Abstract

Background

Health literacy is often viewed as a static trait in longitudinal studies, which may over or underestimate an individual’s ability to manage one’s health.

Objectives

We sought to examine health literacy over time among older adults using three widely used measures.

Design

A prospective cohort study.

Participants

Community-dwelling adults ages 55 to 74 at baseline with at least one follow-up visit (N = 656) recruited from one academic internal medicine clinic and six community health centers in Chicago, IL.

Measures

Health literacy was measured using the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), Newest Vital Sign (NVS), and Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) at baseline and up to three follow-up time points.

Results

In unadjusted analyses, significant changes since baseline were found beginning at the second follow-up (mean (M) = 6.0 years, SD = 0.6) for the TOFHLA (M = − 0.9, SD = 0.95, p = 0.049) and the REALM (M = 0.3, SD = 2.5, p = 0.004) and at the last follow-up (M = 8.6 years, SD = 0.5) for the NVS (M = − 0.2, SD = 1.4, p = 0.02). There were non-linear effects of baseline age on TOFHLA and NVS scores over time (piecewise cubic spline p = 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) and no effect on REALM scores (B = 0.02, 95% CI − 0.01 to 0.04, p = 0.17) using multivariable mixed-effects linear regression models, controlling for race, education, income, and comorbidity.

Conclusion

We found a negative relationship between age and health literacy over time as measured by the TOFHLA and NVS. Health literacy barriers appear to be more prevalent among individuals in later life, when self-care demands are similarly increasing. Clinicians might consider strategies to assess and respond to limited health literacy, particularly among patients 70 and older. REALM performance remained stable over 10 years of follow-up. This questions whether health literacy tools measure the same attribute. Prospective health literacy studies should carefully consider what measures to use, depending on their objective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Health literacy is most commonly defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions”.1 More than three decades of research have established limited health literacy as a risk factor for poorer health.2, 3 Interestingly, nearly all prospective health literacy investigations to date have treated health literacy as a static individual trait, using baseline measures to predict future health outcomes. However, it is plausible that with older age when many cognitive processes decline on average, health literacy skills may also degrade in a similar trajectory.

Multiple studies have established relationships between health literacy and cognitive function.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 In addition, research has found that cognitive abilities explain a large proportion (35 to 77%) of the relationship between health literacy and health behaviors and outcomes.5, 6, 13 Collectively, this suggests that health literacy assessments may reflect a range of cognitive abilities.

Fluid cognitive abilities or those that are necessary to problem solve and learn new skills are known to decline with age, while crystallized abilities or those that reflect aspects of general knowledge and vocabulary amassed over one’s lifespan remain stable or increase.14 Considering three of the most widely used health literacy assessments, the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA)15 and the Newest Vital Sign (NVS)16 measure reading comprehension, reasoning, and numeracy are highly correlated with more “fluid” cognitive abilities; whereas the Rapid Estimate of Adult Learning in Medicine (REALM)17 assesses correct pronunciation of medical terms and is more closely aligned with “crystallized” abilities.8, 9, 13, 18 Cross-sectional studies have observed an inverse relationship between age and health literacy when measured by assessments more closely linked to fluid abilities.18,19,20,21 This might suggest that decline likely occurs in these measures over time. Weaker associations, if any, exist with crystallized measures (i.e., REALM).18, 20, 22, 23 Therefore, depending on how health literacy is measured, an individual’s skills and capacity to access, understand, and use health information may deteriorate with time. Failure to adequately address a decline in these skills may be particularly detrimental among older adults who naturally experience poorer cognitive and physical health with aging.

Few observational studies have prospectively examined performance on health literacy measures over time, and these studies are limited by design, with homogeneous samples and the use of only one assessment.7, 24, 25 It is unclear whether the relationships between health literacy assessments and fluid or crystallized cognitive abilities found in cross-sectional studies persist over time. No studies to our knowledge have prospectively examined the trajectories of multiple health literacy measures.

The objective of this study was to examine the overall and age-specific change in health literacy over 10 years of follow-up on three of the most widely used measures among a diverse cohort of aging adults. We hypothesized health literacy assessments known to be more closely associated with fluid cognitive abilities (TOFHLA, NVS) would decline with older age, while a more knowledge-based measure (REALM) would remain stable.

