Abstract

Academic engagement has been shown to deteriorate in lower secondary school, and it is necessary to find ways to prevent this so that students’ engagement and achievements do not decline irrevocably. Teacher support for growth mindset (TSGM) is likely to influence students’ mindsets while also promoting academic engagement and achievement. This cross-sectional study first examined the extent to which lower secondary school students (N = 1608) perceived their teachers’ classroom pedagogy as supportive of their growth mindset and students’ growth mindset beliefs. The study’s main purpose was to test a latent structural equation model specifying that perceived TSGM is directly related to students’ growth mindset, directly and indirectly related to academic engagement (behavioral and emotional), and indirectly related to academic achievement. Students’ perceived growth mindset and academic engagement thus served as intermediate variables. The results verified that TSGM was indeed related to growth mindset and academic engagement, the latter both directly and via students’ perceived growth mindset. Furthermore, TSGM was also related to academic achievement via students’ growth mindset and academic engagement. The results suggest that TSGM can facilitate students’ growth mindset and academic engagement and, thereby, achievement in lower secondary school, a period during which students may struggle with academic motivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Academic motivation and engagement are vital for students’ learning and achievement (Dweck & Yeager, 2019; Eccles & Roeser, 2009; Wang et al., 2019). Motivation to complete schoolwork has been shown to be important for the student’s current and future learning experiences (Steiger et al., 2014). However, during adolescence, students are typically less motivated and engaged in academic work than their younger counterparts (Bostwick et al., 2020). Students’ academic engagement exhibits a downward tendency from primary to lower secondary school (Wang et al., 2015). Contextual, behavioral, and emotional factors may impact students’ academic motivation at this time (Eccles & Roeser, 2009). In the Norwegian educational framework, deterioration in academic engagement is likely to be exacerbated by the introduction of grades in lower secondary school, which fosters a more competitive environment that may cause some students to become pessimistic with respect to their academic goals (Bakken, 2022).

Students who have a growth mindset see intelligence as malleable through effort and persistence with challenging learning tasks (Dweck, 2007). By contrast, students whose mindset is fixed tend to believe that intelligence is innate and unchangeable (Dweck, 2007). Mindsets or beliefs about intelligence have been regarded as a relatively stable individual characteristic (Blackwell et al., 2007; Dweck, 2007; Yeager et al., 2019). Yet, findings suggest that fixed mindset could be reduced, and growth mindset enhanced. Dweck and Yeager (2020) and Tipton et al. (2023) claim that a growth-oriented mindset is empirically shown to have the potential to affect or nurture students’ engagement and achievement in school. Yet, there is an ongoing debate as to whether growth mindset affects academic achievement (e.g., Macnamara & Burgoyne, 2022). Findings concerning the effect of growth mindset on academic achievement show some inconsistency. Two meta-analyses by Sisk et al. (2018) showed inconsistent findings. Yet, a more recent meta-analysis (Burnette et al., 2023) showed a moderate positive effect on academic achievement of interventions to promote a growth mindset. Most existing studies have focused on individually oriented interventions aimed at stimulating students’ growth mindset (Yeager et al., 2019). Interventions are often also of very short duration. The types of interventions used may not have been able to change the educational context in a growth mindset-supportive direction. This may help explain the inconsistency of the findings. These results suggest that more attention probably needs to be directed toward the role that classroom pedagogy and teachers’ practice could play in facilitating students’ growth mindset. Past research has largely focused on perceptions of teachers' mindsets (Hecht et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2022). The present work provides a novel addition to this body of work by examining how a perceived contextual factor—namely, students’ perceptions of teacher support for growth mindset (TSGM)—is associated with students’ growth mindset, engagement, and academic achievement in lower secondary school.

1.1 Teachers’ support for students’ growth mindset and students’ growth mindset

Classroom pedagogical practice that endorses students’ growth mindset has been shown to entail process-oriented and individually adapted learning possibilities (Cai et al., 2023). Moreover, approaches that encourage students to pursue challenging learning activities, inspire the use of various learning strategies, and convey that failure provides learning opportunities as well as promoting the idea that the brain can be trained like a muscle are likely to nudge students’ mindsets in a more growth-oriented direction (Rissanen et al., 2019, 2021).

While the existing empirical research regarding the characteristics of a pedagogy that supports a growth mindset is relatively modest, several studies have addressed this issue. For example, classroom observations and teachers’ reports indicate that teachers who exhibit various behaviors promoting the belief that intelligence is incremental do indeed influence students’ growth mindset (Schmidt et al., 2015). Likewise, interventions that promote a learning environment that is conducive to an adaptive perspective regarding students’ mindsets highlight the importance of teachers’ pedagogical approach with respect to students’ mindsets and engagement (Hecht et al., 2021).

Engagement in challenging tasks is believed to be crucial for enhancing brain capacity and is emphasized as an important aspect of growth mindset pedagogy (Rissanen et al., 2021). While attempting challenging tasks is associated with a high risk of failure, failures typically offer valuable learning opportunities, and helping students to recognize this will likely be integral to a pedagogy designed to cultivate a growth mindset. (Rege et al., 2020). Coping with failures is easier in a mastery climate in which teachers’ pedagogical practice emphasizes the learning process and individual improvements in learning and understanding rather than comparison with others (Meece et al., 2006). Support for a mastery orientation is thus regarded as central to growth mindset pedagogy (Mesler et al., 2021). Navigating failure entails trying different approaches or strategies to understand or complete the task. Encouraging the use of different approaches or strategies in the learning process is thus likely to be integral to TSGM (Patterson et al., 2016). However, this requires time, effort, and perseverance on the students’ part, and, accordingly, support for this will be crucial. In demanding learning processes, students may encounter obstacles that they struggle to overcome independently. The encouragement of help-seeking behavior and the provision of assistance in overcoming such barriers are also believed to be key to sustaining a demanding learning process inspired by a growth mindset (Yeager et al., 2022).

