Abstract

Social support is consistently associated with positive outcomes for students, in terms of wellbeing and academic achievement. For first year students, social support offers a way to deal with stressors associated with the challenge of transitioning to university. The current research was conducted with a range of first year students (n = 315) early in their first semester in university. Both male and female students reported moderate levels of social support and perceived stress, while those with higher levels of social support reported lower levels of stress. Gender differences were apparent in both the levels and sources of social support that students perceived as available to them. Female students reported higher levels of social support and stress than males, suggesting that university initiatives for enhancing social support and dealing with stress may require a gender-specific focus. The results are discussed in terms of recommendations for developing students’ social supports during first year, in order to mitigate for the experience of stress and to enhance student experience of their educational journey.

Similar content being viewed by others

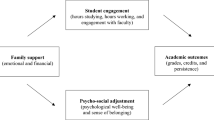

Social support, derived from families, friends and the academic community, can directly impact student experiences during education, with positive impacts on both wellbeing and academic success (Brailovskaia et al., 2018; Maymon et al., 2019; McCoy et al., 2014; Scanlon et al., 2020; Maymon et al., 2019). In contrast, the experience of stress, while recognised as part of the academic experience, can have a detrimental impact on academic outcomes, wellbeing (Berwick & Finkelstein, 2010; Conley et al., 2020; Poots & Cassidy, 2020) and mental health (Liu et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2021). In order to optimally benefit from their educational experiences, students are required to learn to cope effectively with stress (Gustems-Carnicer et al., 2019), and higher levels of social supports have consistently been identified as associated with lower stress levels and a greater ability to manage stressors (Jun et al., 2018; Yildirim et al., 2017; Mishra, 2020). Commencing university presents significant challenges for students, with indications that students are at a higher risk of stress during this period, than throughout the remainder of their programme (Berwick & Finkelstein, 2010; Conley et al., 2020; Demir et al., 2014; Denovan & Macaskill, 2016). Recent research has suggested the need to develop a greater understanding of the quality and sources of social support experienced by students (Maymon et al., 2019; Mishra, 2020), while at the early stages of students, academic career study has been identified as a key period for the development of effective social support systems (Reeve et al., 2013). The research aimed to examine first year student's percetion of social support and the impact of this support on reported stress during this critical phase of transition to university.

Social Support

Social support is a multidimensional concept (Lourel et al., 2013), referring to the social and psychological support an individual receives or perceives as available to them from family, friends and their community (Awang et al., 2014; Zimet et al., 1988). Perceived social support refers to the perception that support would be available if needed (Day & Livingstone, 2003) and comprises emotional and instrumental support (Trepte & Scharkow, 2016). Crucially, the effectiveness of social support is dependent on the match between the source, type, timing and the needs of the individual (Cohen & McKay, 1984; Cutrona & Russell, 1990; Jacobson, 1986). The relationship between social support and positive outcomes has been demonstrated in both quantitative research (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2020; Poots & Cassidy, 2020; Reeve et al., 2013) and qualitative studies (Charalambous, 2019; Scanlon et al., 2020), with students across various disciplines and countries (e.g. Cornelius et al., 2016; Pluut et al., 2015; Walton et al., 2015). The range of social supports that students receive from their families, friends and the academic community can directly influence their ability to deal with the challenges associated with university life (Cage et al., 2021; Mishra, 2020) and is associated with more successful experiences during their education (Maymon et al., 2019; McCoy et al., 2014; Scanlon et al., 2020).

There is substantial evidence highlighting the role of social support in promoting psychological health (Cohen, 2004; Hartung et al., 2015; Santini et al., 2015; Tough et al., 2017; Uchino et al., 2012) and of the protective effect of social support (Haddadi & Besharat, 2010; Hu et al., 2015; Thoits, 2011; Werner-Seidler et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). Higher levels of social support have been found to be associated with improved psychological wellbeing (Glozah, 2013; Poudel et al., 2020; Reeve et al., 2013; Poots & Cassidy, 2020), with students that perceived social support positively found to be at a lower risk for mental health problems (Karaca et al., 2019; Khallad & Jabr, 2016; Terzi, 2008; Yildirim et al., 2008). Social support has consistently been shown to impact depression, anxiety and quality of life for students across various age groups and populations (Ibrahim et al., 2013; Othieno et al., 2014; Hamdan-Mansour & Dawani, 2008; Kirby et al., 2015; Vungkhanching et al., 2017). Higher levels of social support from family and friends have been found to be correlated with greater life satisfaction (Harikandei, 2017) and less loneliness (Lee & Goldstein, 2016). Further to this, social support has been identified as exerting positive peer pressure and social controls on student’s health and risk-taking behaviour (Jessor et al., 2006). This has led to a recognition of social support as a valuable resource for universities in protecting the mental health of students (Baltas & Baltas, 2004; Vungkhanching et al., 2017), with a recent large study (n = 13,189) of students in Germany, Russia and China identifying the importance of resilience and social support as key protective factors for mental health (Brailovskaia et al., 2018).

In addition to the impact on emotional outcomes, social support and personal networks can impact students’ academic performance (Awang et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2012; Brouwer et al., 2016) and have a significant role on higher education success (Mishra, 2020). Social support has been identified as impacting students’ integration into academic life (Cox & Naylor, 2018; Maunder, 2018), which can in turn affect both retention and academic success (Gallop & Bastien, 2016; Masserini & Bini, 2021; Reeve et al., 2013). Family support has consistently been identified as playing an important role in academic persistence (Abukari, 2010; Nelson, 2019; Sosu & Pheunpha, 2019; Theodore et al., 2017), while support derived from peers and support groups is associated with positive academic outcomes (Kim et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018a, b), including enhancing understanding of course materials and clarifying difficult concepts (Collins et al., 2010; Gallop & Bastien, 2016; Masserini & Bini, 2021). In terms of other sources of support, while students may access support from academic staff to a lesser extent than that from other sources (Blair, 2017; Casapulla et al., 2020; Reeve et al., 2013), these relationships are found to be important for both wellbeing and transition to university (Cage et al., 2021; Jun et al., 2018; Maymon et al., 2019; Meehan & Howells, 2017; Reeve et al., 2013). Research has identified that certain programmes due to teaching methods and small group classes may lead to greater peer social support (Jun et al., 2018). The current study included students from a range of disciplines to allow consideration of students from a range of disciplines, with different levels of social support.

Social Support and Stress

The ability to cope with stressors can directly impact students’ academic performance (Reeve et al., 2013; Struthers et al., 2000) and wellbeing (Brailovskaia et al., 2020; Chao, 2012; Karaca et al., 2019; Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Tyssen et al., 2001). Social support has been long established as a moderator of stress (Cohen, 2004; Glozah, 2013; Soman et al., 2016) and to function as an effective coping mechanism for dealing with stressors (Li et al., 2018a, b; Reeve et al., 2013; Yıldırım et al., 2017). Sharing stress with others is suggested to enable one to tolerate stress more easily (Baltas & Baltas, 2004), allowing more effective coping with academic stress (Cohen, 2004; Glozah, 2013; Soman et al., 2016; Wolf et al., 2017; Yıldırım et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2015). Research conducted with a range of student cohorts has indicated that the level of stress experienced by students was significantly predicted by levels of perceived social support (Kirby et al., 2015; Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Naylor et al., 2018; Poots & Cassidy, 2020; Yıldırım et al., 2017). Jumat et al. (2020) argue that students who do not have sufficient protective factors to safeguard from ongoing stress can be at risk of burnout, with social support identified as one mechanism to allow students to deal with the demands of academic life, and later professional life. This research supports findings from other similar research (Kim et al., 2018; Polman et al, 2010) indicating that social support is negatively correlated with student burnout.

