Abstract

The aerospace and automotive industries are seeking advanced materials with low weight yet high strength and durability. Aluminum and magnesium-based metal matrix composites with ceramic micro- and nano-reinforcements promise the desirable properties. However, larger surface-area-to-volume ratio in micro- and especially nanoparticles gives rise to van der Waals and adhesion forces that cause the particles to agglomerate in clusters. Such clusters lead to adverse effects on final properties, no longer acting as dislocation anchors but instead becoming defects. Also, agglomeration causes the particle distribution to become uneven, leading to inconsistent properties. To break up clusters, ultrasonic processing may be used via an immersed sonotrode, or alternatively via electromagnetic vibration. This paper combines a fundamental study of acoustic cavitation in liquid aluminum with a study of the interaction forces causing particles to agglomerate, as well as mechanisms of cluster breakup. A non-linear acoustic cavitation model utilizing pressure waves produced by an immersed horn is presented, and then applied to cavitation in liquid aluminum. Physical quantities related to fluid flow and quantities specific to the cavitation solver are passed to a discrete element method particles model. The coupled system is then used for a detailed study of clusters’ breakup by cavitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Several studies suggest that the addition of nanoparticle reinforcements to light metals significantly enhances their mechanical properties. A clear increase in aluminum Young’s modulus (by up to 100 pct) and in hardness (by up to 50 pct) with the addition of carbon nanoparticles was reported in Reference 1. Another study indicated a slight enhancement in Brinell hardness of aluminum, magnesium, and copper-based MMNCs with Al2O3 and AlN nanoparticles.[2] The study suggested that a better dispersion of nanoparticles is needed. Other researchers also report agglomerations of nanoparticles made visible using high-definition scanning electron microscopy (SEM).[3] The potential of the technique to enhance material properties was nevertheless demonstrated in Reference 4. A dense uniform dispersion of dispersed silicon carbide nanoparticles (15 g, at 14 pct by volume) in magnesium was achieved through evaporation of the matrix alloy, leading to enhancement of strength, stiffness, plasticity, and high-temperature stability. However, on a practical size scale, agglomeration of particles remains a problem.

The agglomeration of particles in MMCs is related to the fact that micro- and especially nano-sized inclusions have a large ratio of surface area to volume. This causes surface forces such as van der Waals interaction and adhesive contact to dominate over the volume forces such as, e.g., inertia or elastic repulsion.

Various mechanisms of detachment of adhered particles have been reported in the literature,[5] including the effects of turbulent flow. It is expected that drag and shear forces in turbulent flow can improve separation of the particles and thus contribute to de-agglomeration. However, the drag force alone is not sufficient to overcome the adhesion forces. This can be qualitatively illustrated by comparing the Stokes equation for the drag force with the force required to break two spherical particles apart, known as the pull-off force, given by, e.g., Bradley[6]:

where v f and μ f are the velocity and dynamic viscosity of the melt and γ sl is the solid–liquid interfacial energy. For aluminum melt, the dynamic viscosity μ f = 0.0013 Pa s. Assuming the interfacial energy γ sl = 0.2 to 2.0 J/m2, Eq. [1] yields v f =100 to 1000 m/s. Such fluid velocity values can be locally achieved instantaneously as a result of the collapse of cavitation bubbles induced by the ultrasonic field.

Ultrasonic melt processing has been long known to improve significantly the quality and properties of light metallic alloys even without inclusions.[7,8,9] These improvements are primarily attributed to acoustic cavitation;[10] the term “cavitation” here is based on the definition of Neppiras[11] and is restricted to cases involving the formation, expansion, pulsation, and collapse of existing gas cavities and bubble nuclei. The sonication of metals near their liquidus temperature was shown to improve degassing of the liquid metal, as well as to enhance nucleation and ultimately to refine the microstructure of the metal.[7,9]

Ultrasonic melt processing is also considered a potential technology for breaking up existing particle clusters and enabling their dispersion. Indeed, applying electromagnetic induction stirring in combination with ultrasonic vibrations was found beneficial for nanoparticle dispersion in metal melts.[1,12]