1.2 Students’ growth mindset and its links to academic engagement and achievement

Students with a growth-oriented mindset are believed to be more engaged and achieve higher scores (Claro et al., 2016; Dweck & Yeager, 2020). Previous studies have indicated that growth mindset can be stimulated over shorter periods of time (e.g., Niiya et al., 2004), and that it can be cultivated on a more permanent basis by interventions that support its relationship to behavioral and emotional aspects of engagement and academic achievement (Lin-Siegler et al., 2016). Students who endorse a growth mindset have also been shown to seek more challenging and advanced academic assignments (Rege et al., 2020). Challenge-seeking is thought to be an important precursor to motivational learning processes, possibly mediated by increased perceived competence in completing challenging assignments (Dweck & Yeager, 2019). Students’ growth mindset is thus likely to play a role in behavioral engagement, as shown by effort and persistence in schoolwork (Honicke & Broadbent, 2016). Growth mindset is also believed to enhance engagement in deep, self-driven, and valued learning processes, which are likely to reflect an interest in the topic through emotional engagement (Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Yeager & Dweck, 2012). Higher perceived academic competence is also associated with enhanced awareness of the relevance of schoolwork (Burnette et al., 2023), which, in turn, bolsters students’ academic achievements (Wu, 2019).

1.3 Teachers’ support for students’ growth mindset and student academic engagement

TSGM in the classroom may be of considerable importance for both students’ mindsets and engagement (e.g., Rissanen et al., 2021), as the encouragement from the teacher of academic persistence may fuel beliefs and a sense of effort in learning activities and bolster active class participation as well as making the students more willing to ask for help, when necessary, thus creating a context that makes learning enjoyable and interesting in addition to stimulating students’ beliefs that their abilities are malleable (Ronkainen et al., 2019; Sahagun et al., 2021). Building on this, TSGM likely plays a key role in nurturing students’ mindsets and academic engagement, thereby indirectly influencing their academic achievement. Given that TSGM facilitates a relatively broad spectrum of motivational aspects, it may also affect students’ academic engagement without inspiring their growth mindset. For example, TSGM may encourage students to invest greater effort, thereby influencing their behavioral engagement in learning activities, and this may happen without necessarily affecting students’ growth mindset (beliefs that abilities can be developed). Moreover, given that teachers who implement growth mindset pedagogy often also emphasize the value of learning for its own sake, they may foster students’ interest and emotional engagement in learning processes (Ronkainen et al., 2019), creating a direct link without affecting their growth mindset (Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Dweck & Yeager, 2019).

1.4 Academic engagement and achievement

Academic achievements encompass multiple learning domains, measures of performance outcomes, and cognitive goals across different subjects (Steinmayr et al., 2014). Achievement is therefore acknowledged as a multifaceted construct that encompasses various educational outcomes that configure acquired knowledge in terms of grade point average (GPA; Steinmayr et al., 2012). Academic engagement is known to play a central role in achievement, as engaged students tend to enjoy greater success in school by virtue of their interest in learning and the effort that they invest in it (Lei et al., 2018; Wang & Holcombe, 2010). In the present study, academic engagement is regarded as a multifaceted construct that includes behavioral and emotional aspects (Fredricks et al., 2004). Engagement is thus promoted by a motivated attitude, which enhances the quality of a student’s involvement in their academic activities, goals, and values (Skinner et al., 2009). Accordingly, behavioral engagement is characterized by students who are engaged in learning activities, who are focused, and who actively participate in the environment that surrounds learning. Emotional engagement concerns students’ interest, purpose, and values in learning and their schoolwork (Skinner et al., 2009). Academic engagement thus aligns with aspects of self-determination theory in the educational context (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009), whereby behavioral engagement is operationalized by students’ motivated behavior, whereas emotional engagement includes their autonomous motivation with respect to their schoolwork (Skinner et al., 2009). Academic engagement is therefore linked to motivation and higher achievement, school completion (Froiland & Worrell, 2016), and richer future career prospects (Mesler et al., 2021).

Although underlying assumptions regarding the mechanisms that govern students’ academic engagement and achievement are based on the notion that engagement leads to success by means of increased learning activity (the virtuous circle of learning; Wäschle et al., 2014), behavioral engagement, which may be understood as the behavioral manifestation of growth mindset, has a more obvious link to achievement than emotional engagement (Lei et al., 2018). Emotional engagement, meanwhile, entails emotional activation (Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2012), and while positive academic emotional experiences may engender optimism and joy, negative emotions—such as frustration or even boredom—may also arise (Pekrun, 2016). The more challenging learning assignments that are implemented at lower secondary school level may activate negative emotions, which, in turn, are likely to diminish students’ emotional engagement and interest (Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2012). Based on these assumptions, the two aspects of engagement may differ with respect to how they relate to students’ academic achievement (Furrer & Skinner, 2003).

1.5 The present study

The frequency of students’ perceived TSGM and the extent to which they have a growth mindset reflect the sample variation and have the potential to contribute descriptive information concerning the extent to which students value these aspects of classroom pedagogical practice in an educational context. Moreover, TSGM that espouses the principles of a growth mindset pedagogy is expected to substantiate students’ perceived growth mindset, and, in the present study, it is expected to emerge as a relationship between the measure of perceived TSGM and indirect relationships with academic engagement and achievement. However, it is difficult to identify any TSGM behavior that does not include a relatively wide spectrum of teacher actions that are supportive of academic engagement without affecting students’ beliefs that their intelligence is incremental, which is how growth mindset is defined and measured in this study. Thus, the measurement of perceived TSGM is also expected to be directly associated with measures of academic engagement.

Based on the above, the study posed the following four research questions and the associated hypotheses (H):

-

RQ1 What are adolescent students’ levels of perceived TSGM and their own perceived growth mindset?

-

RQ2 To what degree is TSGM associated with students’ growth mindset? TSGM is expected to be directly and positively associated with students’ perceived growth mindset (H2a).

-

RQ3 To what extent is TSGM directly and indirectly related to students’ academic engagement (emotional and behavioral)? Based on the presented growth mindset pedagogy, TSGM is expected to be directly and positively associated with students’ perceived behavioral and emotional academic engagement (H3a) but is also expected to be indirectly related to academic engagement via students’ growth mindset (H3b).