Peer social support, in particular, has been identified as buffering the experience of stress (Lee & Goldstein, 2016; Vungkhanching et al., 2017), specifically for younger students (Charalambous, 2020; Warshawski et al., 2018). These findings may be partly explained through student’s perception of the social support available to them from these peer relationships. Day and Livingstone (2003) suggest that one’s perception of their social support network has an essentially greater coping effect than if they receive the support and to exert a stronger effect on mental health than actual social support received (Hefner & Eisenberg, 2009; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2016). The perception of having social support available can provide a buffer in times of stress, increase happiness and enhance psychological wellbeing (e.g. Barrera, 1986; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Winemiller et al., 1993). Peer support, in addition, has the potential to normalise experiences and promote a sense of belonging (Batchelor et al., 2020), as the nature of the support is provided by someone who is similar and equal to the recipient (Kim et al., 2017). In terms of other types of social support, Mamun et al.’s (2019) recent research has indicated that being in a significant relationship was a predictor of higher levels of stress, rather than providing social support. However, the distress identified by the students could be associated with the significant changes to relationships and related social support, as students were living away and spending reduced time with their partner.

There are mixed findings on the levels and impact of social support within the research conducted with students, with indications of differences based on gender, age, discipline and mode of study. Gender has been identified as a significant predictor of social support (Casapulla et al., 2020; Hamdan-Mansour & Dawani, 2008; Park et al., 2015; Soman et al., 2016; Zamani-Alavijeh et al., 2017), with higher levels reported consistently by female students. Jun et al. (2018) reported that the high levels of support among nursing students may be related to gender differences, but also to the nature of the programme and the use of small groups which facilitate the development of close relationships and social support from peers (Brouwer et al., 2016; Poots & Cassidy, 2020). In contrast, however, Zamani-Alavijeh et al. (2017) found that over 60% of medical science students in Iran (n = 763) reported low levels of social support, with females reporting significantly lower levels than male students. These findings suggest that males and female students may have different support needs, but also may perceive source social support differently (Casapulla et al., 2020; Zamani-Alavijeh et al., 2017). While there is a significant body of research developing in this area of studies, they vary significantly in methodology, definition of social support, timing of data collected, population samples, cultural differences and students’ living circumstances, making it difficult to make direct comparisons across studies on the levels of social support available to students.

Similarly, gender differences in perceived stress have been identified, with female students reporting higher levels of stress than males (Backović et al., 2012; Cage et al., 2021; Hamdan-Mansour & Dawani, 2008; McCoy et al., 2014; Park et al., 2015; Polman et al, 2010; Poots & Cassidy, 2020; Zhang et al., 2018). In a recently published longitudinal study of students (n = 5532) in the USA (Conley et al., 2020), female students reported experiencing higher distress, while male students exhibited lower support from friends than females adding to the evidence from previous research (Hamdan-Mansour & Dawani, 2008; Park et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018).

First Year Students and Transition to University

Research conducted in multiple countries has identified the transition to third-level education to be a potential source of stress for students (Cage et al., 2021; Charalambous, 2020; McCoy et al., 2014) and that during their early stages of university, students can experience the highest level of stress than throughout the remainder of their studies (Conley et al., 2020; Demir et al., 2014; Denovan & Macaskill, 2016). While some research indicates that various periods of study such as examinations and placement practice can lead to higher experiences of stress (Sun & Zoriah, 2015), Bewick et al. (2010) have suggested that stress commences in the initial semester for students and does not abate throughout the time in university. There are numerous factors that may explain this, predominantly related to the onset of academic demands, the need to adapt to new circumstances and the significant life and identity changes student make as they transit from adolescence into adulthood (Opoku-Acheampong et al., 2017; Bhandari, 2012; Cage et al., 2021; Charalambous, 2020; Chen et al., 2013; Mašina et al., 2016). Furthermore, the introduction of higher fees and the more competitive employment market have been identified as creating the context for higher levels of stress for students in the UK and Ireland (Money et al., 2017; O.Leary, 2019).

In addition to these challenges, social supports change as students make the transition to university, spend less time with family and friends and are required to adjust to an unfamiliar environment and to develop new social support networks (Bray & Born, 2004; Charalambous, 2020). Social support during the first year of study is consistently associated with enhanced wellbeing (Brailovskaia et al., 2020; Hartung et al., 2015, Mattanah et al., 2012; Poots & Cassidy, 2020; Reeve et al., 2013; Vungkhanching et al., 2017) and positive academic outcomes (Charalambous, 2020; Denny, 2015; Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Mishra, 2020; McGonagle et al., 2014; Van der Zanden et al., 2018; Walton et al., 2015). However, as this period of commencing university is often characterised by transition and exploration, it creates an opportunity for the development of new social supports, alongside new identities (Arnett, 2000). However, there are some indications that students in junior years are more likely to report lower levels of perceived social support, than those in higher years (Chavajay, 2013; Vungkhanching et al., 2017). In line with this, Warshawski et al. (2018) found that students in first year reported higher levels of support from family and friends than those in later stages, along with a greater use of online social support mediums to access social support. These mixed findings in relation to levels of social support may be partly explained by consideration of the various types of social support explored in the studies but do suggest social support from peer may take time to develop as students commence their studies.

Social relationships and support have been identified as one of the main predictors of increased success for students during the transition to university (Cage et al., 2021; Denny, 2015; Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Meehan & Howells, 2017; Van der Zandan et al., 2018). In an Irish context, Scanlon et al. (2020) identified students’ positive experiences of university life often centred on peer relationships and shared interests and aspirations. This is in line with findings from a report by Denny (2015), where students in Ireland highlighted the benefits of mentoring and relationships during the transition to university, and mirrors findings from other longitudinal research conducted with school leavers in Ireland (McCoy et al, 2014). Masserini and Bini (2021) argue that younger and first year students’ social networks help to strengthen students’ academic integration and engagement. This is not surprising as a sense of belonging is recognised as a key concept in the positive experiences of younger students in university and can be enhanced through meaningful interactions with peers and faculty staff (Hausmann et al., 2007; Mishra, 2020). Related to this, Meehan and Howells’ (2017) longitudinal study of student’s satisfaction in the UK identified three key elements of a positive university experience, directly related to the academic staff, the nature of their programme and students’ overall sense of belonging. Maymon et al. (2019) highlighted the importance of social support and specifically the significant role of faculty staff support as contributing to overall wellbeing in the first year experience.

