Abstract

This study reassesses the impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by examining various economic linkages between China and other economies. An extensive review of the literature reveals that empirical studies in this field seldom account for the possibility that the BRI might itself be a product, rather than a cause, of connections between China and the world. Based on statistical analyses of data from 163 countries between 1999 and 2017 and mini-case studies on Italy and Hungary, this study finds that the scope and coverage of the BRI are determined by China’s pre-existing connections with other economies. The actual impact of the BRI on various economic outcomes, with the partial exception of Chinese investments flowing to formal participants, is limited when pre-BRI trends are accounted for. In addition, given the encompassing nature of the BRI framework, the concern that the BRI is autocracy-exporting or corruption-inducing appears to be exaggerated. The study thus calls for a more nuanced consideration of the actual impact of the BRI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (formerly known as One Belt One Road) is perhaps one of the most debated topics in the international community in recent decades due to its ambitious scope, its potential implications for the world, and the controversies related to it. Originating in 2013 as the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road, as conceived by President Xi Jinping, the BRI quickly escalated in scale. It currently encompasses over a hundred countries connected by six “economic corridors” and involves enormous amounts of resources (estimated at $8 trillionFootnote 1). Against the background of China’s rise as an economic and political power, a project of such a scale is bound to divide opinions [59]. These opinions range from those of idealists (the BRI promotes cooperation, harmony, and mutual benefits) to those of realists (the BRI is a bid for global hegemony and a counterbalance to the US strategy of containment) [5, 6, 48] and pessimists (the BRI is self-defeating due to its risks and costs) [40].

Interpretations of the BRI from an economic perspective have tended to portray its underlying rationale as a solution to China’s economic concerns (export for productivity; the need to secure strategic resources) [34, 45] that has limited implications for the regional and global order [2, 13, 52]. In contrast, interpretations from a political–economic perspective have suggested that economic connections and capacity naturally bring about political influence [12]. The “beneficiaries” of the BRI may acknowledge or even endorse China’s leadership, rhetorically echoing the official aim of the BRI to build a “community of shared destiny” [16, 48], however, see [27]. Yet others have viewed the BRI as an outright political project, focusing on how it is proactively used to promote China’s soft power and ideas and challenge the US-led international order [41, 58, 60], for a review, see [30].

To better understand the nature of the BRI, we must accurately assess its actual impact. This study contributes to the empirical discussion on the impact of the BRI. As discussed in the next section, despite a surge in empirical studies on the BRI, no consensus on its impact has yet been reached. Few of these studies have adopted a comparative approach and produced generalizable findings. More importantly, those comparative studies that have resulted in some generalizable findings have not appropriately modeled the nature of the relationship between the BRI and different outcomes, as discussed next, leading to potential biases in their findings. In this study, we examine three key research questions. First, does a country’s participation in the BRI depend on its prior connections with China? Although it is obvious that it should (and much of the literature has discussed the BRI from the international relations perspective), empirical research on the BRI has seldom accounted for this factor. Second, what is the BRI’s true impact, over and above that of the trends of development prior to the BRI? Finally, do the patterns of linkages between a country and China change according to its involvement in the BRI? These questions are assessed through a quantitative analysis of data from 163 countries between 1999 and 2017, and supplemented by mini-case studies on Italy and Hungary.

Although this study focuses on the BRI as a case that has significant potential implications, our findings are also relevant to at least three other branches of comparative studies. First, regarding the formality and purposes of establishing political organizations (e.g., [4, 42, 50], our arguments suggest that the BRI could be a political end, rather than a political means, for China, and that its establishment might be shaped by existing international dynamics rather than vice versa. Second, our results complement the debate on how foreign economic flows and participation in international organizations affect host countries (e.g., [1, 8, 11]. Finally, although this is not the focus of the study, we contribute evidence on the trends and determinants of investments in and bilateral trade flows with China.

The BRI: A Systematic Review of Prior Studies and Their Limitations

The key concern for most countries regarding joining the BRI is its impact on them as a host. As autocracies have an interest in supporting similar regimes elsewhere, scholars have debated whether economic engagement with China enhances an autocratic regime’s survival [3, 9]. Such a perspective has often been supported by findings suggesting that the influx of Chinese capital is detrimental to good governance (e.g., [51] or promotes questionable practices such as bribery and political intervention.Footnote 2 The BRI has also been alleged by some to be a “debt-trap,” with its projects being seen as financially unsustainable, causing a host of difficulties in the repayment of debt and enabling the seizure of strategic assets by the Chinese (e.g., [33]. Several countries (e.g., Sri Lanka) have suspended or scaled down major BRI projects as the underlying economic risks have become apparent [36]. Because it has often focused on large-scale projects in unstable regions, the BRI has also been linked to environmental degradation, forced displacement, and land-grabbing, provoking local socio-political unrest [53, 61]. Although one branch of the literature argues, conversely, that host countries have substantial agency in controlling Chinese investments to suit their own objectives [15], this argument does not preclude the fact that the BRI may also have adverse political and economic effects overall.

Perhaps surprisingly, despite the abovementioned outcomes purportedly associated with the BRI, its impact has often been assumed rather than empirically established (e.g., [24, 57]. Much of the literature has consisted of single case studies examining the motivation for the BRI or the details of specific projects, resulting in findings with limited generalizability [17, 29, 37, 38]. To substantiate this claim, we performed a systematic and exhaustive review of the BRI literature following a standard review methodology [25], the details of which are provided in the Appendix. In brief, out of 1,027 articles, books, and chapters related to the BRI that were obtained from our search, only a small proportion were related to the political or economic impact of the BRI and Chinese investments. The studies that were excluded either focused on other topics (e.g., environment or business) or on the determinants of the BRI. Of the 99 studies that remained, only 29 were global and general in scope, with the rest being regional or case studies.

This collection of empirical studies provides important insights into the overall effects of the BRI. For example, to examine the impact of the BRI, Blanchard [7] examined various types of economic linkages between China and other countries from 2013 onward,Hurley et al. [33] focused on the changing debt levels of participating economies from 2015 to 2018. However, for reasons that are discussed subsequently, a critical limitation of this approach is, paradoxically, its emphasis on the inception of the BRI, i.e., what happened after its announcement in 2013. An exception is the study by Du and Zhang [24], who provided comprehensive qualitative trends of Chinese overseas investments from 2005 to 2015 supplemented by quantitative analysis of data from 2011 to 2015 (in which they compared the changes between the two years before and the two years after the BRI’s announcement).

