Abstract

The adverse impact of caregiving on caregivers’ mental health and the positive impact of social participation (SP) on health are both well understood. This study examined the moderating effect of SP on the association between family caregiving and caregivers’ psychological distress (PD). We used longitudinal data from 27,869 individuals born between 1946 and 1955 collected from a 14-wave nationwide survey, which was conducted from 2005 to 2018. We estimated dynamic panel data models, which could control for an individual’s time-invariant attributes in a dynamic framework, to examine how SP moderated the association between informal caregiving and a caregiver’s PD (defined by a Kessler score of 13 or higher). We observed that the onset of caregiving increased the probability of PD by 2.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5%–2.6%) and 1.0% (95% CI: 0.5%–1.6%) for women and men, respectively, compared to 3.4% and 2.8% as the prevalence of PD for women and men, respectively. SP moderated the association between caregiving and a caregiver’s PD by 55.8% (95% CI: 31.9%–79.8%) and 73.5% (95% CI: 36.1%–110.9%) for women and men, respectively. In addition, the moderating effect of SP on a caregiver’s PD increased as the caregiver’s age advanced especially in women. These results suggest the need to keep family caregivers from being socially isolated, especially as they get older.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Extended life expectancy, along with a consistently lower number of multi-child families in advanced countries, has increased the likelihood for middle-aged or older adults to provide informal care to their parents and/or spouses. Informal caregiving is widely considered predictive of the deterioration of caregivers’ mental health. Several studies show that subjective care burden is associated with negative health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and poor self-rated health (Amirkhanyan & Wolf, 2006; Cooper et al., 2007; Del-Pino-Casado et al., 2019; Haley et al., 2020; Hiel et al., 2015; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003; Smith et al., 2011). Therefore, reducing the psychological burden of informal caregivers is challenging, and a necessity in an aging society. This is true even after the introduction of public long-term care schemes.

However, the impact of informal caregiving on caregivers’ mental health may change with age. Older caregivers are more likely to suffer limited financial resources, poorer health conditions (including a higher risk of being frail or disabled), and changes in major life events (such as retirement, child independence, divorce, and separation from family members). All of these factors are likely to put additional psychological pressure on older caregivers. In this regard, “elderly care for the elderly,” or, informal care given by the elderly to the elderly is becoming increasingly important (Fagerström et al., 2020; Ninomiya et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2021). The latest survey, conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW), showed that the proportion of caregivers aged 65 years or above, who were caring for their family members aged 65 or above, increased from 40.6% in 2001 to 59.7% in 2019 in Japan (MHLW, 2020).

SP is a potential mitigating factor of the impact of informal caregiving on caregivers. Many longitudinal studies show that SP experiences at baseline, such as participating in community work, sports/hobby clubs, and voluntary activities, prevent the onset of functional disability (Ashida et al., 2016; Kanamori et al., 2014; Tomioka et al., 2017), PD (Amagasa et al., 2017; Chiao et al., 2011), cognitive impairment (Bourassa et al., 2017; Hsu, 2007), and delayed mortality (Hsu, 2007; Väänänen et al., 2009).

In this study, we examined the moderating effect of SP on the association between caregiving and PD, using longitudinal data. An increasing number of studies have investigated the contribution of SP in the association between informal caregiving and caregivers’ mental health (Mohanty et al., 2020; Schüz et al., 2015; Vlachantoni et al., 2020; Wakui et al., 2012). These studies observed that SP mitigates the adverse impact of SP on caregivers’ psychological well-being, consistent with the conventional view of the favorable impact of SP on health outcomes. Mohanty et al. (2020) further demonstrated that SP is more beneficial for caregivers than non-caregivers, presumably because caregiving results in more activity limitations (Miller & Montgomery, 1990). However, most preceding studies in this field are cross-sectional studies, which could not fully control for endogeneity or simultaneity biases related to an individual’s unobserved attributes. Moreover, the moderating effect of SP may differ between younger and older caregivers, reflecting an age-related change in the opportunities of SP, another issue that has yet to be addressed.

