Abstract

Self-regulated learning (SRL) is crucial to students’ learning. SRL is characterized by students taking initiative, showing perseverance and adaptively regulating their learning. Teachers play an essential role in promoting and fostering this process. However, several studies have shown that in primary education explicit instruction of SRL strategies barely takes place. Given the relevance of SRL for learning and preparing students for the knowledge society of the 21st century, it is of crucial importance that teachers in primary education learn how they can improve their students’ SRL. In the present study, we implemented a professional development program (iSELF) in which primary teachers were trained and coached in promoting and fostering their students’ SRL. The extent to which iSELF contributed to teachers’ explicit instruction of SRL strategies was evaluated in a quasi-experimental pre-test-post-test design using video-based classroom observations. Thirty teachers from fourteen different primary schools participated in this study and were assigned to either a control (twelve teachers) or an experimental group (eighteen teachers). Results indicate that in both conditions explicit SRL strategy instruction is rare. However, explicit instruction of SRL strategies is significantly higher in the experimental group on the post-test compared to the control group showing that teachers do benefit from learning about explicit SRL instruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Striking changes in the current society, resulting from rapid technological changes and the exponentially growing amount of information that is available, create a need for alternative approaches to learning. The primary goal of learning has shifted from being able to remember and repeat information, to finding and using it more successfully. Consequently, learning how to regulate one’s learning activities has become “an important survival tool” (Bjork et al., 2013, p. 418). Successful self-regulated learners entertain the skills needed to meet these demands. A distinctive feature of self-regulated learners is that they take initiative, show perseverance and adaptively shape their learning process by employing a combination of metacognitive, cognitive, motivational and behavioral strategies (Boekaerts et al., 2005; Winne, 2011; Zimmerman, 2013). Several review studies have convincingly shown that self-regulated learning (SRL) has a major impact on student’s academic achievement and learning motivation (De Bruijn-Smolders et al., 2016; Dent & Koenka, 2016; Dignath & Büttner, 2008; Donker et al., 2014; Elhusseini et al., 2022; Hattie et al., 1996; Jansen et al., 2019). Therefore, the promotion of SRL increasingly plays a crucial role in formal education.

Research indicates that students can effectively acquire SRL strategies through instruction. For instance, several reviews have shown that students benefit from explicit instruction of SRL strategies (Boekaerts & Corno, 2005; Dignath & Büttner, 2008; Dignath et al., 2008a; Dignath & Veenman, 2021; Hattie et al., 1996; Perry et al., 2004). This means that teachers model the use of SRL strategies and explain when and how these strategies can be used and why executing them contributes to students’ learning (Harris et al., 2013; Schuster et al., 2023; Zohar & Peled, 2008). However, research indicates that teachers fail to effectively teach and support their students’ SRL in this way (Kramarski & Michalsky, 2009; Perry et al., 2004). In his commentary to a special issue in Metacognition and Learning, Greene (2021, p.657) states that there is compelling evidence “that teachers are more like to create learning environments that require or expect students’ SRL activity ability than they are to explicitly instruct the SRL knowledge, skills, or dispositions needed for that ability”. Moreover, observation studies show that teachers in primary and secondary education often do not succeed in explicitly instructing SRL strategies in the classroom (Bolhuis & Voeten, 2001; Dignath-Van Ewijk et al., 2013; Dignath-Van Ewijk, 2016; Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Kistner et al., 2010). In addition, teacher beliefs related to SRL instruction affect the extent to which teachers stimulate SRL in their classrooms (Dignath-Van Ewijk & Van der Werf, 2012; Lawson et al., 2019. In primary education, SRL instruction is remarkably rare, because teachers feel hesitant and lack knowledge on how to advance students’ SRL (Dignath-Van Ewijk & van der Werf, 2012; Heirweg et al., 2022; Perry et al., 2008). Therefore, we developed iSELF – an evidence-informed professional development program (PDP) that focuses on the in-class training of primary teachers in providing explicit SRL instruction (Adigüzel et al., 2023; Askell-Williams et al., 2012; Dignath, 2021; Harris & Graham, 2017; Heaysman & Kramarski, 2022a).

In this study, we investigated the extent to which participating in iSELF contributed to primary teachers’ explicit instruction of SRL strategies. Below, we first conceptualize SRL followed by a description of the design guidelines that underlie our PDP for stimulating elementary teachers’ explicit SRL instruction. Finally, we describe iSELF which is the focus of this study and our evaluation of its effects on the explicit instruction of SRL strategies.

Self-regulated learning

SRL comprises a learner’s planning, monitoring, and evaluation of the learning process, involving learners’ self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that serve to pursue their own goals (Schunk & Zimmerman, 1994). There are multiple conceptualizations of the construct of SRL, however, most researchers agree that SRL refers to an interplay between cognitive, metacognitive, motivational and behavioral processes that are oriented toward goal attainment (Panadero, 2017; Pintrich, 2004; Zimmerman, 2013). Next to these component models that describe the strategies involved in SRL, process models focus on the phases of events that comprise the ideal SRL process. Zimmerman’s (2013) cyclic model of SRL is one of the most predominant process models in research on SRL (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, 2014; Puustinen & Pulkkinen, 2001). This model is grounded in social cognitive theory and describes SRL in terms of three cyclical phases: a forethought phase, a performance phase and a self-reflection phase. The first phase involves orienting on the task, goal setting and strategic planning. During the forethought phase, the learner examines his/her learning goals and motivation, activates prior knowledge, monitors which SRL strategies and tools are necessary to achieve these goals and assesses the time required. In the performance phase, the learner deploys specific SRL strategies that were selected during the forethought phase, monitors the extent to which learning goals are realized, decides whether adjustments in the learning process are needed and acts accordingly. The final self-reflection phase focuses on the evaluation of the learning process. The learner examines to what extent the learning goals have been achieved according to their initial planning, evaluates the effectiveness of the SRL strategies used and judges whether the used tools and support contributed to achieving the learning goals. While these three phases suggest a chronological sequence, there is no assumption that these phases follow a linear sequence. Different phases can take place simultaneously, depending on individual differences of the learner, feedback given during different phases or the change of planning to achieve the learning goal (Zimmerman, 2013). For instance, feedback does not only occur in the final phase but can also be provided in each of the cyclical phases. Likewise, adjusting a plan of approach can also be applied in every phase.

In his seminal paper, Pintrich (2004) combined both component and process models of SRL. This model mostly holds on to the different phases suggested by Zimmerman (2002), but in addition integrates cognitive, metacognitive, motivational and behavioral SRL processes, clearly categorizing the different strategies that are involved during the different phases of SRL. This framework delineates the processes involved in the SRL phases for each of the four different SRL components, adding more detail to how SRL operates in the classroom.

Based on the SRL-strategies discerned in the works of Pintrich (2004) and Zimmerman (2013), reviews of these SRL models (Panadero, 2017; Puustinen & Pulkkinen, 2001), instruments used to assess SRL strategies (Dignath et al., 2008b; Vandevelde et al., 2013) and on practical adaptations that are based on these frameworks (Kostons et al., 2014; Peeters, 2022; Sins et al., 2019), we composed an overview of the most stated cognitive, metacognitive, motivational and behavioral SRL strategies in Table 1. We do not contend that this involves an exhaustive list of SRL strategies and that some researchers mention other strategies or use other terms for similar strategies (Panadero, 2017).

