a decline in earnings for wage workers. These changes imply a dominant rise in labor supply that reflected marginal benefits for workers that were higher than the marginal costs or marginal benefits to employers. After the demand and supply shifts were completed, both workers and employers ultimately experienced improved gains from trade. Under a wide range of assumptions about the earnings elasticity of demand, the results are also consistent with the regulation increasing labor demand and thus providing positive marginal benefits to employers. The effects of appropriations per gainfully employed worker were much smaller and depended on the size of the law index.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, state governments in the USA began regulating conditions in labor markets. In the US federal system, the states had the responsibility for labor regulation. As a result, the extent of regulation varied substantially across time and place. Most states established bureaus to collect labor statistics and regulatory bodies to inspect boilers, factories, and mines. Many states passed employer liability laws to expand the liability of employers for workplace accidents and then replaced negligence liability with shared strict liability in the form of workers’ compensation laws. States established limits for child labor and women’s hours. Some states passed laws that promoted unionization by outlawing “yellow dog” contracts and protecting union trademarks and labels. Other states seemed bent on limiting unionization with the passage of anti-enticement laws and laws that limited picketing and reduced intimidation of non-union workers.

A growing literature examines the quantitative impact on labor markets of the leading progressive laws in the late 1800s and early 1900s.Footnote 1 While each of the studies provides invaluable evidence on how the individual laws influence specific aspects of the labor market, they do not measure the impact of the overall legal climate for workers during the period. This is problematic because a state’s reputation for being pro-labor or anti-labor was not based on one or two specific laws, and it was based on a broad range of laws that covered many sectors and dealt with a wide range of components of the labor contract, including wages, hours, unionization, safety, comfort at work, child labor, compensation for accidents, enforcement of the laws, and employment opportunities.Footnote 2 These are all issues of interest to workers and employers, and under several of these categories, there were numerous types of laws that influenced the situation. The state’s labor climate reputation was built up over various waves of specific labor legislation covering an extended period.

We develop a comprehensive measure of the labor regulatory climate and then examine the relationship between the comprehensive measure and annual earnings and employment in fixed effects estimation. On several occasions, the US Commissioner of Labor and later the Bureau of Labor Statistics documented the extent of state labor legislation in the various states. The Labor Department reported on roughly 135 laws that influenced labor markets and workplace conditions. After combining the information from the Labor Department with information on the timing of legislation from Legislative Acts, we use the presence of these labor laws to develop an index of the 82 laws that characterize the regulatory climate for manufacturing in the various states and how that climate changed over time. We then examine how the regulatory climate influenced annual earnings and employment in state manufacturing labor markets using state level panel data with controls for unionization, demographics, and other information from the Censuses of Manufacturing between 1904 and 1919. The coefficients from that analysis are then used to provide estimates of the changes in labor demand and labor supply associated with the labor law climate.

The results of the analysis provide new information about who benefitted from the passage of the labor laws. Scholars who study American labor laws hold different opinions about who gained and lost from state labor regulation. A number of traditional labor historians see many of the regulations as examples of victories for workers over employers that improved the quality of the conditions that they faced. If that were the case, the regulations would have caused workers to increase their supply of labor and/or employers would have reduced their labor demand. Yet, some scholars have found that major employers played substantial roles in the passage of labor legislation. If so, the laws might have been win–win situations for both employers and workers, and we would expect the employers’ demand for labor to rise along with an increase in labor supply. If the laws were advantageous for major employers while providing little gain for workers, labor demand would have risen, and labor supply would have been left unchanged.

The empirical estimates of the elasticities of the wage workers’ employment with respect to an index of labor laws show that increases in the labor law index were associated with higher employment and lower earnings. The changes are consistent with a dominant rise in labor supply in which the direct marginal benefits to workers exceeded the direct marginal costs or marginal benefits to employers. At the new equilibrium after the shifts, both workers and employers had higher gains from trade than before the regulation. Under a wide range of assumptions about the earnings elasticity of demand, the results are also consistent with employers receiving a direct marginal benefit from the regulatory climate.

The elasticities of demand and supply with respect to spending appropriations per gainfully employed worker were much smaller and varied with the size of the labor law index. In state years with higher labor law indexes, the results suggest that both workers and employers gained from more appropriations. At lower levels of the labor law indices, it appears that the direct marginal costs to employers from the appropriations exceeded the direct marginal benefits to the workers.

2 Who gained and who lost from progressive era labor legislation

The Progressive Era has received a tremendous amount of attention in the social science literature, in part because the states and municipalities experimented with so many types of reforms. The USA was similar to a laboratory with an enormous variety of projects going on simultaneously. There is no consensus on the exact timing and boundaries of the Progressive Era nor on the driving force behind it. Some writers focus on muckraking reformers, while others emphasize the role of middle-class, social conservatives who were dissatisfied with an existing political system that seemed to be controlled by political bosses. Many see a role for religious attitudes that contributed to pressure for egalitarian reforms. Still others see the Progressive reforms as a response to increased industrialization, modernization, and urbanization (Buenker et al. 1977; Gould 1974; Hofstadter 1955).

In examining the introduction of Progressive Era labor legislation, we have found it most useful to think of the driving forces as a complex interaction of interest groups and coalitions (Becker 1983; Pelzman 1976; Stigler 1971). In the area of labor legislation, the key broad interest groups were workers, employers, and social reformers. Some labor history studies suggest that Progressive Era social reformers, workers, and unions were the key coalitions that led to the passage of the legislation over recalcitrant employers; therefore, the laws likely led to direct marginal benefits for workers and imposed marginal costs on employers. On the other hand, Wiebe (1962), Kolko (1963), Weinstein (1967), Lubove (1967), Moss (1996), and Fishback and Kantor (2000) found substantial evidence that leading employers and businessmen played important roles in the passage of Progressive Era labor legislation. In fact, union leaders in the early 1900s suggested that business interests had significant control of state politics and therefore they distrusted some political solutions (Weinstein 1967, 159; Skocpol 1992, 205–47). These fears were confirmed in some states where anti-union legislation was passed or when federal antitrust legislation was applied more to busting unions than to busting trusts (Witte 1969).

The legislative histories of many laws suggest that there was a significant amount of negotiation over these laws and compromises often resulted. Fishback (1998) surveyed a series of quantitative studies of child labor laws, women’s hours laws, and safety legislation that found that the laws generally had small effects on child labor, women’s hours, and accidents. He suggested that these small effects came about because employers were powerful enough in state legislatures that they could significantly change the legislation proposed by reformers. Working conditions at large companies were often better than at smaller companies, and the leading employers negotiated with the workers and reformers to force all employers to adopt the existing practices of leading employers. In this setting, the leading employers gained from forcing lagging employers to follow their practices, and workers gained from better working conditions.

