Abstract

Motivated by geological carbon storage and hydrocarbon recovery, the effect of buoyancy and viscous forces on the displacement of one fluid by a second immiscible fluid, along parallel and dipping layers of contrasting permeability, is characterized using five independent dimensionless numbers and a dimensionless storage or recovery efficiency. Application of simple dimensionless models shows that increased longitudinal buoyancy effects increase storage efficiency by reducing the distance between the leading edges of the injected phase in each layer and decreasing the residual displaced phase saturation behind the leading edge of the displacing phase. Increased transverse buoyancy crossflow increases storage efficiency if it competes with permeability layering effects, but reduces storage efficiency otherwise. When both longitudinal and transverse buoyancy effects are varied simultaneously, a purely geometrical dip angle group defines whether changes in storage efficiency are dominated by changes in the longitudinal or transverse buoyancy effects. In the limit of buoyancy-segregated flow, we report an equivalent, unidimensional flow model which allows rapid prediction of storage efficiency. The model presented accounts for both dip and layering, thereby generalizing earlier work which accounted for each of these but not both together. We suggest that the predicted storage efficiency can be used to compare and rank geostatistical realizations, and complements earlier heterogeneity measures which are applicable in the viscous limit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Reservoir properties such as permeability and porosity vary over many length scales, from the kilometre scale down to the micron scale, in response to complex physical and chemical processes, including structural deformation, deposition and diagenesis (Koltermann and Gorelick 1996). Both the geometrical distribution of reservoir properties and the length scales at which these vary have a profound influence on multiphase flow in the subsurface (Weber 1986). The sedimentary rocks that commonly act as subsurface reservoirs typically exhibit layering (i.e. alternations of continuous, parallel strata with contrasting lithological and petrophysical properties) at length scales ranging from mm-scale laminations to km-scale stratigraphy (e.g. Campbell 1967; Koltermann and Gorelick 1996; De Marsily et al. 1998; Jackson et al. 2003; Deveugle et al. 2011, 2014; Legler et al. 2013). At all scales, the layers may have a dip imposed on them either by depositional features (e.g. Graham et al. 2015; Massart et al. 2016) or by structural deformation (e.g. Koltermann and Gorelick 1996). Understanding multiphase flow in dipping, layered reservoirs is important in industrial and environmental processes such as geologic \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage, contaminant remediation and hydrocarbon recovery.

Here, we determine the effect of buoyancy and viscous forces on the displacement of one fluid by a second immiscible fluid, along parallel and dipping layers of contrasting permeability. Such displacements are typically influenced by a combination of viscous, capillary and gravitational forces (e.g. Ringrose et al. 1993; Kjonsvik et al. 1994; Jones et al. 1995; King and Mansfield 1999; White and Barton 1999). This paper is the third of a series that investigates flow in layered porous media and focuses on flow driven by buoyancy and viscous forces. The impact of viscous and capillary forces on flow along and across layers has been previously considered in the first two papers of this series (Debbabi et al. 2017a, b). We consider the downwards injection of a fluid which is less dense than the fluid in place, so results are directly applicable to geologic \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage and gas flooding of hydrocarbon reservoirs. However, the symmetry of the problem allows application of the results to the upwards injection of a fluid which is more dense than the fluid in place by inverting the layer order, so results are also applicable to waterflooding of hydrocarbon reservoirs. The aim of the work is not to predict exactly the behaviour of a given system, but rather to predict how the storage or recovery efficiency, a key measure of reservoir performance, is determined by the buoyancy–viscous force balance using a small number of key dimensionless parameters. As discussed previously by Debbabi et al. (2017a, b), such results provide a framework to support mechanistic interpretations of complex field or experimental data, and numerical model predictions. Quantifying the system behaviour using storage efficiency (fraction of the moveable pore volume occupied by the injected phase) makes results directly applicable to geologic \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage (e.g. Cavanagh and Ringrose 2011), but also to hydrocarbon recovery using the numerically equivalent recovery efficiency (fraction of the moveable pore volume initially in place recovered) (e.g. Christie and Blunt 2001).

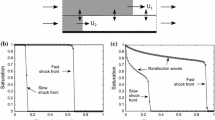

The viscous- and buoyancy-driven displacements of one fluid phase by another have been previously investigated both experimentally and numerically using immiscible fluids and miscible analogs. When viscous forces dominate over buoyancy forces, the injected phase tends to progress more rapidly through layers of higher permeability (Debbabi et al. 2017a) (Fig. 1c). Crossflow due to transverse fluid mobility contrasts, termed viscous crossflow, typically occurs when layers are not separated by impermeable flow barriers. Crossflow directions have been shown to be controlled by the mobility ratio estimated across the leading edge of the injected phase in each layer. When buoyancy forces dominate over viscous forces, the injected phase forms a ‘tongue’ which under-rides the fluid in place if the injected phase is more dense than the fluid in place, or over-rides the fluid in place otherwise (Dietz 1953; Craig et al. 1957; Lake 1989; Ingsoy and Skjaeveland 1990; Gunn and Woods 2011; Pegler et al. 2014; Zheng et al. 2015) (Fig. 1a). However, buoyancy forces in dipping systems may also stabilize the interface separating the injected and displaced phases (Fig. 1b). The stabilization resulting from these “dip-related buoyancy effects” can prevent early breakthrough of the injected phase, provided the flow rate is sufficiently reduced or the dip angle sufficiently large (Dietz 1953; Fayers and Muggeridge 1990; Ekrann 1992). When both viscous and buoyancy forces are important, buoyancy-driven counter-current flow between layers, more commonly termed “buoyancy crossflow”, repositions the denser phase below the lighter phase wherever viscous-driven flow leads to buoyancy-unstable fluid distributions (Richardson et al. 1952; Gaucher and Lindley 1960; Huppert et al. 2013). Earlier work has shown that optimum storage efficiencies may be obtained when viscous and buoyancy forces compete, provided permeability varies monotonically in the transverse direction (Peters et al. 1998; Permadi et al. 2004). However, the impact of buoyancy crossflow on fluid distribution and storage efficiencies becomes more complex when transverse permeability variations are non-monotonic (Ahmed et al. 1988; Stewart 2014). Earlier work has also shown that buoyancy forces reduce the remaining displaced phase saturation in regions contacted by the injected phase relative to the viscous-limit case (Lake 1989; El-Khatib 2012).

Previous studies highlighted the complex, competing relationships between buoyancy crossflow, dip-related buoyancy effects and storage efficiency (Fig. 1). However, most previous studies of flow along dipping layers either assume significant buoyancy crossflow, or neglect dip-related buoyancy effects. These earlier results, therefore, do not quantify the relative importance of buoyancy crossflow and dip-related buoyancy flow, so it is difficult to predict which effect controls the storage efficiency, or identify the contribution of dip-related buoyancy effects to fluid distribution and storage efficiency in layered systems.

Here we characterize immiscible, two-phase flow through dipping, layered porous media using seven dimensionless parameters, five of which are independent, obtained from an inspectional analysis of the flow equations. The outline of the paper is as follows. After first presenting the mathematical model (Sect. 2), we then present in Sect. 3 the seven dimensionless numbers that are used to characterize flow. We examine in Sects. 4.1 and 4.2 the impact of longitudinal and transverse buoyancy effects on fluid distribution. We quantify in Sect. 4.3 storage efficiency as a function of the dimensionless parameters, first when flow transitions from the viscous limit to the buoyancy limit via numerical simulations (Sect. 4.3.1), and then present a 1D fractional flow model that allows rapid estimation of storage efficiency in dipping, layered systems when flow is buoyancy segregated (Sect. 4.3.2). The implications of this analysis are discussed in Sect. 5, and finally, in Sect. 6, we gather the main conclusions.