Promoting students’ SRL in the classroom

Review studies show that interventions that effectively contribute to students’ acquiring SRL strategies involve an integrated approach in which cognitive, metacognitive, motivational and behavioral SRL strategies are explicitly instructed (Boekaerts & Corno, 2005; Dignath & Büttner, 2008; Dignath et al., 2008a; Dignath & Veenman, 2021; Graham & Perin, 2007; Hattie et al., 1996; Perry et al., 2004). An integrated approach involves the instruction of SRL strategies that takes place during the teaching of subjects since the use of these strategies is domain specific (Muijs & Bokhove, 2020). This means that SRL teaching should not be decontextualized in individual study lessons that take place separately from the curriculum. An example of an integrated approach is the teaching of the metacognitive strategy of planning in the context of learning to write according to the Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) method developed by Harris and Graham (1992; Graham et al., 1987). SRSD is a well-established, thoroughly validated instructional model used to explicitly teach and model a variety of SRL strategies to elementary, middle, and high school-aged students within the area of writing (Harris & Graham, 2009). In SRSD teachers discuss and model the use of planning for writing a story by employing the mnemonic POW: Pick my ideas, Organize my notes and Write and say more. The advantage of teaching SRL strategies in an integrated manner is that students learn to directly apply these strategies within a specific curricular context. The integration of SRL instruction does, however, not seem to receive priority in primary education (Dignath-Van Ewijk & Van der Werf, 2012; Greene, 2021). This underscores the need to support primary education teachers to integrate SRL instruction into the curriculum of all subjects (Sins et al., 2019; Vrieling-Teunter et al., 2019).

In addition to providing integrated SRL-teaching, explicit instruction of SRL strategies is considered crucial. This means that teachers clearly explain how strategies are applied, under which circumstances these strategies are most effective and what the benefits are of applying them (Dignath & Veenman, 2021; Kistner et al., 2010; Moos & Ringdal, 2012; Muijs & Bokhove, 2020). An approach for explicitly instructing these strategies concerns modelling, which involves students observing their teacher who demonstrates the use of a particular strategy by thinking out loud (Callan et al., 2020; Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007). In contrast to explicit SRL instruction, implicit instruction is provided when teachers do not inform their students about the existence, the conditions, the use and the importance of SRL strategies (Dignath-Van Ewijk & Van der Werf, 2012; Kramarski & Michalsky, 2009; Perry et al., 2004). This has also been labelled as ‘blind training’ (Brown et al., 1981). Based on a scaffolding model of learning, implicit instruction can eventually be an effective way of stimulating students’ strategy use (Callan et al., 2020). But for acquiring SRL strategies “students first have to be trained in self-regulation strategies explicitly to benefit from implicit instruction” (Dignath & Veenman, 2021, p.6).

Explicit instruction of cognitive SRL strategies means that during lessons teachers explicitly address strategies such as organizing, elaborating and problem-solving. In addition, students need to be explicitly instructed about metacognitive strategies used to monitor and regulate cognitive strategies. Concerning the motivational aspect of SRL, Boekaerts and Cascallar (2006) propose that the teacher explicitly initiates and reflects on strategies that encourage students to control their motivation to engage and persist in learning activities. Finally, the teacher can model behavioral strategies by for instance showing students how resource management contributes to learning.

Empirical support for the benefits of explicit instruction of SRL strategies comes from correlational as well as intervention studies. Firstly, based on a systematic review of seventeen classroom observation studies Dignath and Veenman (2021) conclude that there is a positive association between teachers’ explicit instruction of SRL strategies and students’ strategy use. In addition, Kistner et al. (2010) show that explicit SRL instruction is significantly positively related to students’ achievement gains. Secondly, approaches that emphasize and integrate explicit SRL instruction demonstrate positive effects on students’ learning and motivation. For instance, three separate meta-analyses found that SRSD has a strong effect on improving the quality of students’ writing (Graham, 2006; Graham & Harris, 2003; Graham & Perin, 2007). Moreover, Graham and Perin (2007) found that SRSD has the strongest impact on all writing interventions they studied for students in grades four through twelve. Improvements resulting from implementing SRSD were also found with respect to students’ knowledge of writing, approach to writing, their self-efficacy and writing quality (Chen et al., 2022; Harris & McKeown, 2022). Based on SRSD, Rodríguez-Málaga et al. (2021) developed the Cognitive Self-Regulation Instruction (CSRI) program to implement and evaluate strategy-focused explicit instruction that involved teachers modelling writing skills to primary students. Their study showed significant learning gains of 4th-grade students. In addition, the effects of explicit instruction of meta-strategic knowledge (MSK) on learning gains in fifth and eighth-grade students have been studied extensively (Ben David & Zohar, 2009; Zohar & Ben David, 2008; Zohar & Peled, 2008). MSK is defined as general, explicit knowledge about scientific thinking strategies. The results showed significant improvements in students’ strategic and meta-strategic thinking following explicit instruction of MSK that was preserved in a delayed transfer test (cf. Michalsky, 2021a; Zohar & Ben-Ari, 2022). Another study also makes a robust case for incorporating explicit instruction for developing inquiry skills in primary science education. Kuit et al. (2018) found that students receiving explicit instruction scored significantly better on several performance assessments.

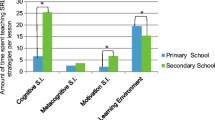

Although students can effectively acquire SRL strategies through explicit instruction and it is associated with significant improvements in students’ learning, several studies show that explicit instruction of SRL strategies hardly takes place in primary and secondary education (Bolhuis & Voeten, 2001; Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Dignath & Veenman, 2021; Hamman et al., 2000; Kistner et al., 2010; Spruce & Bol, 2015). Teachers predominantly provide implicit SRL instruction. This is what Dignath and Veenman (2021) also conclude in their systematic review of seventeen observation studies in primary and secondary education investigating the role of direct and indirect instruction of SRL strategies. It seems that especially in primary education the explicit instruction of SRL strategies is lacking. For instance, Moely et al. (1992) showed that the 69 primary teachers they observed provided suggestions to their students about the use of strategies in only 2% of the cases. Explicit SRL instruction occurred in less than 1% of their observations. In a similar vein, Spruce and Bol (2015) observed ten primary teachers and found that in almost all cases the teachers practiced implicit instruction. Dignath and Büttner (2018) observed the video recordings of twelve third-grade German teachers teaching mathematics and science lessons. The researchers scored two lessons for each teacher using an observation instrument to assess the instruction of SRL. The researchers found zero instances of explicit SRL instruction in their observations of the videos of the elementary teachers. Similar results are obtained for teachers in secondary education. Dignath-Van Ewijk et al. (2013) and Dignath and Büttner (2018) found that only one of the sixteen math teachers they observed spent an average of 2.43 min of his lessons on providing explicit SRL instruction. Hamman et al. (2000) analyzed a total of 33 video recordings of eleven teachers from one high school in the United States and found that only 2% of the instruction segments involved teachers’ SRL instruction. Bolhuis and Voeten (2001) conducted 130 observations in the upper grades of 68 teachers from six Dutch secondary schools. They found that only 5% of the total instruction time teachers are engaged in explicit SRL instruction.

Although teachers acknowledge the importance of promoting SRL strategies in their classes, they rarely provide the explicit instruction needed for students to acquire SRL strategies effectively (Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Veenman, 2011). Moreover, the meta-analyses of Dignath et al. (2008a) show that the effects of approaches for stimulating students’ SRL are more significant if they are executed by researchers instead of teachers who made use of scripted, standard protocols for SRL teaching. Unambiguously, research points to the need for teachers to be trained in explicit instruction of SRL strategies including the necessity to integrate this explicit instruction in a domain-specific way. Therefore, it is key to acquire a PDP to effectively professionalize primary teachers in promoting students’ acquisition of SRL strategies through explicit instruction.

