Abstract

Teachers are pivotal in creating safe and efficacious learning environments for ethnic minority students. Research suggests that teachers’ multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, and wellbeing at work may all play important roles in this endeavor. Using survey data on 433 teachers in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, the present study used structural equation models to analyze the paths between teachers’ multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing (work dedication and exhaustion), and whether self-efficacy mediates these paths. We further investigated how these associations differ between teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students versus teachers of multi-ethnic mainstream classes. The results show that positive multicultural attitudes were directly associated with high level of work dedication, but not with work exhaustion. Self-efficacy mediated the association between multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing, indicated by both higher work dedication and lower work exhaustion. Concerning the role of teacher’s class type, self-efficacy mediated the association between positive multicultural attitudes and work dedication for both types of teachers, whereas the mediation to low work exhaustion was only evident in mainstream class teachers. To conclude, teachers’ multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing are mediated by self-efficacy and this important link should be acknowledged when designing professional development programs in order to create supportive and competent learning environments for all students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In today’s increasingly multicultural schools, the role of the teacher is pivotal in supporting the wellbeing of and enabling a productive learning environment for all students. Migrant students, however, often feel less satisfaction and belonging in schools (Rodríguez et al., 2020; Wang, 2021). They are also susceptible to lower teacher expectations (Bates & Glick, 2013; Glock et al., 2013), leading to lower school performance and underachievement (de Boer et al., 2010; OECD, 2012). Teachers’ multicultural attitudes may potentially attenuate this inequality between migrant students and their peers (Celeste et al., 2019). Positive attitudes can be defined as the appreciation of cultural pluralism in the classroom, based on sensitivity and awareness of diversity of students’ cultural and ethnic backgrounds and their impact on learning and teaching (Abacioglu et al., 2020; Ponterotto et al., 1998). Multicultural attitudes are embedded in the broader multiculturalist approach to teaching, emphasizing diversity as an added value in the classroom (Abacioglu et al., 2019; Celeste et al., 2019), which makes positive attitudes a prerequisite to practicing culturally competent teaching (Cherng & Davis, 2019).

Multicultural attitudes also bear importance for quality of teaching and teachers’ work-related wellbeing in multicultural classrooms. Multiculturalist approaches have been found to be associated with higher self-efficacy, enthusiasm, and less burnout in teaching migrant students (Gutentag et al., 2018; Hachfeld et al., 2015). Teachers’ positive multicultural attitudes, high work engagement and self-efficacy are further related to better student performance and satisfaction (Bakker & Bal, 2010; Darling-Hammond & Youngs, 2002; Schachner et al., 2019). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion, on the other hand, has been found to be associated with lower instructional quality, which is in turn associated with lower student outcomes such as self-concept, interest, and achievement (Klusmann et al., 2022). Interestingly, teachers’ emotional exhaustion is even more strongly related to low student achievement in classes with high percentage of language minority students (Klusmann et al., 2016).

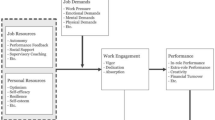

To date, available studies have focused on single associations between teachers’ cultural attitudes, beliefs or preferences, and their work-related self-efficacy and wellbeing. The present study applies a more comprehensive approach in modelling self-efficacy as a mediator between multicultural attitudes and wellbeing, as it can be considered as an important mediator with both theoretical (Bandura, 1977) and empirical importance. Further, the present study conceptualizes teachers’ work-related wellbeing through both negative (burnout) and positive (work engagement) aspects. Figure 1 illustrates the schematic model of associations between teachers’ multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, and wellbeing.

1.1 Teacher multicultural attitudes and self-efficacy

Studies on teacher multiculturality have incorporated several different but largely overlapping concepts, such as the multiculturalist approach, multicultural awareness, and multicultural attitudes. They reflect various emotional, attitudinal, and interactional aspects and willingness to learn about cultural diversity and applying the knowledge to teaching (Abacioglu et al., 2019; Celeste et al., 2019).

Drawing from Bandura’s social learning theory (1977), teacher self-efficacy can be defined as the belief that the teacher can induce desirable student outcomes, even with the unmotivated students (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001; for a review, see Zee & Koomen, 2016). According to Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001), self-efficacy includes the concepts of student engagement, instructional strategies, and classroom management. Together these depict the extent to which teachers can motivate their students and induce trust in students’ capacity to succeed in schoolwork, the extent of flexibility and creativity a teacher can apply in assessing and teaching their students, and the teacher practices that enable students to adhere to class rules and maintain calm and productive behavior.

Research suggests that teachers, in general, show lower levels of self-efficacy when teaching ethnic minority students compared to teaching students from their own ethnic group (Geerlings et al., 2018). Teacher multicultural attitudes have turned out to be important for self-efficacy. Studies show that negative cultural perceptions and stereotypes can decrease teacher self-efficacy or trust in the ability to enhance migrant students’ engagement and learning (Chwastek et al., 2021; Gutentag et al., 2018; Tatar et al., 2011), whereas the positive multiculturalist approach is associated with increased teaching self-efficacy (Sela-Shayovitz & Finkelstein, 2020). Teachers with positive multicultural perceptions also implement more effective strategies in their classroom management and student motivation (Abacioglu et al., 2019). Mastery experiences and satisfaction with one’s success in teaching, are believed to be the strongest source of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007). Researchers also emphasize that teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching cultural and ethnic minority students is not static, but it can be strengthened through teacher training in culturally sensitive practices (Choi & Lee, 2020; Choi & Mao, 2021; Parkhouse et al., 2019).

1.2 Teacher multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing

In this study, we conceptualize teachers’ wellbeing at work through both stress-related negative and motivation-related positive aspects: burnout and work engagement (Demerouti et al., 2001; Hakanen et al., 2006). Maslach et al. (2001) define burnout as the prolonged response to chronic stressors, involving dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. We examine teacher burnout through the dimension of work exhaustion, as it is stated as the central quality of burnout, specifically delineating the stress experienced as lack of emotional and physical resources and the feeling of being overburdened (Maslach et al., 2001). Cynicism and inefficacy would in turn depict indifference and lack of accomplishment related to work (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004).

Work engagement, or the positive and fulfilling disposition to work, involves the dimensions of dedication, vigor, and absorption (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Schaufeli et al., 2002). In this study, we define work engagement through the dimension of dedication, that is characterized by perceiving one’s work as significant, inspirational, challenging, and provoking enthusiasm and pride in one’s work (Schaufeli et al., 2002), thus giving it a rather affective nature. Vigor and absorption, in turn, refer to the energy invested and the pleasant immersion into one’s work (Schaufeli et al., 2002).

Research suggests that, in general, high job demands such as workload or emotional demands, form a special risk to burnout (Demerouti & Bakker, 2011; Hakanen et al., 2006). In contrast, high levels of job resources, such as organizational support, are associated with increased work engagement (Bermejo-Toro et al., 2015; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) and lack of them with burnout (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). In multicultural school contexts, job demands may entail, for example, the need to adapt teaching for different cultural groups without proper training or the role conflict of balancing between a pedagogue and a provider of care (Häggström et al., 2020; Parkhouse et al., 2019; Vera et al., 2012). Resources, on the other hand, can include both personal resources such as self-efficacy in teaching migrant students and job-related resources such as school climate that truly engages with multicultural values (Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003; Vera et al., 2012).