Our longitudinal study encompasses two features that are expected to provide new insights into the psychological relevance of caregiving, for middle-aged or older adults. First, we employed dynamic panel data (DPD) models (Arellano & Bond, 1991), which allowed us to control for an individual’s time-invariant attributes in a dynamic framework of the longitudinal data setting. Compared with a cross-sectional study, this analytical strategy helped us obtain less biased estimation results.

Second, to determine the relevance of “elderly care for the elderly,” we compared the association between caregiving and caregivers’ PD, along with the moderating effect of SP on this association, between younger and older age groups. To this end, we estimated the same DPD model for the 10-year age range group by gradually sliding that age range by one year from 55 to 64 years to 63–72 years, and compared the results across nine age groups.

Methods

Study Sample

We used data obtained from a nationwide 14-wave panel survey, entitled “The Longitudinal Survey of Middle-Aged and Older Adults,” conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) each year from 2005 to 2018. Japan’s Statistics Law required the survey to be reviewed from statistical, legal, ethical, and other viewpoints.

The survey began with a cohort of people aged 50–59 years (born between 1946 and 1955) for the first wave. Samples in the first wave were collected nationwide from individuals between the ages of 50–59 years, in November 2005, through a two-stage random sampling procedure. First, 2515 out of 5280 districts, which had been initially, and randomly selected from approximately 940,000 national census districts, were randomly selected. Second, depending on the population size of each district, 40,877 residents aged 50–59 years as of October 30, 2005, were randomly selected. A total of 34,240 individuals responded (response rate: 83.8%). The second to fourteenth waves were conducted in early November of each year of the period from 2006 to 2018, with no additional sampling. By the fourteenth wave, 20,677 individuals had remained (average attrition rate in each wave: 4.0%). The questionnaire was mailed to the respondents individually, who were then asked to mail it back within a week.

We limited the study sample to individuals who provided no care to any of their older family members in the year prior to each survey, to focus on the short-term association between the onset of caregiving and caregivers’ PD and to mitigate potential simultaneity biases. After excluding respondents with missing key variables, we used the (unbalanced) longitudinal data of 205,532 observations from 27,869 individuals (14,377 women and 13,492 men), over the second to fourteenth waves.

Materials

Caregiving

The survey asked individuals whether and to whom they were providing informal care. We constructed a binary variable of caregiving, by allocating one to the individuals who stated that they were caring for at least one of their parents, parents-in-law, or spouse—regardless of co-residence with them—and zero to the other participants.

Psychological Distress (PD)

We evaluated PD using Kessler 6 (K6) scores (Kessler et al., 2002, 2010). Earlier studies confirmed the reliability, and validity of this score, in the psychological analyses of Japanese people (Furukawa et al., 2008; Sakurai et al., 2011). The survey required the participants to fill in a six-item PD questionnaire. The questionnaire included the following question: “During the past 30 days, how often did you feel a) nervous, b) hopeless, c) restless or fidgety, d) so depressed that nothing could cheer you up, e) that everything was an effort, and f) worthless?” These were rated on a 5-point scale (0 = none of the time to 4 = all of the time). Furthermore, the sum of the reported scores (range: 0–24) was calculated and defined as the K6 score. The Cronbach’s alpha for the entire study sample was 0.897. K6 scores ≥13 indicate the presence of PD in a Japanese sample, as validated by previous studies (Kessler et al., 2010; Sakurai et al., 2011). We constructed a binary variable of PD by allocating one to K6 scores ≥13 and zero to those <13.

Social Participation (SP)

To construct the SP variable, we used the answers to the question regarding participation in social activities, as used in previous studies in Japan (e.g., Oshio & Kan, 2019). The survey asked respondents whether they participated in six types of social activities: (1) hobby or entertainment; (2) sports or physical exercises; (3) community activities; (4) childcare support, or educational or cultural activities; (5) support for the elderly; and (6) others (multiple answers permitted). If the respondents answered yes, they were asked to indicate with whom they participated in each activity by choosing: (1) alone, (2) family members or friends, (3) workplace colleagues, (4) members in a neighborhood association, or (5) members in a non-profit organization or public service corporation. Further, the survey allowed multiple answers. We concluded that the respondents who chose at least one item from (2)–(5), in at least one of the six social activities (1)–(6), engaged in SP. To mitigate simultaneity biases, we focused on whether respondents engaged in SP one year before the concerned wave.

