Abstract

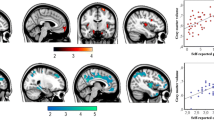

Independently, obesity and physical activity (PA) influence cerebral structure in aging, yet their interaction has not been investigated. We examined sex differences in the relationships among PA, obesity, and cerebral structure in aging with 340 participants who completed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition to quantify grey matter volume (GMV) and white matter volume (WMV). Height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index (BMI). A PA questionnaire was used to estimate weekly Metabolic Equivalents. The relationships between BMI, PA, and their interaction on GMV Regions of Interest (ROIs) and WMV ROIs were examined. Increased BMI was associated with higher GMV in females, an inverse U relationship was found between PA and GMV in females, and the interaction indicated that regardless of BMI greater PA was associated with enhanced GMV. Males demonstrated an inverse U shape between BMI and GMV, and in males with high PA and had normal weight demonstrated greater GMV than normal weight low PA revealed by the interaction. WMV ROIs had a linear relationship with moderate PA in females, whereas in males, increased BMI was associated with lower WMV as well as a positive relationship with moderate PA and WMV. Males and females have unique relationships among GMV, PA and BMI, suggesting sex-aggregated analyses may lead to biased or non-significant results. These results suggest higher BMI, and PA are associated with increased GMV in females, uniquely different from males, highlighting the importance of sex-disaggregated models. Future work should include other imaging parameters, such as perfusion, to identify if these differences co-occur in the same regions as GMV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in the present study are either publicly available (PREVENT-AD MRIs and demographics: https://openpreventad.loris.ca) or can be shared upon reasonable request and approval by the study scientific committees and/or institutional review boards. Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Pre-symptomatic Evaluation of Novel or Experimental Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease (PREVENT-AD) program (https://douglas.research.mcgill.ca/stop-ad-centre), data release 6.0. A complete listing of PREVENT-AD Research Group can be found in the PREVENT-AD database: https://preventad.loris.ca/acknowledgements/acknowledgements.php?date=%5B2022-08-02%5D.

References

S. C. Government of Canada. Overweight and obese adults, 2018, Jun. 25, 2019. Table 13-10-0096-01 Health characteristics, annual estimates. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2019001/article/00005-eng.htm. Accessed 8 Apr 2022. https://doi.org/10.25318/1310009601-eng.

Hruby A, Hu FB. The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(7):673–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x.

Livingston G, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6.

Pedditizi E, Peters R, Beckett N. The risk of overweight/obesity in mid-life and late life for the development of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Age Ageing. 2016;45(1):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv151.

Albanese E, et al. Overweight and Obesity in Midlife and Brain Structure and Dementia 26 Years Later. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(9):672–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwu331.

Masouleh SK, et al. Higher body mass index in older adults is associated with lower gray matter volume: implications for memory performance. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;40:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.12.020.

Pannacciulli N, Le DSNT, Chen K, Reiman EM, Krakoff J. Relationships between plasma leptin concentrations and human brain structure: A voxel-based morphometric study. Neurosci Lett. 2007;412(3):248–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2006.11.019.

Raji CA, et al. Brain structure and obesity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;31(3):353–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20870.

Walther K, Birdsill AC, Glisky EL, Ryan L. Structural brain differences and cognitive functioning related to body mass index in older females. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31(7):1052–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20916.

Moscovitch M, Winocur G. “The neuropsychology of memory and aging”, in The handbook of aging and cognition. Hillsdale, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1992. p. 315–72.

West R. An application of prefrontal cortex theory to cognitive aging. Psychol Bull. 1996;120:272–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.272.

Debette S, et al. Abdominal obesity and lower gray matter volume: a Mendelian randomization study. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(2):378–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.07.022.

Huang Y, et al. Interaction Effect of Sex and Body Mass Index on Gray Matter Volume. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:360. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00360.

Taki Y, et al. Relationship between body mass index and gray matter volume in 1,428 healthy individuals. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(1):119–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.4.

Cooper AJ, Gupta SR, Moustafa AF, Chao AM. Sex/Gender Differences in Obesity Prevalence, Comorbidities, and Treatment. Curr Obes Rep. Dec.2021;10(4):458–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-021-00453-x.

Schorr M, et al. Sex differences in body composition and association with cardiometabolic risk. Biol Sex Differ. 2018;9(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-018-0189-3.

Isacco L, Ennequin G, Boisseau N. Influence of the different hormonal status changes during their life on fat mass localisation in women: a narrative review. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2021;10:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13813455.2021.1933045.

Rathnayake N, Rathnayake H, Lekamwasam S. Age-Related Trends in Body Composition among Women Aged 20–80 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study”. Journal of Obesity. 2022;2022:e4767793. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4767793.

