Abstract

Summary

The annual number of patients treated for osteoporosis between 1998 and 2018 in Switzerland increased until 2008 and steadily decreased thereafter. With a continuously growing population at fracture risk exceeding an intervention threshold, the treatment gap has increased and the incidence of hip fractures has stopped declining in the past decade.

Introduction

The existence of an osteoporosis treatment gap, defined as the percentage of patients at risk for osteoporotic fractures exceeding an intervention threshold but remaining untreated, is widely acknowledged. Between 1998 and 2018, new bone active substances (BAS) indicated for the treatment of osteoporosis became available. Whether and if so to what extent these new introductions have altered the treatment gap is unknown.

Methods

The annual number of patients treated with a BAS was calculated starting from single-drug unit sales. The number of patients theoretically eligible for treatment with a BAS was estimated based on four scenarios corresponding to different intervention thresholds (one based solely on a bone mineral density T score threshold and three FRAX-based thresholds) and the resulting annual treatment gaps were calculated.

Results

In Switzerland, the estimated number of patients on treatment with a BAS increased from 35,901 in year 1998 to 233,381 in year 2018. However, this number grew regularly since 1998, peaked in 2008, and steadily decreased thereafter, in timely coincidence with the launch of intravenous bisphosphonates and the RANKL inhibitor denosumab. When expressed in numbers of untreated persons at risk for osteoporotic fractures exceeding a given intervention threshold, the treatment gaps were of similar magnitude in 1998 (when the first BSAs just had become available) and 2018. There was a strong association, which does not imply causation, between the proportion of patients treated and hip fracture incidence.

Conclusion

In Switzerland, the osteoporosis treatment gap has increased over the past decade. The availability of new BAS has not contributed to its decrease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a crippling disease with alterations in bone quantity and quality leading to an increased risk of fragility fractures most commonly located at the hip, spine, distal radius, and/or proximal humerus, also known as major osteoporotic fractures (MOF). The operational definition of osteoporosis proposed by the World Health Organization relies on a T score at or below 2.5 measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) at the femoral neck [1].

In Switzerland, approximately 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men will sustain a fragility fracture during their remaining lifetime after age 50 [2]. While increasing in number, the incidence and even more so the age-standardized incidence of hospitalizations for hip fractures have been shown to follow a long-lasting decreasing trend between 1998 and 2018 in both men and women [3]. During these 21 years of observation, the proportion of hospitalizations for hip fractures of all hospitalizations for MOF decreased from approximately 55% in both men and women to 44% and 42% in men and women, respectively. Among the most prescribed osteoporosis drugs in Switzerland, the aminobisphosphonates alendronate and zoledronate and the RANKL inhibitor denosumab were shown to significantly reduce the risk of hip fractures in fracture endpoint trials [4,5,6] and their use may have contributed to the observed reduction in hip fracture incidence.

Since the launch of the first oral bisphosphonate approved for the treatment of osteoporosis in Switzerland (alendronate in 1996), an array of drug therapies aiming at reducing fracture risk in patients with osteoporosis has been made readily available to physicians and patients, allowing for multiple therapeutic options based on different mechanisms of action, efficacy and safety profiles, and administration routes and schemes. In Switzerland, approved and reimbursed osteoporosis pharmacological treatments include bisphosphonates (as daily, weekly, or monthly tablets and as quarterly or yearly intravenous infusions), denosumab as twice yearly subcutaneous injections, teriparatide as daily subcutaneous injections, and raloxifene as daily tablets. Of note, reimbursement restrictions generally based on a DXA T score threshold and/or the presence of one or more prevalent fractures, apply to all except alendronate (Supplemental table S1). Off-label prescriptions and prescriptions of non-reimbursed drugs are the exception rather than the rule and can be considered negligible.