There is also the possibility that labor legislation provided marginal benefits to both employers and workers. For example, Fishback and Kantor (2000) suggest that workers’ compensation laws passed because enough employers, workers, and insurers (in states without state funds) anticipated gains from the new law. The question then arises as to why employers and workers did not privately contract on their own for the changes enacted by the labor legislation. Private contracting for workers’ compensation policies in which workers waived their rights to negligence suits in advance had been disallowed by a mixture of private legislation and court decisions. With respect to other regulations, there may have been situations where employers and workers in many states thought the changes would be a good idea but that they would have been put at a competitive disadvantage within their own state if they unilaterally made the move on their own. Thus, the legislation may have helped prevent a “race to the bottom.”Footnote 3

One way to tell who gained from the legislation is to examine what happened to labor demand and labor supply for the wage earners who typically worked in production. If employers gained from the passage of the law, as Fishback and Kantor argued for workers’ compensation, they received direct marginal benefits from the regulation, which would have raised demand for workers, putting upward pressure on earnings and employment. On the other hand, the laws might have acted as a “tax” on the employers, raising their nonwage direct marginal costs of hiring labor, and thus reducing their demand for labor, putting downward pressure on earnings and employment. Such changes also might have caused employers to shift toward other inputs that were substitutes for labor while reducing inputs that were complementary to labor. Safety legislation might have required employers to use more capital or to choose labor saving devices that led to higher capital expenditures.

On the labor supply side, legislation that workers found to be valuable would have provided direct marginal benefits of nonwage working conditions, and they would have been willing to accept lower wages leading to an increase in the supply of labor as the nonwage working conditions for workers improved. The rise in labor supply would have put downward pressure on earnings and upward pressure on employment. Laws that raised the direct marginal cost of working would have led to reductions in labor supply that led to less employment and higher earnings.

The direct costs or benefits of a regulation that shifts demand or supply in the labor market do not fully describe who gained or lost from a regulation at the new wage and employment levels. When demand sloped downward and supply sloped upward in the labor market, the marginal benefits (or costs) of regulations to workers were shared with employers, and vice versa. The sharing was based on the elasticities with respect to earnings of demand and supply. Two graphs help illustrate the point.

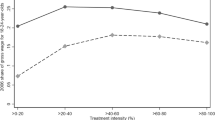

The graph in Fig. 1 shows a situation where a labor regulation imposes no cost on the employers but makes each worker better off by a marginal benefit of MB dollars. Before the regulation, earnings were Wo and Employment was Eo. When the regulation is introduced, the workers’ supply shifts down by MB per worker from So to Sr because each worker would have reservation earnings that were $MB lower because of the improved conditions. At the new equilibrium that develops at the intersection of demand Do and supply Sr, employment rises from Eo to Er. The earnings paid by employers to workers fall from $Wo to $Wr, but the workers also receive the benefits of $MB per worker from the regulation; therefore, the marginal value of the employment package with the new wage $Wr and the marginal benefit from the regulation MB is valued at Wr + MB, which is higher than the original wage Wo. Using the original supply So as a baseline for comparison, the workers’ gains from trade rise from area DH before the regulation to area BCDH after the regulation. The employers also share in the gains from the regulation because the wage they pay falls from Wo to Wr and the number of workers they hire rises from Eo to Er. As a result, the employers’ gains from trade rise from area AB to area ABDEF. Note that the earnings fall, and employment rises. In the next section, we show how to use the elasticities of earnings and employment with respect to labor regulations to infer the gains and losses from the regulation.Footnote 4

It is likely that a regulation that benefits workers would lead to costs for employers. In Fig. 2, each worker gains a direct marginal benefit equal to MB from the regulation that increases labor supply from So to Sr. Meanwhile, the employers pay a direct marginal compliance cost MC per worker that is lower than the MB per worker and reduces labor demand from Do to Dr. The shifts lead to a new intersection of supply Sr and demand Dr in which the market earnings paid by employers fall from Wo to Wr and employment rises from Eo to Er. The overall marginal value of the employment package to workers rises from Wo, the original wage, to Wr + MB, which includes the new earnings Wr and the marginal benefit MB of the better worker conditions. Using the original supply So for comparison, the workers’ total gains from trade rise from area FGKQ before the regulation to area CDEFGKQ with the regulation in place. The full marginal cost to employers of hiring workers falls from Wo before the regulation to Wr + MC, which is composed of the new lower earnings Wr and the marginal cost MC of compliance after the regulation. Using the original demand Do for comparison, total gains from trade to the employer thus rise from area BC before the regulation to area BCFGHI after the regulation. Both the workers and employers gain from the rise in employment from Eo to Er, and they share the difference between marginal benefit and marginal cost, MB-MC. The workers’ marginal gain over the original wage Wo is Wr + MB-Wo, and the employers’ marginal gain is Wo-Wr-MC.

Intuitively, even though employers faced direct marginal costs from complying with the regulation, their costs were more than offset by the higher direct marginal benefits that workers experienced from the improvement in their working conditions. The workers lowered their reservation earnings enough that employers were able to hire more workers with a lower cost wage and working condition package than before. Meanwhile, more workers were hired with a more highly valued employment package than before.

3 Empirical estimation of the relationships between labor laws and labor supply and demand

Ideally, we would be able to directly estimate both the demand (d) and supply elasticities (s) with respect to the labor law measures for wage workers from the following labor demand and labor supply equations:

The variable lnEit is the natural log of average employment of wage earners in manufacturing in year t and state i; lnWit is the natural log of average annual earnings of wage earners in manufacturing in year t and state i; and lnLawsit is the natural log of the measure(s) of labor legislation. The term lnYit is a vector of natural logs of demand correlates and lnZit is a vector of natural logs of supply correlates; YFEdt and YFEst are vectors of year fixed effects, and SFEdt and SFEst are vectors of state fixed effects, and vdit and vsit are combinations of unmeasured factors and stochastic error terms. The coefficient d for the law variable is read as an elasticity that shows the percentage change in quantity demanded associated with a one percent change in the labor law measure, while holding fixed the log of annual earnings, the correlates in lnYit, unchanging factors in the state, and nationwide annual shocks. The coefficient s is the supply elasticity of employment with respect to the law measure, while holding the factors in that equation constant.

