Abstract

Background

Development and validation of Veterans RAND 12-item (VR-12) physical component survey (PCS) has been established among civilian and veteran populations but it has not been examined among anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) patients.

Purposes/Questions

We sought to validate legacy patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) with VR-12 PCS among patients undergoing ACDF procedures.

Methods

A prospectively collected surgical registry was retrospectively evaluated for elective single or multi-level ACDFs performed for degenerative spinal pathologies from January 2014 to August 2019. Exclusion criteria included missing pre-operative surveys and surgery for trauma, metastasis, or infection. Demographic variables, baseline pathologies, and peri-operative variables were collected. A paired t test evaluated the change from the pre-operative score to each post-operative timepoint for VR-12 PCS, the 12-item Short-Form Survey (SF-12) PCS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System physical function (PROMIS-PF), and Neck Disability Index (NDI). Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) achievement was calculated at each timepoint. Correlation was evaluated with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient and time-independent partial correlation.

Results

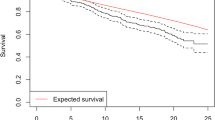

Of the 202 patients who underwent ACDF, 41.1% were female and the average age was 49.5 years. All PROMs had statistically significantly increased from baseline when compared with post-operative timepoints (12 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years). MCID achievement rates increased through 2 years. All timepoints revealed strong VR-12 PCS correlations with SF-12 PCS, PROMIS-PF, and NDI scores.

Conclusion

VR-12 PCS was strongly correlated with the well-validated SF-12 PCS and NDI metrics as well as with the more recent PROMIS-PF. All PROMs demonstrated statistically significant improvement in patients post-operatively. VR-12 PCS is a valid measure of physical function among patients undergoing ACDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Andresen AK, Paulsen RT, Busch F, Isenberg-Jørgensen A, Carreon LY, Andersen MØ. Patient-reported outcomes and patient-reported satisfaction after surgical treatment for cervical radiculopathy. Global Spine J. 2018;8:703–708.

Anon. AAOS File Uploads—NDI. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/uploadedFiles/NDI.pdf. Accessed 6 Apr 2020.

Auffinger B, Lam S, Shen J, Thaci B, Roitberg BZ. Usefulness of minimum clinically important difference for assessing patients with subaxial degenerative cervical spine disease: statistical versus substantial clinical benefit. Acta Neurochir. 2013;155:2345–2355.

Boody BS, Bhatt S, Mazmudar AS, Hsu WK, Rothrock NE, Patel AA. Validation of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) computerized adaptive tests in cervical spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28:268–279.

Carreon LY, Glassman SD, Campbell MJ, Anderson PA. Neck Disability Index, short form-36 physical component summary, and pain scales for neck and arm pain: the minimum clinically important difference and substantial clinical benefit after cervical spine fusion. Spine J. 2010;10:469–474.

Carter Clement R, Bhat SB, Clement ME, Krieg JC. Medicare reimbursement and orthopedic surgery: past, present, and future. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:224–232.

Chow A, Mayer EK, Darzi AW, Athanasiou T. Patient-reported outcome measures: the importance of patient satisfaction in surgery. Surgery. 2009;146:435–443.

Chung AS, Copay AG, Olmscheid N, Campbell D, Walker JB, Chutkan N. Minimum clinically important difference: current trends in the spine literature. Spine. 2017;42:1096–1105.

Cohen J. CHAPTER 4 - Differences between Correlation Coefficients. In: Cohen J, ed. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press; 1977:109–143.

Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009:MR000008.

Egleston BL, Miller SM, Meropol NJ. The impact of misclassification due to survey response fatigue on estimation and identifiability of treatment effects. Stat Med. 2011;30:3560–3572.

Evans JD. Straightforward statistics for the behavioral sciences. Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co; 1996.

Gornet MF, Copay AG, Sorensen KM, Schranck FW. Assessment of health-related quality of life in spine treatment: conversion from SF-36 to VR-12. Spine J. 2018;18:1292–1297.

Haws BE, Khechen B, Bawa MS, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System in spine surgery: a systematic review. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2019;30:405–413.

Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873–880.

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993;2:217–227.

Hung M, Saltzman CL, Voss MW, et al. Responsiveness of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), Neck Disability Index (NDI) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) instruments in patients with spinal disorders. Spine J. 2019;19:34–40.

Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1989;10:407–415.

Jones D, Kazis L, Lee A, Rogers W, Skinner K, Cassar L, Wilson N, Hendricks A. Health status assessments using the Veterans SF-12 and SF-36: methods for evaluating outcomes in the Veterans Health Administration. J Ambul Care Manage. 2001;24:68.

Kazis LE, Lee A, Spiro A 3rd, et al. Measurement comparisons of the medical outcomes study and veterans SF-36 health survey. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;25:43–58.

Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark JA, et al. Improving the response choices on the veterans SF-36 health survey role functioning scales: results from the Veterans Health Study. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27:263–280.

Kazis LE, Ren XS, Lee A, Skinner K, Rogers W, Clark J, Miller DR. Health status in VA patients: results from the Veterans Health Study. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:28–38.

Kazis LE, Selim A, Rogers W, Ren XS, Lee A, Miller DR. Dissemination of methods and results from the Veterans health study: final comments and implications for future monitoring strategies within and outside the Veterans healthcare system. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29:310–319.

Khechen B, Patel DV, Haws BE, et al. Evaluating the concurrent validity of PROMIS physical function in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Clin Spine Surg. 2019;32(10):449–453. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000000786.

Khor S, Lavallee D, Cizik AM, et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for pain and functional outcomes after lumbar spine surgery. JAMA Surgery. 2018;153:634.

Kronzer VL, Jerry MR, Ben Abdallah A, et al. Changes in quality of life after elective surgery: an observational study comparing two measures. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:2093–2102.

Lapin BR, Kinzy TG, Thompson NR, Krishnaney A, Katzan IL. Accuracy of linking VR-12 and PROMIS global health scores in clinical practice. Value Health. 2018;21:1226–1233.

Laucis NC, Hays RD, Bhattacharyya T. Scoring the SF-36 in orthopaedics: a brief guide. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1628–1634.

McGirt MJ, Speroff T, Dittus RS, Harrell FE Jr, Asher AL. The National Neurosurgery Quality and Outcomes Database (N2QOD): general overview and pilot-year project description. Neurosurg Focus. 2013;34:E6.

Moses MJ, Tishelman JC, Stekas N, et al. Comparison of Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System With Neck Disability Index and visual analog scale in patients with neck pain. Spine . 2019;44:E162–E167.

Oglesby M, Fineberg SJ, Patel AA, Pelton MA, Singh K. Epidemiological trends in cervical spine surgery for degenerative diseases between 2002 and 2009. Spine. 2013;38:1226–1232.

Paulino Pereira NR, Janssen SJ, et al. Most efficient questionnaires to measure quality of life, physical function, and pain in patients with metastatic spine disease: a cross-sectional prospective survey study. Spine J. 2017;17:953–961.

Peolsson A, Peolsson M. Predictive factors for long-term outcome of anterior cervical decompression and fusion: a multivariate data analysis. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:406–414.

Purvis TE, Andreou E, Neuman BJ, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Concurrent validity and responsiveness of PROMIS health domains among patients presenting for anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine. 2017;42:E1357–E1365.

Recinos PF, Dunphy CJ, Thompson N, Schuschu J, Urchek JL 3rd, Katzan IL. Patient satisfaction with collection of patient-reported outcome measures in routine care. Adv Ther. 2017;34(2):452–465. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0463-x.

Schalet BD, Rothrock NE, Hays RD, et al. Linking physical and mental health summary scores from the veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) to the PROMIS Global Health Scale. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1524–1530.

Selim AJ, Rogers W, Fleishman JA, et al. Updated U.S. population standard for the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12). Qual Life Res. 2009;18:43–52.

Selim AJ, Rogers W, Qian SX, Brazier J, Kazis LE. A preference-based measure of health: the VR-6D derived from the veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1337–1347.

Steinhaus ME, Iyer S, Lovecchio F, et al. Which NDI domains best predict change in physical function in patients undergoing cervical spine surgery? Spine J. 2019;19:1698–1705.

Vaishnav AS, Gang CH, Iyer S, McAnany S, Albert T, Qureshi SA. Correlation between NDI, PROMIS and SF-12 in cervical spine surgery. Spine J. 2020;20:409–416.

Vernon H, Mior S. The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1991;14:409–415.

Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25:3130–3139.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Lincoln: QualityMetric. 1998.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Nathaniel W. Jenkins, MS, James M. Parrish, MPH, Michael T. Nolte, MD, Nadia M. Hrynewycz, BS, and Thomas S. Brundage, BS, declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Kern Singh, MD, reports personal fees and royalties from Zimmer Biomet, royalties from Stryker, RTI Surgical, and Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, stock ownership from Avaz Surgical LLC, stock ownership and board membership from Vital 5 LLC, personal fees from K2M, non-financial support and board membership from TDi LLC, non-financial support from Minimally Invasive Spine Study Group, Contemporary Spine Surgery, Orthopedics Today, and Vertebral Columns, and grants from Cervical Spine Research Society, outside the submitted work.

Human/Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was waived] from all patients for being included in this study.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Additional information

Level of Evidence: Level III: Retrospective Cohort Study

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jenkins, N.W., Parrish, J.M., Nolte, M.T. et al. Validating the VR-12 Physical Function Instrument After Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion with SF-12, PROMIS, and NDI. HSS Jrnl 16 (Suppl 2), 443–451 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-020-09817-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-020-09817-w