Arnoldussen IAC, Gustafson DR, Leijsen EMC, de Leeuw F-E, Kiliaan AJ. Adiposity is related to cerebrovascular and brain volumetry outcomes in the RUN DMC study. Neurology. 2019;93(9):e864–78. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008002.

Ho AJ, et al. The effects of physical activity, education, and body mass index on the aging brain. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32(9):1371–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21113.

Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3666. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3666.

Gunstad J, et al. Relationship Between Body Mass Index and Brain Volume in Healthy Adults. Int J Neurosci. 2008;118(11):1582–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207450701392282.

Hersi M, Irvine B, Gupta P, Gomes J, Birkett N, Krewski D. Risk factors associated with the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of the evidence. Neurotoxicology. 2017;61:143–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2017.03.006.

Colcombe SJ, et al. Aerobic Exercise Training Increases Brain Volume in Aging Humans. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2006;61(11):1166–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/61.11.1166.

Hamer M, Sharma N, Batty GD. Association of objectively measured physical activity with brain structure: UK Biobank study. J Intern Med. 2018;284(4):439–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12772.

Raichlen DA, Klimentidis YC, Bharadwaj PK, Alexander GE. Differential associations of engagement in physical activity and estimated cardiorespiratory fitness with brain volume in middle-aged to older adults. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(5):1994–2003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-019-00148-x.

Arenaza-Urquijo EM, et al. Distinct effects of late adulthood cognitive and physical activities on gray matter volume. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11(2):346–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-016-9617-3.

Halloway S, Arfanakis K, Wilbur J, Schoeny ME, Pressler SJ. Accelerometer Physical Activity is Associated with Greater Gray Matter Volumes in Older Adults Without Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(7):1142–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby010.

Rovio S, et al. Leisure-time physical activity at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurology. 2005;4(11):705–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70198-8.

Erickson KI, et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):3017–22. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015950108.

Erickson KI, Leckie RL, Weinstein AM. Physical activity, fitness, and gray matter volume. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(Suppl 2):S20–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.034.

Steffener J, Habeck C, O’Shea D, Razlighi Q, Bherer L, Stern Y. Differences between chronological and brain age are related to education and self-reported physical activity. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;40:138–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.01.014.

Chieffi S, et al. Neuroprotective Effects of Physical Activity: Evidence from Human and Animal Studies. Front Neurol. 2017;8:188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00188.

Intzandt B, et al. Comparing the effect of cognitive vs. exercise training on brain MRI outcomes in healthy older adults: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:511–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.07.003.

Varma VR, Chuang Y, Harris GC, Tan EJ, Carlson MC. Low-intensity daily walking activity is associated with hippocampal volume in older adults. Hippocampus. 2015;25(5):605–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.22397.

Casaletto KB, et al. Sexual dimorphism of physical activity on cognitive aging: Role of immune functioning. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:699–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.014.

Sanders A-M, et al. Linking objective measures of physical activity and capability with brain structure in healthy community dwelling older adults”. Neuroimage Clin. 2021;31:102767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102767.

Breitner JCS, Poirier J, Etienne PE, Leoutsakos JM. Rationale and Structure for a New Center for Studies on Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease (StoP-AD). J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3(4):236–42. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2016.121.

Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Bryant HE. The lifetime total physical activity questionnaire: development and reliability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(2):266–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199802000-00015.

Nasreddine ZS, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x.

Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–4. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a.

Tremblay-Mercier J, et al. (2021) Open science datasets from PREVENT-AD, a longitudinal cohort of pre-symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2021;31:102733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102733.

Albanese E, et al. Body mass index in midlife and dementia: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 589,649 men and women followed in longitudinal studies. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;8:165–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2017.05.007.

D’Agostino RB, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743–53. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579.

Song R, et al. Associations Between Cardiovascular Risk, Structural Brain Changes, and Cognitive Decline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(20):2525–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.053.

Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry–the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11(6 Pt 1):805–21. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2000.0582.

Gaser C, Dahnke R, Thompson PM, Kurth F, Luders E. Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative. CAT - A computational anatomy toolbox for the analysis of structural MRI data. 2022. bioRxiv. 2022.06.11.495736. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.11.49573.

Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal. 2008;12(1):26–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2007.06.004.

Shattuck DW, et al. Construction of a 3D probabilistic atlas of human cortical structures. Neuroimage. 2008;39(3):1064–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.031.

Raz N, Gunning-Dixon FM, Head D, Dupuis JH, Acker JD. Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive aging: Evidence from structural magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropsychology. 1998;12(1):95–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.12.1.95.

Resnick SM, Pham DL, Kraut MA, Zonderman AB, Davatzikos C. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies of older adults: a shrinking brain. J Neurosci. 2003;23(8):3295–301.