We know that labor demand and labor supply simultaneously and endogenously determine wages and employment. To resolve the labor supply and demand endogeneity and simultaneity problems related to wages and employment, we would have to find at least one variable in the vector of demand shifters (lnYit) that does not belong in the vector of supply shifters (lnZit) and vice versa. So far, we have not found correlates that varied across both years and states in the early 1900s that we believe meet that standard.

We therefore follow an alternative strategy in which we infer the signs of the labor demand and labor supply elasticities with respect to the law measures by estimating reduced form Eq. 2a) with the earnings measure (lnWit) as a function of all the correlates in Eqs. 1a) and 1b) and Eq. 2b) with the employment measure (lnEit) as a function of all of the correlates in Eqs. 1a) and 1b).

The measures of labor legislation represented by lnLawsit include the labor law index and real labor regulation expenditures per gainful worker. We estimate specifications with only one of the measures, with both measures, and with both measures and an interaction term. The vector lnXit includes all of the variables in lnYit and lnZit from the labor demand and supply Eqs. 1a) and 1b). In the analysis below, these include a measure of union strength based on the national union share in various industries and the industry mix in the state, an interaction term between a dummy variable for southern states and the union measure, and trend estimates between 1900, 1910, and 1920 of population, percent black, percent foreign born, percent urban, and percent illiterate. The coefficients and the error terms in Eqs. 2a) and 2b) are functions of the labor demand and supply elasticities and error terms in Eqs. 1a) and 1b). We can then use the combination of signs of the elasticity of employment with respect to the labor laws (e in Eq. 2b) and of the elasticity of earnings with respect to the labor laws (w from Eq. 2a) to infer how labor demand and labor supply shifted in response to an increase in the labor law measure. This information tells us whether workers or employers expected gains or losses from the laws.

These inferences are shown in Table 1 and are based on the type of analysis performed in Figs. 1, 2, and the algebraic calculations are in Appendix F. Table 1 shows the relationships between different combinations of earnings and employment elasticities with respect to the law measures, the ultimate gains and losses to workers and employers derived from the analyses illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, the relative sizes of the changes in marginal benefits and marginal costs to workers and employers, and the relative sizes of shifts in labor demand and supply. In building Table 1, we assume that the labor market demand elasticity with respect to earnings is negative and the labor market supply elasticity with respect to earnings is positive.

The key to determining the ultimate gains and losses from the regulations is the sign of the employment elasticity. When it is positive, as in rows 1 through 7, both employers and workers ultimately gain from the regulation. When a positive employment elasticity is combined with a negative earnings elasticity in rows 1 through 3, the workers’ direct marginal benefit is larger than the employer’s direct marginal benefit or direct marginal cost. When the positive employment elasticity is combined with a positive earnings elasticity in rows 4 through 6, the employers’ direct marginal benefit is larger than the workers’ direct marginal benefit or cost. When the positive employment elasticity is combined with a zero earnings elasticity in row 7, the direct marginal benefits are the same for workers and employers.Footnote 5

When the employment elasticity is zero, the ultimate gains from trade to both workers and employers do not change, either because there was no effect in row 17 or because the employers’ marginal cost is the same as the workers’ marginal benefit in row 15 or vice versa in row 16. When the employment elasticity with respect to regulation is negative, both employers and workers ultimately lose from the regulation, while the sign of the earnings elasticity determines whether it is the workers (rows 11–13) or the employers (8–10) who have the higher direct marginal cost.

We can tease out some more information about the direct marginal benefits and marginal costs for workers and employer by making assumptions about the absolute values of the demand elasticity of employment with respect to earnings (a1 in Eq. 1a) and the supply elasticity of employment with respect to earnings (b1 in Eq. 1b).

When the labor demand and labor supply functions are log linear, as assumed here, the derivations in Appendix B show that the law coefficient (d) in demand Eq. 1a) and the law coefficient (s) in supply Eq. 1b) can be written as functions of the elasticities of employment with respect to earnings (a1 and b1) from Eqs. 1a) and 1b) and the elasticities of earnings and employment with respect to the law index (e and w) from Eqs. 2a) and 2b).

We also show in Appendix G that—for the log–log specification we are using—Eqs. 3a and 3b will be the same whether we assume a competitive labor market, a fully unionized market, or a market with a monopsonist employer. If labor demand and supply take a log–log functional form, all demand and supply elasticities are constant. Therefore, the elasticities will not depend on where the equilibrium occurs. Different assumptions about the market structure for labor will change the location of the labor market equilibrium, but not the elasticities that prevail at the equilibrium.

4 The patterns of state labor legislation

State labor legislation came in several waves. In the late 1800s, a number of northeastern and eastern midwestern states began establishing bureaus of labor, created positions for factory inspectors and set up a series of factory regulations, passed the early child labor laws, refined the nature of accident liability for employers, provided political protections for workers as voters, and established a series of laws that gave unions more legal status. A number of mining states established the early regulations for mines and the first mining inspectors. In the first decade of the twentieth century, the early forms of labor legislation spread to a majority of states and existing laws were refined and updated. The second wave of legislation followed in the 1910s as states became more involved with social insurance, introducing mothers’ pensions, and replacing the employer liability system with the statutory rules of workers’ compensation. Nearly half of the states passed women’s hours laws during this period and about 20 percent established some form of minimum wages for women and children. At the same time, many states reorganized their state labor bureaucracies into industrial commissions and some established child labor commissions.

Since the number and range of state labor laws are extensive and there are only 48 states, we have sought effective ways to summarize the information in just a few variables. We have aimed to develop measures that give a sense of the labor regulatory climate in the various states. We experimented with using principal component analysis to characterize common influences among the many laws, but such an analysis leads to comparisons as to which states are most alike in the laws that they have, but do not provide a metric for how much of the legislation was adopted or for the relative weakness or strength of the legislation (Fishback et al. 2009). In this paper, we use a weighted sum of laws related to manufacturing in each state for each year. In each state, the law is weighted by the share of manufacturing employment that is covered by the law. As examples, if the law is specific to cotton textiles, which accounted for 10 percent of manufacturing employment, the law will have a value of 0.10 when the number of laws are added up in the child labor portion when creating the index. If child labor accounted for 3 percent of employment, the child labor index is given a weight of 0.03 when calculating the overall index, and a similar practice was followed for laws for women. The weights are based on the employment shares at the national level to avoid any endogeneity that might arise from using state employment shares.Footnote 6

Appendix A provides information on the number of states that had adopted each type of law as of 1903 and 1918 and shows the formula for constructing indices for 8 types of labor laws and an overall labor law index. There were 135 labor laws that were reported on by the Commissioner of Labor (1896, 1904, 1908) and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (1914, 1925) in their volumes on “Labor Laws in the United States,” and Holmes (2003) created digital measures for each of the laws. We examined the original state legislative acts and Commons and Associates (1966) to fill in gaps in the timing of the laws. There were 82 laws enacted by 1918 that related either to all employment, specifically to manufacturing employment, specifically to certain industries, or specifically to women and children.