Existing professional development programs in self-regulated learning

Despite differences in SRL PDPs structuring, foci, and practices, research offers support for their overall effectiveness which is mainly manifested in improvements in primary teachers’ performance and learning. For instance, Hilden and Pressley (2007) found that a year-long program in which primary school teachers were trained to explicitly promote SRL, resulted in improvements in both their reading comprehension instruction and in students’ strategy use. Perry and VandeKamp (2000) describe the effects of an approach in which they trained five primary school teachers for fourteen hours each month. During these meetings, the teachers discussed with the researchers how they could best support their students in learning to read and write. They also made lesson plans to experiment with new instructions and strategies for SRL during subsequent lessons that were collectively evaluated. Class observations showed that the approach enabled the teachers to better provide indirect support by offering their students challenging writing and reading tasks, appropriately challenging them and allowing them to choose what they wanted to read or write. In addition, the teachers were also more able to provide explicit strategy instruction by giving knowledge about when and how to use SRL strategies (see also Perry, 1998).

Another case concerns the research of Dignath (2021) who provided a short workshop of eight hours for 33 primary school teachers. This workshop aimed to support teachers with skills for promoting SRL in their classrooms. Teachers were explained what SRL entails and went into more detail about SRL strategies and how they could integrate instruction into their lessons. In addition, teachers developed lesson plans and thought about which materials they could use to apply what they had learned in their classroom. The control group consisted of twelve teachers. Dignath found that the teachers in the experimental group paid significantly more attention to directly supporting students’ strategy use than the teachers in the control group. In addition, a positive effect of the training was visible in the development of the self-efficacy of teachers in the experimental group.

Similar positive results of PDPs for primary teachers in SRL were obtained in more recent studies (Adigüzel et al., 2023; Benick et al., 2021; Heaysman & Kramarski, 2022a; Heirweg et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2023). For instance, a 16-week SRL PDP that focused on training and supervising sixteen teachers to integrate role-modelling strategies into their teaching achieved significant positive changes in their promotion of SRL skills (Adigüzel et al., 2023). In addition, Heirweg et al. (2022) report on a one-year schoolwide PDP consisting of six coaching sessions focused on explicit instruction, modelling desired behavior, and creating a powerful learning environment in primary education. Their PDP was able to produce a significant improvement in primary teachers’ SRL promotion compared to a control group of teachers who did not follow the sessions. In Heaysman and Kramarski’s study (2022a) 76 language teachers participated in either the SRL-AIDE program (Authentic, Interactive, and Dynamic) or in a control program. Teachers participating in the SRL-AIDE program engaged in training activities designed to support their explicit SRL teaching. Results indicated a significant and systematic improvement in the SRL practices of the teachers in the experimental group. In another study, these researchers also found significant gains in students’ metacognition and academic achievement (Heaysman & Kramarski, 2022b). Finally, Lee et al. (2023) report on three studies in which primary school teachers were trained in four teacher workshop sessions to integrate explicit SRL-teaching in their writing, mathematics and reading lessons. Their findings convincingly show that these interventions were highly effective in stimulating their students’ SRL strategy use and learning performance (cf. Benick et al., 2021).

Whereas the implementation of integrated approaches that enact explicit SRL teaching in classrooms has demonstrated positive effects on primary students’ strategy use and academic achievement, training teachers in stimulating their students’ SRL strategies through explicit SRL instruction does not always result in improvements in student learning (Askell-Williams et al., 2012; Dignath, 2021; Perry & VandeKamp, 2000). Therefore, in this study we focused on the direct effects of teachers participating in an evidence-informed PDP on their observable performance with respect to their SRL teaching. At the same time, most existing PDPs are rather extensive in scope and moreover require primary teachers to invest quite some time. Therefore, in the present study we developed a PDP (iSELF) together with primary teachers that can help them to effectively realize explicit and integrated SRL-teaching in the time they have available and in ways they consider to be relevant and useful for enhancing their own educational practices (see also Askell-Williams et al., 2012; Perry et al., 2015).

iSELF: a professional development program for fostering primary teachers’ SRL instruction

The instructional practices of iSELF were based on research delineating effective characteristics of teacher PDPs. For instance, Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) extracted seven characteristics of high-quality PDPs that were based on a comprehensive review of 35 PDPs (cf. Desimone, 2009; Desimone & Garet, 2015; Van Veen et al., 2012). In short, they found that effective PDPs: (1) are content-focused and informed by research-based knowledge on a particular content domain, (2) incorporate active learning, (3) support teacher collaboration, (4) use models and modelling, (5) offer coaching and expert support, (6) stimulate feedback and reflection and (7) are of sustained duration and offer multiple opportunities to engage in learning. As shown in Table 2, iSELF emphasized several of these features in addition to the proposition that teachers are more likely to be involved if they experience that their participation will result in knowledge and skills that contribute to their own development and that of their students (see also Cleary et al., 2022; Heirweg et al., 2022).

iSELF is a PDP aimed at supporting teachers to realize an integrated approach in which the explicit instruction of SRL strategies in their classrooms plays a central role. As such iSELF involves a PDP that incorporates both cognitive as well as situative approaches for SRL capitalizing on findings from research that have demonstrated the positive effects of approaches that enact and integrate explicit SRL teaching (see Dignath, 2021). Firstly, we describe how explicit SRL teaching in an integrated way is materialized in iSELF and how this is translated into teachers’ lesson preparation and implementation. Secondly, we demonstrate the situative approach for SRL describing how teachers were trained using iSELF.

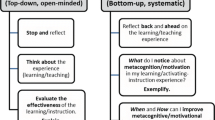

iSELF aims at an integrated instruction of SRL strategies that teachers can directly employ in their lessons. This means that the instruction of SRL strategies needs to be integrated within the context of subject matter content, such as math, reading, history or geography (Dignath & Veenman, 2021; Moos & Ringdal, 2012; Muijs & Bokhove, 2020; Zohar & Ben-Ari, 2022). First, teachers decide on the content they intend to address, including the learning goals for the following lesson. Then, the learning goals are adapted to the specific needs and capabilities of the students. After setting the content and the learning goals, teachers select the SRL strategies they deem necessary for achieving the learning goals. To help teachers in planning their instruction, we developed a flowchart in which they can describe the subject domain, the learning goals and the corresponding selection of SRL strategies that will be addressed in the upcoming lessons (Sins et al., 2019). In addition to integration, iSELF focuses on teaching teachers how to explicitly instruct SRL strategies in the context of the regular curriculum. Thus, the importance of instructing SRL strategies explicitly is stressed (cf. Adigüzel et al., 2023; Askell-Williams et al., 2012; Dignath & Veenman, 2021; Harris et al., 2013; Heaysman & Kramarski, 2022a; Heirweg et al., 2022). This means that iSELF spends a great deal of attention on coaching teachers so that they learn to demonstrate how and when an SRL strategy is used and why its employment contributes to students’ learning processes. The key for teachers is to acknowledge and to know how to explicitly demonstrate the use of SRL strategies, the conditions in which they are employed and what the benefits are of using them. To support teachers to learn how to explicitly instruct SRL strategies, we developed several didactic materials such as a hands-on guidebook, detailed examples of lesson plans, a weekly calendar with tips and a poster visualizing the phases and components of SRL (adapted from Pintrich, 2004) and video clips depicting examples of explicit SRL instruction (Sins et al., 2019).