In earlier publications, different groups have used different methodologies and definitions for estimating the osteoporosis treatment gap. While the common understanding is that treatment gap defines the proportion of patients who do not get treatment although eligible for therapy based on a given intervention threshold, the source databases and the inclusion criteria differed widely. Some authors estimated the treatment gap based either on national health databases and database linkage such as the National Danish Health Registries [7] or the National Medicare Database in the US [8] and others performed prospective studies such as the Austrian ICUROS [9] and the Belgian FRISBEE [10] studies. Typically, all these studies included patients who had experienced an index major osteoporotic fracture, either only women [8, 10] or both men and women [7, 9] with diverging criteria regarding age at inclusion. The gap was then estimated on these (sub-)populations with treatment generally defined as one of the bone active substances described above and generally excluding calcium, vitamin D, and estrogens, at the exception of the study by Malle et al. in which the latter were included [9]. By contrast, the SCOPE 2021 project, aiming at standardizing the approach for cross-country comparisons (EU27 + Switzerland + United Kingdom), followed a different methodology. SCOPE 2021 defined the patient population eligible for treatment as those with a 10-year probability of MOF exceeding that of a woman with a prior fragility fracture, estimated the number of patients treated based the IQVIA drug sales database (whereby calcium, vitamin D, and estrogens were not considered), and adjusted for adherence by using a point estimate derived from the Swedish Prescribed Drugs Register [11]. Thus, treatment gap studies and results should not be compared directly without the necessary caution with regard to the methodology applied.

The aim of the present analyses was to determine the number of patients treated with a pharmacologically active osteoporosis drug in Switzerland between 1998 and 2018, to evaluate the changes in treatment patterns following the introduction of new substances, to identify and quantify a potential osteoporosis treatment gap, and to explore the association between treated patients and changes in hip fracture incidence.

Methods

Yearly sales of counting units (i.e., the smallest available single dosage of a preparation, e.g., a tablet or a vial) of all pharmacologically active osteoporosis drugs including generics in all formulations, dosage strengths, and presentations available in Switzerland since 1998 and up to year 2018, were obtained from IQVIA Switzerland (IQVIA RDS Switzerland Sàrl, Saint-Prex, Switzerland). Pharmacologically active osteoporosis drugs were defined as oral bisphosphonates (alendronate 10 mg daily or 70 mg weekly, risedronate 5 mg daily or 35 mg weekly, ibandronate 150 mg QM, including generics), intravenous bisphosphonates (ibandronate 3 mg Q3M and zoledronate 5 mg Q12M), denosumab 60 mg Q6M, raloxifene 60 mg daily, and teriparatide 20 mcg daily. Not included were abaloparatide and strontium ranelate (not available in Switzerland) and basedoxifene (available but not reimbursed). Early bisphosphonates (including etidronate, clodronate, and pamidronate) were neither available in Switzerland nor approved for the treatment of osteoporosis and thus not included in the analysis. Counting units were converted into treatment-years by applying the annualized recommended dose for the treatment of osteoporosis published in the Swiss prescribing information (https://compendium.ch). Of note, prescription data were not available by sex, such that only the total number of patients treated could be calculated.

In the absence of Swiss data, persistence defined as the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy was calculated based on previously published findings in women with US Medicare fee-for-service coverage [12]. The annual persistence rates of women with records covering three years or more were averaged leading to values of 0.596, 0.476, and 0.312 for denosumab, intravenous bisphosphonates, and oral bisphosphonates, respectively. The number of patients on treatment with a pharmacologically active osteoporosis drug in a given year was obtained by multiplying the number of treatment-days for each substance with the corresponding persistence values. It was assumed that persistence did not change between 1998 and 2018.

