Abstract

Why do individuals in democratic nations sympathize with autocratic leaders from abroad? In this article, we address this general question with regard to Germans’ attitudes toward Vladimir Putin in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Building on the intuition that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” and its formalization in balance theory, our study focuses on the role of political alienation at home. To study this role comprehensively, we consider several facets of political alienation: a lack of trust in political institutions, low support for democracy as a regime, a sense of estrangement from public discourse, and an inclination toward conspiracy thinking. Using longitudinal analyses on data from the German Longitudinal Election Study panel, we provide empirical evidence consistent with our argument that political alienation—particularly in terms of low political trust and a proclivity for conspiracy thinking—drives sympathies for Putin and his regime. Against the backdrop of mounting attempts by Russia and other autocratic powers to influence discourses in Western societies via some segments of society, our findings illuminate one important source of sympathy for Putin and, potentially, foreign autocrats more broadly.

Zusammenfassung

Warum sympathisieren Individuen in demokratischen Ländern mit autokratischen Führern aus dem Ausland? In diesem Artikel befassen wir uns mit dieser allgemeinen Frage mit Blick auf die Einstellungen der Deutschen gegenüber Wladimir Putin nach dem russischen Einmarsch in die Ukraine im Februar 2022. Ausgehend von der Intuition, dass „ein Feind eines Feindes ein Freund ist“ und ihrer Formalisierung in der sozialpsychologischen Balancetheorie, konzentriert sich unsere Studie auf die Rolle politischer Entfremdung. Um diese Rolle umfassend zu untersuchen, betrachten wir mehrere Facetten der politischen Entfremdung: mangelndes Vertrauen in politische Institutionen, geringe Unterstützung für die Demokratie als Regime, ein Gefühl der Entfremdung vom öffentlichen Diskurs und eine Neigung zu Verschwörungsglauben. Anhand von Längsschnittanalysen mit Daten des GLES-Panels liefern wir empirische Belege für unsere These, dass politische Entfremdung – insbesondere in Form von mangelndem politischem Vertrauen und einer Neigung zu Verschwörungsdenken – Sympathien für Putin und sein Regime fördert. Vor dem Hintergrund der zunehmenden Versuche Russlands und anderer autokratischer Mächte, Diskurse in westlichen Gesellschaften über bestimmte Gesellschaftssegmente zu beeinflussen, beleuchten unsere Ergebnisse eine wichtige Quelle der Sympathie für Putin und, potenziell, ausländischer Autokraten im Allgemeinen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

On 24 February 2022, Russian military forces launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on orders issued by Vladimir Putin. Putin’s decision has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, caused Europe’s largest refugee crisis since the Second World War, and has led to extensive damages to civilian infrastructure and the environment. The Russian invasion of February 2022 was quickly and harshly condemned by overwhelming majorities of Germany’s political elite and public alike (see Mader and Schoen 2023, p. 531). Nevertheless, ever since the attack, a significant minority has expressed implicit understanding or even outright sympathies for Putin and his decision to launch the war. Such positions, often coinciding with Russian narratives, are frequently voiced in pro-Russian demonstrations across the country (N-tv 2022; Schmitz 2023), by fringe conspiracy groups (Lamberty et al. 2022b; Rathje et al. 2022), by politicians of the radical right Alternative for Germany (AfD; Schmidt 2022), and by parts of the country’s radical left (Pfaff 2022). Albeit being a clear (but sometimes loud) minority, the heterogeneous group of Putin and Russia sympathizers has attracted a considerable amount of public interest. Despite this, we still have little empirical evidence on who exactly holds these positions and why. More generally, there is little research on the broader puzzle of what makes citizens in democratic countries sympathize with autocratic leaders from abroad.

In this article, we aim to fill this gap and add to our understanding of who in Germany (still) sympathizes with Vladimir Putin and his regime. To do so, we systematize existent but scattered evidence from research on (1) which parties, and which parties’ voters, hold pro-Russian stances and (2) which individuals are susceptible to consuming and believing narratives from Russian information operations. By connecting these initial findings with psychological insights from balance theory (Heider 1958), which holds that humans strive for consistency in social relations, we derive our general argument: We expect that one of the main drivers behind individuals still holding sympathetic attitudes toward Vladimir Putin, one of the most prominent “enemies” of the German political system, is a profound sense of political alienation from said system. This alienation, we propose, manifests itself in feelings that go beyond low political support in the narrow sense of political trust and extend to an estrangement from democracy as a political order, a sense of detachment from public discourses, and an inclination toward conspiracy thinking. We test this expectation using panel survey data from the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES), drawing on data from before and after the invasion of February 2022.

Longitudinal regression analyses provide empirical evidence consistent with our argument. We first show that the more alienated individuals felt before the invasion, the more positively they view Vladimir Putin (and his regime) postinvasion, with all four facets of political alienation being substantially associated with holding more friendly attitudes toward Putin. To move further toward establishing a causal effect of political alienation, we then regress change in ratings of Putin in the wake of the invasion on preinvasion political alienation. Here, we obtain significant effects for three of the four facets of political alienation, with lack of political trust and conspiracy mentality—a potent manifestation of deep-seated distrust in societal and political elites—being especially consequential. We also present results for a combined measure of political alienation, documenting large overall effects on (change in) ratings of Putin that trump those of other variables, including individuals’ core postures on foreign policy and their ideological orientations.

This article makes several contributions to existing research as well as to ongoing public discussions. To begin with, we provide an explanation for the publicly debated puzzle of why some German citizens still sympathize with Putin. In doing so, we put forth an answer to the more general—but so far rarely studied—question of why people living in democratic societies may hold sympathetic attitudes toward foreign autocratic leaders and regimes. In times of increasing systemic rivalries between autocracies and democracies worldwide, this question is especially urgent to address. Our answer focuses on the role of political alienation because we believe that this is an important and novel perspective. At the same time, this study adds to our understanding of the nature and consequences of political alienation. More specifically, we provide a comprehensive conceptualization of political alienation, encompassing facets that go beyond mere political support, and empirically test its consequences for foreign policy attitudes.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: We begin by discussing previous research and its implications for attitudes toward the Putin regime. After that, we turn to our conceptualization of political alienation, propose a general mechanism linking it to sympathetic attitudes toward Putin, and—applying this mechanism to four different facets of political alienation—derive our four hypotheses. We then discuss data and methods before moving to the results. The final section presents our conclusions.

2 Previous Evidence on Attitudes Toward the Putin Regime

To the best of our knowledge, sympathies toward Putin and his regime have seldom been examined in a focused and systematic way, neither for Germany nor for other Western democracies. Thus, the main question of this article—who holds such sympathies and why—remains largely unanswered by the scientific community, despite growing public interest. More generally, there is little systematic research on the broader question of what leads individuals to sympathize with autocratic leaders from abroad that we could built on.Footnote 1

Nevertheless, we can draw on two related strands of research to formulate expectations about the attitudinal drivers of sympathetic views toward Putin: research on which parties, and which parties’ voters, take pro-Russian positions and research on individuals’ susceptibility to Russian information operations.