Although the empirical literature has constituted a definitive improvement, virtually all of the studies that we reviewed (case studies and comparative studies) have neglected a critical aspect of the BRI policy: a country’s engagement in the BRI is not randomly assigned but politically determined. Although case studies may have considered changes leading up to the BRI, they have seldom recognized the implications of these changes for their analysis. In the jargon of research methodology, the process is endogenous, and participation in the BRI is highly likely to be “self-selected.” There are two ways in which this phenomenon may occur. The first is reverse causality: it may not be the case that countries participating in the BRI are more predisposed to Chinese influence than other countries due to their participation; rather, it may be that countries that are friendly toward China are more likely to join the BRI. Given the nature of the BRI, each country’s decision regarding whether and in what capacity to join should be considered to be far from random as it would inevitably be influenced by existing ties with China. For example, the top five BRI participants in terms of the proportion of investment received are Russia, Kazakhstan, Thailand, Pakistan, and Indonesia [31], all of which had close ties with China prior to joining the BRI.

Conversely, other regional powers (Australia, India, and Japan) are reportedly wary of China’s expansionist geo-political intentions [45]. Many BRI routes circumvent areas of traditional American influence irrespective of commercial prospects [46]. Traditional US influence might also condition the level of a country’s participation in the BRI [39]. These a priori factors arguably determine a country’s participation in the BRI, implying that any supposedly posterior effects may in fact be endogenous. Although this logic might seem obvious, studies have frequently neglected the fact that it confounds a straightforward estimation of the BRI’s overall effect.

Second, even after accounting for the changes leading to the inception of the BRI, the relationship between the BRI and its purported outcomes may still be spurious, i.e., they may be affected by a third factor. Consider globalization as an example. Since its economic liberalization in the 1980s and entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has been expanding its economic ties globally. Beijing has encouraged businesses to invest abroad since the early 2000s [49]. Irrespective of the BRI, China has become the world’s manufacturing hub and a key investor in and creditor to many countries. The BRI may thus be a logical next step in consolidating and enhancing these existing advantages.

Viewed in this manner, the trend of globalization may explain both the economic linkages between China and other countries and the inception of the BRI. Furthermore, some scholars have suggested that the BRI’s structure was determined by economic interests that were established before Xi’s rise to power, and the BRI simply agglomerated and scaled up many existing projects [36, 56]. Therefore, even if there has been an increase in, for example, the level of investment in some economies from China in the BRI era, this increase may well be a continuation of the trends of globalization, economic development, and political initiatives that originated decades ago.

The spurious (or reverse) causal relationship is also likely to operate at the country level, due primarily to political factors. For instance, whereas some studies have argued that diplomatic linkages to China or the US affect regime types, Wong [54] demonstrated that countries in the process of democratization may strengthen their relationship with the US whereas countries that are becoming more autocratic may do so with China, thus reversing the assumed causal flow. This logic can be extended to the BRI, as regimes that are autocratizing (or have a populist leader seeking to undermine democracy) may be more likely to participate in the BRI (e.g., to attract investments and increase their legitimacy). Similarly, given the resources involved in the BRI, it may present an opportunity for corruption in many developing economies participating in the initiative. Shah [51] highlighted that many countries involved in the BRI have weak institutional frameworks, hinting at the possibility that corrupt governments may be more enthusiastic about jumping on the BRI bandwagon to exploit the potential for the embezzlement of its resources. In sum, rather than it being that the BRI facilitates autocratization or corruption, it may be that countries prone to such developments are associated with participation in the BRI.

In this study, we propose two main arguments. First, we argue that BRI participation is potentially endogenous to the very outcomes that have typically been hypothesized to be the consequences of the project, thereby rendering a simple estimation of its effects to be problematic. All else being equal, countries that are economically linked with China are more likely to be on good terms with it and thus more likely to become part of the BRI. By the same token, countries that adopt a more cautious view on the rise of China are more likely to see the BRI as a political project, strengthening their reluctance to participate (they might additionally attempt to “de-risk” by decreasing their linkages with China).

Second, building on the first argument, we argue that the trends of economic linkages with China would have differed between countries with different levels of participation in the BRI not just after but also before the formal commencement of the BRI. The next section analyzes the trends in linkages leading up to the commencement of the BRI by participation levels to distinguish ongoing trends from actual impact and highlights some of the strategic calculations behind the BRI.

Analyzing the BRI

The coverage of the BRI is a point of contention. Despite fledgling discourses on the issue, the scope of the BRI, both geographically and in terms of its constituent activities, has never been specified and has perhaps deliberately been kept vague to accommodate diverse interests [36]. For example, the countries included in the “corridors” can only be estimated due to the lack of available details,even in cases in which the corridors are drawn, they do not correlate significantly with project activity [32]. Furthermore, with no clear criteria as to what qualifies as a BRI project, the label has been flexibly applied to a range of initiatives constituting an “endless list of unrelated activities” [32], 5). The classification of projects as belonging to the BRI or not, however, is crucial in this research to estimate the impact of the BRI.

In this study, our source of information was the official website of the BRI, the Belt and Road Portal (www.yidayilu.gov.cn), which maintains an updated list of countries that have signed documents on cooperation with China on the BRI (131 countries as of June 2019).Footnote 3 However, these documents mainly consist of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) (liangjie beiwanglu), Joint Statement (lianhe shengming), Joint Communiqué (lianhe shengming), Protocol (yidingshu), and Agreement (xieyi), all of which differ from each other in their significance, formality, and whether they are legally binding. Furthermore, the statuses of documents such as the MoU are difficult to determine except by studying all of their terms.Footnote 4

In addition to the list of official BRI cooperation documents, there are nevertheless other informal agreements that were signed during the first and second Belt and Road Summits, in 2017 and 2019, respectively. The informal agreements were included in the List of Deliverables (chengguo qingdan) released at the two summitsFootnote 5; however, they did not feature in the formal list on the portal. Whereas the official list mainly covers cooperative documents signed by national governments, the informal agreements are often signed by sub-national authorities and enterprises and are mainly aimed at building cooperative relationships in specific areas such as energy and science and technology. These agreements typically indicate a willingness to cooperate at a lower level, and are often pursued without the “BRI” label (otherwise, they would have been included in the main list). Whereas the formal participant countries were represented by their state leaders (e.g., Russia was represented by President Vladimir Putin at the BRI summit in 2017), state leaders from the US and G7 countries were notably absent from the summits [45]. However, many of them have been involved informally in the BRI.

The US delegation participated in the summits and agreed to some cooperation in the academic and financial domains. These cooperation agreements were all enterprise-rather than government-driven. Another example is Switzerland, which participated in both the forums and signed four agreements. However, the signatories were not the head of the government but companies and individual departments. Only one agreement (in the area of quality supervision, inspection, and quarantine) contained a vague reference to “building the Belt and Road.” It may be argued that this group of informal participants were not keen on a new China-led international order but might be prepared to jump on the BRI bandwagon should the economic gains of doing so become irresistible.