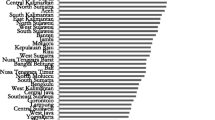

The variation in the state manufacturing labor law indices across states in 1903, 1908, and 1918 is shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5. The positive slopes in Figs. 3, 4 suggest a significant amount of persistence in the state labor law rankings between 1903 and 1918. Massachusetts, Wisconsin, New York, and Minnesota rank highly in all years. Meanwhile, Vermont, Alabama, and Mississippi tend to have the least amount of regulation in each period. Between 1903 and 1908 in Fig. 3, most states were slightly above the diagonal line, suggesting relatively small increases in the labor law activity. The comparisons in Fig. 4 show that there were much larger increases in labor law activity between 1908 and 1918. Oklahoma, Texas, New Hampshire, and Nevada were states that experienced large increases in the labor index that carried them from below the median to above the median for the period. Meanwhile, Massachusetts, Ohio, and California started with high values in 1903 and still sharply increased the extent of their labor laws. Vermont, Arizona, Arkansas, and Idaho experienced substantial increases in their labor laws, but started at such a low level that they never made it past the median level.

Changes in the indices were driven to different degrees by the specific laws that make up the index. Most of the action in state laws between 1903 and 1918, the period for the econometric analysis, came in several categories. Thirty-seven states introduced workers’ compensation laws during the period. The number of states providing free employment offices to aid workers looking for work rose from 10 to 23. Quite a few states enacted laws related to working conditions in factories, as the number of states with laws about bathrooms and sanitation rose from 20 to 32, factory ventilation from 18 to 25, guards and safety rules on machinery from 20 to 34, building standards from 9 to 23, and fire escapes from 28 to 35. The number of states with factory inspector laws rose from 24 to 39, while the number of states with laws requiring accident reports rose from 12 to 22, while the number requiring occupational disease reporting rose from 12 to 22.

A number of states added new legislation related to women’s work. Minimum wage laws for women and children were enacted in 12 states, while the number of states with general limits on women’s hours rose from 7 to 23 and 8 new states passed hours laws for specific types of women’s work. The number of states with laws requiring seats and other forms of comfort for women rose from 31 to 43.

The share of children in the labor force was falling during the early 1900s, while quite a few states added several forms of child labor laws. The number of states establishing a minimum age for children to work at night rose from 17 to 40, limiting child hours rose from 9 to 29, restricting the use of children to clean machinery rose from 14 to 36. Enforcement of the child labor laws was enhanced when the number of states with a child labor inspector rose from 18 to 39 and the number with fines for false age certification rose from 28 to 44.

The states left legislation related to unionization unchanged for most categories. The changes that did occur tended to be situations where states adopted more anti-union legislation. The number of states prohibiting armed guards fell from 16 to 8 while the number stating that industrial police were legal rose from 6 to 19. The number that had laws banning “yellow dog” contracts fell from 17 to 12. On the corruption front, there was more anti-bribery legislation. The number of states making bribes to foremen to obtain employment illegal rose from 2 to 12 and the number banning bribes to employees rose from 0 to 17. For more details on the changes in state laws, see Appendix A.

5 Appropriations by states on labor issues

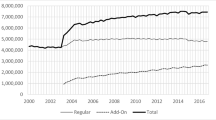

The presence of state laws offers one indication of the regulatory climate for labor markets in the states. Laws on the books have more impact if resources are allocated to enforce them. We collected information from the legislative statutes on the appropriations for the state labor department, board of arbitration, free employment offices, mining inspection, boiler inspection, and other factors related to labor markets. The labor appropriations per gainfully employed worker (LAPGEW) are positively correlated (0.55) with our constructed index for the laws relevant for manufacturing.

The large number of states in the upper left quadrant of Fig. 6 shows that most states increased their real expenditures (1967$) on labor regulation between 1903 and 1918. This figure focuses on all labor regulation including mining regulation. Therefore, some state spending figures are overstated relative to what they spent on manufacturing regulation. For example, the biggest spenders were the western states in part because they had a heavy emphasis on mining regulation and relatively few workers outside mining. Among the non-mining states, New York and Massachusetts had the largest expenditures in both time periods. North Carolina and Florida were the laggards in both periods.

The states’ enactments of labor laws potentially were also endogenously influenced by earnings and employment. We work to reduce this problem in several ways. First, the state fixed effects are included to reduce omitted variable bias that might arise from factors in each state that did not vary across time but varied across states. These included natural resources and access to water transport that gave specific states advantages in different types of manufacturing. Second, the year fixed effects are included to reduce omitted variable bias that might arise from nationwide shocks. The largest shock was the impact of the First World War, which started in the second half of 1914, and began to influence the demand for American goods. America entered the war directly in April 1917 and the War concluded in November 1918 and experienced the repercussions of transition out of war footing in 1919. The variation used to estimate the coefficients is therefore changes across time within the same state after controlling for national shocks. Third, in Appendix C we show that the states with high and low average levels of regulation during our estimation period had similar pre-trends for similar measures of the dependent variables during the pre-study period from 1870 to 1900.Footnote 7 Fourth, in Appendix D we ran placebo fixed effects regressions in which the labor law index in each state for 1904 is assigned to 1870, for 1909 to 1880, for 1914 to 1890, and for 1919 to 1900. The qualitative placebo results are quite different from the actual results. If there is selection bias, then it might well be working against the findings of the study.

There are some logical reasons to conclude that the results were not biased by endogeneity in the direction described in the analysis below. The results show that the dominant shift for the law index was the rise in labor supply. The endogeneity problem would arise if the increase in labor supply caused the state to increase the labor law index. One way this would have occurred is if the rise in the number of manufacturing workers gave the workers more voting power in state legislatures. But most of the increase in manufacturing labor supply in the USA through 1914 was driven by immigrants from poorer European countries. They generally did not have the vote, and discrimination by fellow workers would have weakened the political coalition pressing for reform. Thus, it seems more likely that the rise in labor supply represented a marginal benefit from a better regulatory climate.