Crivello F, Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Tzourio C, Mazoyer B. Longitudinal Assessment of Global and Regional Rate of Grey Matter Atrophy in 1,172 Healthy Older Adults: Modulation by Sex and Age”. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(12):e114478. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114478.

Raftery AE. Bayesian Model Selection in Social Research. Sociol Methodol. 1995;25:111–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/271063.

Elliott AC, Woodward WA. Statistical analysis quick reference guidebook: With SPSS examples. SAGE; 2007.

Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S. Normality Tests for Statistical Analysis: A Guide for Non-Statisticians. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;10(2):486–9. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.3505.

J. Pallant, SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS, 7th ed. London: Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117452.

Pegueroles J, et al. Obesity and Alzheimer’s disease, does the obesity paradox really exist? A magnetic resonance imaging study. Oncotarget. 2018;9(78):34691–8. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.26162.

Gruberg L, et al. The impact of obesity on the short-term and long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: the obesity paradox? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(4):578–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01802-2.

Hayden KM, et al. Vascular risk factors for incident Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia: the Cache County study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(2):93–100. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wad.0000213814.43047.86.

Kim SE, et al. Sex-specific relationship of cardiometabolic syndrome with lower cortical thickness. Neurology. 2019;93(11):e1045–57. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008084.

Espeland MA, et al. Sex-Related Differences in Brain Volumes and Cerebral Blood Flow Among Overweight and Obese Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: Exploratory Analyses From the Action for Health in Diabetes Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(4):771–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz090.

Koenen M, Hill MA, Cohen P, Sowers JR. Obesity, Adipose Tissue and Vascular Dysfunction. Circ Res. 2021;128(7):951–68. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318093.

Vachharajani V, Granger DN. Adipose tissue: a motor for the inflammation associated with obesity. IUBMB Life. 2009;61(4):424–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.169.

Alfaro FJ, Gavrieli A, Saade-Lemus P, Lioutas V-A, Upadhyay J, Novak V. White matter microstructure and cognitive decline in metabolic syndrome: a review of diffusion tensor imaging. Metabolism. 2018;78:52–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2017.08.009.

Dekkers IA, Jansen PR, Lamb HJ. Obesity, Brain Volume, and White Matter Microstructure at MRI: A Cross-sectional UK Biobank Study. Radiology. 2019;291(3):763–71. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019181012.

Irimia A. Cross-Sectional Volumes and Trajectories of the Human Brain, Gray Matter, White Matter and Cerebrospinal Fluid in 9473 Typically Aging Adults. Neuroinform. 2021;19(2):347–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12021-020-09480-w.

Wood KN, Nikolov R, Shoemaker JK. Impact of Long-Term Endurance Training vs. Guideline-Based Physical Activity on Brain Structure in Healthy Aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2016.00155.

Lauer EE, Jackson AW, Martin SB, Morrow JR. Meeting USDHHS Physical Activity Guidelines and Health Outcomes. Int J Exerc Sci. 2017;10(1):121–7.

Barha CK, Best JR, Rosano C, Yaffe K, Catov JM, Liu-Ambrose T. Sex-Specific Relationship Between Long-Term Maintenance of Physical Activity and Cognition in the Health ABC Study: Potential Role of Hippocampal and Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Volume. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(4):764–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz093.

Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.90.

Wei M, et al. Relationship between low cardiorespiratory fitness and mortality in normal-weight, overweight, and obese men. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1547–53. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.16.1547.

Boidin M, et al. Obese but Fit: The Benefits of Fitness on Cognition in Obese Older Adults. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(11):1747–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2020.01.005.

Knight SP, et al. Obesity is associated with reduced cerebral blood flow – modified by physical activity. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;105:35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.04.008.

Grauer WO, Moss AA, Cann CE, Goldberg HI. Quantification of body fat distribution in the abdomen using computed tomography. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;39(4):631–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/39.4.631.

Karastergiou K, Smith SR, Greenberg AS, Fried SK. Sex differences in human adipose tissues - the biology of pear shape. Biol Sex Differ. 2012;3(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/2042-6410-3-13.

Chait A, den Hartigh LJ. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2020.00022.

Abdullah A, et al. The number of years lived with obesity and the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):985–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr018.

Power BD, Alfonso H, Flicker L, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Almeida OP. Changes in body mass in later life and incident dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(3):467–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212001834.

Strandberg TE, et al. Explaining the obesity paradox: cardiovascular risk, weight change, and mortality during long-term follow-up in men. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(14):1720–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp162.

Rathod K, et al. Sex differences in the inflammatory response and inflammation-induced vascular dysfunction. The Lancet. 2017;389:S20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30416-6.