Therefore, in our main analysis below, we divide countries into three groups. First, the “formal participants” are countries that signed a formal agreement under the BRI framework (regardless of the nature of the document). This definition is quite broad as it includes all of the 131 countries that formally agreed to join the initiative (the statistical analysis includes 116 countries due to data availability). They are, nonetheless, likely to constitute the group that is most likely to exhibit an effect, because these countries at least signaled an intention to be involved. Second, 21 countries from which enterprises and authorities signed cooperative agreements on BRI projects during the summits are grouped as “informal participants.” Finally, the remaining countries that had no involvement in the BRI form the group of “non-participants.” A full list of the formal and informal participants, with the details and format of their involvement, is provided in the Appendix.

Potential BRI Outcomes

Although initially it was largely unclear exactly what it would mean for a country to be a BRI partner, the general view was that Chinese investments would follow [45] and that there would be more extensive economic cooperation across various domains such as trade and infrastructure. To comprehensively assess such linkages, we examine both passive and active economic indicators. Passive linkages include the flow of goods between China and the target economy. While the BRI can be viewed as an economic initiative to expand the markets for China’s products, the initiative also enhances its potential to secure the resources it desires. Figures of imports from China (Imp-CN) and exports to China (Exp-CN) for each economy (in million USD) are taken from the International Monetary Fund Direction of Trade Statistics.Footnote 6 It can be argued that passive linkages are more susceptible to factors not in China’s control, such as the domestic demand in and competitiveness of products from other economies.

Within the context of the BRI, we must also consider economic indicators that China can control and manipulate, i.e., the active linkages of outward investment and aid to other economies. Following Bader [3], Chinese investments in other economies can be captured using the annual turnover of all projects (in million USD) implemented by Chinese companies (Investment).Footnote 7 Detailed data by target economy were obtained from various issues of the China Statistical Yearbook published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China. In this study, Aid amount refers to the total amount of aid (in million USD), including official developmental assistance and other official flows, from China to other economies by year. Data were also obtained from the AidData Global Chinese Official Finance dataset [23]. The dataset captures all known officially funded Chinese projects around the world, including concessional and non-concessional sources from all Chinese government institutions and development, commercial, and representational projects.Footnote 8 Although these data are limited due to “hidden” and “underreported” loans [8], we utilize the dataset because of its unique nature and wide coverage. The raw values of these four outcome variables (Imp-CN, Exp-CN, Investment, and Aid amount) are used as dependent variables in the regression models.Footnote 9

Political Correlates of the BRI

As suggested in this paper, political factors might determine participation in the BRI in the first place and also be affected by the BRI in turn. In this study, we focus on two such factors: corruption and the type of regime. The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project dataset was used to obtain data on corruption and the type of regime [19]. The V-Dem dataset is an encompassing cross-country dataset on political and regime characteristics over time constructed by aggregating inputs from a vast pool of country experts. In the dataset, corruption is indicated by the public sector corruption index, which captures the extent to which “public sector employees grant favors in exchange for bribes, kickbacks, or other material inducements” as well as the frequency of embezzlement of public resources. The level of democracy is indicated by the V-Dem polyarchy index, which is calculated using a similar methodology. For both indices, a higher value represents a better government system (i.e., more democratic or less corrupt).

Analyses

To test the arguments discussed above, we first conduct a descriptive analysis of the trends of the main economic and political correlates of the BRI. In the context of BRI participation, it may be argued that the trends prior to the commencement of the BRI might have already been different by the 2010s, making a narrow focus on post-BRI (post-2013) changes problematic. To illustrate this point, we plot the outcomes for all of the countries grouped by their participation in the BRI. The quadratic plots are fitted to allow for an inflexion point (where they changed from concave to convex, or vice versa). If the effect of the BRI is significant, there should be an observable upward shift following the announcement of the BRI exclusively for the participant groups. The effect would be questionable if (1) there was no upward shift in their levels in the BRI era, or (2) such a change also occurred for non-participants. This analysis covers the period from 1999 to 2017, capturing the full impact of China’s admission to the World Trade Organization in 2001.

Although the above analysis is illustrative, it is largely descriptive and does not account for potential confounders. Further, the differences in the outcome variables pre- and post-BRI are not tested statistically. In this regard, a simple difference-in-differences (DiD) model can be used to assess the effect of the BRI on the participating countries’ linkages with China.Footnote 10 A similar estimation strategy has been used in studies on how regulatory regimes affect investment [14] and in studies on the effects of the BRI [24]. Because the BRI was first announced in September 2013, we treat the period starting from 2014 as the “post-treatment” period.Footnote 11 In addition, as we are interested in determining whether an increase in economic linkages might have been attributable to a long-term rise prior to the BRI, we include a trend variable counting the number of years. The regression equation is as follows:

The dependent variables in the equation are the economic linkage indicators discussed above; i and t denote the country and year of observation; β denotes the coefficients to be estimated; X is a vector of the control variables; and ε is the error term. ν is the country fixed effects and captures all time-invariant country-specific variables including cultural ties and geographical proximity to China.

Numerous control variables are included in the regression model. Domestic economic factors of the host economy are included because they are obvious predictors of BRI involvement. GDP (in USD, logged) is included to capture the size of the economy, whereas the rates of annual GDP growth and unemployment reflect the economy’s health and vulnerability because these factors might also affect BRI participation. Because the extent of natural resources available in an economy determines its economic capacity and its strategic value to China, oil rent as a share of GDP is included. To capture the degree of economic openness, the levels of import, export, and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow (all as a share of GDP) are included. Finally, from a political viewpoint, regime affinity is also an important factor for BRI participation [31]. Therefore, the V-Dem polyarchy index discussed above is also included. Unless otherwise stated, data from the World Bank World Development Indicators are used in this analysis. Descriptive statistics of the variables used in this article are reported in the Appendix.

Descriptive Analysis

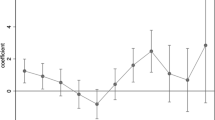

Before we investigate the economic linkages, we examine the political correlates of BRI participation. Figure 1 shows the trends (in quadratic plots with 95% confidence intervals) of democracy and corruption in countries grouped by their BRI participation. For ease of comparison, both indicators are indexed to 1 in 1999 for all of the countries included. The figure reveals that whereas the democracy indicators of the formal participants increased most over time, followed by those of the non-participants to a lesser extent, neither of these trends emerged only after the commencement of the BRI and the commencement did not alter their trajectories. The corruption trends also present a surprising finding: the formal participants’ level of corruption improved over time, whereas that of the informal participants and non-participants largely remained unchanged. Interestingly, the inter-group differences became significant and heightened during the BRI period. These observations provide tentative evidence that to the extent that the logic of selection explains BRI participation, the effects are contrary to expectations: the BRI does not “export” authoritarianism, and participants of the BRI do not experience worsened corruption as a result of their participation.