Covariates

Following previous studies that indicate that informal caregiving is associated with socio-demographic/economic status (Cook et al., 2018; Harriss et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021) and health behavior (Gottschalk et al., 2020), we considered marital status, employment status, household expenditure, and tobacco smoking, all of which were time-variant as individual-level covariates. We constructed binary variables for those that had a spouse, a paid job, and those that smoked, by allocating one and zero to those who answered yes and no, respectively. Regarding household spending as a proxy for household income, we divided reported monthly household spending, by the square root of the number of household members, to adjust it by household size (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2015). We categorized them into quartiles and constructed binary variables for each quartile. For respondents who did not provide an answer for household spending, we allocated a binary variable for the unanswered questions. We further included binary variables for each wave to control for wave-specific factors.

Statistical Analysis

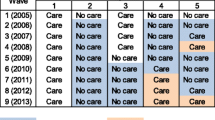

First, we used a descriptive analysis, to describe unadjusted associations across caregiving, SP, and PD, by comparing the prevalence of PD across four types of respondents: non-caregivers with SP, non-caregivers without SP, caregivers with SP, and caregivers without SP. We did this using the respondent-level data obtained in the eighth wave, which was approximately half of the total number of waves.

Regarding the regression analysis, we limited the study sample to those who provided no care in the previous year and estimated a DPD model (Arellano & Bond, 1991) in the form of a linear probability model (LPM) (Battey et al., 2019; Wooldridge, 2013), which linearly predicts the probability of individual i enduring PD in wave t as:

where ui indicates individual i’s time-invariant attributes and is controlled for in the DPD model. We predicted that β1 > 0, β2 < 0, β3 < 0, and β4 > 0. β1 and β1 + β3 represent the association of caregiving without SP, and caregiving with SP, respectively. The ratio β3/β1 indicates the proportion of the association between caregiving and PD moderated by SP. If the interaction term (caregiving × SP) is not included in the regression model, the coefficient of caregiving (β1) represents the overall association between PD and caregiving.

We first estimated the DPD model for men and women separately, using the data over the entire wave (with ages in the range of 51–72 years). We further estimated the same DPD model for the 10-year age range group, by gradually sliding the age range by one year, that is, from 55 to 64 years to 63–72 years. We then compared the results across nine age groups. The purpose of this analysis was to examine how the moderating effect of SP on the association between caregiving and PD changed with age. Note that cohort effects were automatically controlled for in the DPD model and that we controlled for wage-specific factors in regression. We tentatively hypothesized that the moderating effect of SP would increase as caregivers became older, but the results are likely to differ between women and men.

We employed the LPM rather than logistic or probit models, to predict binary variables for PD. We did this by considering the general validity of the LPM (Battey et al., 2019; Wooldridge, 2013), the straightforward interpretation of the coefficient of the interaction term (Chen, 2003), and a substantial reduction in our sample size, owing to the required exclusion of the respondents who experienced no change in the binary variable for PD over the study period, from the logistic fixed-effects model regression (Baltagi, 2013).

Regarding the descriptive and regression analyses, we compared the results between women and men. We did this as previous studies provide evidence of gender differences regarding caregiver stressors (Gallicchio et al., 2002; Lutzky & Knight, 1994; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006). We used the Stata software package (Release 15; STATA Corp, College Station, TX, USA) for all the statistical analyses.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 summarizes the basic features of the respondents in the eighth wave, without controlling for other factors. Panel (1) compares the prevalence of caregiving and SP between men and women, indicating that women were more likely to become caregivers, and had a slightly higher chance of engaging in SP than men. Panel (2) shows that female and male caregivers had a higher risk of suffering PD, while Panel (3) shows that PD was negatively associated with SP for women and men. Lastly, Panel (4) examines how the risk of DP was associated with a combination of caregiving and SP. The risk of PD was reduced by SP, regardless of whether the participants were caregivers or non-caregivers. However, there was a noticeable difference between women and men: a reduction in the risk of suffering PD related to SP, was more remarkable for caregivers (8.6%) than for non-caregivers (3.4%) in women, while a reduction in the risk of suffering PD related to SP was not different between male caregivers and non-caregivers (both 3.3%).