Buoyancy-to-viscous flow diagram expressed in terms of longitudinal and transverse buoyancy numbers defined in Table 1. Schematics represent typical distribution of regions that are contacted by the less dense, injected phase (coloured in grey) along layers of high (H) and low (L) permeabilities in the different flow domains. We demonstrate in this paper that longitudinal buoyancy effects reduce the separation of the leading edges of the injected phase in each layer caused by permeability contrasts (d). Indicative boundaries of the different flow domains are suggested as dashed lines in the flow diagram. Changing other dimensionless parameters such as the end-point mobility ratio or the permeability ratio affects the specific location of these domain boundaries but their general shape remains unchanged

2 Mathematical Model

Following Debbabi et al. (2017a, b), we investigate two-phase, immiscible and isothermal flow through a two-dimensional (2D), two-layered porous medium in which the layers have contrasting petrophysical properties, and additionally account here for dip, which has an influence on flow when buoyancy forces are not negligible (Fig. 2).

Assuming the fluids and pore space are incompressible, that the pore space is completely filled with both fluids, and neglecting capillary forces, flow is described by

and the multiphase Darcy’s law

where

is the normalized injected phase saturation, which varies between 0 and 1, \(S_i\) is the injected phase saturation, \(S_{i,r}\) and \(S_{d,r}\) are the injected and displaced phase residual saturations, \(\Delta S=1-S_{i,r}-S_{d,r}\) is the moveable saturation, \(\phi \) is the porosity, \(\mathbf {q}_\mathbf{i}\) and \(\mathbf {q}_\mathbf{d}\) are the injected and displaced phase volumetric fluxes per unit area, \(\mathbf {q}_\mathbf{T}\) is the total volumetric fluid flux per unit area, \(k_{r,i}(s\)) and \(k_{r,d}\left( s\right) \) are the relative permeabilities of the injected and displaced phases, \({\mu }_i\) and \({\mu }_d\) are the viscosities of the injected and displaced phase, \(\overline{\overline{k}}\) the diagonal absolute permeability tensor, \({\rho }_i\) and \({\rho }_d\) are the densities of the injected and displaced phase, and P the fluid pressure. The injected and displaced phase fluid mobilities are defined as

and

respectively, and the total fluid mobility \({\lambda }_T\) as

The relative permeability curves are represented as functions of the normalised saturation s by

where \(k^e_{r,i}\) and \(k^e_{r,d}\) are the end-point relative permeabilities, and \(n_i\) and \(n_d\) the Corey exponents of the injected and displaced phases, respectively. Each layer is internally homogeneous, with identical thickness H / 2, length L, porosity \(\phi \) and moveable saturation \(\Delta S\), but the layers may differ in longitudinal absolute permeability \(k_x\), and end-point relative permeabilities \(k^e_{r,i}\) and \(k^e_{r,d}\). However, the Corey exponents \(n_i\) and \(n_d\) are chosen to be the same in both layers, and the end-point relative permeabilities \(k^e_{r,i}\) and \(k^e_{r,d}\) are constrained to obtain identical fractional flow curves in both layers (see Appendix 1 in Debbabi et al. 2017a). The impact of contrasts in fractional flow curves and moveable pore volumes between layers was examined in the first two papers in this series (Debbabi et al. 2017a, b). The layers have identical transverse permeability \(k_z\) such that \(k^1_z=\ k^2_z\le \mathrm {min}\mathrm {}(k^1_x,k^2_x)\), where \(k^1_z\) and \(k^2_z\) are the transverse permeabilities of layers 1 and 2, respectively. Layers that have different longitudinal permeabilities may also differ in transverse permeability but contrasts in transverse permeability are not investigated here. Previous studies have shown that viscous and capillary crossflow are not significantly modified by such contrasts, as crossflow is limited by the lowest transverse permeability (Debbabi et al. 2017a, b).

Initially (\(t=0\)), the potential \({\varvec{\Phi }}=P+\rho \,g\,\cos {(\alpha )}z\) is uniform and the normalized saturation is zero throughout the domain (\(s=0\)). At the inlet face, the boundary conditions are uniform, but time-varying potential (\({\varvec{\Phi }}={{\varvec{\Phi }}}_{in}\left( t\right) \)) and a constant total volumetric flux \(Q_{in}\) of the injected phase, distributed to yield a corresponding average volumetric influx per unit area along the inlet face \({\overline{q}}_{in}\) such that the inlet potential remains uniform. The other boundary conditions are a fixed potential \({{\varvec{\Phi }}}_0\) on the outlet (opposing) face, and no flow across the other faces. This choice of boundary conditions extends the approach used in Debbabi et al. (2017a) to additionally account for gravity and is likewise consistent with borehole boundary conditions used in groundwater and oil reservoir models (Aziz and Settari 1979; Wu 2000).

Following Debbabi et al. (2017a, b), solutions of the multiphase flow Eqs. (1)–(4) were obtained using a commercial code that implements a finite-volume-finite-difference approach to discretize the governing equations (Eclipse 100). Flow was simulated using two-dimensional Cartesian grids with resolutions ranging from \(200 \times 200\) up to \(800 \times 800\) cells to demonstrate that the solutions were converged. Time stepping was fully implicit.

3 Scaling Analysis

The flow eqs. (1)–(4) are scaled following the inspectional analysis reported by Debbabi et al. (2017a), but additionally account for buoyancy forces. We obtain seven dimensionless numbers, five of which are independent, to describe immiscible, two-phase flow along dipping layered porous media (see Appendix 1). The dimensionless numbers are summarised in Table 1.

The buoyancy number \(N_{bv}\) can be interpreted as the ratio of the characteristic longitudinal pressure drop due to fluid density differences to that due to viscous forces. Our definition differs from the buoyancy number reported by Shook et al. (1992) as we account here for contrasts in the relative permeability end-points between layers. We demonstrate in the no-crossflow limit (see Appendix 2) that the fluid in place may flow out (“backflow”) through the lower parts of the inlet face when \(N_{bv}>2\). We restrict this work to \(N_{bv}\le 2\) to focus on general results that are insensitive to the details of inflow and outflow at the inlet face. This does not limit application of the results to systems of interest (see Figs. 3, 4).

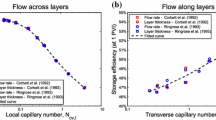

The effective aspect ratio \(R_L\) quantifies the relative flow capacities of the medium in the longitudinal and transverse directions. The definition used in this paper again differs from previously used numbers (e.g. Zhou et al. 1997) as we account for contrasts in the relative permeability end-points between layers. The effective aspect ratio \(R_L\) typically varies over the range \(0.01-100\) in layered sedimentary systems (L / H is typically large, of order \(10-100\), while \(k_z/k_x\) is typically small, of order \(10^{-6}-1\)). The product of \(N_{bv}\) and \(R^2_L\) yields the transverse buoyancy number \(N_{bv,T}\), which can be interpreted as the characteristic time ratio for fluid to flow in the longitudinal direction due to viscous forces to that in the transverse direction due to buoyancy forces. The transverse buoyancy number \(N_{bv,T}\) is similar to the dimensionless buoyancy-to-viscous ratio reported by Zhou et al. (1997), except that here we again account for contrasts in the relative permeability end-points between layers. We show later in this work that the onset of buoyancy crossflow occurs when \(N_{bv,T}>0.1\). Data taken from bead-pack experiments (Ingsoy and Skjaeveland 1990), field-scale waterflooding (C&C Reservoirs 2016), and \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injections into geologic formations (Guo et al. 2016) confirm that possible values of the effective aspect ratio and the transverse buoyancy number span at least four and seven orders of magnitude, respectively (Fig. 3).