Table 2 presents summary statistics, and the estimation results for the employment and earnings equations are presented in Table 3. The estimates of the demand and supply elasticities with respect to the regulatory climate are then presented in Table 4. The data come from a variety of sources. Manufacturing employment and earnings information comes from the 1904, 1909, 1914, and 1919 Manufacturing Censuses reported in the Statistical Abstract of the USA.Footnote 8 All dollar values are deflated by the Consumer Price Index with 1967 equal to 100 from US Bureau of the Census (1975 series E-135, pp. 210–11). The employment measure is the average number of workers employed by the firm per month, which is calculated as the sum of the number of workers in each month divided by 12.

Average annual earnings when divided by 12 are average monthly earnings because they are calculated as the total wage bill divided by average number of workers over the course of the year. In the analysis, we are treating annual earnings as the measure of the wage because the Census measures of annual earnings are the only measures of earnings consistently available across states during this period. Annual earnings are the right measure for salaried workers who were often paid by the month or year. They are also a valid measure of the wage for wage earners in the sense that they measure the income package available to the worker for the entire year, which was important in many industries that dealt with exogenous fluctuations in work opportunities within the year and across years. To the extent that fluctuations in hours worked during the year were determined by the workers’ own choices, the annual earnings reflect labor supply decisions and thus lead to some degree of measurement error when translating findings for employment and annual earnings into discussions of shifts in labor demand and supply.

The union index was developed by Fishback and Kantor (2000) using data from Whaples (1990b), Wolman (1936), and Troy (1965). It was calculated based on state employment information from the censuses and national union information by industry from Troy (1965) and Wolman (1936) for the years 1899, 1909, and 1919, with straight-line interpolations between those years. It measures the extent to which the industries in the state had strong unionization at the national level. The trend measures of percent black, percent foreign born, percent illiterate, and percent urban come from the population census via Haines’ (2012) ICPSR 2896 census state and county data sets and are based on straight-line interpolations between the census years 1900, 1910, and 1920 to obtain values for the years in the dataset.

6 Results for the law index

The results for wage workers in Tables 3 and 4 show a positive employment elasticity with respect to the law index and a negative or possibly zero earnings elasticity with respect to the laws. The possible combinations match the inferences in rows 1, 2, 3, and 7 in Table 1. In all four cases, both workers and employers ultimately gained from the regulation after the shifts in labor supply and labor demand. Further, the four cases suggest that workers received positive direct marginal benefits from the laws that were the same or larger than direct marginal benefits for employers or larger than the direct marginal costs to employers from the laws.

The positive relationship between wage workers’ employment and the law index is shown by the employment coefficients in specifications 1, 3, and 4 in Tables 3 and 4. In specifications 1 and 3, both law coefficients imply elasticities of wage worker employment with respect to the appropriations measure of 0.109, although neither coefficient is statistically significant. When an interaction term is incorporated in specification 4, however, the coefficients of the law and appropriations measures and their interaction are all statistically significant. The elasticity of employment with respect to the law index in Table 4 ranges from 0.068 when the appropriations measure is one standard deviation below its mean to 0.157 when the appropriations measures is at the mean to 0.247 when the appropriations measure is one standard deviation above its mean.

The earnings elasticity with respect to the law index is in the range of – 0.050 and – 0.086 in the various specifications in Tables 3 and 4, although the statistical significance of the coefficients varies. Without the appropriations variable in specification 1, the law coefficient implies an elasticity of earnings with respect to the law index of – 0.069 percent, which is statistically significant at the 10 percent level. The elasticity is – 0.09 when the appropriations variable is included in specification 3, but it is not statistically significant at better than the 10-percent level. When the interaction term is added in specification 4, the earnings elasticity with respect to the law index ranged from – 0.056 when the appropriations measures was one standard deviation below the mean to – 0.071 when the appropriations measure was at the mean to – 0.086 when the appropriations measure was one standard deviation above the mean. However, none of the coefficients of the law measure, the appropriations measures, or the interaction term are statistically significant; the p value for the F-test that all three coefficients were different from zero is 0.23.

In the final analysis, both workers and employers gained from increases in the law index. The workers gained because employment rose and the marginal value of the improvement in their working conditions more than outweighed the reduction in earnings. Meanwhile, the employers gained because the gain from paying lower wages for more workers more than offset the costs of complying with the regulations or possibly even gaining themselves some direct benefit from the legislation.

7 Results for labor appropriations per gainfully employed worker

The elasticities for the state labor appropriations per gainfully employed worker were substantially smaller than for the laws measure. The employment elasticity estimates in Table 4 were negative at – 0.037 when the law index was one standard deviation below the mean, 0.002 when it was at the mean, and 0.041 when the law index was one standard deviation above the mean. Thus, workers and employers both ultimately lost with higher appropriations in state-years when the law index was low, both experienced no change when the index was at the mean, and both ultimately gained when the index was high.

The earnings elasticity was negative in all settings, but the coefficient was only statistically significant in Table 3 in specification 2 when the law index was not included in the regulation. The combinations of the negative earnings elasticity with the varied elasticities for employment suggest that in state-years when the law index was low, the employers’ direct marginal cost from the appropriations was the dominant factor as in rows 8 through 10 in Table 1, that the employers’ direct marginal costs were the same as the workers’ direct marginal benefits when the law index was at the mean as in row 15, and that the workers’ direct marginal benefits outweighed any direct marginal costs or benefits for employers as in rows 1 through 3.

8 What can we learn from assuming earnings elasticities for labor demand and supply?

Thus far, we have been able to infer that increases in the law index benefited both workers and employers and the consequent rise in direct marginal benefits for workers was the same or larger than either the rise in employers’ marginal benefits or larger than the rise in employers’ marginal costs. The same can be said for appropriations when the law index was at its mean or higher. We are still uncertain about whether employers had direct marginal benefits or marginal costs from the regulations that would have shifted labor demand higher or lower. We can say more about the issue by making some assumptions about the earnings elasticity of labor demand and labor supply and using Eqs. 3a) and 3b) to develop estimates of the demand and supply elasticities with respect to the law index and the appropriations. We can also say more about the size of the labor supply shifts.