Regression Analysis

Table 2 summarizes the regression results of the entire study sample. The top part of the table presents the results obtained when we did not include the interaction term (caregiving × SP), while the bottom part presents the results with the interaction term.

As in the top part of this table, the estimated coefficients of caregiving (β1) indicated that caregiving corresponded to 2.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5%–2.6%) and 1.0% (95% CI: 0.5%–1.6%) higher probability of suffering PD, for women and men, respectively. These magnitudes were substantial, considering that the actual prevalence of PD accounted for 3.4% and 2.8%, for women and men, respectively.

The negative coefficients of SP (β2) indicate a negative association between SP and PD. The bottom part of Table 2 shows that the estimated coefficients (β3) of the interaction term (caregiving × SP) were negative for women and men. This confirms the moderating effect of SP on the association between caregiving and PD. The proportions of the association moderated by SP accounted for 55.8% (95% CI: 31.9%–79.8%) and 73.5% (95% CI: 36.1%–110.9%) for women and men, respectively.

Table 3 summarizes the estimated associations of the probability of PD with (i) caregiving without SP (β1), (ii) the interaction between caregiving and SP (β3), and (iii) caregiving with SP (β1 + β3), as well as the estimated proportion (%) of the moderating effect of SP (−β3/β1). All of these were obtained from the DPD models for the nine 10-year age ranges. Figure 1 graphically illustrates how the estimated associations of PD (i) caregiving without SP, and (ii) caregiving with SP) changed according to the caregiver’s age. Table 3 and Fig. 1 show that for women, the association between PD and caregiving without SP increased as the caregiver grew older. Meanwhile, the association between PD and caregiving, with SP declined slightly. Therefore, the moderating effect of SP increased with age; the proportion of the effect increased from 49.8% for women aged 55–64 years to 82.0% for those aged 62–71 years. In the case of men, the increase in the association between PD and caregiving without SP with age was much more limited than that for women. The association between PD and caregiving without SP remained largely unchanged and non-significant over the entire age range for men. The proportion of the moderating effect of SP showed an indefinite increase with age, compared to the results regarding women.

Estimated association between psychological distress and caregiving with/without social participation (SP) by age groupa. a Based on the results in Table 3

Discussion

This study examined the extent to which SP moderates the association between caring for older parents or a spouse, and the PD of the caregiver. Unlike most preceding studies, this study employed a DMD model analysis, which allowed us to control for an individual’s time-invariant attributes in a dynamic framework. This approach, in conjunction with the limitation of the sample to those who provided no care in the previous year, mitigated the biases that could not be controlled for when using cross-sectional regression. Additionally, we compared the results across different age groups, considering the possibility of a change in the relevance of SP for the mental health of caregivers as the caregivers aged. The key findings and their implications are summarized as follows.

First, the results confirmed the moderating effect of SP on the association between caregiving and PD, among women and men, consistent with previous studies (Mohanty et al., 2020; Vlachantoni et al., 2020; Wakui et al., 2012). Even after controlling for individual-specific fixed effects and other factors, the DPD model results suggest that SP considerably mitigated the adverse impact of caregiving on caregivers’ mental health. Generally, informal caregivers likely face limited opportunities of SP because they need to provide family care (Miller & Montgomery, 1990). This suggests the possibility that SP may mediate rather than moderate the adverse impact of caregiving on caregivers’ mental health (Sibalija et al., 2020). Hence, public assistance or service utilization should be considered, to help caregivers to provide care, and engage in SP.