-

RQ4 How is TSGM related to academic achievement? Although this has not been investigated extensively, TSGM and academic engagement are not expected to be directly related but rather to be indirectly associated with academic achievement via students’ growth mindset (H4a). We further assume a serial intermediate association between TSGM and academic achievement via students’ growth mindset and behavioral and emotional engagement: we expect that behavioral engagement will exert a more obvious link to achievement, whereas our expectation regarding emotional engagement is less certain, based on previous research results (e.g., Lei et al., 2018; H4b).

2 Method

2.1 Sample and procedure

This study is part of a larger research project entitled Resilient. The project follows the ethical standards for good practice established by the Norwegian Data Protection Authority and was approved in 2020 by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data.

The cross-sectional sample in this study comprised students from 87 classes in 25 lower secondary schools across three small- to middle-sized municipalities in southwest Norway. In total, 2146 eighth-grade students (corresponding to the first year of lower secondary school) were invited to participate in the project. Of these, 1968 (91.7%) agreed to participate. Parents or guardians signed consent letters on their behalf due to the students’ young age at the time (ranging from 13 to 14 years).

In total, N = 1608 (74.9%) of the students completed the first survey assessment in March 2021 (50.4% males). The survey was digitally distributed for one school hour, with the main teacher present in the classroom.

2.2 Measurements

The study measures are presented below, and the item wording, factor loadings, and measurement model fit are all presented in the “Appendix”. The assessments for almost all variables in this study were identical and had a six-step scoring format (from 1 to 6): Strongly disagree, disagree, disagree a little, agree a little, agree, strongly agree. Unless stated otherwise in this section, this six-step format was used. Given that the initial analysis adopted a confirmatory factor analytic (CFA) approach, scale reliability is provided in terms of McDonald’s omega (ω) as well as in Cronbach’s alpha (α).

2.2.1 Academic achievement

Students’ academic achievement was used as a dependent variable. To assess academic achievement, GPA in math, English, natural sciences, Norwegian, and social sciences from the end of eighth grade in spring 2021 was used to create a latent variable that represented academic achievement. Reliability for the measure given in Cronbach’s alpha was good (α = 0.89), and equal values were found for McDonald’s omega (ω = 0.89).

2.2.2 Academic engagement (emotional and behavioral engagement)

Students’ academic engagement was assessed using a modified version of Skinner et al.’s (2009) two behavioral and emotional engagement scales. These measures are based on self-determination theory (SDT), and the modified versions of the scales have been documented by Eriksen and Bru (2023). Behavioral engagement concerns the effort that students invest in their schoolwork and included seven items (α = 0.93 and ω = 0.92) (e.g., “I have tried hard to do well in school”). Emotional engagement (α = 0.96 and ω = 0.96) included six items assessing students’ interest and enjoyment with respect to their academic work (e.g., “The subjects we have had at school have interested me”).

2.2.3 Growth mindset

The Self-efficacy Formative Questionnaire (SEFQ) and items forming the component of beliefs that abilities grow with effort (Gaumer Erickson et al., 2016) were used to assess how students perceive their ability to undertake academic work with a growth-oriented mindset (e.g., “I believe that the brain can be developed like a muscle” and “My ability grows with effort”). The scale’s reliability was high (α = 0.92 and ω = 0.92). The measurement model of growth mindset yielded acceptable fit to the data (RMSEA; 0.08, CFI; 0.98, TLI; 0.95, and SRMR; 0.02). For more detailed information, please see the “Appendix”.

2.2.4 Teachers’ support for growth mindset

A seven-item scale was developed for the Resilient project to assess students’ perceptions regarding the extent to which their teachers promote a growth mindset pedagogy in the learning environment—for example, encouraging students to seek new learning challenges, promoting a mastery climate, stimulating incremental beliefs, and helping students overcome academic barriers (e.g., “The teachers have said that making mistakes provides me with an opportunity to learn” and “The teachers have been concerned that I focus on my development and not on comparing myself to others”). The scale’s reliability was relatively high (α = 0.87 and ω = 0.89). The measurement model fit was acceptable (RMSEA; 0.07, CFI; 0.96, TLI; 0.94, and SRMR; 0.02). More detailed information about the model fit may be found in the “Appendix”.

The results of the overall measurement model based on CFA and including all variables yielded a good fit to the data: χ2 = 1583.64 (395), RMSEA; 0.04 (90% CI, 0.04–0.05), CFI; 0.96, TLI; 0.95, SRMR; 0.03. Information regarding the fit for all measurement models for each separate latent variable may be found in the “Appendix”.

2.2.5 Controlling for parents’ educational level and gender

Parents’ educational level has previously been shown to be correlated with students’ academic achievements (Roksa & Potter, 2011). Moreover, research suggests that parents with higher educational degrees have higher academic expectations of their children (Steinmayr et al., 2012). High parental expectations and aspirations may also influence students in terms of the effort and interest they invest in their schoolwork (Régner et al., 2009). In support of this notion, research has shown that highly educated parents typically encourage their children to regard failure as a component of learning and as a process through which abilities can be developed (Haimovitz & Dweck, 2017), thus bolstering their child’s growth mindset.

Previous studies investigating gender differences in engagement and achievement among students suggest that adolescent females are more academically engaged, persistent (Wang & Holcombe, 2010), and successful in school than their male counterparts (Markussen et al., 2011). Moreover, female students tend to be more organized and better able to structure their time with respect to their schoolwork (Bru et al., 2021). Meanwhile, adolescent male students are more likely to have a growth-oriented mindset than their female counterparts (Dweck, 2007). However, these findings are somewhat inconsistent, and other studies have detected no gender-based differences in growth mindset among adolescent students (Macnamara & Rupani, 2017), rendering current expectations regarding gender influences on students’ perceived growth mindset somewhat unclear.

