Abstract

Background

Hypertensive urgency (HU), defined as acute severe uncontrolled hypertension without end-organ damage, is a common condition. Despite its association with long-term morbidity and mortality, guidance regarding immediate management is sparse. Our objective was to summarize the evidence examining the effects of antihypertensive medications to treat.

Methods

We searched the PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Embase through May 2016. Study selection: We evaluated prospective controlled clinical trials, case–control studies, and cohort studies of HU in emergency room (ER) or clinic settings. We initially identified 11,223 published articles. We reviewed 10,748 titles and abstracts and identified 538 eligible articles. We assessed the full text for eligibility and included 31 articles written in English that were clinical trials or cohort studies and provided blood pressure data within 48 h of treatment. Studies were appraised for risk of bias using components recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. The main outcome measured was blood pressure change with antihypertensive medications. Since studies were too diverse both clinically and methodologically to combine in a meta-analysis, tabular data and a narrative synthesis of studies are presented.

Results

We identified only 20 double-blind randomized controlled trials and 12 cohort studies, with 262 participants in prospective controlled trials. However, we could not pool the results of studies. In addition, comorbidities and their potential contribution to long-term treatment of these subjects were not adequately addressed in any of the reviewed studies.

Conclusions

Longitudinal studies are still needed to determine how best to lower blood pressure in patients with HU. Longer-term management of individuals who have experienced HU continues to be an area requiring further study, especially as applicable to care from the generalist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Hypertensive urgency (HU) is defined as systolic blood pressure of at least 180 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure of at least 110 mmHg, without associated end-organ damage.1 Patients with HU may be completely asymptomatic or may present with symptoms such as headache, epistaxis, faintness, malaise, psychomotor agitation, nausea, or vomiting.2

Up to 65 million Americans have hypertension; about 1% will have an episode of HU during their lives. The prevalence of HU in emergency room (ER) or office settings is estimated at 3–5%.3, 4 In a recent cohort study, cardiovascular events were found to occur in less than 1% of patients within a 6-month period.4

Guidance for immediate management of HU is unclear, since there is no consensus on the optimal target for acute blood pressure reduction or the time frame for achieving a normal blood pressure range. Most patients receive drug therapy for elevated blood pressure within the first 48 h of presentation.2,3,–4 Knowledge of the effectiveness and safety of different medication choices and associated comorbidities is crucial for clinicians, especially generalists.

The aim of this systematic review is to summarize evidence of the benefits and harms associated with antihypertensive medications used to treat HU in adults, either in the clinic or ER. This systematic review is intended for a broad audience, including clinicians—especially general internists—along with policymakers and funding agencies, professional societies developing clinical practice guidelines, patients and their care providers, and researchers.

METHODS

Eligibility Criteria

We defined HU as severe hypertension without evidence of acute end-organ damage. We included studies with non-pregnant adults with systolic blood pressure (SBP) > 179 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) > 109 mmHg, with no end-organ damage. Because of inconsistent terminology, we selected studies based on the above blood pressure criteria. We included both clinic and ER settings in the search, but excluded studies where patients were hospitalized.

Data Sources and Search

Following the PRISMA guidelines,5 and in collaboration with a librarian (JT), two reviewers (CLC, KO) searched the literature using PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Embase. The medical librarian created search strategies with standardized terms and keywords. We excluded case reports, letters, and editorials. Searches were limited to English-language publications and to human studies using the limits provided by the databases. The “human” filter recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions6 was used in PubMed. Studies on pulmonary hypertension were excluded. The gray literature was also searched utilizing Google Scholar. In addition, one expert (PD) identified key literature for the review. All search results were exported to EndNote. Using the EndNote duplicate locator, 4861 duplicate articles were removed. The librarian updated the search in May 2016, and all searches were completed in July 2016. The full search strategy is shown in Appendix A.

