Abstract

Background

There is great interest in identifying factors that are related to positive patient experiences such as physician communication style. Documented gender-specific physician communication and patient behavior differences raise the question of whether gender concordant relationships (i.e., both the provider and patient share the same gender) might affect patient experiences.

Objective

Assess whether patient experiences are more positive in gender concordant primary care relationships.

Design

Statewide telephone surveys. Linear mixed regression models to estimate the association of CAHPS scores with patient gender and gender concordance.

Subjects

Two probability samples of primary care Medicaid patients in Connecticut in 2017 (5/17–7/17) and 2019 (7/19–10/19).

Main Measures

Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey augmented with questions about aspects of care most salient to PCMH-designated organizations and two questions to assess access to mental health services.

Key Results

There were no significant effects of gender concordance and differences in experiences by patient gender were modest.

Conclusions

This study did not support the suggestion that patient and physician gender and gender concordance have an important effect on patient experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asking patients about their care experiences is a widely used approach to assess “patient-centered care.” 1,2,3 Positive care experiences have been linked to better follow-up,4 adhering to care recommendations,5,6,7 and health outcomes.8,9,10

There is great interest in identifying factors that are related to positive patient experiences such as physician communication style.11,12 Research indicates that clinician communication styles differ by physician gender.13 Female physicians tend to exhibit more encouragement,14 empathy,15 and more patient centric behaviors in their conversations with patients.13,14

Similarly, patient behaviors and preferences can vary by gender. Female patients, for example, receive fewer physical exams, but utilize more diagnostic services and make more primary care visits than male patients.16 Female communication styles generally are related to more positive patient experiences, but the evidence is mixed on whether physician gender is systematically related to more positive patient experiences.14,17,18

Documented gender-specific physician communication17,18,19 and patient behavior differences20 raise the question of whether gender concordant relationships (i.e., both the provider and patient have the same gender) might affect patient–physician communication and other aspects of care. Some social scientists endorse social dominance theory, which posits that men generally have higher status in our social hierarchy and tend to show higher levels of social dominance orientation than women.21 Furthermore, physicians tend to have high status and power and being humane and caring has been shown to be more associated with being a female than a male physician.22 If this is correct, one might expect females to feel reluctant to be fully forthcoming with male physicians and/or think that their male physicians are less empathetic and trustworthy23 than female physicians. Others, however, have posited that men and women are more similar than different and that there may be no systematic gender differences in social dominance. 24

Empirical studies exploring the effect of concordant patient–provider relationships have yielded mixed results. A study of former emergency room patients found that the satisfaction of male patients was unrelated to concordance, but female patients in concordant provider relationships gave more positive feedback with respect to trust, concern, and time spent with the patient, compared to female patients with male clinicians. 25 Another study of emergency department patients, however, found that female patients treated by female physicians were more likely to report better experiences with their physician.26 A study of heart attack patients found higher mortality when male physicians treat female patients but men and women had similar outcomes when treated by female physicians.27

Other studies have shown that male concordant relationships tend to be associated with less patient engagement during the medical encounter,28 that female concordant relationships are related to better patient-centered care in clinic visits29 and higher cancer screening results. 30and that the risk of reporting problems with physician respect was lowest when female patients were seen by female providers.31

Some studies have found no effects or negative results. A study of treatment by hospitalists found that patient experience scores were not related to concordance. 32 Another study found that concordance was not related to the receipt of advice for weight-related issues.19 A study of outpatient gynecological care found worse patient experience scores for gender concordant pairs and that women physicians got lower patient experience scores.33

One study found that in doctor–patient relationships where there is a language barrier, gender discordance made communication more difficult.34 But in discussions concerning emotional and psychosocial problems, gender discordance appeared to afford better communication.35 It has also been suggested that a male clinician–female patient relationship may make the provider both less confident regarding the medical problem and more likely to diminish the perceived seriousness of the condition.36 Though inconclusive, these findings underscore potential important associations between gender concordance and the nature of physician–patient interactions.

Such relationships have been analyzed in inpatient27,32 and specialty care settings, including emergency departments, 25,26 and obstetrics and gynecology.37,38 However, the Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) reports that primary care is the most frequented medical care.39 Given the importance of patient-centered communication in primary care and the interest in how gender affects such communication, this study analyzed data collected using a Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey 3as part of a state wide study of primary care. The goal was to contribute to the research on gender concordant relationships in the primary care setting,16,20,29 in the belief that findings could help optimize communication and positive patient experiences in primary care.

Methods

Design

As part of another repeated cross-sectional study of improvement in primary care practices in Connecticut, we surveyed probability samples of primary care Medicaid patients in CT at three different times during the study period (2017–2019). A sample of Medicaid patients was drawn from each primary care organization in the state and a separate group of patients who were treated by a physician unaffiliated with a primary care organization. Approximately equal numbers of patients (unless constrained by total number of patients) were selected from each primary care network.