Social support is recognised as an element of the student experience that is easily adaptable during the early stage of student life (Cage et al, 2021; Denny, 2015; Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Scarapicchia et al., 2017; Scanlon et al., 2020). The structure of universities, comprising of residence halls and student organisations, can facilitate the building of such friendships and networks (Mishra, 2020). In addition, there is some evidence to suggest that students who spend less time on campus during their first year reported have less access to social supports (Leese, 2010; McCoy et al., 2014), which can lead to a reduced sense of belonging (Casapulla et al., 2020; Naylor et al., 2018). Naylor et al. (2018) further argue that educators have a significant role in mitigating workload stress for first year students through facilitating the development of social support (Jumat et al., 2020).

Taking all of this into account, there is therefore a growing recognition of the importance of social support in ensuring successful transition to university for students (Cage et al., 2021; Charalambous, 2020; Denny, 2015; Maymon et al., 2019; McCoy & Byrne, 2017a, 2017b; Meehan & Howells, 2017; Van der Zandan et al., 2018). Most universities now offer specific transition programmes and initiatives aimed at enhancing the first year experience for students. However, the focus of programmes are usually on practical and academic elements, rather than stress, coping and resilience with students (Leary & DeRosier, 2012). In addition, in terms of the impact of these initiatives and supports to enable successful transitions, comparisons of institutions within or across countries are relatively rare. Much of the research has focused on academic outcomes and the role of student characteristics and success, which are all defined in various ways (McCoy & Byrne, 2017a, 2017b).

The aim of the current research was to explore first year student experience of stress and social support as they commence their first semester at university. Social support as a multidimensional concept suggests the importance of studying categories and sources, rather than levels alone (Casapulla et al., 2020), and as such the need to explore sources of social support was identified as important in the current study. As student experiences at university do not occur in isolation and instead are impacted by their relationships and supports within and outside university, there is a need for educators to consider students’ relationships and support networks (Mishra, 2020). The current research therefore aimed to identify the main sources of perceived social support available to students and any impact of these supports on stress as students deal with the challenges that accompany the journey into higher education. As social support is associated with students’ ability to tolerate and cope with stressors, a clear understanding of the experience of students can impact educators’ ability to positively impact or reduce stress at this critical time of transition.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 368 students in their first semester at university. Following screening, data was analysed from 161 females (M = 21.12, SD = 6.6) and 151 males (M = 20.46, SD = 5.08), totalling 315 first year students from eight different disciplines who were enrolled in full time programme in one university in Dublin. The students were aged from 18 to 54 years old (M = 20.79). Ethical approval was granted from the Ethics Committee within Technological University Dublin, Blanchardstown for the study.

Measures

Perceived Social Support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988) is a self-report scale, which evaluates perceptions of support from three sources, family, friends and significant other, with higher scores indicate greater perceived social support. Example questions include “My family really tries to help me” or “I can talk about my problems with friends”. The scale is comprised of 12 total statements, and participants rate these on a Likert scale anchored at 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The MSPSS has demonstrated good reliability and validity with alpha values for the subscales and the scale as whole between 85 and 91 (Clara et al., 2003; Zimet et al., 1988). There are no established population norms on the MSPSS, as norms would likely vary on the basis of culture and nationality, as well as age and gender (Zimet et al., 1988). Classification is typically made across groups.

Perceived Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., 1983) is a self-report instrument that evaluates the level of perceived stress during the month leading up to the questionnaire. The scale consists of 10 items with a 5-point response scale where 0 is never, 1 is almost never, 2 is sometimes, 3 is often and 4 is very often. Sample questions include, for example, In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed? The PSS-10 has been used in various international studies to measure perceived stress and the extent to which participants feel that their lives are unpredictable, uncontrollable and overloading (Heath et al., 1999). The total score of the PSS is obtained by summing across all scale items, and a higher score indicates a higher level of perceived stress. The PSS which possesses superior psychometric properties (internal consistency and factor structure) (Cohen & Williamson, 1988) has been widely used in studies with students (see Chao, 2012; Tavolacci et al., 2013). Individual scores on the PSS can range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress. The PSS also allows for classification into low (0–13), moderate 14–26) and high (27–40) stress categories.

Demographics

Participants were asked to provide the following demographic information: age, gender and programme of study (discipline) (Table 1).

Procedure

The survey was distributed via an online survey link to all first year students during October 2019. The students were approached during mandatory classes by the researchers and invited to participate and given the link and provided with time to complete the survey during the class. In total 924 students (total year one students) were approached and 368 participated, representing eight different discipline areas within the student population in the university. Data was collected anonymously via Microsoft Office Forms. Raw data was processed according to standardised scoring and screening procedures for each of the measures. The SPSS220 statistical software package was used for data processing and analysis.

Results

Demographics

Perceived Social Support

The mean level of social support reported by students was within the moderate category (M = 62.64, SD = 14.52). Results show that 32%, 33% and 35% of participants were classified in the low, moderate and high social support categories, respectively. There was a significant difference found in levels of social support between gender (X2 (2,312) = 8.73, p < 0.013) with 42% of female students being in the high social support category compared to 27% of male students. Furthermore 27% of females were categorised as having low social support compared to 37% of males. There was no significant differences (X2 (2,312) = 2.34, p > 0.05) found between older and younger students on measures of perceived social support.

Sources of Social Support

Further analysis of the three subscales within the MPSS revealed significant differences between females and males on social support from significant others (t (310) = 3.87, p < 0.01, two-tailed) but not for friends (p > 0.05) or family (p > 0.05) (Table 1). Females (M = 22.18, SD = 5.35) were found to get more social support from significant others compared to males (M = 19.72, SD = 5.87).

Perceived Stress

The average level of stress in students was M = 19.71 and SD = 7.04, and 66% of students reported moderate levels of stress, with 14% reporting elevated levels of stress. An independent sample t-test indicated that there was a significantly main effect for gender (t (310) = 4.33, p < 0.01, two-tailed), with female students demonstrating higher levels of stress (M = 21.33, SD = 6.43), compared to males (M = 17.97, SD = 7.26) (Fig. 1).

Gender and Stress

A chi-square test of independence was performed to assess the relationship between perceived stress and gender. There was a significant relationship between the variables (X2 (2,312) = 17.17, p < 0.001) with 20% of females being categorised as having high stress and 11% reporting low stress compared to 10% and 27% of males in the high and low stress categories, respectively.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the influence of discipline of study on levels of stress and social support. There was a significant difference found between discipline of study for total perceived stress (F(7,304) = 2.19, p < 0.05) but not for social support (F(7,304) = 1.59, p > 0.05). Post hoc analysis revealed significantly higher levels of stress with students in social care discipline (M = 17.68, SD = 5.63) compared to students in the business discipline (M = 21.64, SD = 6.72).

Perceived Stress and Perceived Social Support

The relationship between perceived social support and perceived stress was investigated using the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. There was a significant moderate, negative correlation between the two variables (r = –0.331, n = 312, p < 0.01) with high levels of perceived social support associated with lower levels of perceived stress (Figs. 2 and 3).