Research is not, however, unanimous about whether negative multicultural attitudes are linearly associated with high burnout. Research has applied the concept of diversity-related burnout referring to demands and burdens in teaching students with various ethnic and cultural backgrounds (Dubbeld et al., 2019; Tatar & Horenezyk, 2003). Studies have also conceptualized teachers’ disposition to multiculturality according to their assimilative versus multicultural approaches, the former discouraging and the latter enhancing cultural sensitivity, awareness of ethno-cultural differences, and positive attitudes to ethno-cultural diversity (Celeste et al., 2019). Some studies show that teachers who hold assimilative attitudes and see ethnic minority students as needing to adapt to majority culture have higher levels of diversity-related burnout (Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003), whereas other studies have not found an association between assimilative versus multicultural approach and burnout (Dubbeld et al., 2019). Interestingly, however, in multicultural and multi-ethnic schools, teachers who hold multicultural approaches or perceive their students as more teachable, showed lower levels of diversity-related burnout or exhaustion (Amitai et al., 2020; Gutentag et al., 2018).

We could not find research on the association between teachers’ multicultural attitudes and work engagement. Yet, available studies have conceptualized positive disposition to work as enthusiasm that is close to our assessment of dedication, both revealing the affective nature of work engagement (González-Romá et al., 2006). A few studies suggest that teachers’ negative cultural beliefs and stereotypes are associated with reduced enthusiasm at work (Chwastek et al., 2021), whereas the multicultural approach is associated with increased work enthusiasm (Hachfeld et al., 2015). It thus seems that teachers’ disposition to and attitudes of multiculturality play an important role for both teachers’ burnout and engagement in multicultural classrooms.

Additionally, teachers’ age and gender have been suggested to influence teachers’ wellbeing at work (Brunsting et al., 2014; Klassen & Chiu, 2010; Klassen et al., 2012; Topchyan & Woehler, 2021). The findings related to these personal characteristics are, however, mixed. While some studies suggest younger teachers with less experience to be more prone to experiencing burnout (Antoniou et al., 2006; Brunsting et al., 2014; Schwarzer & Hallum, 2008), others have found no effects of age or years of teaching experience (Hakanen et al., 2006). Some studies on work engagement have found weak signs of a positive association to age, but the results remain inconclusive (Klassen et al., 2012; Schaufeli et al., 2006; Topchyan & Woehler, 2021). The effect of gender on burnout and work engagement remains equally mixed. Some studies suggest female teachers (Antoniou et al., 2006; Klassen & Chiu, 2010), while others propose male teachers to be more prone to burnout (Brunsting et al., 2014). Further, other studies do not support the existence of gender differences in burnout (Hakanen et al., 2006; Hultell & Gustavsson, 2011; Pas et al., 2012). Likewise for work engagement, research on teacher gender has not shown unequivocal results (Klassen et al., 2012; Schaufeli et al., 2006; Topchyan & Woehler, 2021).

1.3 Teacher self-efficacy and work-related wellbeing

Ample evidence confirms that teacher self-efficacy is pivotal to many aspects of work-related wellbeing. Teachers showing high self-efficacy report less burnout (Egyed & Short, 2006; Schwarzer & Hallum, 2008; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007, 2014; Zee & Koomen, 2016) and higher levels of work engagement (Granziera & Perera, 2019; Li et al., 2017; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2014; Vera et al., 2012; Zee & Koomen, 2016).

Earlier studies thus evidence the importance of teacher multicultural attitudes on both work-related self-efficacy and wellbeing, and self-efficacy associating with wellbeing (Gutentag et al., 2018; Hachfeld et al., 2015; Sela-Shayovitz & Finkelstein, 2020). Yet, none of the studies have depicted the specific roles of each component, but merely concentrated on the direct effects of multicultural attitudes on self-efficacy and wellbeing.

1.4 Role of class type in multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, and wellbeing

Previous research suggests that the proportion of migrant or ethnic minority students in a classroom may affect teachers’ multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, and work-related wellbeing. Teachers of classes with higher proportion of ethnic minority students report more multicultural awareness and more positive attitudes (Abacioglu et al., 2019; Acquah et al., 2019), more self-efficacy (Geerlings et al., 2018) and more enthusiasm at work (Glock et al., 2019). Further, whereas Tatar and Horenczyk (2003) found that teachers in classrooms with low proportion of ethnic minority students show high diversity-related burnout, Amitai et al. (2020) on the contrary suggest that teachers in classrooms with higher proportion of ethnic minority students report more exhaustion. It thus seems that a greater proportion of ethnic minority students in schools and more frequent daily encounters may increase teachers’ positive multicultural attitudes, work engagement and self-efficacy, but also affect their work-related burnout and exhaustion. Researchers argue that positive developments are possible when school policies support teachers to be prepared to face the specific needs of ethnic minority students (Amitai et al., 2020; Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003).

Earlier studies have focused on how the proportion of migrant students in the classroom affects teachers’ multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, and work-related wellbeing, but we sought to understand also the qualitative differences between reception classes for migrant and refugee students and multi-ethnic mainstream education classes, and how they may be played out in these associations. While teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students are more focused on integration and language acquisition of their students, teachers of multi-ethnic mainstream classes have a greater focus on the curriculum. Further, reception classes for migrant and refugee students welcome the newly arrived refugee students, who can be especially vulnerable to severe mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety due to their past traumatic experiences and current migration stress (Kien et al., 2019; Spaas et al., 2021). Parents of refugee students are often burdened by uncertainty concerning families’ residence permits and security, which can negatively affect children’s school belonging and learning as they may worry about the prospects of continuing school in the new country. These vulnerabilities and special demands of students in the reception classes for migrant and refugee students might pose heightened requirements for teaching practices and care provisions that should be provided by teachers of these classes.

1.5 Aims of the study

In this study, we examine how teachers’ multicultural attitudes are associated with self-efficacy and work-related wellbeing (work exhaustion and dedication), and whether self-efficacy mediates the association between teacher multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing. We pose the following research questions (RQ) and hypotheses (H):

RQ1: How do teachers’ multicultural attitudes associate with their wellbeing at work, defined through work exhaustion and dedication?

H1: Based on previous research evidence (Gutentag et al., 2018; Hachfeld et al., 2015), we hypothesize that teachers’ positive multicultural attitudes are associated with high wellbeing at work, indicated by a low level of work exhaustion and a high level of work dedication.

RQ2: Does self-efficacy mediate the association between multicultural attitudes and wellbeing at work?

H2: We hypothesize that teacher self-efficacy mediates the association so that positive multicultural attitudes are associated with high self-efficacy, which in turn is associated with high wellbeing (high work dedication and low work exhaustion). This assumption is based on studies by Egyed and Short (2006), Granziera and Perera (2019), Sela-Shayovitz and Finkelstein (2020), and Zee and Koomen (2016).

RQ3: Do the hypothesized associations between multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy and work-related wellbeing differ between teachers of multi-ethnic mainstream education and teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students?

H3: In line with the studies by Abacioglu et al. (2019), Geerlings et al. (2018), and Glock et al. (2019), we hypothesize that the class type (multi-ethnic mainstream vs. reception class for migrant and refugee students) plays a role in the associations, but due to lack of previous research, we do not pose hypotheses for the specific differences.