We use a broad range of labor demand elasticities and a broad range of labor supply elasticities because there are only a few estimates in the literature and they vary quite a bit. By doing so, we can check the robustness of the results to the different assumptions.Footnote 9 The literature on estimating demand elasticities shows a range from close to zero to around – 1.5 for various estimates of demand elasticities. We found only one estimate that was specific to manufacturing workers. Richard Freeman (1980, pp. 7, 18–19) estimated long run manufacturing labor demand elasticities of – 0.33 to – 0.6 using time series analysis with lagged values as instruments. Daniel Hamermesh’s (1993, 270–273) summary of demand elasticities for all males suggests that the demand is generally inelastic and the estimates range from 0 to – 1. Acemoglu et al. (2004) estimate that the demand elasticity for all women workers in the 1940s was more elastic and ranged between – 1 and – 1.5. Given our focus on manufacturing, which had more specific skill requirements than general labor demands, employers would have had fewer substitute workers from which to choose, making the manufacturing labor demand more inelastic than the demand for all workers as a category. Our best guess of the manufacturing labor demand elasticity is that it was in the – 0.5 to the – 1.0 range for production workers. Yet, there remains a great deal of uncertainty about the right elasticity to choose for each type of worker, particularly because we are also looking at salaried workers of both genders as well. As a result, we report labor demand changes for wage elasticities of – 0.3, – 1, and – 1.5 to more than cover the ranges we have seen in the literature.Footnote 10

The range of labor supply elasticities in the literature is much larger and there is a substantial debate (Keane and Rogerson 2012; Chetty et al. 2011). Part of the debate centers on differences in the level of aggregation in estimation. Studies of individual data often find small elasticities that are well below 1, while macroeconomists focusing on aggregate data for the whole labor force use elasticities ranging from 1 to 3. Keane and Rogerson (2012) argue that the small estimates from individual data imply the larger elasticities with aggregate data, but Chetty, et. al. (2011) still argue for aggregate elasticities below one. Neither the individual nor the macroelasticities fit the context we are examining exactly because the macroestimates are for the entire economy and the micro estimates are for individuals. The one set of estimates we found specific to manufacturing was Freeman’s (1984) long run estimates in the 5–6 range using time series analysis with lagged values as instrumental variables. The larger elasticity for manufacturing as opposed to all types of work makes sense because workers have more options outside of manufacturing. Based on intuition and our use of aggregated hours and employment and mean earnings, we expect the elasticity to be in the 3–5 range. Here again, we provide a broad range of estimates of 1, 3, and 5 for the reader to show the results for the broad range in the literature.

The results in Table 5 for the supply elasticities with respect to regulation reconfirm the inferences that we could make with the reduced form employment and earnings elasticities. The positive supply elasticities with respect to the law index show that workers experienced positive direct marginal gains from increases in the law indexes. With one exception, the situation was similar for increases in appropriations, although the smaller positive supply elasticities imply that the workers’ direct marginal benefits from appropriations were lower than for the law index. The size of the workers’ marginal benefits that we can infer are larger when the supply elasticity with respect to earnings is larger. The exception was a negative supply elasticity when the law index was one standard deviation or more below the mean, which implied a direct marginal cost rather than marginal benefit associated with the appropriations.

The mostly positive demand elasticities with respect to the law index in Table 5 specification 4 suggest that employers also experienced positive direct marginal benefits from expansions in the law index. The one exception occurred when the appropriations measure was one standard deviation below the mean and the elasticity was assumed to be elastic with a value of – 1.5. The demand elasticities with respect to appropriations were almost all negative or close to zero, implying that employers experienced higher marginal costs when the appropriations measures increased.

9 Demand and supply shifts with respect to the components of the law index

The labor law index is built up from several components: compensation for workplace accidents, factory regulations, child labor laws, women’s laws, the net measure of pro- and anti-union laws, anti-corruption laws, the presence of administrative bodies, and hours laws. Table 6 reports the coefficients of reduced form regressions for earnings and employment in which the labor law index is replaced by its components. Two of the labor law components have at least one statistically significant coefficient between the two equations. The employment elasticity with respect to the factory laws was statistically significant and positive at 0.038, yet the earnings elasticity was essentially zero, which is consistent with a situation in Table 1 row 7 where both employers and workers anticipated similar positive marginal benefits from the regulations, and both ultimately gained from the regulation. In the case of the net union law index, the employment elasticity was statistically significant and negative at – 0.071, while the earnings elasticity was – 0.029 but not statistically significant. The combination of the negative employment elasticity and a negative or zero earnings elasticity implies that employers faced a direct marginal cost that was the same or higher than any direct marginal benefit obtained by the workers, as in rows 8–10 or 15 in Table 1. The ultimate effect was for both workers and employers to lose from an increase in the net union laws, likely due to increases in the likelihood of strikes, which often hurt both parties.

If we focus only on reduced form employment and earnings coefficients and not statistical significance, the positive reduced form employment elasticities imply that both workers and employers ultimately gained from increases in the laws related to accident compensation, factory conditions, child labor, anti-coercion, and hours. In each case the earnings elasticity was negative, which suggests that the workers’ direct marginal benefit from the laws was higher than the direct marginal benefit or cost for employers, as in rows 1 through 3 in Table 1. The employment elasticity for laws regulating female work, net unionization, administration, and appropriations were all negative, which implied that workers and employers ultimately lost gains from trade when these laws were enacted. The negative reduced form earnings elasticity for the female, net union, and appropriations imply that the employers’ direct marginal cost was higher than the direct marginal benefits or marginal cost to workers.

More can be said about direct marginal benefits and direct marginal costs by calculating the regulation elasticities after making assumptions about the earnings elasticities for supply and demand. The elasticities in Table 5 suggest that workers and employers both had direct marginal benefits from regulations related to factories, children, anti-coercion, and hours. Employers had direct marginal costs and workers direct marginal benefits from regulations for women and the appropriations measures. Workers had direct marginal benefits and employers had either no or positive direct marginal benefits from accident compensation regulations. The net union laws imposed direct marginal costs on employers, while workers had direct marginal costs if the earnings supply elasticity was 1, but direct marginal benefits if the earnings supply elasticity was 3 or higher. Finally, workers and employers both faced direct marginal costs from the administrative laws.

10 Salaried workers

The discussion so far has focused on the workers paid wages who tended to work on the production lines. We also have information on the employment and salaries of salaried workers. A priori, we expected the introduction of labor legislation would impact salaried workers by increasing supervision requirements, particularly in cases where safety laws required increased monitoring, and the extent of paperwork involved in reporting information to state authorities. Thus, we predicted a rise in the demand for salaried workers with positive elasticities for salaries and employment, which would have implied ultimate gains for both salaried workers and employers; however, we did not find evidence consistent with this prediction.