Gender Differences

There was a significant moderate, negative correlation between the two variables (r = –0.419, n = 161, p < 0.01) in female students, with high levels of perceived social support associated with lower levels of perceived stress. A moderate, negative correlation was observed between the two variables for male students (r = –0.349, n = 151, p < 0.01) with high levels of perceived social support associated with lower levels of perceived stress.

Discussion

This research identified that the majority of students reported experiencing stress during the initial weeks of commencing university, with female students reporting significantly higher levels than male students. Gender differences were also observed in both the levels and sources of social support of first year students perceived as available to them (Zamani-Alavijeh et al., 2017). There was a negative correlation observed between students reported levels of social support and experience of stress, similar to previous research (Jun et al., 2018; Kirby et al., 2015; Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Reeve et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2018, Poots & Cassidy, 2020; Vungkhanching et al., 2017) and thereby adding to the evidence suggesting a moderating impact of social support on stress (Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Conley et al., 2020). Significantly, female students who reported higher levels of social support reported lower levels of stress, while they also reported higher levels of stress. This finding highlights the need for educators to further develop supports for students in order to mitigate for increased exposure to stressors during the early stages of transition to university (Conley et al., 2020; Denovan & Macaskill, 2016; Meehan & Howells, 2017; Regehr et al., 2013) and to identify gender differences and the development of targeted initiatives based on these differences.

Social Support

In terms of the sources of social support, there were no significant differences in the origins of support identified by students in the current study. Support derived from family and significant others was however slightly higher than that identified as available from peers, similar to findings reported by Warshawski et al. (2018). The participants were in the early stages of commencing university, and the changes in peer relationships that accompany this period (Scarapicchia et al., 2017; Wilcox et al., 2005) may explain this finding. Peer support has consistently been recognised as central for students (Awang et al., 2014; Brouwer et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2012; Collins et al., 2010; Gallop & Bastien, 2016; Li et al., 2018a, b) and associated with successful transition and integration (Charalambous, 2020; Denny, 2015; Maunder, 2018; Mishra, 2020), sense of belonging (Maunder, 2018; Van der Zanden et al., 2018) and for a positive experience of university life (Scanlon et al., 2020). While the students in the current study clearly identified the role of peer social supports in their lives, the results suggest that there may be scope for educators to consider ways to enhance these levels of peer social support for first year students. Students may spend more time with their peers, than with parents or family members, and as such, it may be even more important to facilitate the development of such interpersonal relationships (Jumat et al., 2020; Vungkhanching et al., 2017). Such an initiative to facilitate the development of peer relationships has been rolled out in the university in which this study took place, with a focus on peer mentoring and enhancing the first year experience. Previous research has identified the impact of such programmes on social support (e.g. Collings et al., 2016); however, data collection in the current study was conducted prior to peer mentoring programme commencement, and as such was not considered in the study.

The results within the study further suggest that students identified family and significant others as important sources of social support. However, in comparison to when students are in school, they are recognised as adults at university, and as such, there can be a greater identification of self-directed peer and faculty-based social supports, rather than on that provided by student families. The findings in the current study suggest that a greater recognition of the role of first year students’ families as a significant source of social support could be recognised further by educators during the transition to university. This focus may include a greater recognition that for younger students and students from communities, successful negotiation of this transition requires ongoing support from families and communities outside of the university (Mishra, 2020). As previous research has identified the impact of family social support derived from ones family on both student’s achievement and wellbeing (Abukari, 2010; Mishra, 2020; Nelson, 2019; Sosu & Pheunpha, 2019; Theodore et al., 2017; Warshawski et al., 2018), the role of family and significant others in students’ lives is important for educators to understand.

Gender differences were observed in the levels of social support students perceived as available, with 42% of females reporting high levels of perceived social support, while only 27% of males reported high levels. While this is consistent with other research (Hamdan-Mansour & Dawani, 2008; Park et al., 2015; Poots & Cassidy, 2020), a comparison to other studies is made difficult due to some studies being comprised of high proportions of single sex samples (e.g. Jun et al., 2018; Karaca et al., 2019; Poots & Cassidy, 2020; Warshawski et al., 2018). Furthermore, the current findings indicated significant gender differences in the sources of social support, with female students reporting significantly higher level of perceived social support from significant others compared to the male students. This finding is in line with research suggesting that males and females may report different support needs and source social support differently (Zamani-Alavijeh et al., 2017). Individual differences in the experience of social support, including choices of support, number of supporters required by students and ways in which they access support, are also relevant (Meehan & Howells, 2017). The gender differences identified in the current study provide additional understanding for educators on how students experience social support and the factors that contribute to it (Mishra, 2020). This knowledge may help the design of targeted interventions for specific groups of students who require additional supports to develop effective social networks (Bewick et al., 2010; Casapulla et al., 2020; Maymon et al., 2019).

Social Support and Stress

In addition to social support, stress experienced at university has been shown to impact student academic outcomes (Charalambous, 2020; Gustems-Carnicer et al., 2019) and wellbeing (Park et al., 2015; Poots & Cassidy, 2020; Van der Zanden et al., 2018) and in particular for first year students (Cage et al., 2021; Conley et al., 2020; Denovan & Macaskill, 2016; Leary & DeRosier, 2012). The majority of first year students in the current study reported a moderate level of stress (66%), with only 19% identifying themselves as falling within the low stress category. The current research therefore supports the findings that the early stages of university are associated with increased risk of stressors (Bewick et al., 2010; Cage et al., 2021; Conley et al., 2020; Denovan & Macaskill, 2016; Vungkhanching et al., 2017). In addition, the students in the current study had not yet commenced periods of high-stake examinations or practice placements which have previously been identified as leading to an increased risk of experiencing stress (Karaca et al., 2019; Wolf et al., 2015). While there was a significant difference in levels of stress reported by students within the disciplines of study, one group of students, within the social care discipline, was identified as having significantly higher level of stress than one of the other disciplines (business). This finding would be in line with similar findings of higher stress levels with students from allied field of study such as nursing and other care-related disciplines (e.g. Jun et al., 2018; Reeve et al., 2013).

Social support has consistently been identified as a mediator of the experience of stress (Jun et al., 2018; Kirby et al., 2015; Poots & Cassidy, 2020; Reeve et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2018) and as having a moderating impact on stress for students in their first year (Conley et al., 2020; Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Park et al., 2015). Our results are in line with these findings, with higher levels of social support associated with lower levels of stress. While the direction of the relationship between social support and stress is not identifiable in the cross-sectional nature of the current research, previous research has consistently identified the positive impact of social support on stress. However, clear gender differences were found in both social support and perceived stress in the current results, with females reporting significantly higher levels of social support and of stress, than male students.

Zhang et al. (2018) have argued that for females, social networks may not always provide adequate levels of social support and indeed a lack of social support can become an additional stressor for some. The results in the current study are also in line with findings from previous research suggesting that the initial stages of transition to university can be more challenging for female students, compared to males (Cage et al., 2021; Charalambous, 2020). This finding may also be interpreted in line with Poots and Cassidy (2020) finding that female students place more expectations on themselves than male students, or to other gender-related differences in recognising and naming social support and stress (Morris, 2020). While recognising that social support and stress are individual experiences, female and male students do appear to experience both social support and stress differently (Zamani-Alavijeh et al., 2017). Gender differences identified in the use of coping strategies (Vungkhanching et al., 2017) and willingness to engage in stress management initiatives (Regehr et al., 2013) further suggest that male and female students may require different interventions to support them during the commencement of their academic journey (Casapulla et al., 2020).