2 Method

2.1 Participants and procedure

This study was part of the RefugeesWellSchool project, a European Horizon 2020 study, dedicated to testing the effectiveness of school-based psychosocial interventions for increasing the wellbeing of migrant and refugee youth (RefugeesWellSchool, 2022). The research was conducted in six European countries: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In this study, we utilized data gathered from the participating teachers. The national ethical boards of participating countries, the Ghent University Ethical Board, Belgium (the coordinating institute), and the Horizon 2020 Ethical Review have approved the RefugeesWellSchool project.

The recruitment of schools took place between January 2018 and October 2019. Schools were informed about the RefugeesWellSchool project through municipal and national departments of education (Belgium, Denmark, Norway) or by contacting the schools directly (Finland, Sweden, UK), depending on the characteristics of the national education system (Spaas et al., 2021). The participating countries differ to some extent in the share of population with immigrant and refugee background (Belgium 17.3%, Denmark 12.4%, Finland 7.0%, Sweden 19.8%, Norway 15.7%, and United Kingdom 13.8%; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2020). However, the recruitment was conducted in all countries in similar manner, thus targeting especially those secondary schools that have a large share of migrant and refugee students. In all participating countries, the children with refugee and asylum seeker status have a right to education, and even the undocumented children have the same right. The schools’ participation was based on voluntariness. In total 83 schools (Belgium: n = 10; Denmark: n = 30; Finland: n = 16; Norway: n = 16; Sweden: n = 9; and United Kingdom: n = 2) enrolled in the study and provided data from teachers. The country-specific recruitment procedures can be found elsewhere (Durbeej et al., 2021; Kankaanpää et al., 2022; RefugeesWellSchool, 2022; Spaas et al., 2021).

Each country randomized the participating schools into intervention or waiting list control conditions. The RefugeesWellSchool project implemented five school-based psychosocial interventions that differed in their theoretical foundation, target group, elements, and tools. One intervention aimed to increase teachers’ multi-ethnic awareness and pedagogy, involving information and exercises on trauma, mental health, learning, and school-home cooperation (de Wal Pastoor, 2019). Three different interventions aimed at strengthening students’ social capital, cultural dialogue, or shared experiences in classrooms through participatory activities led by a teacher or a trained therapist (Rousseau et al., 2010; Tuk & de Neef, 2020; Watters et al., 2021). The fifth intervention was a cognitive-behavioral group treatment targeted at students suffering from posttraumatic symptoms (Smith et al., 1999).

A total of 460 teachers participated in the study. Of these, 433 provided data on the three main concepts and were thus included in the analyses. Table 1 presents the background characteristics of the sample. The teachers’ mean age was 43 years, but the Belgian teachers were on average younger than teachers in the other countries. In all countries except the United Kingdom, majority of teachers identified themselves as females. All participating teachers taught secondary school grades, a half teaching mainstream education with migrant students and students born in that country (hereafter termed “native students”) and another half teaching reception classes for newly arrived migrant and refugee students.

Data collection took place between January 2019 and September 2020. Researchers provided written information and consent forms to teachers who were willing to participate. They were informed that responses would be treated with confidentiality and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. Teachers answered the questionnaire in their countries’ national language, assessing their multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, work-related wellbeing, and background information in either paper (Belgium, Denmark, and United Kingdom) or electronic form (Finland, Norway, Sweden) using the LimeSurvey online tool (https://www.limesurvey.org/). The scales were validated in previous studies, but in case there was no previously validated translation of the questionnaire available, the translation with back-translation was conducted by each national research team. Due to the nature of the project, teachers were invited to answer the questionnaire at three time points across the intervention study. The response rate in the baseline was low and therefore teachers were invited to participate in the questionnaire until the third assessment. In this study, we used cross-sectional data with only one response per teacher due to low response rate in all time points. If data for baseline was lacking, the first response at the second or third time point was used. Data from both intervention and control conditions was included in this study.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Background information

Teachers answered questions on their age (years), gender (male/female/other), and class type, i.e., whether they taught a mainstream education class with migrant and native students or a reception class for migrant and refugee students. Further, researchers defined the intervention status of the school (1 = intervention; 2 = control) and time of assessment (1 = baseline, 2 = time point two, 3 = time point three).

2.2.2 Teacher multicultural attitudes

Teacher multicultural attitudes were measured using the 20-item Teacher Multicultural Attitudes Scale (TMAS) (Ponterotto et al., 1998). TMAS is a unidimensional scale comprising of 13 positively worded questions (e.g., “I find teaching a culturally diverse student group rewarding” and “Teaching methods need to be adapted to meet the needs of a culturally diverse student group”) and 7 negatively worded questions (e.g., “Today’s curriculum gives undue importance to multiculturalism and diversity” and “Being multiculturally aware is not relevant for the subject I teach.”). Teachers answered to which extent they agreed with the statements about their teaching on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale has been found reliable in the initial development study (α = 0.86) (Ponterotto et al., 1998) and in other studies (α = 0.82) (Cicchelli & Cho, 2007). The reliability in this study is reported in Sect. 2.4 Measurement Fit.

2.2.3 Teacher self-Efficacy

Teacher self-efficacy was measured using the short 12-item version of the Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). The TSES covers three subscales with dimensions touching on Efficacy for student engagement (e.g. “How much can you do to get students to believe they can do well in schoolwork?”), Efficacy for instructional strategies (e.g. “To what extent can you provide an alternative explanation or an example when students are confused?”), and Efficacy for classroom management (e.g. “How much can you do to control disruptive behavior in the classroom?”). Each subscale was measured with four items, each assessed using a 9-point scale anchoring at 1 (nothing), 3 (very little), 5 (some influence), 7 (quite a bit), and 9 (a great deal). The subscales of the 12-item scale have shown good reliabilities; engagement (α = 0.81), instruction (α = 0.86), management (α = 0.86), and the total scale (α = 0.90) (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). The TSES scale has also shown good construct and discriminant validities (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). The reliability in this study is reported in Sect. 2.4 Measurement Fit.

2.2.4 Teacher work exhaustion

Teachers’ experiences of burnout were measured with five items using the work exhaustion subscale of the Bergen Burnout Inventory (BBI) (Näätänen et al., 2003). The complete inventory has 15 items measuring three different dimensions: work exhaustion, cynicism toward work, and sense of inadequacy at work, with five items for each dimension. The exhaustion subscale includes statements such as “I often sleep poorly because of the situation at work” and “Even when I am off-work I often think about work-related affairs”. The teachers estimated how well the statements described their workload or current work situation using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). The exhaustion subscale (α = 0.86) has previously been found reliable in a Finnish sample of teachers (Malinen & Savolainen, 2016). The reliability in this study is reported in Sect. 2.4 Measurement Fit.

2.2.5 Teacher work dedication

Teachers’ work engagement was measured with five items of the dedication subscale of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) (Schaufeli et al., 2002). The complete UWES is a 17-item self-report covering subscales of vigor, dedication, and absorption. The dedication dimension includes statements such as “I find the work that I do full of meaning and purpose” and “I am enthusiastic about my job”. The teachers estimated how often the statement described their feelings about their work using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always) (original scale from 0 to 6). The reliability of the dedication subscale has been found to be good (α = 0.86) among a sample of Finnish teachers (Hakanen et al., 2006). The reliability in this study is reported in Sect. 2.4 Measurement Fit.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics 27 and all other analyses with MPLUS version 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). First, we investigated the construct validity of the multi-item measures for teachers’ multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, work exhaustion, and work dedication on the pooled data from all countries. We examined the measures’ descriptive statistics and group differences based on class type and conducted correlation analyses between the constructs and covariates. Second, with the tested measurement models, we analyzed the direct effects between teacher multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, and work-related wellbeing and the mediating role of self-efficacy in these paths using structural equation modeling (SEM). Teachers’ gender, age, intervention status and time point were added as covariates in the model based on theoretical and sample specific arguments. Third, we examined whether teachers’ experience of teaching either reception classes for migrant and refugee students or mainstream classes moderated these direct and mediated effects.