Based on previous findings, parents’ educational level and gender were used as covariates, controlling for students’ perceived growth mindset, academic engagement, and achievements in school. Parents’ educational level was based on register data obtained from Statistics of Norway (2023). Categories ranging from 1 to 8 indicated level of education. Categories 1–3 were merged into a single category given that the variation was minor: “No education and preschool education” (1); “Primary education” (2); and “Lower secondary education” (3). The remaining categories represent “Upper secondary, final year” (4); “post-secondary non-tertiary education” (5); “First stage of tertiary education, undergraduate level” (6); “First stage of tertiary education, graduate level” (7); and “Second stage of tertiary education (postgraduate education)” (8). The average mean educational level and standard deviation for mothers was M = 5.10 (SD = 1.34); for fathers, the mean value for education level was somewhat lower: M = 4.83 (SD = 1.40).

Gender was measured using a dichotomous variable in which males were given the value 0 and females the value 1.

2.3 Analytic strategy

This study employs a latent structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. First, all data were investigated using descriptive statistics. Composite scores for the independent study variables TSGM and students’ growth mindset were obtained by computing means across items in the two scales. Moreover, to illustrate the variation in these scores, composite scores were divided into six equal intervals resembling the scoring format of single items. These scores are referred to as the categorized mean scores. The mean, standard deviation, and bivariate correlations for all study variables are also reported. Second, study variables were estimated separately as latent constructs using CFA to establish discriminant and convergent validity (see the results in the “Appendix”). Third, an overall measurement model with all latent variables was subsequently estimated to ensure that each construct loaded on its intended factor. Mplus version 8.9 was used for the analysis. The following criteria were used to assess good fit to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1998): standardized root-mean-squared residual (SRMR) > 0.08, accompanied by the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) (Tucker & Lewis, 1973) and the comparative fit index (CFI), with cut-off values close to 0.95. The root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) was calculated with a cut-off value of 0.06 or less, indicating a good fit, and 0.08, indicating an acceptable model fit, supplemented by a 90% confidence interval (CI). For the structural modeling, students’ academic achievements were used as the dependent variable, TSGM was treated as the independent variable, and students’ perceived growth mindset beliefs as well as two constructs of academic engagement (behavioral and emotional) were treated as serial intermediate variables combined with a random resampling to estimate the distribution by the bias-corrected bootstrap procedure at the 95% confidence interval (CI) (MacKinnon et al., 2004). Given the non-normal distribution of some variables, parameters were estimated using a robust maximum likelihood estimator (Chou & Bentler, 1995). An examination of intraclass correlations (ICC) was necessitated, as the students were nested within classes. The ICC results were generally low and indicated a low classroom-level dependency of observations (0.01–0.04). Design effects for study variables ranged between 1.02 and 1.76, eliminating the need to use multilevel analysis (Asparouhov et al., 2006). Nonetheless, a type complex was included to adjust the standard errors in estimation.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 provides the mean and standard deviations for the composite scores of the study variables. Regarding the first research question, the frequencies for categorized mean scores are also given, and the results indicate that perceived TSGM and students’ growth mindset had relatively high mean scores. Frequencies for the categorized mean scores indicated that about 90% agreed (“slightly” through “completely”) with the statements assessing these concepts. Approximately 70% used one of the two most positive response alternatives (“quite agree” or “completely agree”).

Bivariate zero-order correlations for the study variables varied with respect to strength (Table 2). The strongest correlation was between the students’ behavioral and emotional engagement (r = .62). The lowest—albeit significant and positive—correlation was found for TGSM and academic achievement (r = .08). A relatively low correlation was also found between emotional engagement and academic achievement (r = .18).

3.2 Structural equation modeling

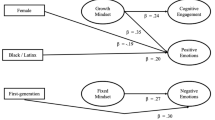

The structural model (presented in Fig. 1) yielded a good fit to the data: χ2 = 1794.34 (473), RMSEA; 0.04 (90% CI, 0.04–0.05), CFI; 0.95, TLI; 0.95, SRMR; 0.03). Regarding research question 2 and in support of H2a, a direct and relatively strong association was observed between TSGM and students’ perceived growth mindset (β = 0.44, p < .001). Moreover, in alignment with the third research question and in support of H3a, the results suggested that TSGM and behavioral engagement were directly associated (β = 0.28, p < .001), as were TSGM and emotional engagement (β = 0.28, p < .001). Regarding research question 4 and in line with H4, a direct association was detected between students’ perceived growth mindset and academic achievement (β = 0.17, p < .001) as well as between students’ growth mindset and behavioral engagement (β = 0.47, p < .001) and between perceived growth mindset and emotional engagement (β = 0.40, p < .001). A direct relationship was further observed between behavioral engagement and academic achievement (β = 0.26, p < .001). No significant path emerged between TSGM and academic achievement or between achievement and students’ perceived emotional engagement.

Students’ perceived TSGM explained 21% of the variance in students’ perceived growth mindset, whereas these two variables accounted for somewhat more with respect to emotional engagement (34%). However, most of the variance for these variables was explained by behavioral engagement (43%), while for academic achievement, the explained variance was 31%.

3.2.1 Indirect effects

Regarding RQ3 and in support of H3b, an indirect effect was observed between TSGM and behavioral engagement via students’ growth mindset (β = 0.21, p < .05, 95% CI 0.17–0.26). An indirect path between TSGM and emotional engagement via students’ growth mindset was also evident (β = 0.18, p < .05, 95% CI 0.14–0.22).

Regarding research question 4, the results aligned with H4a and b, in which indirect effects were found for several of the paths from TSGM to academic achievement. A significant coefficient occurred via behavioral engagement (β = 0.07, p < .05, 95% CI 0.04–0.10) and via students’ growth mindset to academic achievement (β = 0.07, p < .05, 95% CI 0.04–0.11). The serial indirect path from TSGM to academic achievement via students’ growth mindset and behavioral engagement was slightly weaker (β = 0.05, p < .04, 95% CI 0.03–0.08). The serial paths via emotional engagement to academic achievement (as shown in Table 3) showed no indirect association with academic achievement in the current structural model.