Exchanging ideas with colleagues, seeking feedback on teaching experiences, and consulting theories of teaching in relation to practical experiences, are important activities in teachers’ professional learning (Bakkenes et al., 2010; Van Veen et al., 2012), and are considered highly supportive for the development of teachers’ knowledge (Van Driel & Berry, 2010). Accordingly, iSELF consists of a plenary training followed by individual and/or group coaching sessions. The plenary training is focused on providing teachers with information on SRL theory and involves comprehensive instruction on the integrated and explicit instruction of SRL strategies. In addition, the use of didactic materials is explained to teachers. To support teachers in optimally implementing the two didactical approaches of integration and explicit instruction (from now on didactics) of iSELF in their lessons, three coaching sessions are subsequently organized during which teachers are supported by a trainer with experience in SRL instruction. Preceding each coaching session, the trainer observes to what extent the teacher provides explicit instruction of SRL during his or her lesson. This lesson observation is followed by a coaching session. In each coaching session teachers – together with their trainer – construct a lesson plan employing the iSELF flowchart and guidebook. In addition, teachers and their trainers intensively reflect on the previous lesson, specifically focusing on the extent to which explicit instruction of SRL strategies is provided. For this, the trainer asks questions and makes references to theoretical notions discussed during the plenary meeting. In dialogue with the teachers, the trainer also defines the relevant goals and learning activities for teachers to provide explicit SRL instruction (see Table 2 for an overview of iSELF).

In the current study, we investigated the extent to which participating in iSELF contributes to an increase in primary teachers’ explicit instruction of SRL strategies, employing a quasi-experimental pre-post-test design using classroom observations and interviews. In this study, we address the following four research questions:

-

1.

What is the effect of participating in iSELF on the extent to which primary teachers spend time on implicit instruction of SRL strategies?

-

2.

What is the effect of participating in iSELF on the extent to which primary teachers spend time on explicit instruction of SRL strategies?

-

3.

Which instances of explicit SRL instruction are found in the classroom of primary teachers?

-

4.

How do primary teachers evaluate iSELF in general, the plenary training and the coaching in light of stimulating students’ SRL in their classrooms?

Method

Design

This study involves a quasi-experimental pre-test-post-test design to establish to which extent teacher participation in iSELF contributes to the increase of explicit SRL instructions. The observational data was collected via video recordings and scored afterwards by two trained coders (second and third author) using the observation instrument ATES (Assessing How Teachers Enhance Self-Regulated Learning) that was originally developed and validated by Dignath et al. (2008b) (see also Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Kistner et al., 2010).

Participants

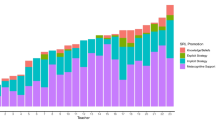

In total 32 primary school teachers in the Netherlands and four primary teachers from a Flemish school volunteered to participate in our study. Six participants were excluded from the sample due to technical failures (inaudible or long fragments in which audio or visual recordings were missing, n = 4) or due to instruction time that was considered too short to make reliable observations (< 25 min, n = 2). In the final dataset, 18 teachers from eight schools formed the experimental group and 12 teachers from six schools formed the control group. Teaching experiences ranged from one to 40 years and 23 of the teachers were female. In addition, five teachers from the experimental group were interviewed (teachers 6, 8, 11, 13 and 31, see Table 2). Four of these teachers were part of the dataset used in our analyses of the classroom observations (teachers 6, 8, 11 and 13), observation data of teacher 31 (from school 5) were not available and only the data that was obtained from our interview was retained. For more background information on the schools, grades and teachers that participated in our study and the subjects they taught during the pre- and post-observation see Table 3.

Most participating teachers taught at a school with an alternative educational pedagogy such as Montessori, Dalton or Jenaplan (Sins et al., 2022). Although there are differences in pedagogy and didactics employed in these schools, the common didactical reform in these schools involves four features: individualizing, activating, contextualizing, and socializing. These schools try to find a better balance between the child and the curriculum by letting pupils work at their own pace and adjusting instruction and assignments to their capabilities and needs (individualizing), by stimulating exploration inside and outside the classroom (activating), by connecting subject matter to pupils’ interests and out-of-school experiences (contextualizing) and by providing opportunities to interact with each other and by stimulating group work (socializing).

Instruments

Observation instrument

We coded the video recordings of teachers’ instructions employing an adapted version of the low-inference coding system of ATES. This observation instrument has been used to quantify teachers’ instructions of specific SRL strategies (Dignath et al., 2008b; Dignath-van Ewijk et al., 2013; Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Kistner et al., 2010). ATES originally consists of two coding systems: a high-inference and a low-inference instrument. The high-inference observation scale focuses on determining the teacher’s design of the learning environment in his or her class. We chose not to use this scale because we were interested in directly observing teachers’ instructions in class. Additionally, the high-inference coding system requires a great deal of interpretation to rate the quality of the instructional environment. The low-inference coding system of ATES allows observers to directly score the quantity and type of specific SRL instructions by coding teachers’ utterances and observable behavior. The coding system of ATES is based on both cyclical and component models of SRL (see also Table 1), classifying strategies into cognitive strategies (elaborating, organizing, problem-solving), metacognitive strategies (planning, monitoring and reflecting), behavioral strategies (resource management and feedback) and motivational strategies (self-motivation and action control).

Elaborating involves instructions where the teacher activates prior knowledge so that students can relate what they already know to new knowledge. Organizing focuses on arranging the learning material in such a way that a certain structure is created which makes it easier to store this information. Problem-solving involves applying procedural strategies that are necessary for information processing. Planning concerns the teacher’s instructions with respect to determining and organizing activities that can be done to achieve a particular goal. Instructions that involve monitoring point to activities that are needed to keep track of the progress of the learning process in relation to the goal. Monitoring involves the evaluation of: the learning process and goals, to which extent the goal has already been attained and/or whether students need to adjust their activities or their planning. Reflecting concerns instructions in which the teacher invites students to think and reason about what happened during their learning process. Instructions that concern resource management are aimed at the deployment of activities to capitalize on the knowledge and skills of others, such as classmates, the teacher, or other resources so that the task can be accomplished. Instructions that are aimed at improving the self-efficacy and mindset of students about the learning task were coded as self-motivation. Action control instructions are intended to prompt and actively motivate students to concentrate and focus on the task at hand. Feedback involves teachers’ substantive and motivational responses to students’ behavior or performance specific to a task.

In addition, for each instruction that was coded, we specified if this was an implicit or explicit instruction. In Table 4 we describe the SRL strategies and decision rules for coding explicit and implicit SRL instructions.

An example of an explicit instruction of the strategy resource management is: “Today I am going to show you how you can manage your resources and how you can apply this yourself in the next assignment”. An illustration of a teacher providing explicit instruction on the strategy planning is: “I am going to demonstrate the strategy planning. I am employing this strategy before I start with my task. Planning means that I first consider what I will do in each step of the task and how much time I will need for each step of the task. I also look at what I need to complete the task. This way I get a better overview of what I am going to do. I’ll soon know exactly what I need to do for the job. And how much time do I need for that.”

We adjusted the observation instrument to fit the specific context of our study. This means that besides translating the observation instrument into Dutch, the descriptions of the coded strategies were made more detailed, decision rules for discerning implicit or explicit SRL instruction were made more specific and we added codes for situations which frequently occurred during the observations such as ‘Class management’ and ‘Silence’. The original ATES consists of nine codes identifying specific SRL instructions; our adjusted instrument involves thirteen codes (see Table 4).