Before SEM analysis, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed on each latent construct to test the measurement models. The CFAs were estimated using robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation due to possible multivariate nonnormality. The CFAs were performed to test how well the theoretical models fitted our data. The model fits were assessed using the chi-square test statistic and p-value, and fit indices with the following criteria: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) value below 0.06 a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999) and below 0.08 an acceptable fit (Schreiber et al., 2006), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value below 0.08 an acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) values above 0.95 a good fit and above 0.90 an acceptable fit (Brown, 2015; Hu & Bentler, 1999). If the fit indices of the measurement models were non-acceptable, the modification indices were consulted for adjustment of the models. The models were adjusted either by adding residual covariances within a factor or by discarding items due to low factor loadings or high cross-loadings between factors. Only the theoretically sound adjustments were made one by one until a satisfactory model was reached. The reliability of the final measurement model scales was examined with Cronbach’s alphas and McDonald’s omegas. The factor loadings, standard deviations, significance levels, and residual variances of all items in the final measurement models are shown in Appendix.

To answer the research questions, structural equation models were fitted to the data using MLR estimation and the same fit indices and fit criteria as for the measurement models. We accounted for the hierarchical nature of our complex survey data, being nested in 83 different schools, by adding the school as cluster using the Type = complex command. In total, 2.2% of all measures were missing (Gender 1.8%, Age 3.2%, Class type 3.0%, TMAS 0.9%, TSES 2.7%, BBI 3.2% and UWES 4.7%). Missing data was considered in the analyses using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML).

2.4 Measurement fit

2.4.1 Teacher multicultural attitudes

The initial unidimensional 20-item Teacher Multicultural Attitude Survey (TMAS) showed poor model fit (χ2 = 559.05, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.69, TLI = 0.65, SRMR = 0.07). Due to the latent variable’s low coefficient of determination (R2) on items 5, 6, 7, and 8, these four items were discarded from future models. Ponterotto et al. (1998) have also suggested that the scale might be altered due to the inclusion of negatively worded questions. Due to the initial poor model fit and the potential negative wording effect, we fitted a model with a common factor and two wording factors within the common factor. All the remaining 16 items were set to load on the common factor. In addition, the six negatively worded items (3, 12, 15, 16, 19, 20) loaded on a negative wording factor, and the three positively worded items (1, 10, 11) loaded on a positive wording factor. The covariances between the negative wording factor and the common factor, and the positive wording factor and the common factor, were set to zero. In this way, the common factor was “cleaned” from the positive and negative wording effects. The modification indices further suggested adding residual covariance between items 3 and 16 (“Sometimes I think there is too much emphasis placed on multicultural awareness and training for teachers” and “Today’s curriculum gives undue importance to multiculturalism and diversity”, respectively), 4 and 13 (“Teachers have the responsibility to be aware of their students’ cultural backgrounds” and “In order to be an effective teacher, one needs to be aware of cultural differences present in the classroom”, respectively), and 17 and 18 (“I am aware of the diversity of cultural backgrounds in my classroom” and “Regardless of the racial and ethnic makeup of my class, it is important for all students to be aware of multicultural diversity”, respectively). These theoretically justified modifications were added to the model. This model then yielded acceptable fit (χ2 = 159.15, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.04). The scale was further used in the structural model as a one-item factor score instead of a latent construct with manifest variables due to sample size restrictions and the number of parameters. The reliability of the scale in this study was α = 0.79 and Ω = 0.69.

2.4.2 Teacher self-efficacy

The initial 12-item Teacher Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) with three-factor structure showed poor model fit (χ2 = 181.79, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.88, SRMR = 0.05). An inspection of the modification indices suggested that item 8 (“How well can you establish a classroom management system with each group of students?”) on factor Classroom management (TSES-CM) was problematic. It had a cross-loading on factor Instructional strategies (TSES-IS) and a residual covariance with another item within TSES-CM. Due to this, item 8 was discarded from future analyses. Further, modification indices suggested adding a residual covariance within TSES-CM between items 6 and 7 (“How much can you do to get children to follow classroom rules?” and “How much can you do to calm a student who is disruptive or noisy?”, respectively). The three factors showed strong correlations (r between .64 and .81, with p < .001). Due to high risk of multicollinearity between the factors in the structural model, we composed a second-order model with all three factors loading on one general TSES factor. The second-order structure does not affect the measurement model fit. The subscales loaded highly on the general TSES factor (λ = 0.98, 0.83 and 0.77 for TSES-SE, TSES-IS and TSES-CM, respectively). The second-order measurement model showed good fit (χ2 = 106.69, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.04). Again, due to sample size and number of parameters in the structural model, we formed a one-item factor score for the general TSES factor. In this study the reliability for the general TSES factor was (α = 0.86; Ω = 0.81) and for the subscales: Student engagement (TSES-SE; α = 0.77; Ω = 0.79), TSES-IS (α = 0.66; Ω = 0.66) and TSES-CM (α = 0.81; Ω = 0.89).

2.4.3 Work exhaustion

The 5-item work exhaustion subscale of the Bergen Burnout Inventory (BBI) showed initially moderate model fit (χ2 = 19.20, p = .002, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.03). The modification indices suggested allowing a residual correlation between items 3 and 5 (“Pressure related to work has caused difficulties in my private life (i.e., romantic relationship, family or friendship)” and “I constantly have a bad conscience because my work forces me to neglect my close friends and relatives”, respectively). After allowing for this theoretically plausible residual covariation, the model fit was excellent (χ2 = 5.14, p = 0.273, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, SRMR = 0.01). In the current study the reliability of the exhaustion subscale was α = 0.85 and Ω = 0.83.

2.4.4 Work dedication

The 5-item work dedication subscale of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) showed good model fit (χ2 = 10.38, p = .065, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.02). No further modifications of the scale were necessary. In the current study the reliability of the dedication subscale was α = 0.83 and Ω = 0.83.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of teachers’ multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, and work-related wellbeing in the entire data and according to the class type. In general, teachers showed high levels of positive multicultural attitudes and above average levels of self-efficacy. Teachers reported good work-related wellbeing, as they in general partly disagreed with statements on work exhaustion and showed high levels of work dedication. The teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students and teachers of mainstream education classes differed in their mean levels of multicultural attitudes and work exhaustion when using the Bonferroni corrected p value .0125 for these repeated comparisons. Teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students showed significantly more positive multicultural attitudes and less exhaustion compared to the mainstream education teachers. The general levels of self-efficacy and work dedication did not differ between teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students and teachers of mainstream education classes.

Table 3 presents the correlation analyses between the constructs (teachers’ multicultural attitudes, self-efficacy, and work-related wellbeing) and covariates (age, gender, intervention status, and measurement time point). The analyses show that gender was significantly correlated with teacher multicultural attitudes and work exhaustion with female teachers showing both more positive multicultural attitudes and more exhaustion. Gender was not correlated with either self-efficacy or work dedication (Table 3). Age, on the other hand, did not show significant correlations with any of the study constructs. The sample specific covariates intervention status and measurement timepoint suggested that the teachers in intervention group reported more positive multicultural attitudes but that these attitudes were more negative with time. The analyses also suggested a negative correlation between work dedication and time (Table 3).