Possible combinations of the effective aspect ratio \(R_L\) and the transverse buoyancy number \(N_{bv,T}\) calculated using data from bead-pack experiments (Ingsoy and Skjaeveland 1990), field-scale waterflood operations (C&C Reservoirs 2016) and \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injections into geologic formations (Guo et al. 2016). The dashed line represents the boundary at which \(N_{bv}=2\)

The dip angle group \(N_{\alpha }\), which is a purely geometrical group, is identical to the number introduced by Shook et al. 1992, and inversely correlates with the impact of buoyancy over- or under-ride on fluid distribution. The product of \(N_{bv}\) and \(N_{\alpha }\) yields the longitudinal buoyancy number \(N_{bv,L}\), which can be interpreted as the characteristic time ratio for fluid to flow in the longitudinal direction due to viscous forces to that due to buoyancy forces. The longitudinal buoyancy number \(N_{bv,L}\) is similar to the buoyancy number used in the fractional flow theory for immiscible displacements (Lake 1989); however, here we again account for contrasts in the relative permeability end-points between layers. We show later in this work that longitudinal buoyancy effects become significant when \(N_{bv,L}>0.1\). Data taken from field-scale waterflood operations confirm that possible values of the longitudinal buoyancy number and dip angle group span at least seven and three orders of magnitude, respectively (Fig. 4).

Possible combinations of the dip angle group \(N_\alpha \) and the longitudinal buoyancy number \(N_{bv,L}\) calculated using data from field-scale waterflood operations (C&C Reservoirs 2016). The dashed line represents the boundary at which \(N_{bv}=2\)

The longitudinal permeability ratio \({\sigma }_x\) quantifies permeability heterogeneity and is identical to the expression suggested by Debbabi et al. (2017a) except that here we account for layer ordering: if \({\sigma }_x>1\) then the upper layer 1 has the higher permeability, whereas if \({\sigma }_x<1\) then the lower layer 2 has higher permeability. A suite of core-plug measurements taken along a single well from a North Sea field (Tjølsen et al. 1991) shows that plausible permeability ratios span three orders of magnitude (see Fig. 3 in Debbabi et al. (2017a)). Here, for the sake of generality, we do not restrict the combinations of permeability ratio investigated, varying the permeability ratio over the range \(0.01\le {\sigma }_x\le 100\).

The end-point mobility ratio \(M_e\) describes the ratio of the injected and displaced phase end-point mobilities. The end-point mobility ratio may range between 0.0001 and 10, 000, given that the ratio of end-point relative permeabilities ranges between 1 and 10, and the ratio of the fluid viscosities between 1 and 1, 000. When the two phases are segregated by buoyancy forces, the relative permeability curves only influence the displacement via their end-points, so the end-point mobility ratio is sufficient to parameterize flow. However, in the viscous limit, the two phases may flow simultaneously so the shape of the relative permeability curves is important. In particular, the shape of the curves influences the viscous crossflow behaviour. We showed in a companion paper that the relative permeability curves can be scaled using the shock-front mobility ratio \(M_f\), which describes the ratio of the total mobilities calculated at the upper and lower saturation values that bound the discontinuity that defines the shock obtained in the viscous limit (Debbabi et al. 2017a). We demonstrated that there is a consistent change in viscous crossflow behaviour at \(M_f=1\). In this work, we prefer to use the end-point mobility ratio to focus our analysis on buoyancy effects, and choose \(M_e=0.5.\) Using Corey exponents \(n_i=n_d=2\), this value yields favourable viscous crossflow, which occurs from the high to the low permeability layer (\(M_f=0.4<1\)). However, numerical experiments not reported here show that varying the end-point mobility ratio to yield unfavourable viscous crossflow (\(M_f>1\)) has no influence on the conclusions of this paper.

We quantify the impact of the dimensionless numbers on flow characterized in terms of a dimensionless storage efficiency (see also Debbabi et al. 2017a, b), defined as

The storage efficiency measures how effectively the injected phase is retained within the model domain, and is relevant when characterizing the geologic storage of carbon in subsurface reservoirs and the location of NAPLs in contaminated aquifers. The storage efficiency is also numerically equivalent to the recovery efficiency, which is a measure of how effectively the displaced phase is removed from the model and is relevant to hydrocarbon production. Quantifying the effect of the dimensionless numbers in terms of the storage/recovery efficiency (henceforth termed the storage efficiency) therefore yields results of broad interest. To further analyse the controls on storage efficiency, we also decompose storage efficiency following Lake (1989) into the product of sweep efficiency, defined as

which measures the fraction of the moveable pore volume contacted by the injected phase, and displacement efficiency, defined as

which quantifies the fraction of the contacted moveable pore volume which has been displaced by the injected phase. We report these various efficiencies measured at breakthrough time (BT), i.e. when the injected phase flux through the outlet face exceeds 1% of the total flux. This ensures the results remain broadly applicable regardless of the type of boundary represented by the outlet face of the model (e.g. borehole, open boundary, symmetry element of a larger domain). After breakthrough, the nature of the outlet boundary can affect the fluid potential at the boundary and so the results become less general.

4 Results

4.1 Impact of Longitudinal Buoyancy Effects on Saturation Distribution

To understand the underlying controls on flow, we first examine the impact of longitudinal buoyancy effects on fluid distribution in the absence of any transverse flow within or across layers (\(R_L=N_{bv,T}=0\)). This scenario is unlikely to occur in real reservoirs, but could be approached, for example, in steeply dipping layers (so there is little transverse flow within layers) separated by extensive barriers to flow such as mudstones or cements (see, for example, Choi et al. 2011). Snapshots of the saturation distribution in two layers of contrasting permeabilities (\({\sigma }_x=10)\) for two different values of the longitudinal buoyancy number \(N_{bv,L}\) confirm that increased longitudinal buoyancy effects reduce the remaining displaced phase saturation in regions contacted by the injected phase (Fig. 5b), in agreement with 1D fractional flow theory (Lake 1989). The results also show that increased longitudinal buoyancy effects reduce the distance between the leading edges of the injected phase in each layer (Fig. 5a, b). This is surprising without crossflow, and we demonstrate in Appendix 2 that it is a consequence of the uniform potential boundary conditions. At early times, the less dense injected phase moves faster in high permeability layers, but buoyancy effects become less significant as the average fluid density in the layer decreases. This reduces the velocity of the injected phase relative to the velocity achieved in low permeability layers where the average fluid density is higher. The leading edges of the injected phase are, therefore, closer with than they are in the equivalent case but without fluid density contrasts. Numerical experiments, not reported here, further demonstrate that the layer ordering has little influence on fluid distribution. This symmetry is expected when buoyancy effects in the transverse direction are negligible.

a Saturation distribution in layers with no transverse flow or crossflow but with contrasting permeability after 0.5 moveable pore volumes (MPV) injected for two different values of the longitudinal buoyancy number \(N_{bv,L}\). b Saturation as a function of distance along the centre of each layer shown in (a)