Studies from the first strand of research suggest that—while the positioning and behavior of individual parties are obviously subject to strategic considerations and specific contexts (Wondreys 2023)—pro-Russian and pro-Putin positions are especially prevalent among parties on the fringes of the political spectrum.Footnote 2 Albeit being otherwise ideologically heterogeneous, these parties and their electorates mainly seem to share system-critical, “anti-establishment,” and often radical positions (Fisher 2021; Golosov 2020; Hooghe et al. 2024; Onderco 2019). They are therefore sometimes fittingly coined the “fellow travelers” of the Kremlin’s general anti-Western and anti-democratic stances (Snegovaya 2022). In Germany, pro-Russian sentiments have accordingly been most prominent among the elites and electorates of both the populist radical right AfD and the radical Left Party (Die Linke; Mader and Schoen 2023, pp. 540–541; Olsen 2018, p. 77; Wood 2021, pp. 778–779, 781–784). Even after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, i.e., a time when strategic considerations seem especially likely to shape party positioning on Russia (Wondreys 2023), representatives of the AfD and, albeit to a lesser extent, the Left Party continued to publicly voice understanding or implicit support for the Russian regime (Arzheimer 2023; Pfaff 2022; Schmidt 2022; Wondreys 2023, pp. 4–5). With regard to attitudes toward Putin, in particular the voters of populist radical right parties have been shown to hold relatively positive attitudes (Huang 2020; Letterman 2018; Silver and Morcus 2021; Wike et al. 2022).

Accordingly, existing research has paid special attention to the sympathies toward the Putin regime prevalent among large parts of the Western radical right, identifying an authoritarian–nationalist rejection of the liberal order as an important ideological similarity (Michael 2019; Wondreys 2023, p. 2). However, while ideological similarities might well play a role in driving sympathies toward Putin among parts of the radical right, they often seem to take a back seat against strategic considerations and contextual specifics shaping party positioning on Russia (Wondreys 2023). More important, they seem insufficient to fully explain sympathies for the Putin regime, especially among culturally less authoritarian parties and their electorates.

A second line of research focuses on the reach and impact of messages that disseminate pro-Russian and related anti-Western narratives among citizens in Western democracies. The Kremlin actively spreads such narratives to polarize and destabilize political discourses and to exert influence on specifically targeted segments of society (Pomerantsev 2016; Snegovaya and Watanabe 2021). Results from these studies point in a similar direction: These narratives are mainly consumed and believed among individuals sharing an alienation from the current political system. This alienation manifests itself in low political trust and low satisfaction with democracy, fringe political ideologies, or a broader conspiracy mentality (e.g., Helmus et al. 2020; Hjorth and Adler-Nissen 2019; Radnitz 2022; Snegovaya and Watanabe 2021). In survey experiments fielded in Germany, for example, Mader and colleagues have shown that citizens “who are estranged from today’s liberal democracies” (Mader et al. 2022, p. 1734) are more likely to be influenced by pro-Russian or anti-Western narratives originating from Russian sources. Likewise, observational studies indicate that pro-Kremlin disinformation and narratives are most widespread among Germans showing signs of political alienation (Lamberty et al. 2022a; 2022b; Rathje et al. 2022; Smirnova and Winter 2021; Smirnova et al. 2022).

Taken together, these pieces of evidence allow formulation of a general expectation about who takes Putin-friendly positions in Germany (and in other Western democracies as well): These attitudes should be especially prevalent among individuals who, for different reasons, are alienated from their democratic systems. This political alienation manifests itself in a feeling of deep-seated disenchantment from the political system, its mainstream elites, and its discourses.

3 The Role of Political Alienation

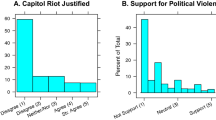

But how is this political alienation linked to Putin-friendly attitudes? We build our theoretical argument on psychological insights from balance theory (Cartwright and Harary 1956; Heider 1958). Balance theory holds that humans strive for consistency in social relations, and, in this sense, it can be seen as one application of the broader theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957). The idea of balance can be applied to triads involving two persons and an impersonal entity or to relationships among three actors (or more). A triad of three persons A, B, and C is in balance when all three hold positive relations with one another—reflecting the familiar idea that “a friend of a friend is a friend.” From the perspective of person A, balance will also be achieved when she dislikes B, B has a conflictual relation with C, and A likes C (Fig. 1). This captures the common saying that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Experimental psychological research has shown that we humans indeed react in this way and will come to “like someone who dislikes someone we dislike” (Aronson and Cope 1968, p. 12). Relatedly, research on the political domain indicates that individuals who view their political system as illegitimate view (domestic) violators of said system’s norms more positively (Hahl et al. 2018). Balance theory has also been employed to understand networks of relations between domestic and foreign political actors (see Kinne and Maoz 2023).

We propose that balance logic provides a useful theoretical foundation to understand the formation of Germans’ orientations toward Putin (and, potentially, toward rival autocrats more broadly). Balance theory suggests a straightforward and intuitive mechanism for why Putin might appeal to politically alienated individuals in Germany (and elsewhere), shown graphically in Fig. 1. Accordingly, individuals alienated from the German political system may think of Putin (and, along with him, his regime)—himself an apparent “opponent” of the system they do not support—as an ally in their alienation and subsequently feel more positively toward Putin and his regime. This “enemy of my enemy is my friend” logic seems particularly well suited to explain why otherwise ideologically heterogeneous groups on the fringes of the political spectrum hold more positive views toward Putin and his regime. Naturally, balance logic can also be applied in reverse, following an equally simple “the enemy of my friend is my enemy” logic: Individuals who feel strongly attached to the current German political system and its elites should be inclined do dislike Putin, as he is perceived as a symbol of opposition or even outright threat to the system they approve of. Whereas Putin had been in low-level conflict with the German political system even before the attack on Ukraine in February 2022, our balance argument seems especially likely to hold true after the attack. The subsequent war made Putin and his regime a clearly visible and more threatening opponent of the German political system. Thus, we expect political alienation to be especially consequential for attitudes toward Putin after the invasion. At the same time, this means that intraindividual changes in attitudes toward Putin in response to the war should be contingent on levels of political alienation. Whereas attitudes toward Putin likely worsened significantly among those with low levels of political alienation, such downward adjustment should be less likely the higher an individual’s level of political alienation. In fact, some of the most strongly alienated individuals may have updated their views of Putin into a positive direction in response to him becoming a more visible opponent of the German political system.

Although the presented evidence on the possible drivers of Putin- and Russia-friendly positions points in this direction, and a simple mechanism is able to explain the linkage, to our knowledge no substantial attempts have been made at conceptualizing the kind of political alienation that could play a role for sympathetic attitudes toward Putin and his regime. We suggest that a fruitful starting point for doing so is the well-established concept of political support (Easton 1975). Drawing on the conceptual differentiation between more diffuse and more specific forms of support, political alienation may take different forms as well. In addition to “diffuse” support for democracy as a regime and trust in specific institutions that are core aspects of political support (Norris 2017), our conceptualization integrates additional, and in a way even more deep-seated, forms of political alienation, i.e., feelings of alienation from public discourse and an inclination toward conspiracy beliefs. As our theoretical framework extends beyond classic indicators of the established concept of political support, we refer to political alienation as our broader umbrella concept.

At the core of our conceptualization of alienation lies a lack of political trust. Understood as a core feature of lacking support for more specific elements of the political system, especially its core institutions, this kind of alienation tends to be relatively widespread in democratic societies (Dalton 2004; Norris 1999). We expect a lack of political trust to be highly consequential for sympathies toward Putin: Following the “enemy of my enemy is my friend” logic, apparent opponents of the distrusted system should appear more sympathetic to politically alienated individuals. This is especially likely to be the case in Germany after the outbreak of the war: As discussed, Putin immediately became one of, if not the most prominent political actor in apparent conflict with the German political system. This fact alone may well be reason enough for some citizens to hold sympathies for the opponent of the system they no longer trust. In contrast, those with high trust in German political institutions are likely to perceive Putin as an enemy of the system they do support. These trusting individuals likely followed and accepted mainstream elites’ messages that—outlining how Putin launched an unjust and unprovoked war of aggression and was responsible for war crimes—cast him into a decidedly negative light.

