Abstract

The social capital that employees form on international assignments can have important implications for organizational outcomes. However, despite valuable prior research efforts, how and under which conditions international employees’ social capital is formed and translated into benefits for individuals and organizations remains unclear. To address this shortcoming, we employ a systematic literature review methodology and analyze papers on social capital in international careers published in peer-reviewed journals between 1973 and 2022. We integrate our findings into a framework that depicts the micro-, meso-, and macrolevel antecedents that influence the formation of social capital and describe the functional and dimensional features constituting international employees’ (IEs’) social capital. Our review thus outlines how IEs’ social capital is translated into individual and organizational outcomes as well as how it is contingent on several conditions. Based on our proposed framework, we conclude this paper with several suggestions for future research as well as certain practical suggestions for organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

International employees’ (IEs’) social capital, defined as their social network and the potential resources they may access through that network (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998), is indispensable for multinational corporations. With their global social contacts, IEs build bridges of communication (e.g., Boyle et al. 2016; Harvey et al. 2011; Shimoda 2013) and are the social glue in trustful collaborations (e.g., Furusawa and Brewster 2018, 2019; Miesing et al. 2007) that cross cultural, geographical and functional boundaries. In addition, IEs’ social capital is associated with several personal benefits, e.g., foreign adjustment (e.g., Ang and Tan 2016; Chiu et al. 2009), job performance (e.g., Shen and Hall 2009; van Bakel et al. 2016, 2017) and career advancement (e.g., Cooke et al. 2013; Shortland 2011).

Despite considerable growth in the literature on IEs’ social capital in recent decades, to date, only a limited effort has been made to integrate the extant findings, and even this effort is not without limitations. For example, conceptual papers have mainly focused on a few antecedents or outcomes relating to social capital from either the individual (Farh et al. 2010; Mao and Shen 2015; Shen and Hall 2009; van der Laken et al. 2016; Laken et al. 2019) or organizational perspectives (Crowne 2009; Miesing et al. 2007; Schewe and Nienaber 2011), paying little attention to other variables that may also affect social capital formation and leveraging. Similarly, other studies have reviewed the multilevel outcomes of IEs’ interactions with host country nationals but have neglected other IE social networks (van Bakel 2019). Although there are other relevant reviews on social capital in diverse management research fields, such as international joint ventures (e.g., Zhao and Castka 2021), entrepreneurship (e.g., Gedajlovic et al. 2013), or buyer-supplier relationships (e.g., Alghababsheh and Gallear 2020), these reviews concern social capital in contexts that are different from the IE context.

Consequently, several reasons underly the urgent need for a systematic integration of findings related to the topic of IEs’ social capital. First, little research has systematically analyzed and synthesized the existing knowledge on how and under which conditions IEs’ social capital is formed and translated into individual and organizational outcomes. This is problematic, given the growing evidence for the poor recognition of IEs’ international experience and social capital by their home country employers (e.g., Aldossari and Robertson 2016; Kraimer et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2017). Moreover, diverse available IE definitions and numerous conceptualizations of social capital have contributed to the scattering of knowledge. For instance, IEs’ international trajectories vary greatly from one sample to another (Harrison et al. 2004; Harvey et al. 1999; Suutari and Brewster 2000), and different taxonomies are employed in their definition (Shaffer et al. 2012). IEs working abroad on their own initiative or for an indefinite period may be more motivated to establish local contacts than others who work abroad at their company’s behest with an envisaged return home (Tharenou and Caulfield 2010). Finally, studies have employed diverse social capital conceptualizations, making it difficult to compare their results and extract overarching themes. While some studies employ a social network perspective (e.g., network size, the strength and frequency of contacts; (e.g., Agha-Alikhani 2016; van Bakel et al. 2016), others focus on the type of social support provided to IEs (e.g., Harrison and Michailova 2012; Sterle et al. 2018).

We therefore address the shortcomings of this prior research by adopting a systematic literature research methodology. We integrate all the examined antecedents (at the micro-, meso-, and macrolevels), conditions, and outcomes of IEs’ social capital into a much-needed cohesive framework to explain how IEs’ social capital is formed and leveraged at both the individual and organizational levels. Specifically, we focus on answering the following questions:

-

i.

How is the social capital of international employees formed?

-

ii.

How and under which conditions is IEs’ social capital translated into individual and organizational outcomes?

Our contribution to the extant literature is thus threefold. First, based on our systematic literature review, we present a framework that integrates all the studies on IEs’ social capital to capture an overarching picture of the formation and leveraging of social capital in the international career context. Second, we focus on the antecedents (at the micro-, meso-, and macrolevels) that contribute to how IEs’ social capital is formed. Finally, we explore the conditions under which social capital is translated into individual and organizational outcomes. Accordingly, we provide a holistic overview, mapping the current state of the field while presenting valuable propositions for future research. Hence, our study not only provides a better understanding of IEs’ social capital but also enables individuals and organizations to better reap benefits from IEs’ formed social capital.

2 A theoretical background: the social capital of IEs

In this paper, we adopt a broad definition of IEs, as this allows us to conduct a broad review of the literature on social capital in international careers. Following De Cieri and Lazarova (2020), we define IEs as employees performing ‘international work’. This comprises work across national borders by global project teams, international business travelers, and temporary or permanent work relocations. We therefore account for a missing clarity regarding the construct of IEs and a continuous emergence of new types of IEs, which may exacerbate the theoretical challenge of defining IEs (e.g., Levy et al. 2019; McNulty and Brewster 2016; Zikic et al. 2010). However, a minimum consensus has been reached thus far; scholars agree that only an overarching definition of international mobility, accounting for the manifold types of IEs, can avoid the eventual shortcomings of mobility diversity in international HRM (Briscoe and Schuler 2004; Collings et al. 2007; Tharenou 2015). We reckon this in our review by considering the possible differences and similarities that different IE types may demonstrate in the creation and leverage of their social capital.

During their international assignments, IEs make new contacts abroad and, through the resources and advantages of this social capital (Bourdieu 1985), foster their own and their employers’ benefits (e.g., Doherty and Dickmann 2009; Reiche et al. 2009; Welch et al. 2009). Their social capital comprises a network of social relationships in which IEs’ interactions are guided by perceptions of trust, norms, and sanctions (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998; Putnam 1993, 2000). As value systems vary across cultures and countries (Fukuyama 1995), the ways in which IEs build and maintain relationships are affected by their host country’s culture (e.g., Furusawa et al. 2016; Urzelai and Puig 2019).

IEs’ social capital is fundamentally distinct from that of other groups of workers. Compared to domestic workers, the processes of IEs’ social capital formation and leveraging are fundamentally different. Any IEs’ foreign stay is temporal in nature and implies maintaining social networks across geographical and cultural boundaries even after returning to their home country. While domestic workers might have easier conditions for establishing long-lasting relationships and thus stable social capital, IEs encounter more difficulties in building (through cultural distance) and maintaining (through the temporality of international stay) relationships and thus in their access to resources. IEs often operate in host country cultures where they must learn to navigate local informal networks that are infused with distinct cultural norms and values which differ from their home country networks in how relationships are built, maintained, and utilized (Minbaeva et al. 2022). Furthermore, IEs distinguish themselves from other international workers in terms of the outcomes associated with their social capital. For instance, while social capital outcomes such as innovation and profitability might be important success indicators for international entrepreneurs, they differ from the success indicators for IEs, such as (re-)integration, job performance, or knowledge transfer (e.g., Brewster et al. 2014).