4 Discussion

Research on students’ perceived teacher support for growth mindset (TSGM) is relatively scarce (see, e.g., Rissanen et al., 2021). The present study developed a measure to assess students’ perceptions of their teachers’ classroom pedagogical practice that supports growth mindset that yielded good psychometric properties. In essence, the measure assessed the extent to which students perceived their teachers to encourage incremental beliefs regarding intelligence or academic ability, to seek learning challenges and opportunities to learn from failures, to apply various strategies in their learning, and to avoid comparison with others. Using this scale, the present study sought to gain new knowledge regarding students’ perceptions of TSGM. Students’ perceived level of growth mindset was also assessed (RQ1). Latent structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the associations between TSGM and students’ perceived growth mindset (RQ2) and between TSGM and academic engagement (behavioral and emotional), both directly and indirectly, via growth mindset (RQ3). Finally, the paths between all these variables and academic achievement were examined (RQ4; see Fig. 1). The results are discussed below.

4.1 Students’ perceptions of teachers’ support for growth mindset and their growth mindset

The first research question concerned students’ perceptions of TSGM and their growth mindset. Most students agreed that their teachers’ pedagogical classroom practice supported their growth mindset with respect to learning. Thus, the results may reflect the fact that many Norwegian lower secondary school teachers implement a growth mindset pedagogy in the classroom. By contrast, previous research has suggested that teachers’ pedagogical classroom practices are characterized by a focus on achievement that promotes a fixed-oriented mindset among students (Hecht et al., 2021). Nonetheless, operationalizing a growth mindset pedagogy in the classroom entails more than simply promoting beliefs about intellectual abilities (Dweck & Yeager, 2019; Rissanen et al., 2019): the present study assessed students’ perceptions of emotionally supportive teachers who help and encourage them to identify suitable strategies for learning and who focus on individual learning goals that facilitate a mastery-oriented learning environment. In support of this, previous research suggests that Norwegian adolescent students tend to perceive their teachers as facilitating a mastery-oriented learning climate (Stornes et al., 2008). A positive learning climate, when aligned with good classroom practice, may explain why most students perceive their teachers as supporting a growth mindset.

The vast majority of students had scores for perceived growth mindset that fell within the agreement range. The categorized mean score indicates that approximately 20% of the students slightly agreed, approximately 35% quite agreed, and approximately 35% completely agreed that they had a growth mindset. These findings may indicate that a clear majority of Norwegian lower secondary students are optimistic regarding their capacity for learning and their ability to progress. However, it is likely that the “slightly agree” group and possibly some of the “quite agree” group have a fragile growth mindset, suggesting that mindset is situational and that some academic circumstances are less conducive to fostering a growth mindset. Moreover, the results also reflect those one in ten students who disagreed about having a growth mindset, which may align with the suggested sub-groups of lower-achieving students who perceive themselves as having a fixed mindset with respect to learning (e.g., Sisk et al., 2018). Given that little is known about adolescent students’ levels of growth mindset, the present study’s findings primarily address the need for more research within the educational context.

4.2 Teacher support for students’ mindsets and students’ growth mindset

In line with our expectations and what was hypothesized (H2a), a relatively strong direct path was identified between TSGM and the students’ perceived growth mindset. Although mindset is believed to be rather stable, research also suggests that it can be stimulated and may even change across time (Abiola & Dhindsa, 2012; Blackwell et al., 2007; Claro et al., 2016; Fraser, 2018). Interventions aimed at conveying to students that academic abilities are malleable have met with some success (Dweck & Yeager, 2019; Savvides & Bond, 2021). In line with previous studies, the present study’s findings may therefore suggest that teachers’ pedagogical classroom practice has the potential to promote a growth mindset in their students (Schmidt et al., 2015). When students perceive that their teachers encourage them to focus on the learning process, use various learning strategies, and inspire them to attempt challenging learning assignments and learn from their mistakes (Rissanen et al., 2019), they may be more attuned to such an approach to learning, and this, in turn, may stimulate a growth mindset. In support of this notion, a recent controlled intervention study among undergraduate students found that the treated group, who received teaching rooted in a growth mindset pedagogy, increased their growth mindset by 3.4% (Sahagun et al., 2021). However, further research is required to investigate the causal relationship between TSGM and students’ perceived growth mindset. Similarly, further research is required to test the effects of a learning environment that aims to promote a growth mindset.

4.3 The role of teacher support for growth mindset in academic engagement

Direct positive paths were identified between TSGM and behavioral and emotional engagement (H3a). These findings suggest that TGSM can nurture behavioral and emotional engagement independently of promoting students’ growth mindset (Porter et al., 2022). Moreover, it is likely that TSGM—as operationalized in this study—captures support for a spectrum of educational motivational aspects that goes beyond simply inspiring the belief that intellectual abilities can be developed (Rissanen et al., 2019; Ronkainen et al., 2019; Sahagun et al., 2021) and that growth mindset pedagogy includes a range of supportive teacher behaviors that promote positive attitudes, learning behaviors, and experiences but that are not invariably implemented in combination with stimulating a growth mindset—for example, encouraging effort and endurance as well as supporting the use of different learning strategies when students are faced difficult learning tasks are believed to stimulate behavioral actions and engagement (Furrer & Skinner, 2003), which may occur without affecting students’ growth mindset. Concerning emotional engagement, teachers’ practices that alleviate students’ academic concerns by emphasizing the value of learning in its own right and as an individual process may fulfill a similar function. This bears certain similarities to the characteristics of a mastery climate (Valentini & Rudisill, 2006), which have previously been shown to fuel students’ emotional engagement (Mih et al., 2015; Skinner et al., 2009). By contrast, competitive learning contexts that focus exclusively on results may cause some students to feel inadequate and unable to succeed, highlighting the importance of creating an environment that emphasizes the value of learning for the individual and imbues them with a sense of autonomy with respect to their learning (Ronkainen et al., 2019).

TSGM also exhibited relatively strong indirect relationships with behavioral and emotional engagement via students’ perceived growth mindset. This was likely due to the relatively substantial associations between growth mindset and the two aspects of academic engagement as well as the relatively substantial association between TSGM and growth mindset. The findings thus support our assumption that TSGM can stimulate academic engagement by enhancing students’ beliefs that their abilities can be developed.