Moreover, low political trust has been shown to oftentimes correlate with low support for incumbent parties as well as voting for populist and protest parties on both fringes of the political spectrum (Hooghe 2017, pp. 623–624; Hooghe and Dassoneville 2018; Norris and Inglehart 2019, pp. 284–286). As discussed above, these parties and their electorates often take sympathetic stances toward Russia and Putin, despite their different ideologies. Our argument is able to make sense of this pattern: It suggests that a lack of support for the existing political order is the common root of such sympathies for the Putin regime.Footnote 3 We thus formulate our first hypothesis:

H1:

The lower one’s political trust, the more positive the attitude toward Putin.

Going beyond a lack of trust in institutions, political alienation can also manifest itself in a lack of support for more diffuse elements of the German political system, i.e., its democratic ideals, ideas, and norms. Diffusely alienated individuals may call into question these foundations of democratic governance and, openly or more subtly, prefer autocratic alternatives. Applying the logic from above to diffusely alienated individuals is again straightforward: Their rejection of democratic governance should make Russia, one of the most prominent and well-known autocratic systems, an “ally” in their alienation and an attractive alternative to the democratic system they do not support. Putin, as the face and heart of the Russian regime, should act as a symbol for the rejection of (liberal) democracy. Intuitively, the more open to authoritarian rule individuals are, the more lenient their assessment of the autocratic Putin regime should be. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

The lower one’s support for democracy as a regime type, the more positive the attitude toward Putin.

Alienation from the political system may well extend to a feeling of disconnect from the mainstream public discourses within that system. Such a disconnect could manifest in a feeling of one’s views entirely lacking representation in mainstream discourses. Individuals who feel alienated in this way may more readily discount or ignore messages from the mainstream public debate. For attitudes toward Putin after the war, this feeling of disconnect from societal discourse should be particularly relevant as well. So far, public discourse on the war in Germany has been dominated by strong stances against Putin and the war in Ukraine as an act of aggression by his regime (cf. Mader and Schoen 2023). Previous research has shown that negative (positive) media coverage of foreign countries and their leaders can negatively (positively) influence attitudes toward the portrayed countries among recipients (Balmas 2018; Brewer et al. 2003; Ingenhoff and Klein 2018). Nonalienated individuals are therefore likely to have accepted the mainstream media’s decidedly negative framing of Putin. Following balance logic, such an effect seems considerably less likely among alienated individuals. On the contrary, a feeling of disconnect from mainstream discourse could translate into a feeling of disconnect from the positions articulated in it. It is therefore plausible that politically alienated individuals—who feel they are no longer part of mainstream discourse—are most likely to be unmoved by respective information and messages and are even inclined to feel sympathy for the portrayed enemies within said discourse. As a third hypothesis, we therefore expect the following:

H3:

The more alienated one feels from public discourse, the more positive the attitude toward Putin.

So far, we have covered three mostly passive facets of political alienation: manifestations that center on a lack of (1) trust in the system, (2) support for its democratic norms, and (3) identification with its mainstream discourses. However, alienation can also manifest as an even more active, deep-seated, and wide-ranging distrust toward political and societal elites in general. Distrust of this kind is different from the already discussed lack of political trust in that it entails not only a lack of positive expectations and feelings toward the system but explicitly negative ones (Bertsou 2019). A potent and often discussed manifestation of this wide-ranging distrust is an inclination toward conspiratorial beliefs, or a “conspiracy mentality”—understood as “the general propensity to subscribe to theories blaming a conspiracy of ill-intending individuals or groups for important societal phenomena” (Bruder et al. 2013, p. 2). This worldview suspects events to be caused by secret plans of powerful elites and is predictive of beliefs in more specific conspiracy theories (Imhoff et al. 2022). We follow the view that a conspiracy mentality constitutes a generalized political attitude, with the readiness to blame current high-power groups for negative events and outcomes being a manifestation of a deep-seated distrust in these elites (Imhoff and Bruder 2014; Uscinski et al. 2021).

Having a conspiracy mentality seems highly relevant for attitudes toward Putin, especially after the war. Individuals with a strong conspiracy mentality should not only be more likely to attribute blame for the war and its negative consequences to current German and Western elites, but they may also take the mere fact that these elites in large part condemn the attack on Ukraine as a reason to believe conspiratorial counternarratives. Individuals with a conspiracy mentality are especially likely to be more receptive to counternarratives on the war provided by the Kremlin as part of its information operations, which will, in turn, shape their views on the war and their attitudes toward Putin. Indeed, survey experimental results of Mader et al. (2022) show that anti-Western propaganda messages resonate (only) among Germans who score high in conspiracy theory beliefs, and observational findings reveal that Russian narratives about the war in Ukraine are widespread within the German conspiracy scene (Lamberty et al. 2022b; Rathje et al. 2022). Thus, our fourth and final hypothesis is as follows:

H4:

The stronger one’s inclination to believe in conspiracies, the more positive the attitude toward Putin.

We focus our analysis on the role of political alienation, as we believe that this perspective is not only novel but also very well suited to explain Putin-sympathies of an otherwise heterogeneous minority in Germany. However, this focus is not to disregard other possible causes of sympathy for Putin and his regime. Another important driver of attitudes toward another country’s leader and regime might be people’s general foreign policy orientations. Existing research shows that these core postures significantly shape how individuals think about their country’s foreign policies, including its relations to other international actors (Hurwitz and Peffley 1987; Mader 2015). In the German context, four core postures of this kind are typically distinguished: general attitudes on the extent of one’s country’s international involvement (isolationism vs. internationalism), general attitudes on cooperation with other countries and international actors (unilateralism vs. multilateralism), general attitudes on the role and legitimacy of military means as a tool in international relations (militarism vs. pacifism), and general attitudes on transatlantic cooperation with the United States (Atlanticism vs. anti-Atlanticism; Mader 2015; Mader and Schoen 2023, p. 529). We expect these postures to shape attitudes toward Putin and his regime as well and therefore include them in our empirical models. More precisely, we expect pacifists, multilateralists, internationalists, and pro-Atlanticists to view Putin less positively, as he clearly acts as an antipode to associated international norms.

Another possible string of explanations includes ideology-related reasons for sympathies toward Putin. For instance, cultural grievances and their linkage to specific anti-Western and antiliberal narratives the Russian regime refers to could well play a role too (Onderco 2020), as already discussed regarding the Western radical right’s ideological similarities with the Putin regime (Michael 2019). In our view, such explanations are at least partially compatible with our argument that these kinds of ideological grievances may trigger feelings of political alienation, which then act as more proximate causes of pro-Putin views. Nevertheless, we control for whether individuals hold “authoritarian” or “traditionalist” policy positions and for whether they locate themselves at an extreme end of the political spectrum, as Putin’s appeal might also be directly related to holding such positions.

4 Data and Methods

Our empirical analysis draws on the panel survey of the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES). The GLES Panel is an online panel survey designed to represent those eligible to vote in German national elections, with quotas for age, sex, and education. For our analysis, we considered data up to wave 24, carried out in May 2023.Footnote 4 For all analyses, we used a weight adjusting the sample of wave 21 to the German microcensus of 2019.

Our main outcomes of interest are respondents’ attitudes toward Vladimir Putin. These attitudes were captured as part of a battery in which respondents were asked, “In general, what do you think of the following countries and politicians?” Respondents could choose their answers from a scale ranging from +5 (“I think much of him”) to −5 (“I think nothing of him”). This item allows us to capture precisely the kind of overall assessment of Putin that we are interested in, rather than evaluations of more specific traits, e.g., his personality or leadership skills. In additional analyses, we will consider ratings of Russia, drawn from the same battery, and a broader composite measure of attitudes toward the Russian regime to triangulate our findings on the determinants of attitudes toward Putin personally.