The total number of patients eligible for treatment (patient potential) was estimated based on four scenarios. For all, the annual Swiss population statistics by sex and 5-year age groups after age 45 published by the Swiss Federal Office of Statistics were used as a starting point. The most conservative scenario considered that the patient potential was restricted to men and women with a T score at or below − 2.5 at the femoral neck or the lumbar spine. The latter was estimated based on the published US osteoporosis prevalence rates of 3.9% and 15.8% in non-Hispanic White men and women [13]. In this study, reference groups used for the femoral neck and the lumbar spine were 20–29 year-old non-Hispanic White females from NHANES III and 30-year old White females from the DXA manufacturer database, respectively [13]. The three other scenarios for estimating the patient potential were defined based on FRAX risk thresholds by 5-year age groups for MOF in men and women. The FRAX algorithm allows for the country-specific calculation of the individual 10-year absolute risk of either hip fracture or MOF based on clinical risk factors with or without BMD. For the purpose of this analysis, the number of men and women aged 45 years or older with a FRAX risk for MOF exceeding 15% or 20% or exceeding the risk of a Swiss woman with a prior fracture was calculated based on previously published prevalence data used for the Swiss-specific FRAX model (https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/) calibrated for Swiss-specific fracture risk and life expectancy [2, 14, 15]. It was assumed that fracture risk in the age group 45–49 years was identical with that in the age group 50–54 years. The thresholds of 15% and 20% were chosen because osteoporosis treatment had previously been shown to be cost-effective in the Swiss healthcare setting with a 10-year probability for a MOF at or above 15.1% (range 9.9 to 19.9%) and 13.8% (range 10.8 to 15.0%) in men and women, respectively [14]. The prior fracture risk equivalent threshold, i.e., the 10-year fracture probability for MOF exceeding that of a woman with a prior fragility fracture according to the FRAX algorithm calibrated for Switzerland, was chosen because of its general acceptance in the Swiss health economic context (almost all drugs are reimbursed in the presence of a positive fracture history) and in the latest recommendations for osteoporosis treatment from the Swiss Association Against Osteoporosis (SVGO/ASCO) [16]. Furthermore, earlier findings suggested that osteoporosis treatment was cost-effective or cost-saving in the Swiss setting after the age of 55 years in men and 60 in women who had previously sustained a fragility fracture [14, 15]. For each FRAX-based scenario, the age-specific proportion of men and women qualifying for the predefined fracture risk categories was applied to the annual structure of the Swiss population from year 1998 through year 2018.

The annual osteoporosis treatment gap was defined as the absolute or relative difference between the patient potential and the number of treated patients between 1998 and 2018.

The number of hospitalizations for hip fractures in men and women aged 45 years and older were extracted for the years 1998 through 2018 from the Swiss Federal Office of Statistics health database using the ICD-10 codes S72.0 Fracture of the femoral neck, S72.1 Pertrochanteric fracture, and S72.2 Subtrochanteric fracture) [3]. The crude incidence of hip fractures in men and women pooled was calculated per 100,000 person-years. In the absence of available covariates, the degree of association between the number of patients treated by year and the earlier reported decrease in hip fracture incidence [3] was explored by univariate regression analyses. It was considered that all hip fractures were hospitalized.

Results

Treatment-years with pharmacologically active osteoporosis drugs between 1998 and 2018

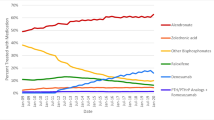

Figure 1 shows the treatment-years (assuming full persistence and compliance) by pharmacologically active osteoporosis drug and year since 1998. The cumulated total number of patient-years of therapy in the IQVIA database was 1.894 Mio during 21 years of observation of which 914,979 with oral bisphosphonates (48.3%), 547,600 with IV bisphosphonates (28.9%), 359,814 with denosumab (19.0%), 56,333 with raloxifene (3.0%), and 15,430 with teriparatide (0.8%). Thus, raloxifene and teriparatide were excluded from further processing.

Patients treated

After adjustment for persistence and as shown in Table 1, the estimated number of patients on treatment with a pharmacologically active osteoporosis drug increased from 35,901 in year 1998, i.e., two years after the launch of alendronate, to 233,381 in year 2018. While in year 1998, all patients were treated with alendronate as the only available option, in year 2018, 35.7% were treated with denosumab, 34.3% with an intravenous bisphosphonate (ibandronate 20.3%), and 30.0% with an oral bisphosphonate (alendronate 19.8%). The number of patients treated grew regularly since 1998, peaked in 2008, flattened in 2009, and steadily decreased since then. Of note, the IV bisphosphonates were launched in Switzerland in 2006 (ibandronate) and 2007 (zoledronate) and denosumab in 2010.

