Abstract

Purpose

Research suggests that internalised weight stigma may explain the relationship between perceived weight stigma and adverse psychological correlates (e.g. depression, disordered eating, body image disturbances). However, few studies have assessed this mechanism in individuals seeking bariatric surgery, even though depression and disordered eating are more common in this group than the general population.

Materials and Methods

We used data from a cross-sectional study with individuals seeking bariatric surgery (n = 217; 73.6% female) from Melbourne, Australia. Participants (Mage = 44.1 years, SD = 11.9; MBMI = 43.1, SD = 7.9) completed a battery of self-report measures on weight stigma and biopsychosocial variables, prior to their procedures. Bias-corrected bootstrapped mediations were used to test the mediating role of internalised weight stigma. Significance thresholds were statistically corrected to reduce the risk of Type I error due to the large number of mediation tests conducted.

Results

Controlling for BMI, internalised weight stigma mediated the relationship between perceived weight stigma and psychological quality of life, symptoms of depression and anxiety, stress, adverse coping behaviours, self-esteem, exercise avoidance, some disordered eating measures and body image subscales, but not physical quality of life or pain.

Conclusion

Although the findings are cross-sectional, they are mostly consistent with previous research in other cohorts and provide partial support for theoretical models of weight stigma. Interventions addressing internalised weight stigma may be a useful tool for clinicians to reduce the negative correlates associated with weight stigma.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Weight stigma is the pervasive social devaluation enacted towards individuals because of their weight [1]. Individuals living with higher weight report experiencing weight stigma between one and six times per week [2,3,4]. From the perspective of these individuals, weight stigma can manifest as stigma (a) experiences (e.g. being called names), (b) perceptions (e.g. feeling like others are staring at you), (c) internalisation (i.e. where individuals apply negative stereotypes about weight to themselves resulting in self-devaluation—e.g. believing you are not worthy of love or a job), and (d) anticipation (e.g. expecting poor treatment from others) [5,6,7]. A recent meta-analysis found a significant moderate association between public (i.e. perceived and experienced; k = 241) weight stigma and internalised weight stigma (k = 222) and adverse psychological health [8]. Research has found these associations across community, clinical, and student cohorts, and also in bariatric surgery patients and individuals seeking bariatric surgery [9, 10].

Meta-analytic evidence indicates that depression and binge eating disorder are more common in bariatric surgery patients and individuals seeking bariatric surgery compared to the general population [11]. Moreover, cross-sectional studies with individuals seeking bariatric surgery have found that experienced weight stigma is associated with emotional eating, body shame, internalised shame, and lower self-compassion [12], and that internalised weight stigma is associated with depression, anxiety, and poor quality of life and self-esteem [13]. However, the precise mechanism(s) through which weight stigma is associated with adverse correlates in this population has been understudied.

Some scholars have suggested the extent to which individuals internalise weight stigma mediates the relationships between experienced/perceived weight stigma and psychosocial correlates [14, 15]. A recent systematic review [16] indicated only one paper had assessed this mechanism in individuals seeking bariatric surgery, with mixed results [17]. Internalised weight stigma did not significantly mediate the relationship between experienced weight stigma and depression or anxiety when measured as the sole mediator. However, it was a significant mediator in models that also included other mediators such as body shame, internalised shame, and self-compassion. Thus, given the observed differences between bariatric surgery populations and the general population [11], there is a need to further investigate the mechanisms underpinning the relationship between weight stigma and psychosocial correlates in individuals seeking bariatric surgery, with a specific focus on internalised weight stigma as a mediator. Identifying the mechanisms through which weight stigma is associated with adverse correlates may provide support to existing theoretical models from which targeted clinical interventions can be developed and implemented as part of routine pre and post bariatric surgery care.

The aims of the current study were to estimate (a) the relationship between both perceived and internalised weight stigma, and psychosocial and physical correlates, and (b) the indirect effect of perceived weight stigma on the relationship between psychosocial and physical health correlates, via internalised weight stigma [14]. Based on previous research [8], we expected to find (a) a positive correlation between perceived and internalised weight stigma, (b) correlations between perceived and internalised weight stigma and negative psychosocial correlates (e.g. higher levels of depression, lower levels of quality of life), and (c) that internalised weight stigma would mediate the relationship between perceived weight stigma and psychosocial correlates [16]. Lastly, we made no prediction regarding physical health correlates, as research on physical health correlates in this domain is, at present, exploratory.