In our main analysis, we focus on ratings of Putin as measured in wave 24 of May 2023. We turn to wave 24 rather than earlier ones for three reasons. First, we are interested in who still had favorable views of Putin after his decision to launch the reinvasion. Second, we prefer measuring attitudes toward Putin not in the early phase of the war, when attitudes might have been more transitory in consequence of a temporary shock, but at a later stage, when these are more likely to have been consolidated. Third, we prefer to use the most recent data available at the time of writing to speak to the current public debate.

Our empirical strategy seeks to leverage the longitudinal nature of the data to address concerns of reverse causality. It is possible that individuals’ reactions to the events around the Russian invasion affected their level of political alienation: Individuals who sympathize with Putin might have become more alienated from the German political and societal mainstream in response to the broad condemnation of the Russian war of aggression; that is, sympathy for Putin might have led to political alienation. To deal with this, we regress postinvasion ratings of Putin on independent variables as measured before the invasion began. Specifically, we took the independent variables, including the control variables, from wave 21 of December 2021 or the latest wave before that in which they had been included.

In a first set of models, we regress levels of (postinvasion) ratings of Putin on preinvasion predictors. These models straightforwardly address our main question of who still sympathizes with Putin after Russia’s full-scale invasion. To this end, we estimated both ordinary least squares (OLS) and binary logistic regressions. For the OLS regressions, we simply used the numerical Putin rating (−5 to +5) as an outcome variable. For the binary logistic regressions, we used a dichotomous indicator of support for Putin that codes all negative answers (−5 to −1) as 0 and all neutral and positive ones as 1. While the numerical rating has the advantage of using all the variation, including variation in the degree of dislike of Putin, the logit model allows us to focus on what divides those who do not view Putin negatively from those who do.

In a second set of models, we regress change in ratings of Putin on preinvasion predictors. To do so, we computed the difference in individuals’ ratings of Putin in May 2023 vs. December 2021 and estimated OLS regression with this outcome variable. With a mean of −1.45, ratings of Putin worsened on average. But with a standard deviation of 2.45, there is still a lot of variation. While ratings of Putin deteriorated among 54.3% of respondents, 6.7% gave even a higher rating of Putin in May 2023 than in December 2021 (Fig. A1 in the online appendix). Via these models, we asked whether (preinvasion) political alienation is predictive of how respondents updated their views of Putin in response to the Russian invasion. Our theoretical argument suggests that the deterioration in ratings of Putin we observe was concentrated on average among individuals with low levels of political alienation. Thus, the more politically alienated an individual was preinvasion, the less negative (or more positive) the value should be on the difference variable. By studying variation in Putin ratings within individuals over time, we aim to move an additional step closer toward establishing a causal effect of political alienation on ratings of Putin. At the same time, by looking at only the difference, these estimations do not take into account that politically alienated individuals might have already viewed Putin more positively before the Russian invasion of February 2022 and to some degree just continued to do so. For this reason, we present results from both the level and the change models. We estimated all regression models with robust standard errors.

Our central independent variables are measured as follows, with further details listed in Online Appendix A. We measure lack of political trust in German institutions by absence of trust in the Bundestag, the federal constitutional court, and public broadcasting (each recorded on a five-point scale). While deliberatively covering different types of institutions, as is common when measuring political trust (Marien 2017), the three trust items load well on a single scale. We use their reversed mean as an encompassing measure of lack of political trust. Lack of diffuse support for democracy is captured via an item that asks for agreement with the statement “Under certain circumstances, dictatorship is a better form of government,” recorded on a five-point scale. To measure alienation from public discourse, we draw on agreement with the statement “People like me are no longer allowed to express their opinions freely in public.” Finally, conspiracy mentality is measured by four items following Imhoff and Bruder (2014), with an exemplary item stating that “Most people do not recognize to what extent our lives are determined by conspiracies hatched in secret.” We used the mean agreement with the four (highly correlated) statements. All four measures were recoded to range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater political alienation.

Distributions and pairwise correlations of these variables are shown in Online Appendix A. Notably, alienation from public discourse and, especially, lack of support for democracy are right skewed, with few respondents (fully) agreeing with the statements. The four measures all correlate positively with one another. However, these correlations are not exceedingly high, hovering between 0.20 and 0.55, corroborating that the items do in fact measure related but still separate facets of a broader political alienation. To also capture this broader political alienation through a single measure, we combined the four measures described above through factor analysis (Table A3 in the online appendix). With loadings between 0.77 and 0.81, the measures load strongly on a single scale, with only lack of support for democracy exhibiting a somewhat weaker loading (0.54). While we will primarily rely on the separate measures to test our individual hypothesis (H1 to H4), we will also present results with the combined factor score. This is useful because it readily gives us information on the overall effect of political alienation. At the same time, we address the concern that the correlations between the different facets of political alienation might make it challenging to establish their individual effects.

For sociodemographic control variables, we include sex, education, a dummy for whether respondents speak Russian at home, age group, residence in eastern Germany, and—to capture possible effects of socialization in the German Democratic Republic—the interaction between the latter two variables. As further rival explanations of holding sympathies for Putin, we consider foreign policy orientations, authoritarian policy positions, and left–right positions. Following Mader and Schoen (2023), we constructed mean indices of (anti‑)Atlanticism, isolationism, unilateralism (the reverse of multilateralism), and pacifism. To measure authoritarian policy positions, we include a factor capturing a preference for a restrictive immigration policy, opposition to measures for gender equality, and opposition to climate protection. Finally, we distinguish between an extreme left, a left, a centrist (reference category), a right, and an extreme right self-placement on the left–right scale. Again, we measured all these variables before the invasion (i.e., wave 21 or earlier) to avoid endogeneity problems and rescaled them to range from 0 to 1 to ease model interpretation.

In the models for change in ratings of Putin, we additionally control for individuals’ preinvasion ratings of Putin, as measured in wave 21. This is crucial to capture regression-to-the-mean effects that stem from the bounded nature of the rating scale. The potential for decreases in ratings of Putin was by design much greater when individuals initially rated him as favorable. For respondents who had already rated him at −5, no further decrease was possible. This relationship is captured well by including the lagged level of the Putin rating as a linear and squared term in the regression equation (see the scatterplot in Fig. A2 of the online appendix).

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive Results

We begin our empirical investigation with a descriptive look at ratings of Putin over time. In Fig. 2, we show how respondents rated Putin in December 2021 and May 2023. While Germans overwhelmingly held negative views of Putin even before the invasion of February 2022, the ratings had markedly deteriorated in May 2023. Still, 13.5% of German respondents viewed Putin at least neutrally in May 2023, with 6.3% indicating a positive rating.Footnote 5

Figure 3 provides first insights into the role of political alienation. It shows mean ratings of Putin over time in groups with different levels of political alienation, measured via the four indicators. In all waves and for all indicators, there is a sizable gap in mean ratings of Putin between individuals with lower vs. higher levels of political alienation. Unsurprisingly, attitudes toward Putin became more negative in every group after the Russian invasion of February 24, 2022. As to the size of the decreases, the much higher preinvasion levels within the alienated groups imply that the potential for decreases in ratings of Putin was much larger in these groups. Despite this, there is no pattern of convergence. In the case of lack of political trust, and more tentatively for conspiracy mentality as well, the gap even became notably larger over time: The difference in means between those with high and low lack of political trust increased from 1.1 in December 2021 to 1.7 in May 2023. In Fig. A3 of the online appendix, we show that a similar tendency applies to ratings of Russia: These also deteriorated during the invasion, and the difference in means between individuals with high and low lack of political trust widened from 0.6 preinvasion to 1.4 in May 2023.