Trends of Democracy and Corruption by BRI Participation. Notes: Fitted quadratic graphs (with 95% confidence intervals) of the levels of democracy and corruption, grouped by countries’ participation in the BRI. Values at 1999 are indexed to 1. A higher value represents more democracy/less corruption. The year of the announcement of the BRI (2013) is marked with a vertical dotted line

Figure 2 presents plots of the four types of linkages of countries with China over time (imports and exports indexed to 1 in 1999). For all of the indicators, whether passive (import and export) or active (investment and aid), the formal participants exhibit the highest extent of linkages, as expected. However, the hypothesized surge in linkages caused by the BRI is absent across the indicators. Rather, the inter-group differences had already developed in the period leading to the BRI. In fact, non-participants imported more from China in the post-2013 period, closing the difference in imports with formal participants. Indeed, except for Chinese investments, the differences in the extent of linkages are not statistically significant (i.e., the confidence intervals overlap). Thus, all things considered, it can be argued that the BRI does not have a strong impact on a country’s economic linkages with China. This finding does not necessarily mean that China has not put substantial effort into cultivating economic ties (as evidenced by the figures of its investments), but rather that such an effort, to the extent that it has been made, either began long before the BRI or is not strongly differentiated between the country groups.

Trends of Chinese Economic Linkages by BRI Participation. Notes: Fitted quadratic graphs (with 95% confidence intervals) of the value of imports, value of exports, turnover of Chinese investments, and aid amount, grouped by countries’ participation in the BRI. Values of imports and exports are standardized as % of GDP of host economy and indexed to 1 at 1999 for easy comparison. The year of the announcement of the BRI (2013) is marked with a vertical dotted line

The second observation regarding linkages between other economies and China, which builds on the first, is that the trends prior to the BRI were largely correlated with the countries’ eventual level of BRI participation. The passive linkages (import and export) with the informal participants of the BRI barely increased over the past two decades, whereas the formal participants and non-participants had established stronger trading linkages with China by 2010. In terms of the active linkages, the non-participants lagged behind the other two groups in general; this difference was clearly significant for investments but only marginally significant for aid. Nonetheless, the cross-group differences were already identifiable by 2010. Based on the plots for all four kinds of linkages, we tentatively conclude that economic linkages and BRI participation are endogenous, i.e., the direction of causality is not clear.

Furthermore, assuming that China has greater control over the active indicators (i.e., the decision of which countries to invest in or send aid to), the plots clearly show that China has traditionally been more active in building influence over countries that are now formal participants in the BRI; non-participants received the least amount of investment and aid throughout the period. To the extent that China has some influence over these linkages, it can be argued that they have been used as incentives to further China’s economic influence in this group of countries, which in turn has brought them on board the BRI. Overall, although it is true that formal participants received the most Chinese investment and aid, it is not because of the BRI; rather, it might be because of the linkages in the past two decades that prompted them to become formal BRI partners.

Regression Analysis

Table 1 presents the results of the regression on the active indicators of economic linkages, namely investment turnover and development aid amount. Eight estimations are performed for each dependent variable based on participation in the BRI (formal participants, informal participants, and non-participants, plus a model pooling all observations) and with or without a trend variable. The trend variable captures the fact that China has been expanding all kinds of linkages with the rest of the world at least since it joined the World Trade Organization about two decades ago. Some of the estimations omitted from the Table are reported in the Appendix. Because country fixed effects are included in all of the statistical models, the captured effects are attributable to within-case changes over time, supplementing the cross-country variations above. The table shows that GDP is a strong predictor of Chinese investment, and the effect of GDP on investment is significant across all groups, particularly among the formal participants. The effect of oil rent on investment, however, is negative and significant only among the formal participants. The main variable, BRI, does not have a consistent impact on investment across all models. Its influence on investment is positive and statistically significant (p < 0.01) only in the model with formal participants (3) and the aggregated model (4). Removing the trend variable also makes the coefficient of BRI in model 2 significant, but only marginally (p < 0.1; results in the Appendix). Next, for developmental aid (models 5–8), the effect of GDP is positive and significant only for formal participants. The effects of BRI are much weaker and do not attain significance in any group. While the trend variable is significant for the formal group, indicating an increasing aid received by these countries over time, removing it does not substantively change the effect of BRI (Appendix).

Table 2 presents the results on trade flows between China and other economies using the same model specifications as above (control variables not shown). For Chinese imports (models 9–16), the coefficient of BRI is only significant in the informal group (p < 0.05) and marginally significant in the aggregated group. However, its sign is opposite to our expectation, i.e., there was a decrease in Chinese imports following the commencement of the BRI. The pattern is similar for exports to China (models 17–20), with BRI only attaining significance in the aggregated group (model 20), again in the negative direction. The trend variable is, as expected, positive across all specifications and significant in several groups, including the aggregate models. Critically, removing the trend variable changes the results: all BRI variables become positive and most become statistically significant. These findings are discussed further in the next section.

Case Studies

We supplement the statistical analysis by drawing on two mini case studies to demonstrate (a) how pre-BRI economic effects determined BRI participation and (b) that the overall economic effects of the BRI were limited. We selected the European Union (EU) as it is a relatively homogenous region (in comparison with other regions) that has exhibited increased investment and interaction with China for the past decades. The EU is also a key region for the BRI in terms investment and infrastructure projects [20]. Furthermore, EU–China relations have transformed significantly during the post-2017 period in a manner that has several important implications, causing divisions between western and eastern member states [35].

We considered the cases of all countries in the EU involved in the BRI and selected two based on factors such as BRI participation, political change, and pre- and post-BRI linkages (see Table A.6 in the Appendix for further details). Hungary and Italy were chosen to enable us to examine and contrast the dynamics of the engagement of two economically medium-sized EU countries with formal BRI status. Hungary has been experiencing a democratic backsliding while seemingly embracing stronger connections with China (i.e., a “most-likely” case for the BRI to exert an effect); Italy, in contrast, is a key EU state that has made high-profile overtures to the BRI, much to the world’s surprise. Table 3 illustrates several factors pertaining to the two countries, including political status, the EU’s attitude toward them, their reception of the BRI, and the changes in Chinese investment levels in the countries before and during the BRI era. Both cases demonstrate a similar pattern regarding the relative importance of Chinese investments, as the increase in the flow of investment was much larger before than after the commencement of the BRI (Hungary registered a small decrease in investment in the BRI period), hinting that the economic effects of the BRI were limited. In addition, the selection of the two countries precluded the possibility that a difference in prior economic factors determined differences in their reception of the BRI.