Therefore, in this study, we adopt a social capital definition that accounts for not only the structural and relational aspects of social capital but also the cognitive factors (e.g., the value systems of IEs’ host countries) that likely affect the formation and leveraging of social capital in international careers (Bruning et al. 2012; Taylor 2011; Zhang and Peltokorpi 2016). We follow Nahapiet’s and Ghoshal’s (1998) approach, distinguishing among structural social capital (network ties, network configurations, and appropriable organizations of relationships), cognitive social capital (shared codes and language among relationships), and relational social capital (indicating the quality of relationships regarding trust, obligations, and respect). We further define social capital as “the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or social unit” (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998, p. 243). Many other studies on social capital in international careers have applied this definition (e.g., Bozkurt and Mohr 2011; Fitzsimmons et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2018).

3 Methodology

To identify the relevant studies, we employ the systematic review methodology of Tranfield et al. (2003). The utility of this approach extends from its predefined algorithm, by which extant research’s relevance to the purpose of this paper is evaluated. Our objective for conducting this review is intentionally broad and somewhat standard for similarly comprehensive reviews: to assess the range of definitional, conceptual, operational, and theoretical similarities and differences in this research domain. Considering other systematic review structures (Post et al. 2020; Short 2009; Siddaway et al. 2019; Webster and Watson 2002), the following section presents our data collection and data analysis with a coding scheme and then reports our results.

3.1 Data collection

Our first boundary for finding relevant studies was established by defining the review period. Our focus is on the literature concerning social capital with an expatriation context in MNCs published between 1973 and September 2022. This period is justified by Granovetter’s (1973) first highly important contribution to social capital theory and its implications for individuals. In our literature sample, we consider only articles from peer-reviewed journals to ensure that our review builds on validated and impactful research (Podsakoff et al. 2005). The ISI Web of Knowledge’s Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) database was chosen as the database of record because it is one of the most comprehensive databases of peer-reviewed journals in the social sciences.

To identify all the articles related to social capital theory, we included a variety of search terms: ‘Social capital’, ‘Bridging bonding’, ‘Bridging social capital’, ‘Bonding social capital’, ‘Network*’, ‘Social Ties’, ‘Weak ties’, ‘Strong ties’, ‘Linking social capital’, ‘Career capital’ and ‘Knowing whom’. The same applies to the second conceptual boundary condition by which we defined the following synonyms: the search terms ‘International employee’, International mobility’, ‘International career’, ‘International companies’, ‘International organization’, ‘International manage*’, ‘Expat*’, ‘Migra*’, ‘International*’, ‘International business’, ‘International assignees’, ‘Assign*’, ‘Global Career’, and ‘Global mobility’. These were queried in quotes, as shown, to avoid irrelevant topics as needed. Using a traditional Boolean search approach, we combined the first conceptual boundary term with the second in all possible combinations.

The third search boundary was determined by our chosen database, as our search was conducted exclusively on the ISI Web of Knowledge. When a search term combination resulted in more than 500 articles, we applied the ‘Management’ Web of Science category filter. Any journals and their respective articles in the Web of Science core collection are assigned to different categories. The category assigned to an article depends on several criteria, for instance, the subject matter and scope of the journal in which it is published, its author and editorial board affiliations, and its cited references. Before applying the management category filter in our review process, we tested its functionality once and compared our filtered results to the unfiltered results to ensure that we would not omit any relevant publications. However, as we found no relevant omitted results when applying the management filter, we opted for filtering only when a search exceeded 500 results. Given the large number of results we reviewed, this also contributed to the thoroughness of our review process. Additionally, addressing the rigidity of our systematic review process, we conducted an independent search on Google Scholar and performed a cross-reference check during our final article selection. In this way, we avoided omitting any major contributions and verified our results. The whole review process is summarized in Fig. 1.

3.2 Data analysis

The initial search process yielded 1,436 papers. In the first step, all articles were examined for their relevance by reviewing their titles and keywords. Papers were considered for inclusion only if their keywords and/or title indicated a contribution to the knowledge on IEs’ social capital. This literature review focused solely on IEs’ social capital in an organizational context. Many papers have dealt with social capital; however, organizational context was missing. These excluded papers have addressed, among other topics, the social capital of local communities, international development projects, or international relations at the national level. After this exclusion, a final base of 254 articles remained. In the second step, we checked the articles’ abstracts. The articles that were excluded from further analysis focused, for instance, not on individual social capital but rather on capital as an asset of a whole organizational unit, a team, or an entrepreneur, without any linkage to individual social capital. Additionally, any papers that were merely concerned with the role of social capital in the academic environment or with students’ social capital were not included for further analysis due to their context differing from that of typical MNEs. Additionally, no articles that analyzed the outcomes of individuals’ social capital for a community were considered; similarly, conference papers, specifically descriptive papers and editorials, were excluded. Finally, our final sample thus included 153 articles that examine the social capital of IEs as an antecedent, moderator, mediator, or outcome relevant to their individual careers or with organizational implications.

The preliminary scheme with which we commenced coding the articles included the following: research method, number of interviewees, social capital theory, IE type (if defined), gender, industry in which interviewees are embedded, host country, and home country. During the review process, we extended this scheme by categorizing the articles’ findings into antecedents, moderators, mediators or outcomes of social capital. To ensure that we did not omit any important information, we repeated article coding several times. Our final thematic codes were as follows: (1) name(s) of the author(s), (2) year of publication, (3) journal title, (4) sample (number and type of IE and demographic information), (5) employed social capital definition, (6) antecedents, (7) moderators, (8) mediators, (9) outcomes, and (10) research method. While reviewing our literature sample, we noted that scholars have not only analyzed how IEs’ social capital was formed and translated into individual and organizational outcomes but also explored the interactions of variables in the same category. For example, some articles have unraveled the relationships between individual and organizational outcomes of IEs’ social capital or studied the interactions of individual outcomes with each other. However, in this review, we do not report any processes occurring among individual and organizational outcomes. Our focus is on the formation and translation of IEs’ social capital, not on how the outcomes of social capital are entangled. Therefore, in this review, we focus only on how IEs’ social capital is directly translated into outcomes, not on how distinct outcomes may interact with each other. An overview of all the analyzed articles and the key findings that are relevant to our review’s purpose is provided in the appendix of our study.

4 Findings

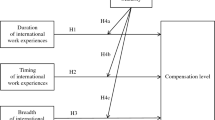

Our analysis included a total of 153 articles, of which 125 were empirical and 28 were conceptual. Most of the reviewed empirical articles employ a quantitative research design (N = 70). The remaining papers use qualitative designs (N = 46), mixed method approaches (N = 5), or case studies (N = 4). To present our findings below, we begin by presenting the literature that explores how IEs’ social capital is formed. This section comprises two parts: first, the different micro-, meso- and macrolevel antecedents that determine how IEs’ social capital is formed; second, the dimensional and functional features constituting IEs’ social capital. Next, we turn to the literature that corresponds to our second research question regarding how the antecedents and processes of IEs’ social capital relate to individual and organizational outcomes. This section thus comprises the literature that illustrates how IEs’ social capital can lead to individual outcomes and to organizational outcomes. Finally, we identify certain factors in the literature, the translating conditions, which may foster or diminish the translation of IE social capital into individual and organizational outcomes. Figure 2 shows an integrative framework that summarizes our findings on the various antecedents, features, conditions, and outcomes of IEs’ social capital.

4.1 Antecedents of IE’s social capital formation

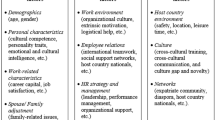

In our review, we have identified several factors influencing the formation of social capital. To provide a holistic and structured presentation, we organize our findings at the micro, meso and macro levels. At the micro level, we summarize the studies dealing with the individual characteristics and traits as well as the motivations and behaviors influencing the formation of social capital. At the meso level, scholars have related job and organizational characteristics to IEs’ social capital. Finally, at the macro level, the influence of national and cultural aspects on IEs’ social capital has been studied.