METHODS

Study Population and Procedure

The Health Literacy and Cognitive Function among Older Adults study (“LitCog”) is a prospective cohort study consisting of 900 participants enrolled from one academic general internal medicine clinic and six community health centers beginning in 2008. More details are reported elsewhere.6, 12 Briefly, English-speaking patients ages 55 to 74 years who sought regular care from study sites (defined as 2 visits within 2 years) and had adequate cognitive capacity, based on the 6-item screener,26 were eligible. Research coordinators, trained and certified according to a manual of operations, administered structured in-person interviews with enrolled participants at baseline and every 2–5 years thereafter. Our a priori protocol was to contact participants after 2.5 years, but the window was extended to maximize retention. Of the 900 enrolled, 656 (73%) completed at least one follow-up interview at the time of this investigation and were included in these analyses. Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study (STU00026255) and patients provided written informed consent prior to participation at each time point.

Health Literacy Assessments

Health literacy was assessed using the three most commonly used measures: the full version of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM).15,16,17

The TOFHLA uses actual materials that patients might encounter in healthcare to test their reading fluency and numeracy and takes approximately 20 min to complete. The 50-item reading comprehension section uses the cloze procedure where words in a passage are omitted and four multiple-choice items are provided. For the 17-item numeracy assessment, participants answer questions such as “If you take your first tablet at 7:00 am, when should you take the next one?” after being shown a prescription label. Total scores are weighted for possible scores ranging 0–100 and can be interpreted as inadequate (0–59), marginal (60–74), or adequate (75–100) health literacy.15

The NVS is a screening tool used to determine risk for limited health literacy. Patients are provided a nutrition label from a pint of ice cream and asked six questions about how they would interpret and act on the information, including “If you eat the entire container, how many calories will you eat?.” Scores are classified as high likelihood (0–1) or possibility2, 3 of limited health literacy, and adequate health literacy4,5,6.16

The REALM is a word-recognition test where patients are asked to read aloud as many words as they can from a list of 66 health-related terms arranged in order of increasing difficulty, beginning with fat and ending with impetigo. Scores are based on the total number of words pronounced correctly, with dictionary pronunciation being the scoring standard and interpreted as low (0–44), marginal (45–60), or adequate (61–66) literacy.17

Covariates

For descriptive analyses, baseline age (55–74) was categorized into 5-year increments (i.e., 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74). The latter 2 groups were ultimately combined to create three groups, with approximately one-third of participants in each. Race (Black, White, other), education (high school or less, some college or technical school, college graduate, graduate degree), and annual household income (< $15,000, $15,000–29,999, $30,000–49,999, ≥ $50,000, missing) were captured via self-report at baseline, and a number of chronic conditions (diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary vascular disease, coronary heart failure, asthma, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, stroke, arthritis, cancer, depression) were reported at each time point.

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were compared across the three age groups using chi-square tests for categorical characteristics and one-way ANOVA tests for continuous characteristics. Change in performance on each health literacy measure between baseline and each follow-up interview was compared using paired t tests overall and within age groups. Change scores were then compared between age categories using one-way ANOVA. We examined the decline in health literacy category for each measure to determine if changes were clinically meaningful. We compared the proportions of participants with adequate literacy at baseline that declined to marginal or low categories by age groups using chi-square tests.

Multivariable mixed-effects linear regression models with random intercepts were fit with each health literacy measure as the outcome, and including age in years as the main variable of interest, adjusting for a priori selected sociodemographic variables including race, education, and income, along with the number of chronic conditions at each time point. Markov chain Monte Carlo methods were used to impute missing values of health literacy scores.27 Initial parameter estimates were set using expectation-maximization (EM) estimates, and multiple chains were used to create five complete datasets. Parameter estimates from generalized linear mixed models conducted on each of these datasets were combined using PROC MIANALYZE in SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

To test for evidence that the change in health literacy may not be linear over time, a spline effect of age was fit for each outcome using a piecewise cubic spline effect in PROC GLIMMIX with knots placed at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles.28 In the event that the additional parameter required for the spline was not significant (i.e., no evidence to suggest a non-linear relationship), a linear model was fit instead. Plots were created using only the first imputed data set, as the multiple data sets showed similar trends. All analyses were completed using SAS software version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Role of the Funding Source

This research was supported by the National Institute of Aging (R01AG030611) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HL116630). The funders had no role in the design, conduct, study analysis, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

RESULTS

Study Sample

Characteristics of the cohort (n = 656) are described in Table 1, both as an overall sample and by age category. On average, participants were 63 years old (SD = 5.4; range 55–74 years) at baseline with 31.4% being 55–59, 30.8% 60–64, and 37.8% 65–74 years old. The majority of the sample were female (70.3%) and self-reported either Black (44.2%) or non-Hispanic White race (49.2%). Participants were socially and economically diverse by years of schooling (26.1% completing high school or less), and household income (34.6% earned less than $25,000 a year). Individuals on average had 2.6 chronic conditions (SD = 1.8). Participant characteristics did not generally differ by age category; the exception being income, with the youngest age group reporting more extremes of household income (with 17.1% reporting less than $10,000 per year, and 55.3% reporting more than $50,000, compared to overall sample estimates of 12.4% and 49.8%, respectively, p = 0.003).