Method

Participants

Participants (n = 217; 73.6% female) were recruited prior to their procedures between 2014 and 2015 from a private bariatric surgery clinic located in Melbourne, Australia (Mage = 44.1 years, SD = 11.9; MBMI (kg/m2) = 43.1, SD = 7.9). They were informed that participating would not affect their status as individuals seeking bariatric surgery. This was a cross-sectional study—all 217 participants in the current study were a subset of a larger study that completed weight stigma questionnaires, which were introduced after data collection began. Findings from this larger study have been published elsewhere [18]. As part of their consent, participants agreed to allow their non-identifiable, aggregated data to be used in future projects. Unfortunately, we do not have access to intake data that shows the number of individuals who were asked to participate but chose not to.

Measures

Weight Stigma, Quality of Life, Disordered Eating, Body Image, Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety, and Other Biopsychosocial Measures

Table 1 shows all the measures used in the current study (excluding demographics). These include a perceived weight stigma scale, an internalised weight stigma scale, and a total of 16 psychosocial correlate scales. Some of the psychosocial correlate scales produce scores for subscales (total number of psychosocial correlate variables in the study is 51). For more detailed information on the scales, including descriptions, sample items, and reliability estimates, see the Measures section and Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

Demographics

Participants were asked a series of demographic questions. These included questions asking participants’ age, sex, height and weight (for BMI), and birth country (see Table 2).

Procedure

Monash University’s Human Research Ethics Committee approved this research (CF11/0309 – 2011000106). Individuals seeking bariatric surgery were invited to participate by completing a pre-operative intake questionnaire. Participants completed the questionnaire in their own time and were provided with a postage paid envelope to return to the clinic when completed.

Data Analysis Plan

Data cleaning and screening information can be found in the Supplementary Material. Of the 214 participants, 205 had complete data on measures of perceived and internalised weight stigma (see Table 1). The number of valid cases for our mediation analyses ranged between 198 and 205, depending on the psychosocial variable measured. First, we obtained descriptive statistics for all variables and conducted reliability analyses on all measures in SPSS [38]. Then, we obtained estimates of the bivariate relationships between perceived and internalised weight stigma, and psychosocial and physical correlates. Next, assumptions were checked. Although scores on the POTS were positively skewed, parametric tests are robust to violations of normality in large sample sizes [39, 40]. Leverage values did exceed the critical regions in most variables by 0.005–0.010; however, other similar metrics (e.g. Mahalanobis distance, Cook’s, DFBETAS, DFFITS) did not identify any influential cases. The data were then transferred to jamovi [41], where 51 separate bias-corrected bootstrapped mediations (5000 resamples) were run, with perceived weight stigma (POTS) as the predictor, the internalised weight stigma (WBIS) as the mediator, and each of the psychosocial variables listed above as the outcome variables. In all these analyses, we controlled for BMI.

Correction to Reduce the Risk of Type I Error

The large number of mediation tests (i.e. 51) raise concerns about the probability of Type I errors. There is much debate about family-wise error rate, the types of corrections available, and the appropriateness and effectiveness of such corrections [42,43,44,45]. This is partly due to the difficulty of estimating the degree of dependence between the different tests conducted on the same data set. Based on a reviewer’s recommendation, we implemented the Hochberg procedure (see Cao and Zhang) [46]. We did this after classifying the variables into relevant conceptual domains (i.e. disordered eating, psychological quality of life, physical quality of life and health, body image, and psychological distress/functioning variables). A complete list of this procedure being applied to these different domains in our data can be found in Table S2.

Results

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for the demographics of the current sample. Due to the large number of measures in the current study, means, standard deviations, and internal consistency scores for all non-demographic measures used are presented in Table S1. In sum, perceived weight stigma was positively associated with negative correlates such as disordered eating, symptoms of depression and anxiety, stress, and pain except for EDE-Q restraint, DEBQ restraint, DEBQ emotional eating, QEWP, WEL restraint, AQoL pain, and several MBSRQ subscales. Perceived weight stigma was also negatively associated with positive correlates, such as quality of life, motivation to exercise, and self-esteem (see Table S3 for full list of correlations of all psychosocial and physical correlate variables with perceived and internalised weight stigma, and BMI). Similar relationships were found between internalised weight stigma and these biopsychosocial correlates.