Three waves of surveys were conducted by telephone (I; 5/2/17–7/17/17; II: 7/27/17–10/2/18; III: 7/8/19–10/21/19). There was a large amount of missing data for provider gender in the second wave, so all analyses presented herein are based on the first and third waves of surveys. The missing data was due to a change in the way data was coded and stored and not the quality of care experiences.

We used the Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey, which asks about care in the previous 6 months, augmented with questions about aspects of care most salient to PCMH-designated organizations.40 Two questions were added to assess access to mental health services (Table 1). Survey responses were summarized in 10 measures by calculating the average response to completed items in the same domain (Table 1). We also calculated a grand average of those 10 measures. All measures were scaled to a 0–100 score to simplify interpretation, with higher scores indicating better patient experience.

Analysis

We analyzed these cross-sectional observational data to address the study questions. We estimated descriptive statistics using weights that accounted for differential sampling across primary care networks. We also estimated linear mixed regression models using unweighted data in which the CAHPS score was the dependent variable and independent variables were patient gender (female vs. male) and gender concordance (patient and provider have same gender: yes vs. no). All models were adjusted41 for the following variables (all categorical): age, overall health, education, race/ethnicity, and primary care network-wave (e.g., network A-wave I, network A-wave III). In an initial set of models, we included an interaction between patient gender and concordance to see if the effect of concordance varies by gender. This interaction was not significant for any of the models, so we present the results of models with only main effects. The mixed models included random effects for provider to account for correlation among patients with the same provider. We used unweighted data in the regression models because there was no reason to think that the estimated coefficients would vary across practices or waves. Thus, the unweighted analyses should yield unbiased coefficient estimates. Furthermore, using weights in regression models can sometimes result in higher standard errors.42,43,44 The Yale Human Investigations Committee determined that the study (Protocol MODCR00003391) was exempt.

Results

After removing non-working, fax, and business numbers and persons who were no longer in the Medicaid program, the number of surveys attempted and completed and response rates were as follows: Wave I: 97,862; 6505; 6.6%; Wave III: 166,359; 5875; 3.5%. The information provided changed during the study, so we only have information about the characteristics of non-respondents for Wave I. In that survey, women were more likely to respond than men (6.8% vs. 6.4%) and non-Hispanic Blacks were more likely to respond than Hispanic and non-Hispanic White patients (8.4% vs. 5.8% vs. 6.6%). Of the study sample (N = 12380), 64% were females, 26% were between 45–54, 44% were non-Hispanic white, 45% had a high school diploma or GED as their highest level of education, 38% reported being in good overall health, and 56% had a female provider (Table 2). The respondents consisted of 2045 male patients with male doctors and 4875 female patients with female doctors (referred to as concordant relationships). As for discordant relationships, 2703 female patients had a male provider and 2206 male patients had a female provider. The provider gender was missing for 551 patients (corresponding to 97 providers); these patients were removed from models. The total number of providers was 1707 and the median number of respondents per provider was 3 [IQR: 1; 7]. The patient experience scores ranged from a mean of 59.13 for “Talked worry and stress” to a mean of 94.32 for “Communication” (Table 2).

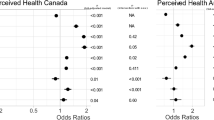

We assessed whether gender concordance (patient and provider had the same gender) was associated with average patient ratings. In these analyses, there were no statistically significant differences on any patient experience score between those who had a gender concordant relationship with their provider vs. not (all p ≥ 0.10; see Table 3 for estimates and 95% CI).

Female patients had more negative perceptions of their provider’s timely care provided (− 1.12, p = 0.006), and of the courtesy of the non-medical staff (− 2.33, p < 0.0001), compared to male patients. Female patients also were more likely to report a conversation with their provider in the last 6 months that focused on the patients’ worries and stress (3.11, p = 0.002).

There were no significant differences between female and male patients’ perceptions of physician communication (p = 0.38), coordination (p = 0.81), or overall provider rating (p = 0.27). Female patients were also no more likely to report differences in their ability to access mental health services and treatments (p = 0.97), in their doctor keeping track of specialist appointments (p = 0.37), or in receiving explanation of after-hours resources (p = 0.22).

Discussion

The results of this study do not support the speculation that there is an association between patient–physician gender concordance and patient experiences. We did find, however, that females were less likely to have better patient experience scores for some measures (timeliness of provider care, courtesy of the medical staff), when compared to males. Female patients were also more likely to recount conversations with their physicians surrounding worry and stress. It is possible that these physician behaviors are influenced in part by patient behaviors, consistent with previous findings suggesting that patient behavior differs by gender.