Unadjusted Change in Health Literacy Performance

Average scores for all three health literacy measures did not differ by age group at baseline (Table 2). From baseline to the first follow-up (mean (M) time = 3.2 years, SD = 0.5), there were no significant changes in health literacy, except with TOFHLA scores among LitCog participants ages 65–74 at baseline (M = − 1.4, SD = 8.2, p = 0.01). From baseline to the second follow-up (M time = 6.0 years, SD = 0.6), there was a significant change in health literacy as measured by the TOFHLA (M = − 0.9, SD = 9.5, p = 0.049) and REALM (M = 0.3, SD = 2.5, p = 0.004), but not the NVS (M = − 0.1, SD = 1.6, p = 0.32). Finally, from baseline to the last follow-up (M time = 8.6 years, SD = 0.5), a significant decline occurred in TOFHLA scores, overall (M = − 1.8, SD = 8.7, p < 0.001) and within all age groups (Table 2). NVS scores declined as well (M = − 0.2, SD = 1.4, p = 0.02), particularly in those 65 and older at baseline (M = − 0.4, SD = 1.6, p = 0.005).

Multivariable Analysis of Age on Health Literacy Performance over Time

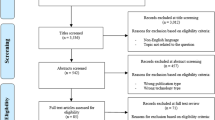

Results of the multivariable mixed linear models controlling for race, education, income, and number of chronic conditions are displayed in Figure 1. The spline effect for age is shown for all measures. This was significant for TOFHLA (p = 0.01), suggesting a non-linear effect of age on health literacy over time, with gradual decline beginning around age 60 and becoming more prominent after age 75. Similarly, there was a non-linear effect for the NVS (p < 0.001), with decline not occurring until age 65 and more rapid decline after age 75. There was no evidence of non-linearity for the REALM (p = 0.10); therefore, the linear effect was also shown (B = 0.02, 95% CI − 0.01 to − 0.04, p = 0.17).

Associations between age and health literacy over time for each measure (TOFHLA, Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (range 0–100); NVS, Newest Vital Sign (range 0–6); REALM, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (range 0–66)). Solid curves depict mean scaled health literacy scores modeled using piecewise cubic splines (with knots at 10th percentiles, 50th percentiles, and 90th percentiles of age distributions). The dashed line depicts the linear regression curve for the REALM as there was no evidence to indicate the model was non-linear. All models were adjusted for race, income, and the total number of chronic conditions.

Decline in Health Literacy Category

In those with adequate literacy based on the TOFHLA at baseline and complete follow-up data (n = 427 at first, n = 350 at second, n = 289 at last follow-up), 8.4%, 11.1%, and 11.1% declined to either marginal or low categories at the respective time points (Table 3). While higher proportions declined in those 65–74, these category changes were not significant by age. Declines in NVS categories were 22.3%, 20.4%, and 23.4%, respectively, with significant gradient decline by age at all three time points. Very few declined REALM categories from baseline to follow-up (range 1.6–3.0%), with no differences by age.

DISCUSSION

In this community-based cohort of older adults, we observed differential change in health literacy skills over time across three commonly used assessments. We first observed overall changes in our cohort from baseline to second follow-up (mean 6 years) in health literacy assessed by the TOFHLA and REALM, but not the NVS, although the NVS exhibited significant changes with longer follow-up (mean 8.6 years). These changes occurred more prominently in older participants. When accounting for aging in multilevel models, and for attrition using multiple imputation methods, both the NVS and TOFHLA demonstrated non-linear declines, while performance on the REALM remained unchanged. This supports our hypotheses, as trajectories for the TOFHLA and NVS mimicked fluid cognitive abilities and REALM trajectories remained stable over time, similar to crystallized abilities. These results align with a review of cross-sectional studies that found associations between age and health literacy varied depending on the measure.18 Deficits in older individuals were found in 80% of the studies using the TOFHLA, S-TOFHLA, or the NVS to measure health literacy, whereas only 23% of studies using the REALM found age-related associations. Our study is the first to show this pattern also holds in longitudinal versus cross-sectional analyses.