Overall, the Hungarian case demonstrates how the BRI has been an attractive economic scheme for the government. Hungary’s political system has undergone autocratization and increasingly experienced disputes with the EU in recent years. Although these events were not directly related to the BRI, the fact that Hungary’s involvement in the BRI has occurred concurrently with its international realignment reinforces our main argument that the BRI is a product of prior international relations. In contrast, the Italian case is more nuanced in that it demonstrates that the country’s participation in the BRI was purely a result of economically motivated decisions made by a succession of coalition governments, although it had no (or limited) observable economic effects when the country exited the BRI in December 2023.

Case Study: Hungary

Hungary has been an active participant in the BRI (16 + 1 Member), having signed a formal MoU with China in 2015 (see [43, 47],). Hungary is notably also the first participant among European countries. Some scholars have argued that Hungary’s unique geography has made the country attractive to China [28], whereas others have viewed the country as a gateway to not only the EU [47] but also the wider Central-Eastern European (CEE) region (as it is part of the Visegrád Group consisting of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) for Chinese investments.

Hungary is also a relatively new member of the EU, having joined in 2004 as part of the enlargement of the EU into Eastern Europe. In recent years, the country has been witnessing democratic backsliding under the ruling far-right Fidesz government with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán at the helm [22]. In addition, the EU has imposed sanctions on Hungary for violations of the rule of law (weakening of the judiciary and NGOs and consolidation of power by the executive) and illiberalism in 2018–2019 (see [22, 47].Footnote 12

Recent economic linkages between China and Hungary have included a new 350 km-long high‑speed railway link (expected to be completed in 2025) between Budapest and Belgrade in Serbia that would allow Chinese goods direct access into the European market. Other initiatives include a plan announced in 2022 for a Chinese battery giant (CATL) to build a factory in eastern Hungary for around $7.7 billion. Hungary’s increasingly isolated position in the EU might also cause Orbán to further intensify Hungary’s economic engagement in China’s BRI.Footnote 13

Between China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (1999) and the commencement of the BRI (2013), the volume of Chinese investment into Hungary increased by about 5.6 times.” In contrast, the figure more or less remained the same in the period immediately following the commencement of the BRI (a change of 0.998 times from 2013 to 2017). Both figures demonstrate that Hungary benefited much more in terms of Chinese investment from the economic effects that preceded BRI.

It is important to note that Hungary’s continued autocratization is likely to have had little relation to Chinese investments or its participation in the BRI. Although it is conceivable that under Orbán’s government, Hungary may become increasingly receptive to future Chinse investments and economic linkages related to the BRI, our argument remains that Hungary’s involvement in BRI is likely to have resulted from its international realignment, and that the overall economic effects of the BRI have in fact been limited.

Case Study: Italy

In contrast to Hungary, Italy is a founding member of the EU (which began as the European Communities in 1958). Italy became the first G7 country to sign a formal agreement with China on the BRI via an MoU in 2019. Consequently, the EU has been critical of Italy’s involvement in the BRI [18]. Some researchers have argued that the country’s entry into the BRI in 2019 was a purely economic decision for the Italian government [21]. Scholars have also agreed on the significance of the economic dimension of the BRI, considering the investment flows and infrastructure projects that may have resulted from it, for Italy’s struggling economy (see [21, 26]. Italy also arguably viewed China as a strategic economic partner and sought to expand its foreign trade and FDI flows with China [44].

Nevertheless, in recent years, Italian politics has often been characterized by high levels of political volatility (see [10]. Between 2018 and 2023, Italy experienced three short-lived coalition governments. The frequent changes in the ruling political parties and government personnel have affected the Italy–China partnership in relation to the BRI [55]. Whereas the Conte I Cabinet (2018–2019) of the Italian Five Star Movement Party and The League Party oversaw the signing of the MoU with China in March 2019, the attitudes of the subsequent governments toward the BRI were comparatively negative [55]. The Conte II Cabinet (2019–2021) featured a coalition between the Five Star Movement and the center-left Democratic Party, with the former supporting economic co-operation with China and the latter opposing it. The Draghi Cabinet (2021–2022), which featured a coalition of various parties of right- and left-wing ideologies, was more pro-EU and adopted a risk-averse stance toward dealing economically with China.

An examination of the figures of Itay’s pre- and post-BRI economic linkages with China (Table 3) demonstrated a similar (if not stronger) pattern to those of Hungary. China’s investment in Italy increased about 9.35 times from 2001 to the commencement of the BRI (2013), whereas the corresponding increase in the subsequent years (2.02 times) was far less pronounced (although it still doubled). Evidently, like Hungary, Italy benefited much more in terms of Chinese investment from the economic effects that occurred prior to 2013.

The latest government, a far-right coalition under Giorgia Meloni (2023–) decided to formally exit the BRI in December 2023. This move was consistent with Xiao and Parenti’s 55 observation that there has recently been a significant shift in Italian foreign policy favoring stronger relations with both the EU and the US. The issue of “revolving doors” (a succession of frequently-changing national-level governments) and Italy’s high levels of economic debt were likely to have led to its more cautious approach. Recent geo-political developments have additionally revealed how the EU sought to limit Italy’s economic co-operation with China in the post-COVID-19 period and also targeted smaller EU states in this regard, suggesting that the EU views the BRI as a direct political challenge [18]. In summary, we argue that Italy’s decision to join the BRI in 2019 was a purely economic and pragmatic decision taken by the then Italian government (in the anticipation of an influx of Chinese investments, as had occurred in the decade prior to the BRI), a decision that resulted in no observable economic effects and was reversed four years later when Italy ended its participation in the BRI.

Discussion

Our analysis of active economic linkages shows that China expanded its levels of investment in the post-BRI era, and that these investments were the highest in the economies of the formal participants. To the extent that investment is a key aspect of the activities of the BRI for participating economies, this finding suggests that China’s current focus (after 2013) is on those economies that have joined the initiative. Whereas this finding might illustrate the economic utility of the BRI framework for transferring Chinese capital to participating countries, we must bear in mind that this group was leading in the receipt of investment from China well before the BRI (as suggested by the descriptive analysis). Thus, either these countries have traditionally been aligned with China, which simultaneously explains their receipt of investments and inclusion in the BRI, or previous Chinese investments have been successful in bringing them on board. This does not mean that the BRI is ineffective or even symbolic, but indicates that the BRI is more an end than a means to China. The BRI is largely a reflection of China’s extant diplomatic links (with countries that have been welcoming Chinese investments both before and after the initiative) rather than a strategy that can transform the geopolitical landscape, as it has not opened up new markets for Chinese investments (given its insignificant effect on informal participants and non-participants).