To improve the understanding of how this process works from the modeling point of view, the cavitation process is first examined. In the following section, a high-order acoustic model is presented, coupled with a model of cavitation. This model was validated against acoustic pressures measured in water.[13] A high-order numerical method is used to discretize the wave equation in both space and time. The discretized equations are then coupled to the Rayleigh–Plesset equation using two different time scales to couple the bubble and flow scales, resulting in a stable, fast, and reasonably accurate method for the prediction of acoustic pressures in cavitating liquids. The model is then applied to the ultrasonic treatment of aluminum. The acoustic pressure, velocity as well as cavitation-specific physical quantities (such as bubble radius and bubble interface velocity and pressure) are then passed on to a discrete element method (DEM)-based particles solver that simulates the behavior of particle clusters close to a pulsating and collapsing bubble.

2 Theory

2.1 The Wave Equation

Sound propagation in a pure liquid is modeled by the continuity and momentum equations expressed in wave form:

where \( p \) is the acoustic pressure, \( v_{i} \) are the velocity components, \( \rho \) is the liquid density, and \( c \) is the speed of sound in the liquid. The source term \( S = \rho c^{2} \partial \phi /\partial t \) contains the bubbles’ contributions to acoustic pressure.

2.2 Bubble Dynamics

Bubbles are assumed to remain spherical as they oscillate radially in a pressure wave. The effect of bubble shape distortions on their resonant frequency is of the order of 2 pct,[14] and the surface tension between aluminum and hydrogen (the common gas phase in aluminum melts) is an order of magnitude larger than that of air and water. These two effects justify the assumption of sphericity for cavitating bubbles in ultrasonic melt processing. The Rayleigh–Plesset equation[15] can then be used to represent the bubble dynamics:

with

\( R \) is the bubble radius, \( p_{0} \) is the atmospheric pressure, \( p_{b} \) is the pressure inside the bubble, \( p_{v} \) is the liquid vapor pressure, \( p_{\infty } \) is the pressure from the ultrasonic source, \( \sigma \) is the surface tension between the liquid and the bubble gas, and \( \mu \) is the dynamic viscosity of the liquid. The bubble pressure \( p_{b} \) is given by

where \( p_{g,0} \) is the initial bubble pressure and \( \kappa \) is the polytropic exponent. The volume fraction of bubble gas is then calculated as \( \phi = \frac{4}{3}\pi n_{0} R^{3} \) where \( n_{0} \) is the number of bubbles per unit volume.

2.3 Acoustic Cavitation Modeling

Sound propagation and bubble dynamics are solved using the procedure described in Reference 16. Equations [2] and [3] are solved using a high-order staggered finite difference method.[17] Spatial derivatives are evaluated on a 6-point stencil, with mirroring of variables at solid boundaries. The pressure above the liquid-free surface is fixed to 0 Pa, to model a 180 deg phase shift upon reflection. A 4-point stencil is used to evaluate temporal derivatives.[17] The Rayleigh–Plesset Equation [4] is solved explicitly using the fourth-order Merson’s method, with multi-staging for solver stability.[18]

2.4 Particle Modeling

DEM considers particles in a Lagrangian framework. Particles are assumed spherical. The linear and angular momentum equations are derived for each particle based on the fluid–particle, particle–particle interaction forces and torques as well as body forces:

where index i corresponds to i-th particle; m and J are the particle’s mass and moment of inertia; x—position; φ—orientation; F—forces; T—torques; and upper indices b, f, and p correspond to body (e.g., gravity and magnetic forces), fluid interaction (drag, lift), and particle interaction forces (see Figure 1), respectively. The overbar denotes a vector and the summation sign includes forces from all particles j in contact with particle i. Since particles are assumed spherical, the angular momentum equation is used to evaluate angular velocity instead of orientation. A brief overview of how particle–particle forces F ij are derived is given in the next section. The forces F ij incorporate normal and tangential elastic forces, adhesion, and friction. Forces F ij also depend on the history of loading during the collision as well as transitions of the contact state between slip/partial slip and no slip regimes. References are provided for further details.

2.5 Particle–Particle Forces

Typically, the spring-dashpot model accounts for particle–particle interaction[19,20] during collisions, in which, e.g.,[21] friction and adhesion forces are also added. The adhesion can be defined as the van der Waals attraction forces acting on elastically deformed surfaces. It is considered to be the driving force behind the formation of particle clusters. The model[22,23] used in this study (Figure 1) is based on that of Reference 21.

