Abstract

This study explored relations between teachers’ perceptions of sharing educational goals and values with their colleagues (shared values), job satisfaction, and motivation to leave the teaching profession. The extent to which these associations were mediated through indicators of psychological need satisfaction (belonging, autonomy, and competence) was also examined. Participants were 1145 Norwegian teachers. SEM analyses showed that shared values were positively associated with all indicators of psychological need satisfaction. Shared values were also indirectly associated with general job satisfaction, mediated through perceived belonging and competence. In turn, job satisfaction was strongly and negatively associated with motivation to leave.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction and purpose

For several decades, much teacher research has focused on causes of stress in the teaching profession, for instance, workload, discipline problems, interpersonal conflicts, and role ambiguity (Betoret, 2009; Fernet et al., 2012; Hakanen et al., 2006; Klassen & Chiu, 2011; Richards et al., 2016; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011, 2021a). Such stressful working conditions have been shown to be associated with emotional exhaustion, reduced engagement, intentions of leaving the teaching profession and with actual teacher turnover (Boyd et al., 2011; Fiegener & Adams, 2022; Ford et al., 2019, Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2016, 2018; Van Den Broeck et al., 2008).

Lately, researchers have increasingly studied aspects of the work or the work environment that may be positively associated with teacher motivation, job satisfaction, and wellbeing. Such aspects are often termed job resources. Different indicators of teacher motivation and well-being have been shown to be associated with several job resources, for instance positive social relations with colleagues and supervisors, a sense of mutual trust, a supportive social environment, and teacher autonomy, but also internal resources like teacher self-efficacy and collective teacher efficacy (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011, 2021a; Fiegener & Adams, 2022; Fuller et al., 2016; Hakanen et al., 2006; Leung & Lee, 2006).

Based on self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017), satisfaction of basic psychological needs (need satisfaction) is also expected to lead to job satisfaction, motivation, and well-being. According to self-determination theory (SDT), people have three basic psychological needs: the need to belong, the need for autonomy, and the need to be competent. Since all human beings are assumed to have these needs, the question in SDT is not how strong the psychological needs are, but to what extend they are satisfied or thwarted. Empirical research supports the notion that need satisfaction in the workplace is associated with positive outcomes like job satisfaction, well-being, and work-related motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

A few studies of teachers also indicate that shared educational goals and values, teachers’ feeling that their educational goals and values are in congruence with the goals and values that are emphasized at the school and by their colleagues, are predictive of higher teacher well-being (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011, 2018, 2021b; Yang et al., 2022). For instance, in a study of 760 Norwegian teachers Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2021b) found that teachers’ feeling of sharing educational goals and values with their colleagues correlated positively with their feeling of belonging and autonomy as well as with job satisfaction.

Based on these studies, the present study aimed at exploring how shared educational goals and values were related to teachers’ feeling of belonging, autonomy, competence, job satisfaction, and motivation to leave the teaching profession.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Self-determination theory

Motivational researchers have long highlighted the importance of satisfying three psychological needs for human motivation and wellbeing: the need to belonging (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), the need for autonomy (de Charms, 1968), and the need to feel competent (Bandura, 1997; White, 1959). These psychological needs form the core of the SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p. 9). SDT is concerned with human growth, well-being, and motivation. An assumption underlying the theory is that people are inherently curious, physical active, and social beings. It builds on the assumption that well-being and motivation are affected by peoples’ interactions with their social environment (Ryan & Deci, 2017). It is through interaction with other people in one’s social environment that the basic psychological needs may be satisfied or frustrated. Because the basic psychological needs are important to everyone, Ryan and Deci (2017) underscore that outcomes like motivation and indicators of well-being cannot be predicted from the strength of the needs, but “… from the extent to which social contexts are or have been either supporting or thwarting of need satisfaction” (p. 89).

2.1.1 The need to belong

Baumeister and Leary (1995) conceptualized the need to belong as a deeply rooted human motivation. It refers to a desire to be accepted, respected, and valued (Allen et al., 2022). Ryan and Deci (2017) use the term relatedness, which in their conceptualization concerns the feeling of being socially connected to close others or to be a significant member of a social group.

Empirical studies reveal that satisfaction of the need to belong is negatively associated with depression (Parr et al., 2020) and positively associated with emotional wellbeing (Allen et al, 2018; Arslan, 2021; Arslan & Allen, 2021). Also, supportive colleagues and a supportive school administration predict teacher well-being and engagement positively and motivation to leave the teaching profession negatively (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2018). We therefore expected that teachers’ perceptions of belonging at the school where they were teaching would be positively associated with job satisfaction and negatively associated with motivation to leave.