The findings therefore provide further support for enhancing first year students’ abilities to cope with stressful situations, particularly among female students early in their academic career (Gustems-Carnicer et al., 2019; Park et al., 2015). While many universities and programmes offer stress management initiatives for students, these often take place later in students’ studies, rather than during the initial weeks of first semester (Regehr et al., 2013). Related to this, while there is a recognition of the importance of first year orientation and induction programmes for successful transition to university, these programmes often do not directly address coping skills for stressors (Leary & DeRosier, 2012). The current research supports the view that a greater focus on these factors, along with facilitating the development of a range of effective social supports may enhance experience during the initial year of study and help with the initial challenging transition to university.

The current research was conducted with students from a range of different disciplines, while much of the previous research has focused on one discipline of student, and as such, findings are often representative of the specific cohorts of students studied (e.g. nursing students, Karaca et al., 2019; Reeve et al., 2013; engineering students Walton et al., 2015). While there is significant merit in investigating the challenges faced by groups of students in specific programmes, the current research findings provide the perspective of a range of students as they navigate their way in the early stages of university. A greater understanding of the range of students’ needs and experiences has recently been highlighted as important as the diversity of the student population increases (Mishra, 2020). The current research also adds to the body of research exploring the experience of an increasing diverse population of students within the Irish educational system as they transition to third-level education (Denny, 2015; McCoy et al, 2014; Scanlon et al., 2020).

There is a growing awarness of the increased academic demands faced by students, and the role of educators in helping to mitigate for risks associated with student's experience of stress (Casapulla et al., 2020; Gustems-Carnicer et al., 2019; Karaca et al., 2019). An identification of times when challenges may present a greater risk of stress for students allows for the development of protective factors, such as social supports (Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Poots & Cassidy, 2020), and the current research allows for a greater understanding of this. In addition, as first year at university is recognised as a key period for the modification and development of effective social supports (Park et al., 2015; Scarapicchia et al., 2017; Vungkhanching et al., 2017) and the development of social supports outside of the classroom setting (Jun et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2017; Leary & DeRosier, 2012; Maunder, 2018), educators may play a key role in this. Recent research has highlighted the potential of online support mechanisms for the development of social supports and their increased use with first year students (Masserini & Bini, 2021). In line with this finding, the development of online social supports may offer a way to mitigate some of the stressors typically encountered by students during their academic journey and due to their ease of access and attractiveness may be utilised throughout students’ studies. While the current research did not explore the use of such supports specifically, future research is planned for this area, and it may be of particular interest as students have spent significant periods of time engaged accessing supports online during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

In terms of limitations, the current research did not involve an exploration of the socioeconomic status or living situations of the students sampled. Previous research has identified the impact of separation from significant others (Casapulla et al., 2020; Meehan & Howells, 2017; Mamun et al., 2019) and living with peers, sharing similar experiences (Meehan & Howells, 2017; Mishra, 2020) on both stress and social support. Further to this, the measure of social support used in the current study is focused on support perceived to be available from significant others, family and friends, and as such, the current research did not explore social support from academic supports. A further limitation of the current research is that it is a single case study within one university, and as such, the findings might not be generalisable to other universities or students in other years of study or programmes. Previous research has identified that students within certain disciplines can experience higher levels of social support due to the type of teaching and smaller class sizes, such as in nursing (Reeve et al., 2013). While the current research did not directly explore levels of social support within different disciplines, the sample did include students from health and caring disciplines which may have impacted the results. In terms of the experience of stress, as the research was designed to explore the immediate stress experienced by students during the transition to university, the study focused on the experiences during the previous month only and as such did not include stress response to specific high stress situations (Day & Livingstone, 2003). Further research is planned with students at various stages in their studies to identify responses at periods when students may be at higher risk of experiencing stress, such as during high-stake examinations and placements (Voltmer et al., 2012), and with identified scenarios of high-risk experiences to identify further individual differences.

The current research findings provide insight on student experiences as they navigate the important transition to university and the associated increasing academic and social demands they encounter (Leary & DeRosier, 2012). The ability of students to navigate their way and cope with the stress of such a transition has consistently been identified as having important implications for psychosocial wellbeing as well as academic success and as such is important at an individual and a wide spread university level. In terms of implications of this research, a greater understanding of the experience of first year students provides the opportunity to educate staff and students on the issues associated with the transition to university. Normalising wellbeing is recognised as important for all students (Batchelor et al., 2020; Cage et al., 2021; Li et al., 2018a, b), and the current findings provide a platform for educating students regarding issues, such as stress, that are typically encountered during first year, and on the importance of developing a range of effective social supports. In addition to a growing awarness of the impact of academic demands, is a recognition of diversity and gender differenes in the student experience at university (Cox & Naylor, 2018; McCoy et al., 2014; Park et al., 2015). Through understanding the experience of specific groups and individuals, educators may tailor supports to address such needs, and the current research findings can contribute to this area. The findings suggest that female students in particular may require additional supports to manage stress effectively and to develop effective social support networks.

The current findings add to the literature identifying the value of effective social support to cope with stressors as students transition to third-level education (Maunder, 2018; Meehan & Howells, 2017; Scanlon et al., 2020). First year at university is recognised as a unique time for student’s experience of social support and stress, due to separation, individuation and the development of new connections with others. The current research further highlights the potential of developing effective social supports for students (Maymon et al., 2019; Reeve et al., 2013; Scarapicchia, 2017; Vungkhanching et al., 2017), as they meet the challenges associated with this period of transition. As the development of peer relationships and associated social supports will take time to develop as students’ progress through education, a recognition of other forms of social support by educators will ensure that students are accessing social support from the start of their academic journey. The finding that transition to university may be more challenging for females in addition to the gender differences identified in the experience of social support suggests that targeted interventions for female students may be particularly relevant. Extending our understanding of student experience of stress and social supports can help to ensure successful outcomes at an individual and university wide level and enhance the overall experiences of students as they transition to university.

References

Abukari, A. (2010). The dynamics of service of higher education: A comparative study. Compare, 40(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920902831390

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Awang, M. M., Kutty, F. M., & Ahmad, A. R. (2014). Perceived social support and well being: First-year student experience in university. International Education Studies, 7(13), 261–270.

Backović, D. V., Ilić Živojinović, J., Maksimović, J., & Maksimović, M. (2012). Gender differences in academic stress and burnout among medical students in final years of education. Psychiatria Danubina, 24(2), 175–181.

Baltas, A., & Baltas, Z. (2004). Stress and coping ways. Remzi Bookstore.