It should be noted, that in many industrial applications, especially where aluminum alloys are concerned, particle clusters might be connected with an oxide film. The contribution of oxide film adhesion to the force needed to break up a cluster is a matter of further research and has not been addressed in this paper.

2.6 Adhesion Theories

Bradley[6] first described the van der Waals force acting between two rigid spheres in contact and calculated the pull-off force as P c = 4πγR, where γ is the interfacial energy of the contacting materialsFootnote 1 and R is the radius of the sphere. This theory, however, did not take into account the increased contact area and therefore higher total van der Waals attraction force between elastically deformed bodies. Combining Hertzian contact theory with van der Waals attraction resulted in the independent development of the two most prominent adhesion models: JKR (Johnson, Kendall, and Roberts)[24] and DMT (Derjaguin, Müller, Toporov).[25] These two models are based on different assumptions of adhesion mechanisms: DMT assumes that adhesion enhances the elastic deformation of the contacting bodies, which nonetheless remains subject to Hertzian theory of spherical elastic contact. JKR on the other hand combines the Hertzian theory with a problem of rigid flat-ended punch. Adhesion is assumed present only across the area of contact of the bodies. Equations corresponding to both JKR and DMT models are compared in Tables I and II.

Muller[26] concluded that the adhesive contact of larger, softer bodies with stronger surface interaction could be described by the JKR model, while the DMT model is applicable to the smaller, harder bodies with weaker surface interaction. A parameter μ was introduced to determine which model is more appropriate:

where z 0 is the equilibrium separation distance, typically 0.16 to 0.4 nm. According to Muller if μ < 1 then DMT is applicable whereas if μ > 1, it is JKR.

Further developments of adhesion theories yielded the generalized models that provide a smooth transition between JKR and DMT models that are considered as two opposite extreme cases.[27,28] These models however require additional computations and are therefore impractical for use in DEM simulations.

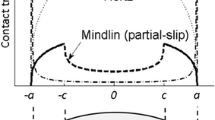

2.7 Oblique Contact

Hertz theory is used in most of the cases of normal impact of spherical bodies. In the case of oblique impact of bodies, tangential contact forces must be incorporated. Mindlin and Deresiewicz[29] developed the main theory connecting normal and tangential forces with normal and tangential displacements. It is assumed that two elastic spheres in tangential contact experience a partial slip, where the total force is a combination of elastic tangential force and sliding friction. Once the partial-slip tangential force exceeds the sliding friction force, the bodies slide relative to each other. The tangential force is then equivalent to the sliding friction force F s = ηP, where η is the friction coefficient and P is the normal load. The distribution of contact traction is illustrated in Figure 2. Thornton and Yin[21] combined all the major cases of the loading/unloading conditions described by Mindlin and Deresievicz.[29]

2.8 Oblique Contact with JKR Adhesion

Savkoor and Briggs[30] extended the JKR contact theory to consider the effect of adhesion in the case of oblique loading. It was suggested that applying the tangential force T reduces the potential energy by an amount of Tδ τ/2, where δ τ is tangential displacement. Adding this term to the JKR energy balance equation modified the contact radius (see Table II) as

It was concluded that in the presence of a tangential force, the contacting spheres peel off each other thus reducing the contact area. The peeling process continues until T reaches the critical value of

where G is the combined shear modulus of the contacting materials.

For normal load, Thornton and Yin[21] have adopted the JKT theory, while in the case of oblique loading they followed[31] in what concerns the peeling process. They however assumed that once the peeling process is complete, the contacting bodies operate in the partial slip regime as described before, with the difference that the normal force P is replaced with P+6πγR p . The Thornton and Yin model is used in the present study for the cases of JKR adhesion.

2.9 Oblique Contact with DMT Adhesion

It is suggested here to combine the Thornton and Yin[21] partial-slip no-adhesion model with DMT adhesion. The DMT theory assumes that the deformed shapes of the contacting bodies remain within Hertzian elastic theory. Therefore, a no-adhesion model was adopted where the normal force P is replaced with P+4πγR p to account for the adhesion force. The DMT modification of the Thornton and Yin model is used for the cases of DMT adhesion.