4.1.1 Microlevel antecedents forming IEs’ social capital

Individual characteristics and traits. First, some research in our literature sample has explored how certain individual characteristics and traits that rarely change across time and different contexts are related to the formation of IEs’ social capital. Studies in this category are concerned with IEs’ demographics and various forms of individual intelligence, identity, and personality. Although many empirical studies document IEs’ demographics such as gender, age, marital status, origin, or education (e.g., Agha-Alikhani 2016; Baughn et al. 2011; Bruning et al. 2012; Chiu et al. 2009; Levy et al. 2015), few relate demographic antecedents to the creation of IEs’ social capital. As such, female and homosexual IEs have been found to represent a minority of IEs, which may hinder IEs’ integration and impede their construction of social networks (e.g., Harrison and Michailova 2012; McPhail and Fisher 2015; McPhail et al. 2016). Furthermore, the social obligations arising from strong relationships (e.g., with family members) have been found to influence women’s decision to relocate more often than men’s (Lauring and Selmer 2010; Lindsay et al. 2019). Although the disparate demographic backgrounds of IEs and their host country colleagues may raise barriers in their social interactions, Lee (2010) has shown that these can be overcome through IEs’ intellectual, emotional and cultural intelligence, which can help them build a social support network abroad. Additionally, host country knowledge and cultural intelligence assist IEs in developing culturally diverse networks (e.g., Ang and Tan 2016; Elkington et al. 2017; Fitzsimmons et al. 2017). Other factors related to people’s mental capacity, favoring the construction of local social capital, are cultural empathy (van Oudenhoven et al. 2003), self-appraisal and emotional stability (Chiu et al. 2009), and eloquence and language skills (Elkington et al. 2017; Furusawa and Brewster 2019). IEs’ expertise in their host country has no effect on their interaction frequency with host country nationals (Kubovcikova and van Bakel 2022). In contrast, significantly more attention has been given to determining what personality traits promote IEs’ social capital. Among them are learning-goal orientation (Farh et al. 2010), extraversion (Bruning et al. 2012; Chiu et al. 2009), cultural humility (Caligiuri et al. 2016), cosmopolitan ability and international experience (Levy et al. 2021), English language competency (Peltokorpi 2022), core-self-evaluation (Johnson et al. 2003; Rodrigues et al. 2019) and open-mindedness (van Bakel et al. 2016). Interestingly, while much of this research has been concerned with identifying the factors that contribute to IEs’ social capital formation, few studies have paid attention to how these antecedents lead to IEs’ social capital. For instance, Andresen et al. (2018a) and Bader (2015) have found that IEs with a strong sensitivity to uncertainty (caused by, e.g., terrorism in the host country) rely more on strong social relationships.

In sum, some IEs may be more likely to build social capital than others due to their demographics, intelligence, personality, or identity, but how such different factors specifically contribute to diverse forms of relationships and resource leverage remains unclear.

Identities, motivations, and behaviors. As individuals are motivated to act in congruence with their sense of self (Ashforth et al. 2007), in this category, we summarize the research on how individuals’ identities, motivations, and behaviors relate to their formation of social capital. Studies have shown that a multicultural identity facilitates relationship building in a host country (Chiu et al. 2009; Furusawa and Brewster 2019; Selmer 2001) and that IEs with a strong focus on social relations and their contribution to social groups tend to have better relationships with host country nationals (Jannesari et al. 2016). Other forms of identity, such as social or relational identity, have thus far not been a research focus in terms of IEs’ social capital. However, studies show that IEs’ motivation is an important antecedent for acquiring cross-cultural networks (Richardson and McKenna 2014; van der Laken et al. 2016) and that IEs’ motivation for building foreign social contacts varies by assignment type (Agha-Alikhani 2016) and career orientation (Welch et al. 2009; Zikic et al. 2010; Farh et al. 2010) have also proposed that support-seeking IEs are expected to acquire networks more easily than those with little motivation. Thus, individuals who understand themselves to be part of several cultures and are open to building new social relations are more likely to form social capital abroad than those who are focused merely on their home country career.

4.1.2 Mesolevel antecedents forming IEs’ social capital

Job factors. Regarding job factors, we have identified studies that analyze how different types of IEs and their job functions abroad relate to their acquisition of individual social capital. First, concerning the former, we observe that the types of IEs analyzed in the literature vary and that scholars have not used a consistent definition for them. The types of IEs analyzed in prior research have most often been simply mentioned, without any further classification. Other papers have focused on specific types of IEs such as expatriates (e.g., Manev and Stevenson 2001; Mao and Shen 2015); self-initiated expatriates (e.g., Agha-Alikhani 2016; Cao et al. 2014; Dickmann et al. 2018); IEs returning home, called repatriates (e.g., Aldossari and Robertson 2016; Kimber 2019; Reiche 2012); IEs brought from a foreign subsidiary to headquarters, called inpatriates (Reiche 2011; Reiche et al. 2011); company-assigned expatriates (Agha-Alikhani 2016; Jokinen et al. 2008; Leiva et al. 2018); or high-skilled migrants (e.g., Colakoglu et al. 2018; Cooke et al. 2013; Moore 2016). Additionally, studies differ in terms of the characteristics of IEs’ assignments that they address. In particular, the length of an assignment and its underlying contract design with regard to the organization lead to variations in IEs’ personal willingness to build cross-cultural ties (Mao and Shen 2015; van der Laken et al. 2016). Company-assigned expatriates, for instance, feel encouraged to maintain their home-country contacts (Mäkelä and Brewster 2009) because their return to their home country is already determined, entailing their decreased interest in host-country contacts (e.g., Cao et al. 2014; Levy et al. 2015; Mao and Shen 2015). In contrast, self-initiated expatriates show agency in their acquisition of supporting host country contacts, improving their job performance (Pinto and Araújo 2016), and acquire broad and diverse networks with contacts worldwide (Agha-Alikhani 2016). Furthermore, regarding IEs’ job functions, boundary spanning, job autonomy, and functional similarity have been shown to play a role in the creation of social capital. For IEs interacting in heterogeneous environments across diverse borders and functions, job mobility and boundary-spanning roles have been shown to foster the creation of social capital (e.g., Baughn et al. 2011; Levy et al. 2019; Sapouna et al. 2016). A similar effect is reported for job autonomy, which allows IEs to expand their instrumental ties with their host country contacts (Chiu et al. 2009; Lakshman and Lakshman 2017), whereas building strong ties is fostered through functional similarity and high operational relatedness (Baughn et al. 2011; Mäkelä et al. 2012a). Overall, then, this section has shown that IEs have different opportunities to form social capital due to the distinct designs of their assignments and jobs.