The positive association between investment and GDP suggests that either Chinese investment in countries increased with the size of their economies or that their economies grew due to greater investment inflow, or a combination of both. As a thorough discussion on this issue is beyond the scope of this article, it suffices to say that the BRI does not particularly focus on underdeveloped economies, as some of the official rhetoric suggests (otherwise, the association between GDP and investment would have been negative). The role of oil in Chinese investment is also noteworthy, as the coefficient of oil rent is negative for the participant group. To an extent, this finding reinforces our argument regarding the limited geopolitical significance of the BRI, which has been purported by some as an effort to secure strategic resources for China. Because oil-rich countries are more resourceful, they rely less on Chinese investments (even if they become BRI members). The finding reflects the fact that the BRI has been less successful in entering countries that are oil-rich than in those without such resources. The results for the relationship between BRI participation and development aid, the other active linkage examined in the study, are similar. We do not find any evidence that the BRI has had any concrete impact on the amount of aid that China sends to recipients, regardless of the group they belong to. China has gradually been increasing its aid to countries that belong to the group of formal participants. However, this trend started well before the BRI, again reflecting the nature of the BRI as a label for countries with whom China has had existing links.

Next, the results on the impact of the BRI on the passive indicators that capture trade depend on whether we account for trends prior to the BRI. This finding raises a crucial question regarding the research design that should be adopted for such problems: should we de-trend data when assessing the impact of the BRI? We argue that it is more appropriate to do so than not. China’s economy has become increasingly integrated with those of countries worldwide over the last two decades, and a continuous upward trend in trade between China and other countries is obvious in our figures. If this trend is not accounted for, any observed effect of the BRI would simply mean that the levels of the economic linkages have on average been higher since 2013 than before, which is not surprising given the growth in China’s economy and deepening globalization. Any economic impact attributed to the BRI must constitute a separately identifiable effect above and beyond those of the ongoing economic trends prior to 2013. As such, we conclude that the BRI fails to demonstrate such a distinct impact on economies that have linkages with China.

The comparative case study illustrates the political and economic nuances of participation in the BRI: the Hungarian case demonstrates the political and economic nature of the BRI, whereas the Italian case demonstrates how the country’s reception of the BRI has largely been an economic decision by its government. Taken together, both case studies illustrate (a) how pre-BRI economic linkages have determined the level of engagement with the BRI and (b) the extent to which the overall economic effects of the BRI have been limited. These findings reinforce both the main arguments proposed in this study and the patterns identified in the quantitative findings.

Conclusion

By examining four types of economic linkages between China and other economies, supplemented by case studies on Italy and Hungary, this study provides an objective assessment of the political and economic impact of the BRI. The BRI has been subject to much controversy and discussion, both inside and outside of academia. However, there has been little empirical research on its real impact, limiting our ability to systematically understand the role played by the BRI in China’s rise. Most studies on the topic have been case studies on the development and impact of individual projects in a country or region. Empirical studies on the topic have seldom accounted for the fact that the BRI, economic development, and diplomatic relations are all endogenous. This study provides a reassessment of the impact of the BRI while accounting for the fact that the BRI might in itself be a reflection of the pre-existing (and ongoing) economic and political connections between China and the world.

Therefore, although this study did not aim to resolve the issue of endogeneity (which is challenging to do in this context),Footnote 14 it accounts for China’s existing economic linkages prior to the announcement of the BRI, which had been growing for at least two decades, to observe the true impact of the BRI. In addition, this study classifies countries into three groups according to their level of participation in the BRI. This classification not only enables us to avoid making the unrealistic assumption that the BRI’s impact is uniform across all countries, but also provides us with important insights into China’s activities under the BRI Project.

Several findings emerge from our preliminary assessment and descriptive analysis of select political and economic indicators. First, the encompassing nature of the BRI, with more than 116 formal members (as analyzed here), almost guarantees that it will not be an “autocracy club” (as some perceive the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to be). Much to the contrary, we find that the democracy levels of the formal participants were increasing prior to the BRI and show no signs of decreasing in the BRI period. The findings are similar for corruption levels: although the BRI was alleged by some as being conducive to corruption, this does not appear to be the case across all participants. This finding does not imply that the BRI and its projects are free from corruption, or that the projects somehow improve the situation regarding corruption in the recipient economies. It may be that the effect of the BRI on corruption is not consistent among all of the formal participants and is therefore not statistically significant. Conversely, it is also the case that people’s scrutiny of such foreign projects provides an important check on government activities, as evidenced by experiences in several high-profile BRI projects in Southeast Asia (e.g., [27].

Second, the three groups of countries (categorized by their subsequent level participation in the BRI) formed coherent and distinct patterns of economic linkages with China not just after but even before the BRI commenced. For some groups, a surge in the intensity of economic linkages could be seen in the early 2000s, well before the BRI period. Both observations support the argument that the development of the BRI has been determined by China’s ongoing linkages with other economies, and it is therefore inappropriate to adopt a straightforward estimation of the BRI’s effect that does not consider ongoing linkages. The follow-up statistical analysis further reinforces the finding that the impact of the BRI is largely limited to investments flowing to formal participants, especially after pre-existing trends are factored into consideration. Taken together, it can be argued that the BRI does not in itself have a significant impact but that it is more appropriate to view it as a reflection of China’s diplomatic relations with other countries. That is, a country’s traditional standing with China explains its level of participation in the BRI. The findings on the active linkages, over which China has greater control, also show that it is keener on cultivating ties with countries outside of the scope of the BRI.

Third, this study distinguishes non-participants from “informal” participants, i.e., countries with unofficial involvement with the BRI, typically represented by civil and commercial delegations at the BRI summits. Although this distinction does not affect the results substantively, it is important for future studies to make a similar distinction between these groups for two main reasons. First, the informal group consists of major western economies including the US, UK, France, and Germany, as well as those traditionally aligned with the US such as Japan. Despite their informal involvement in the BRI, the statistical results show that this group’s imports from China decreased significantly in the BRI period (after taking away the upward trend over time); the descriptive analyses show that their increase in trade with China has been modest compared with that of the formal participants and non-participants. Therefore, from a theoretical standpoint, it would be interesting to understand the stance of this group toward the BRI, a China-oriented effort with the potential to re-shape the dominant world order, especially against the backdrop of the ongoing US–China trade conflicts. Second, as these countries’ informal cooperative frameworks under the BRI usually focus on specific areas, many of which are not related to economic linkages, it is crucial for research on the non-economic aspects of the BRI to account for these potential areas as well.