2.1.2 The need for autonomy

According to Collie (2022) autonomy refers to a sense of having a say in how one thinks, acts, and feels in social and emotional situations and interactions. Similarly, Ryan and Deci (2017) note that autonomy refers to a feeling that one’s actions are self-endorsed (Ryan & Deci, 2017). However, Ryan and Deci (2017) also emphasize that autonomy is not the same as independence, and that the core of autonomy is that one’s actions are congruent with one’s interests and values. In previous research on Norwegian teachers, perceived autonomy has been shown to predict job satisfaction and engagement positively (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2009, 2014, 2017a, 2021a) and to predict emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit negatively (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2009, 2017a, 2021a). Based on previous research (for an overview, see Fiegener & Adams, 2022), we expected autonomy to be positively associated with job satisfaction and negatively associated with motivation to leave the teaching profession.

2.1.3 The need to feel competent

Feeling competent refers to the sense of being effective in one’s undertakings and that one perceives one’s own actions to lead to desired outcomes (Collie, 2022; Ryan & Deci, 2017), which we conceptualize as domain-specific self-perceived abilities. In educational and psychological research, self-perceived abilities have been measured as both domain-specific self-efficacy and domain-specific self-concept (Bong & Skaalvik, 2003). In teacher research, both teaching-related self-concept and self-efficacy have been shown to be predictive of job satisfaction, motivation, and well-being (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2013; Caprara et al., 2006; Granziera & Perera, 2019; Zhu et al., 2018). In the present study, we expected the feeling of competence to be positively associated with job satisfaction and negatively associated with motivation to leave the teaching profession. Teachers’ subjective feeling of teaching competence was conceptualized in this study as self-perceived teaching abilities.

2.2 Shared values

Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2011, 2021b) defined value consonance, which we will term shared values, as teachers’ perceptions of sharing educational goals and values that are emphasized at their schools. Shared values are not defined as particular goals and values, but by a common understanding of educational goals and values. Thus, shared values mean that the teachers at a school feel that their educational goals and values, irrespective of what these goals and values may be, are in congruence with the goals and values emphasized by their colleagues and the school administration, for instance what goals should be pursued and what content should be emphasized. Shared goals and norms are also recognized as key elements of teacher social cohesion (Fiegener & Adams, 2022).

Because teaching is a profession which is typically driven by values, ethical motives, or intrinsic motivation (Sahlberg, 2010), we expect shared values to be particularly important in this profession. According to Chang (2009), teachers explicitly or implicitly set goals for their teaching. Also, in their daily work teachers communicate and represent values (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). This is especially true in Norwegian schools today because teachers often work in teacher teams, setting goals, choosing contents, and planning the actual teaching.

Teachers who experience that they do not share the prevailing goals and values at the school where they are teaching likely find themselves in what Rosenberg (1979) termed “a dissonant context”—in this case in a dissonant value context. Some of these teachers may feel pressured to teach in accordance with goals and values that they do not endorse, which may both enhance their feeling of being in a dissonant value context and result in a cognitive dissonance between their own values and their actual teaching. Alternatively, some teachers may choose to teach in accordance with their own goals and values, which deviate from the prevailing values at school. These teachers will also be in a dissonant context, in this case in a more visible dissonant context.

Being in a dissonant context may have serious implications for a person’s wellbeing and motivation. We suggest that being in a dissonant context may result in a lack of satisfaction of the basic psychological needs for belonging, autonomy, and competence. According to Rosenberg (1977, 1979) being in a dissonant context may result in a feeling of not belonging, a feeling that one does not fit, or that one is somehow wrong. A dissonant value context will likely lead to lower feeling of both belonging and competence because a social context is a communication environment. In Rosenberg’s (1977) terms, a social context is a fund of messages, some communicated directly and others informally and unintentionally. Teachers in a dissonant value context will likely receive less social support, both emotional and instrumental support, which may affect both their feeling of belonging and competence.

Some teachers in a dissonant value context may feel pressured to teach towards goals and values that are not congruent with their personal values. As already noted, the experience of autonomy partly depends on the extent to which one's actions are congruent with one's own interests and values (Ryan & Deci, 2017). We therefore also suggest that being in a dissonant value context, not sharing the prevailing educational goals and values at school, will be negatively associated with perceived autonomy. In contrast, being in a consonant value context, or sharing prevailing goals and values at school, will likely add to the feeling of autonomy because teachers in a consonant value context more easily can act (teach) in accordance with their personal goals and values.

We also expected shared values to be positively associated with job satisfaction and negatively associated with motivation to leave the teaching profession. One of the questions raised in this study was whether these associations were mediated through higher psychological need satisfaction.

2.3 Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction is commonly conceptualized as the positive or negative evaluative judgments people make about their jobs (Weiss, 1999). In an early presentation, Locke (1976) defined job satisfaction as a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job. Following this conceptualization, Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2010) defined teacher job satisfaction as teachers’ affective reactions to their work or to their teaching role. In empirical research, job satisfaction has been measured both as satisfaction with specific aspects of the job, and as an overall sense of satisfaction with the job (Moe et al., 2010). A problem with the facet-specific approach is that different circumstances may be important to different teachers. As pointed out by Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2010), such measures overlook the fact that the impact of different circumstances on overall job satisfaction is dependent on how important each of the circumstances is to the individual teacher. In this study, we therefore measured teachers’ overall sense of job satisfaction. Empirical research shows that teacher job satisfaction is closely associated with teacher absenteeism, attrition, and motivation to leave the teaching profession (Sargent & Hannum, 2005; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011; Wriqi, 2008; Zembylas & Papanastasiou, 2006). We therefore expected that teacher job satisfaction would predict teachers’ motivation to leave the teaching profession. As noted above, we also expected that perceived belonging, autonomy, and competence would be positively associated with job satisfaction.