Organizational factors. Studies in our sample that address organizational factors are mostly concerned with several support measures that influence the formation of IEs’ social capital, such as hard and soft skill training (Baughn et al. 2011), predeparture training (Beutell et al. 2017), cross-cultural training (Harrison and Michailova 2012), organizational relocation support (Mao and Shen 2015), formal mentoring (Shen and Kram 2011), and global leadership development programs (Moeller et al. 2016; Stensaker and Gooderham 2015). It has been frequently stated that organizational support measures are vital to IEs’ assignment success (e.g., Cao et al. 2014; Miao et al. 2011; Oparaocha 2016) and that perceived organizational support varies among expatriate types (e.g., Chen and Shaffer 2017; David et al. 2019; McPhail et al. 2016). However, research has also shown that generalized cross-cultural training is redundant for building local social capital due to IEs’ disparate understandings of local cultural and social values (Guo et al. 2021). Furthermore, organizational support may hinder IEs from developing ties with host country nationals (Mao and Shen 2015). This argument has been confirmed in a study showing that headquarters’ management control systems become less important when a subsidiary operates highly autonomously and can rely on its employees’ social capital (Egbe et al. 2018). In the same vein, other scholars have substantiated this knowledge in terms of the importance of trust and shared cognitive grounds (Mäkelä and Brewster 2009) and have pointed to the importance of subsidiary employees’ willingness and capability to share knowledge with coworkers from other organizational units (Mao and Shen 2015; Miesing et al. 2007; van der Laken et al. 2016). As such, while most research has focused on how to support IEs in boundary-crossing social interactions, little attention has been given to how IEs’ interaction partners can be better enabled to contribute to the formation of IEs’ social capital (e.g., host country nationals). Nevertheless, IEs clearly depend on host country nationals’ information and collaboration (Dickmann and Baruch 2011; Doherty et al. 2013). Some research has shown that how host country nationals perceive IEs (e.g., perceived reciprocity, openness and empathy toward IEs) influences how IEs access information and create relationships with their foreign coworkers (e.g., Ng et al. 2015; Toh and DeNisi 2005; Varma et al. 2011). However, no study in our sample analyzes how host country nationals can be supported to help IEs form their social capital.

The literature presented in this section thus clearly shows that organizational support plays an important role in the formation of IEs’ social capital. For instance, a well-balanced support program critically enables IEs to succeed in their assignments abroad and fosters social interactions between IEs and host country nationals, favoring the formation of IEs’ social capital.

4.1.3 Macrolevel antecedents forming IEs’ social capital

Cultural factors. Articles in our sample integrating macrolevel factors study how national and cultural factors affect IEs’ social capital creation. Several studies have considered the cultural differences between IEs’ home and host countries in relation to social capital (e.g., Baughn et al. 2011; Cao et al. 2014; Harvey et al. 2011; Ramström 2008). For instance, when IEs and host country nationals perceive each other to be highly dissimilar, this results in low-trust relationships (Harvey et al. 2011). Similarly, host country nationals’ willingness to connect with and support IEs depends on cultural factors such as perceived similarity, ethnocentrism and collectivism (Furusawa and Brewster 2019; Varma et al. 2011, 2012, 2016). Additionally, Wang and Nayir (2006) demonstrate that European IEs in China have built closer and more gender-diverse but less culturally diverse networks than IEs in Turkey. Moreover, Chinese IEs develop only limited social capital abroad because they place greater importance on their home country networks (Yao et al. 2015). Only recently have scholars started paying greater attention to the influence of local culture and forms of informal networks on IEs’ social capital formation, calling for more research on the influence of informal networks on IEs’ professional and private lives (Horak and Paik 2022). Thus, their host and home country cultures clearly influence how IEs form their social capital. While dissimilarities may be a hindrance at the beginning of an international assignment, IEs are likely to culturally adapt abroad, likely increasing the trust between host country nationals and IEs over time (Harvey et al. 2011).

National factors. Some studies have also identified certain national factors that influence IEs’ social capital formation. National legislation raises probable barriers for IEs who belong to a minority group (e.g., ethnic origin, gender, or sexual orientation) (Caligiuri and Lazarova 2002; McPhail et al. 2016; Rodriguez and Scurry 2014). Furthermore, hostility, defined as the specific host country conditions that challenge IEs’ work and live (e.g., through political instability), have been an intensively discussed topic in the context of international careers (Gannon and Paraskevas 2019). Notably, studies in our sample have shown that social support and networks are more important for IEs living in terrorism-endangered countries (Bader 2015; Bader and Berg 2014; Bader and Schuster 2015). Dickmann and Watson (2017) have also found that IEs rely more on social support when they are assigned to hostile environments, such as terrorism-endangered countries. However, scholars have also argued that terrorism may hinder IEs from establishing trustful relationships with host country nationals and that individuals’ safety concerns can create conflicts between IEs and their accompanying family members (Bader and Berg 2014). Other national conditions that may affect the formation of IEs’ social capital, such as war or limited facilities in developing economies, have not yet been studied. Nevertheless, the available knowledge allows us to conclude that organizations should be aware of any country-specific national factors that may affect individuals in their day-to-day interactions with host country nationals.

4.2 Dimensional and functional features of IEs’ social capital

A main issue we have encountered in our review of the selected articles is that researchers employ diverse definitions to conceptualize and operationalize social capital. This lack of conceptual clarity impedes our summary of the existing knowledge and structural representation of our findings. We have therefore looked for other ways to organize our findings and have recognized that the literature is characterized by two distinct features of social capital. That is, scholars have either tended to focus on the dimensional or functional features of social capital. Articles on the former, the dimensional features, analyze the potential operability of social capital by studying the various features that are inherent to individuals’ networks of relationships and through which IEs may access social resources. We have categorized these dimensional features into structural, relational or cognitive dimensions according to Nahapiet and Ghoshal’s (1998) definition of social capital. Concerning the latter, articles focusing on the functional features are primarily concerned with the actual functionality of social capital, showing which social resources are actually accessed in IEs’ social networks. We have thus further organized our findings on the functional features of social capital based on emotional, informational or instrumental support (Thoits 1985).

4.2.1 Dimensional features of IEs’ social capital

Structural network dimension. First, we present the articles in our sample that are concerned with how IEs’ networks are configured. Articles in this category often analyze structural network characteristics such as IEs’ embeddedness, network size, density, tie strength, or diversity and employ a variety of measurement methods. For example, several quantitative studies (e.g., Au and Fukuda 2002; Bader and Schuster 2015; Cao et al. 2014) have adopted disparate forms of network analysis (e.g., Burt 2000; Lincoln and Miller 1979; Michie and Burt 1994; Seibert et al. 2001), applied Williams’s (2006) bonding and bridging social capital scale (e.g., Andresen et al. 2018b) or tested IEs’ embeddedness (e.g., Chen and Shaffer 2017) according to Crossley et al. (2007). Such studies also vary in terms of their loci regarding social networks. For example, scholars have analyzed IEs’ friendship and support (e.g., Bader and Schuster 2015; Wang and Nayir 2006), work advice (e.g., Au and Fukuda 2002), and community networks (e.g., Chen and Shaffer 2017). The structural approaches in these studies thus allows us to better understand why some IEs more easily adjust to foreign environments than others and to detect beneficial positions in social structures. For example, networks of self-initiated employees differ from those of company-assigned employees in size and diversity (Agha-Alikhani 2016). Furthermore, IEs who have diverse social networks with ties to various cultures and social systems (e.g., company colleagues, friends, colleagues from other companies) become better adjusted and embedded in their host country (Mao and Shen 2015; Shen and Kram 2011). However, IEs typically interact more frequently with other IEs than host country nationals (Kubovcikova and van Bakel 2022). Additionally, IEs’ intention to stay in their host country is weaker when they have large home country networks, while IEs with both national- and international-focused networks gradually weaken their ties to their home country if the provided support functions in their host country are sufficient (Cao et al. 2014).

Further research has shown that IEs’ organizational embeddedness is positively related to their retention (Reiche et al. 2011) and an improved person-organization fit. Pustovit (2020) has also found that host country network embeddedness contributes to work adjustment and an effective understanding of work requirements and norms. In terms of tie strength, strong ties decrease IEs’ turnover intention and perceived stress (Andresen et al. 2018b; Lauring and Selmer 2010), whereas weak ties provide greater access to more diverse knowledge (Richardson and McKenna 2014), faster access to more tacit knowledge (Mäkelä et al. 2012a; Mors 2010) and greater diversity in extra-organizational mentoring ties (Shen and Kram 2011). For IEs commencing an international assignment, culturally diverse networks might be particularly important, as they facilitate host country integration (Van Gorp et al. 2017a) and improve psychological well-being (Wang and Kanungo 2004). Repatriating IEs, however, benefit more from their home country than host country networks (Van Gorp et al. 2017a; Gorp et al. 2017b). A few studies have also evaluated IEs’ online social capital resulting from their social media engagement, showing that online contact positively influences IEs’ well-being (Fischlmayr and Kollinger 2010), career advancement (Linehan and Scullion 2008; Mooney et al. 2016), knowledge transfer and retention (Crowne 2009).