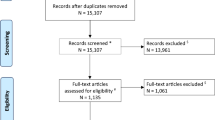

Two evaluators (CLC and KO) independently identified and screened articles for inclusion. Reference lists of studies were manually scanned, and cited references were screened by each evaluator (Fig. 1).

Study Selection

Studies that 1) reported on adults with HU who received pharmacologic therapy in outpatient settings (clinic or ER) and 2) reported initial and subsequent blood pressure values within 48 h of medication administration were reviewed. Studies were excluded if they included animals, pediatric or pregnant patients, or the presence of acute end-organ damage. Because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibits the use of nifedipine for acute management of elevated blood pressure, articles that included only this drug were also excluded (532 studies).7

Primary outcome(s): Given the lack of consensus regarding the blood pressure reduction goal when treating HU, most studies did not report dichotomous outcomes. The primary measures of treatment efficacy were reduction in SBP, DBP, and mean arterial pressure (MAP; in mmHg) within 48 h of pharmacologic treatment.

Secondary outcomes: We extracted adverse effects including headache, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension, stroke, transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, angina, heart failure, pulmonary edema, arrhythmia, renal impairment, new-onset proteinuria, and hospitalization. None of the studies reported on cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Data extraction: Using standardized Excel forms, four groups of two investigators each (JLW, AJC, KO, DJ, CLC, AA, BB, CH) independently extracted data including the author, country, year, study type, setting, sample size, demographics, medications, details of treatment, primary outcome, adverse effects, and initial and subsequent blood pressure values. The team calculated MAP values when not explicitly calculated by the authors.

Two members of the team independently graded the strength of clinical data and subsequent recommendations for treatment of patients with HU according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence. Any discrepancies were resolved after a joint review and discussion with a third reviewer. Levels of evidence were as follows: level 1A, systematic reviews (with homogeneity of randomized clinical trials); level 1B, individual randomized clinical trials (with narrow confidence intervals); level 2A, systematic reviews (with homogeneity of cohort studies); and level 2B, individual cohort studies (including low-quality randomized clinical trials). Grades of recommendation are as follows: A = consistent level 1 studies; B = consistent level 2 or 3 studies, or extrapolations from level 1 studies; C = level 4 studies or extrapolations from level 2 or 3 studies; and D = level 5 evidence or inconsistent or inconclusive studies of any level. Studies with a high loss to follow-up were flagged.

Risk of Bias Assessment

For controlled trials, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment tool. For cohort studies, we used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale to assess study quality.

Data Synthesis

We could not combine results statistically because of heterogeneity among interventions and outcome measures. Furthermore, studies often lacked clearly defined primary outcomes. Therefore, we qualitatively synthesized results by antihypertensive medication class and created tables summarizing the evidence across all studies reviewed.

RESULTS

Our search strategy identified 11,223 published articles. We reviewed 10,748 titles and abstracts (after duplicates were removed) and identified 538 eligible articles. We identified 20 double-blind randomized controlled trials and 13 cohort studies, with 262 participants in prospective controlled trials (Fig. 1). After applying our eligibility criteria to the full texts of these articles, we included 31 English-language articles (Fig. 1). We included studies with nifedipine only if it was included as a comparison drug. We excluded the results of the nifedipine arm because of its black box warning in the management of HU.

The characteristics of included trials are summarized in Table 1. Studies were generally characterized by small sample size, different timing of the effects of antihypertensive therapies (0.17–24 h), and short-term follow-up. Most recent studies were conducted outside the United States.

