Abstract

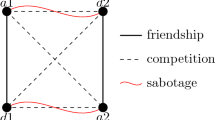

This paper investigates a two-player contest with a multiplicative sabotage effect, showing it can be converted into a standard Tullock contest with a nonlinear, endogenous cost function. We prove the existence and uniqueness of a pure strategy equilibrium. Our findings suggest that sabotage activities can be more pronounced when the productivity difference between players is small, and the more productive player might not necessarily undergo more attacks. Lazear and Rosen (1981) first-best outcome is attainable for symmetric players if sabotage is sufficiently ineffective or costly. When it is unattainable, optimal pay difference induces positive sabotage only if sabotage is ineffective but relatively inexpensive. Optimal pay difference decreases with effectiveness and increases with the marginal cost of destructive effort, exhibiting a non-monotonic relationship with productive-effort effectiveness. This non-monotonicity contrasts with the monotonicity of the first best pay difference when sabotage is infeasible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In addition, Corral et al. (2010) found the empirical evidence that more able teams may sabotage more in soccer games based on a rule change in Spanish football as a natural experiment, which is consistent with our findings.

Throughout the paper, by convergence, we mean that one player’s productive effort cost moves closer to the other’s while the latter is fixed.

The non-monotonicity of productive effort with respect to its effectiveness and the intuition behind it has been thoroughly discussed by Wang (2010).

One should note that our model is much more specific than that of Lazear and Rosen (1981), if sabotage was removed from our model. Our point here is not about how general these results are, but rather, about the possible impact of introducing sabotage in the model.

It should be noted that this interesting result showing that tolerating sabotage can sometimes be better than eliminating it can be partly attributable to the fact that the only instrument available for the principal in our setup is pay difference. If, in addition to the pay difference, the productive and destructive effort costs can be endogenously altered, the use of pay difference to induce the optimal outcome becomes less necessary; although obviously in such a case we must also consider the costs incurred in altering both productive and destructive effort costs.

Lazear (1989) acknowledged that there is no guarantee that a unique interior solution exists.

We will refer this result as pay compression in later discussion.

Gürtler et al. (2013) also showed that the problem of reduction in productive effort due to the risk of being sabotaged by competitors is solvable by concealing intermediate information on the relative performance of players.

Instead of using the rank-order tournament as the incentive device, other types of contracts, such as piece rate, can also be used as incentive devices. While a piece rate contract may be optimal under some circumstances, a tournament contract may be optimal in other circumstances, particular in the case where players are intrinsically motivated by the desire to be ahead of their peer and the benefits obtained from winning the tournament (e.g. Sheremeta (2016)). Although comparing the tournament contract and the piece rate contract is interesting, it is beyond the scope of this paper. In this paper, rather than designing an optimal labor contract, we focus on analysing the properties of the widely used rank-order tournament. Please see also Lazear and Rosen (1981) for discussions on optimal labor contracts.

Lazear (1989) used a general form of production function. The cost of doing so is that he has to assume the existence and uniqueness of symmetric equilibrium.

Details are provided in Section B.4 of the Online Appendix.

A player cannot win the competition by only exerting destructive effort is a reasonable assumption. This is because even when one party wins an election by attacking the opponent, the winner still needs to demonstrate the voters what are his beliefs and what he hopes to achieve if being elected.

Their papers adopt a setting with at least three players. In Sections B.8.3 and B.8.4 of the Online Appendix, we show that the same insight holds for two-player settings.

To have explicit solutions for \(x^{*}\) and \(s^{*}\), we do not need to put any restrictions on \(c_{i}\) and \(c_{j}\).

It is important to note that the losing prize established by the principal can be less than zero, and hence players are not subject to the limited liability constraints. For instance, in many contests, contestants need to pay a non-refundable participation fee.

References

Amegashie, J. (2012). Productive versus destructive efforts in contests. European Journal of Political Economy, 28, 461–468.

Amegashie, J. A. (2015). Sabotage in contests. In R. D. Congleton & A. L. Hillman (Eds.), Companion to the political economy of rent seeking, chapter 9 (pp. 138–149). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Amegashie, J., & Runkel, M. (2007). Sabotaging potential rivals. Social Choice and Welfare, 28(1), 143–162.

Arbatskaya, M., & Mialon, H. (2010). Multi-activity contests. Economic Theory, 43, 23–43.

Baker, G., Gibbs, M., & Holmstrom, B. (1994). The internal economics of the firm: Evidence from personnel data. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(4), 881–919.

Balafoutas, L. (2012). Sabotage in tournaments: Evidence from a natural experiment. Kyklos International Review for Social Sciences, 65(4), 425–441.

Carpenter, J. P., Matthews, P. H., & Schirm, J. (2007). Tournaments and office politics: Evidence from a real effort experiment. American Economic Review, 100(1), 504–517.

Charness, G., Masclet, D., & Villeval, M. C. (2014). The dark side of competition for status. Management Science, 60(1), 38–55.

Chen, K.-P. (2003). Sabotage in promotion tournaments. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 19(1), 119–140.