Thus, the structural dimension of IEs’ social capital plays a critical role in the process of forming and leveraging social capital. Research has explored several kinds of networks and relationships that comprise IEs’ social capital resources: IEs’ social ties abroad must be sufficiently strong to benefit IEs’ adjustment and assignment completion, and IEs need many weak ties in their host country for effective intraorganizational knowledge transfer. Meanwhile, IEs should not neglect their home country networks, which may facilitate their return home.

Cognitive network dimension. Furthermore, the articles exploring how a shared cognitive ground influences the creation of social capital concern the cognitive network dimension of social capital. Such research builds on the principle of homophily, according to which relationships are built through perceived common characteristics among individuals (e.g., Burt 1992, 2000; McPherson et al. 2001). Indeed, cultural identity (Mäkelä et al. 2012a) and shared international experience (Van Gorp et al. 2017a) are beneficial to relationship building, with positive consequences for IEs’ psychological well-being (He et al. 2019) and organizational knowledge transfer (e.g., Ismail et al. 2016, 2019; Jannesari et al. 2016). As such, while shared cognitive grounds help build social capital, distinct cognitive grounds hinder its construction. Other research has shown that IEs’ social networks are shaped by cultural factors and that IEs can switch among distinct cultural frames depending on their interaction context (Richardson 2021; Ulusemre and Fang 2022) have identified two ways through which IEs utilize of guanxi and their local informal networks in China; the defensive use of guanxi is morally acceptable and help IEs stay or enter their local market, while the competitive use of guanxi is considered immoral yet allows them to strive in their market and gain advantages over others. In contrast, cultural dissimilarity impedes IEs’ accumulation of social capital (Yao 2014), whereby IEs’ acquired social networks differ in size, cultural diversity, localization, closeness or frequency depending on their origin (Wang and Kanungo 2004). However, Mao and Shen (2015) suggest that perceived dissimilarities diminish over time as IEs adapt their cultural identity, which may result in a change in their network diversity. The literature presented in this section therefore allows us to understand that IEs’ social capital is formed based on commonality perceptions, such as culture and shared international experience. However, the relevant research is rather limited, and other commonality perceptions may also play a role in the accumulation of IEs’ social capital.

Relational network dimension. The final dimensional feature of IEs’ social capital points to the role of trust, as a quality parameter, in IEs’ relationships (e.g., Ang and Tan 2016; Egbe et al. 2018; Harvey et al. 2011). Scholars have distinguished between affective and competence-based trust and whether how either is built relates to the time that IEs spend abroad. For example, IEs in long-term assignments develop affective trust rather than competence-based trust with their host country colleagues. Conversely, as short-term IEs have less time to build strong ties, their trust remains at the more superficial, competence-based level (Harvey et al. 2011). However, for IEs spending only a little time abroad, their initial interactions in non- or semibusiness-related environments foster the development of trustful relationships. Such knowledge is particularly important for IEs operating in countries where trust is considered a prerequisite for the successful operation of business, such as China (Baughn et al. 2011). Affective trust relates positively to organizational knowledge sharing (Lee et al. 2021). Furthermore, trust has been associated with positive outcomes, e.g., fostering IEs’ adjustment (Ang and Tan 2016; van Bakel et al. 2016) while promoting subsidiary control, boundary spanning and knowledge transfer through trustful relationships among host country nationals, IEs and headquarters (Egbe et al. 2018; Furusawa and Brewster 2018; Ismail 2015). Hence, we conclude that trust is an important indicator of IEs’ social capital; while it usually takes time to build affective trust, competence-based trust can be established rather quickly. Some research also indicates that trust is a function of not only the time but also the context in which social interactions take place. As such, semi- or nonbusiness environments help build trust in early relationship building.

4.2.2 Functional features of IEs’ social capital

Informational support. Under informational support, we categorize all the articles dealing with support in the form of the guidance or advice that is provided to IEs to facilitate their daily lives (Caligiuri and Lazarova 2002; Thoits 1985). Informational support providers include host country nationals and headquarters personnel (Agha-Alikhani 2016; Egbe et al. 2018; van Bakel et al. 2017) or friends (Shen and Kram 2011). Serving a double function as colleagues that are also friends, they have been found to not only provide information about organizational practices and habits but also to be important for IEs’ adjustment because informational support providers invite IEs to local events and serve as a bridge to their own personal network (Caligiuri and Lazarova 2002; Pinto and Araújo 2016; Sterle et al. 2018). In contrast to emotional support, work information support has been shown to be less dependent on interaction frequency (Kubovcikova and van Bakel 2022), likely rendering it more accessible for IEs. Accessing informational support may be particularly important for IEs who are beginning their international assignment when they have little familiarity with their host country and for those where little organizational support is available (Farh et al. 2010). Thus, guidance and advice from host country coworkers can have a significant influence on social capital formation. Particularly at the start of IEs’ assignments, host country nationals should be aware of their role in how IEs adjust to their foreign culture.

Instrumental support. Scholars have also explored how instrumental support, e.g., financial assistance or services, contributes to the formation of IEs’ social capital. Often provided by colleagues and host country nationals, instrumental support assists IEs with, e.g., host country governmental regulations, tax applications, or child care services (Agha-Alikhani 2016; Bruning et al. 2012; Stroppa and Spiess 2010). As this country-specific information is difficult to access as a foreigner, host country nationals are key support providers, facilitating IEs’ daily operations. Scholars have outlined the diverse support roles that IEs’ host country colleagues may assume to help IEs understand their local culture. They may foster communication, transfer information between IEs and host country nationals or provide formal and informal training to host country nationals and IEs (Vance et al. 2009, 2014). However, organizational support measures become more important when instrumental support from friends and colleagues is absent (Caligiuri and Lazarova 2002; Stroppa and Spiess 2010; van der Laken et al. 2016). Instrumental support enables IEs’ embeddedness and adjustment (Sterle et al. 2018) and cross-cultural transition (Pinto and Araújo 2016) in their host country. Overall, then, host country nationals can smooth IEs’ host country integration through instrumental support. Organizations should thus not only advise and guide IEs but also support local employees in welcoming and interacting with their foreign colleagues.

Emotional support. Some scholars have also explored the role of emotional support, as a social resource, in providing empathy, affection and care to IEs. Relationships providing emotional support have been shown to exchange trust, create a sense of security and belonging (Bayraktar 2019), assist in IEs’ identity formation (Van Gorp et al. 2017a) and offer companionship (van Bakel et al. 2017). Scholars have found that IEs perceive this type of support from their family, friends, and friends at work, as well as host country nationals (e.g., Agha-Alikhani 2016; Shen and Kram 2011; Van Gorp et al. 2017b). However, the ability of others to provide IEs emotional support has been shown to depend on various factors. For example, accompanying spouses are supportive of IEs’ career advancement (Lauring and Selmer 2010), but for family and friends located outside their host country, providing their required emotional support might be more difficult, as they lack sufficient knowledge of this host country (Van Gorp et al. 2017a). Negative international working experiences among IEs’ partners may also cause stress and negatively influence IE retention (Van Gorp et al. 2017a), while family conflicts can harm IEs’ psychological well-being (Leiva et al. 2018). If family or friends do not provide emotional support, host country nationals and peers may become valuable resources for emotional support. For instance, peers who have had similar international experiences are able to share information with IEs and provide emotional support (Shen and Kram 2011; Van Gorp et al. 2017b). Thus, emotional support is an important resource for IEs, but its provision by family and friends is sometimes critical. In the absence of family or friends as emotional support providers, other opportunities within IEs’ social networks should be carefully evaluated. IEs’ identification with and connection to colleagues with similar international experience might provide such an alternative.