4.2 Impact of Buoyancy Crossflow on Saturation Distribution

We now examine the impact of buoyancy crossflow on saturation distribution without longitudinal buoyancy effects (Fig. 6). Longitudinal buoyancy effects (\(N_{bv,L}\)) are negligible when, for example, the dip is small (\(\alpha \sim 0{}^\circ \); see definition of \(N_{bv,L}\) in Table 1). We consider layers of contrasting permeability and vary the amount of buoyancy crossflow (\(N_{bv,T}\)) and layer ordering (\(\sigma _x=10\) and 0.1). The effective aspect ratio is maintained fixed and greater than zero (\(R_L=10\)), to allow viscous and buoyancy crossflow. When the high permeability layer is on the top (\(\sigma _x=10\); Fig. 6a), the displacement is in a buoyancy-stable configuration. Most of the less dense, injected fluid remains above the more dense fluid in place, except for the remaining displaced phase saturation within the region contacted by the injected phase. Increased buoyancy effects both reduce the remaining displaced phase saturation, despite the absence of longitudinal buoyancy effects, and lead to the development of a buoyancy tongue that preferentially sweeps the upper part of the system. When the high permeability layer is on the bottom (\(\sigma _x=0.1\); Fig. 6b), the displacement is in a buoyancy-unstable configuration. The less dense, injected phase is preferentially injected through the high permeability layer, below the denser fluid initially in place. Buoyancy then causes counter-current crossflow to reposition the lower density phase on top and vice-versa. These results (Fig. 6a, b) confirm earlier work (e.g. Ekrann 1992; Peters et al. 1998; Huppert et al. 2013): layer ordering exerts a major control on the impact of buoyancy crossflow on fluid distribution, and heterogeneity may also delay buoyancy segregation when viscous and buoyancy forces compete to control fluid distribution. We note that the numerical results obtained when buoyancy and heterogeneity effects compete (i.e. with \(N_{bv,T}=10\) in Fig. 6a) do not show any form of Rayleigh–Taylor instability, although this has been observed experimentally with miscible fluids by Huppert et al. (2013). We explain this finding by the absence of intra-layer permeability heterogeneity to trigger the instability.

Snapshots of the saturation distribution in two layers with contrasting permeability after 0.4 MPV injected for different values of the transverse buoyancy number \(N_{bv,T}\) and different layer orderings. Dashed lines denote the boundaries between the high and low permeability layers. In Sect. 4.3.2, in the limit of buoyancy-segregated flow (\(N_{bv,T}\ge 100\)), we quantify the two-phase flow problem in terms of the fractional thickness \(\hat{h}\) occupied by the injected phase

4.3 Storage/Recovery Efficiency

We continue our analysis by exploring the storage/recovery efficiency as a function of the dimensionless parameters when flow transitions from the limit of viscous-dominated to buoyancy-dominated flow. Correlations that are applicable in the viscous limit are reported in a companion paper (Debbabi et al. 2017a). The correlations reported here provide a useful basis for the interpretation of more complex numerical reservoir models used to quantitatively predict storage or recovery efficiency. We also demonstrate how to rapidly predict storage efficiency in the limit of buoyancy-segregated flow using a 1D fractional flow model analog to the Buckley–Leverett model.

4.3.1 Transition From the Viscous Limit to the Buoyancy Limit

We begin by examining the relationships between the dimensionless parameters and storage efficiency when flow transitions from the viscous limit to the buoyancy limit.

Longitudinal buoyancy effects We first determine the relationship between storage efficiency and longitudinal buoyancy effects without transverse flow within or crossflow across layers (\(R_L=N_{bv,T}=0\); Fig. 7). We consider a moderate permeability contrast with the high permeability layer on top (\({\sigma }_x=10\)); additional numerical experiments, not reported here, confirmed the layer ordering has little influence on the predicted trends. We vary \(N_{bv}\) between \({10}^{-4}\) and 1, and vary \(N_{\alpha }\) between 0.1 and 100. Storage efficiency is an increasing function of the longitudinal buoyancy number \(N_{bv,L}\) only (Fig. 7). These results show that longitudinal buoyancy effects only become significant when \(N_{bv,L}>0.1\). Figure 8 shows that the increase in storage efficiency can be attributed to increases in both sweep and displacement efficiency with \(N_{bv,L}\). This is in agreement with results reported in Fig. 5: increasing \(N_{bv,L}\) reduces the distance between the leading edges of the injected phase in each layer and reduces the remaining displaced phase saturation in regions contacted by the injected phase. The correlation reported generally applies when \(N_{bv,T}\) is varied along with \(N_{bv,L}\), as long as \(N_{bv,T}<0.1\), so buoyancy crossflow remains insignificant.

Buoyancy crossflow effects We now examine the relationship between storage efficiency and buoyancy crossflow in the absence of longitudinal buoyancy effects (\(N_{bv,L}=N_{\alpha }=0\)). We consider moderate permeability contrasts with the high permeability layer on top (\({\sigma }_x=10\)) and on the bottom (\({\sigma }_x=0.1\)). We vary \(N_{bv}\) between \({10}^{-4}\) and 1, and \(R_L\) between 10 and 100. We find that storage efficiency is a function of the transverse buoyancy number \(N_{bv,T}=N_{bv}R^2_L\) only, and increases when the upper layer is less permeable, or mildly decreases when the upper layer is more permeable (Fig. 9). Analysis of the sweep and displacement efficiencies reported in Fig. 10 explains the trends as follows. When the upper layer is less permeable than the lower layer, buoyancy crossflow increases injected phase crossflow from the high to the low permeability layer (see Fig. 6b). This increases sweep efficiency (Fig. 10; \(\sigma _x=0.1\)). Additionally, buoyancy crossflow, which tends to segregate the two fluids, also reduces the remaining displaced phase saturation in regions contacted by the injected phase. This increases displacement efficiency. Conversely, when the upper layer is more permeable, buoyancy crossflow further increases injected phase crossflow from the low to the high permeability layer (see Fig. 6a). This reduces sweep efficiency (Fig. 10; \(\sigma _x=10\)). However, buoyancy crossflow also increases displacement efficiency, again because buoyancy segregation reduces the remaining displaced phase saturation in regions contacted by the injected phase. The results also confirm that buoyancy crossflow becomes significant when \(N_{bv,T}>0.1\). The correlation reported generally applies when \(N_{bv,L}\) is varied along with \(N_{bv,T}\), as long as \(N_{bv,L}<0.1\), so longitudinal buoyancy effects remain insignificant.

Longitudinal buoyancy effects and buoyancy crossflow We now examine the relationship between storage efficiency and buoyancy effects when both longitudinal and transverse buoyancy effects may be significant (\(N_{bv,L},\ N_{bv,T}>0.1\)). We consider moderate permeability contrasts, with the high permeability layer on top (\({\sigma }_x=10\)) and on the bottom (\({\sigma }_x=0.1\)). We maintain \(R_L=10\) so buoyancy crossflow may occur as we increase \(N_{bv}\). We vary \(N_{bv}\) between \({10}^{-4}\) and 1, and \(N_{\alpha }\) between 0.1 and 10 to vary the relative importance of buoyancy crossflow and longitudinal buoyancy effects. When the upper layer is less permeable (Fig. 11a), storage efficiency increases with \(N_{bv}\) regardless of \(N_{\alpha }\) because increased longitudinal and transverse buoyancy effects both increase storage efficiency. When the upper layer is more permeable (Fig. 11b), storage efficiency either decreases with \(N_{bv}\) when \(N_{\alpha }\) is small (\(\le 1\) here), which is explained by the domination of unfavourable buoyancy crossflow, or increases with \(N_{bv}\) otherwise, due to the domination of favourable longitudinal buoyancy effects. Similar results were previously obtained for homogeneous systems (Shook et al. 1992). We conclude in general that longitudinal buoyancy effects dominate over buoyancy crossflow effects when \(N_{\alpha }\) is sufficiently large, but buoyancy crossflow dominates otherwise.