2.10 Particle–Fluid Forces

Other forces acting on particles come from particle–fluid interactions. These forces are listed in Table III. Discussion on other fluid–particle interaction forces and their models can be found in References 19, 32, and 33. R p denotes particle radius—not to be confused with average bubble radius R Reference 4.

2.11 Coupling of Acoustic Solver with the DEM Model

A one-way coupling between the acoustic solver and particles model was developed, with the effect of particles on the fluid flow and cavitation being neglected. This assumption is justified in the present model since the particle sizes are much smaller than the computational cell size and the flow and cavitation variables are averaged over each computational cell volume. To implement the particle–fluid interaction forces, fluid flow variables (pressure and velocity) and cavitation variables (average bubble radius R, bubble concentration θ, bubble interface pressure P b, and bubble interface velocity dR/dt) are passed to the particles model. These variables are averaged over their respective computational cells and within a time step of the acoustic solver. Due to this averaging process, the results can be accepted at present as qualitatively indicative of the locations in the melt where cluster breakup is possible, given the cavitation conditions.

3 Problem Description

3.1 Material Properties

Table IV lists the material properties used in the numerical experiments. The gas phase (hydrogen) is assumed adiabatic, i.e., \( \kappa = \gamma = 1.4 \). Table V lists the particle properties. Interfacial energy values are required for evaluating the adhesion force. This differs from the surface tension at the gas/fluid interface. The interfacial energy values of 0.2 and 2.0 J/m2 used in this study are hypothetical and do not correspond to a particular solid–liquid interface. Real values of interfacial energy depend on many factors, such as wetting, presence of gaseous phase, conductivity of the fluid, and particle material as well as particle material microstructure. More details about evaluating the interfacial energy can be found in References 21 and 30.

3.2 Ultrasonic Treatment Setup

Figure 3 represents a typical experimental setup for the ultrasonic treatment of aluminum[34] and corresponds to the simulation described in Reference 16. The crucible walls are reflective to sound waves, whilst a 180 deg phase shift occurs at the free surface. The liquid height is 17.5 cm and the diameter of the cylindrical base is 12 cm. This crucible volume corresponds to 5.2 kg of aluminum at 973 K (700 °C) . The operating frequency of the transducer is 17.7 kHz. The sonotrode tip is immersed 2 cm below the free surface.

Schematic of aluminum treatment setup.[34] The origin of the domain marked as a black dot is at the intersection of the axis and the plane 2 cm above the vibrating surface of the sonotrode

3.3 Particles Positioning

In this study, clusters were formed of 55 densely packed particles as shown in Figure 4.

Clusters were positioned in 6 rows of 1 cm gap and 9 columns of 0.5 cm gap as shown in Figure 5. The first row is 1 cm below the sonotrode. The y-position of the first row is −3 cm from the top of the crucible. The particle spatial configuration is 3-dimensional and de-agglomeration is modeled in 3D space. The acoustic solution represents a cross section of an axially symmetric process.

3.4 De-agglomeration

The de-agglomeration of particles involves breaking up large particle clusters into smaller ones or into individual particles. De-agglomeration was observed as a result of ultrasonic processing in aluminum.[35,36,37,38] During ultra-sonication of aluminum, hydrogen bubbles form, oscillate, and collapse, creating chaotic and intensive velocity pulses. The beneficial effect of ultrasound on de-agglomeration is attributed to these pulses. Little is known about the exact timing, location, and amplitude of these pulses. In Reference 37, the pulse velocity is estimated to be up to 3 km/s. The cavitation events are shown to be highly localized, i.e., the energy of the pulse dissipates quickly with both time and distance. In this study, the bubble surface velocity, dR/dt, obtained from the acoustic solver is used as a measure of the magnitude of such pulses. As the quantities related to the cavitation solver are averaged across computational cell and time step, they are attributed to the behavior of a representative bubble originating in the computational cell. It is assumed that velocity pulses propagate spherically originating from the initial cluster positions. The magnitude of the pulse is taken as dR/dt value within the 5R distance from the origin and then it decays with inverse squared distance, to maintain the fluid flow rate constant. The example of breaking a cluster of 55 particles by a spherical pulse is shown in Figure 6. A more detailed study of de-agglomeration of particles caused by spherical velocity pulses (but no coupling to the acoustic solver) was provided in Reference 22.