Mean rating of Putin across waves and facets of political alienation. Observations held constant over time. Political alienation variables are measured preinvasion and collapsed into three categories as follows. Lack of political trust and conspiracy mentality—high: values ≥ 0.75; medium: > 0.25 and < 0.75; low: values ≤ 0.25. Lack of support for democracy and alienation from public discourse—high: (partly) agree that dictatorship might be better/that people like me are no longer allowed to freely express opinions; medium: neither; low: (partly) disagree

These descriptive patterns support previous findings of a considerable negative turn in public opinion toward Putin and Russia after the attack (Graf 2022; Wike et al. 2022). However, several studies in the immediate aftermath of the attack found indications of a growing convergence in negative views between individuals positioned on the left and right of the ideological spectrum as well as supporters of different parties in several Western societies (e.g., Asadzade and Izadi 2022; Bordignon et al. 2022; Poushter and Connaughton 2022; Wike et al. 2022; for an exception, see Mader and Schoen 2023, pp. 539–541). However, convergences have not occurred between groups with different levels of political alienation in Germany. This is another hint that political alienation may play a crucial role for sympathetic stances toward the Putin regime.

5.2 Regression Analysis of Levels of Ratings of Putin

In Fig. 4, we present the results of our first set of regressions for levels of (postinvasion) ratings of Putin in May 2023. The left-hand side presents coefficients from OLS regressions using the gradual Putin rating as an outcome variable. The right-hand side shows—using the binary indicator as an outcome—average marginal effects on the probability to view Putin favorably, calculated from binary logistic regressions. In both panels, we present results for our main specification (in blue or, in the print version, dark gray) alongside results for a specification with the combined political alienation factor instead (in orange or, in the print version, light gray).

Predicting ratings of Putin in May 2023. Left-hand side: Coefficients from ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with 95% (thick) and 90% (thin) confidence intervals. Right-hand side: Average marginal effects (AMEs) with 95% (thick) and 90% (thin) confidence intervals from binary logistic regressions (outcome variable: Putin rating of −5 to −1 coded as 0; Putin rating of 0 to +5 coded as 1). Pseudo‑R2 on the right-hand side refers to McKelvey and Zavoina. All independent variables scaled from 0 to 1. N = 6820

All four facets of political alienation are positively associated with more positive views of Putin, both in the OLS and the logit model. As hypothesized, the more someone feels politically alienated, the higher their rating of Putin, or respectively, the higher the probability that they have a neutral-to-positive view of Putin. According to the OLS model, moving from the low to the high end of political alienation increases predicted ratings of Putin by 1.3 for lack of political trust (H1), by 0.6 for lack of support for democracy (H2), by 0.5 for alienation from public discourse (H3), and by 1.0 for conspiracy mentality (H4). Similarly, according to the logit model, the predicted probability of a neutral-to-positive stance toward Putin increases by 14 percentage points for lack of political trust, by 7 percentage points for lack of support for democracy, by 4 percentage points for alienation from public discourse, and by 11 percentage points for conspiracy mentality. Importantly, these effects may add up when individuals feel alienated along more than one facet.

The large overall effect of political alienation is illustrated by results from the second specification based on the combined factor score (which we also rescaled to range from 0 to 1). Accordingly, moving from the low to the high end of political alienation is associated with an increase in 3.2 points in the rating of Putin (OLS model) and of 35% in the probability of a neutral-to-positive view of Putin (logit model). The average predicted probability of viewing Putin as friendly is 2.5% when setting political alienation to 0, while it is 50.5% when setting political alienation to 1.Footnote 6 If we set political alienation to its 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile values, we get probabilities of 3.3%, 7.9%, and 22.1%, respectively.

From the sociodemographic control variables, speaking Russian at home stands out, though with a large margin of error due to the small number of Russian speakers. While lower education is associated with more Putin-friendly views in a model with only sociodemographics (Fig. B1 in the online appendix), these associations largely disappear when accounting for political alienation. In addition, Putin is viewed more positively among younger respondents and by eastern Germans (of all age groups). Of the foreign policy postures, rejecting multilateralism (i.e., unilateralism) and cooperation with the United States (anti-Atlanticism) as well as a preference for Germany to focus on its domestic problems (isolationism) are associated with rating Putin more positively, as expected. Pacificism exhibits a weaker effect and, if anything, is associated with more positive ratings of Putin. Paradoxical as it is, we reason that pacifists may be more hesitant to take confrontational attitudes toward an obviously violent dictator out of heightened fears of military escalation. In addition, holding more authoritarian policy positions is associated with rating Putin more favorably. Even conditioning on all these covariates, self-placements at the extreme right-wing remain associated with more positive views of Putin, whereas there is no such tendency for the extreme left.

In Online Appendix D, we show that one obtains similar results when considering attitudes toward the Putin regime more broadly. To that end, we draw on six items from wave 23 (October–November 2023), including ratings of Putin and Russia and policy orientations toward the relationship with them. Using the resulting factor score as a measure of attitudes toward the Putin regime at large leads to very similar results as when we solely look at ratings of Putin personally. As shown in Online Appendix F, results are also similar when using ratings of Putin in waves 22 (May–July 2022) and 23 (October–November 2022) instead of those from wave 24 (May 2023). In all these additional models, we find all four political alienation variables to be significantly associated with Putin-friendly views, with lack of political trust in particular and also conspiracy mentality exhibiting somewhat larger effects. Moreover, we consistently find large overall effects of political alienation when using the combined factor.

5.3 Regression Analysis of Change in Ratings of Putin

In a next step, we turn to change in ratings of Putin during the war, calculated as the difference between postinvasion (wave 24) and preinvasion (wave 21) ratings of Putin. Again, we show results for our main specification with the individual indicators of political alienation (in blue or, in the print version, dark gray) and from a specification with the combined measure of political alienation (in orange or, in the print version, light gray). The coefficients from the OLS regressions are shown in Fig. 5. The four alienation variables are all positively signed, and three of them exhibit statistically significant effects—with lack of political trust showing the largest effect, followed by conspiracy mentality and then alienation from public discourse.

Predicting change in ratings of Putin between December 2021 and May 2023. Coefficients from ordinary least squares regressions with 95% (thick) and 90% (thin) confidence intervals. All independent variables scaled from 0 to 1, except for preinvasion rating of Putin in wave 21 (measured on a scale from −5 to +5). N = 6773

Given that ratings of Putin deteriorated on average (Fig. 2 and Fig. A1 in the online appendix), it is more natural to think about how the predictors prevent a downward adjustment of attitudes toward Putin, rather than to think about how they tend to increase the amount of upward adjustment.Footnote 7 This downward adjustment was, on average, 1.3 scale points smaller among those completely lacking political trust (compared to those with maximum trust), 0.55 scale points smaller for those with maximum values on conspiracy mentality (compared to those with minimum values on conspiracy mentality), and 0.22 scale points smaller among those fully agreeing that people like them would no longer be allowed to freely express their opinions in public (compared to those not agreeing at all).

Again, the effects may accumulate when individuals score high on more than one measure of political alienation. To illustrate the overall effect, we turn to the specification with the combined measure. Setting political alienation to 0 and 1, respectively, we obtain predicted values of −2.2 and −0.1, with the latter not being statistically different from 0. If we set political alienation to its 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile values, we obtain predicted values of −2.1, −1.6, and −0.9, respectively. These results indicate that the less (more) politically alienated individuals felt before the invasion, the more (less) their rating of Putin deteriorated after the invasion.