Patient potential based on different scenarios

The DXA T score ≤ − 2.5 scenario based on NHANES data used the US prevalence rates of 3.9% and 15.8% in non-Hispanic White men and women, respectively. For all scenarios based on FRAX Switzerland, the proportion of patients applied to the annual population structure is shown by 5-year age groups and sex in Table 2. The aggregated numbers of patients eligible for osteoporosis treatment between 1998 and 2018 are shown by scenario in Fig. 2. In all scenarios, the patient potential increased by 36.0 to 39.5% during the 21-year observation period, mainly reflecting the fast aging of the Swiss population. When considering patients with a DXA T score at or below − 2.5 at either the hip or the lumbar spine, the absolute number of patients (men and women) eligible for treatment based on the DXA-based operational definition of osteoporosis increased from 291,258 to 401,751 (+ 110,493) between 1998 and 2018. At the other extreme, the number of patients with a FRAX-based risk for MOF exceeding 15%, at which it still was cost-effective to treat osteoporosis in Switzerland, increased from 641,687 to 895,310 (+ 253,623).

Treatment gap

The osteoporosis treatment gap, defined as the difference between the potential of patients eligible for osteoporosis treatment and the number of patients treated, varied based on the intervention thresholds retained for the different scenarios (Table 3). The common pattern was a steadily decreasing treatment gap between 1998 and 2008 followed by a one-year plateau and a continuous increase up to 2018. As an example, Fig. 3 depicts the number of patients treated with an oral bisphosphonate, an intravenous bisphosphonate, or denosumab between 1998 and 2018 and the corresponding treatment gap for patients with a 10-year fracture probability for MOF exceeding that of a woman with a prior fragility fracture according to the FRAX algorithm calibrated for Switzerland. While the number of treated patients stopped increasing and even decreased after the introduction of the intravenous bisphosphonates and denosumab, the number of patients eligible for treatment continued to increase steadily, resulting in a growing treatment gap since 2008. In this scenario, 449,328 men and women were at risk in 1998 of which 35,901 were treated leaving 413,427 patients untreated (treatment gap 92.0%). In 2018, 610,822 were at risk of which 233,381 treated and 377,501 untreated (treatment gap 61.8%). Thus, in terms of absolute numbers, the treatment gap in 2018 can be considered as only marginally different from that observed in 1998, i.e., in the very early days of availability of osteoporosis drugs proven to reduce fracture risk.

Association with changes in hip fracture incidence

In Switzerland, the number of hospitalizations for hip fractures has continuously increased since 1998 in both men and women, mainly due to the rapid aging of the population [3]. The age-standardized and, to a lesser extent, the crude incidence of hospitalizations for hip fractures have been regularly decreasing since 1998 in both men and women [3]. The crude pooled incidence of hip fractures in men and women aged 45 years or older was 354 per 100,000 persons in 1998, 300 in 2008 (Fig. 4a), 297 in 2009, and 297 in 2018 (Fig. 4b.). The corresponding proportions of patients treated for osteoporosis were 12.7, 81.9, 90.0, and 60.0 per 1000 men and women aged 45 years or older.

Between 1998 and 2018, the annual crude incidences of hip fractures in men and women aged 45 years or older (per 100,000, pooled) was not significantly associated with the proportion of these under treatment with a pharmacologically active osteoporosis drug (per 1000). However, when considering specific time intervals, this association was significant between 1998 and 2008 (r = − 0.89 (95%CI − 0.97 to − 0.63), r2 = 0.80, two-sided p < 0.001) but not between 2009 and 2018 (r = 0.54 (95%CI − 0.14 to 0.87), r2 = 0.29, two-sided p = 0.108). Thus, the incidence of hospitalizations for hip fractures stopped decreasing together with the stagnation of and decrease in the proportion of patients treated for osteoporosis.