4.4 Teachers’ support for growth mindset and its links with academic achievement

The indirect relationship between TSGM and academic achievement via students’ perceived growth mindset supports H4a. The link between students’ growth mindset and achievement may cohere around the notion that having a growth mindset supports perseverance in the face of particularly demanding assignments (Yeager & Dweck, 2012) and nurtures students’ beliefs in their ability to cope academically, which positively affect academic achievement (Claro et al., 2016). With that said, existing findings regarding students’ growth mindset and academic achievement are somewhat inconsistent, and despite disagreement among scholars (e.g., Macnamara & Burgoyne, 2022), the link between growth mindset and achievement has primarily been found for lower achieving students (e.g., Sisk et al., 2018). Nonetheless, few studies have investigated how students’ perceptions of classroom pedagogy by TSGM influence their mindset and academic achievement. Given our notion that it entails more than simply inspiring the individual student toward a growth mindset (Dweck & Yeager, 2019), the present study’s findings suggest that the additional contextual aspects facilitated by the teacher also play a role in mindset and academic achievement (Porter et al., 2022; Yeager et al., 2022).

A positive indirect path was also observed for TSGM and academic achievement via behavioral engagement (H4b). These findings are in line with previous empirical results suggesting that students’ perceptions of their teachers’ pedagogical practices as supportive with respect to challenging learning activities can promote their engagement in learning (Skinner et al., 2009), which, in turn, are linked to higher academic achievement (Froiland & Worrell, 2016; Seaton, 2018).

Significant paths were also found for TSGM via growth mindset and via behavioral engagement with academic achievement (H4b). The serial intermediate role of growth mindset and behavioral engagement, in addition to teachers’ behavioral efforts, may also involve students’ beliefs that academic effort is important (Dweck, 2007), supporting the suggested path via behavioral engagement to academic achievement (Furrer & Skinner, 2003).

By contrast, our findings regarding the direct and indirect paths from emotional engagement to academic achievement were not significant, even when intermediately bootstrapped. Previous findings regarding these links have been somewhat mixed and have suggested a direct and positive path between emotional engagement and academic achievement (Lei et al., 2018), while also indicating that emotional engagement is not directly related to academic achievement (e.g., Sagayadevan & Jeyaraj, 2012). The most likely explanation for the present findings is that students’ emotional engagement fuels their effort and endurance (behavioral engagement) and thus enhances academic achievement. The relatively strong correlation between emotional and behavioral engagement supports this interpretation.

4.5 Methodical considerations

The present study’s strength lies in its relatively large sample size and its use of latent estimations in multivariate latent structural modeling. The concurrent and discriminant validity of the study variables was ensured using CFA. An adequate fit for the measurement models supported good internal validity and reliability. Low intraclass correlations (ICC) and design effects for study variables indicated no need for multilevel analysis; instead, the type complex was applied in estimation, with the standard errors adjusted due to the clustered nature of the data (i.e., the students were nested in classes). Nonetheless, the study’s design also has several limitations. First, all data were collected from a single time point and only capture a single moment, providing no evidence for a temporal or causal relationship between the study variables. Interpretation of the results suggesting the directions specified in the SEM model is based on theory and must therefore be interpreted with caution. To our knowledge, however, few previous studies have investigated the role of teachers’ support for a growth mindset pedagogy in the educational context. Further research is needed on how classroom pedagogy supports engagement and achievement among adolescent students. Future studies should investigate TSGM over a longer period of time in addition to exploring its long-term role on students’ growth mindset, academic engagement, and achievement.

4.6 Concluding remarks and implications

This study presents key findings pertaining to students’ perceived TGSM and its relationships with students’ growth mindset, academic engagement (behavioral and emotional), and academic achievement. Growth mindset and engagement were examined as intermediate variables. Above all, a strong link between TSGM and students’ growth mindset supports the notion that teachers in lower secondary school have the potential to stimulate a growth mindset in their students. The application of a growth mindset pedagogy in the classroom may also inspire students’ growth mindset and, thereby, activate behavioral engagement. Interestingly, the findings suggest that TSGM has the potential to enhance academic engagement both by supporting growth mindset and independently of this, potentially indicating that TSGM stimulates student motivation in multiple ways. This may be crucial in lower secondary school, a time when students’ motivation and engagement tend to decline. Finally, the indirect relationship between TSGM and academic achievement via students’ growth mindset and behavioral engagement may suggest that growth mindset pedagogy classrooms may potentially serve as a means of promoting academic achievement in lower secondary school. However, it should be borne in mind that this study was cross-sectional and that any conclusions regarding the influence of teacher support on growth mindset warrant further research with experimental or quasi-experimental designs.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abiola, O. O., & Dhindsa, H. S. (2012). Improving classroom practices using our knowledge of how the brain works. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 7(1), 71–81.

Asparouhov, T., Muthén, B., & Muthén, B. (2006). Robust chi square difference testing with mean and variance adjusted test statistics. Matrix, 1(5), 1–6.

Bakken, A. (2022). Ungdata 2022. Nasjonale resultater [Youth data 2022 Report. National results]. NOVA Rapport 5/22. Oslo: NOVA, OsloMet. Retrived from, https://www.statmodel.com/download/webnotes/webnote10.pdf

Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x

Bostwick, K. C., Collie, R. J., Martin, A. J., & Durksen, T. L. (2020). Teacher, classroom, and student growth orientation in mathematics: A multilevel examination of growth goals, growth mindset, engagement, and achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 94, 103100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103100

Bru, E., Virtanen, T., Kjetilstad, V., & Niemiec, C. P. (2021). Gender differences in the strength of association between perceived support from teachers and student engagement. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(1), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1659404

Burnette, J. L., Billingsley, J., Banks, G. C., Knouse, L. E., Hoyt, C. L., Pollack, J. M., & Simon, S. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of growth mindset interventions: For whom, how, and why might such interventions work? Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 174–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000368

Cai, J., Wen, Q., Qi, Z., & Lombaerts, K. (2023). Identifying core features and barriers in the actualization of growth mindset pedagogy in classrooms. Social Psychology of Education, 26(2), 485–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09755-x

Chou, C.-P., & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 37–55). Sage Publications Inc.

Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(31), 8664–8668. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1608207113

Dweck, C. S. (2007). Boosting achievement with messages that motivate. Education Canada, 47(2), 6–10.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2009). Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Vol. 1. Individual bases of adolescent development (pp. 404–434). Wiley.