Still, even more so than in the level models, the facets of political alienation seem to matter to different degrees. The effect is clearly largest for lack of political trust, as the perhaps most obvious and direct expression of political alienation. We also obtain a substantial effect of conspiracy mentality as an expression of active distrust in political and societal elites. We reason that these two variables play a particularly vital role in shaping how people updated their views of Putin during the war because they influence most strongly whether citizens align with and are swayed by mainstream messages concerning the events, as well as their openness to believe counternarratives. Although the same could be said about alienation from public discourse, its smaller effect may reflect that this measure is based on just a single item and correlates substantially with lack of political trust and conspiracy mentality.Footnote 8 In contrast, the absent effect for lack of support for democracy in the change model seems to indeed indicate that diffuse support for democracy was not particularly relevant for how individuals updated their views of Putin in light of the Russian invasion. However, low support for democracy had already been strongly associated with more positive ratings of the autocrat Putin before the invasion and, given persistence in ratings of Putin, continues to be thus associated thereafter (Fig. 4).

Overall, though, we can conclude that political alienation before the invasion is strongly predictive of how views toward Putin evolved in the wake of the Russian invasion. In contrast, few of the attitudinal controls are predictive of change in ratings of Putin. The only statistically significant finding is that the stronger the preference for multilateralism over unilateralism, the larger the downward adjustment in the rating of Putin.

Again, we conducted several robustness checks. First, we introduced party identification, measured preinvasion, as an additional control variable (Online Appendix E). We find that identifying with the AfD is associated with a less negative change in ratings of Putin by about 0.7 scale points, likely as a reaction to the cues sent out by the party (see Arzheimer 2023). Most important, however, our main results remain similar, suggesting that individuals updated their views mainly in response to their own feelings of political alienation and not just in response to party cues. Second, we looked at change in ratings of Russia instead (Online Appendix D). The results are similar, although in this case all four alienation measures are statistically significantly associated with more positive (less negative) changes in ratings. Third, we studied change in ratings of Putin for the earlier postinvasion waves (Online Appendix F). Again the results are similar, although the effects tend to get slightly weaker the less time we give for opinion updating to take place.

6 Conclusion

Ever since Vladimir Putin’s decision to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022 there has been considerable public interest in the question of why a heterogeneous minority of Germans continued to voice understanding or even sympathies for the Putin regime. In this study, we have proposed an answer that centers on the role of political alienation, arguing that citizens who are alienated from the German political system, from democracy itself, and from public discourse and who are inclined to believe in conspiracy theories are most likely to (still) hold sympathetic views toward Putin and his regime. Theoretically, we have grounded our argument in balance theory, proposing that a simple mechanism of cognitive dissonance reduction according to which an enemy of an enemy is a friend can account for why politically alienated citizens sympathize with Putin—and nonalienated individuals dislike Putin.

Drawing on the GLES Panel that brackets Russia’s full-scale invasion of February 2022, we have provided empirical evidence in line with our expectation from two sets of longitudinal analyses. First, we have linked political alienation measured before the invasion to postinvasion ratings of Putin and have shown, in line with our hypotheses, that all four facets are significantly predictive of more positive ratings. Second, we have tested whether political alienation measured before the invasion also predicts how ratings of Putin changed during the Russian invasion, expecting that politically alienated individuals saw less reason to adjust their views of Putin downward—or that some even saw reasons for an upward adjustment. Here, we found three of the facets of political alienation to be significantly associated with smaller downward (or larger upward) adjustments in ratings of Putin: Those alienated from public discourse, lacking in political trust, and having a conspiracy mentality were less likely to adjust their rating of Putin significantly downward, with the latter two variables playing a bigger role. We also showed that our findings extend to attitudes toward the Russian regime as a whole and hold for several other robustness checks. Overall, our results comprehensively point to political alienation as one important motive for why German citizens (still) sympathize with Putin.

Despite this significance, our study is not without limitations and may be extended in several ways. Most important, we have focused on four central facets of political alienation that we suspected to be especially consequential given evidence from related research, but there may be others that also matter. These may be considered in future research. At some point, though, it becomes difficult to disentangle the separate impact of different facets of political alienation given their empirical interrelation and that similar mechanisms are likely to apply to them. Although we could establish distinct effects of a lack of political trust and conspiracy mentality here, for example, it deserves again to be noted that these attitudes tend to go together (r = 0.47 in our study) and that we obtained the strongest results when condensing all four facets into one comprehensive measure of political alienation. In our view, the most important follow-up questions are whether and how our argument and findings travel to other contexts. Therefore, we especially encourage future research to probe our argument in other national contexts or on attitudes toward other autocratic regimes and their leaders.

For now, our results establish a link between political alienation and sympathy for an autocratic leader abroad. The alienation prevalent in some segments of the German population seems to affect not only attitudes immediately related to national political matters but political worldviews that go beyond the national arena. As the conflict between the Putin regime and the democratic world continues, already alienated individuals sympathizing with Putin and his regime could become increasingly discontent and detached from mainstream politics. More broadly, this could add to existing polarization, not only on issues specifically pertaining to Russia but on political matters more generally. This possibility seems especially relevant against the backdrop of increasing attempts by Russia and other autocratic powers to influence precisely these alienated segments of the population in democracies, making use of disinformation and narratives specifically tailored to target existing feelings of alienation. Sympathies toward the Russian regime might well make targeted segments of the population even more susceptible to influence by these attempts (Soares et al. 2023). The results of this study indicate that dealing with this global challenge is one of many good reasons to better understand and address rising political alienation at home.

Notes

To be sure, there are some studies on attitudes toward foreign leaders and, more broadly, countries. However, this body of literature has tended to focus on variation at the aggregate level, that is, variation in overall attitudes toward different leaders (e.g., Goldsmith et al. 2021) and countries (e.g., Nincic and Russett 1979), whereas our argument is concerned with variation in attitudes toward one autocratic leader within one country across individuals. One important finding of this literature is that (perceived) similarity between countries is associated with more positive attitudes (Nincic and Russett 1979; Tims and Miller 1986) and that, more generally, in- vs. out-group psychology plays an important role in shaping those (e.g., Johnston Conover et al. 1980). The argument we develop accords with this general view. Seen from this perspective, our balancing argument holds that those who feel attached to the in-group of the domestic political “mainstream” will come to view its foreign adversaries as an out-group and assess it negatively, whereas this will be not the case for alienated individuals who do not feel part of this in-group in the first place. Having pointed out these general parallels to this broader literature, we proceed by reviewing studies more narrowly focused on the case of Putin and contemporary Russia.

Much of this existing research focuses on stances toward the country of Russia rather than its political system or leadership specifically. However, as we show, attitudes toward Putin, his regime, and Russia correlate strongly, allowing us to derive general expectations from these results as well.

For related evidence at the party level, see the recent study by Hooghe et al. (2024). These authors show that an anti-establishment orientation accounts for much of the variation in how “pro-Russian” various European parties are.

Specifically, we merged the preliminary single-wave dataset for waves 22 (GLES 2022), 23 (GLES 2023b), and 24 (GLES 2023c) to the cumulative file containing data for waves 1–21 (GLES 2023a). Our analysis focuses on the “A” samples, containing the bulk of the panelists and available for remote access.

Given social desirability bias, it is possible that the actual number of respondents with a friendly view of Putin is a bit higher, especially in postinvasion waves.