Discussion

The present analysis represents a pragmatic and easily reproducible approach to the evaluation of the treatment gap. Key findings include the observation that the introduction of intravenous bisphosphonates (ibandronate and zoledronate) and of the RANKL inhibitor denosumab has not resulted in a further increase of the total number of patients treated. Of mirrored concern, the treatment gap, which had been constantly decreasing since 1998, reached its nadir in 2008 and steadily increased thereafter. Keeping in mind that the secular decrease in hip fracture incidence had already started in 1998 to 2001, i.e., at a time where the number of treated patients was low, there was a strong association, which does not imply causation, between the decrease in hip fracture incidence and the number of patients treated with a pharmacologically active osteoporosis drug.

Using a more comprehensive and therefore complex modeling approach aimed at estimating the clinical and economic burden of osteoporotic fractures in year 2010, the osteoporosis treatment gaps in men and women in Switzerland were estimated at 36 and 58%, respectively [17]. In the present analysis, the calculated treatment gap for both sexes taken together varied from 27 to 66% in year 2010 depending on the fracture risk threshold for intervention scenario considered as acceptable. Importantly, while all of these scenarios were shown to be cost-effective or even cost-sparing in the Swiss setting [14], none exactly reflects the current requirements for reimbursement of osteoporosis drugs in Switzerland. The latter stipulate cum grano salis that reimbursement is warranted in the presence of a T score at or below − 2.5 and/or a prevalent (fragility) fracture only. From a clinical perspective, treating patients having experienced one or more fragility fractures and thus all individuals with a 10-year fracture probability exceeding that of a woman with a prior fragility fracture may be more acceptable to physicians than a cost-effective intervention threshold expressed as percent risk [11, 16, 17]. However, such an approach may lead to treating a minority of patients at highest risk, while a majority of patients at lower but still increased risk may not be granted reimbursed access to treatment. In terms of total number of fractures, the end result would be that a large number of fractures would still occur in unprotected patients at risk and undermine achievable better public health results at the global population level. This triggers and further supports recent developments suggesting that a population-based screening for fracture risk in postmenopausal women based on FRAX should be considered, in addition to the currently implemented high-risk case finding and treatment approach, for incorporation in many healthcare systems to reduce the burden of fractures [18, 19].

The calculation of the number of patients on therapy should be considered with the caution relative to the underlying assumptions. The drug-specific adjustments for persistence were taken from a subset of Medicare patients with fee for service coverage who had stayed on therapy for at least three years [12]. Whether similar persistence rates apply to Switzerland is likely but not established. Whether these rates vary over time is also unknown. However, considering that persistence is generally better in patients treated with denosumab than with IV bisphosphonates and worst with oral bisphosphonates has been repeatedly shown in the literature [20,21,22,23]. More important than the absolute values, the changes over time allow for internal consistency and acceptable comparability. It is remarkable that the introduction of intravenous bisphosphonates and denosumab has not contributed to a market expansion in terms of number of patients treated, although the pool of eligible patients has increased over time due to the rapid aging of the population. A possible explanation is that at the time of launch of the early bisphosphonates all efforts were concentrated towards case finding, i.e., identifying new patients eligible for treatment aimed at reducing fracture risk within the boundaries set by reimbursement restrictions. Ten years later, when ibandronate (oral in 2005, intravenous in 2006), zoledronate (2007), and denosumab (2010) were launched, an established market of almost 250,000 patients, already identified and treated with an oral bisphosphonate, existed. In such a situation, recommended marketing strategies aim at “picking the low hanging fruits” for fast market penetration, i.e., at switching patients on therapy to the new substance. Another explanation could be that the market was already saturated, i.e., that all eligible and accessible patients had already been treated which seems unlikely in the context of a growing patient potential. Finally, the number of newly identified patients starting on an osteoporosis drug and of those already diagnosed who resume treatment after an interruption may be equal to the number of patients stopping treatment. The concept of drug holiday in low-risk patients treated during 3 to 5 years with a bisphosphonate was introduced in 2011 based on a FDA recommendation [24] triggered by considerations related to bisphosphonate accumulation in bone [25], potentially sufficient residual effects on fracture risk after treatment discontinuation in low risk patients [26,27,28], and safety concerns regarding rare reported of uncommon adverse events (osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures) [29]. While holiday implies that treatment will be reinitiated and recommendations insisted on the importance of regular reassessments, many patients may have been lost to follow-up.