3.2 Direct and mediated effects between multicultural attitudes and wellbeing

To test our first hypothesis suggesting that a high level of teachers’ multicultural attitudes is associated with lower level of work exhaustion and a higher level of work dedication, we fitted a model outlining the direct paths from teacher multicultural attitudes to work exhaustion and work dedication. The model fitted the data well (χ2 = 59.75, p = 0.029, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.04). Our first hypothesis was partially supported in that teacher positive multicultural attitudes were significantly associated with high level of work dedication (β = 0.30, p < .001). However, against our hypothesis, higher positive multicultural attitudes were not associated with lower work exhaustion (β = − 0.11, p = .189).

Our second hypothesis stated that teachers’ self-efficacy mediates the association between teachers’ multicultural attitudes and wellbeing at work. To test the hypothesis, we fitted a model with both the direct paths from multicultural attitudes to work exhaustion and work dedication, but also the mediating paths through self-efficacy. We used one-item factor scores for teacher multicultural attitudes and self-efficacy in the model to restrict the number of parameters related to the sample size. The model fitted the data well (χ2 = 66.06, p = .053, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.04). The mediated model is depicted in Fig. 2. The mediating hypothesis was supported, as highly positive multicultural attitudes were significantly associated with high level of self-efficacy (β = 0.32, p < .001), which was further associated with lower level of work exhaustion (β = − 0.17, p = .010) and higher work dedication (β = 0.40, p < .001). The regression coefficients for these indirect paths between multicultural attitudes and work exhaustion (β = − 0.05, p = .043) and multicultural attitudes and work dedication (β = 0.13, p < .001) were also statistically significant, confirming that self-efficacy mediated the association between multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing. The direct path from multicultural attitudes to work exhaustion turned out to be nonsignificant (β = − 0.06, p = .430) in the mediated model, suggesting that teacher self-efficacy completely mediated the association between positive multicultural attitudes and low work exhaustion (Zhao et al., 2010). However, the direct path from multicultural attitudes to work dedication remained significant (β = 0.18, p = .001) in the mediated model, thus suggesting only a complementary mediation (Zhao et al., 2010).

The mediated structural equation model for whole sample. Note. The SEM using factors scores of TMAS and TSES and Work exhaustion and Work dedication as latent constructs. Numbers depict standardized regression coefficients, correlations, residual variances, and their standard errors in parentheses. The statistically significant associations are shown in bold with *p < .05 and **p < .001. TMAS = Teacher multicultural attitudes; TSES = Teacher Self-Efficacy; Exhaustion = Work exhaustion; Dedication = Work dedication

We also added teachers’ age and gender as covariates in the mediated model, as they have been suggested to affect teachers’ wellbeing at work and showed significant correlations with some of the study variables (Table 3). We covaried age and gender in the model fitted with factor scores for TMAS and TSES factors but work exhaustion and dedication as latent factors. The model fitted the data well (χ2 = 97.03, p = .010, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.04). Gender had a significant association to work exhaustion (β = 0.16, p = .001), showing that female teachers reported more work exhaustion than male teachers. Gender was not associated with work dedication (β = 0.06, p = .208). Age was not associated to work exhaustion (β = 0.09, p = .121), nor to work dedication (β = − 0.002, p = .959).

We further verified whether due to our sample characteristics the intervention status or measurement time point affected the teachers’ work-related wellbeing outcomes, by adding them separately as covariates in the model with factor scores for TMAS and TSES but work exhaustion and dedication as latent factors. The model with intervention status as covariate fitted the data well (χ2 = 74.34, p = .073, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.04). Intervention status was not associated with either work exhaustion (β = 0.11, p = .139 or work dedication (β = –0.05, p = .342). The model with measurement time point as covariate fitted the data well (χ2 = 97.12, p = .001, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.04). Our study was conducted during the global Covid-19 pandemic, but we did not find an effect of time on teacher work-related wellbeing, as measurement time point was not significantly associated with either work exhaustion (β = 0.06, p = .405) or work dedication (β = − 0.08, p = .123).

3.3 Moderating role of class type

Our third research question explored the moderating role of class type, namely whether the hypothesized paths differed between teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students and teachers of multi-ethnic mainstream education. To examine this question, we fitted a multi-group model for the mediating effects of self-efficacy between teacher multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing. Due to the sample size per teacher group, we used factor scores for all measures. The model with only factor scores did not provide fit indices, as the degrees of freedom were zero.

The mediating hypothesis was partly supported in the group of teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students (Fig. 3), as positive multicultural attitudes were associated with higher self-efficacy (β = 0.27, p < .001), which further associated with higher work dedication (β = 0.27, p < .001), thus suggesting mediation. The regression coefficient for this indirect path was also statistically significant (β = 0.07, p = .001), confirming that self-efficacy mediated the association between multicultural attitudes and work dedication. However, also the direct path from multicultural attitudes to work dedication remained significant (β = 0.21, p = .013) in the mediated model, thus suggesting complementary mediation (Zhao et al., 2010). Teacher multicultural attitudes were not associated with work exhaustion (β = 0.02, p = .819), and self-efficacy did not mediate the association, as the indirect path was nonsignificant (β = − 0.02, p = .454).

The mediated structural equation model for teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students. Note. The SEM using factors scores for all scales. Numbers depict standardized regression coefficients, correlations, residual variances, and their standard errors in parentheses. The statistically significant associations are shown in bold with *p < .05 and **p < .001. TMAS = Teacher multicultural attitudes; TSES = Teacher Self-Efficacy; Exhaustion = Work exhaustion; Dedication = Work dedication

The mediating hypothesis was supported in the group of teachers of multi-ethnic mainstream education (Fig. 4). Multicultural attitudes were associated with higher self-efficacy (β = 0.36, p < .001), which was further associated with higher work dedication (β = 0.45, p < .001) and lower work exhaustion (β = − 0.22, p = .010), thus suggesting mediation. The regression coefficients for the indirect paths from multicultural attitudes to work dedication (β = 0.16, p < .001), and from multicultural attitudes to work exhaustion (β = − 0.08, p = .016) were statistically significant, confirming that self-efficacy mediated the paths from multicultural attitudes to work dedication and work exhaustion. The direct path from multicultural attitudes to work dedication was significant (β = 0.16, p = .025), suggesting complementary mediation (Zhao et al., 2010), but the direct path from multicultural attitudes to work exhaustion was nonsignificant (β = − 0.10, p = .256) in the mediated model, thus suggesting complete mediation of self-efficacy to work exhaustion (Zhao et al., 2010).

The mediated structural equation model for mainstream education teachers. Note. The SEM using factors scores for all scales. Numbers depict standardized regression coefficients, correlations, residual variances, and their standard errors in parentheses. The statistically significant associations are shown in bold with *p < .05 and **p < .001. TMAS = Teacher multicultural attitudes; TSES = Teacher Self-Efficacy; Exhaustion = Work exhaustion; Dedication = Work dedication

The type of teaching experience therefore seems to partly moderate the way multicultural attitudes are associated with work-related wellbeing. Among teachers of multi-ethnic mainstream education, self-efficacy mediated the effect of multicultural attitudes on work dedication but also on exhaustion, whereas among teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students, self-efficacy only mediated the effect of multicultural attitudes on work dedication. In teachers from both types of classes multicultural awareness had also a direct association with work dedication, indicating complementary mediation.