We compiled the blood pressure effects by antihypertensive class (Table 2) and their reported side effects:

Calcium Channel Blockers

Seven calcium channel blockers were studied in 14 trials.8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,–20 Nicardipine and nifedipine were the most commonly studied (three trials15, 16, 20 and four trials,8, 11, 19, 21 respectively). Isradipine and lacidipine each had two studies,8,9,–10, 13, 19 and amlodipine, nitrendipine, and verapamil each had one study.12,13,–14

Amlodipine (5 or 10 mg PO) was evaluated in one small (n = 46) retrospective cohort.14 Both doses significantly reduced the MAP at 1 h (from 140 and 148 to 103 and 131, respectively). No side effects were reported. Isradipine was investigated in two trials, one a prospective cohort10 and the other an RCT,9 which found that PO doses ranging from 1.25 to 5 mg reduced SBP from 196–204 to 155–165 at 2 h. Reported side effects with isradipine were dizziness and nausea. In four trials,8, 15, 16, 19 lacidipine (4 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg), in SLl or PO formulations, significantly reduced SBP, from 238–186 to 178–145, over 2–24 h. Four trials of nicardipine in various formulations significantly reduced SBP over 1–2 h, from 186–238 to 161–163. Reported side effects from nicardipine were mild headache, hypotension, orthostasis, chest pain, and tachycardia. In single trials, nitrendipine 5 mg PO (n = 85) reduced SBP from 228 to 156 over 2–8 h,22 and verapamil SL reduced SBP significantly over 1–2 h, with 80 mg more effective than 40 mg. Reported side effects with verapamil were decreased heart rate and headache.13

ACE Inhibitors

There were nine trials of ace inhibitors (one retrospective cohort,14 two prospective cohorts,23, 24 five RCTs,16, 25,26,27,–28 one non-randomized controlled trial29). All used captopril in doses ranging from 6.25 to 25 mg in both PO and SL formulations. SBP values were reduced from 244–198 to 177–144 at 0.17–12 h of captopril administration, with greater BP reduction seen using higher doses (25 mg).

Side effects reported with captopril were dizziness, headache, nausea and vomiting,24 dry mouth, vertigo,15 and flushing26.

Beta-Blockers

There were five trials of beta blockers (three prospective cohorts30,31,–32 and two RCTs18, 33). Labetalol was studied in doses ranging from 20 to 300 mg in both IV and PO formulations. Blood pressure values were reduced after 0.33–24 h of labetalol administration in all studies. Labetalol PO was investigated in only one small RCT (n = 10), which found that the mean PO dose of 221 mg reduced SBP from 195 to 154 at 4 h. Side effects reported with labetalol were dizziness,31, 33 drowsiness,33 headache,33 bradycardia,31 and pain at the injection site.32

Centrally Acting Antihypertensives

Two centrally acting agents, clonidine and ketanserin, were studied in seven trials. Clonidine was investigated in six trials (one prospective cohort,34 one retrospective cohort,35 four RCTs11, 12, 33, 36), which found that PO doses ranging from 0.1 to 0.6 mg reduced SBP from 204–196 to 165–155 at 2 h. Side effects reported with the use of clonidine were hypotension, orthostasis, impotence, sedation,37 dry mouth,33,36 mild transient drowsiness, and lower heart rate (average 6.2 beats/min).34

Ketanserin (unavailable in the U.S.) was studied in one RCT, also reducing BP after IV and SL administration. Somnolence was reported.11

Vasodilators

Six vasodilators were studied across nine trials. Urapidil and diazoxide were the most commonly studied (three25, 38, 39 and two trials, respectively40, 41). Fenoldopam,17 hydralazine,14 nitroglycerin,26 and nitroprusside17 were each evaluated once. In three trials, urapidil in IV or PO formulations significantly reduced SBP from 215–165 to 179–132 over 0.5–12 h. Side effects reported with urapidil were nausea, vomiting, drowsiness,39 headache, and orthostatic hypotension.38

Diazoxide (150–1290 mg IV) was investigated in two prospective cohort studies,41, 42 which found that 150–1290-mg IV doses rapidly reduced SBP, from 214–225 to 187–159 in less than 1 h. Side effects reported with diazoxide were uremia, acute pulmonary edema,40 palpitations, transient hemiparesis,42 pain at the site of IV infusion, a mild increase in heart rate, atrial tachycardia, and chest pain.41 In single trials, IV fenoldopam (n = 90) at a mean dose of 0.41 mcg/kg/min reduced SBP from 212 to 178, hydralazine (n = 19) reduced MAP from 244 to 126 at 0.5 h, and nitroglycerin (n = 40) reduced SBP from 190 to 150 at 1 h.