Our findings highlight how these three longstanding health literacy assessments capture different aspects of the multifaceted, underlying construct. With the REALM often considered a proxy for acquired health knowledge, it makes sense that despite age-related declines in cognitive function, one is still able to maintain knowledge over time. Yet, noted declines in health literacy, as measured by the TOFHLA and NVS, suggest potential challenges patients may face to accurately perform common healthcare tasks. Interestingly, our findings suggest skills measured by the TOFHLA (i.e., reading comprehension, reasoning, and numeracy) remain only slightly affected in early older age, with gradual decline beginning around age 60 and steeper decline into the seventies. The NVS, which primarily measures numeracy, remains stable until around 65, with steeper decline until 80 and steeper decline thereafter. This may be particularly salient to clinicians, as patients’ abilities to process new information may decline at a time when self-care demands are increasing. Periodically confirming patients are able to understand and apply new information may be necessary, particularly when numeracy skills are needed.

These results further emphasize the implications of choosing the optimal health literacy measure for research, depending on the purpose and design of the study. In general, health literacy appears to remain stable until adults reach their sixties. Declines in certain health literacy skills in older adults would likely be masked if a study were to only use the REALM. However, if the purpose is to examine or control for literacy, premorbid function, or general health knowledge, the REALM may be sufficient. The NVS continues to grow in popularity due to its short administration time, availability in Spanish, and lack of ceiling effects often found with the TOFHLA and the REALM.29 It appears performance on the NVS does decline over longer follow-up, but its abbreviated score (0–6) may lack the precision to detect decline across only two time points less than a decade apart. Therefore, it may not be as useful in longitudinal studies examining changes in health literacy pre- and post-intervention.

Similar to our study, research performed to date found a significant longitudinal decline in health literacy assessments reflecting fluid abilities.7, 24, 25 Morris et al. found S-TOFHLA scores to decline over 2 years in older patients with diabetes, particularly in those 65 or older at baseline, who declined 1.1 points on average.24 We found comparable results in our sample using the full TOFHLA, with those 65 and older decreasing 1.4 points on average over a 3-year period and closer to 2 points with longer follow-up.

Kobayashi et al. similarly found a change in health literacy between 2 time points in older adults over a period of 6 years, with 20% declining at least 1 point using a 4-item measure.7 The first to examine a change in health literacy over more than 2 time points included yearly assessments over 6 years using the health literacy component of a general literacy measure, although this measure has not been validated to our knowledge.25 Both studies found strong relationships between health literacy decline and cognition, with the former finding associations with decline in memory and executive function, while the latter determined decline in health literacy predicted incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment.7, 25

The LitCog study includes an extensive cognitive battery performed at each time point including measures from 5 domains13; future research will investigate additional cognitive abilities not measured in these studies while also examining potential non-linear trajectories of cognition. Our results also build on this research by extending to multiple health literacy measures in a more diverse cohort, enabling us to compare differential decline by measure. Examining more than two time points allowed us to conduct more robust analyses looking at both differences by age and non-linear longitudinal decline.

Our study has limitations. Although the LitCog cohort is socially and economically diverse, the generalizability may be limited to an English-speaking, predominantly female sample from one urban location. While we found health literacy scores changed significantly over time, the extent of decline may not be clinically meaningful. It is unclear what amount of change could have an effect on self-care behaviors, thereby leading to worse health outcomes. However, a fifth of our sample went from adequate to limited health literacy as measured by the NVS over a 3-year period; health outcomes including functional health status and mortality risk have been shown to differ by these established cutoffs.30, 31 In addition, the LitCog sample may be too young to observe major decline, supported by the observed decline being most prominent in the older age groups. However, with additional assessments being collected for longer follow-up (through 2025), we anticipate more significant decline and may be able to determine what amount of change will have detrimental effects on the health of older adults.

In summary, viewing health literacy as a static trait among older adults may be problematic, both clinically and in research settings. Skills needed to actively learn and apply new information may decline with older age and providers may need to routinely assess patients’ capacity to self-manage health. Health literacy and aging studies should carefully consider the appropriate health literacy measure for study, depending on the purpose.

References

Institute of Medicine. (2004). In L. Nielsen-Bohlman, A. Panzer, & D. A. Kindig (Eds.), Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97-107.

DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228-39.

Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA. Health literacy, cognitive abilities, and mortality among elderly persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):723-6. Epub 2008/03/12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0566-4. PubMed PMID: 18330654; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2517873.

O’Conor R, Wolf MS, Smith SG, et al. Health literacy, cognitive function, proper use, and adherence to inhaled asthma controller medications among older adults with asthma. Chest. 2015;147(5):1307-15. Epub 2014/10/03. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-0914. PubMed PMID: 25275432; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4420182.