Second, the moderating effect of SP increased with age. The adverse impact of caregiving tended to be more serious for older caregivers, especially women. This result highlighted health problems related to elderly care for the elderly.” However, the moderating effect of SP tended to offset the enhanced adverse impact of caregiving, on PD. Consequently, the probability of female caregivers with SP to suffer PD decreased, albeit slightly, with age. Similarly, the probability for male caregivers with SP to suffer PD remained relatively, low and insignificantly different from that of non-caregivers. Many studies have shown the importance of SP for the well-being of older adults (Chiao et al., 2011; Hsu, 2007), presumably because the opportunities of SP are likely to become more limited as people grow older. The results of this study underscored the importance of SP for older caregivers by showing that SP prevented an age-related increase in the adverse impact of caregiving on caregivers’ mental health. An increasing prevalence of “elderly care for the elderly” should raise the need for policy measures, to keep older caregivers socially active, and help them absorb psychological pressure from caregiving. From this viewpoint, the Japanese government has adopted the “community-based comprehensive care system,” which aimed to support older persons and their caregivers (Morikawa, 2014; Song & Tang, 2019). Such policies should continue to play an important role, especially if the public long-term care scheme continues to significantly rely on the commitment of family members to caregiving.

Third, we observed a difference in the moderating effect of SP between women and men. Notably, as shown in Table 2, the proportion of the association moderated by SP (−β3/β1) was relatively more limited for women than for men, for the entire study sample. Considering that the magnitude of the interaction effect between caregiving and SP (|β3|) was almost in the same range, SP’s lower moderating effect for women can be accounted for, by a closer association between caregiving and PD, which is reflected in a higher value of β1, for women. This occurs partly because women render more intensive caregiving. Hence, the lower moderating effect of SP for women did not indicate the limited importance of SP for women. As shown in Fig. 1, this effect increased substantially, as female caregivers got older. Meanwhile, the results showed a more limited increase in the moderating effect of SP for men, as they got older. This may imply that compared with women, a man spends longer in their workplace, which is likely to reduce the chances of enhancing SP. However, it is safe to say that these sex differences will decline over time, as women will continue working longer, and as full-time workers.

This study has several limitations, and many issues remain to be addressed. First, owing to limited information from the dataset, we did not sufficiently consider the extent, or the usage of long-term care assistance, which may have confounded the association between caregiving and PD and contributed to the differences in the abovementioned results of the women and men. Second, we did not fully address the potential endogeneity of SP. The DPD model analysis controlled for the confounding effects of an individual’s attributes on the associations between key variables. However, we could not exclude the possibility that caregiving affects SP during the caregiving process. Third, we did not examine the evolution of the PD caregivers endure over time. Instead, we focused on the short-term association between the onset of caregiving and caregivers’ PD to mitigate potential simultaneity biases. Going forward, we should extend the analysis to the evolution of caregivers’ PD over time (Nieboer et al., 1998). To examine this, a two-way interaction with SP is necessary, as mentioned above. In addition to these methodological limitations, studies should be careful when generalizing the results. The relevance of caregiving and caregivers’ mental health may depend heavily on formal long-term care provisions, family care norms, and other socio-cultural backgrounds (Verbake 2018).

Conclusions

This study confirmed the moderating effect of SP on the association between family caregiving and caregivers’ PD for both women and men. The results also confirmed that this effect prevented further deterioration of PD with age, suggesting the need to keep older caregivers from becoming socially isolated.

References

Amagasa, S., Fukushima, N., Kikuchi, H., Oka, K., Takamiya, T., Odagiri, Y., & Inoue, S. (2017). Types of social participation and psychological distress in Japanese older adults: A five-year cohort study. PLoS One, 12(4), e0175392. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175392

Amirkhanyan, A. A., & Wolf, D. A. (2006). Parent care and the stress process: Findings from panel data. Journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(5), S248–S255. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.5.S248

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968

Ashida, T., Kondo, N., & Kondo, K. (2016). Social participation and the onset of functional disability by socioeconomic status and activity type: The JAGES cohort study. Preventive Medicine, 89, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.006

Baltagi, B. H. (2013). Econometric analysis of panel data (fifth ed.). Wiley.