4.3.2 Limit of Buoyancy-Segregated Flow

In the limit of large transverse buoyancy numbers (\(N_{bv,T}\gg 1\)), buoyancy segregates the two phases so they flow through distinct regions, separated by a sharp interface (see examples in Fig. 6a, b with \(N_{bv,T}=100\)). In this limit, the two-phase flow problem reduces to the unidimensional problem of tracking the fractional thickness \(\hat{h}(\hat{x},\hat{t})\) occupied by the injected phase. We demonstrate in Appendix 3 that, in the limit of buoyancy-segregated flow, the fractional thickness \(\hat{h}\) satisfies the fractional flow equation

where \(f_b\) denotes the “buoyancy-limit fractional flow”, which is the ratio of the injected phase to the total fluid flux passing through a given transverse cross section of the system (see also Dietz 1953; Dake 1983; Lake 1989; Yortsos 1995; Gunn and Woods 2011). This fractional flow is given as a function of the fractional thickness and its gradient by

This expression generalises results reported by Yortsos (1995) without dip but layering, and the expression reported by Gunn and Woods (2011) with dip but no layering. Assuming \(N_{bv}\ll 1\), the fractional flow can be expressed as a function of the fractional thickness only (see examples given in Fig. 12a). This allows application of fractional flow theory, in particular to compute graphically, from a given fractional flow curve, the average fractional thickness behind the leading edge of the injected phase. The latter is numerically equivalent to the breakthrough storage efficiency in the limit of buoyancy-segregated flow. We next demonstrate how to estimate this breakthrough storage efficiency using two examples.

Figure 12a shows the fractional flow curves obtained for two dipping, two-layered systems (\(N_{bv}=0.03\); \(N_{bv,L}=3\); \(R_L=100\)) with different layer ordering (\({\sigma }_x=0.01\) and 100). Results from fractional flow theory show that the average fractional thickness \(\overline{h}\) behind the leading edge of the injected phase can directly be read from the fractional flow curve as the X-coordinate of the intersection (represented as dark points on Fig. 10a) between the horizontal line of equation \(f_b=1\) and Welge’s tangent to the fractional flow curves passing through the origin of the graph (represented as the dark plain lines in Fig. 10a) (Welge 1952). For the two examples reported in Fig. 12a, we read breakthrough storage efficiency/average fractional thickness values of 0.525 and 1 with \({\sigma }_x=100\) and 0.01, respectively. These values differ by less than 1% from values of breakthrough storage efficiency obtained numerically. Qualitative comparisons of snapshots of saturation distributions with the estimated average tongue thickness also confirm these findings (Fig. 12b, c). Note that the method remains directly applicable with no restriction to two-layered systems as long as permeability only varies in the transverse direction.

5 Discussion

The results reported here are applicable to immiscible, incompressible flow in layered porous media irrespective of material property contrasts, fluid property contrasts and length-scale, so long as capillary effects are negligible. Example applications for our models include plug-scale experiments in the laboratory using bead-packs (10’s cm scale), waterflooding of hydrocarbon reservoirs (100’s m scale) and \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage in regional aquifers (km scale). The results provide a framework to support mechanistic interpretations of complex field or experimental data, and numerical model predictions, through the use of simple dimensionless models. An approach to estimate and use the dimensionless scaling groups reported in this paper in realistic reservoir models is presented in a companion paper (Debbabi et al. 2018).

Our results clarify the roles played by the various buoyancy numbers previously introduced in the literature (see Shook et al. 1992 for a review). First, we demonstrate that the longitudinal and transverse buoyancy numbers can be used to predict the onset of longitudinal and transverse buoyancy effects, at \(N_{bv,L}=0.1\) and \(N_{bv,T}=0.1\), respectively. When the two effects are concurrently increased, by increasing \(N_{bv}\) while maintaining \(N_{\alpha }\) and \(R_L\) fixed, the purely geometrical dip angle group \(N_{\alpha }\) defines whether longitudinal or transverse buoyancy effects control changes in storage efficiency, when \(N_{\alpha }\) is large and small, respectively. This correlation is useful, for example, in dipping systems to rapidly predict how storage efficiency changes when the flow rate is varied. We also demonstrate that buoyancy effects can be significant with low values of \(N_{bv}\), as long as the longitudinal or transverse buoyancy numbers are large (\(>1\)), and that \(N_{bv}\) must be maintained \(<2\) to avoid back flow through the inlet face.

Our results demonstrate that dip-related buoyancy effects not only reduce the remaining displaced phase saturation in regions contacted by the injected phase, but also oppose the effects of permeability heterogeneity. This is not the case for buoyancy crossflow, which may either oppose or enhance the effects of permeability heterogeneity on fluid distribution depending on the layer ordering. This might explain why permeability heterogeneity has been found to have relatively little impact on gravity-stable gas or water injections in steeply dipping reservoirs (Kulkarni and Rao 2006).

We also suggest that breakthrough storage efficiencies obtained from the 1D fractional flow model applicable in the buoyancy-segregation limit can be used to compare and rank performances of geostatistical realizations in formations where vertical variations of permeability dominate over horizontal variations. This is the case in many clastic depositional environments (e.g. single or stacked barrier bars, shallow marine sheet sands, transgressive sands, offshore bars, braided rivers, aeolian deposits; see Weber and Van Geuns 1990 for a review). This performance measure complements the breakthrough storage efficiency estimated from the flow-storage (\(F-\Phi \)) capacity curve, which is valid in the viscous limit, and assumes the displacement is piston-like with unit mobility ratio (Lake 1989; Shook and Mitchell 2009).

6 Conclusions

We examined the downwards injection of a fluid which is less dense than the fluid in place along dipping layers of contrasting permeability. Two-phase flow was characterized using seven dimensionless parameters, five of which are independent, obtained from inspectional analysis of the flow equations (Table 1). The impact of the dimensionless numbers on flow was quantified in terms of a dimensionless storage efficiency, so results are directly applicable, regardless of scale, to geologic \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage, but can also be applied to gas flooding of hydrocarbon reservoirs using the numerically equivalent recovery efficiency. The symmetry of the problem also allows application of the results to waterflooding of hydrocarbon reservoirs by inverting the layer order.

Longitudinal buoyancy effects, quantified by the longitudinal buoyancy number \(N_{bv,L}\), increase storage efficiency by reducing the distance between the leading edges of the injected phase in each layer, in addition to decreasing the remaining displaced phase saturation behind the leading edge of the displacing phase. Longitudinal buoyancy effects become significant only when \(N_{bv,L}>0.1\).

The impact of buoyancy crossflow on fluid distribution and storage efficiency, quantified by the transverse buoyancy number \(N_{bv,T}\), depends on the layer ordering. When permeability increases upwards, injected phase buoyancy crossflow occurs from the low to the high permeability layer; this reduces storage efficiency. When permeability decreases downwards, injected phase buoyancy crossflow occurs from the high to the low permeability layer; this increases storage efficiency. Buoyancy crossflow becomes significant only when \(N_{bv,T}>0.1\).

When both longitudinal and buoyancy effects are concurrently increased, i.e. \(N_{bv}\) is varied but the other dimensionless groups are fixed, the purely geometrical dip angle group \(N_{\alpha }\) defines whether changes in storage efficiency are dominated by changes in the longitudinal (\(N_{\alpha }\) large) or transverse buoyancy effects (\(N_{\alpha }\) small).

In the buoyancy-segregation limit, the multiphase flow problem can be reduced to a 1D fractional flow model that allows rapid prediction of storage efficiency. The model presented accounts for both dip and layering, thereby generalizing earlier works that considered either of these only. The predicted storage efficiency may be used to compare and rank performances of geostatistical realizations, as long as transverse variations of permeability dominate over horizontal variations, as is the case in a wide range of clastic depositional environments.