Finally, it must be reiterated that this study does not dismiss the scope and reach of the BRI or its potential implications. As highlighted by the vast literature on the topic, the economic and political resources invested into the BRI by China are anything but negligible. The projects that are part of the initiative also have significant economic, social, and political implications for the host economy. The study merely highlights the importance of a more careful investigation into the BRI’s real impact that considers pre-BRI trends alongside China’s involvement with those countries currently outside of the BRI’s scope. Although the study mainly focuses on economic linkages, as they are the most notable correlates of the BRI, future studies should apply the same caution when examining the political impact of the initiative, such as in the issue of whether China has become more influential in other countries because of the BRI. Again, a country’s involvement in the BRI could be attributed to the same reasons for its diplomatic or economic inclination toward China in the first place.

Data Availability

Replication data are available upon request.

Notes

“China’s mammoth Belt and Road Initiative could increase debt risk for 8 countries”, CNBC, March 5, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/03/05/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-raises-debt-risks-in-8-nations.html. Accessed April 22, 2023.

Maria Abi-Habib, “How China Got Sri Lanka to Cough up a Port,” New York Times, June 25, 2018.

Whereas the “Belt and Road database” provided by the Social Sciences Academic Press contains information about the BRI, it does not provide a clear list of the countries participating in it. Researchers have to compile this information based on the reports and data on the portal (e.g., [24]). In addition, the information in this database does not appear to be frequently updated, and the database cites the portal used in this study as being one of its sources of information.

Many of the agreements have not been made available to the public in full.

“List of Deliverables of Belt and Road Forum,” Xinhuanet, May 15, 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com//english/2017-05/15/c_136286376.htm; “List of Deliverables of the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation,” China Daily, April 28, 2019, at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/newsrepublic/2019-04/28/content_37463762.htm. Accessed 3 July 2022.

The are substantively similar when the logged term is used instead.

Although this measure also includes projects funded by international agencies successfully bid for by Chinese companies, the estimated share of such projects is not high (see e.g., [3].

However, as the value for the amount of aid was missing for about one-third of all projects, the raw number of projects recorded in the dataset is used as an alternative variable of interest. The results are mostly similar, with either the same specification or a negative binomial regression (not shown).

We opt not to standardize these variables as a share of GDP for two main reasons. First, the decision on how much investment China sends to another country should not depend on the size of the host economy. Second, changes in the flows of investment over time should be reflected in the variables (e.g., an increase in the investment amount should not be considered a decrease simply because of an expansion of the economy). This is appropriate because we also include GDP as a control variable and country fixed effects in the models.

Despite the trend plots, the parallel trend tests cannot reject the null of a parallel trend in the pretreatment period (i.e., the assumption of the DiD model holds).

It can be argued that many countries joined the BRI at a later date and thus the standard cut-off used here was inappropriate. We offer three responses to this argument. First, one of our arguments is that the actual impact of the BRI is limited as it is an outcome of existing relationships. In that case, it would be interesting to ask whether China has increased its economic efforts after the commencement of the BRI to cultivate more influence (this is also the reason for including non-participants in the analysis). Second, we obtain similar results (available in the Appendix) with alternative indicators of actual BRI participation. Finally, we also conduct DiD tests with multiple time periods, the results of which are presented in the Appendix.

These sanctions may have indirectly pushed Hungary towards developing a closer economic relationship with China and the BRI (i.e., an indirect ‘push’ effect of the EU on the Hungary and China relationship).

“Hungary is becoming more important to China. Viktor Orban and Xi Jinping bond over their anti-Americanism.” The Economist 24 May 2023.

Some potential instrumental variables (e.g., the average level of Chinese investment in a country’s region) were tested, but they did not satisfy the conditions necessary to be considered instruments.

References

Abbott, Kenneth W., and Duncan Snidal. 1998. Why states act through formal international organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution 42 (1): 3–32.

An, Jingjing, and Yanzhen Wang. 2023. The impact of the belt and road initiative on Chinese international political influence: An empirical study using a difference-in-differences approach. Journal of Chinese Political Science.

Bader, Julia. 2015. China, autocratic patron? An empirical investigation of China as a factor in autocratic survival. International Studies Quarterly 59: 23–33.

Barnett, Michael N., and Martha Finnemore. 1999. The politics, power, and pathologies of international organizations. International Organization 53 (4): 699–732.

Beeson, Mark, and Corey Crawford. 2023. Putting the BRI in perspective: History, hegemony and geoeconomics. Chinese Political Science Review 8: 45–62.

Blanchard, Jean-Marc F. 2017. Probing China’s twenty-first-century Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI): An examination of MSRI narratives. Geopolitics 22 (2): 246–268.

Blanchard, Jean-Marc F. 2020. Problematic prognostications about China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI): Lessons from Africa and the Middle East. Journal of Contemporary China 29 (122): 159–174.

Brautigam, Deborah, and Yufan Huang. 2021. What is the real story of China’s “hidden debt?” Briefing Paper, No. 06/2021, China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

Brownlee, Jason. 2012. Democracy Prevention: The Politics of the US–Egyptian Alliance. Cambridge University Press.

Bruno, Valerio A., James F. Downes, and Alessio Scopelliti. 2024. The Rise of the Radical Right in Italy. Columbia University Press/ibidem Press.

Büthe, Tim, and Helen V. Milner. 2008. The politics of foreign direct investment into developing countries: Increasing FDI through international trade Agreements? American Journal of Political Science 52 (4): 741–762.

Cai, Kevin G. 2023. China’s initiatives: A bypassing strategy for the reform of global economic governance. Chinese Political Science Review 8: 1–17.

Cai, Peter. 2017. Understanding China’s belt and road initiative. Lowy Institute for International Policy.

Cai, Xiqian, Lu. Yi, Wu. Mingqin, and Yu. Linhui. 2016. Does environmental regulation drive away inbound foreign direct investment? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Journal of Development Economics 123: 73–85.

Calabrese, Linda, and Cao Yue. 2021. Managing the belt and road: Agency and development in Cambodia and Myanmar. World Development 141: 105297.

Callahan, William A. 2013. China Dreams: 20 Visions of the Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chen, Huiping. 2016. China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative and its implications for Sino-African investment relations. Transnational Corporations Review 8 (3): 178–182.

Chen, W.A. 2021. COVID-19 and China’s changing soft power in Italy. Chinese Political Science Review 8 (3): 440–460.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, et al. 2019. V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v9, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemcy19

Dimitrijević, D., and N. Jokanović. 2016. China’s “new silk road” development strategy. The Review of International Affairs 67: 21–44.

Dossi, S. 2020. Italy-China relations and the belt and road initiative. The need for a long-term vision. Italian Political Science 15 (1): 60–71.