4 Discussion

Teachers have a central role in promoting the integration, wellbeing, and learning of migrant students. Accordingly, teacher characteristics, such as attitudes towards students’ cultural background, self-efficacy, and work-related wellbeing are considered important in improving student performance and wellbeing (Cherng & Davis, 2019; Darling-Hammond & Youngs, 2002; Herman et al., 2018; Zee & Koomen, 2016). The present study analyzed a sample of European teachers of multicultural classrooms to determine how their multicultural attitudes are associated with work-related wellbeing and whether self-efficacy explains this potential association. As hypothesized, the results reveal, first, that multicultural attitudes are important for teacher work-related wellbeing, as teachers with high levels of positive attitudes showed high work dedication. Second, high teacher self-efficacy mediated the association between positive multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing. Concerning the class type, results showed that the mediating role of self-efficacy between teacher multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing was different between teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students and teachers of multi-ethnic mainstream education. Our study thus highlights the importance of connections between teacher attitudes, self-efficacy, and wellbeing both generally and when teaching migrant students.

4.1 Multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing

Teachers’ positive multicultural attitudes were decisive for the positive aspects of teacher wellbeing but could not alleviate the negative aspects. In other words, positive multicultural attitudes were associated with high work dedication, but not with work exhaustion. Our results thus accord with previous studies that have found the multicultural approach to associate with high enthusiasm at work (Chwastek et al., 2021; Hachfeld et al., 2015). Teachers’ positive multicultural attitudes, in other words perceiving the teaching of migrant students as rewarding and understanding the importance of adapting teaching accordingly, seems to be strongly associated with high work dedication i.e., seeing one’s work as inspirational and meaningful.

The self-determination theory of competence, relatedness, and autonomy by Ryan and Deci (2000) may explain these positive associations: as teachers accumulate their knowledge and competence on multiculturality, they identify more with these values and accept them as personally important, leading to stronger motivation and engagement. Positive multicultural attitudes can also enhance the quality and understanding in teacher-student relationships, making encounters more affiliative, which in turn can increase dedication at work.

Our results differ from previous studies suggesting that teachers’ multicultural approach associates with lower levels of diversity-related burnout (Gutentag et al., 2018), whereas an assimilative approach contributes to higher levels of diversity-related burnout (Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003). Yet, in accordance with our results, Dubbeld et al. (2019) did not find an association between multiculturalism and burnout. At least three explanations can be found for multicultural attitudes not being able to decrease burnout in our study: First, multicultural teaching is demanding, especially when there is a shortage of school community level resources and support. Therefore, individual teacher’s positive multicultural attitudes may not be sufficient for decreasing burnout. In such cases, lack of support or acknowledgement and insufficient pedagogic and material resources form a risk for teacher burnout (Häggström et al., 2020; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Adequate support might include pedagogical training, multilingual teaching material and flexible school arrangements that are accommodated to diversity.

Second, other factors in the teacher’s work besides multiculturality may be more important in explaining burnout. Research suggests that work demands such as overload, ineffective leadership and high responsibilities are prominent in explaining the level of burnout (Bermejo-Toro et al., 2015). Third, different measurements used in studies may explain the different results. Previous studies have mostly utilized the concepts of multiculturalism versus assimilation and diversity-related burnout as their approach to study teacher burnout in multi-ethnic and multicultural classrooms (Dubbeld et al., 2019; Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003). These concepts are not equivalent to our choice of multicultural attitudes and work exhaustion and thus, their relationship might not be as straightforward.

4.2 Role of self-efficacy in multicultural attitudes and work-related wellbeing

In line with the hypothesis, our results show that teachers’ self-efficacy mediated the associations between positive multicultural attitudes and higher work-related wellbeing, indicated by both higher dedication and lower exhaustion. However, mediation was complete or necessary to explain work exhaustion, but only complementary to explain work dedication. In other words, teachers’ positive multicultural attitudes could alleviate work exhaustion only if they enhanced self-efficacy, involving practical improvements in student engagement and pedagogic management. Instead, positive multicultural attitudes could contribute to high work dedication both alone and with enhanced self-efficacy. We may thus argue that teachers’ attitudes can more strongly contribute to positive aspects of wellbeing, whereas more concrete improvements in pedagogic and support structures for teacher self-efficacy are needed to prevent burnout.

We are unaware of other studies testing the role of teachers’ self-efficacy between multicultural attitudes and wellbeing at work. Thus, we cannot directly compare our results to earlier literature. However, in accordance with our results, also previous research supports the positive links between multicultural approach and self-efficacy (Gutentag et al., 2018; Sela-Shayovitz & Finkelstein, 2020) and self-efficacy and work engagement (Li et al., 2017; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2014; Vera et al., 2012; Zee & Koomen, 2016). Positive multicultural attitudes may make teachers feel more capable of motivating their migrant students and using new teaching methods to meet their pedagogic and psychosocial needs. This increased self-efficacy can further relate both to experiences of mastery (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007) and more meaningful connectedness with the students. These could make teachers more dedicated to work, as feelings of competence and relatedness are core needs underlying human motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Earlier research has evidenced that teachers’ prejudiced or stereotypical attitudes can hamper their trust in migrant students’ learning capabilities and their own belief in their ability to motivate migrant students (Chwastek et al., 2021), whereas teachers’ positive multicultural attitudes function as opposite to these dynamics.

Our result of multicultural attitudes associating with lower levels of work exhaustion through self-efficacy supports previous studies showing that higher self-efficacy is associated with lower burnout (Egyed & Short, 2006; Schwarzer & Hallum, 2008; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2014; Zee & Koomen, 2016). Thus, although multicultural attitudes per se may not be able to reduce teacher work exhaustion, in combination with high self-efficacy it can be powerful enough to both increase the positive (dedication) and alleviate the negative (exhaustion) aspects of teacher wellbeing in multicultural classrooms. Self-efficacy, that is, the teacher’s belief in their own capability to induce positive student outcomes (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001) may thus potentiate an important cognitive shift that enables a teacher to better cope with the demands of multicultural education and school organization, thereby decreasing feelings of exhaustion (Bandura, 1977).

In our covariate analysis we found that teachers’ gender affected their levels of burnout with female teachers experiencing more work exhaustion. This gender difference is supported by some previous studies (Antoniou et al., 2006; Klassen & Chiu, 2010) and it is suggested to stem from female teachers’ higher tendency to overcommit to their job and have more problems in recovering (Kreuzfeld & Seibt, 2022). Our analyses further suggested that gender differences were not evident in levels of work dedication and that teachers’ age was not associated with wellbeing at work.

4.3 Class type modifying the associations between teacher characteristics

The experience of teaching either reception classes for migrant and refugee students or multi-ethnic mainstream classes was decisive especially in the way self-efficacy mediated the association between multicultural attitudes and wellbeing at work. The core mediating effect of self-efficacy between multicultural attitudes and work dedication was similar in both groups of teachers. Positive multicultural attitudes were associated with high self-efficacy, which in turn associated with higher work dedication. The results indicate, that regardless of the proportion of migrant students in the classroom, the recency of their migration, or the curriculum followed, teachers’ multicultural attitudes have the potential to increase their feeling of competence, and thereby their dedication at work. Positive multicultural attitudes were also directly linked to higher work dedication in both types of teachers, showing that the value of multiculturality for work dedication exists also without increases in self-efficacy. This speaks for universal training of cultural sensitivity among all teachers.