Combinations of Antihypertensives

Combinations of agents were studied in two trials: labetalol plus furosemide and clonidine plus chlorthalidone. Labetalol 300 mg PO plus Lasix 20 mg IV was evaluated in one small (n = 16) prospective cohort,43 which showed a decrease in SBP from 206 to 154 at 3 h. Clonidine plus chlorthalidone was investigated in one RTC,37 which found that PO clonidine doses of 0.2–0.8 mg plus chlorthalidone 25 mg reduced SBP from 193–182 to 142–137 at 24 h.

Direct Comparisons

SL and PO nifedipine were the most commonly studied antihypertensives (four trials), with two comparisons against lacidipine (one prospective cohort,8 one RCT19), one against ketanserin (RCT11), and one against captopril and nitroglycerin (RCT26). Captopril was evaluated in four comparative trials: with amlodipine, hydralazine and nifedipine (one retrospective cohort14), urapidil (one RCT25 and one prospective cohort29), and with nitroglycerin and nifedipine (one RCT26). Clonidine was compared with labetalol (one RCT33) and nitrendipine (one RCT12).

One direct comparison study (RCT17) evaluated fenoldopam and nitroprusside.

When captopril was compared to amlodipine, hydralazine, and nifedipine in a retrospective cohort study,14 there were no significant differences between these medications in their effect on BP reduction (p = 0.513). Captopril was superior to sublingual nitroglycerin in the first hour following administration (p = 0.001).26

In two studies comparing captopril and urapidil,25, 29 both drugs were found to effectively lower blood pressure within 1 h29 and at 12 h25 (p = 0.38/0.40).

When fenoldopam and nitroprusside were compared,17 the two antihypertensive agents were equivalent in controlling and maintaining BP. The adverse effect profiles of the drugs were similar: headache, dizziness, flushing, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, hyperhidrosis, and hypokalemia.

Clonidine and labetalol were compared in an RCT,33 with a similar reduction in blood pressure at 6 h and similar side effect profiles. Sedation, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, and dry mouth were reported with clonidine; dizziness, drowsiness, and headache with labetalol.

Nitrendipine and IV clonidine were compared in one RCT,12 with similar reductions in BP up to 8 h. Side effects reported with nitrendipine were flushing and headache, and with clonidine were dizziness, somnolence, and bradycardia.

Risk of bias is summarized in Table 3. Most studies had unclear quality control standards regarding blood pressure measurements and excluded patients with significant comorbidities, such as chronic kidney disease,15, 34,35,–36, 38, 41 which are seen frequently in patients with hypertension.

Among the controlled trials, only those by Komsuoglu,16 Woisetschlaeger,25 and Just35 had a low risk of bias for both the study design (random sequence generation and concealment of allocation) and the primary clinical outcome (blinding of outcome assessor).

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review of HU, the optimal choice of antihypertensive agent remains unclear (level 2B). Many agents demonstrated blood pressure-lowering benefit: captopril, labetalol, clonidine, amlodipine, verapamil, nitrendipine, isradipine, nifedipine, nitroglycerin, hydralazine, chlorthalidone, furosemide, diazoxide, nitroprusside, and fenoldopam. Other drugs that lowered blood pressure but are unavailable in the U.S. include lacidipine, ketanserin, and urapidil. Clinical choices in the setting of HU seemed to broaden as we conducted our extensive literature search. Side effects ranged from mild (dizziness, headache, nausea and vomiting, dry mouth, mild tachycardia, and sedation) to severe (hypotension, transient ischemic attack, uremia, and acute pulmonary edema).