Serper M, Patzer RE, Curtis LM, et al. Health literacy, cognitive ability, and functional health status among older adults. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(4):1249-67. Epub 2014/01/31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12154. PubMed PMID: 24476068; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4111764.

Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, von Wagner C. Cognitive Function and Health Literacy Decline in a Cohort of Aging English Adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):958-64. Epub 2015/02/15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3206-9. PubMed PMID: 25680352; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4471026.

Kobayashi LC, Smith SG, O’Conor R, et al. The role of cognitive function in the relationship between age and health literacy: a cross-sectional analysis of older adults in Chicago, USA. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e007222. Epub 2015/04/25. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007222. PubMed PMID: 25908675; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4410118.

Ownby RL, Acevedo A, Waldrop-Valverde D, Jacobs RJ, Caballero J. Abilities, skills and knowledge in measures of health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(2):211-7. Epub 2014/03/19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.02.002. PubMed PMID: 24637163; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4040019.

Levinthal BR, Morrow DG, Tu W, Wu J, Murray MD. Cognition and health literacy in patients with hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1172-6.

Federman AD, Sano M, Wolf MS, Siu AL, Halm EA. Health literacy and cognitive performance in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1475-80. Epub 2009/06/12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02347.x. PubMed PMID: 19515101; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2754116.

Yost KJ, DeWalt DA, Lindquist LA, Hahn EA. The association between health literacy and indicators of cognitive impairment in a diverse sample of primary care patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):319-26. Epub 2013/08/13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.006. PubMed PMID: 23932515; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3802526.

Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Wilson EA, et al. Literacy, Cognitive Function, and Health: Results of the LitCog Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1300-7. Epub 2012/05/09. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2079-4. PubMed PMID: 22566171; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3445686.

Horn JL. The Theory of Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence in Relation to Concepts of Cognitive Psychology and Aging in Adulthood. In: Craik FIMT, S., editor. Aging and Cognitive Processes Advances in the Study of Communication and Affect. 8. Boston, MA: Springer; 1982.

Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):537-41. Epub 1995/10/01.

Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the Newest Vital Sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:514-22.

Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):433-5. PubMed PMID: MEDLINE:1936717.

Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, von Wagner C. Aging and Functional Health Literacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71(3):445-57. Epub 2014/12/17. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu161. PubMed PMID: 25504637; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4834761.

Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Sudano J, Patterson M. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(6):S368-74.

Barber MN, Staples M, Osborne RH, Clerehan R, Elder C, Buchbinder R. Up to a quarter of the Australian population may have suboptimal health literacy depending upon the measurement tool: results from a population-based survey. Health Promot Int. 2009;24(3):252-61.

Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):267-75.

Gordon MM, Hampson R, Capell HA, Madhok R. Illiteracy in rheumatoid arthritis patients as determined by the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) score. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(7):750-4. Epub 2002/07/04.

Sudore RL, Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, et al. Limited literacy in older people and disparities in health and healthcare access. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):770-6. Epub 2006/05/16. JGS691 [pii] https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00691.x.

Morris NS, Maclean CD, Littenberg B. Change in health literacy over 2 years in older adults with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39(5):638-46. Epub 2013/08/22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721713496871.

Yu L, Wilson RS, Han SD, Leurgans S, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Decline in Literacy and Incident AD Dementia Among Community-Dwelling Older Persons. J Aging Health. 2018;30(9):1389-405. Epub 2017/06/25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317716361. PubMed PMID: 28645223; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5869171.

Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item Screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002; 40: 771–81.

Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997.

Harrell FE, Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2015.

Mancuso JM. Assessment and measurement of health literacy: an integrative review of the literature. Nurs Health Sci. 2009;11(1):77-89. Epub 2009/03/21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00408.x.

Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA, Gazmararian JA, Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1503-9. Epub 2007/07/25. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503.

Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson J, Baker DW. In search of ‘low health literacy’: threshold vs. gradient effect of literacy on health status and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(9):1335-41. Epub 2010/02/20. S0277-9536(10)00034-1 [pii] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.013.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AG030611) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HL116630).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Wolf reports grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Sanofi, grants from Merck, grants from Eli Lilly, grants from Amgen, personal fees from Luto UK, personal fees from MedLearning Group, and grants from Gordon And Betty Moore Foundation, outside the submitted work. No other authors reported conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curtis, L.M., Kwasny, M.J., Opsasnick, L. et al. Change in Health Literacy over a Decade in a Prospective Cohort of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 916–922 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06423-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06423-8