4.3 Outcomes of IEs’ social capital

Having discussed the antecedents and dimensional and functional features of social capital, we now turn to the outcomes related to IEs’ social capital. We structure this section based on the individual-level and organizational-level outcomes of social capital. At the individual level, we summarize our findings in the following sections: adjustment, performance and positive workplace behaviors, contentment and well-being, and career-related outcomes. At the organizational level, we discuss relevant articles on IEs’ social capital with regard to organizational performance and knowledge transfer.

4.3.1 Individual outcomes of IEs’ social capital

Adjustment. The comfort and familiarity that IEs perceive with respect to their host country’s culture, their adjustment, is one of the most prevalent topics across all IE research (Takeuchi 2010). Scholars have studied how IEs adjust generally (e.g., Bruning et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2018; Sterle et al. 2018) or have specifically focused on IEs’ work (e.g., Johnson et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2018; Liu 2021; Stroppa and Spiess 2011). Others have also evaluated cross-cultural adjustments (e.g., Harrison and Michailova 2012; Lee 2010; Van Gorp et al. 2017a), adjustment interactions (Liu 2021; Sterle et al. 2018) and psychological adjustments (Van Gorp et al. 2017a; Ward and Kennedy 2001). Such findings indicate that IEs’ social capital is important in their foreign adjustment (e.g., Beutell et al. 2017; David et al. 2019; Dickmann and Watson 2017), and various efforts have been made to identify the central actors in IEs’ social networks who may influence their adjustment. As such, studies have emphasized the role of host country nationals in IEs’ adjustment, as they provide IEs valuable cultural and organizational information (e.g., Farh et al. 2010; Jannesari and Sullivan 2021; Pustovit 2020). Of particular value to IEs is the provision of emotional support that positively affects their perceived level of stress. Close relationships with both host country colleagues and accompanying family members have been identified as driving factors in cross-cultural adjustment (Caligiuri 2000). Concerning the interactions between IEs and host country nationals, we refer to the detailed overview of van Bakel (2019). Other important resources thought to help IEs adjust come from home country family and friends (Caligiuri and Lazarova 2002) and online social networks (Crowne et al. 2015). In fact, Nardon et al. (2015) have found that online blogging aids the cocreation of a social support network, fostering IEs’ adjustment in their host country. Online social networks may not only benefit IEs’ maintenance of their home country network but also promote their acculturation abroad (Hofhuis et al. 2019). Strong ties within their host country facilitate IEs’ adaptation to its foreign culture (e.g., Bruning et al. 2012; Horak and Yang 2016; Nardon et al. 2015); conversely, social support at home helps IEs reintegrate upon their return (Dickmann and Watson 2017). In sum, we find that the literature has identified many important actors in terms of IEs’ adjustment. However, while fostering the interactions of IEs and actors abroad is valuable for understanding IEs’ adjustment, strategically maintaining the interactions of IEs and relevant actors at home is of similar importance for leveraging IEs’ social capital upon their return.

Performance and positive workplace behaviors. The literature concerning how IEs’ social capital contributes to individual performance outcomes and positive workplace behaviors is much more limited. However, such scholars have also primarily focused on identifying the relevant actors in IEs’ social networks. Through improved access to advice, resources and other information required for daily business provided by host country nationals (e.g., Bader and Berg 2014; Bruning et al. 2012; Kraimer et al. 2001), IEs’ job performance can be improved. However, when host country contacts are absent, IEs’ effectiveness may be limited (Horak and Yang 2016). Furthermore, Lee and Kartika (2014) have shown that the relationship between IEs’ social capital and family support with performance is mediated by IEs’ adjustment. Among all the studies in this section, only one focuses on IEs’ innovative work behavior. Specifically, IEs’ contextual knowledge of their host country, obtained through relationships with locals, likely reinforces the relationship between leader-member exchange and IEs’ innovative work behavior (Hussain et al. 2020). Once again, then, these findings point to the role of host country nationals, as important advice and resource providers for IEs, in enhancing IEs’ performance and, when absent, in limiting IEs’ effectiveness.

Contentment and well-being. Another important outcome of IEs’ social capital is that their contentment and well-being abroad relates to their social capital. With their stress-alleviating effects, social bonds have been shown to have positive effects on IEs’ well-being (e.g., Andresen et al. 2018b>; Fu and Charoensukmongkol 2021; Stroppa and Spiess 2010). For example, IEs who are socially supported perceive low stress levels (e.g., Shortland 2018; van der Laken et al. 2016, 2019) and have lower turnover intention (Aldossari and Robertson 2016; Andresen et al. 2018b; Shen and Hall 2009). Specifically, for IEs working remotely abroad, social capital in their headquarters at home has been shown to positively impact their well-being (Apriyanti et al. 2021). Recently, some scholars have also focused on how IEs’ social capital may affect their sense of meaningfulness, suggesting that networking with others may form an important part of their perception of meaningfulness in otherwise fluid and boundaryless work contexts (Ridgway and Kirk 2021). However, scholars have also pointed to the negative effects of IEs’ relationships, particularly those with their emotional support providers (Van Gorp et al. 2017b) and host country nationals (Bader and Berg 2014); these could also be sources of stress due to interpersonal conflicts. Additionally, IEs with diverse social networks have been shown to be more satisfied with their jobs (Au and Fukuda 2002). Overall, IEs’ perceived stress can therefore be relieved through the resources they access within their social networks, which contributes to their well-being; however, the above results also indicate that IEs’ social networks cannot be equated with their perceived support. Emotional support providers can also be a source of stress. Large networks offering opportunities for diversifying resource access are thus helpful for IEs who work and live across various organizational and cultural boundaries.

Career-related outcomes. Although career outcomes may also be partially related to contentment and well-being, we have decided to devote a separate section to IEs’ careers because the career benefits of international assignments are a central topic in IE research. We have summarized the articles dealing with IEs’ career outcomes in both a narrower and a broader sense. First, concerning the former, social networks and their residing resources have often been shown to be beneficial for IEs’ career success (e.g., Haslberger and Brewster 2009); indeed, social capital acquired abroad leads to IEs’ increased job compensation (Schmid and Altfeld 2018). Qualitative research has also indicated the positive effects of having a social network on IEs’ career success (Fischlmayr and Puchmüller 2016; Zikic et al. 2010). However, these results should be interpreted carefully. A quantitative study analyzing the effect of organizational talent management programs on IEs’ social capital and subsequent career success has found a significant relationship only between social capital and subjective career success; there is no support for the effect of IEs’ social capital on their objective career success. With respect to IEs’ relocation success, psycho-social support and cross-cultural transition support have a positive impact (Shen and Kram 2011). We have also found articles dealing with career outcomes in a broader sense. These papers study the effect of IE social capital on career advancement. More specifically, personal support resources (e.g., mentor, family, or spouse) (Colakoglu et al. 2009; Dickmann and Doherty 2008; Furusawa and Brewster 2019; Kirk 2016; Lauring and Selmer 2010) and professional support resources (e.g., expatriate networks or organizational support) (Shortland 2011) are conducive to IEs’ career advancement. However, some studies have also explored the undesirable career outcomes of social capital. For instance, in collectivistic cultures, strong employer expectations of employee loyalty hinder IEs from taking job opportunities outside their company (Aldossari and Robertson 2016). Additionally, such IEs face career advancement difficulties at home because their home country contacts may vanish over time (Mäkelä and Suutari 2009; Schmid and Altfeld 2018; Yao 2014); moreover, these IEs are unlikely to be promoted abroad when their foreign colleagues perceive them as outsiders of the organizational host country network (Rodriguez and Scurry 2014).