There are no universally accepted methods for assessing the practical significance of differences in CAHPS scores, although multiple approaches have been proposed,45 such as indexing by the distribution of patient experience measures or indexing measures against an external anchor, such as the likelihood of disenrollment.46 For example, as Quigley and colleagues45 have noted, some have used a threshold of 1 point for small and 3 points for medium on a 0–100 score range.47 Using that standard, the gender differences would be considered small (Timely care) to medium (Talked worry and stress) with the coefficient for Courteous staff between small and medium.

A major limitation of this study is that it was an observational study as opposed to an experiment or a study using scripted patients, videotaping, or assessments by independent observers. Thus, we were not able to rule out the possibility that physician behaviors were influenced by patient behaviors and/or preferences and we were not able to control for selection effects. That is, patients may select clinicians who have communication styles that they value. For example, one study found that when physician reviews endorse a primary care physician’s technical skills, people perceived a female physician to be more interpersonally competent and choose a female physician.48 Also, it is possible that concordance or discordance produces differences in patient experiences not captured by these measures.20 The low response rates to the survey is another potential limitation.

This study adds to the literature exploring how patient and provider gender are related to patient experiences. The study is noteworthy in that it involved a large sample of clinicians and patients and used a standardized survey (CAHPS) for assessing communication experiences. It is unique in that it focused on the experiences of Medicaid patients receiving outpatient treatment. Though the literature has identified gender differences in both clinician and patient behavior and some studies have found effects related to gender concordance, this study did not find any such effects and differences in experiences by patient gender were modest.

References

Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Cleary PD, Zaslavsky AM, Hays RD. Should health care providers be accountable for patients’ care experiences? J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(2):253-256.

Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev 2014;71(5):522-554.

Cleary PD. Evolving concepts of patient-centered care and the assessment of patient care experiences: Optimism and opposition. J Health Polit Policy Law 2016;41(4):675-696.

Freed LH, Ellen JM, Irwin CE, Millstein SG. Determinants of adolescents’ satisfaction with health care providers and intentions to keep follow-up appointments. J Adolesc Health 1998;22(6):475-479.

Bartlett EE, Grayson M, Barker R, Levine DM, Golden A, Libber S. The effects of physician communications skills on patient satisfaction; Recall, and adherence. J Chronic Dis 1984;37(9):755-764.

Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patients' satisfaction and reported acceptance of advice in general practice. J Royal College Gen Practitioners 1975;25(157):558-566.

Harris LE, Luft FC, Rudy DW, Tierney WM. Correlates of health care satisfaction in inner-city patients with hypertension and chronic renal insufficiency. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(12):1639-1645.

Bhanu P. Patient satisfaction. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(3):151-155.

Fremont AM, Bird CE. Social and psychological factors, physiological processes, and physical health. In: Fremont A, Conrad P, Bird C, eds. Handbook of Medical Sociology. 5th. New York: Prentice Hall; 2000.

Meterko M, Wright S, Lin H, Lowy E, Cleary PD. Mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the influences of patient-centered care and evidence-based medicine. Health Serv Res 2010;45(95):1188-1204.

Landen CN, Younger NO, Collins Sharp BA, Underwood PB. Cancer patients' satisfaction with physicians: Princess Margaret hospital satisfaction with doctor questionnaire results. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188(5):1177-1179.

Blanchard CG, Labrecque MS, Ruckdeschel JC, Blanchard EB. Physician behaviors, patient perceptions, and patient characteristics as predictors of satisfaction of hospitalized adult cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;65(1):186-192.

Jefferson L, Bloor K, Birks Y, Hewitt C, Bland M. Effect of physicians' gender on communication and consultation length: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy 2013;18(4):242-248.

Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician Gender Effects in Medical CommunicationA Meta-analytic Review. JAMA 2002;288(6):756-764.

Nicolai J, Demmel R. The impact of gender stereotypes on the evaluation of general practitioners’ communication skills: An experimental study using transcripts of physician–patient encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2007;69(1):200-205.

Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor–patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns 2009;76(3):356-360.

Hall JA, Roter DL. Medical communication and gender: a summary of research. J Gender Specif Med 1998;1(2):39-42.

Bertakis KD, Franks P, Azari R. Effects of physician gender on patient satisfaction. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 2003;58(2):69-75.

Yang HY, Chen HJ, Marsteller JA, Liang L, Shi L, Wang Y. Patient-health care professional gender or race/ethnicity concordance and its association with weight-related advice in the United States. Patient Educ Couns 2015;99(2):271-278.

Schmittdiel J, Grumbach K, Selby JV, Quesenberry CP. Effect of physician and patient gender concordance on patient satisfaction and preventive care practices. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15(11):761-769.

Pratto F, Sidanius J, Stallworth LM, Malle BF. Social dominance orientation: a personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994;67(4):741-763.