Barrera, M., Jr. (1986). Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(4), 413–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00922627

Batchelor, R., Pitman, E., Sharpington, A., Stock, M., & Cage, E. (2020). Student perspectives on mental health support and services in the UK. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(4), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1579896

Berwick, D. M., & Finkelstein, J. A. (2010). Preparing medical students for the continual improvement of health and health care: Abraham Flexner and the new “public interest.” Academic Medicine, 85(9), 56-S65. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ead779

Bewick, B., Koutsopoulou, G., Miles, J., Slaa, E., & Barkham, M. (2010). Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they progress through university. Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216643.

Bhandari, P. (2012). Stress and health related quality of life of Nepalese students studying in South Korea: A cross sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10(1), 1–9.

Blair, A. (2017). Understanding first-year students’ transition to university: A pilot study with implications for student engagement, assessment, and feedback. Politics, 37(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395716633904

Brailovskaia, J., Schönfeld, P., Zhang, X. C., Bieda, A., Kochetkov, Y., & Margraf, J. (2018). A cross-cultural study in Germany, Russia, and China: Are resilient and social supported students protected against depression, anxiety, and stress? Psychological Reports, 121(2), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117727745

Brailovskaia, J., Teismann, T., & Margraf, J. (2020). Positive mental health, stressful life events, and suicide ideation. 41, 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000652

Bray, S. R., & Born, H. A. (2004). Transition to university and vigorous physical activity: Implications for health and psychological well-being. Journal of American College Health, 52(4), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.52.4.181-188

Brouwer, J., Jansen, E., Flache, A., & Hofman, A. (2016). The impact of social capital on self-efficacy and study success among first-year university students. Learning and Individual Differences, 52, 109–118, ISSN 1041-6080

Cage, E., Jones, E., Ryan, G., Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2021). Student mental health and transitions into, through and out of university: Student and staff perspectives. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 1–14.https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1875203

Casapulla, S., Rodriguez, J., Nandyal, S., & Chavan, B. (2020). Toward resilience: Medical students Perception of social support. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 120(12), 844–854.

Chao, R. C. L. (2012). Managing perceived stress among college students: The roles of social support and dysfunctional coping. Journal of College Counseling, 15(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00002.x

Charalambous, A. (2019). Social media and health policy. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 6(1), 24.

Charalambous, M. (2020). Variation in transition to university of life science students: Exploring the role of academic and social self-efficacy. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(10), 1419–1432. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1690642

Chavajay, P. (2013). Perceived social support among international students at a US university. Psychological Reports, 112(2), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.2466/17.21.PR0.112.2.667-677

Chen, L., Wang, L., Qiu, X. H., Yang, X. X., Qiao, Z. X., Yang, Y. J., & Liang, Y. (2013). Depression among Chinese university students: Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. PLoS ONE, 8(3), 58379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058379

Cheng, W., Ickes, W., & Verhofstadt, L. (2012). How is family support related to students’ GPA scores? A Longitudinal Study. Higher Education, 64(3), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9501-4

Clara, I. P., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., Murray, L. T., & Torgrudc, L. J. (2003). Confirmatory factor analysis of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in clinically distressed and student samples. Journal of Personality Assessment, 81(3), 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8103_09

Cohen, S. (2004). Social Relationships and Health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676.

Cohen, S., & McKay, G. (1984). Social support, stress, and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In A. Baum, S. E. Taylor, & J. G. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (Vol. IV, pp. 253–267). Erlbaum.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health (pp. 31–68). Sage.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. O. B. I. N. (1983). Perceived stress scale (PSS). Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 24, 285. https://doi.org/10.13072/midss.461

Collings, R., Swanson, V., & Watkins, R. (2016). Peer mentoring during the transition to university: Assessing the usage of a formal scheme within the UK. Studies in Higher Education, 41(11), 1995–2010. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1007939

Collins, S., Coffey, M., & Morris, L. (2010). Social work students: Stress, support and well-being. British Journal of Social Work, 40(3), 963–982. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcn148

Conley, C. S., Shapiro, J. B., Huguenel, B. M., & Kirsch, A. C. (2020). Navigating the college years: Developmental trajectories and gender differences in psychological functioning, cognitive-affective strategies, and social well-being. Emerging Adulthood, 8(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818791603

Cornelius, V., Wood, L., & Lai, J. (2016). Implementation and evaluation of a formal academic-peer-mentoring programme in higher education. Active Learning in Higher Education, 17(3), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787416654796

Cox, S., & Naylor, R. (2018). Intra-university partnerships improve student success in a first-year success and retention outreach initiative. Student Success, 9(3), 51–65.

Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. W. (1990). Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In B. R. Sarason, I. G. Sarason, & G. R. Pierce (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp. 319–366). Wiley.

Day, A. L., & Livingstone, H. A. (2003). Gender differences in perceptions of stressors and utilization of social support among university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 35(2), 73. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087190

Demir, S., Demir, S. G., Bulut, H., & Hisar, F. (2014). Effect of mentoring program on ways of coping with stress and locus of control for nursing students. Asian Nursing Research, 8(4), 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2014.10.004

Denny, E. (2015). Transition from second level and further education to higher education (focused research report no. 6). National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Available from https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/wp-content/uploads/NF-2015-Transition-from-Second-Level-and-Further-Education-to-Higher-Education.pdf

Denovan, A., & Macaskill, A. (2016). Stress and subjective well-being among first year UK undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(2), 505–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9736-y

Evans, W., & Kelly, B. (2004). Pre-registration diploma student nurse stress and coping measures. Nurse Education Today, 24(6), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2004.05.004

Gallop, C. J., & Bastien, N. (2016). Supporting success: Aboriginal students in higher education. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 46(2), 206–224.

Glozah, F. N. (2013). Effects of academic stress and perceived social support on the psychological wellbeing of adolescents in Ghana. Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 2(4), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojmp.2013.24022

Gustems-Carnicer, J., Calderón, C., & Calderón-Garrido, D. (2019). Stress, coping strategies and academic achievement in teacher education students. European Journal of Teacher Education, 42(3), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1576629

Haddadi, P., & Besharat, M. A. (2010). Resilience, vulnerability and mental health. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 639–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.157

Hamdan-Mansour, A. M., & Dawani, H. A. (2008). Social support and stress among university students in Jordan. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6(3), 442–450.

Harikandei, H. (2017). Relationship between perceived social support, mental health and life satisfaction in MSc students of physical education. International Journal of Sports Science, 7(4), 159–162. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.sports.20170704.01

Hartung, F. M., Sproesser, G., & Renner, B. (2015). Being and feeling liked by others: How social inclusion impacts health. Psychology & Health, 30(9), 1103–1115. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2015.1031134

Hausmann, L. R., Schofield, J. W., & Woods, R. L. (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and White first-year college students. Research in Higher Education, 48(7), 803–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-007-9052-9

Heath, J. R., Macfarlane, T. V., & Umar, M. S. (1999). Perceived sources of stress in dental students. Dental Update, 26(3), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.12968/denu.1999.26.3.94

Hefner, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2009). Social support and mental health among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(4), 491–499.

Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039

Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., Adams, C. E., & Glazebrook, C. (2013). A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(3), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015

Jacobson, D. E. (1986). Types and timing of social support. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 27(3), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136745

Jessor, R., Costa, F. M., Krueger, P. M., & Turbin, M. S. (2006). A developmental study of heavy episodic drinking among college students: The role of psychosocial and behavioral protective and risk factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2006.67.86

Jumat, M. R., Chow, P. K. H., Allen, J. C., Lai, S. H., Hwang, N. C., Iqbal, J., Mok, M. U. S., Rapisarda, A., Velkey, J. M., Engle, D. L., & Compton, S. (2020). Grit protects medical students from burnout: A longitudinal study. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02187-1

Jun, W. H., Yang, J., & Lee, E. J. (2018). The mediating effects of social support and a grateful disposition on the relationship between life stress and anger in Korean nursing students. Asian Nursing Research, 12(3), 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2018.08.002

Khallad, Y., & Jabr, F. (2016). Effects of perceived social support and family demands on college students’ mental well-being: A cross cultural investigation. International Journal of Psychology, 51(5), 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12177

Karaca, A., Yildirim, N., Cangur, S., Acikgoz, F., & Akkus, D. (2019). Relationship between mental health of nursing students and coping, self-esteem and social support. Nurse Education Today, 76, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.01.029

Kim, H. J., Hur, W. M., Moon, T. W., & Jun, J. K. (2017). Is all support equal? The moderating effects of supervisor, coworker, and organizational support on the link between emotional labor and job performance. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 20(2), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2016.11.002

Kim, B., Jee, S., Lee, J., An, S., & Lee, S. M. (2018). Relationships between social support and student burnout: A meta-analytic approach. Stress and Health, 34(1), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2771

Kirby, S., Byra, M., Readdy, T., & Wallhead, T. (2015). Effects of spectrum teaching styles on college students’ psychological needs satisfaction and self-determined motivation. European Physical Education Review, 21(4), 521–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15585010

Leary, K. A., & DeRosier, M. E. (2012). Factors promoting positive adaptation and resilience during the transition to college. Psychology, 3(12), 1215. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312A180

Lee, C. Y. S., & Goldstein, S. E. (2016). Loneliness, stress, and social support in young adulthood: Does the source of support matter? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 568–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9

Leese, M. (2010). Bridging the gap: Supporting student transitions into higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 34(2), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098771003695494

Li, J., Han, X., Wang, W., Sun, G., & Cheng, Z. (2018a). How social support influences university students. academic achievement and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of self-esteem. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.016

Li, T., Jiang, S., & Yang, Y. (2018b). Letter by Li et al regarding article, “Particulate matter exposure and stress hormone levels: A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial of air purification.” Circulation, 137(11), 1207–1208. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031385

Liu, C. H., Stevens, C., Wong, S., Yasui, M., & Chen, J. A. (2019). The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among U.S. college students: Implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depression and anxiety, 36(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22830

Lourel, M., Hartmann, A., Closon, C., Mouda, F., & Petric-Tatu, O. (2013). Social support and health: An overview of selected theoretical models for adaptation. Social support, gender and culture, and health benefits, (p 1–20). Nova Science Publishers.

Mamun, M.A., Hossain, M.S., & Griffiths, M.D. (2019). Mental health problems and associated predictors among Bangladeshi students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–15.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00144-8

Mašina, T., Kraljić, V., & Musil, V. (2016). Physical activity and health-promoting lifestyle of first and second year medical students. Pediatrics Today, 12(2), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.5457/p2005-114.152

Masserini, L., & Bini, M. (2021). Does joining social media groups help to reduce students dropout within the first university year? Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 73, 100865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100865

Mattanah, J. F., Brooks, L. J., Brand, B. L., Quimby, J. L., & Ayers, J. F. (2012). A social support intervention and academic achievement in college: Does perceived loneliness mediate the relationship? Journal of College Counseling, 15(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00003.x

Maunder, R. E. (2018). Students’ peer relationships and their contribution to university adjustment: The need to belong in the university community. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(6), 756–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1311996

Maymon, R., Hall, N. C., & Harley, J. M. (2019). Supporting first-year students during the transition to higher education: The importance of quality and source of received support for student well-being. Student Success, 10(3), 64. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v10i3.1407

McCoy, S., & Byrne, D. (2017). Student retention in higher education. In J. Cullinan & D. Flannery (Eds.), Economic insights on higher education policy in Ireland. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48553-9_5

McCoy, S., & Byrne, D. (2017) Student retention in higher education. In Economic insights on higher education policy in Ireland (p. 111–141). Palgrave Macmillan.

McCoy, D. C., Wolf, S., & Godfrey, E. B. (2014). Student motivation for learning in Ghana: Relationships with caregivers’ values toward education, attendance, and academic achievement. School Psychology International, 35(3), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034313508055

McGonagle, A., Freake, H., Zinn, S., Bauerle, T., Winston, J., Lewicki, G., Jehnings, M., Khan-Bureau, D., & Philion, M. (2014). Evaluation of STRONG-CT: A program supporting minority and first-generation US science students. Journal of STEM Education, 15, (1)

Meehan, C., & Howells, K. (2017). What really matters to freshers?: Evaluation of first year student experience of transition into university. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(7), 893–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1323194

Mishra, S. (2020). Social networks, social capital, social support and academic success in higher education: A systematic review with a special focus on ‘underrepresented’ students. Educational Research Review, 29, 100307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100307

Money, J., Nixon, S., Tracy, F., Hennessy, C., Ball, E., & Dinning, T. (2017). Undergraduate student expectations of university in the United Kingdom: What really matters to them? Cogent Education, 4(1), 2331–3186.

Morris, J., III. (2020). Social support among male undergraduates: A systematic review. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 78(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.33225/pec/20.78.235

Naylor, R., Baik, C., & Arkoudis, S. (2018). Identifying attrition risk based on the first year experience. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(2), 328–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1370438

Nelson, I. A. (2019). Starting over on campus or sustaining existing ties? Social capital during college among rural and non-rural college graduates. Qualitative Sociology, 42(1), 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-018-9399-6

O.Leary, S. (2019). Gender and management implications from clearer signposting of employability attributes developed across graduate disciplines. Studies in Higher Education, 1–20.https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1640669

Opoku-Acheampong, A., Kretchy, I. A., Acheampong, F., Afrane, B. A., Ashong, S., Tamakloe, B., & Nyarko, A. K. (2017). Perceived stress and quality of life of pharmacy students in University of Ghana. BMC Research Notes, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2439-6

Othieno, C. J., Okoth, R. O., Peltzer, K., Pengpid, S., & Malla, L. O. (2014). Depression among university students in Kenya: Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.070

Park, K. H., Kim, D. H., Kim, S. K., Yi, Y. H., Jeong, J. H., Chae, J., Hwang, J., & Roh, H. (2015). The relationships between empathy, stress and social support among medical students. International Journal of Medicine and Education, 5(6), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.55e6.0d44

Pluut, H., Curşeu, P. L., & Ilies, R. (2015). Social and study related stressors and resources among university entrants: Effects on well-being and academic performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 262–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.11.018