Abbreviations

- BT:

-

Breakthrough time, [T]

- \(E_d\) :

-

Displacement efficiency

- \(E_s\) :

-

Storage efficiency

- \(E_{sw}\) :

-

Sweep efficiency

- \(f_b\) :

-

Buoyancy-limit fractional flow

- \(f_i\) :

-

Viscous-limit fractional flow

- H :

-

Layer thickness, [L]

- \(\overline{\overline{k}}\) :

-

Absolute permeability (diagonal) tensor, \({[L}^2]\)

- \(k_x\) :

-

Absolute longitudinal permeability, \([L^2]\)

- \(k_z\) :

-

Absolute transverse permeability, \({[L}^2]\)

- \(k_{r,i}\) :

-

Relative permeability of the injected phase

- \(k^e_{r,i}\) :

-

End-point relative permeability of the injected phase

- \(k_{r,d}\) :

-

Relative permeability of the displaced phase

- \(k^e_{r,d}\) :

-

End-point relative permeability of the displaced phase

- L :

-

Model length, [L]

- \(N_{\alpha }\) :

-

Dip angle group

- \(N_{bv}\) :

-

Buoyancy number

- \(N_{bv,L}\) :

-

Longitudinal buoyancy number

- \(N_{bv,T}\) :

-

Transverse buoyancy number

- \(M_e\) :

-

End-point mobility ratio

- \(n_d\) :

-

Corey exponent for the displaced phase relative permeability curve

- \(n_i\) :

-

Corey exponent for the injected phase relative permeability curve

- P :

-

Pressure, \([ML^{-1}T^{-2}]\)

- \({\overline{q}}_{in}\) :

-

Average volumetric influx per unit area, \([LT^{-1}]\)

- \(\mathbf {q}_\mathbf{i}\) :

-

Injected phase volumetric flux per unit area, \([LT^{-1}]\)

- \(\mathbf {q}_\mathbf{d}\) :

-

Displaced phase volumetric flux per unit area, \([LT^{-1}]\)

- \(\mathbf {q}_\mathbf{T}\) :

-

Total volumetric fluid flux per unit area, \([LT^{-1}]\)

- \(R_L\) :

-

Effective aspect ratio

- s :

-

Normalized injected phase saturation

- \(s_{av}\) :

-

Normalized average saturation behind the shock-front

- \(s_f\) :

-

Normalized shock-front saturation

- \(S_{i,r}\) :

-

Residual saturation for the injected phase

- \(S_{d,r}\) :

-

Residual saturation for the displaced phase

- \(\Delta S\) :

-

Moveable saturation

- \({\lambda }_i\) :

-

Injected phase mobility, \([LTM^{-1}]\)

- \({\lambda }_d\) :

-

Displaced phase mobility, \([LTM^{-1}]\)

- \({\lambda }_T\) :

-

Total mobility of the fluids, [\(LTM^{-1}]\)

- \({\mu }_i\) :

-

Injected phase viscosity, \([ML^{-1}T^{-1}]\)

- \({\mu }_d\) :

-

Displaced phase viscosity, \([ML^{-1}T^{-1}]\)

- \(\phi \) :

-

Porosity

- \({\rho }_j\) :

-

Density of phase \(j=i,\ d\), [\(ML^{-3}]\)

- \({\sigma }_x\) :

-

Absolute longitudinal permeability ratio

References

Ahmed, G., Castanier, L.M., Brigham, W.E.: An experimental study of waterflooding from a two-dimensional layered sand model. SPE Reserv. Eng. 3(01), 45–54 (1988). https://doi.org/10.2118/13599-PA

Aziz, K., Settari, A.: Petroleum Reservoir Simulation. Chapman & Hall, London (1979)

Campbell, C.V.: Lamina, laminaset, bed and bedset. Sedimentology 8(1), 7–26 (1967). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1967.tb01301.x

Cavanagh, A., Ringrose, P.: Simulation of \(\text{ CO }_2\) distribution at the In Salah storage site using high-resolution field-scale models. Energy Procedia 4, 3730–3737 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2011.02.306

C&C Reservoirs (2016) Digital analogs knowledge system (DAKS) database. http://www.ccreservoirs.com (accessed 09.08.16)

Choi, K., Jackson, M.D., Hampson, G.J., Jones, A.D., Reynolds, A.D.: Predicting the impact of sedimentological heterogeneity on gas-oil and water-oil displacements: fluvio-deltaic Pereriv Suite reservoir, Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli oilfield. South Caspian basin. Pet. Geosci. 17(2), 143–163 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1144/1354-079310-013

Christie, M., Blunt, M.: Tenth SPE comparative solution project: a comparison of upscaling techniques. In: SPE Reservoir Simulation Symposium, 11–14 February, Houston, TX, USA, Society of Petroleum Engineers (2001). https://doi.org/10.2118/66599-MS

Craig, F., Sanderlin, J., Moore, D., Geffen, T.: A laboratory study of gravity segregation in frontal drives. Trans. AIME 210, 275–282 (1957)

Dake, L.: Fundamentals of reservoir engineering (1983)

De Marsily, G., Delay, F., Teles, V., Schafmeister, M.: Some current methods to represent the heterogeneity of natural media in hydrogeology. Hydrol. J. 6(1), 115–130 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1007/s100400050138

Debbabi, Y., Jackson, M.D., Hampson, G.J., Fitch, P.J., Salinas, P.: Viscous crossflow in layered porous media. Transp. Porous Media 117(2), 281–309 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-017-0834-z

Debbabi, Y., Jackson, M.D., Hampson, G.J., Salinas, P.: Capillary heterogeneity trapping and crossflow in layered porous media. Transport in Porous Media pp 1–24, (2017) https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-017-0915-z

Debbabi, Y., Stern, D., Hampson, G.J., Jackson, M.D.: Use of dimensionless scaling groups to interpret reservoir simulation results. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 163, 270–282 (2018)

Deveugle, P.E., Jackson, M.D., Hampson, G.J., Farrell, M.E., Sprague, A.R., Stewart, J., Calvert, C.S.: Characterization of stratigraphic architecture and its impact on fluid flow in a fluvial-dominated deltaic reservoir analog: Upper Cretaceous Ferron Sandstone Member. Utah. AAPG Bull. 95(5), 693–727 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1306/09271010025

Deveugle, P.E., Jackson, M.D., Hampson, G.J., Stewart, J., Clough, M.D., Ehighebolo, T., Farrell, M.E., Calvert, C.S., Miller, J.K.: A comparative study of reservoir modeling techniques and their impact on predicted performance of fluvial-dominated deltaic reservoirs. AAPG Bull. 98(4), 729–763 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1306/08281313035

Dietz, D.: A theoretical approach to the problem of encroaching and by-passing edge water. Proceedings of the Akademie van Wetenschappen, Amsterdam, Netherlands 56–B, 83–92 (1953)

Ekrann, S.: An analysis of gravity-segregated piston-like displacement in stratified reservoirs. SPE Reserv. Eng. 7(01), 143–148 (1992). https://doi.org/10.2118/18598-PA

El-Khatib, N.A.: Waterflooding performance in inclined communicating stratified reservoirs. SPE J. 17(01), 31–42 (2012)

Fayers, F.J., Muggeridge, A.H.: Extensions to Dietz theory and behavior of gravity tongues in slightly tilted reservoirs. SPE Reserv. Eng. 5(04), 487–494 (1990). https://doi.org/10.2118/18438-PA

Gaucher, D., Lindley, D.: Waterflood performance in a stratified, five-spot reservoir—A scaled-model study. Trans. AIME 219, 208–215 (1960)

Graham, G.H., Jackson, M.D., Hampson, G.J.: Three-dimensional modeling of clinoforms in shallow-marine reservoirs: Part 1. Concepts and application. AAPG Bull. 99(6), 1013–1047 (2015)

Gunn, I., Woods, A.W.: On the flow of buoyant fluid injected into a confined, inclined aquifer. J. Fluid Mech. 672, 109–129 (2011)