Most studies limited data collection to the first few hours after initial presentation, which is not sufficient to assess morbidity and mortality.3 Studies were too clinically and methodologically diverse for a meta-analysis, and those that met our criteria for this systematic review included few patients. Most studies excluded patients with significant comorbidities, such as chronic kidney impairment; however, HU is a common complication in patients with associated comorbidities. In light of these factors, the generalizability of our findings is limited. Most studies that met our inclusion criteria provided only surrogate endpoint data, i.e. blood pressure lowering, and were short-term, lacking long-term morbidity and/or mortality outcomes, and providing statistical power only for differences in blood pressure lowering.

Our comprehensive systematic review regarding treatment of outpatient HU includes office and ER settings, limiting data to short-term observations of blood pressure (less than 24 h). This review also included studies based on blood pressure cut-offs, allowing us to distinguish studies that were mislabeled as urgencies or emergencies.

A limitation of this review is that it evaluated only English-language reports. However, Morrison et al.44 found no evidence of a systematic bias from language restrictions in systematic review-based meta-analyses in conventional medicine. We attempted to minimize publication bias by searching the gray literature; we may have missed negative or small(er) studies.

The most recent systematic review of HU, by Souza45 in 2008, included studies in outpatient and inpatient settings. Their Cochrane Review was limited to randomized controlled trials of calcium channel blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Although they excluded commonly used agents (e.g. clonidine, hydralazine, and labetalol3), many other reviews have demonstrated a benefit in blood pressure reduction from these agents. Side effects were problematic mainly for nifedipine and clonidine.

Intravenous medications, although effective, carry added costs, and therefore we do not recommend them; many available oral agents are appropriate alternatives. Some studies included in this review evaluated diuretics.37 However, since HU may be associated with hypovolemia, some recommend avoiding diuretics unless intravascular volume overload is present.37, 46,47,–48

For HU, current data suggest that a 30-min rest may significantly decrease blood pressure. However, many studies in this review did not have patients rest for 30 min prior to intervention.

Most medications used in reports we review here were short-acting. Lowering blood pressure too rapidly in patients with HU may be harmful. In their review, Kessler and Joudeh49 noted that there appears to be no benefit in attaining goal blood pressure within hours to days, and that findings from the VALUE trial50 suggest that lowering blood pressure within a 6 month-period may be a better approach. Therefore, avoidance of rapid-acting agents such as clonidine and nifedipine should be considered.

Other studies have used long-acting antihypertensive agents which have demonstrated morbidity and mortality benefits in hypertension outcomes trials. One such study, conducted by Grassi et al.,46 evaluated the long-acting dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker amlodipine and the ACE inhibitor perindopril in slowly lowering blood pressure toward goal for patients with HU. This study did not meet the inclusion criteria of our review, since it did not report changes in blood pressure within 48 h of treatment.

CONCLUSION

Additional longitudinal studies are needed to determine how best to safely decrease blood pressure in patients with HU. Larger and longer-term studies are also needed, including participants with other common comorbidities. Such research would hopefully provide more guidance to improve both short- and long-term cardiovascular outcome.

References

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52.

Zampaglione B, Pascale C, Marchisio M, CavalloPerin P. Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies. Prevalence and clinical presentation. Hypertension. 1996;27:144–7.

Merlo C, Bally K, Tschudi P, Martina B, Zeller A. Management and outcome of severely elevated blood pressure in primary care: a prospective observational study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142.

Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Presenting With Hypertensive Urgency in the Office Setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:981–8.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, Kowey P. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276:1328–31.

Zampaglione B, Pascale C, Marchisio M, Santoro A. The use of lacidipine in the management of hypertensive crises: a comparative-study with nifedipine. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;23:S116–8.