In sum, the literature provides valuable insights into the possible benefits and detriments of IE social capital in both host and home countries. While there is little empirical evidence for the effect of IEs’ social capital on their objective career outcomes, such as promotions or salary increases, IEs’ social networks and their internal resources can clearly contribute to their subjective career success and advancement. However, research also indicates that IEs must proactively anticipate challenges upon reentry due to their lost contacts or social expectations in their home country.

4.3.2 Organizational outcomes of IEs’ social capital

Organizational performance. In this section, we focus on articles dealing with the impact of IE social capital on organizational performance. Several studies have shown that IEs’ social capital is conducive to organizational performance. Collaborations of geographically dispersed organizational units may be improved by building social capital among employees, benefiting organizational performance (Baughn et al. 2011; Colakoglu et al. 2014; van Bakel et al. 2017). Through the creation of new business relationships in their host country, IEs can better understand the needs of their host country customers, which in turn increases their firm’s financial performance (Wu et al. 2019; Reiche 2011, 2012) has further found that IEs’ social capital improves knowledge transfer between international employees and their home-country-based colleagues. Moreover, IEs’ social capital in an organizational unit not only facilitates interpersonal actions but may also replace hierarchical conservative control mechanisms. Indeed, a positive relationship exists between global staffing strategies and organizational creative performance, which can be explained by the social networks of newly incoming employees (Shipilov et al. 2017). Thus, organizations clearly benefit from IEs’ social capital both internally and externally through IEs’ improved host country understanding. In particular, IEs channel information flows between their host and home countries, thus contributing to increased knowledge transfer and organizational financial performance and perhaps even replacing other management control mechanisms.

Knowledge transfer. In comparison to the rather small body of knowledge on IEs’ social capital and organizational performance, many studies have examined IEs’ social capital in relation to organizational knowledge transfer. MNCs rely on personal interactions to transfer knowledge across geographical, functional and cultural boundaries. IEs thus often perform boundary-spanning roles (Reiche 2011; Reiche et al. 2009). During their assignments, IEs increasingly link previously unconnected knowledge resources within their organization (Lakshman and Lakshman 2017; Reiche 2011; Reiche et al. 2009). These time and access advantages in regard to knowledge extend from IEs’ broad social networks (Boyle et al. 2016; Wang 2015); they are realized through discussions, specifically small talk, between IEs and host country nationals (Shimoda 2013). Hence, IEs ameliorate communications between subsidiaries and headquarters (e.g., Horak and Yang 2016; Ismail 2015; Ismail et al. 2016, 2019) and contribute to the creation of both intellectual capital (Reiche et al. 2009) and interunit social capital (Moeller et al. 2016; Reiche et al. 2009). This transferred knowledge is either tacit or explicit (Jannesari et al. 2016). The transfer of both types of knowledge between organizational units also builds on trust-based collaborations involving IEs and locals (Miesing et al. 2007), while the transfer of tacit knowledge ensures competitive advantages (Mors 2010; Sapouna et al. 2016; Zaragoza-Sáez and Claver-Cortés 2011). The more tacit, complex or specific the knowledge that is transferred, the less it is shared by IEs (Wu et al. 2021). Furthermore, IEs’ social capital allows the coordination and integration of operations and hence may replace other management means of coordination and control (Egbe et al. 2018; Harzing et al. 2016; Mäkelä et al. 2012b; Pudelko and Tenzer 2013). IEs’ social capital thus clearly benefits organizational knowledge transfer through IEs’ boundary-spanning roles. Specifically, small talk between IEs and host country nationals cultivates trust and information flow. Accordingly, international assignment jobs should be designed to allow IEs to interact frequently with both their host and home country colleagues.

4.4 Translating conditions

A few studies in our literature sample have shown that IEs’ social capital cannot guarantee enhanced individual and organizational outcomes. Scholars have identified several conditions that may foster or diminish the actual leverage of IEs’ social capital in terms of beneficial individual and organizational outcomes. We summarize these conditions below as IEs’ perceptions, support provider characteristics and host/home country factors.

4.4.1 IEs’ perceptions

Prior research has suggested that the benefits that IEs may generate from their social capital for themselves and their organizations are dependent on their perception of their job and their relationship with their organization. For instance, the translation of IEs’ social capital is dependent on the extent to which their employing organization meets their expectations. A psychological construct defines these individual perceptions and mutual obligations between IEs and their employers (Rousseau 1989). Psychological contract breaches, e.g., through unmet career advancement expectations, incline IEs toward turnover, leaving the potential leverage of their social capital upon their return untapped (Aldossari and Robertson 2016; Lee and Kartika 2014). In the same vein, IEs’ perceived organizational support influences the relationship between their social capital and various individual and organizational outcomes (Lee and Kartika 2014). Additionally, IEs who perceive their job knowledge and international experience to be relevant to their job make better use of their social capital (Mooney et al. 2016; Reiche 2011) affirming other research showing that IEs must be vested in the opportunity to share knowledge to actually engage in knowledge transfer (Wu et al. 2021). Therefore, IEs’ perceptions play a critical role in the translation of their social capital into positive outcomes. While the above sections have indicated rather hard factors, e.g., job designs that promote building social capital, this section thus points to a softer factor, highlighting the importance of IEs’ perceptions in the translation of their social capital into individual and organizational outcomes.

4.4.2 Support providers’ characteristics

Some of the articles in our sample indicate that the actual leverage of IEs’ social capital in outcomes is moderated by characteristic factors of IEs’ support providers. In their systematic literature review regarding IEs’ support and career success, van der Laken and colleagues conclude that geographical and hierarchical distances between support providers and IEs result in disparate career outcomes (van der Laken et al. 2016). For instance, IEs show lower adjustment levels when they receive support from geographically distant colleagues, and mentoring roles promote IEs’ host country adjustment if their mentors are host country nationals. van der Laken et al. (2016) further report that in terms of supervisory support, subsidiary supervisor support is more beneficial for IE adjustment and retention and that home country supervisors positively moderate the relationship between IEs’ performance and career success. However, IEs in supervisory positions may encounter more difficulties in accessing support from host country nationals than IEs in peer or subordinate positions (Varma et al. 2011). In addition to these hierarchical and geographical factors, IEs’ support providers’ disposition plays a moderating role in IE social capital leveraging in terms of their motivation to help (van der Laken et al. 2016), their empathy toward IEs (Van Gorp et al. 2017b) and their host country expertise (Farh et al. 2010). Recent research has also pointed to the differing perceptions of host country nationals and IEs. While host country nationals perceive all self-initiated and assigned expatriates to be out-group members, self-initiated IEs perceive themselves as in-group members (Guo et al. 2021), which may have a different effect on the translation of their social capital into outcomes than that of assigned IEs. Depending on their support providers’ ability and willingness to help, IEs perceive the quality of provided support differently, with consequences for distinct individual outcomes (Boyle et al. 2016; Pinto and Araújo 2016). Hence, the mere existence of social support programs for IEs appears to be insufficient for the translation of IEs’ social capital into individual and organizational outcomes. The hierarchical, geographical and motivational dispositions of IEs’ support providers influence how IEs’ perceived social support is translated into positive outcomes.