The de-agglomeration of a particle cluster is quantified as the average distance from particles that initially belonged to the cluster to their geometrical center, scaled by the particle radius:

where N p (=55) is the number of particles in a cluster, R p is a particle radius (constant in this study), x i denotes position, and bar is for the vector notation. Particles of 5 µm radius and interfacial energies of 0.2 and 2.0 J/m2 were subjected to the spherical velocity pulses caused by cavitation.

4 Results

4.1 Acoustic Cavitation

Figures 7(a) and (b) show the predicted instantaneous pressure field and schematic bubble distribution along a vertical mid-plane of the crucible at two different times. The pressure consists of a combination of the forcing sonotrode frequency and its harmonics and a random element caused by bubble oscillations or bubble collapses. The bubble cloud is denser below the sonotrode, as is expected. Due to acoustic shielding, the ultrasonic energy is attenuated by the cloud under the sonotrode, hence prohibiting the formation of further bubble structures away from the sonotrode. This is also consistent with experimental evidence of large pressure decay away from the radiating source.[37] However, bubbles survive at antinodes along the sonotrode axis (represented by gray spheres).

4.2 De-agglomeration of Particles

Figure 8(a) illustrates the magnitude of the pulse dR/dt at the initial position of 23rd cluster (x = 2 cm, y = −5 cm). A series of dR/dt values are marked on Figure 8 as ‘peaks’ p 1 ,..,p 7 preceded by ‘valleys’ v 1 ,..v 2 . Values corresponding to these peaks and valleys are listed in Table VI. The non-dimensional dispersion coefficient values D agg corresponding to a cluster of particles with interfacial energies γ = 0.2 and 2.0 J/m2, respectively, are shown in Figure 8(b). Figure 9 is a table containing images of particles and cluster condition at peaks p 1 –p 7. Colors (online version) in Figures 9, 10, and Appendix A are used to distinguish sub-clusters formed after breakup. Note that the peaks p 1 and p 2 are unable to cause visible damage to the cluster with either interfacial energy. Peak p 3 despite having a lower value (1.42 m/s) than peak p 1 (2.2 m/s) is able to break the lower energy cluster.

(a) The value of bubble surface velocity, dR/dt plotted at the initial position of the 23rd cluster (x = 2 cm, y = −5 cm), for a time interval 0.12 to 0.25 ms of processing, (b) the corresponding non-dimensional dispersion parameter D agg as defined by Ref. [12] for two different particle surface energy levels

This is also confirmed by the D agg plot in Figure 8(b). The valley-peak difference is however higher for p 3–v 3 than for p 1–v 1 which allows us to conclude that the peak-valley fluctuation magnitude of dR/dt is a factor responsible for de-agglomeration. The cluster with higher interfacial energy (Figure 9 lower row) does not break until p 8 where the peak–valley difference is 18 m/s. A significant rise in D agg for the higher energy cluster can be observed between p 7 and v 8, which corresponds to a bubble implosion rather than growth. Increase of the D agg value can be explained by movement of the cluster away from the origin of the pulse, so that the more remote part of the cluster is subjected to the implosion by a lesser degree than the other part. When the implosion originates inside a cluster where particles are in tight contact, the elastic rebound of the particles can cause the cluster to de-agglomerate. On the other hand, in the absence of particle contact, the implosion may cause a decrease in D agg as seen in Figure 8(b) on the lower energy cluster curve between p7 and v8. The direct influence of the velocity fluctuations on the cluster is shown in Figure 10, correlating bubble successive collapses with sharp velocity spikes and breakup.

Appendix A shows the behavior of the full cluster matrix at two different time steps for low and high surface energy.

5 Conclusions

The coupling of an acoustic solver with a DEM model for particles was implemented, providing an efficient numerical tool for studying the mechanisms of particle cluster breakup due to cavitation. The fluctuations of interfacial bubble velocities obtained from the acoustic solver were correlated to the breakup of clusters, as illustrated in Table VI and quantified by a non-dimensional parameter D agg defined in Eq. [12] as shown in Figure 8(b). Both higher and lower interfacial energy clusters eventually broke up which suggests that even averaged values of dR/dt are sufficiently large for the breakup to occur. Further analysis of the behavior of clusters placed in a 54-position matrix below the sonotrode allows the determination of the regimes of sonication that are most favorable to the de-agglomeration of particles. Important parameters related to the intensity of sonication include the distance from the sonotrode and the location of resonant nodes/antinodes in the sound field, identified by the appearance of cavitation bubbles in specific locations as shown in Figure 7.