11 Conclusions

We add to the understanding of Progressive Era labor regulations and their impact on manufacturing workers and employers. Our analysis considers a wide range of possible implications from the laws and then uses fixed effects estimations to quantify the direct gains from the laws and who paid direct marginal costs for the laws. Ultimately, we find gains accrued to both wage earners and employers as a result of increased employment. Specifically, the regulatory changes provided for a better employment package for workers and lower costs of providing the package for employers. The key to this finding is that in situations where the regulation stimulates employment, either the workers and employers both have direct marginal benefits, the workers’ direct marginal benefit exceeds the employers’ direct marginal cost, or the employers’ direct marginal benefit is greater than the workers’ direct marginal cost.

We collected data on manufacturing annual earnings and employment by state for the years 1904, 1909, 1914, and 1919 from the US manufacturing censuses. We combined this information with an index of labor laws and appropriations per gainfully employed worker for each state in the year preceding these observations. We then used the data to estimate reduced form elasticities for earnings and employment with respect to the labor regulations measures.

The results show that workers and employers both ultimately gained from expansions in the labor law index because the reduced form employment elasticity with respect to the law index was positive. When that result is combined with a zero or negative earnings elasticity with respect to the law, we can infer that workers received a direct marginal benefit from the law that was larger than direct marginal benefits or marginal costs to employers. After assuming a broad range of labor demand elasticities with respect to earnings, we can infer that employers likely also received direct marginal benefits from the laws.

The situation for appropriations per gainfully employed worker was more complex and depended on the size of the labor law index. The employment elasticity with respect to appropriations was negative in state-years with low labor law indices, implying that both workers and employers ultimately lost from the introduction of the appropriations. The employment elasticity was essentially zero in state years when the labor law index was at its mean, which implied that the appropriations had no impact on the ultimate gains and losses for workers and employers. In state years when the labor law index was high, the employment elasticity was positive and both workers and employers ultimately gained from increases in the appropriations measure. After making assumptions about supply and demand elasticities with respect to earnings, workers likely received marginal benefits from the appropriations while employers generally paid marginal costs except when the labor law index was high.

The quantitative literature on state labor laws includes a variety of studies that isolate the impacts of specific laws. In contrast, we examine a wide range of labor laws that have not been broadly studied, and the cumulative weight of the laws collectively extend beyond just the sum of the parts. The results here suggest that labor reformers succeeded at improving overall working conditions for workers and it is likely that employers benefited as well. Some of the specific laws might not have had such positive effects. Yet, labor legislation as a whole during the early 1900s was a win–win proposition for many manufacturing employers and workers.

Notes

For example, see Moehling (1999), Sanderson (1974), Osterman (1979), Brown et al. (1992), and Carter and Sutch (1996) on child labor, Goldin (1990) and Whaples (1990a, 1990b) on women’s hours laws, Fishback and Kantor (2000), Buffum (1992), Chelius (1976, 1977), Fishback (1986, 1987, 1998), and Aldrich (1997) on workers’ compensation and employer liability laws, Fishback (1986, 1992, 2008) on coal mining regulations, Aldrich (1997) on safety regulations in manufacturing, mines, and railroads, Fishback (2020) on union and collective bargaining laws and strikes and violence, and Marchingiglio and Poyker (2020) on women’s minimum wages and employment. For a summary of the research, see Fishback (1998). Moehling (1999) finds that child labor legislation had little impact on employment of children, but Clay et al. (2012), Margo and Finegan (1996) and Lleras-Muney (2002) find that school attendance laws raised school attendance and increased average years of schooling.

Many of the studies of specific labor laws did not control for the presence of other labor laws, and thus, their estimates of the impact will be subject to omitted variable bias to the extent that the specific laws were correlated with the overall labor regulation climate.

When we extend the discussion outside the borders of a single state, many employers argued against labor legislation in their own state on the grounds that they would be placed at a competitive disadvantage with respect to employers in other states (Moss 1996). The inter-state argument can extend to private contracting by firms within states.

The logic reported here is similar to the analyses of marginal taxes and marginal subsidies seen in most microeconomics textbooks.

Some of the regulations might provide both benefits and costs to a group. In that case we would be talking about the marginal net benefit to the group.

We also calculated the index using the state employment weights. The estimation results were very similar to the results using the national employment weights that we discuss in the text.

We explored the use of two different types of instruments but both instruments lacked strength. The first instrument involved creating a Progressive Law Index that ranged from 0 to 6 based on whether the state had laws in each of six categories: initiative and referendum laws, direct primaries, state tax commissions, state welfare agencies, merit systems for their state workers, and regulations of electric utilities (Nonnenmacher 2002; Walker 1969). The second was similar to a Bartik instrument. Using the labor law index for 1899, we calculated the ratio of the state index to the national average in 1899. We then multiplied the 1899 ratio times the national average law index for each of the years in the data set to get an estimate of the state labor index for those years.

The discussion in this and the next paragraph is borrowed from Shatnawi and Fishback (2018).

Note that in the labor Demand Eq. 1a) in the text, there is a minus sign in front of the wage coefficient a1, so that in the derivations of the relationships in the remaining equations, a1 would have positive values 0.3, 1, and 1.5.

References

Acemoglu D, Autor DH, Lyle D (2004) Women, war, and wages: the effect of female labor supply on the wage structure at midcentury. J Polit Econ 112(3):497–551

Aldrich M (1997) Safety first: technology, labor, and business in the building of american work safety, 1870–1939. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Becker G (1983) A theory of competition among pressure groups for political influence. Quart J Econ 98:371–400

Brown M, Christiansen J, Philips P (1992) The Decline of Child Labor in the U.S. fruit and vegetable canning industry: law or economics? Bus Hist Rev 66(4):723–770

Buenker JD, Burnham JC, Crunden RM (1977) Progressivism. Schenkman Publishing Company, Inc., Cambridge, MA

Buffum D (1992) Workmen’s compensation: passage and impact. Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania

Carter SB, Sutch R (1996) Fixing the facts: editing of the 1880 U.S. census of occupations with implications for long-term labor force trends and the sociology of official statistics. Hist Method 29(1):5–24

Chelius JR (1976) Liability for industrial accidents: a comparison of negligence and strict liability systems. J Leg Stud 5(2):293–309

Chelius JR (1977) Workplace safety and health: the role of workers’ compensation. American Enterprise Institute, Washington, DC