Saragoca MA, Portela JE, Plavnik F, Ventura RP, Lotaif L, Ramos OL. Isradipine in the treatment of hypertensive crisis in ambulatory patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;19:S76–8.

Saragoca MA, Mulinari RA, Oliveira AF, et al. Parenteral isradipine reduces blood-pressure in hypertensive crisis. Am J Hypertens 1993;6:S112–4.

Sechi LA, Tedde R, Cassisa L, et al. Sublingual and intravenous ketanserin versus sublingual nifedipine in the treatment of severe hypertension: a randomized study. Clin Ther. 1989;11:834–40.

Klocke RK, Kux A, Spaeh F, Blanke P, Blanke R, Wargenau M. Efficacy and tolerability of a new oral formulation of nitrendipine versus intravenous clonidine in patients with hypertensive crisis - a multicenter study in 279 patients. Acta Therapeutica. 1992;18:227–39.

Al-Waili NS, Hasan NA. Efficacy of sublingual verapamil in patients with severe essential hypertension: comparison with sublingual nifedipine. Eur J Med Res. 1999;4:193–8.

Sruamsiri K, Chenthanakij B, Wittayachamnankul B. Management of patients with severe hypertension in emergency department, Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:917–22.

Habib GB, Dunbar LM, Rodrigues R, Neale AC, Friday KJ. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of oral nicardipine in treatment of urgent hypertension: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled clinical-trial. Am Heart J. 1995;129:917–23.

Komsuoglu B, Sengun B, Bayram A, Komsuoglu SS. Treatment of hypertensive urgencies with oral nifedipine, nicardipine, and captopril. Angiology. 1991;42:447–54.

Panacek EA, Bednarczyk EM, Dunbar LM, Foulke GE, Holcslaw TL. Randomized, prospective trial of fenoldopam vs sodium-nitroprusside in the treatment of acute severe hypertension. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:959–65.

McDonald AJ, Yealy DM, Jacobson S. Oral labetalol versus oral nifedipine in hypertensive urgencies in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:460–3.

Sanchez M, Sobrino J, Ribera L, Adrian MJ, Torres M, Coca A. Long-acting lacidipine versus short-acting nifedipine in the treatment of asymptomatic acute blood pressure increase. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;33:479–84.

Clifton G, Cook E, Bienvenu G, Turlapaty P, Wallin JD. Intravenous nicardipine - a dose-finding study in severe hypertensives. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;45:143.

Davidson RC, Bursten SL, Keeley PA, Kenny MA, Stewart DK. Oral nifedipine for the treatment of patients with severe hypertension. Am J Med. 1985;79:26–30.

Santangelo RP, Mroczek WJ. Oral nitrendipine in severe hypertension. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;35:272.

Sahasranam KV, Ravindran KN. Sublingual captopril in severe hypertension. J Assoc Phys India. 1988;36:643–4.

Castro del Castillo A, Rodriguez M, Gonzalez E, Rodriguez F, Estruch J. Dose-response effect of sublingual captopril in hypertensive crises. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;28:667–70.

Woisetschlaeger C, Bur A, Vlcek M, Derhaschnig U, Laggner AN, Hirschl MM. Comparison of intravenous urapidil and oral captopril in patients with hypertensive urgencies. J Human Hypertens. 2006;20:707–9.

Maleki A, Sadeghi M, Zaman M, Tarrahi MJ, Nabatchi B. Nifedipine, Captopril or Sublingual Nitroglycerin, Which can Reduce Blood Pressure the Most? ARYA Atheroscler. 2011;7:102–5.

Gemici K, Baran I, Bakar M, Demircan C, Ozdemir B, Cordan J. Evaluation of the effect of the sublingually administered nifedipine and captopril via transcranial Doppler ultrasonography during hypertensive crisis. Blood Pressure. 2003;12:46–8.

Kaya A, Tatlisu MA, Kaya TK, et al. Sublingual vs. oral captopril in hypertensive crisis. J Emerg Med. 2016;50:108–15.