Mediations

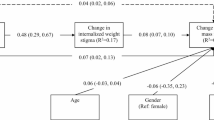

Mediation analyses were conducted to estimate the indirect effect of perceived weight stigma on psychosocial correlates via internalised weight stigma, after controlling for BMI (see Fig. 1). Correlates were separated into three conceptual domains: eating behaviour, quality of life and physical health, and other psychosocial health correlates.

Tables 3, 4, and 5 present the mediation analyses results for each of these domains. The tables report the unstandardised and standardised effect size estimates and standard errors for the total effect (c), direct effect (cʹ), the individual predictor-mediator (a) and mediator-outcome (b) pathways, and the indirect effect (a*b) with confidence intervals and its corresponding p value. Importantly, bolded variables in Tables 3, 4, and 5 indicate the mediation was significant after correcting to reduce the risk of Type I error with the Hochberg procedure. Note that some measures had confidence intervals that did not include zero (e.g. EDEQ-R, QEWP), indicating an effect; however, these p values did not meet the threshold for significance after the Hochberg procedure.

Disordered Eating Variables

Internalised weight stigma mediated the relationship between perceived weight stigma and some disordered eating measures (i.e. 6 of 14 measures were significant after correcting to reduce the risk of Type I error, including measures of emotional eating, eating-specific psychosocial impairment, and shape and weight concern). One measure of disinhibition was significant and one was not significant. All measures of dietary restriction/restraint were non-significant, as were external eating, hunger, and eating concern (see Table 3).

Quality of Life and Physical Health Variables

Internalised weight stigma mediated the relationship between perceived weight stigma and all measures of psychological quality of life, but not physical quality of life or pain (see Table 4).

Other Psychosocial Variables

Internalised weight stigma mediated the relationship between perceived weight stigma and symptoms of depression and anxiety, exercise avoidance, maladaptive responses to intense negative mood states (general and eating specific), self-esteem, and 5 of 10 body image subscales (see Table 5).

Across all analyses, all significant relationships were in the expected direction. Specifically, higher perceived weight stigma was associated with higher internalised weight stigma, which was in turn associated with more adverse scores in the correlates (i.e. higher symptoms of anxiety, and lower psychological quality of life).

Discussion

The current study aimed to (a) assess the bivariate relationship between perceived and internalised weight stigma and psychosocial and physical correlates in individuals seeking bariatric surgery, and (b) estimate the mediating role of internalised weight stigma on the relationships between perceived stigma and said correlates [14]. All mediations were corrected to reduce the risk of Type I error. As expected, perceived and internalised weight stigma were significantly, positively correlated. Furthermore, both types of stigma were significantly associated with negative correlates (e.g. higher disordered eating and symptoms of depression, and lower quality of life), with a few exceptions.

We also found statistical evidence of the mediating role of internalised weight stigma on the relationship between perceived weight stigma and several psychological correlates, after controlling for BMI. These mediations were all in the expected direction, where higher perceived stigma is associated with higher internalised stigma, which in turn is associated with more negative outcomes. However, several estimated mediations were not significant for (a) some measures of disordered eating, including external eating and all measures of restraint, (b) some measures of body image, and (c) all measures of physical health, specifically, physical quality of life and pain.

Our mediation findings are consistent with those in other populations (e.g. university students, community and clinical participants), where internalised weight stigma was found to mediate the relationship between perceived weight stigma and psychosocial correlates, after controlling for BMI [47,48,49,50,51,52]. Moreover, our findings extend previous research conducted with individuals seeking bariatric surgery, by assessing a number of new psychosocial correlates beyond depression and anxiety [17]. Our study is the first to estimate this mediation effect in other correlates, such quality of life and disordered eating.

Though cross-sectional, our findings provide partial support to Tylka et al.’s [14] model of the role of internalised weight stigma. Specifically, internalised weight stigma mediated the relationship between perceived weight stigma and psychological well-being, as indicated above. However, internalised weight stigma did not mediate the relationship between perceived weight stigma and physical health correlates (i.e. pain and physical quality of life) and some disordered eating and body image measures, at least in this sample of individuals seeking bariatric surgery.