In Fig. C1 of the online appendix, we present analogous findings from a logit model with a stricter definition of pro-Putin views, coding only those with an explicitly positive rating (+1 to +5) as Putin-friendly. The results are similar, although, naturally, the corresponding predicted probabilities (1% and 27%, respectively) are lower, especially in the second scenario.

Because the statistical model treats upward and downward changes symmetrically and identifies the effects of interest from both, this distinction is irrelevant for the statistical model and purely a matter of convenience of the interpretation. When we relax the symmetry assumption and estimate separate models for upward and downward changes in ratings of Putin, we find the effects to be largely symmetrical (see Online Appendix G). In particular, lack of political trust and conspiracy mentality both decrease the tendency for downward adjustments and increase the tendency for upward adjustments. The same holds for alienation from public discourse, but the effect is marginally statistically significant (p = 0.07) only for decreasing downward adjustment.

When we omit the other three facets of political alienation, a larger effect (= 0.67, with p < 0.001) is attributed to alienation from public discourse. If we do the same with lack of support for democracy, its effect remains rather small (= 0.25, with p = 0.084).

References

Aronson, Elliot, and Vernon Cope. 1968. My enemy’s enemy is my friend. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 8(1):8–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021234.

Arzheimer, Kai. 2023. To Russia with love? German populist actors’ positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin. In The impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on right-wing populism in europe, ed. Giles Ivaldi, Emilia Zankina, 156–167. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0010.

Asadzade, Peyman, and Roya Izadi. 2022. The reputational cost of military aggression. Evidence from the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Research and Politics https://doi.org/10.1177/20531680221098337.

Balmas, Meital. 2018. Tell me who is your leader, and I will tell you who you are: Foreign leaders’ perceived personality and public attitudes toward their countries and citizenry. American Journal of Political Science 62(2):499–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12354.

Bertsou, Eri. 2019. Rethinking political distrust. European Political Science Review 11(2):213–230. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000080.

Bordignon, Fabio, Ilvo Diamanti, and Fabio Turato. 2022. Rally ‘round the Ukrainian flag. The Russian attack and the (temporary?) suspension of geopolitical polarization in Italy. Contemporary Italian Politics 14(3):370–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2022.2060171.

Brewer, Paul R. Joseph, Joseph Graf, and Lars Willnat. 2003. Priming or framing: Media influence on attitudes toward foreign countries. International Communication Gazette 65(6):493–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016549203065006005.

Bruder, Marting, Peter Haffke, Nick Neave, Nina Nouripanah, and Roland Imhoff. 2013. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225.

Cartwright, Dorwin, and Frank Harary. 1956. Structural balance: A generalization of Heider’s theory. Psychological Review 63(5):277–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046049.

Dalton, Russel.J. 2004. Democratic challenges, democratic choices: The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Easton, David. 1975. A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science 5(4):435–457.

Festinger, Leon. 1957. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Fisher, Aleksandr. 2021. Trickle down soft power.: Do Russia’s ties to European parties influence public opinion? Foreign Policy Analysis 17(1):106–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/oraa013.

GLES. 2022. GLES Panel 2022, Welle 22. GESIS, Köln. ZA7728 Datenfile Version 1.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13970.

GLES. 2023a. GLES Panel 2016–2021, Wellen 1–21. GESIS, Köln. ZA6838 Datenfile Version 6.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.14114.

GLES. 2023b. GLES Panel 2022, Welle 23. GESIS, Köln. ZA7729 Datenfile Version 1.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.14064.

GLES. 2023c. GLES Panel 2023, Welle 24. GESIS, Köln. ZA7730 Datenfile Version 1.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.14141.

Goldsmith, Benjamin E., Yusaku Horiuchi, and Kelly Matush. 2021. Does public diplomacy sway foreign public opinion? Identifying the effect of high-level visits. American Political Science Review 115(4):1342–1357. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000393.

Golosov, Grigorii. 2020. Useful, but not necessarily idiots. The ideological linkages among the Putin-sympathizer parties in the European parliament. Problems of Post Communism 67(1):53–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2018.1530941.

Graf, Timo. 2022. Zeitenwende im sicherheits- und verteidigungspolitischen Meinungsbild. Potsdam: ZMSBw. https://doi.org/10.48727/opus4-560.

Hahl, Oliver, Kim Minjae, and Ezra W. Zuckerman. 2018. The authentic appeal of the lying demagogue: Proclaiming the deeper truth about political illegitimacy. American Sociological Review 83(1):1–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417749632.

Heider, Fritz. 1958. The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Helmus, Todd C., James V. Marrone, Mark N. Posard, and Danielle Schlang. 2020. Russian propaganda hits its mark. Experimentally testing the impact of Russian propaganda and counter-interventions. Santa Monica: RAND Coporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA704-3.html. Accessed 11 July 2022.

Hjorth, Frederik, and Rebecca Adler-Nissen. 2019. Ideological asymmetry in the reach of pro-Russian digital disinformation to United States audiences. Journal of Communication 69(2):168–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz006.

Hooghe, Marc. 2017. Trust and elections. In The Oxford handbook of social and political trust, ed. Eric M. Uslaner, 617–631. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooghe, Marc, and Ruth Dassonneville. 2018. A spiral of distrust: A panel study on the relation between political distrust and protest voting in Belgium. Government and Opposition 53(1):104–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.18.

Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, Ryan Bakker, Seth Jolly, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Anna Vachudova. 2024. The Russian threat and the consolidation of the West: How populism and EU-skepticism shape party support for Ukraine. European Union Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165241237136.

Huang, Christine. 2020. Views of Russia and Putin remain negative across 14 Nations. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/12/16/views-of-russia-and-putin-remain-negative-across-14-nations/. Accessed 4 Aug 2023.

Hurwitz, Jon, and Mark Peffley. 1987. How are foreign policy attitudes structured? A hierarchical model. American Political Science Review 81(4):1099–1120. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962580.

Imhoff, Ronald, and Martin Bruder. 2014. Speaking (un-)truth to power: Conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. European Journal of Personality 28(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1930.

Imhoff, Roland, Tisa Bertlich, and Marius Frenken. 2022. Tearing apart the “evil” twins: A general conspiracy mentality is not the same as specific conspiracy beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology 46:101349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101349.

Ingenhoff, Diana, and Susanne Klein. 2018. A political leader’s image in public diplomacy and nation branding: The impact of competence, charisma, integrity, and gender. International Journal of Communication 12:4507–4532.

Johnston Conover, Pamela, Karen A. Mingst, and Lee Sigelman. 1980. Mirror images in Americans’ perceptions of nations and leaders during the Iranian hostage crisis. Journal of Peace Research 17(4):325–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234338001700404.

Kinne, Brandon J., and Zeev Maoz. 2023. Local politics, global consequences: How structural imbalance in domestic political networks affects international relations. Journal of Politics 85(1):107–124. https://doi.org/10.1086/720311.

Lamberty, Pia, Maheba Goedeke Tort, and Corinne Heuer. 2022b. Von der Krise zum Krieg: Verschwörungserzählungen über den Angriffskrieg gegen die Ukraine in der Gesellschaft. CeMAS Insitut. https://cemas.io/publikationen/von-der-krise-zum-krieg-verschwoerungserzaehlungen-ueber-den-angriffskrieg-gegen-die-ukraine-in-der-gesellschaft/2022_05_CeMAS_ResearchPaper_Verschwoerungserzaehlungen_Ukraine.pdf. Accessed 4 Aug 2023.