4.4.3 Host/home country factors

Only three articles in our sample study the moderating effect of host- and home-country factors on the leveraging of IEs’ social capital in outcomes. While in some contexts national factors may have a positive effect on the leveraging of IE social capital, in other contexts, the effect of national factors may actually be negative. For instance, according to Bader and Schuster (2015), IEs’ social networks are more beneficial for their psychological well-being when they are in terrorism-endangered countries. However, national policies (e.g., Qatarization) can also impede IEs’ career advancement in their host country, even when they have acquired social capital there (Rodriguez and Scurry 2014). Similarly, benefiting from host country networks upon IEs’ return to their home country is difficult for those returning to xenophobic home countries (Wang 2015). Despite the small amount of research on the national factors affecting the leveraging of IE social capital in outcomes, the extant knowledge allows us to conclude that individuals and organizations should be aware of any national peculiarities in their respective host and home countries that may impede the benefits extending from their IEs’ social capital.

Our systematic literature review has thus allowed us to develop a holistic overview of the current understanding of social capital in international careers. Based on the above research, we now identify some important areas that merit further attention.

5 Future research agenda

The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of prior research on (a) how IEs’ social capital is formed and (b) how and under which conditions IEs’ social capital is translated into individual and organizational outcomes. One question that has guided us in formulating our research and engaging in this endeavor is when IEs’ social capital is mutually beneficial and when it is not. We have found that to answer this question, a variety of factors must be considered. In this research, we have integrated perspectives from across individual and organizational levels and provided insights into how these factors interact to form and leverage IEs’ social capital. This method can inform future studies that are more rigorous and organize this research into a united framework. Our holistic review allows us to identify knowledge gaps for investigation in future research and to outline research questions that if addressed, are likely to deepen and extend our understanding of the focal phenomenon. In this section, we explore six main areas that deserve further attention and offer promising avenues for future research. We provide a synthesized overview of these in Table 1. We then close this chapter with a call for more interdisciplinary research and a discussion of some implications for practitioners.

5.1 Antecedents forming IEs’ social capital

First, more research on the individual antecedents of IEs’ social capital is needed to better understand how IEs build social capital. In particular, the field would benefit from research on IEs’ personality traits. For instance, IEs’ self-monitoring likely promotes their social capital formation, as individuals high in self-monitoring better manage their existing contacts while acquiring new ones (Sasovova et al. 2010). This may explain why some IEs build large and diverse networks as opposed to close and dense networks (Selden and Goodie 2018). Additionally, future research, building on previous cross-sectional studies (e.g., Agha-Alikhani 2016; Harrison and Michailova 2012), could analyze in greater detail how different types of IE acquire distinct forms of social capital.

5.2 Cultural aspects of IEs’ social capital

Scant research has explored the role of culture in IEs’ social capital formation. Specifically, we address (1) the role of culture in IEs’ trust building and (2) of IEs’ cultural identity and language in creating shared cognitive grounds. First, more research is needed to understand the cultural and national antecedents of IEs’ social capital. The building of trust is incremental in the formation of new relationships, and the perception and building of trust as well as the norms of reciprocity that derive from trust are subject to cultures (Fukuyama 1995). An interesting scholarly endeavor would thus be to determine how IEs’ trust building behaviors change as they are immersed in the value system of their host country’s culture. Does their way of perceiving and evaluating trust in relationships change? How does the culture of their host country affect IEs’ relational social capital? Cross-cultural studies exploring the influence of culture on IEs’ social capital formation will help answer these questions. Second, we draw scholars’ attention to the need for a better investigation of the cognitive dimension of IEs’ social capital. Specifically, we focus on cultural identity and language. IEs’ cultural identities may cause changes in the cultural diversity of their networks (Mao and Shen 2015). Promising contributions are likely to emerge from investigations of how IEs’ immersion in a foreign culture affects their networks’ cultural diversity and whether this effect, in the long term, disappears within a new, emerging social network that primarily consists of foreign and/or multicultural contacts. Regarding the effects of language, no study in our literature sample addresses the effects of language on the formation of social capital. In the broadest sense, Wang and Kanungo (2004) show that the social networks of IEs with disparate origins in China vary in size, diversity and closeness. Future research may therefore explain how these differences in social networks come into existence from a language perspective and derive practical recommendations for how IEs can overcome the challenge of establishing shared cognitive grounds (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998) with host country nationals.

5.3 Behavioral lens on IEs’ social capital formation and leverage

To better understand how IEs’ social networks are created, we now emphasize IEs’ individual actions and behaviors. In particular, we suggest that future research should focus more on the distinct behaviors of IEs for building and leveraging social relationships. We address (1) IEs’ networking behavior in their formation of social capital and (2) IEs’ brokerage behavior in their leveraging of social capital. First, research explaining how IEs’ behavior contributes to the formation of their social capital is lacking. Although a few studies explore IEs’ use of online social networks and boundary-spanning roles, little is known regarding which IE actions in particular build social capital, leaving them in a rather inactive role. However, empirical evidence shows that individuals demonstrate various levels of activity when building social capital depending on their organizational embeddedness (Ng and Feldman 2010). The time is ripe for further development in this area, and we suggest that researchers investigate IEs’ networking behavior. Forret and Dougherty’s (2001, 2004) concept of networking behavior may provide a useful starting point. They distinguish among socializing, maintaining, engaging in professional activities, participating in social communities, and increasing internal visibility within one’s company. Research in this direction may provide practitioners with valuable information on which networking behavior leads to the formation of IEs’ social capital and when IEs display different levels of agency. Second, we call scholars’ attention to the behavioral strategies IEs engage to make use of their social capital. In particular, IEs in a bridging position have the power to either connect two otherwise disconnected alters (‘tertius iungens’) or to keep them separate (‘tertius gaudens’). According to the integrative review of Kwon et al. (2020), tertius iungens facilitates collaboration between while tertius gaudens gains control of the information flows between two alters. Future research considering the concept of brokerage behavior is therefore likely to provide an important understanding of the “why” and “how” of social capital outcomes rather than their mere “what”.

5.4 Methodological endeavors for exploring IEs’ social capital

We call for methodologically more ambitious research designs that account for (1) the dynamic nature of IEs’ social capital and (2) the multiple levels on which social capital can be accumulated and leveraged. First, scholarly efforts to demonstrate how networks change over time would help us better understand which temporal benefits arise from IEs’ structural social capital for individuals and organizations. For example, IEs may temporarily benefit from multiple group memberships, as they are socially embedded in both their host country and home country organizations (Burt et al. 2013; Kilduff and Brass 2010); however, as geographically distant relationships vanish over time, this structural social capital may ultimately disappear (Bruning et al. 2012; Kimber 2019; Mäkelä and Suutari 2009). Longitudinal research would therefore better explain IEs’ network dynamics and help organizations retain important advantages of IEs’ social networks. Given that many IEs accept several foreign assignments throughout their careers and that international experience is no longer limited to a once-in-a-lifetime event (Cao et al. 2014), longitudinal research could also explain the effects of social capital on IEs’ intention to continue their international careers. In-depth research into how IEs’ social capital influences their sense-making of their international careers and future career prospects will assist organizations in developing adequate global career development programs and thus contribute to the retention of global talent. Second, to date, research on IEs’ social capital has been limited to the individual level. Scholars must urgently move away from these individual-level, ego-centered approaches and undertake group- and multilevel perspectives to better understand the organizational social networks in which IEs operate. For instance, do IEs act in a dense network where many alters are interconnected, or is their organizational network rather sparse, with many structural holes? Social network analyses that are not egocentric but examine whole organizational networks would allow a better understanding of how IEs’ social capital unfolds in the organizational network context (Burt et al. 2000). Furthermore, mixed-method approaches (e.g., combining social network analysis with interview techniques) taking IEs’ network alters into account should offer insights into how coworkers benefit from IEs’ social capital.

5.5 The dark side of IEs’ social capital