Research suggests weight stigma is linked to several poor physiological health correlates [53] and may partially explain the relationship between BMI and physiological health [54]. However, the physical quality of life measures used in this study make specific reference to issues associated with mobility and/or environmental barriers. Items from the AQoL, for example, ask: ‘How much help do you need with jobs around the house (e.g., preparing food, cleaning the house or gardening)?’ and ‘Thinking about how easy or difficult it is for you to get around by yourself outside your house (e.g., shopping, visiting)’. Variance in these types of correlates may be better explained by other more physical factors (e.g. ability, fitness, or weight) instead of weight stigma. Table S3 shows that in our sample, BMI was itself significantly negatively correlated with three of four physical quality of life measures across two subscales (senses subscale non-significant).

We also found non-significant findings for the pain correlates. Interestingly, Table S3 shows the observed correlation between BMI and pain was significant and positive for the pain severity subscale, but non-significant for pain interference. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between physical quality of life and pain on one hand, and physiological health and physical impairment on the other, as we found weight stigma is not associated with the former but a substantial amount of previous research has found weight stigma is associated with the latter.

Disordered Eating Correlates

We had mixed findings on disordered eating correlates. Specifically, internalised weight stigma did not mediate the relationship between perceived weight stigma and dietary restriction/restraint after correcting to reduce the risk of Type I error. Interestingly, although a systematic review found disordered eating correlates have been the most studied measure for this mechanism in the literature [16], restraint was measured only in three of the eight studies focusing on disordered eating. Two of these studies reported significant mediation for restraint, but this research was not conducted with bariatric surgery samples. The evidence for dietary restriction/restraint as a correlate of weight stigma is not only less well known than other measures of disordered eating but also inconclusive at present. Thus, additional studies looking at the present mediation pathway for restraint will be needed to estimate the size of the effect (or to determine if it is indeed zero).

As mentioned above, internalised weight stigma did not mediate the relationship between perceived weight stigma and external eating, eating concern, and hunger. We could see no obvious explanation for these non-significant findings. However, the difference in significant and non-significant disordered eating findings may have to do with the relative strength of emotion associated with each type of disordered eating. Specifically, it may be that restraint and external eating (i.e. intentions or thoughts about eating) are less distressing or pronounced for individuals than emotional eating and disinhibition, which are often accompanied by strong feelings of distress (as are shape and weight concern; see Table 3). Previous research has shown that both emotional eating and disinhibition are positively associated with distress [55, 56]. This may in part explain why we found significant indirect effects for the latter measures (with one exception) but not the former. Lastly, we could find no obvious explanation for the significant versus non-significant findings in the body image subscales.

Estimating Effect Size in Mediation Models

Reporting appropriate and meaningful estimates of effect sizes for mediation is a complex topic [57, 58]. As Wen and Fan [57] state, ‘no single index appears to be a viable mediation effect size measure’ (p. 199). They recommend reporting both the standardised and unstandardised total, and direct and indirect effects to estimate the effect sizes of the mediation, which we have done here. In the current study, many of the standardised effect size estimates for the indirect pathways we found for psychosocial correlates (i.e. the expected mediations) appear small (most were < 0.20). However, these expected mediations had a strong theoretical explanation, and these estimates were not trivial, with a few exceptions. Physical health measures (i.e. the exploratory mediations) were all non-significant, and in these cases, effect sizes were miniscule and were not close to significance. Thus, we can be somewhat more confident that these estimated mediations are genuine effects given the consistency of the findings.

Limitations of the Current Study and Future Research

Given the cross-sectional nature of the evidence presented here, our findings provide necessary but not sufficient evidence to support the causal pathways in the model. Future research should consider conducting longitudinal studies on the mediating role of internalised weight stigma to further clarify this mechanism, as experimental studies in this domain (i.e. exposing individuals to experiences of weight stigma) pose several ethical issues. Future research should also consider the complexities in the possible bi-directional relationships between the different types of weight stigma. For example, it might be useful to have clarity on whether individuals high in internalised weight stigma are more sensitive to, or have a lower threshold for, experiences and perceptions of weight stigma that occur in the environment.