Downes, J.F., M. Loveless, and A. Lam. 2021. The looming refugee crisis in the EU: Eight-wing party competition and strategic positioning. Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (5): 1103–1123.

Dreher, Axel, Andreas Fuchs, Bradley Parks, Austin Strange, and Michael J. Tierney. 2017. Aid, China, and growth: Evidence from a new global development finance dataset. AidData Working Paper #46. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

Du, Julan, and Yifei Zhang. 2018. Does One Belt One Road initiative promote Chinese overseas direct investment? China Economic Review 47: 189–205.

Elkjær, Mads Andreas, and Michael B. Klitgaard. 2021. Economic inequality and political responsiveness: A systematic review. Perspectives on Politics. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721002188.

Fardella, E., and G. Prodi. 2017. The Belt and Road Initiative impact on Europe: An Italian perspective. China & World Economy 25 (5): 125–138.

Gong, Xue. 2019. The Belt & Road Initiative and China’s influence in Southeast Asia. The Pacific Review 32 (4): 635–665.

Gubik, A.S., M. Sass, and Á. Szunomár. 2020. Asian foreign direct investments in the Visegrad countries: What are their motivations for coming indirectly? Danube 11 (3): 239–252.

Gyamerah, Samuel, Zheng He, Emmanuel E.-D.. Gyamerah, Dennis Asante, Bright N. K. Ahia, and Enock M. Ampaw. 2022. Implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative in Africa: A firm-level study of sub-Saharan African SMEs. Journal of Chinese Political Science 27: 719–745.

Hall, Todd H., and Alanna Krolikowski. 2022. Making sense of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A review essay. International Studies Review 24 (3): viac023.

He, Baogang. 2019. The domestic politics of the Belt and Road Initiative and its implications. Journal of Contemporary China 28 (116): 180–195.

Hillman, Jonathan E. 2018. China’s Belt and Road is full of holes. Center for Strategic International Studies.

Hurley, John, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance. 2019. Examining the debt implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a policy perspective. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development 3 (1): 139–175.

Jenkins, Rhys. 2019. How China is Reshaping the Global Economy: Development Impacts in Africa and Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jones, C. 2021. Understanding the Belt and Road Initiative in EU–China relations. Journal of European Integration 43 (7): 915–921.

Jones, Lee, and Jinghan Zeng. 2019. Understanding China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”: Beyond “grand strategy” to a state transformation analysis. Third World Quarterly 40 (8): 1415–1439.

Kaliszuk, Ewa. 2016. Chinese and South Korean investment in Poland: A comparative study. Transnational Corporations Review 8 (1): 60–78.

Khanal, Shaleen, and Hongzhou Zhang. 2023. Ten years of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A bibliometric review. Journal of Chinese Political Science.

Kwong, Ying-ho, and Mathew Y. H. Wong. 2020. International linkages, geopolitics, and the Belt and Road Initiative: A comparison of four island territories. Island Studies Journal 15 (2): 131–154.

Landry, David G. 2018. The belt and road bubble is starting to burst. Foreign Policy 27.

Malik, Mohan J. 2018. Myanmar’s role in China’s Maritime Silk Road initiative. Journal of Contemporary China 27 (111): 362–378.

March, James G., and Johan P. Olsen. 1998. The institutional dynamics of international political orders. International Organization 52 (4): 943–969.

Matura, T. 2017. Chinese investment in Hungary: Few results but great expectations. In J. Seaman, M. Huotari & M. Otero-Iglesias (Eds)., Chinese investment in Europe. A country-level approach. ETNC Report: 75–80.

Men, H., and P. Jiang. 2020. The China-Italy comprehensive strategic partnership: Overview and pathways to progress. China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 6 (04): 389–411.

Nordin, Astrid H. M., and Mikael Weissmann. 2018. Will Trump make China great again? The Belt and Road Initiative and international order. International Affairs 94 (2): 231–249.

Reilly, James. 2021. Orchestration: China’s Economic Statecraft across Asia and Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rogers, S. 2019. China, Hungary, and the Belgrade-Budapest railway upgrade: New politically-induced dimensions of FDI and the trajectory of Hungarian economic development. Journal of East-West Business 25 (1): 84–106.

Rolland, Nadège. 2017. China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”: Underwhelming or game-changer? The Washington Quarterly 40 (1): 127–142.

Sauvant, Karl P., and Victor Zitian Chen. 2014. China’s regulatory framework for outward foreign direct investment. China Economic Journal 7 (1): 141–163.

Sending, Ole Jacob, and Iver B. Neumann. 2006. Governance to governmentality: Analyzing NGOs, states, and power. International Studies Quarterly 50 (3): 651–672.

Shah, Abdur Rehman. 2019. China’s Belt and Road Initiative: The way to the modern silk road and the perils of overdependence. Asian Survey 59 (3): 407–428.

Shambaugh, D. 2018. US–China rivalry in Southeast Asia. International Security 42 (2): 85–127.

Wang, Rui, Khai E. Lee, Mazlin Mokhtar, and Thian L. Goh. 2023. The transition of Belt and Road Initiative from 1.0 to 2.0: Challenges and implications of green development. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 16: 293–328.

Wong, Mathew Y. H. 2019. Chinese influence, US linkages, or neither? Comparing regime changes in Myanmar and Thailand. Democratization 26 (3): 359–381.

Xiao, Y., and F.M. Parenti. 2022. China-Italy BRI cooperation: Towards a new cooperation model? Area Development and Policy 7 (2): 204–221.

Ye, Min. 2020. The Belt Road and Beyond: State-Mobilized Globalization In China: 1998–2018. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zeng, Yuleng. 2021. Does money buy friends? Evidence from China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of East Asian Studies 21 (1): 75–95.

Zhang, Enyu, and Patrick James. 2023. All roads lead to Beijing: Systemism, power transition theory and the Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese Political Science Review 8: 18–44.

Zhao, Suisheng. 2019. China’s Belt-Road Initiative as the signature of President Xi Jinping diplomacy: Easier said than done. Journal of Contemporary China 29 (123): 319–335.

Zhou, Weifeng, and Mario Esteban. 2018. Beyond balancing: China’s approach towards the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of Contemporary China 27 (112): 487–501.

Zou, Yizheng, and Jones Lee. 2020. China’s response to threats to its overseas economic interests: Softening non-interference and cultivating hegemony. Journal of Contemporary China 29 (121): 92–108.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their helpful comments during the revision process. We would also like to acknowledge the research assistance provided by Wu Wenmiao and Huang Siwei.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors are not aware of any potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, M.Y.H., Downes, J.F. Reassessing the Impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A Mixed Methods Approach. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-024-09888-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-024-09888-0