Polman, R., Borkoles, E., & Nicholls, A. R. (2010). Type D personality, stress, and symptoms of burnout: The influence of avoidance coping and social support. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(3), 681–696. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910709X479069

Poots, A., & Cassidy, T. (2020). Academic expectation, self-compassion, psychological capital, social support and student wellbeing. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101506. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00409-1

Poudel, A., Gurung, B., & Khanal, G. P. (2020). Perceived social support and psychological wellbeing among Nepalese adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem. BMC Psychology, 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00409-1

Reeve, K. L., Shumaker, C. J., Yearwood, E. L., Crowell, N. A., & Riley, J. B. (2013). Perceived stress and social support in undergraduate nursing students’ educational experiences. Nurse Education Today, 33(4), 419–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.11.009

Regehr, C., Clancy, D., & Williams, A. (2013). Interventions to reduce stress in university students: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorder, 15(148), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.026

Santini, Z. I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., Mason, C., & Haro, J. M. (2015). The association between social relationships and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049

Scanlon, M., Leahy, P., Jenkinson, H., & Powell, F. (2020). ‘My biggest fear was whether or not I would make friends’: Working-class students’ reflections on their transition to university in Ireland. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(6), 753–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1597030

Scarapicchia, T. M., Sabiston, C. M., Pila, E., Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P., & Faulkner, G. (2017). A longitudinal investigation of a multidimensional model of social support and physical activity over the first year of university. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 31, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.03.011

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Pieterse, M. E., Drossaert, C. H., Westerhof, G. J., De Graaf, R., Ten Have, M., Walburg, J. A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). What factors are associated with flourishing? Results from a large representative national sample. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1351–1370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9647-3

Soman, S., Bhat, S. M., Latha, K. S., & Praharaj, S. K. (2016). Gender differences in perceived social support and stressful life events in depressed patients. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 26(1), 22–29.

Sosu, E. M., & Pheunpha, P. (2019). Trajectory of university dropout: Investigating the cumulative effect of academic vulnerability and proximity to family support. Frontiers in Education, 4, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00006

Struthers, C. W., Perry, R. P., & Menec, V. H. (2000). An examination of the relationship among academic stress, coping, motivation, and performance in college. Research in Higher Education, 41(5), 581–592.

Sun, S. H., & Zoriah, A. (2015). Assessing stress among undergraduate pharmacy students in University of Malaya. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, 49(2), 99–105.

Tavolacci, M. P., Ladner, J., Grigioni, S., Richard, L., Villet, H., & Dechelotte, P. (2013). Prevalence and association of perceived stress, substance use and behavioral addictions: A cross-sectional study among university students in France, 2009–2011. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-724

Terzi, S. (2008). The relationship between psychological hardiness and perceived social support of university students. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi; Cilt 3 Sayı, 29, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00409-1

Theodore, R., Gollop, M., Tustin, K., Taylor, N., Kiro, C., Taumoepeau, M., Kokaua, J., Hunter, J., & Poulton, R. (2017). Māori University success: What helps and hinders qualification completion. Alternative: An international Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 13(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117700799

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

Tough, H., Siegrist, J., & Fekete, C. (2017). Social relationships, mental health and wellbeing in physical disability: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4308-6

Trepte, S., & Scharkow, M. (2016). Friends and Lifesavers: How social capital andsocial support received in media environments contribute to well-being. In L. Reinecke & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being (pp. 304–316). Routledge.

Tyssen, R., Vaglum, P., Grønvold, N. T., & Ekeberg, Ø. (2001). Factors in medical school that predict postgraduate mental health problems in need of treatment. A nationwide and longitudinal study. Medical Education, 35(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2001.00770.x

Uchino, B. N., Bowen, K., Carlisle, M., & Birmingham, W. (2012). Psychological pathways linking social support to health outcomes: A visit with the “ghosts” of research past, present, and future. Social Science & Medicine, 74(7), 949–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.023

Van der Zanden, P. J., Denessen, E., Cillessen, A. H., & Meijer, P. C. (2018). Domains and predictors of first-year student success: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 23, 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.01.001

Voltmer, E., Kötter, T., & Spahn, C. (2012). Perceived medical school stress and the development of behavior and experience patterns in German medical students. Medical Teacher, 34(10), 840–847. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.706339

Vungkhanching, M., Tonsing, J. C., & Tonsing, K. N. (2017). Psychological distress, coping and perceived social support in social work students. British Journal of Social Work, 47(7), 1999–2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw145

Walton, G. M., Logel, C., Peach, J. M., Spencer, S. J., & Zanna, M. P. (2015). Two brief interventions to mitigate a “chilly climate” transform women’s experience, relationships, and achievement in engineering. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(2), 468.

Warshawski, S., Itzhaki, M., & Barnoy, S. (2018). The associations between peer caring behaviors and social support to nurse students’ caring perceptions. Nurse Education in Practice, 31, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.05.009

Werner-Seidler, A., Afzali, M. H., Chapman, C., Sunderland, M., & Slade, T. (2017). The relationship between social support networks and depression in the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(12), 1463–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1440-7

Wilcox, P., Winn, S., & Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(6), 707–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500340036

Winemiller, D. R., Mitchell, M. E., Sutliff, J., & Cline, D. I. (1993). Measurement strategies in social support: A descriptive review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(5), 638–648.

Wolf, L. A., Perhats, C., Delao, A., & Martinovich, Z. (2017). The effect of reported sleep, perceived fatigue, and sleepiness on cognitive performance in a sample of emergency nurses. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 47(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000435

Yildirim, I., Genctanirim, D., Yalcin, I., & Baydan, Y. (2008). Academic achievement, perfectionism and social support as predictors of test anxiety. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 34(34), 287–296.

Yıldırım, N., Karaca, A., Cangur, S., Acıkgoz, F., & Akkus, D. (2017). The relationship between educational stress, stress coping, self-esteem, social support, and health status among nursing students in Turkey: A structural equation modeling approach. Nurse Education Today, 48, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.09.014

Zamani-Alavijeh, F., Dehkordi, F. R., & Shahry, P. (2017). Perceived social support among students of medical sciences. Electronic Physician, 9(6), 4479. https://doi.org/10.19082/4479

Zhang, M., Zhang, J., Zhang, F., Zhang, L., & Feng, D. (2018). Prevalence of psychological distress and the effects of resilience and perceived social support among Chinese college students: Does gender make a difference? Psychiatry Research, 267, 409–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.038

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Wolf, L., Stidham, A. W., & Ross, R. (2015). Predictors of stress and coping strategies of US accelerated vs. generic Baccalaureate Nursing students: an embedded mixed methods study. Nurse Education Today, 35(1), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.07.005

Wu, D., Yang, T., Rockett, I. R., Yu, L., Peng, S., & Jiang, S. (2021). Uncertainty stress, social capital, and suicidal ideation among Chinese medical students: Findings from a 22 university survey. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(2), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318805820

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted from the Ethics Committee within Technological University Dublin, Blanchardstown for the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McLean, L., Gaul, D. & Penco, R. Perceived Social Support and Stress: a Study of 1st Year Students in Ireland. Int J Ment Health Addiction 21, 2101–2121 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00710-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00710-z