Teacher interview

Five teachers from the experimental group were interviewed face-to-face to obtain their experiences of iSELF and how participating in this PDP may have helped them to enhance their SRL teaching. More specifically, we asked teachers how they evaluated iSELF in general (“What did you learn as a result of participating in iSELF?”), the plenary training (“How effective was the training for you?”) and the coaching sessions (“How relevant were the coaching sessions for you to improve your SRL-teaching?”) in light of stimulating students’ SRL in their classrooms. Additionally, the teachers were asked to provide recommendations for future iSELF training. Each interview lasted about 30 min.

Data analyses

To assess the primary teachers’ SRL instructions we employed classroom observations. We video-recorded two lessons (pre-and post-intervention) of each participating teacher taking place from September 2018 through March 2019, with approximately 28 weeks between the recordings. Teachers were asked to provide a whole class lesson containing a similar subject (e.g., math, spelling or geography) for each observation (see Table 3). The coding system of ATES involves the coding of teachers’ instructions with a time-sampling per minute (see also Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Dignath-van Ewijk et al., 2013; Kistner et al., 2010). This means that for each minute, the specific SRL strategy instruction was coded and observers indicated if the instruction was implicit or explicit. The rationale for one minute being the unit of analysis in ATES is that this enables researchers to capture at least a meaningful part of teachers’ expressions. In addition, employing a longer unit would increase the probability of information loss (see Dignath & Büttner, 2018). Although more strategy instructions could be taught during each 1-minute interval, we eventually coded one strategy instruction and whether the teacher promoted it in an implicit or explicit way based on our general impression of that minute.

Lessons in the Dutch primary school settings do not have fixed lengths, thereby the lengths of the instructions varied with a duration from 26 to 65 min (pre-test: M = 42.81, SD = 9.38; post-test: M = 40.44, SD = 10.90). Because of this variation in duration, we standardized the frequencies of the observations to an interval of 42 min, since the mean duration of all lessons observed was 41.63 with an SD of 10.15. This means that each assigned code was converted into a relatively standardized frequency (assigned code/minutes observed x 42 min).

ATES has been validated in several studies, reporting interrater reliability (IRR) for the specific SRL strategies of Cohen’s Kappa values ranging between κ 0.65 to 0.90 (Dignath et al., 2008b; Dignath-van Ewijk et al., 2013; Dignath & Büttner, 2018) and κ 0.71 – 0.72 (Kistner et al., 2010). In these studies, the IRR regarding the distinction between implicit and explicit instruction could not be calculated due to a lack of power. In an iterative process, we calculated the IRR for the adapted version of ATES. Per iteration two team members coded two observation fragments with a duration of 20 min, in which each minute was coded for the strategy being taught and whether the SRL strategy instruction was implicit or explicit (see Table 4). If the IRR was not satisfactory, the team members discussed the codes and new decision rules were added until an acceptable IRR was reached. Cohen’s Kappa values above 0.70 are considered acceptable (Landis & Koch, 1977; Lombard et al., 2002). The Cohen’s Kappa values of the final IRR calculations was κ 0.75 for the adapted coding system. The IRR for implicit and explicit instruction was very good with 100% agreement between the coders.

Interviews were transcribed and inductively coded into themes for the three interview questions (see Table 6 in the Results section for details). The first and second author started with the open coding of one interview and iteratively discussed the resulting codes (Flick, 2014). After this first round of coding the remaining interviews were qualitatively coded with the established codes by the second author. Newly found codes were again discussed in an iterative session between the first and second authors. Due to the small sample size of the interviews we could not establish and calculate an interrater reliability of the themes found. The standardized procedure that Lombard et al. (2002) provide states that for a reliable interrater reliability a pilot, with a rule of thumb of 30 units, should be coded, before coding the full sample. By reporting the followed coding procedure and being transparent about the lack of interrater reliability for the interview data, we guard the quality of our qualitative data analysis. An overview of the applied categories and codes is presented in the Results section, including quotes from the interviews to supplement our quantitative results.

Procedure

After the first observation (pre-test) teachers were assigned to either the experimental or the control group. Teachers participating in the experiment group were purposefully matched with teachers who did not receive the iSELF training (control group) with respect to grades they taught and their teaching experience. In addition, we matched teachers’ schools with respect to school size, denomination, pedagogy, geographic location, and students’ learning outcomes (see Table 3). The teachers in the experimental group participated in the iSELF program in which they received training and support to realize explicit SRL instruction that they could straightforwardly integrate into their daily teaching in class. iSELF was conducted by the first and third author and a trained coach and started with a half-day plenary training followed by three coaching sessions spanning a period of about five to six months. The plenary training was focused on providing teachers with an in-depth introduction to the didactics of iSELF. The coaching sessions supported teachers to apply the didactics in their lessons and to reflect on their experiences during one-on-one or small group sessions (see Table 2). Teachers in the control group did not receive any specific SRL training.

For the teachers in the experimental group, the video-recordings of their lessons were made before and after they had participated in iSELF. For teachers in the control group, both recordings took place in approximately the same week as for their matched counter partners in the experimental group. Due to organizational reasons, not every teacher taught the same subject during their pre-and post-observation (see Table 3). For this study, we did not exclude these observations because Dutch primary teachers are generalists and provide all the classroom instructions. Also, by excluding data obtained from teachers with different pre-and post-subjects, we would not adhere to the natural classroom context. In iSELF, teachers learn that SRL instructions can be integrated into every lesson, making SRL instructions independent of the subject of the lesson.

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee. Participating teachers signed a written consent form to be part of the research and gave their consent for the video recordings to be used as observational data for our research.

Results

To address our first research question, we first computed means and standard deviations for the instruction of implicit and explicit instruction of SRL strategies of teachers in the experimental and control group (see Table 5). We first investigated the effect of participating in iSELF on teachers’ implicit SRL instruction. For this, we conducted analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the mean post-test proportion scores of teachers’ overall implicit SRL instruction while controlling for potential influences of pre-test scores by using the mean pre-test proportion scores as a covariate (Van Breukelen, 2013). We did not include teaching experience or other variables as covariates in our analyses since this would decrease the power of our findings provided that our sample size was relatively low (Field, 2013). We chose to employ the fewest number of covariates that were most likely to be strongly associated with post-test proportion scores. Assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variances, independence of the covariate and treatment effect and homogeneity of regression slopes were checked. No significant effect was found of participating in iSELF on teachers’ implicit instruction of SRL strategies, F(1, 27) = 1.56, p = .222, partial η2 = 0.05.

For investigating how iSELF contributed to the teacher’s explicit instruction of SRL strategies (second research question) ANCOVA could not be performed since the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were both violated. This was due to the lack of explicit SRL instruction of both groups on the pre-test and of the control group on the post-test. Therefore, we performed a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test on the post-test proportion scores comparing explicit SRL instruction of teachers in the experimental group and the control group. We found that teachers in the experimental group provided significantly more explicit instruction of SRL strategies compared to teachers in the control group, U = 42.00, z = -3.23, p = .004, r = − .59. On average, teachers that participated in iSELF spent significantly more time on explicit instruction of SRL strategies than teachers in the control group. However, no significant differences could be found between groups when taking a closer look at the types of SRL-strategy taught. Out of the eighteen teachers in the experimental group, we found eleven teachers spending time providing explicit SRL instruction with a minimum of 0.66 min and a maximum of 5.83 min per observed lesson. Explicit SRL instruction was observed only for teachers in the experimental condition with respect to the following strategies: planning, resource management, problem-solving, self-motivation and reflecting (see Table 5).