Chetty R, Guren A, Manoli D, Weber A (2011) Are micro and macro labor supply elasticities consistent? A review of evidence on the intensive and extensive margins. Am Econ Rev 101(3):471–475

Clay K, Lingwall J, Stephens M (2012) Do school laws matter? Evidence from the introduction of compulsory attendance laws in the United States Cambridge, MA: national bureau of economic research working paper No. 18477

Commons JR, Associates (1966) History of Labor in the United States, 4 volumes, reprint of material published between 1916 and 1935. Augustus Kelley Publishers, New York

Fishback PV (1986) Workplace safety during the progressive era: fatal accidents in bituminous coal mining, 1912–1923. Explor Econ Hist 23(3):269–298

Fishback PV (1987) Liability rules and accident prevention in the workplace: empirical evidence from the early twentieth century. J Leg Stud 16(2):305–328

Fishback PV (1998) Operations of “unfettered” labor markets: exit and voice in American labor markets at the turn of the century. J Econ Lit 36:722–765

Fishback PV, Kantor SE (1992) “Square Deal” or raw deal? Market compensation for workplace disamenities, 1884–1903. J Econ Hist 52(4):826–848

Fishback PV, Kantor SE (2000) A prelude to the welfare state: the origins of workers’ compensation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Fishback PV, Coal S, Choices H (1992) The economic welfare of bituminous coal miners, 1890–1930. Oxford University Press, New York

Fishback PV, Holmes R, Allen S (2009) Lifting the curse of dimensionality: measures of the labor legislation climate in the states during the progressive era. Labor Hist 50(3):313–346

Fishback PV (2008) The progressive era the period between the mid-1890s and the early 1920s has been enshrined as the progressive era. It was truly. Government and the American economy: a new history pp 288

Fishback PV (2020) Rule of law in labor relations, 1898–1940. Cambridge, MA: national bureau of economic research working paper

Freeman RB (1980) Unionism and the dispersion of wages. ILR Rev 34(1):3–23

Freeman RB (1984) Longitudinal analyses of the effects of trade unions. J Law Econ 2(1):1–26

Goldin C (1990) Understanding the gender gap: an economic history of women. Oxford University Press, New York

Gould L (ed) (1974) The progressive era. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, NY

Haines MR. Historical, demographic, economic, and social data: the United States, 1790–2000. Inter-university consortium for political and social research

Hamermesh D (1993) Labor demand. Princeton University Press Princeton, New Jersey

Hofstadter R (1955) The age of reform: from bryan to F.D.R. Alfred A. Knopf, New York

Holmes R (2003) The impact of state labor regulations on manufacturing input demand during the progressive era Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Arizona Economics Department

Keane M, Rogerson R (2012) Micro and macro labor supply elasticities: a reassessment of conventional wisdom. J Econ Lit 50(2):464–476

Kolko G (1963) The triumph of conservatism: a reinterpretation of American history, 1900–1916. Free Press, New York

Lleras-Muney A (2002) Were compulsory attendance and child labor laws effective? An analysis from 1915–1939. J Law Econ 45:401–435

Lubove R (1967) Workers’ compensation and the prerogatives of voluntarism”. Labor Hist 8(Fall 1967):227–254

Lubove R (1968) The struggle for social security: 1900–1935. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Marchingiglio R, Poyker M (2020) The economics of gender-specific minimum-wage legislation. Unpublished working paper, Northwestern and Columbia Universities

Margo R, Finegan A (1996) Compulsory schooling legislation and school attendance in turn of the century America: a natural experiment approach. Econ Lett 53(1):103–110

Moehling C (1999) State child labor laws and the decline of child labor. Explor Econ Hist 36:72–106

Moss D (1996) Socializing security: progressive-era economists and the origins of american social policy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nonnenmacher T (2002) Patterns of reform and regulation in the states: 1880–1940. Unpublished working paper. Allegheny college

Osterman P (1979) Education and labor markets at the turn of the century. Polit Soc 9(1):103–122

Pelzman S (1976) Toward a more general theory of regulation. J Law Econ 19:211–248

Sanderson A (1974) Child-labor legislation and the labor force participation of children. J Econ Hist 34(1):297–299

Shatnawi D, Fishback P (2018) The impact of World War II on the demand for female workers in manufacturing. J Econ Hist 78(2):539–574

Skocpol T (1992) Protecting soldiers and mothers: the political origins of social policy in the United States. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Stigler G (1971) The theory of economic regulation. Bell J Econ Manag Sci 2:3–21

Troy L (1965) Trade union membership 1897–1962. National bureau of economic research occasional paper No. 92. Columbia University Press, New York

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (1914) Labor laws of the United States, with decisions of courts relating thereto. Bulletin of the United States bureau of labor statistics No. 148. 2 parts. Washington: GPO

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (1925) Labor laws of the United States, with decisions of courts relating thereto. Bulletin of the United States bureau of labor statistics No. 370. Washington: GPO

U.S. Bureau of the Census (1975) Historical statistics of the United States, 1790–1970. Government Printing Office, Washington

U.S. Commissioner of Labor (1896) Labor laws of the United States second special report of the commissioner of labor. Washington: GPO

U.S. Commissioner of Labor (1904) Labor laws of the United States with decisions of courts relating thereto. Tenth special report of the commissioner of labor. Washington: GPO

U.S. Commissioner of Labor (1907) Labor laws of the United States with decisions of courts relating thereto, 1907. Twenty-second annual report of the commissioner of labor. Washington: GPO

U.S. Department of Commerce (1914) Statistical abstract of the United States, 1913, thirty-six number. Government Printing Office, Washington

U.S. Department of Commerce (1925) Statistical abstract of the United States 1924 forty-sixth number, Washington DC: Government Printing Office

Walker J (1969) The diffusion of innovations among the American States. Am Politi Sci Rev 63:880–899

Weinstein J (1967) Big business and the origins of workmens’ compensation. Lab Hist 8:156–174

Whaples R (1990a) Winning the eight-hour day, 1909–1919. J Econ Hist 50(2):393–406

Whaples R (1990b) The shortening of the American work week: an economic and historical analysis of its context, causes, and consequences, PhD. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania

Wiebe R (1962) Businessmen and reform: a study of the progressive movement. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Witte E. The government in labor disputes. New York: Arno and the New York Times, 1969

Wolman L (1936) The ebb and flow of trade unionism. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, S.K., Fishback, P.V. & Holmes, R. The impact of progressive era labor regulations on annual earnings and employment in manufacturing in the USA, 1904–1919. Cliometrica (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-024-00287-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-024-00287-2