Guo, B., Zheng, Z., Bandilla, K.W., Celia, M.A., Stone, H.A.: Flow regime analysis for geologic \(\text{ CO }_2\) sequestration and other subsurface fluid injections. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 53, 284–291 (2016)

Huppert, H.E., Neufeld, J.A., Strandkvist, C.: The competition between gravity and flow focusing in two-layered porous media. J. Fluid Mech. 720, 5–14 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1144/1354-079307-787

Ingsoy, P., Skjaeveland, S.: Experimental validation of a new method for optimizing miscible flooding of stratified reservoirs. In: SPE/DOE Enhanced Oil Recovery Symposium, 22–25 April, Tulsa, OK, USA, Society of Petroleum Engineers (1990). https://doi.org/10.2118/20241-MS

Jackson, M.D., Muggeridge, A.H., Yoshida, S., Johnson, H.D.: Upscaling permeability measurements within complex heterolithic tidal sandstones. Math. Geol. 35(5), 499–520 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026236401104

Jones, A., Doyle, J., Jacobsen, T., Kjønsvik, D.: Which sub-seismic heterogeneities influence waterflood performance? A case study of a low net-to-gross fluvial reservoir. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 84(1), 5–18 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1995.084.01.02

King, M., Mansfield, M.: Flow simulation of geologic models. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2(04), 351–367 (1999). https://doi.org/10.2118/57469-PA

Kjonsvik, D., Doyle, J., Jacobsen, T.: The effects of sedimentary heterogeneities on production from a shallow marine reservoir-what really matters? In: SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, 25–28 September, New Orleans, LA, USA, Society of Petroleum Engineers (1994). https://doi.org/10.2118/28445-MS

Koltermann, C.E., Gorelick, S.M.: Heterogeneity in sedimentary deposits: a review of structure-imitating, process-imitating, and descriptive approaches. Water Resour. Res. 32(9), 2617–2658 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1029/96wr00025

Kulkarni, M.M., Rao, D.N.: Characterization of operative mechanisms in gravity drainage field projects through dimensional analysis. In: SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, 24–27 September, San Antonio, TX, USA, Society of Petroleum Engineers (2006)

Lake, L.W.: Enhanced Oil Recovery. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs (1989)

Legler, B., Johnson, H.D., Hampson, G.J., Massart, B.Y., Jackson, C.A.L., Jackson, M.D., El-Barkooky, A., Ravnas, R.: Facies model of a fine-grained, tide-dominated delta: Lower Dir Abu Lifa Member (Eocene), Western Desert, Egypt. Sedimentology 60(5), 1313–1356 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12037

Massart, B.Y., Jackson, M.D., Hampson, G.J., Johnson, H.D., Legler, B., Jackson, C.A.L.: Effective flow properties of heterolithic, cross-bedded tidal sandstones: Part 1. Surface-based modeling. AAPG Bull. 100(5), 697–721 (2016)

Pegler, S.S., Huppert, H.E., Neufeld, J.A.: Fluid injection into a confined porous layer. J. Fluid Mech. 745, 592–620 (2014)

Permadi, A., Yuwono, I., Simanjuntak, A.: Effects of vertical heterogeneity on waterflood performance in stratified reservoirs: a case study in Bangko Field, Indonesia. In: SPE Asia Pacific Conference on Integrated Modelling for Asset Management, 29–30 March, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Society of Petroleum Engineers (2004). https://doi.org/10.2118/87016-MS

Peters, B.M., Zhou, D., Blunt, M.J.: Experimental investigation of scaling factors that describe miscible floods in layered systems. In: SPE/DOE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, 19–22 April, Tulsa, OK, USA, Society of Petroleum Engineers (1998). https://doi.org/10.2118/39624-MS

Richardson, J., Kerver, J., Hafford, J., Osoba, J.: Laboratory determination of relative permeability. J. Pet. Technol. 4(08), 187–196 (1952). https://doi.org/10.2118/952187-g

Ringrose, P., Sorbie, K., Corbett, P., Jensen, J.: Immiscible flow behaviour in laminated and cross-bedded sandstones. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 9(2), 103–124 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/0920-4105(93)90071-l

Shook, G.M., Mitchell, K.M.: A robust measure of heterogeneity for ranking earth models: The F-Phi curve and dynamic Lorenz coefficient. In: SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, 4–7 October, New Orleans, LA, USA, Society of Petroleum Engineers (2009). https://doi.org/10.2118/124625-MS

Shook, M., Li, D., Lake, L.W.: Scaling immiscible flow through permeable media by inspectional analysis. Situ 16, 311 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(93)91860-l

Stewart, J.S.: The interplay between viscous and gravity forces in two-phase stratified reservoir crossflow. In: 14th European Conference on the Mathematics of Oil Recovery, 8–11 September, Catania, Sicily, Italy, European Association of Geoscientists and Engineers (2014)

Tjølsen, C., Scheie, Å., Damsleth, E., Worthington, P., Longeron, D.: A study of the correlation between relative permeability, air permeability and depositional environment on the core-plug scale. Advances in Core Evaluation II, Reservoir Appraisal, pp 169–183 (1991)

Weber, K.: How heterogeneity affects oil recovery. In: Lake, L.W., Carroll, H.B. (eds.) Reservoir Characterization. Academic Press, Cambridge (1986)

Weber, K., Van Geuns, L.: Framework for constructing clastic reservoir simulation models. J. Pet. Technol. 42(10), 1–248 (1990)

Welge, H.J.: A simplified method for computing oil recovery by gas or water drive. J. Pet. Technol. 4(04), 91–98 (1952). https://doi.org/10.2118/124-G

White, C., Barton, M.: Translating outcrop data to flow models, with applications to the ferron sandstone. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2(4), 341–350 (1999). https://doi.org/10.2118/57482-PA

Wu, Y.S.: Virtual node method for handling well bore boundary conditions in modeling multiphase flow in porous and fractured media. Water Resour. Res. 36(3), 807–814 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1029/1999wr900336

Yortsos, Y.: A theoretical analysis of vertical flow equilibrium. Transp. Porous Media 18(2), 107–129 (1995)

Zheng, Z., Guo, B., Christov, I.C., Celia, M.A., Stone, H.A.: Flow regimes for fluid injection into a confined porous medium. J. Fluid Mech. 767, 881–909 (2015)

Zhou, D., Fayers, F., Orr Jr., F.: Scaling of multiphase flow in simple heterogeneous porous media. SPE Reserv. Eng. 12(03), 173–178 (1997). https://doi.org/10.2118/27833-pa

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the insightful comments of Dave Stern. ExxonMobil Upstream Research Company is thanked for funding the research and for granting permission to publish. TOTAL is thanked for partial support of Jackson under the TOTAL Chairs programme at Imperial College London. C&C Reservoirs is thanked for providing access to the Digital Analogs Knowledge System (DAKS) database, and permission to publish Figs. 3 and 4. We also acknowledge Schlumberger for providing the Eclipse simulator under an academic licence. Data may be obtained from the corresponding author on request (e-mail: yd2713@imperial.ac.uk).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Derivation of Governing Dimensionless Numbers

We follow here the methodology described by Debbabi et al. (2017a) and additionally account for buoyancy effects to obtain the set of dimensionless scaling groups presented in Table 1. The methodology is similar to the commonly termed “inspectional analysis”, which has been previously applied to homogeneous (Shook et al. 1992) and layered porous media (Zhou et al. 1997).