Notes

The formulae for the pull-off force of adhered particles are often used with the notation Δγ, which is the work of adhesion. For spheres of the same material Δγ ≈ γ/2, therefore P c = 2π ΔγR p .

Abbreviations

- \( c \) :

-

Speed of sound in melt

- \( C_{d} \) :

-

Drag coefficient

- \( F \) :

-

Force on particle

- \( J_{i} \) :

-

Moment of inertia of particle \( i \)

- \( K \) :

-

Bulk modulus of liquid

- \( m_{i} \) :

-

Mass of particle \( i \)

- \( n_{0} \) :

-

Number of bubbles per unit volume

- \( P \) :

-

Normal load

- P c :

-

Pull-off force between two rigid spheres in contact

- p :

-

Pressure

- p 0 :

-

Atmospheric pressure

- p b :

-

Pressure inside bubble

- p v :

-

Vapor pressure

- p g,0 :

-

Initial bubble pressure

- \( p_{\infty } \) :

-

Ultrasonic source pressure

- \( R \) :

-

Bubble radius

- \( R_{0} \) :

-

Equilibrium bubble radius

- \( R_{p} \) :

-

Particle radius

- T :

-

Torque on particle

- v f :

-

Melt velocity

- x :

-

Position

- z 0 :

-

Equilibrium separation distance between particles

- δ τ :

-

Tangential displacement

- η :

-

Friction coefficient

- φ :

-

Particle orientation

- ϕ:

-

Bubble volume fraction

- κ :

-

Polytropic exponent

- Ω :

-

Vorticity

- ω:

-

Angular velocity of particle

- γ sl :

-

Solid–liquid interfacial energy

- μ f :

-

Dynamic viscosity of melt

- ρ :

-

Melt density

- σ :

-

Surface tension

- Re:

-

Reynolds number

References

S. Vorozhtsov, D. Eskin, A. Vorozhtsov, S. Kulkov: in Light Metals, J. Grandfield, ed., TMS (The Minerals, Metals and Materials Society), 2014, pp. 1373–77.

J. Tamayo-Ariztondo, S. Vadakke Madam, E. Djan, D.G. Eskin, N. Hari Babu, Z. Fan: in Light Metals, J. Grandfield ed., TMS, 2014, pp. 1411–15.

Y. Yang, J. Lan and X. Li, J. Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 380 (2004), pp 378–383

Lian-Yi Chen, Jia-Quan Xu, Hongseok Choi, Marta Pozuelo, Xiaolong Ma, Sanjit Bhowmick, Jenn-Ming Yang2, Suveen Mathaudhu & Xiao-Chun Li, Nature (2015), 528 (7583), pp 539–543

M. Soltani and G. Ahmadi, J. Adhes. Sci. Technol., (1994), 8(7), pp 763–85

R.S. Bradley: London, Edinburgh Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1932, vol. 13, pp. 853–62

G.I. Eskin, D.G. Eskin, Ultrasonic Treatment of Light Alloy Melts, Second ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014

J. Campbell, Int. Mater. Rev., (1981), 26 pp 71–108

O.V. Abramov, Ultrasonics, (1987), 25, pp 73–82

G.I. Eskin, Ultrason. Sonochem., (1995), 2 pp 137–141

E. Neppiras, Ultrasonics, (1984) 22 pp 25–28.

Y Xuan, L Nastac, High Temp. Mater. Processes (2017), 36 (4), pp 381–387

C. Campos-Pozuelo, C. Granger, C. Vanhille, A. Moussatov, B. Dubus, Ultrason. Sonochem., (2005), 12, pp 79–84

Strasberg, M., J. Acoust. Soc. Am., (1953), 25 (3), p 536

Plesset, M. S. J. Appl. Mech., (1949), 16, pp 277–282,

Lebon, G. S. B., Tzanakis, I., Djambazov, G., Pericleous, K. and Eskin, D. G., Ultrason. Sonochem., (2017), 37, pp 660–668,