Salkic S, Brkic S, Batic-Mujanovic O, Ljuca F, Karabasic A, Mustafic S. Emergency Room Treatment of Hypertensive Crises. Medical Arch. 2015;69:302–6.

Joekes AM, Thompson FD. Acute hemodynamic effects of labetalol and its subsequent use as an oral hypotensive agent. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1976;3:789–93.

Lechi A, Picotti GB, Covi G, et al. Intravenous labetalol in severe hypertension. Effects on blood-pressure, plasma-renin activity and catecholamines. Arzneimittel-Forschung/Drug Research. 1981;31(3):524–6.

Huey J, Thomas JP, Hendricks DR, Wehmeyer AE, Johns LJ, Maccosbe PE. Clinical-evaluation of intravenous labetalol for the treatment of hypertensive urgency. Am J Hypertens. 1988;1:S284–9.

Atkin SH, Jaker MA, Beaty P, Quadrel MA, Cuffie C, Sotogreene ML. Oral labetalol versus oral clonidine in the emergency treatment of severe hypertension. Am J Med Sci. 1992;303:9–15.

Greene CS, Gretler DD, Cervenka K, McCoy CE, Brown FD, Murphy MB. Cerebral blood-flow during the acute therapy of severe hypertension with oral clonidine. Am J Emerg Med. 1990;8:293–6.

Just VL, Schrader BJ, Paloucek FP, Hoon TJ, Leikin JB, Bauman JL. Evaluation of drug-therapy for treatment of hypertensive urgencies in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:107–11.

Jaker M, Atkin S, Soto M, Schmid G, Brosch F. Oral nifedipine vs oral clonidine in the treatment of urgent hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:260–5.

Zeller KR, Vonkuhnert L, Matthews C. Rapid reduction of severe asymptomatic hypertension. A prospective, controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:2186–9.

Hirschl MM, Seidler D, Zeiner A, et al. Intravenous urapidil versus sublingual nifedipine in the treatment of hypertensive urgencies. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:653–6.

Bottorff MB, Hoon TJ, Rodman JH, Gerlach PA, Ramanathan KB. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of urapidil in severe hypertension. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;28:420–6.

Finnerty FA, Jr., Kakaviatos N, Tuckman J, Magill J. Clinical evaluation of diazoxide: a new treatment for acute hypertension. Circulation. 1963;28:203–8.

Garrett BN, Kaplan NM. Efficacy of slow infusion of diazoxide in the treatment of severe hypertension without organ hypoperfusion. Am Heart J. 1982;103:390–4.

Ram CVS, Kaplan NM. Individual titration of diazoxide dosage in the treatment of severe hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1979;43:627–30.

Zell-Kanter M, Leikin JB. Oral labetalol in hypertensive urgencies. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:136–8.

Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, et al. The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28:138–44.

Souza LM, Riera R, Saconato H, Demathe A, Atallah AN. Oral drugs for hypertensive urgencies: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127:366–72.

Grassi D, O'Flaherty M, Pellizzari M, et al. Hypertensive urgencies in the emergency department: evaluating blood pressure response to rest and to antihypertensive drugs with different profiles. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10:662–7.

Cherney D, Straus S. Management of patients with hypertensive urgencies and emergencies: A systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:937–45.

Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension—results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. JAMA. 1967;202:1028–34.

Kessler CS, Joudeh Y. Evaluation and treatment of severe asymptomatic hypertension. Am Family Phys. 2010;81:470–6.

Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2022–31.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Pirouz Daeihagh, Associate Professor of Nephrology, Wake Forest Baptist Health, for providing assistance with key literature identification, and Ms. Lisa Porter, Wake Forest Baptist Health, for her administrative support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 33 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Campos, C.L., Herring, C.T., Ali, A.N. et al. Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertensive Urgency in the Outpatient Setting: A Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 539–550 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4277-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4277-6