Battey, H. S., Cox, D. R., & Jackson, M. V. (2019). On the linear in probability model for binary data. Royal Society Open Science, 6(5), 190067. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190067

Bourassa, K. J., Memel, M., Woolverton, C., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: Comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging and Mental Health, 21(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1081152

Chen, J. J. (2003). Communicating complex information: The interpretation of statistical interaction in multiple logistic regression analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1376–1377; author reply 1377. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.9.1376-a

Chiao, C., Weng, L. J., & Botticello, A. L. (2011). Social participation reduces depressive symptoms among older adults: An 18-year longitudinal analysis in Taiwan. BMC Public Health, 11, 292. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-292

Cook, S. K., Snellings, L., & Cohen, S. A. (2018). Socioeconomic and demographic factors modify observed relationship between caregiving intensity and three dimensions of quality of life in informal adult children caregivers. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0996-6

Cooper, C., Balamurali, T. B., & Livingston, G. (2007). A systematic review of the prevalence and covariates of anxiety in caregivers of people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 19(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610206004297

Del-Pino-Casado, R., Rodríguez Cardosa, M., López-Martínez, C., & Orgeta, V. (2019). The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in carers of older relatives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 14(5), e0217648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217648

Fagerström, C., Elmståhl, S., & Wranker, L. S. (2020). Analyzing the situation of older family caregivers with a focus on health-related quality of life and pain: A cross-sectional cohort study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01321-3

Furukawa, T. A., Kawakami, N., Saitoh, M., Ono, Y., Nakane, Y., Nakamura, Y., et al. (2008). The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the world mental health survey Japan. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 17(3), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.257

Gallicchio, L., Siddiqi, N., Langenberg, P., & Baumgarten, M. (2002). Gender differences in burden and depression among informal caregivers of demented elders in the community. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(2), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.538

Gottschalk, S., König, H. H., & Brettschneider, C. (2020). The association between informal caregiving and behavioral risk factors: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Public Health, 65(6), 911–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01402-6

Hajek, A., & König, H. H. (2018). The relation between personality, informal caregiving, life satisfaction and health-related quality of life: Evidence of a longitudinal study. Quality of Life Research: an International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 27(5), 1249–1256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1787-6

Haley, W. E., Roth, D. L., Sheehan, O. C., Rhodes, J. D., Huang, J., Blinka, M. D., & Howard, V. J. (2020). Effects of transitions to family caregiving on well-being: A longitudinal population-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(12), 2839–2846. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16778

Harriss, E. C., D’Angelo, S., Syddall, H. E., Linaker, C., Cooper, C., & Walker-Bone, K. (2020). Relationships between informal caregiving, health and work in the health and employment after fifty study, England. European Journal of Public Health, 30(4), 799–806. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa078

Hiel, L., Beenackers, M. A., Renders, C. M., Robroek, S. J., Burdorf, A., & Croezen, S. (2015). Providing personal informal care to older European adults: Should we care about the caregivers’ health? Preventive Medicine, 70, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.028

Hsu, H. C. (2007). Does social participation by the elderly reduce mortality and cognitive impairment? Aging and Mental Health, 11(6), 699–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860701366335

Kanamori, S., Kai, Y., Aida, J., Kondo, K., Kawachi, I., Hirai, H., et al. (2014). Social participation and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: The JAGES cohort study. PLoS One, 9(6), e99638. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099638

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006074

Kessler, R. C., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Bromet, E., Cuitan, M., et al. (2010). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: Results from the WHO world mental health (WMH) survey initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19(Suppl 1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.310

Lutzky, S. M., & Knight, B. G. (1994). Explaining gender differences in caregiver distress: The roles of emotional attentiveness and coping styles. Psychology and Aging, 9(4), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.9.4.513

Miller, B., & Montgomery, A. (1990). Family caregivers and limitations in social activities. Research on Aging, 12(1), 72–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027590121004

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2020). Comprehensive survey of living Conditions 2019. Accessed August 31, 2021. from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa19/dl/05.pdf

Mohanty, I., Niyonsenga, T., Cochrane, T., & Rickwood, D. (2020). A multilevel mixed effects analysis of informal carers health in Australia: The role of community participation, social support and trust at small area level. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1801. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09874-0

Morikawa, M. (2014). Towards community-based integrated care: Trends and issues in Japan's long-term care policy. International Journal of Integrated Care, 14, e005. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.1066

Nieboer, A. P., Schulz, R., Matthews, K. A., Scheier, M. F., Ormel, J., & Lindenberg, S. M. (1998). Spousal caregivers’ activity restriction and depression: A model for changes over time. Social Science and Medicine, 47(9), 1361–1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00214-7

Ninomiya, S., Tabuchi, K., Rahman, M. M., & Kobayashi, T. (2019). Factors associated with mental health status among older primary caregivers in Japan. Inquiry: a Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing, 56, 46958019859810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958019859810

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). (2015). It together: Why less inequality benefits all. OECD.