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of the psychometric limitations of the Weight Bias Internalisation Scale [59]. This scale has demonstrated adequate to good psychometric properties in the current study, previous research with samples of community participants [60], and individuals seeking bariatric surgery [13]. It is also the most frequently used measure of internalised weight stigma in the literature, making it comparable to previous research. However, some recent evidence indicates that this scale may be confounded by other known predictors of disordered eating, such as body image and self-esteem (see Meadows and Higgs) [61]. Although this consideration is outside the scope of the current paper, a discussion of this issue can be found elsewhere [16, 62, 63].

Implications and Conclusion

As we have made clear elsewhere [16], ours and others’ suggestion to address the internalisation of weight stigma does in no way imply that the target of stigma is at fault or to blame for having internalised it. Indeed, internalisation of weight stigma, like internalisation of the thin ideal, would not exist in a world in which weight stigma was not the norm. We strongly advocate for the elimination of weight stigma in society. However, whilst cultural and societal changes are being enacted to eliminate weight stigma (which is likely to take many years), breaking the link between perceived and internalised weight stigma may help mitigate negative correlates in the shorter term. There is some evidence of interventions that may successfully decrease internalised weight stigma [64, 65].

Our results add support to previous findings highlighting the importance of including psychological components as part of a multi-disciplinary approach to clients’ care both before and after bariatric surgery [66, 67]. The fact that the relationships reported in this paper are present after controlling for BMI suggests that some of the negative correlates observed could be maintained even in the presence of surgical weight loss. Thus, interventions that address internalised weight stigma may improve patient outcomes beyond weight loss alone, and could be implemented by healthcare professionals as part of long-term care [64, 68, 69]. Such interventions would likely include psychoeducation about weight science and its complexities, challenging oversimplifications about weight and health, and cognitive restructuring and reappraisal, amongst many other things.

References

Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(12):788–805.

Vartanian LR, Pinkus RT, Smyth JM. Experiences of weight stigma in everyday life: implications for health motivation. Stigma Health. 2018;3(2):85.

Mallett RK, Swim JK. Bring it on: proactive coping with discrimination. Motiv Emot. 2005;29(4):407–37.

Potter L, Meadows A, Smyth J. Experiences of weight stigma in everyday life: an ecological momentary assessment study. J Health Psychol. 2020;1359105320934179.

Papadopoulos S, Brennan L. Correlates of weight stigma in adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic literature review. Obesity. 2015;23(9):1743–60.

Papadopoulos S, de la Piedad GX, Brennan L. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of self-reported weight stigma measures: a systematic literature review. Obes Rev. 2021;22(8):e13267.

Hunger JM, Dodd DR, Smith AR. Weight discrimination, anticipated weight stigma, and disordered eating. Eat Behav. 2020;37:101383.

Emmer C, Bosnjak M, Mata J. The association between weight stigma and mental health: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020;21(1):e12935.

Rosenberger PH, Henderson KE, Bell RL, Grilo CM. Associations of weight-based teasing history and current eating disorder features and psychological functioning in bariatric surgery patients. Obes Surg. 2007;17(4):470–7.

Myers A, Rosen JC. Obesity stigmatization and coping: relation to mental health symptoms, body image, and self-esteem. Int J Obes. 1999;23(3):221–30.

Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, Booth MJ, Miake-Lye I, Beroes JM, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):150–63.

Braun TD, Gorin AA, Puhl RM, Stone A, Quinn DM, Ferrand J, et al. Shame and self-compassion as risk and protective mechanisms of the internalized weight bias and emotional eating link in individuals seeking bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2021;1–11.

Hübner C, Schmidt R, Selle J, Köhler H, Müller A, de Zwaan M, et al. Comparing self-report measures of internalized weight stigma: the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire versus the Weight Bias Internalization Scale. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0165566.

Tylka TL, Annunziato RA, Burgard D, Daníelsdóttir S, Shuman E, Davis C, et al. The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. J Obes. 2014;2014.

Magallares A, Bolaños-Rios P, Ruiz-Prieto I, de Valle PB, Irles JA, Jáuregui-Lobera I. The mediational effect of weight self-stigma in the relationship between blatant and subtle discrimination and depression and anxiety. Spanish J Psychol. 2017;20.