To address our third research question we found several examples of explicit SRL instruction in the post-observation of teachers in the experimental groups. For instance, teacher 3 provided explicit instruction for the strategy planning where she pointed to making a transfer of the use of this strategy to a different subject domain: “We have talked frequently about the strategy planning during math tasks. Today we are going to apply the planning strategy during language tasks. We talked about why a planning is convenient. Who remembers this?” Teacher 7 explicitly explained and illustrated to her students when adjusting a plan is sometimes needed: “Adapting your planning is part of the strategy planning. First, you thought about what you were going to do and if this is not possible anymore, you adjust your plan. For instance: your planning has failed because your buddy was sick and did not have the chance to do his or her part of the task. Now the original planning needs to be adapted because there is a task left. Thinking about when to do this, what there is still left to do for this task as a duo and adjusting the rest of the planning, is all part of the strategy planning”.

Some teachers also explicitly instructed the use of the strategy of resource management. For instance, teacher 11 explicitly demonstrated the use of the strategy resource management in case of a multiplication problem: “You first note what your goal is. For example, if you want to learn the multiplications of six, you first need to think about with whom you could collaborate and then think of which materials you need. I will give an example of applying the strategy ‘resource management’ for the multiplications until 10. First, you get your goal sheet and note your goal, then you go to the material cabinet and take out the practice materials and get back to your table. First, try to do the multiplications. If you need help, you first think of who can help you and then you ask for help.” In addition, teacher 8 explicitly referred to this strategy and states what is needed for its execution: “The learning strategy of today is “resource management”. We need this strategy multiple times a day. [Asks the classroom] Why do we need this strategy? [Children respond] So if you are asking for help and the correct resources, you also need a plan. Instead of asking for help, you can also work with the following approach to select and choose the correct resources. And remember that the strategy of resource management is a strategy that has multiple steps. We will practice every step this week and see what works for you.”

Short instances of explicit instruction of the strategies of problem-solving and self-motivation were found. Teacher 3 first explicitly mentioned the strategy of problem-solving to her students during the language lesson before moving to explain the procedural steps involved in sentence parsing: “Today we are again applying the strategy of planning for sentence parsing. But first, we are going to apply the strategy ‘problem-solving’ because how do we approach sentence parsing?” During the mathematics lesson, teacher 12 explicitly pointed to the strategy of self-motivation in the context of estimated calculation: “Maybe you should motivate yourself. Come on, it will always be useful when you are an adult to know how much the chips and other party groceries costs. Or you could say to yourself ‘Come on, just do it!” Finally, teacher 30 provided explicit SRL instruction with respect to the strategy reflecting during her upper-grade mathematics lesson: “Today we are going to demonstrate a new learning strategy and that is reflecting. Reflecting is a learning strategy you can perform at the end of a learning task. I use this strategy for instance to eventually think about what I can do differently a next time.”

In the interviews we conducted to address our fourth research question, several themes were reflected within the three interview questions (see Table 6). The responses regarding iSELF in general were coded and clustered into the following categories: effect (on teachers and students), gains (material and support) and preconditions (school culture and practice implementation). For the plenary training and coaching sessions, teachers mentioned what the added value of the iSELF program was. The teachers also provided recommendations to further improve iSELF and the sub-components of the program.

In general, the interviewed teachers indicated that iSELF affected them in making them aware of the importance of providing explicit instruction on SRL strategies (code: effect on teachers). For instance, teacher 11 explained “that explicit instruction means that explicitly describe what you do to the children. Like: look, I’m really going to give instructions now, and then I’m going to come to you to give you feedback. To name that. Because you do so much, actually you do all those things as a teacher, but you don’t name them. And that is what iSELF had taught me.” Teacher 31 indicated that “iSELF helped to structure my instruction and to really consciously teach strategies to children without assuming that they will learn, eh, is a great help. That awareness for myself too, how I can consciously apply it, learn it, continue to use it, visualize it, I found that to be a very great added value.” In addition, teachers mentioned an effect on their students (code: effect on students). For instance, teacher 31 indicated that because of explicitly instructing SRL strategies her “students seemed to have become more aware of the steps they can undertake themselves”. Also, teachers valued the benefits of employing the practical materials offered in iSELF (code: practice materials; see Table 6). With respect to preconditions, teachers stated that iSELF as an approach needs to be embedded in the whole school (code: school culture). For instance, teacher 13 states that she would have liked creating a community with colleagues so that they “can come together every month and share what we have done”.

Although the interviewed teachers were positive about the perceived impact of iSELF, a common critical aspect of explicit instruction of SRL strategies, was the challenge of actually implementing it in practice (code: practice implementation). For instance, teacher 8 explained that it took her some effort “in the start-up, yes mainly because it was too much… a lot of people find that difficult in the beginning. But I have now found that out yes, that really ensures that you take a critical look at yourself for once.” Teacher 13 mentioned that explicit SRL teaching “is not yet, how should I say, a fixed part or routine in my teaching to start using those learning strategies. That is to say yes, but it is not always thought through.”

With respect to the plenary training and the coaching sessions the interviewed teachers mentioned added values of iSELF (code: added value). For instance, teacher 13 was very positive about iSELF stating that it “was one of the most instructive professional development programs I have participated in”. In addition, teachers valued the materials we offered them to support their SRL teaching. For instance, teacher 8 mentioned that she used the weekly calendar with tips which helped her to “think more consciously on how I teach and what I take into account”. Teachers also mentioned the added value of the coaching sessions especially appreciating the feedback of the coach (code: added value). For instance, teacher 31 stated that “it was easy to communicate, I could quickly ask something and contact my coach which I found very pleasant” (see also Table 6).

Finally, teachers provided several recommendations to improve iSELF in general, our plenary training and the coaching sessions (codes: recommendations; see Table 6). Suggestions that were provided concerned providing more concrete examples, materials and coaching sessions and setting up a learning community in school to keep SRL teaching on the agenda in schools. For instance, teacher 6 that “I must say that the training sessions we had went very quickly, that some colleagues could not keep up. So, I also sat down with our coach about that a few times, like, can we approach this differently, I actually get more than half of the colleagues, this has to be different. It went very well and eh… I do notice that, but I don’t know if that is the case everywhere or if it is typical iSELF, you have to keep naming a lot what you do in class, you also have to do it with colleagues, otherwise it will ebb away”.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated in a quasi-experimental pre- and post-test design whether a PDP designed for teachers working in primary education (iSELF) was effective in promoting explicit instruction of SRL strategies. Results show that in general teachers participating in iSELF spent significantly more time providing explicit SRL instruction compared to teachers in the control group. We found no significant differences between the two groups with respect to implicit SRL instruction.

Our results point to two general conclusions. Firstly, in our study, we found that teachers hardly spend time on explicit instruction of SRL strategies. In the pre-tests of both groups and in the post-test of the control group we virtually found no evidence of explicit SRL teaching. These results corroborate the findings of other primary classroom observation studies (Bolhuis & Voeten, 2001; Dignath-Van Ewijk et al., 2103; Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Dignath & Veenman, 2021; Hamman et al., 2000; Michalsky & Schechter, 2013; Moely et al., 1992; Spruce & Bol, 2015; Van Beek, 2015). The relative absence of explicit SRL strategy instruction is problematic because of the apparent link between students’ use of SRL strategies and their academic achievement. For instance, Dignath-Van Ewijk et al. (2013) and Kistner et al. (2010) found significant positive relationships between explicit SRL instruction during mathematic lessons and students’ use of SRL strategies and their learning outcomes respectively. We should, however, note that these studies were conducted in secondary education. Similar correlational studies in primary education are currently lacking.