It was also intriguing to observe that the SERM raloxifene (reimbursed in Switzerland if the T score is at or below − 1) and the bone anabolic substance teriparatide (reimbursed as a second-line therapy after a new fracture occurring under treatment with a bisphosphonate or denosumab) were virtually inexistent in terms of patients treated, both representing less than 2% of the treatment-days in year 2018. According to T score-based US prevalence data, 15.8% of all White non-Hispanic women should have a T score at or below − 2.5 and 52.6% a T score at or below − 1 which corresponds to more than a tripling of the patient potential. Obviously, osteoporosis treatment is reserved to those at highest risk and little to no pharmacological intervention is the rule in patients with osteopenia. By contrast and consistent with the available published evidence, many patients with highest fracture risk (e.g., patients with multiple vertebral fractures) should have been eligible for treatment with the only bone anabolic substance available during the period of observation under scrutiny, namely, teriparatide [30]. Here again, available data suggest important underuse. Overall, these findings plead in favor of an urgent need for drug prescription data with higher granularity which would allow evaluating the treatment gap by risk categories and by sex.

Overall, the present findings suggest that the key challenges for overcoming the treatment gap published in a 2017 narrative global perspective on strategies for the prevention of fragility fractures need more urgent attention than ever [31]. Case finding and management of individuals at high risk of fracture should be revitalized, raising public awareness about osteoporosis and fragility fractures should be amplified or reinitiated, improving reimbursement and health system policies should ensure access to the most appropriate treatments to those patients expected to benefit most, and optimizing our epidemiological understanding of osteoporosis and fractures should include tools for regular progress assessment. For that, the newly proposed scorecard within the SCOPE project should be considered as an excellent starting point to be tailored to individual countries’ specific needs [11].

Among the strengths of this study is the straightforward and reproducible approach to the treatment gap calculation ensuring internal data consistency and allowing for monitoring changes over time. It also overcomes the challenges met when trying to estimate treated patient numbers based on DDDs (defined daily dosages). The latter are mandated by the WHO in order to ensure worldwide data comparability but sometimes suffer from important deviations when put into perspective with the approved dosing schemes. Limitations include that the IQVIA drug sales database does not report drug use by indication. While some of the drugs used for the treatment of osteoporosis have additional indications (such as the prevention of bone loss under antihormonal treatments or Paget’s disease of bone), the impact on the number treated patients can be considered as limited. The latter is further warranted by the existence of specific formulations for additional indications unrelated to osteoporosis, such as zoledronate 4 mg or denosumab 120 mg monthly, both for oncological indications, which were excluded from the present analysis. The IQVIA database does not report drug use by sex, such that an overall approach pooling men and women was chosen at the expense of a loss in data granularity. The IQVIA database does not either collect clinical characteristics which also preempted a more detailed analysis by gradients of fracture risk. Assumptions regarding persistence and DXA-based osteoporosis prevalence where taken from US publications which may differ from the Swiss reality, highlighting the urgent need for further epidemiological research at the individual country level. In the absence of better data, it was assumed that persistence, which addresses the question of how long a patient stays on therapy after treatment initiation, did not change between 1998 and 2018. Whether and to what extent prescription behavior and persistence have been impacted by real or suspected emerging safety concerns with antiresorptives, including the scientific discussions around atypical femoral fractures, osteonecrosis of the jaw, and atrial fibrillation events, remains unknown and deserves further research. On the other hand and complementary to that, adherence to the prescription, i.e., the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen, would be important to know and adjust for, especially for oral drugs. Both adherence and persistence have been shown important for optimizing fracture outcomes [32, 33]. Finally, we did not retain hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in our selection of bone active substances, albeit it was shown to significantly reduce hip fracture risk by approximately one-third in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials [34, 35]. The WHI trials also showed a significant increase in breast cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and all-cause mortality which led to drastic reductions in systemic HRT use since 2002, now being mainly reserved to younger postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms [36, 37]. As the effect of HRT on hip fracture risk was shown having vanished three years after discontinuation [38], we consider that omitting HRT from our analyses should not be expected to alter the present observations and conclusions. Whether and to what extent changes in the HRT prescription patterns due to safety concerns that emerged during the observation period covered by the present analyses may have contributed to the observed slowing of the secular decrease in hip fracture incidence deserves further research.