Inspectional analysis of the flow equations. Before non-dimensionalising the flow equations, we first express the governing flow Eqs. (1)–(4) within the so-called fractional flow formulation. This requires the injected phase volumetric flux per unit area to be expressed as a function of the total flux, i.e.

where \(f_i\) denotes the dimensionless ratio of the injected to the total fluid mobility \(f_i={\lambda }_i/{\lambda }_T\), which corresponds to the injected phase fractional flow in the viscous limit, and controls the efficiency with which the injected phase displaces the phase initially in place (see Debbabi et al. 2017a). Substituting the latter expression into the continuity equation (1) yields the following (dimensional) formulation of the governing flow equations

Normalizing flow equations using the dimensionless quantities \(\hat{x}=x/L\), \(\hat{z}=z/H\), \(\hat{t}=t{\overline{q}}_{in}/\overline{\phi \Delta S}L\), \({\hat{q}}_x=q_x/{\overline{q}}_{in}\), \({\hat{q}}_z=q_zL\ \overline{k_zk^e_{r,d}}\ /{\overline{q}}_{in}\ H\ \overline{k_xk^e_{r,d}}\), \({\widehat{\lambda }}^j_T={\lambda }^j_T/(k^{e,j}_{r,d}/{\mu }_d)\), \({\widehat{\lambda }}^j_i={\lambda }^j_i/(k^{e,j}_{r,d}/{\mu }_d)\) and \({\widehat{\lambda }}^j_d={\lambda }^j_d/(k^{e,j}_{r,d}/{\mu }_d)\) for \(j=1,\ 2\), \(\hat{P}=\overline{k_xk^e_{r,d}}\ (P-P_0)/L\ {\overline{q}}_{in}{\mu }_d\), \({\widehat{\rho }}_j={\rho }_j/\Delta \rho \) for \(j=i,\ d\), and \({\hat{k}}_{x,d}=k_xk^e_{r,d}/\overline{k_xk^e_{r,d}}\), we obtain the following dimensionless form of the governing equations

From these dimensionless flow equations, we identify the governing dimensionless numbers reported in Table 1 as constant coefficients appearing in the partial differential equations or constant coefficients controlling functionals appearing in the differential equations. The effective aspect ratio \(R_L,\) the longitudinal buoyancy number \(N_{bv,L}\) and the transverse buoyancy number \(N_{bv,T}\) directly appear as constant coefficients within the coupled partial differential equations. The end-point mobility ratio \(M_e=k^e_{r,i}{\mu }_d/k^e_{r,d}{\mu }_i\) and the Corey exponents, \(n_i\) and \(n_d\), are identified as a consequence of our relative permeability parameterization from

The spatially dependent functionals \({\hat{k}}_{x,d}\) is parameterized by the longitudinal permeability ratio \({\sigma }_x={\left( k_xk^e_{r,d}\right) }_1/{\left( k_xk^e_{r,d}\right) }_2\). We also report in Table 1 the buoyancy number \(N_{bv}=N_{bv,T}/R^2_L\), which we show in Appendix 2, determines whether the injection proceeds along the entire length of the inlet face (\(N_{bv}\le 2\)), and the dip angle group \(N_{\alpha }\), which we show in Sect. 4.3, determines whether changes in longitudinal or transverse buoyancy effects dominate changes in storage efficiency.

Appendix 2: No-Crossflow Limit

We now examine the no-crossflow limit (\(R_L=0\)) to (i) determine why increased longitudinal buoyancy effects reduce the distance between the leading edges of the injected phase in each layer without crossflow (Fig. 5), and (ii) identify conditions for which the injection cannot occur along the entire length of the inlet face.

We first analyse the impact of longitudinal buoyancy effects on the distance between the leading edges of the injected phase in the high and low permeability layers by computing the influxes into each layer. Integrating the total volumetric flux per unit area along the model, using the incompressibility equation

obtained with \(R_L=0\), yields the total volumetric flux per unit area (normalised by the total fluid mobility) as

where \(\overline{{\lambda }_T}\) denotes the (harmonic) average of the dimensionless total mobility \({\widehat{\lambda }}_T\) along the model, and \(\overline{\rho }\) the (arithmetic) average of the dimensionless, fractional flow-weighted density \(f_i{\widehat{\rho }}_i+(1-f_i){\widehat{\rho }}_d\) along the model. This expression shows that the total volumetric influx per unit area varies along the inlet face in response to fluid density changes, in addition to the fluid mobility changes previously considered (Debbabi et al. 2017a). This is a consequence of the uniform potential boundary condition. As the injection proceeds, the average fluid density \(\overline{\rho }\) decreases in both layers, but faster in the high permeability layer because this layer receives more influx. This uneven allocation of influxes therefore reduces the contribution of gravity effects to flow faster in high than low permeability layers. This reduces the velocity with which the injected phase propagates relative to the velocity achieved in low permeability layers. The leading edges of the injected phase are thereby closer with than without fluid density contrasts (see Fig. 5).

We now identify conditions at which the injection cannot proceed along the entire length of the inlet face. This is achieved by examining the sign of the total volumetric flux profile along the inlet face in the simplified case of a unit mobility ratio piston-like displacement with neither dip (\(N_{\alpha }=N_{bv,L}=0\)) nor permeability heterogeneity (\({\sigma }_x=1\)). Using the uniform potential boundary conditions, Eq. (24) can be simplified in this case as

where the longitudinal pressure drop at the base of the system \(\Delta \hat{P}\ \left( \hat{z}=0\right) \) is constrained by the unit average total influx,

This allows the total volumetric fluid flux per unit area along the inlet face to be expressed as a function of the dimensionless elevation \(\hat{z}\), i.e.

From Eq. (27) it can be seen that the inlet flux is negative across lower parts for \(N_{bv}>2\), in which case injection cannot occur.

Appendix 3: Derivation of Equivalent 1D Transverse Equilibrium Flow Model

We demonstrate in this appendix that, in the limit of large transverse buoyancy numbers \(N_{bv,T}\), there cannot be simultaneous flow of the two phases, and that the two-phase flow problem can be reduced to tracking the thickness h of the buoyancy tongue that preferentially sweeps the top of the system (see Fig. 13).

Examination of the dimensionless transverse injected phase flux, which is identified from Eq. (19),

indicates that, in the limit of \(N_{bv,T}\rightarrow \infty \), the product \(f_i\ {\widehat{\lambda }}_d\) is equal to zero because both the transverse injected phase and total flux, \({R^2_L\ \hat{q}}_{i,z}\) and \({R^2_L\ \hat{q}}_{i,z}\), are bounded. Hence, \(s=0\) or 1, i.e. flow is segregated.

In the limit of large effective aspect ratio \(R_L\), the dimensionless incompressibility equation (20) shows that the total flux in the transverse direction does not vary with the elevation \(\hat{z}\), i.e.

and is zero, due to the no-flux boundary conditions at \(\hat{z}=0\) and 1. This yields the transverse pressure gradient

From the segregation condition (\(s=0\) or 1), the pressure can be decomposed as a reference pressure \({\hat{P}}_r(\hat{x},\ \hat{z}=1,\hat{t})\) taken along the top boundary that is corrected by a hydrostatic pressure gradient as

when \(\hat{z}\ge 1-\hat{h}\), and

when \(\hat{z}\le 1-\hat{h}\). We can now eliminate pressure from the reduced system of equations by using conservation of mass in transverse cross sections of the system. This first requires the dimensionless longitudinal displacing and displaced phase fluxes

to be expressed as a function of the reference pressure \({\hat{P}}_r\),

By mass conservation through transverse cross sections, we have

which yields the longitudinal reference pressure gradient

and the total injected phase flux through a cross section

The injected phase mass conservation equation can be written as

where \(f_b\) is the fractional flow term reported in Eq. (15).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Debbabi, Y., Jackson, M.D., Hampson, G.J. et al. Impact of the Buoyancy–Viscous Force Balance on Two-Phase Flow in Layered Porous Media. Transp Porous Med 124, 263–287 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-018-1063-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-018-1063-9