Djambazov, G. S., Lai, C. H. and Pericleous, K. A., AIAA J., (2000), 38 (1), pp 16–21,

Y. Laevsky: Intel® Ordinary Differential Equation Solver Library, Intel Corporation, (2008)

Zhu, H.P., Zhou, Z.Y., Yang, R.Y., Yu, A.B., Chem. Eng. Sci. (2007), 62, pp. 3378–3396

C. Goniva, C. Kloss, A. Hager, G. Wierink, S. Pirker: Proc. 8th Int. Conf. CFD in Oil & Gas, Metall. and Process Ind. 2011, paper 141, pp. 1–9

Thornton, C., Yin, K. K. Impact of elastic spheres with and without adhesion. Powder Technol. (1991), 65, pp. 153–166

Manoylov, A., Bojarevics, V. and Pericleous, K. (2015), Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 46A (7) pp. 2893–2907

A. Manoylov, G. Djambazov, V. Bojarevics, and K. Pericleous: Proc. ECCOMAS Congress VII European Congress on Computational Methods, M. Papadrakakis, V. Papadopoulos, G. Stefanou, V. Plevris eds., 2016, pp. 8207–24

K. L. Johnson, K. Kendall and A.D. Roberts, Proc. R. Soc. A (1971), 324, pp. 301–313

B. V. Derjaguin, V.M. Muller and Y.P. Toporov, J. Coll. Int. Sci., (1975), 53(2), pp. 131–143

V. M. Muller, V. S. Yushenko and B.V. Derjaguin, J. Coll. Int. Sci. (1980) 77(1) pp. 91-101

D. Maugis J. Coll. Int. Sci. (1992) 150(1), pp. 243–269

J. A. Greenwood, K. L. Johnson, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 31(1998), 3279–3290

R.D. Mindlin and H. Deresiewicz: J. Appl. Mech., Trans. ASME, (1953). 20, pp. 327–44

A. R. Savkoor and G. A. D. Briggs, Proc. Roy. Soc. A (1977), 356, pp. 103–114

J. N. Israelachvili, Intermolecular and Surface Forces, Academic Press, New York, (1985)

J. S. Marshall, J. Comp. Physics (2009) 228, pp. 1541–1561

J. S. Marshall, and S. Li, Adhesive Particle Flow: A Discrete-Element Approach, Cambridge University Press, New York, (2014)

I. Tzanakis, G. S. B. Lebon, D. G. Eskin and K. A. Pericleous, J. Mater. Process. Technol. (2016) 229, pp. 582–586

O.B. Kudryashova, S.A. Vorozhtsov, A. Khrustalyov and M. Stepkina: AIP Conf. Proc., 2016, vol. 1772, 1, pp. 020013-1–020013-6

G. I. Eskin, G. S. Makarov and Y. P. Pimenov, Adv. Perf. Mater., (1995) 2 (1), pp. 43–50

Y. Yang, J. Lan and X. Li, Mater. Sci. Eng., A, (2004) 380, pp. 378–383,

X. Li. Y. Yang, D. Weiss, AFS Transactions, American Foundry Society, Schaumburg, IL, USA (2007), Paper 07-133(02)

J. G. Speight, Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry, McGraw-Hill, New York (2005)

I. Waller, and I. Ebbsjo, J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys., (1979)12 (18), L705

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from two research projects in this work: FP7 ExoMet (co-funded by the European Commission (contract FP7-NMP3-LA-2012-280421), by the European Space Agency and partner organizations) and the project UltraMelt (contract EP/K00588X/1) funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Manuscript submitted May 5, 2017.

Appendices

Appendix A

See Figures A1, A2, A3 and A4.

History of 54 clusters at two successive time intervals for two different surface energy levels.

Appendix B: Summary of Modeling Approach

Conservation of mass

Conservation of momentum

Bubble dynamics

Particle dynamics

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Manoylov, A., Lebon, B., Djambazov, G. et al. Coupling of Acoustic Cavitation with Dem-Based Particle Solvers for Modeling De-agglomeration of Particle Clusters in Liquid Metals. Metall Mater Trans A 48, 5616–5627 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-017-4321-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-017-4321-5