Abstract

This paper discusses the ability of explanationist theories of epistemic justification to account for the justification we have for holding beliefs about the future. McCain’s explanationist account of the relation of evidential support is supposedly in a better position than other theories of this type to correctly handle cases involving beliefs about the future. However, the results delivered by this account have been questioned by Byerly and Martin. This paper argues that McCain’s account is, in fact, able to deliver plausible results in cases involving such beliefs and that explanationism, if properly articulated, is illuminating with respect to the justification we have for holding such beliefs, as it manages to correctly distinguish evidence that only supports believing probabilistic claims about the future from evidence that is sufficient to believe that a particular event will happen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Conee and Feldman (2008) endorse such a view.

The problem for explanationism is, therefore, more general than cases involving beliefs about the future. But as this problem is particularly salient in such cases, the debate has tended to focus on the issue of beliefs concerning future events. Note, however, that any solution that can show how explanationism can correctly handle beliefs about the future will generalize to other cases as well (thanks to an anonymous referee for pointing this out).

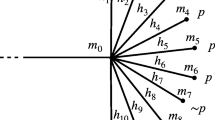

p is an explanatory consequence of the best explanation for why S has e iff p, if true, would be better explained by the best explanation for why S has e than \( \neg \)p, if true, would be.

One might object that an explanation containing the proposition ‘most golf balls rolling toward the cup in circumstances C have a chance to go into the cup (significantly) higher than 50%’ is an equally good explanation of the golfer’s observations. After all, this proposition could also contribute to explaining why the golfer observed that most golf balls that have rolled toward the cup in circumstances C have gone into the cup. Note that this constitutes an objection only if ‘most golf balls rolling toward the cup in circumstances C have a chance to go into the cup (significantly) higher than 50%’ entails that a minority of the golf balls rolling toward the cup in circumstances C have a chance to go into the cup lower than 50%. Otherwise, this proposition is equivalent to the proposition ‘all golf balls rolling toward the cup in circumstances C have a chance to go into the cup higher than 50%’. It is, however, doubtful that an explanation which entails that a minority of the golf balls rolling toward the cup in circumstances C have a chance to go into the cup lower than 50% is an equally good explanation. If the golfer simply observed that most golf balls that have rolled toward the cup in circumstances C have gone into the cup, there is no reason to suppose that a minority of golf balls rolling toward the cup in these circumstances have a chance to go into the cup lower than 50%. An explanation stating that all golf balls rolling toward the cup in these circumstances have a chance to go into the cup higher than 50% is by far the simplest explanation of the golfer’s observations.

While many philosophers claim that a distinction should be made between statistical evidence and non-statistical evidence, there is no agreement among them concerning the features that make some evidence non-statistical as opposed to statistical. For possible accounts of non-statistical evidence see: Cohen (1977), Thomson (1986), Dant (1989), Pardo and Allen (2008), Enoch et al. (2012), Smith (2016, 2017) and Blome-Tillmann (2017).

Incidentally, Dant (1989) as well as Pardo and Allen (2008) underline the importance of inferences to the best explanation for legal standards of proof to argue that, typically, one is not entitled to perform such inferences on the basis of statistical evidence alone if the inferred proposition consists of a non-probabilistic claim.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for suggesting this case.

References

Blome-Tillmann, M. (2017). ‘More Likely Than Not’ knowledge first and the role of bare statistical evidence in courts of law. In A. Carter, E. Gordon, & B. Jarvis (Eds.), Knowledge first. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buchak, L. (2014). Belief, credence, and norms. Philosophical Studies,169, 285–311.

Byerly, R. (2013). Explanationism and justified beliefs about the future. Erkenntnis,78, 229–243.

Byerly, R., & Martin, K. (2015). Problems for explanationism on both sides. In Erkenntnis (Vol. 80, pp. 773–791).

Byerly, R., & Martin, K. (2016). Explanationism, super-explanationism, ecclectic explanationism: persistent problems on both sides. Logos & Episteme,7, 201–213.

Cohen, L. J. (1977). The probable and the provable. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Conee, E., & Feldman, R. (2008). Evidence. In Q. Smith (Ed.), Epistemology: New essays (pp. 83–104). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dant, M. (1989). Gambling on the truth: The use of purely statistical evidence as a basis for civil liability. 22 Columbia Journal of Law and Social Problems,31, 31–70.

Enoch, D., Spectre, L., & Fisher, T. (2012). Statistical evidence, sensitivity, and the legal value of knowledge. Philosophy & Public Affairs,40, 197–224.

Goldman, A. (2011). Toward a synthesis of reliabilism and evidentialism? Or: Evidentialism’s troubles, reliabilism’s rescue package. In T. Dougherty (Ed.), Evidentialism and its discontents (pp. 254–280). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kaplan, M. (1996). Decision theory as philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lehrer, K. (1974). Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCain, K. (2013). Explanationist evidentialism. Episteme,10, 299–315.

McCain, K. (2014a). Evidentialism, explanationism, and beliefs about the future. Erkenntnis,79, 99–109.

McCain, K. (2014b). Evidentialism and epistemic justification. New York: Routledge.

McCain, K. (2015). Explanationism: Defended on all sides. Logos & Episteme,6, 61–73.

McCain, K. (2017). Undaunted explanationism. Logos & Episteme,8, 117–127.

Nelkin, D. (2000). The lottery paradox, knowledge, and rationality. Philosophical Review,109, 373–409.

Pardo, M. S., & Allen, R. J. (2008). Juridical proof and the best explanation. Law and Philosophy,27, 223–268.

Schauer, F. (2003). Profiles, probabilities, and stereotyping. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Smith, M. (2016). Between probability and certainty: What justifies belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, M. (2017). When does evidence suffice for conviction? Mind, fzx026. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzx026.

Thomson, J. J. (1986). Liability and individualized evidence. Law and Contemporary Problems,49, 199–219.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Professors Gianfranco Soldati, Fabian Dorsch (1974–2017), Marcel Weber and two anonymous referees from this journal for comments on earlier drafts of this paper. This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Belkoniene, M. What should we believe about the future?. Synthese 197, 2375–2386 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1789-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1789-5