Lamberty, Pia, Corinne Heuer, and Josef Holnburger. 2022a. Belastungsprobe für die Demokratie: Pro-russische Verschwörungserzählungen und Glaube an Desinformation in der Gesellschaft. CeMAS Insitut. https://cemas.io/publikationen/belastungsprobe-fuer-die-demokratie/2022-11-02_ResearchPaperUkraineKrieg.pdf. Accessed 4 Aug 2023.

Letterman, Clark. 2018. Image of Putin, Russia suffers internationally. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/12/06/image-of-putin-russia-suffers-internationally/. Accessed 28 June 2022.

Mader, Matthias. 2015. Grundhaltungen zur Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik in Deutschland. In Sicherheitspolitik und Streitkräfte im Urteil der Bürger, ed. Heiko Biehl, Harald Schoen, 69–96. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Mader, Matthias, and Harald Schoen. 2023. No Zeitenwende (yet): Early assessment of German public opinion toward foreign and defense policy after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 64:525–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-023-00463-5.

Mader, Matthias, Nikolay Marinov, and Harald Schoen. 2022. Foreign anti-mainstream propaganda and democratic publics. Comparative Political Studies 55(10):1732–1764. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211060277.

Marien, Sofie. 2017. The measurement equivalence of political trust. In Handbook on political trust, ed. Sonja Zmerli, Tom W.G. van der Meer, 89–103. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Michael, George. 2019. Useful idiots or fellow travelers? The relationship between the American far right and Russia. Terrorism and Political Violence 31(1):64–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1555996.

Nincic, Miroslav, and Bruce Russett. 1979. The effect of similarity and interest on attitudes toward foreign countries. Public Opinion Quarterly 43(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1086/268492.

Norris, Pippa. 1999. Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, Pippa. 2017. The conceptual framework of political support. In Handbook on political trust, ed. Sonja Zmerli, Tom W.G. van der Meer, 19–32. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural backlash. Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

N‑tv. 2022. Prorussische Demos in mehreren deutschen Städten. https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Pro-russische-Demos-in-Deutschland-Hunderte-Menschen-protestieren-gegen-Russismus-article23259869.html. Accessed 4 Aug 2023.

Olsen, Jonathan. 2018. The Left Party and the AfD. German Politics & Society 36(1):70–83. https://doi.org/10.3167/gps.2018.360104.

Onderco, Michael. 2019. Partisan views of Russia: Analyzing European party electoral manifestos since 1991. Contemporary Security Policy 40(4):526–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1661607.

Onderco, Michael. 2020. European crises and foreign policy attitudes in Europe. In Towards a segmented European political order: the European Union’s post-crises conundrum, ed. Jozef Bataro, John E. Fossum, 225–242. London: Routledge.

Pfaff, Jan. 2022. Die Nato-war-schuld-Linken. taz am Wochenende. https://taz.de/Linke-und.derUkrainekrieg/!5834130/. Accessed 3 Aug 2023.

Pomerantsev, Peter. 2016. The Kremlin’s information war. In Authoritarianism goes global. The challenge to democracy, ed. Larry Diamond, Marc F. Plattner, and Christopher Walker, 174–186. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Poushter, Jacob, and Aidan Connaughton. 2022. Zelenskyy inspires widespread confidence from U.S. public as views of Putin hit new low. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/03/30/zelenskyy-inspires-widespread-confidence-from-u-s-public-as-views-of-putin-hit-new-low/. Accessed 22 Aug 2023.

Radnitz, Scott. 2022. Solidarity through cynicism? The influence of Russian conspiracy narratives abroad. International Studies Quarterly https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqac012.

Rathje, Jan, Miro Dittrich, and Martin Müller. 2022. Verschwörungsideologische Positionierung zum Ukraine Krieg und die Rolle von RT DE auf Telegram. CeMAS Institut. https://cemas.io/publikationen/russische-desinformation/2022-04-01_ResearchPaperRussischeDesinformation.pdf. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Schmidt, Martin. 2022. Ukraine-Krieg. Wie hält es die AfD mit Russland? tagesschau.de. https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/innenpolitik/afd-russland-115.html. Accessed 9 June 2022.

Schmitz, David. 2023. „Feiern den Krieg“. Entsetzen über pro-russische Demos in Deutschland. Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger. https://www.ksta.de/politik/ukraine-krieg/pro-russische-demos-frankfurt-koeln-entsetzen-kritik-krieg-ukraine-russland-tag-der-befreiung-567064. Accessed 3 Aug 2023.

Silver, Laura, and J.J. Moncus. 2021. Few across 17 advanced economies have confidence in Putin. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/06/14/few-across-17-advanced-economies-have-confidence-in-putin/. Accessed 9 June 2022.

Smirnova, Julia, and Hannah Winter. 2021. Ein Virus des Misstrauens. Der russische Staatssender RT DE und die deutsche Corona-Leugner-Szene. Institute for Strategic Dialogue. https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/ein-virus-des-misstrauens-der-russische-staatssender-rt-de-und-die-deutsche-corona-leugner-szene1/. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Smirnova, Julia, Annelie Ahonen, Nora Mathelemuse, Helena Schwertheim, and Hannah Winter. 2022. Bundestagswahl 2021. Digitale Bedrohungen und ihre Folgen. Institute for Strategic Dialogue. https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/bundestagswahl-2021-digitale-bedrohungen-und-ihre-folgen/. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Snegovaya, Maria. 2022. Fellow travelers or Trojan horses? Similarities across pro-Russian parties’ electorates in Europe. Party Politics 28(3):409–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068821995813.

Snegovaya, Maria, and Kohai Watanabe. 2021. The Kremlin’s social media influence inside the United States: A moving target. Free Russia Foundation. https://www.4freerussia.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2021/02/The-Kremlins-Social-Media-Influence-Inside-the-United-States-A-Moving-Target-1.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2022.

Soares, Felipe B., Anatoliy Gruzd, and Philip Mai. 2023. Falling for Russian propaganda: Understanding the factors that contribute to belief in pro-Kremlin disinformation on social media. Social Media + Society https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231220330.

Tims, Albert R., and M. Mark Miller. 1986. Determinants of attitudes toward foreign countries. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 10(4):471–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(86)90046-5.

Uscinski, Joseph E., Adam E. Enders, Michelle I. Seelig, Casey A. Klofstad, John R. Funchion, Caleb Everett, Stefan Wuchty, Kamal Premaratne, and Manohar N. Murthi. 2021. American politics in two dimensions: Partisan and ideological identities versus anti-establishment orientations. American Journal of Political Science 65(4):877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12616.

Wike, Richard, Janell Fetterolf, Moira Fagan, and Sneha Gubbala. 2022. International attitudes toward the U.S., NATO and Russia in a time of crisis. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2022/06/22/international-attitudes-toward-the-u-s-nato-and-russia-in-a-time-of-crisis/. Accessed 3 Aug 2023.

Wondreys, Jakub. 2023. Putin’s puppets in the West? The far right’s reaction to the 2022 Russian (re)invasion of Ukraine. Party Politics https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688231210502.

Wood, Steve. 2021. “Understanding” for Russia in Germany: international triangle meets domestic politics. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 34(6):771–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1703647.

Acknowledgements

Parts of this article build on Hoffeller’s master’s thesis written under Steiner’s supervision, available at https://doi.org/10.25358/openscience-8518. We thank Sven Hillen, Matthias Mader, and Armin Schäfer, participants of the Colloquium on Comparative Politics at JGU Mainz, as well as our two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

L. Hoffeller and N.D. Steiner declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffeller, L., Steiner, N.D. Sympathies for Putin Within the German Public: A Consequence of Political Alienation?. Polit Vierteljahresschr (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-024-00541-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-024-00541-2