Differently, however, high self-efficacy could mediate between positive multicultural attitudes and low work exhaustion only in the mainstream education teachers, but not in teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students. The role of self-efficacy was thus more comprehensive among mainstream class teachers, including both the positive and negative aspects of wellbeing at work. Mainstream education teachers’ positive multicultural attitudes together with high self-efficacy may protect against work exhaustion by for example making teachers feel more competent in coping with the demands posed by cultural diversity in mainstream education. Multiculturally enhanced self-efficacy might be especially important for mainstream education teachers, as they may initially not be as well equipped to meet the needs of their migrant students from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Related to that, our results showed that in general mainstream education teachers had lower levels of positive multicultural attitudes than teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students, pointing to mainstream education teachers being less prepared to face the migrant students’ needs.

Interestingly, high self-efficacy did not mediate the effect of multicultural attitudes on work exhaustion among teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students. It could be that teaching this often very vulnerable group of students requires more pastoral care, exceeding the traditional role of a teacher. Therefore, for teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students, an increase in teaching self-efficacy is not enough to be able to cope with the demands brought by the migration experiences and difficult life situations of the students in these classes. Instead, teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students might need stronger support structures and a more extensive network of professionals to provide holistic care for their students and thus protect themselves from being overburdened by the demands on their roles as providers of both education and care. Further, in either of the teacher groups, multicultural attitudes did not associate directly with work exhaustion, suggesting that individual attitudes are not enough to safeguard teachers against work exhaustion. Rather, teachers of both reception classes for migrant and refugee students and mainstream education classes need collective support structures from the school to buffer against burnout.

In addition to the differing associations, results show that the two teacher groups differed also in their levels of work-related wellbeing. Mainstream education teachers reported more work exhaustion, which accords with previous studies suggesting that a lower proportion of ethnic minority students in classrooms might be associated with higher teacher burnout due to lack of experience and competence in addressing these students’ needs (Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003). However, we did not find sufficient support for the claim that a high proportion of ethnic minority students in the classroom would be associated with teachers’ higher work enthusiasm (Glock et al., 2019), as in our study mainstream education teachers and teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students showed similar levels of dedication to work. Yet, it should be noted that our result in differences in wellbeing may also relate to larger issues of school organization, such as different teaching conditions and resources, or the possibilities of engaging in professional development programs. Further, as the curricula between reception classes for migrant and refugee students and mainstream education classes differ, so do the goals that teachers are expected to achieve with their students. This might also affect the teachers’ experiences of exhaustion and dedication.

4.4 Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study can be appointed several strengths: for acknowledging both the positive and negative aspects of work-related wellbeing, and for explicitly testing the assumption of the mediating role of self-efficacy in the study of multicultural attitudes. We have conducted our analyses with rich data using validated measures among teachers from six different European countries.

However, our study also has limitations. Our sample might have suffered from selection biases, and we struggled to reach adequate response rate. Teachers who were interested or more experienced in multicultural issues may have been more likely to express their interest in participating in the study. Yet, due to sample-specific restrictions we were unable to test this possibility. The participating teachers also knew the overall aim of the RefugeesWellSchool project and might therefore have provided a more socially desirable response set than was the case. Due to insufficient sample size per country we had to analyze our data by combining teachers form all participating countries into one sample. Also, the division of class type was not similar between countries, as some countries (Belgium, Denmark, and Norway) had only teachers of reception classes for migrant and refugee students participating in the study. These two sample-related restrictions may point to the possibility of country effects on the models, as unfortunately, we were unable to test the measurement invariance across the countries due to the restricted sample size per country. We, however, accounted for the hierarchical nature of our data by using multilevel modeling and schools as clusters. Our restricted sample size also precluded us from entering all the study constructs as latent variables in the models, thus making us unable to account for the measurement error of those constructs. In general, our study with the restricted number of teachers within each country serves as the initial description of the effects of multicultural attitudes on self-efficacy and wellbeing at work and offers a starting point for more specific country-wise comparison in future. These sample-related limitations warrant caution when generalizing the results to teachers of migrant students in general.

Further, our endogenous variables had large residuals, meaning that much of the variation in the measures had been left unexplained by our models. In future studies, it would thus be recommended to explore which other important factors could be included in the models as predictors. For example, several issues related to teacher education, school organization and teachers’ work conditions might provide useful insight if added to these models. The invariance of our measures could also be affected by the fact that although we used validated scales, we had to use some unvalidated translations of our scales, as validated translations were not available in all languages.

Our study used data cross-sectionally, so we cannot make conclusions about the causality of the relationships that we have modeled. This highlights the need to use longitudinal data to consolidate the direction of the causal pathways in further studies. However, our statistical models assume causal paths that we have built based on previous research. Also, our study, as most other studies, used solely teacher data to analyze these concepts. Yet, it would be very fruitful in further studies to also include measures of student wellbeing in multi-ethnic classrooms, as this would further inform us on how exactly these teacher characteristics might be beneficial to an ethnically diverse student body.

5 Conclusion

This study among teachers in multi-ethnic classrooms in six European countries showed that teachers’ multicultural attitudes are important for their work-related wellbeing. Positive attitudes contributed to teachers’ self-efficacy, involving competence and pedagogic mastery, which further enhanced wellbeing. The findings are important, because the number of migrant students in schools is growing, demanding novel attitudinal and professional competencies.

Yet, many teachers feel that their multicultural education training is inadequate and does not give them actual pedagogical tools to be used in the classroom (Bottiani et al., 2018; Parkhouse et al., 2019; Szelei et al., 2020). Our results indicate that teachers’ professional development training should include both knowledge about multiculturalism and specific training elements on how to increase feelings of efficacy in engaging migrant students in the classroom and creatively adapting teaching methods to better meet the needs of ethnically and culturally diverse classes. In light of these results, schools should review and strengthen their support structures for multicultural education in order for teachers to be able to provide culturally competent teaching.

Finally, from a single teacher’s point of view, it may feel overwhelming to tackle the personal or professional insecurities related to cultural diversity in the midst of lacking resources, education, or support. Instead, teachers should be reminded that a good starting point for culturally aware teaching is meeting their students from different cultures with respect and open mind, without imposing cultural or ethnic stereotypes. For self-efficacy, apart from worrying what went wrong, teachers should also be encouraged to acknowledge and feel proud about the things in which they succeeded. We believe such behaviors can lead towards the development of increasingly supportive and competent schools also for ethnic minority and migrant students.

References

Abacioglu, C. S., Volman, M., & Fischer, A. H. (2019). Teacher interventions to student misbehaviors: The role of ethnicity, emotional intelligence, and multicultural attitudes. Current Psychology, 40(12), 5934–5946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00498-1

Abacioglu, C. S., Volman, M., & Fischer, A. (2020). Teachers’ multicultural attitudes and perspective taking abilities as factors in culturally responsive teaching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 736–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12328

Acquah, E. O., Alisaari, J., & Commins, N. L. (2019). Finnish teachers’ perspectives about linguistic and cultural diversity. In S. Hammer, K. Mitchell Viesca, & N. L. Commins (Eds.), Teaching content and language in the multilingual classroom: International research on policy, perspectives, preparation and practice (pp. 54–75). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429459443-6

Amitai, A., Vervaet, R., & Van Houtte, M. (2020). When teachers experience burnout: Does a multi-ethnic student population put out or spark teachers’ fire? Pedagogische Studien, 97(2), 125–145.