Eriksen, E. V., & Bru, E. (2023). Investigating the links of social-emotional competencies: Emotional well-being and academic engagement among adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 67(3), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2021.2021441

Fraser, D. M. (2018). An exploration of the application and implementation of growth mindset principles within a primary school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(4), 645–658. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12208

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Froiland, J. M., & Worrell, F. C. (2016). Intrinsic motivation, learning goals, engagement, and achievement in a diverse high school. Psychology in the Schools, 53(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21901

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.148

Gaumer Erickson, A., Soukup, J., Noonan, P., & McGurn, L. (2016). Self-efficacy questionnaire. In S. Amy, G. Erickson, & P. M. Noonan (Eds.), The skills that matters: Teaching intrapersonal and interpersonal competence in any classroom (pp. 175–176). Corvin.

Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2017). The origins of children’s growth and fixed mindsets: New research and a new proposal. Child Development, 88(6), 1849–1859. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12955

Hecht, C. A., Yeager, D. S., Dweck, C. S., & Murphy, M. C. (2021). Beliefs, affordances, and adolescent development: Lessons from a decade of growth mindset interventions. In J. J. Lockman (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 61, pp. 169–197). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2021.04.004

Honicke, T., & Broadbent, J. (2016). The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 17, 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.11.002

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Chiu, M. M. (2018). The relationship between teacher support and students’ academic emotions: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, Section Educational Psychology, 8, 2288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02288

Lin-Siegler, X., Ahn, J. N., Chen, J., Fang, F. F. A., & Luna-Lucero, M. (2016). Even Einstein struggled: Effects of learning about great scientists’ struggles on high school students’ motivation to learn science. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(3), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000092.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

Macnamara, B. N., & Burgoyne, A. P. (2022). Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychological Bulletin, 149(3-4), 133–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000352

Macnamara, B. N., & Rupani, N. S. (2017). The relationship between intelligence and mindset. Intelligence, 64, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2017.07.003

Markussen, E., Frøseth, M. W., & Sandberg, N. (2011). Reaching for the unreachable: Identifying factors predicting early school leaving and non-completion in Norwegian upper secondary education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(3), 225–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.576876

Meece, J. L., Anderman, E. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2006). Classroom goal structure, student motivation, and academic achievement. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070258

Mesler, R. M., Corbin, C. M., & Martin, B. H. (2021). Teacher mindset is associated with development of students’ growth mindset. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 76, 101299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101299

Mih, V., Mih, C., & Dragoş, V. (2015). Achievement goals and behavioral and emotional engagement as precursors of academic adjusting. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.243

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

Niiya, Y., Crocker, J., & Bartmess, E. N. (2004). From vulnerability to resilience: Learning orientations buffer contingent self-esteem from failure. Psychological Science, 15(12), 801–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00759.x

Patterson, M. M., Kravchenko, N., Chen-Bouck, L., & Kelley, J. A. (2016). General and domain-specific beliefs about intelligence, ability, and effort among preservice and practicing teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.06.004

Pekrun, R. (2016). Academic emotions. In K. R. Wentzel & D. B. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (2nd ed., pp. 120–144). Routledge.

Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). Academic emotions and student engagement. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 259–282). Springer.

Porter, T., Catalán Molina, D., Cimpian, A., Roberts, S., Fredericks, A., Blackwell, L. S., & Trzesniewski, K. (2022). Growth-mindset intervention delivered by teachers boosts achievement in early adolescence. Psychological Science, 33(7), 1086–1096. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211061109

Rege, M., Hanselman, P., Solli, I. F., Dweck, C. S., Ludvigsen, S., Bettinger, E., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Walton, G., & Duckworth, A. (2020). How can we inspire nations of learners? An investigation of growth mindset and challenge-seeking in two countries. American Psychologist, 76(5), 755–767. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000647

Régner, I., Loose, F., & Dumas, F. (2009). Students’ perceptions of parental and teacher academic involvement: Consequences on achievement goals. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24(2), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173016

Rissanen, I., Kuusisto, E., Tuominen, M., & Tirri, K. (2019). In search of a growth mindset pedagogy: A case study of one teacher’s classroom practices in a Finnish elementary school. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.10.002

Rissanen, I., Laine, S., Puusepp, I., Kuusisto, E., & Tirri, K. (2021). Implementing and evaluating growth mindset pedagogy—A study of Finnish elementary school teachers. Frontiers in Education, 6, 753698. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.753698

Roksa, J., & Potter, D. (2011). Parenting and academic achievement: Intergenerational transmission of educational advantage. Sociology of Education, 84(4), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711417013

Ronkainen, R., Kuusisto, E., & Tirri, K. (2019). Growth mindset in teaching: A case study of a Finnish elementary school teacher. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 18(8), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.18.8.9

Sagayadevan, V., & Jeyaraj, S. (2012). The role of emotional engagement in lecturer-student interaction and the Impact on academic outcomes of student achievement and learning. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 12(3), 1–30.

Sahagun, M. A., Moser, R., Shomaker, J., & Fortier, J. (2021). Developing a growth-mindset pedagogy for higher education and testing its efficacy. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 4(1), 100168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100168

Savvides, H., & Bond, C. (2021). How does growth mindset inform interventions in primary schools? A systematic literature review. Educational Psychology in Practice, 37(2), 134–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12955

Schmidt, J. A., Shumow, L., & Kackar-Cam, H. (2015). Exploring teacher effects for mindset intervention outcomes in seventh-grade science classes. Middle Grades Research Journal, 10(2), 17–32.