Overall, the present study suggests that although multiple treatment options were made available over the past two decades, the treatment gap remains large and has even increased over the past decade. Case finding strategies which may have been neglected in the more recent past should be reassessed. Future research should focus on establishing instruments for measuring progresses made, including on more detailed datasets reporting drug usage by sex and indication.

Data Availability

Source data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

(1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 843:1–129

Lippuner K, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Rizzoli R (2009) Remaining lifetime and absolute 10-year probabilities of osteoporotic fracture in Swiss men and women. Osteoporos Int 20:1131–1140

Lippuner K, Rimmer G, Stuck AK, Schwab P, Bock O (2022) Hospitalizations for major osteoporotic fractures in Switzerland: a long-term trend analysis between 1998 and 2018. Osteoporos Int 33(11):2327–2335

Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB et al (1996) Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 348:1535–1541

Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R et al (2007) Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 356:1809–1822

Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR et al (2009) Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 361:756–765

Skjodt MK, Ernst MT, Khalid S et al (2021) The treatment gap after major osteoporotic fractures in Denmark 2005–2014: a combined analysis including both prescription-based and hospital-administered anti-osteoporosis medications. Osteoporos Int 32:1961–1971

Keshishian A, Boytsov N, Burge R, Krohn K, Lombard L, Zhang X, Xie L, Baser O (2017) Examining the treatment gap and risk of subsequent fractures among females with a fragility fracture in the US Medicare population. Osteoporos Int 28:2485–2494

Malle O, Borgstroem F, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Svedbom A, Dimai SV, Dimai HP (2021) Mind the gap: incidence of osteoporosis treatment after an osteoporotic fracture - results of the Austrian branch of the International Costs and Utilities Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study (ICUROS). Bone 142:115071

Iconaru L, Smeys C, Baleanu F et al (2020) Osteoporosis treatment gap in a prospective cohort of volunteer women. Osteoporos Int 31:1377–1382

Kanis JA, Norton N, Harvey NC, Jacobson T, Johansson H, Lorentzon M, McCloskey EV, Willers C, Borgstrom F (2021) SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos 16:82

Singer AJ, Liu J, Yan H, Stad RK, Gandra SR, Yehoshua A (2021) Treatment patterns and long-term persistence with osteoporosis therapies in women with Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) coverage. Osteoporos Int 32:2473–2484

Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, Dawson-Hughes B (2014) The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res 29:2520–2526

Lippuner K, Johansson H, Borgstrom F, Kanis JA, Rizzoli R (2012) Cost-effective intervention thresholds against osteoporotic fractures based on FRAX(R) in Switzerland. Osteoporos Int 23:2579–2589

Lippuner K, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Rizzoli R (2010) FRAX assessment of osteoporotic fracture probability in Switzerland. Osteoporos Int 21:381–389

Ferrari S, Lippuner K, Lamy O, Meier C (2020) 2020 recommendations for osteoporosis treatment according to fracture risk from the Swiss Association against Osteoporosis (SVGO). Swiss Med Wkly 150:w20352

Svedbom A, Ivergard M, Hernlund E, Rizzoli R, Kanis JA (2014) Epidemiology and economic burden of osteoporosis in Switzerland. Arch Osteoporos 9:187

Chotiyarnwong P, McCloskey EV, Harvey NC et al (2022) Is it time to consider population screening for fracture risk in postmenopausal women? A position paper from the International Osteoporosis Foundation Epidemiology/Quality of Life Working Group. Arch Osteoporos 17:87