Bidstrup H, Brennan L, Kaufmann L, de la Piedad Garcia X. Internalised weight stigma as a mediator of the relationship between experienced/perceived weight stigma and biopsychosocial outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Obes. 2021;1–9.

Braun TD, Quinn DM, Stone A, Gorin AA, Ferrand J, Puhl RM, et al. Weight bias, shame, and self-compassion: risk/protective mechanisms of depression and anxiety in prebariatic surgery patients. Obesity. 2020;28(10):1974–83.

Parker K, Mitchell S, O’Brien P, Brennan L. Psychometric evaluation of disordered eating measures in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2016;26(3):563–75.

Thompson JK, Cattarin J, Fowler B, Fisher E. The Perception of Teasing Scale (POTS): a revision and extension of the Physical Appearance Related Teasing Scale (PARTS). J Pers Assess. 1995;65(1):146–57.

Pearl RL, Puhl RM. Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale. Body Image. 2014;11(1):89–92.

Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders: Guilford Press; 2008.

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16(4):363–70.

Van Strien T, Frijters JE, Bergers GP, Defares PB. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord. 1986;5(2):295–315.

Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):71–83.

Bohn K, Fairburn CG. The clinical impairment assessment questionnaire (CIA). Cogn Behav Ther Eat Disord. 2008;315–7.

Spitzer R, Yanovski S, Marcus M. The questionnaire on eating and weight patterns-revised (QEWP-R). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1993.

Clark MM, Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Eaton CA, Rossi JS. Self-efficacy in weight management. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(5):739.

Vartanian LR, Shaprow JG. Effects of weight stigma on exercise motivation and behavior: a preliminary investigation among college-aged females. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(1):131–8.

Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R. The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(3):209–24.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD. Psychometric evaluation of the impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite questionnaire (IWQOL-Lite) in a community sample. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(2):157–71.

Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–43.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Allen KL, McLean NJ, Byrne SM. Evaluation of a new measure of mood intolerance, the Tolerance of Mood States Scale (TOMS): psychometric properties and associations with eating disorder symptoms. Eat Behav. 2012;13(4):326–34.

Rosenberg M. Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSE). Acceptance Commitment Ther Measures Packag. 1965;61(52):18.

Cash TF. Multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire: MBSRQ user’s manual. Norfolk, VA: Old Dominion University; 2000.

Cleeland CS, Ryan K. The brief pain inventory. Pain Res Group. 1991;143–7.

Nie NH, Bent DH, Hull CH. SPSS: Statistical package for the social sciences: McGraw-Hill New York; 1975.

Pett MA. Nonparametric statistics for health care research: statistics for small samples and unusual distributions: Sage Publications; 2015.

Fagerland MW. t-tests, non-parametric tests, and large studies—a paradox of statistical practice? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):1–7.

Şahin MD, Aybek EC. Jamovi: an easy to use statistical software for the social scientists. Int J Assess Tools Educ. 2019;6(4):670–92.

Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;65–70.

Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75(4):800–2.

Hsu J. Multiple comparisons: theory and methods: CRC Press; 1996.

Shaffer JP. Multiple hypothesis testing. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995;46(1):561–84.

Cao J, Zhang S. Multiple comparison procedures. JAMA. 2014;312(5):543–4.

Durso LE, Latner JD, Hayashi K. Perceived discrimination is associated with binge eating in a community sample of non-overweight, overweight, and obese adults. Obes Facts. 2012;5(6):869–80.

O’Brien KS, Latner JD, Puhl RM, Vartanian LR, Giles C, Griva K, et al. The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite. 2016;102:70–6.

Forbes Y, Donovan C. The role of internalised weight stigma and self-compassion in the psychological well-being of overweight and obese women. Aust Psychol. 2019;54(6):471–82.

Pötzsch A, Rudolph A, Schmidt R, Hilbert A. Two sides of weight bias in adolescent binge-eating disorder: adolescents’ perceptions and maternal attitudes. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(12):1339–45.

Puhl RM, Lessard LM, Himmelstein MS, Foster GD. The roles of experienced and internalized weight stigma in healthcare experiences: perspectives of adults engaged in weight management across six countries. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0251566.