Carrard V, Schmid Mast M. Gender in patient-physician interactions. In: Faniko K, Lorenzi-Cioldi F, Sarrasin O, Mayor E, eds. Gender and social hierarchies: Perspectives from social psychology. Philadelphia: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group 2016:58-71.

Keating NL, Green DC, Kao AC, Gazmararian JA, Wu VY, Cleary PD. How are patients' specific ambulatory experiences related to trust, satisfaction, and considering changing physicians? J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:29-39.

Batalha L, Reynolds KJ, Newbigin CA. All else being equal: are men always higher in social dominance orientation than women? Eur J Soc Psychol 2011;41:796-806.

Derose KP, Hays RD, McCaffrey DF, Baker DW. Does physician gender affect satisfaction of men and women visiting the emergency department? J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(4):218-226.

Chekijian S, Kinsman J, Taylor RA, et al. Association between patient-physician gender concordance and patient experience scores. Is there gender bias? Am J Emerg Med 2020.

Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient-physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2018;115(34):8569.

Kaplan SH, Gandek B, Greenfield S, Rogers W, Ware JE. Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians' participatory decision-making style: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care 1995:1176-1187.

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care: the influence of patient and resident physician gender and gender concordance in primary care. J Women's Health 2012;21(3):326-333.

Malhotra J, Rotter D, Tsui J, Llanos AAM, Balasubramanian BA, Demissie K. Impact of Patient-Provider Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Concordance on Cancer Screening: Findings from Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 2017;26(12):1804-1811.

Beran MS, Cunningham W, Landon BE, Wilson IB, Wong MD. Clinician gender is more important than gender concordance in quality of HIV care. Gender Med 2007;4(1):72-84.

Crawford D, Paranji S, Chandra S, Wright S, Kisuule F. The effect of racial and gender concordance between physicians and patients on the assessment of hospitalist performance: a pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19(1):247.

Rogo-Gupta LJ, Haunschild C, Altamirano J, Maldonado YA, Fassiotto M. Physician Gender Is Associated with Press Ganey Patient Satisfaction Scores in Outpatient Gynecology. Womens Health Issues 2018;28(3):281-285.

Bischoff A, Hudelson P, Bovier PA. Doctor–Patient Gender Concordance and Patient Satisfaction in Interpreter-Mediated Consultations: An Exploratory Study. J Travel Med 2008;15(1):1-5.

Roter DL, Erby LH, Adams A, et al. Talking about depression: An analogue study of physician gender and communication style on patient disclosures. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96(3):339-345.

Gross R, Mcneill R, Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Jatrana S, Crampton P. The association of gender concordance and primary care physicians' perceptions of their patients. Women Health 2008;48(2):123-144.

Christen RN, Alder J, Bitzer J. Gender differences in physicians' communicative skills and their influence on patient satisfaction in gynaecological outpatient consultations. Soc Sci Med 2008;66(7):1474-1483.

Janssen SM, Lagro-Janssen ALM. Physician's gender, communication style, patient preferences and patient satisfaction in gynecology and obstetrics: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89(2):221-226.

NAMCS. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2016 National Summary Tables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

Scholle SH, Vuong O, Ding L, et al. Development of and Field Test Results for the CAHPS PCMH Survey. Med Care 2012;50:S2-S10.

Zaslavsky AM, Zaborski LB, Ding L, Shaul JA, Cioffi MJ, Cleary PD. Adjusting performance measures to ensure equitable plan comparisons. Health Care Finance Rev 2001;22(3):109-126.

Gelman A. Struggles with survey weighting and regression modeling. Stat Sci 2007;22(2):156-164.

Kott. Clarrifying somew issues in the regression analysis of survey data. Surv Res Meth 2007;1(1):11-18.

Winship C, Radbill L. Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociol Methods Res 1994;23(2):230-257.

Quigley DHD, Elliott MN, Metodij CM, Hays RD. Quantifying Magnitude of Differences in Patient Experiences with Healthcare Measures. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2).

Lied TR, Sheingold SH, Landon BE, Shaul JA, Cleary PD. Beneficiary reported experience and voluntary disenrollment in Medicare managed care. Health Care Finance Rev 2003;25(1):55-66.

Paddison CA, Elliott MN, Weech-Maldonado R, Hays RD. Experiences of Ccare among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD: Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey results. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;61(3):440-449.

Li S, Lee-Won RJ, McKnight J. Effects of Online Physician Reviews and Physician Gender on Perceptions of Physician Skills and Primary Care Physician (PCP) Selection. Health Commun 2019;34(11):1250-1258.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services, or any of its agencies.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a cooperative agreement from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (#U18HS016978) and a Grant (#1G1-CMS-331630-01-05) from the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior presentations: No prior presentations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prasad, T., Buta, E. & Cleary, P.D. Is Patient–Physician Gender Concordance Related to the Quality of Patient Care Experiences?. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 3058–3063 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06411-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06411-y