Next to this evidence, several approaches for realizing integrated explicit instruction of SRL in both primary and secondary schools have been found to contribute significantly to students’ learning and performance. And it becomes apparent that the provision of explicit instruction of SRL strategies explains to a large extent the effectiveness of these approaches. For instance, Zohar and Peled (2008) conclude that “it was precisely the explicit teaching of metastrategic knowledge that triggered the development of thinking for students in the experimental group” (p. 351, see also Zohar & Ben David, 2008). The researchers saw significant progress immediately after the students had received explicit instruction from MSK. The researchers, therefore, conclude that students do not automatically ‘pick up’ the strategies they need for inquiry-based learning, and point the necessity for teachers to teach them explicitly. Similarly, the meta-analysis of Graham et al. (2013) showed that explicit instruction explained much of the success of SRSD. They found five studies that investigated the effects of SRSD, with or without explicit instruction. The added value of explicit instruction within SRSD was 0.48. The researchers, therefore, concluded that explicit strategy instruction is important for the success of the SRSD approach (see also Harris & Graham, 2017; Rodríguez-Málaga et al, 2021). Finally, Schunk et al. (2022) found substantial effects in third-grade students after explicit teaching of SRL strategies. During a concise SRL training, the pupils learned about the what, when, why and how of setting and pursuing goals and overcoming obstacles. After this intervention, students scored significantly better on a reading test than students in a control group, who received no training. Even a year after they had completed the training, the reading skills of the students in the experimental group were still significantly higher compared to students in the control group. Moreover, three years later these pupils even received a significantly higher provisional secondary school recommendation. Intervening at a young age is thus helpful. Correspondingly, Skibbe et al. (2019) convincingly showed that children who demonstrate a high degree of early development in SRL, score better on language skills and literacy when they are older. These researchers found a large and long-lasting benefit for students who developed SRL strategies earlier.

The second conclusion that emerged from our findings is that even after having received extensive training, teachers in general refrain from providing explicit SRL instruction. Of the total eighteen teachers in our experimental condition, eleven teachers manifested explicit teaching of SRL strategies in about 3.5% of the observed instances in the post-test. In addition, the interviewed teachers indicated that although iSELF helped them and their students to become more aware of the necessity of explicit SRL instruction, it takes time and effort to implement and realize this in their planned lessons. Similar results were obtained by Askell-Williams et al. (2012) who developed learning protocols for secondary teachers to embed explicit SRL strategy instruction into their regular lessons. These protocols consisted of four components that help teachers to assist their students in (1) selecting the key ideas of the lesson, (2) using prior knowledge, (3) organizing the information presented so that students can remember it, and (4) checking whether students have understood the content of the lesson. The results showed that, in general, students of teachers who worked with the learning protocols showed little progress in the use of cognitive and metacognitive strategies. Askell-Williams et al. (2012) concluded that these disappointing results may be related to teachers perceiving the learning protocols as “researcher-driven ‘add-ons’” that “are likely to be dropped when time pressures, costs, or skill limitations make their maintenance difficult” (p. 433). In line with this, greater effects are found when SRL interventions are carried out by researchers than when they are implemented by teachers (Dignath, 2021; Dignath & Büttner, 2008; Dignath et al., 2008a; Schuster et al., 2020). According to Dignath et al. (2008a), this is “an alarming result” (p. 256) since educational research should eventually help to equip teachers to improve their SRL teaching.

Based on these outcomes Askell-Williams et al. (2012) developed guidelines for effectively integrating SRL interventions into the classroom, such as: making an explicit connection between theory and practice, helping teachers to learn more about the process of SRL, making sure that the intervention is perceived by teachers as immediately applicable and relevant to their practice, creating interventions that take little time and effort to carry out, preferably as a plug-in for the regular lesson and designing interventions where researchers work collaboratively with school leaders and teachers (see also Adigüzel et al., 2023; Gore et al., 2017; Perry et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, considering and providing training in explicit SRL teaching seems to sort of effect. Although the effect is small, we found a significant difference with a control group who did not receive training. In addition, in our interviews teachers indicated that iSELF helped them to become more mindful of the significance of explicit SRL-instruction which is a meaningful finding considering the apparent difficulties of primary teachers to even notice explicit SRL teaching actions (Michalsky, 2021b). In addition, other studies corroborate our findings showing that even relatively short PDPs may positively impact SRL-teaching (Askell-Williams et al., 2012; Benick et al., 2021; Dignath, 2021; Heirweg et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2023). These results are encouraging provided that changing teachers’ practices and routines has been found challenging in other studies (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

Limitations and future directions

To gain more insight into the added value of iSELF on SRL teaching and learning in primary schools, more research is needed, taking into account three limitations of the present study.

Firstly, to provide a more reliable insight into the effectiveness of iSELF, more teachers should be involved in a quasi-experimental design guaranteeing that same subjects are taught during pre- and post-observations. For the present study, we chose to focus on a relatively small group of teachers because we were faced with the practical challenge of collecting and analyzing a large amount of data in different schools (i.e. observations pre- and post and administering interviews) as well as implementing iSELF in the experimental group (i.e. plenary training followed by individual and/or group coaching sessions on three separate occasions). Thus, it should be noted that the results of this study cannot be generalized to all teachers working in primary education. An additional difficulty was that six teachers in the experimental condition and three teachers in the control group did not teach the same subject during the pre-and post-observation (see Table 3). In the natural classroom setting of our study this showed to be challenging to organize. This may have resulted in potential differences in teachers’ SRL teaching between both observation moments that may relate to a different subject being taught. Although this is not an ideal experimental setup and should be modified in future research, in our analyses of the observations we focused on the extent to which teachers provided implicit and explicit SRL instruction regardless of the subject being taught. This may seem at odds with iSELF in which teachers were trained and coached to integrate their explicit SRL teaching in a particular subject domain. However, observing the occurrence of implicit or explicit SRL teaching is not dependent on the subject domain (see Table 4). Nevertheless, it remains an empirical issue to investigate to which extent teachers’ teaching SRL strategies implicitly or explicitly is reliant on the subject domain.

Secondly, we employed the ATES observation scheme in which a distinction is made between either implicit or explicit instruction of SRL strategies. We noticed that in some cases this division proved to be somewhat strict, leaving out in-between instances of SRL instruction in which teachers for instance motivated their students to use a strategy or in which they provided some information about an SRL strategy. Also, a teacher can have students practice various strategies for processing information while informing them that this will help them achieve their goals. In their seminal article Brown et al. (1981) named these types of instruction ‘informed instruction’. In the present study, we scored these instances as ‘implicit’ SRL instruction. We advocate that in future research we should take a more nuanced view of classroom observations, also including informed instruction as an intermediate category between implicit SRL instruction on the one hand and explicit SRL instruction on the other.

Finally, to investigate the extent to which explicit SRL teaching relates to students’ use of SRL strategies and their learning performance, we need to also include student data (cf. Dignath & Veenman, 2021; Kistner et al., 2010). This allows us to examine the effectiveness of iSELF on the level of student learning and to gain insight into the relationship between explicit SRL teaching and students’ SRL and academic achievement. It is important to examine whether this will also be the case with the use of iSELF and what elements might then ensure that student-level effects do occur.