Zuba A, Warschburger P. The role of weight teasing and weight bias internalization in psychological functioning: a prospective study among school-aged children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(10):1245–55.

Schvey NA, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. The stress of stigma: exploring the effect of weight stigma on cortisol reactivity. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(2):156–62.

Daly M, Sutin AR, Robinson E. Perceived weight discrimination mediates the prospective association between obesity and physiological dysregulation: evidence from a population-based cohort. Psychol Sci. 2019;30(7):1030–9.

Van Strien T, Herman CP, Anschutz DJ, Engels RC, de Weerth C. Moderation of distress-induced eating by emotional eating scores. Appetite. 2012;58(1):277–84.

Latner JD, Mond JM, Kelly MC, Haynes SN, Hay PJ. The loss of control over eating scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(6):647–59.

Wen Z, Fan X. Monotonicity of effect sizes: questioning kappa-squared as mediation effect size measure. Psychol Methods. 2015;20(2):193.

Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(2):93.

Durso LE, Latner JD. Understanding self-directed stigma: development of the weight bias internalization scale. Obesity. 2008;16(S2):S80–6.

Hilbert A, Baldofski S, Zenger M, Löwe B, Kersting A, Braehler E. Weight bias internalization scale: psychometric properties and population norms. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e86303.

Meadows A, Higgs S. A bifactor analysis of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale: what are we really measuring? Body Image. 2020;33:137–51.

Meadows A, Higgs S. The multifaceted nature of weight-related self-stigma: validation of the two-factor weight bias internalization scale (WBIS-2F). Front Psychol. 2019;10:808.

Austen E, Pearl RL, Griffiths S. Inconsistencies in the conceptualisation and operationalisation of internalized weight stigma: a potential way forward. Body Image. 2020.

Pearl RL, Hopkins CH, Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for internalized weight stigma: a pilot study. Eat Weight Disord-Stud Anorexia, Bulimia Obes. 2018;23(3):357–62.

Kaufmann LM, Bridgeman C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions that reduce weight stigma towards self or others. Innov Stigma Discrimination Reduction Programs Across World. 2021;141–88.

Marshall S, Mackay H, Matthews C, Maimone IR, Isenring E. Does intensive multidisciplinary intervention for adults who elect bariatric surgery improve post-operative weight loss, co-morbidities, and quality of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020;21(7):e13012.

Preiss K, Clarke D, O’Brien P, de la Piedad GX, Hindle A, Brennan L. Psychosocial predictors of change in depressive symptoms following gastric banding surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28(6):1578–86.

Pearl RL, Bach C, Wadden TA. Development of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for internalized weight stigma. J Contemp Psychother. 2022;1–8.

Pearl RL, Wadden TA, Bach C, Gruber K, Leonard S, Walsh OA, et al. Effects of a cognitive-behavioral intervention targeting weight stigma: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2020;88(5):470.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions HB is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship through ACU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB provided the existing dataset from a previous project. AH and HB cleaned and screened the raw data. HB wrote the code for the computation of raw data to total scores. HB and XPG conceptualised the study, planned and ran the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. LB, LK, and AH edited the manuscript, and all authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key points

• Research suggests internalised weight stigma mediates the relationship between perceived weight stigma and psychosocial correlates in several cohorts.

• However, few studies have assessed this effect in bariatric surgery samples, and in those that have, there is only mixed evidence of internalised weight stigma as a mediator of depression and anxiety.

• We found that, after controlling for BMI, internalised weight stigma mediated the relationship between perceived weight stigma and a range of psychosocial correlates, including symptoms of depression and anxiety, psychological quality of life, and some measures of disordered eating and body image—but not physical quality of life or pain.

• Although cross-sectional, the findings highlight the importance of internalised weight stigma for variables that are known to be related to adverse correlates in individuals seeking bariatric surgery.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bidstrup, H., Brennan, L., Hindle, A. et al. Internalised Weight Stigma Mediates Relationships Between Perceived Weight Stigma and Psychosocial Correlates in Individuals Seeking Bariatric Surgery: a Cross-sectional Study. OBES SURG 32, 3675–3686 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06245-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06245-z