Harvey NC, Kanis JA, Liu E, Vandenput L, Lorentzon M, Cooper C, McCloskey E, Johansson H (2021) Impact of population-based or targeted BMD interventions on fracture incidence. Osteoporos Int 32:1973–1979

Koller G, Goetz V, Vandermeer B, Homik J, McAlister FA, Kendler D, Ye C (2020) Persistence and adherence to parenteral osteoporosis therapies: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 31:2093–2102

Tremblay E, Perreault S, Dorais M (2016) Persistence with denosumab and zoledronic acid among older women: a population-based cohort study. Arch Osteoporos 11:30

Borek DM, Smith RC, Gruber CN, Gruber BL (2019) Long-term persistence in patients with osteoporosis receiving denosumab in routine practice: 36-month non-interventional, observational study. Osteoporos Int 30:1455–1464

Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM (2007) A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 18:1023–1031

Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson G (2012) Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis–where do we go from here? N Engl J Med 366:2048–2051

Rodan G, Reszka A, Golub E, Rizzoli R (2004) Bone safety of long-term bisphosphonate treatment. Curr Med Res Opin 20:1291–1300

Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE et al (2006) Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA 296:2927–2938

Watts NB, Chines A, Olszynski WP, McKeever CD, McClung MR, Zhou X, Grauer A (2008) Fracture risk remains reduced one year after discontinuation of risedronate. Osteoporos Int 19:365–372

Black DM, Reid IR, Boonen S et al (2012) The effect of 3 versus 6 years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res 27:243–254

Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK et al (2010) Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med 362:1761–1771

Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR et al (2001) Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 344:1434–1441

Harvey NC, McCloskey EV, Mitchell PJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Pierroz DD, Reginster JY, Rizzoli R, Cooper C, Kanis JA (2017) Mind the (treatment) gap: a global perspective on current and future strategies for prevention of fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int 28:1507–1529

Ross S, Samuels E, Gairy K, Iqbal S, Badamgarav E, Siris E (2011) A meta-analysis of osteoporotic fracture risk with medication nonadherence. Value Health 14:571–581

Imaz I, Zegarra P, Gonzalez-Enriquez J, Rubio B, Alcazar R, Amate JM (2010) Poor bisphosphonate adherence for treatment of osteoporosis increases fracture risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 21:1943–1951

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL et al (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:321–333

Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR et al (2004) Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:1701–1712

Heinig M, Braitmaier M, Haug U (2021) Prescribing of menopausal hormone therapy in Germany: current status and changes between 2004 and 2016. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 30:462–471

Crawford SL, Crandall CJ, Derby CA, El Khoudary SR, Waetjen LE, Fischer M, Joffe H (2018) Menopausal hormone therapy trends before versus after 2002: impact of the Women’s Health Initiative Study Results. Menopause 26:588–597

Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL et al (2008) Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA 299:1036–1045

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Alois Grüter, Associate Director IQVIA AG, Branch Rotkreuz, Switzerland, for kindly providing access to individual drug market data, and to Barbara Schär, Department of Osteoporosis and Philippe Kress, M.D., Kressmed, Oberembrach, Switzerland, for their contribution to data analysis and their critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bern. This work has been supported by an unrestricted research grant from Amgen Switzerland AG (Investigator Initiated Research Grant number 20197239).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to conception and design (KL and BYM) and/or analysis and interpretation of the data (KL, BYM, and PS) and/or important contributions to the manuscript (KL, BYM). All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This is not required by Swiss law for database analyses without individual patient data

Consent to participate

This is not applicable.

Conflict of interest

None was declared by BYM and PS. KL has served as an expert in advisory board meetings of Amgen Switzerland AG and UCB Pharma AG Switzerland.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lippuner, K., Moghadam, B.Y. & Schwab, P. The osteoporosis treatment gap in Switzerland between 1998 and 2018. Arch Osteoporos 18, 20 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-022-01206-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-022-01206-6