In our study, we found that participating in iSELF contributed to achieving its aim, namely stimulating explicit teaching of SRL strategies in primary schools. Based on our observations we can conclude that teachers who participated in iSELF spend significantly more time on explicit SRL teaching during their lessons. In addition, teachers indicated that they become more aware of the need to assist their students by providing explicit instruction on SRL strategies. Nevertheless, integrating explicit SRL teaching in daily practice that is long-lasting, remains a challenge for teachers that needs to be taken seriously into account in future research.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The data for this research are confidential and have not been deposited in a public repository but are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Adıgüzel, T., Aşık, G., Bulut, M. A., Kaya, M. H., & Özel, S. (2023). Teaching self-regulation through role modeling in K-12. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1105466. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1105466

Askell-Williams, H., Lawson, M. J., & Skrzypiec, G. (2012). Scaffolding cognitive and metacognitive strategy instruction in regular class lessons. Instructional Science, 40(2), 413–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9182-5

Bakkenes, I., Vermunt, J. D., & Wubbels, T. (2010). Teacher learning in the context of educational innovation: Learning activities and learning outcomes of experienced teachers. Learning and Instruction, 20(6), 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.09.001

Ben David, A., & Zohar, A. (2009). Contribution of meta-strategic knowledge to scientific inquiry learning. International Journal of Science Education, 31(12), 1657–1682. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690802162762

Benick, M., Dörrenbächer-Ulrich, L., Weißenfels, M., & Perels, F. (2021). Fostering self-regulated learning in primary school students: Can additional teacher training enhance the effectiveness of an intervention? Psychology Learning & Teaching, 20(3), 324–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/14757257211013638

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

Boekaerts, M., & Cascallar, E. (2006). How far have we moved toward the integration of theory and practice in self-regulation. Educational Psychology Review, 18(3), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9013-4

Boekaerts, M., & Corno, L. (2005). Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54(2), 199–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00205.x

Boekaerts, M., Maes, S., & Karoly, P. (2005). Self-regulation across domains of applied-psychology: Is there an emerging consensus? Applied Psychology, 54(2), 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00201.x

Bolhuis, S., & Voeten, M. J. M. (2001). Toward self-directed learning in secondary schools: What do teachers do? Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00034-8

Brown, A. L., Campione, J. C., & Day, J. D. (1981). Learning to learn: On training students to learn from texts. Educational Researcher, 10(2), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1174401

Callan, G. L., Longhurst, D., Ariotti, A., & Bundock, K. (2020). Settings, exchanges, and events: The SEE framework of selfregulated learning supportive practices. Psychology in the Schools, 58(5), 773–788. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22468

Chen, J., Zhang, L. J., & Parr, J. M. (2022). Improving EFL students’ text revision with the Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) model. Metacognition and Learning, 17, 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-021-09280-w

Cleary, T. J., Kitsantas, A., Peters-Burton, E., Lui, A., McLeod, K., Slemp, J., & Zhang, X. (2022). Professional development in self-regulated learning: Shifts and variations in teacher outcomes and approaches to implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 111, 103619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103619

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute.

De Bruijn-Smolders, M., Timmers, C. F., Gawke, J. C. L., Schoonman, W., & Born, M. P. (2016). Effective self-regulatory processes in higher education: Research findings and future directions. A systematic review. Higher Education, 41(1), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.915302

Dent, A. L., & Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28(3), 425–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x08331140

Desimone, L. M., & Garet, M. S. (2015). Best practices in teachers’ professional development in the United States. Psychology, Society & Education, 7(3), 252–163. https://doi.org/10.25115/psye.v7i3.515

Dignath, C. (2021). For unto every one that hath shall be given: Teachers’ competence profiles regarding the promotion of self-regulated learning moderate the effectiveness of short-term teacher training. Metacognition and Learning, 16, 555–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-021-09271-x

Dignath, C., & Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students: A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary level. Metacognition and Learning, 3(3), 231–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-008-9029-x

Dignath, C., & Büttner, G. (2018). Teachers’ direct and indirect promotion of self-regulated learning in primary and secondary school mathematics classes – insights from video-based classroom observations and teacher interviews. Metacognition and Learning, 13(2), 127–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-018-9181-x

Dignath, C., & Veenman, M. V. J. (2021). The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning - evidence from classroom observation studies. Educational Psychology Review, 33(2), 489–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09534-0

Dignath, C., Buettner, G., & Langfeldt, H. P. (2008a). How can primary school students learn self-regulated learning strategies most effectively? A meta-analysis on self-regulation training programmes. Educational Research Review, 3(2), 101–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2008.02.003

Dignath, C., Büttner, G., & Veenman, M. (2008b). Assessing the instruction of self-regulated learning in real classroom settings. Manual for Coding Procedures. Goethe University Frankfurt.

Dignath-Van Ewijk, C. (2016). Which components of teacher competence determine whether teachers enhance self-regulated learning? Predicting teachers’ self-reported promotion of self-regulated learning by means of teacher beliefs, knowledge, and self-efficacy. Frontline Learning Research, 4(5), 83–105. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v4i5.247

Dignath-van Ewijk, C., & Van der Werf, G. (2012). What teachers think about self-regulated learning: Investigating teacher beliefs and teacher behavior of enhancing students’ self-regulation. Education Research International, 2012, 741713. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/741713

Dignath-van Ewijk, C., Dickhäuser, O., & Büttner, G. (2013). Assessing how teachers enhance self-regulated learning: A multiperspective approach. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 12(3), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.12.3.338

Donker, A. S., De Boer, H., Kostons, D., Dignath-van Ewijk, C. C., & Van der Werf, M. P. C. (2014). Effectiveness of learning strategy instruction on academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 11, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.11.002

Elhusseini, S. A., Tischner, C. M., Aspiranti, K. B., & Fedewa, A. L. (2022). A quantitative review of the effects of self-regulation interventions on primary and secondary student academic achievement. Metacognition and Learning, 17, 1117–1139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-022-093110

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage.

Flick, U. (2014). An instruction to qualitative research. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Gore, J., Lloyd, A., Smith, M., Bowe, J., Ellis, H., & Lubans, D. (2017). Effects of professional development on the quality of teaching: Results from a randomised controlled trial of quality teaching rounds. Teaching and Teacher Education, 68, 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.007

Graham, S. (2006). Strategy instruction and the teaching of writing. In C. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 187–207). Guilford.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2003). Students with learning disabilities and the process of writing: A meta-analysis of SRSD studies. In L. Swanson, K. R. Harris, & S. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of research on learning disabilities (pp. 323–344). Guilford Press.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Sawyer, R. (1987). Composition instruction with learning disabled students: Self-instructional strategy training. Focus on Exceptional Children, 20, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.353

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & McKeown, D. (2013). The writing of students with LD and a meta-analysis of SRSD writing intervention studies: Redux. In L. Swanson, K. R. Harris, & S. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of Learning Disabilities (2nd ed., pp. 405–438). Guilford Press.

Greene, J. A. (2021). Teacher support for metacognition and self-regulated learning: A compelling story and a prototypical model. Metacognition and Learning, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-021-09283-7

Hamman, D., Berthelot, J., Saia, J., & Crowley, E. (2000). Teachers’ coaching of learning and its relation to students’ strategic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(2), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.342

Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (1992). Helping young writers master the craft: Strategy instruction and self-regulation in the writing process. Brookline Books.

Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (2009). Self-regulated strategy development in writing: Premises, evolution, and the future. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 6, 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1348/978185409X422542

Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (2017). Self-regulated strategy development: Theoretical bases, critical instructional elements, and future research. In R. Fidalgo, K. R. Harris, & M. Braaksma (Eds.), Design principles for teaching effective writing: Theoretical and empirical grounded principles (pp. 119–151). Brill.

Harris, K. R., & McKeown, D. (2022). Overcoming barriers and paradigm wars: Powerful evidence-based writing instruction. Theory into Practice, 61(4), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2022.2107334