Cohen E, Margalit I, Shochat T, Goldberg E, Krause I. <p>Markers of Chronic Inflammation in Overweight and Obese Individuals and the Role of Gender: A Cross-Sectional Study of a Large Cohort</p>. JIR. 2021;14:567–73. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S294368.

Hamer M, et al. Physical activity and inflammatory markers over 10 years follow up in men and women from the Whitehall II cohort study. Circulation. 2012;126(8):928–33. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103879.

Tardif CL, et al. Investigation of the confounding effects of vasculature and metabolism on computational anatomy studies. Neuroimage. Apr.2017;149:233–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.01.025.

Acknowledgements

CONSORTIUM – PREVENT-AD Research Group

Anne Labontéf,g, Alexa Pichet Binettef−h, Axel Mathieug, Cynthia Picardf−h, Doris Deaf,g, Claudio Cuelloh, Alan Evansg,h,i, Christine Tardiff,g, Gerhard Mulhauph, Jamie Nearf,h, Jeannie-Marie Leoutsakosk, John CS Bretinerf−h, Judes Poirierf−h, Lisa-Marie Müntermh, Louis Collinsg−i, Mallar Chakravartyf−h, Natasha Rajahf−h, Pedro Rosa-Netof−h, Pierre Bellecc,g,m, Pierre Etiennef−h, Pierre Orbanc,f,g,m, Rick Hogeg−i, Serge Gauthierf−h, Sylvia Villeneuevef−h, Véronique Bohbotf−h, Vladimir Fonovh,i, Yasser Ituria-Medinag−i, Holly Newbold-Foxf, Jacob Vogelf,g, Jennifer Tremblay-Mercierf,g, Justin Katf,g,i, Justin Mirong−i, Masha Dadarh,i, Marie-Elyse Lafaille-Magnanf−h, Pierre-François Meyerf−h, Samir Dash−i, Julie Gonneaudf−h, Gülebru Ayrancif−h, Tharick A Pascoalf−h, Sander CJ Verfaillief,g,n, Sarah Farzinf, Alyssa Salaciakf, Stephanie Tullof,h, Etienne Vachon-Presseauf,o, Leslie-Ann Daousg, Theresa Köbeg,h, Melissa McSweeneyh, Nathalie Nilssonf−h, Morteza Pishnamazif−h, Chirstophe Bedettif, Louise Hudong, Claudia Grecof,g, Frederic St-Ongef−h, Sophie Boutinf,g, Maiya R Geddesf−i, Simon Ducharmef−h, Gabriel Jeanf,g, Elisabeth Sylvainf,g, Marie-Josée Éliseg,h, Gloria Leblond-Baccichetf,g, Julie Baillyf, Bery Mohammediyanf,g, Jordana Remzf, Jean-Paul Soucyh,i

fDouglas Mental Health University Institute, Montreal Canada H4H 1R3.

gSTOP-AD Centre, Montreal Canada, Montreal Canada H4H 1R3.

hMcGill University, Montreal Canada H3A 0G4.

iMcConnell Brain Imaging Centre, Montreal Neurological Institute, Montreal Canada H3A 2B4.

kJohn Hopkins University, Baltimore USA MD 21,218.

c Centre de Recherche de l’Institut Universitaire de Gériatrie de Montréal, 4545 Queen Mary Rd, Montréal Canada H3W 1W6.

mUniversity of Montreal, Montreal Canada H3T 1J4.

oNorthwestern Univeristy, Evanston, USA, IL 60,208.

nAlzheimer’s Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam Netherlands 1081.

Funding

This work was supported by: Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Pre-symptomatic Evaluation of Novel or Experimental Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease (PREVENT-AD) program data release 6.0. PREVENT-AD was launched in 2011 as a $13.5 million, 7-year public–private partnership using funds provided by McGill University, the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQ-S), an unrestricted research grant from Pfizer Canada, the Levesque Foundation, the Douglas Hospital Research Centre and Foundation, the Government of Canada, and the Canada Fund for Innovation. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Development Office of the McGill University Faculty of Medicine and by the Douglas Hospital Research Centre Foundation (http://www.douglas.qc.ca/). Alzheimer’s Association Research grant (SV), project grant through Canadian Institutes of Health Research (SV); Henry J.M. Barnett Heart and Stroke Foundation New Investigator Award (CJG), Michal and Renata Hornstein Chair in Cardiovascular Imaging (CJG); Mirella and Lino Saputo Research Chair in Cardiovascular Health and the Prevention of Cognitive Decline from the Universite de Montreal at the Montreal Heart Institute (LB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Intzandt, B., Sanami, S., Huck, J. et al. Sex-specific relationships between obesity, physical activity, and gray and white matter volume in cognitively unimpaired older adults. GeroScience 45, 1869–1888 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00734-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00734-4