Oshio, T., & Kan, M. (2019). Does social participation accelerate psychological adaptation to health shocks? Evidence from a national longitudinal survey in Japan. Quality of Life Research, 28(8), 2125–2133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02142-8

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(1), P33–P45. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.p33.

Sakurai, K., Nishi, A., Kondo, K., Yanagida, K., & Kawakami, N. (2011). Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 65(5), 434–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x

Schüz, B., Czerniawski, A., Davie, N., Miller, L., Quinn, M. G., King, C., et al. (2015). Leisure time activities and mental health in informal dementia caregivers. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 7(2), 230–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12046

Sibalija, J., Savundranayagam, M. Y., Orange, J. B., & Kloseck, M. (2020). Social support, social participation, and depression among caregivers and non-caregivers in Canada: A population health perspective. Aging and Mental Health, 24(5), 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1544223

Smith, G. R., Williamson, G. M., Miller, L. S., & Schulz, R. (2011). Depression and quality of informal care: A longitudinal investigation of caregiving stressors. Psychology and Aging, 26(3), 584–591. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022263

Song, P., & Tang, W. (2019). The community-based integrated care system in Japan: Health care and nursing care challenges posed by super-aged society. Bioscience Trends, 13(3), 279–281. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2019.01173

Tomioka, K., Kurumatani, N., & Hosoi, H. (2017). Association between social participation and 3-year change in instrumental activities of daily living in community-dwelling elderly adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(1), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14447

Tsai, C. F., Hwang, W. S., Lee, J. J., Wang, W. F., Huang, L. C., Huang, L. K., et al. (2021). Predictors of caregiver burden in aged caregivers of demented older patients. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02007-1

Väänänen, A., Murray, M., Koskinen, A., Vahtera, J., Kouvonen, A., & Kivimäki, M. (2009). Engagement in cultural activities and cause-specific mortality: Prospective cohort study. Preventive Medicine, 49(2–3), 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.026

Verbakel, E. (2018). How to understand informal caregiving patterns in Europe? The role of formal long-term care provisions and family care norms. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(4), 436–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817726197

Vlachantoni, A., Feng, Z., Wang, N., & Evandrou, M. (2020). Social participation and health outcomes among caregivers and noncaregivers in Great Britain. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(12), 1313–1322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464819885528

Wakui, T., Saito, T., Agree, E. M., & Kai, I. (2012). Effects of home, outside leisure, social, and peer activity on psychological health among Japanese family caregivers. Aging and Mental Health, 16(4), 500–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.644263

Wang, Y., Li, J., Ding, L., Feng, Y., Tang, X., Sun, L., & Zhou, C. (2021). The effect of socioeconomic status on informal caregiving for parents among adult married females: Evidence from China. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02094-0

Wooldridge, J. M. (2013). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. 5th international ed.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the MHLW.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was financially supported by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (Grant Number: 20 K01722). The funding body had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The dataset was constructed by T.O., analyses were performed by T.O., and the initial manuscript was prepared by T.O. in cooperation with K.S. The final manuscript was read and approved by T.O. and K.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Data obtained from the Longitudinal Survey of Middle-Aged and Older Adults, a 14-wave panel survey conducted by the Japanese MHLW each year between 2005 and 2018, were used. This survey was officially approved by the Statistics Committee of the Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Approval No: 26103, Statistics Code: 00450045), under the Japan’s Statistics Act, which required that it be reviewed from statistical, legal, ethical, and other viewpoints. Survey data were obtained from the MHLW, with official permission. Therefore, ethical approval was not required in this study.

Consent to Participate

The need for written consent was waived, in line with the Statistics Act (see above for Ethics approval).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oshio, T., Sugiyama, K. Social Participation as a Moderator for Caregivers’ Psychological Distress: a Dynamic Panel Data Model Analysis in Japan. Applied Research Quality Life 17, 1813–1829 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-10007-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-10007-x