Chen, K.-P. (2005). External recruitment as an incentive device. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(2), 259–277.

Chowdhury, S. M., & Gürtler, O. (2015). Sabotage in contests: A survey. Public Choice, 164(1–2), 135–155.

Cornes, R., & Hartley, R. (2005). Asymmetric contests with general technologies. Economic theory, 26(4), 923–946.

Corral, J., Prieto-Rodríguez, J., & Simmons, R. (2010). The Effect of Incentives on Sabotage: The Case of Spanish Football. Journal of Sports Economics, 11(3), 243–260.

Dato, S., & Nieken, P. (2014). Gender differences in competition and sabotage. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 100(1), 64–80.

Eriksson, T. (1999). Executive compensation and tournament theory: Empirical tests on Danish data. Journal of Labor Economics, 17(2), 262–280.

Franceschelli, I., Galiani, S., & Gulmez, E. (2010). Performance pay and productivity of low- and high-ability workers. Labour Economics, 17(2), 317–322.

Fu, Q., & Lu, J. (2012). Micro foundations of multi-prize lottery contests: A perspective of noisy performance ranking. Social Choice and Welfare, 38(3), 497–517.

Gürtler, O. (2008). On sabotage in collective tournaments. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 44(3–4), 383–393.

Gürtler, J. D. O. (2015). Strategic shirking in promotion tournaments. International Game Theory Review, 7(2), 211–228.

Gürtler, O., & Münster, J. (2010). Sabotage in dynamic tournaments. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 46(2), 179–190.

Gürtler, O., & Münster, J. (2013). Rational self-sabotage. Mathematical Social Sciences, 65(1), 1–4.

Gürtler, O., Münster, J., & Nieken, P. (2013). Information policy in tournaments with sabotage. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 115(3), 932–966.

Harbring, C., & Irlenbusch, B. (2008). How many winners are good to have? On tournaments with sabotage. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 65(3–4), 682–702.

Harbring, C., & Irlenbusch, B. (2011). Sabotage in tournaments: Evidence from a laboratory experiment. Management Science, 57(4), 611–627.

Hirshleifer, J., & Riley, J. (1992). The analytics of uncertainty and information, 1992. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ishida, J. (2012). Dynamically sabotage-proof tournaments. Journal of Labor Economics, 30(3), 627–655.

Jue, N (2012). Four major flaws of force ranking. I4CP The Productivity Blog http://www.i4cp.com/productivity-blog/2012/07/16/four-major-flaws-of-force-ranking.

Konrad, K. (2000). Sabotage in rent-seeking contests. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 16(1), 155.

Kräkel, M., & Müller, D. (2012). Sabotage in teams. Economics Letters, 115(2), 289–292.

Lazear, E. P. (1989). Pay equality and industrial politics. Journal of Political Economy, 97(3), 561–580.

Lazear, E., & Rosen, S. (1981). Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 841.

Münster, J. (2007). Selection tournaments, sabotage, and participation. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 16(4), 943–970.

Nti, K. (2004). Maximum efforts in contests with asymmetric valuations. European journal of political economy, 20, 1059–1066.

Ovide, S (2013). Microsoft abandons ‘stack ranking’ of employees: Software giant will end controversial practice of forcing managers to designate stars, underperformers. The Wall Street Journal, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303460004579193951987616572.

Pérez-Castrillo, J. D., & Verdier, T. (1992). A general analysis of rent-seeking games. Public Choice, 73(3), 335–350.

Sheremeta, R. (2016). The Pros and Cons of Workplace Tournaments: Tournaments can Outperform Other Compensation Schemes such as Piece Rate and FIxed Wage Contract. IZA World of Labor, 302, 10.

Skaperdas, S., & Grofman, B. (1995). A modeling negative campaigning. American Political Science Review, 89, 49–61.

Szidarovszky, F., & Okuguchi, K. (1997). On the existence and uniqueness of pure nash equilibrium in rent-seeking games. Games and Economic Behavior, 18(1), 135–140.

Tran, A., & Zeckhauser, R. (2012). Rank as an inherent incentive: Evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 96(9), 645–650.

Wang, Zhe. (2017) A comparison between rank-order contests and piece rate contracts: Theory and evidence in the case with sabotage. Working paper.

Wang, Z. (2010). The optimal accuracy level in asymmetric contests. Journal of Theoretical Economics, 10(1), 13.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank J. Atsu Amegashie, Subhasish Chowdhury, Qiang Fu, Oliver Gürtler, Kai Konrad, Dan Kovenock, Wolfgang Leininger, Johannes Münster, Stergios Skaperdas, Alberto Vesperoni, Dazhong Wang, Zhewei Wang, Jun Zhang, Jie Zheng and the audience at the 2015 CBESS Conference on Contests at University of East Anglia, the 2016 International Conference of Western Economic Association International, the 2016 China Meeting of Econometric Society and 2017 SCNU Workshop on Microeconomic Theory and Experiment for helpful comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are ours.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Lu, J., Riyanto, Y.E. et al. Contests with multiplicative sabotage effect. Theory Decis (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-024-09983-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-024-09983-x