Antoniou, A. S., Polychroni, F., & Vlachakis, A. N. (2006). Gender and age differences in occupational stress and professional burnout between primary and high-school teachers in Greece. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 682–690. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610690213

Bakker, A. B., & Bal, P. M. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X402596

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476

Bandura, A. (1977). Self efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75361-4

Bates, L. A., & Glick, J. E. (2013). Does it matter if teachers and schools match the student? Racial and ethnic disparities in problem behaviors. Social Science Research, 42(5), 1180–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.04.005

Bermejo-Toro, L., Prieto-Ursúa, M., & Hernández, V. (2015). Towards a model of teacher well-being: Personal and job resources involved in teacher burnout and engagement. Educational Psychology, 36(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1005006

Bottiani, J. H., Larson, K. E., Debnam, K. J., Bischoff, C. M., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2018). Promoting educators’ use of culturally responsive practices: A systematic review of inservice interventions. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(4), 367–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117722553

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press.

Brunsting, N. C., Sreckovic, M. A., & Lane, K. L. (2014). Special education teacher burnout: A synthesis of research from 1979 to 2013. Education and Treatment of Children, 37(4), 681–711. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2014.0032

Celeste, L., Baysu, G., Phalet, K., Meeussen, L., & Kende, J. (2019). Can school diversity policies reduce belonging and achievement gaps between minority and majority youth? Multiculturalism, colorblindness, and assimilationism assessed. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(11), 1603–1618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219838577

Cherng, H.-Y.S., & Davis, L. A. (2019). Multicultural matters: An investigation of key assumptions of multicultural education reform in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117742884

Choi, S., & Lee, S. W. (2020). Enhancing teacher self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms and school climate: The role of professional development in multicultural education in the United States and South Korea. AERA Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858420973574

Choi, S., & Mao, X. (2021). Teacher autonomy for improving teacher self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms: A cross-national study of professional development in multicultural education. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101711

Chwastek, S., Leyendecker, B., Heithausen, A., BalleroReque, C., & Busch, J. (2021). Pre-school teachers’ stereotypes and self-efficacy are linked to perceptions of behavior problems in newly arrived refugee children. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 574412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.574412

Cicchelli, T., & Cho, S.-J. (2007). Teacher multicultural attitudes: Intern/teaching fellows in New York City. Education and Urban Society, 39, 370–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124506298061

Darling-Hammond, L., & Youngs, P. (2002). Defining “highly qualified teachers”: What does “scientifically-based research” actually tell us? Educational Researcher, 31(9), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X031009013

de Boer, H., Bosker, R. J., & van der Werf, M. P. C. (2010). Sustainability of teacher expectation bias effects on long-term student performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(1), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017289

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 27(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Dubbeld, A., de Hoog, N., den Brok, P., & de Laat, M. (2019). Teachers’ attitudes toward multiculturalism in relation to general and diversity-related burnout. European Education, 51(1), 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2017.1401435

Durbeej, N., McDiarmid, S., Sarkadi, A., Feldman, I., Punamäki, R. L., Kankaanpää, R., Andersen, A., Hilden, P. K., Verelst, A., Derluyn, I., & Osman, F. (2021). Evaluation of a school-based intervention to promote mental health of refugee youth in Sweden (The RefugeesWellSchool trial): Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials, 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13063-020-04995-8/FIGURES/2

Egyed, C. J., & Short, R. J. (2006). Teacher self-efficacy, burnout, experience and decision to refer a disruptive student. School Psychology International, 27(4), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306070432

Geerlings, J., Thijs, J., & Verkuyten, M. (2018). Teaching in ethnically diverse classrooms: Examining individual differences in teacher self-efficacy. Journal of School Psychology, 67, 134–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.12.001

Glock, S., Kovacs, C., & Pit-ten Cate, I. (2019). Teachers’ attitudes towards ethnic minority students: Effects of schools’ cultural diversity. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 616–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/BJEP.12248

Glock, S., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Klapproth, F., & Böhmer, M. (2013). Beyond judgment bias: How students’ ethnicity and academic profile consistency influence teachers’ tracking judgments. Social Psychology of Education, 16(4), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-013-9227-5

González-Romá, V., Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Lloret, S. (2006). Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.01.003

Granziera, H., & Perera, H. N. (2019). Relations among teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, engagement, and work satisfaction: A social cognitive view. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.02.003

Gutentag, T., Horenczyk, G., & Tatar, M. (2018). Teachers’ approaches toward cultural diversity predict diversity-related burnout and self-efficacy. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(4), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117714244

Hachfeld, A., Hahn, A., Schroeder, S., Anders, Y., & Kunter, M. (2015). Should teachers be colorblind? How multicultural and egalitarian beliefs differentially relate to aspects of teachers’ professional competence for teaching in diverse classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 48, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.02.001

Häggström, F., Borsch, A. S., & Skovdal, M. (2020). Caring alone: The boundaries of teachers’ ethics of care for newly arrived immigrant and refugee learners in Denmark. Children and Youth Services Review, 117, 105248. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2020.105248

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Herman, K. C., Hickmon-Rosa, J., & Reinke, W. M. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717732066

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Structural equation modeling: A multidisciplinary journal cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hultell, D., & Gustavsson, J. P. (2011). Factors affecting burnout and work engagement in teachers when entering employment. Work, 40(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2011-1209

Kankaanpää, R., Aalto, S., Vänskä, M., Lepistö, R., Punamäki, R.-L., Soye, E., Watters, C., Andersen, A., Hilden, P. K., Derluyn, I., Verelst, A., & Peltonen, K. (2022). Effectiveness of psychosocial school interventions in Finnish schools for refugee and immigrant children, “Refugees Well School” in Finland (RWS-FI): A protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials, 23(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13063-021-05715-6

Kien, C., Sommer, I., Faustmann, A., Gibson, L., Schneider, M., Krczal, E., Jank, R., Klerings, I., Szelag, M., Kerschner, B., Brattström, P., & Gartlehner, G. (2019). Prevalence of mental disorders in young refugees and asylum seekers in European Countries: A systematic review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(10), 1295–1310. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00787-018-1215-Z/FIGURES/2

Klassen, R. M., Aldhafri, S., Mansfield, C. F., Purwanto, E., Siu, A. F. Y., Wong, M. W., & Woods-McConney, A. (2012). Teachers’ engagement at work: An international validation study. The Journal of Experimental Education, 80(4), 317–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2012.678409

Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019237

Klusmann, U., Aldrup, K., Roloff, J., Lüdtke, O., & Hamre, B. K. (2022). Does instructional quality mediate the link between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and student outcomes? A large-scale study using teacher and student reports. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(6), 1442–1460. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000703.supp

Klusmann, U., Richter, D., & Ludtke, O. (2016). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion is negatively related to students’ achievement: Evidence from a large-scale assessment study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(8), 1193–1203. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000125

Kreuzfeld, S., & Seibt, R. (2022). Gender-specific aspects of teachers regarding working behavior and early retirement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 829333. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.829333

Li, M., Wang, Z., Gao, J., & You, X. (2017). Proactive personality and job satisfaction: The mediating effects of self-efficacy and work engagement in teachers. Current Psychology, 36(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9383-1