Seaton, F. S. (2018). Empowering teachers to implement a growth mindset. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1382333

Sisk, V. F., Burgoyne, A. P., Sun, J., Butler, J. L., & Macnamara, B. N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29(4), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617739704

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233

Statistics Norway. (2023). Retrieved from, https://www.ssb.no/a/metadata/definisjoner/variabler/solr.cgi?q=skalapoeng&ref=conceptvariable&sort=score+desc

Steiger, A. E., Allemand, M., Robins, R. W., & Fend, H. A. (2014). Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(2), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035133

Steinmayr, R., Dinger, F. C., & Spinath, B. (2012). Motivation as a mediator of social disparities in academic achievement. European Journal of Personality, 26(3), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.842

Steinmayr, R., Meiǹer, A., Weideinger, A. F., & Wirthwein, L. (2014). Academic achievement. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0108

Stornes, T., Bru, E., & Idsoe, T. (2008). Classroom social structure and motivational climates: On the influence of teachers’ involvement, teachers’ autonomy support and regulation in relation to motivational climates in school classrooms. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52(3), 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830802025124

Tipton, E., Bryan, C., Murray, J., McDaniel, M. A., Schneider, B., & Yeager, D. S. (2023). Why meta-analyses of growth mindset and other interventions should follow best practices for examining heterogeneity: Commentary on Macnamara and Burgoyne (2023) and Burnette et al. (2023). Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000384

Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291170

Valentini, N. C., & Rudisill, M. E. (2006). Goal orientation and mastery climate: A review of contemporary research and insights to intervention. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 23, 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2006000200006

Wang, C. J., Liu, W. C., Kee, Y. H., & Chian, L. K. (2019). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: Understanding students’ motivational processes using the self-determination theory. Heliyon, 5(7), e01983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01983

Wang, M. T., Chow, A., Hofkens, T., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2015). The trajectories of student emotional engagement and school burnout with academic and psychological development: Findings from Finnish adolescents. Learning and Instruction, 36, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.11.004

Wang, M. T., & Holcombe, R. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 633–662. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209361209

Wäschle, K., Allgaier, A., Lachner, A., Fink, S., & Nückles, M. (2014). Procrastination and self-efficacy: Tracing vicious and virtuous circles in self-regulated learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.09.005

Wu, Z. (2019). Academic motivation, engagement, and achievement among college students. College Student Journal, 53(1), 99–112.

Yeager, D. S., Carroll, J. M., Buontempo, J., Cimpian, A., Woody, S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Murray, J., Mhatre, P., & Kersting, N. (2022). Teacher mindsets help explain where a growth-mindset intervention does and doesn’t work. Psychological Science, 33(1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211028984

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.722805

Yeager, D. S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G. M., Murray, J. S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Tipton, E., Schneider, B., Hulleman, C. S., Hinojosa, C. P., Paunesku, D., Romero, C., Flint, K., Roberts, A., Trott, J., Iachan, R., Buontempo, J., Yang, S. M., Carvalho, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature, 573(7774), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y

Yu, J., Kreijkes, P., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2022). Students’ growth mindset: Relation to teacher beliefs, teaching practices, and school climate. Learning and Instruction, 80, 101616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101616

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Stavanger & Stavanger University Hospital. Norwegian Research Council. Project number: 299166.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by LV and EB. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LV and both authors commented of various versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

To ensure that the present study adheres to the proper guidelines for the protection of human subjects, the study was formally approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD).

Consent to participate

Only students with written consent from parents or guardians were allowed to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

All participant of this study had a signed consent from parents or guardian allowing for publication of data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Overview of psychometric properties for measurement models of each construct

Academic achievement | SRMR = 0.01 | RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI (0.03–0.08) | CFI = 1.00 | TLI = 0.99 | α = 0.89 | Factor loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

English | 0.68 | |||||

Math | 0.80 | |||||

Natural sciences | 0.86 | |||||

Norwegian | 0.72 | |||||

Social sciences | 0.86 | |||||

Behavioral engagement | SRMR = 0.03 | RMSEA = 0.07, 90% CI (0.06–0.09) | CFI = 0.98 | TLI = 0.96 | α = 0.93 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I have tried hard to do well in school | 0.80 | |||||

In class, I have worked as hard as I can | 0.86 | |||||

I have paid attention in class | 0.86 | |||||

When I’m in class, I have listened very carefully | 0.84 | |||||

I have worked purposefully with my schoolwork | 0.90 | |||||

I have asked for help when there is something I do not understand | 0.64 | |||||

When I’m in class, I participate in class discussions | 0.69 | |||||

Emotional engagement | SRMR = 0.01 | RMSEA = 0.06, 90% CI (0.04–0.07) | CFI = 0.99 | TLI = 0.99 | α = 0.96 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I have enjoyed keeping up with my schoolwork | 0.89 | |||||

I think it has been fun to work with the subjects | 0.93 | |||||

The subjects we have studied at school have interested me | 0.91 | |||||

I think the schoolwork has been enjoyable or pleasurable | 0.93 | |||||

I think most of the schoolwork has been interesting or useful | 0.88 | |||||

When we have worked on something in class, I have become engaged | 0.86 | |||||

Students’ growth mindset | SRMR = 0.02 | RMSEA = 0.08 90% CI (0.06–0.10) | CFI = 0.98 | TLI = 0.95 | α = 0.92 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I believe hard work pays off | 0.82 | |||||

My ability grows with effort | 0.89 | |||||

I believe that the brain can be developed like a muscle | 0.79 | |||||

I think that no matter who you are, you can significantly change your level of talent | 0.84 | |||||

I can change my basic level of ability considerably | 0.84 | |||||

Teachers’ support for students’ mindsets | SRMR = 0.02 | RMSEA = 0.07 90% CI (0.06–0.09) | CFI = 0.96 | TLI = 0.94 | α = 0.87 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The teachers have encouraged me to try to solve demanding school assignments | 0.76 | |||||

The teachers have encouraged me to keep trying and not give up | 0.82 | |||||

The teachers have said that making mistakes provides me with an opportunity to learn | 0.71 | |||||

The teachers have encouraged me to try new ways of solving tasks if the first one does not work | 0.76 | |||||

The teachers have said that I should focus on my development and not on comparing myself to others | 0.75 | |||||

The teachers have encouraged me to ask for help when I need it | 0.69 | |||||

The teachers have said that by solving challenging tasks, the brain is trained like a muscle | 0.64 | |||||

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vestad, L., Bru, E. Teachers’ support for growth mindset and its links with students’ growth mindset, academic engagement, and achievements in lower secondary school. Soc Psychol Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09859-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09859-y