2.4 Study overview

One aim of the present study was to examine the extent to which shared goals and values in the teaching profession were associated with teachers’ feeling of belonging, autonomy, and competence. A second aim was to examine relations between (a) shared values, perceived belonging, perceived autonomy, and perceived competence and (b) teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the profession. A third aim was to explore the extent to which associations between shared values and teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the profession were mediated through perceptions of belonging, autonomy, and competence.

The study was designed as a cross-sectional survey and analyzed by means of structural equation modeling. A theoretical model is shown in Fig. 1. The theoretical model builds on the assumption that the association between shared values and job satisfaction is mediated through perceptions of belonging, autonomy, and competence. The model also builds on the assumption that the associations between the indicators of need satisfaction and motivation to leave are mediated through general job satisfaction.

3 Method

The data used in this study was part of a larger data collection conducted by the authors. One of the variables, shared values, is previously analyzed. Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2017b) analyzed associations between shared values and dimensions of teacher burnout, whereas Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2023) analyzed shared values as one dimension of a collective teacher culture construct. Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2023) also explored associations between a collective teacher culture and school goal structure, teacher self-efficacy, and engagement.

3.1 Participants and procedure

Participants in the study were 1145 Norwegian teachers (427 teachers in elementary school, 333 teachers in middle school, and 385 teachers in high school). Thirty-four schools were drawn at random from three counties in central Norway and all teachers in those schools were invited to participate. Eighty-one percent of the teachers at the selected schools participated in the study. Participation was voluntary for both the schools and the individual teachers. Sixty-five percent of the participants were women. The age ranged from 23 to 68 years with a mean age of 45 years and the experiences as teachers ranged from 1 to 47 years with a mean age of 15 years.

Norwegian schools tend to be small, particularly in rural areas. The mean number of teachers from each school were 33.76. At the low end, less than twenty teachers participated from four of the schools, whereas at the high end, more than sixty teachers participated from six of the schools.

A particular period during working hours was set aside for all teachers to fill out the questionnaire at the same time. When the questionnaires were filled out, they were put in envelopes and sealed at the spot to assure the teachers that they were anonymous. Prior to the data collection the teachers were informed that the aim of the study was to explore teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions and their experiences of working as teachers. They were also informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous. Following advice from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, the teachers were informed that they consented to participate by filling out and submitting the questionnaire.

3.2 Instruments

3.2.1 Shared goals and values

Shared values was defined as the degree to which teachers felt that they personally shared the prevailing norms and values at the school where they were teaching. It was measured by means of a previously tested three-item value consonance scale (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). The items were: “My educational values are in accordance with the values which are emphasized at this school”, “My colleagues and I have the same opinion about what is important in education”, and “I feel that this school shares my view of what constitutes good teaching”. Responses were given on a 6-point scale from “Completely disagree” (1) to “Completely agree” (6). In the present study, good internal consistency was achieved (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

3.2.2 Belonging

The teachers’ sense of belonging was measured by means of a three-item scale. The items were: “I feel that I belong at this school”, “It is at this school that I want to teach”, and “I have several good friends among my colleagues at this school”. Responses were given on a 6-point scale from “Completely disagree” (1) to “Completely agree” (6). Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.75.

3.2.3 Autonomy

Perceived autonomy was measured by means of a previously tested three-item scale (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010). The items were: ‘‘In my daily teaching I am free to choose teaching methods and strategies”, “In the subjects that I teach I feel free to decide what content to focus on”, and “I feel that I can influence my working condition”. Responses were given on a 6-point scale from “Completely disagree” (1) to “Completely agree” (6). Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.72.

3.2.4 Competence

Perceived competence was measured by a five-item scale focusing on the teachers’ work-related self-perceived abilities, for instance sense of doing a good and important job and perceiving positive results of their teaching. The items were: “I feel that I am doing a good job”, “I am satisfied with my teaching”, “I feel that I am doing an important job”, “I succeed with my teaching”, and “I daily see positive result of my instruction”. Responses were given on a 6-point scale from “Completely disagree” (1) to “Completely agree” (6). Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.88.

3.2.5 Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured by means of a previously tested four-item scale (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). The items were: “I enjoy working as a teacher”, “I look forward to going to school every day”, “Working as a teacher is extremely rewarding,” and “When I get up in the morning, I cannot wait to go to school”. Responses were given on a 6-point scale from “Completely disagree” (1) to “Completely agree” (6). Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.90.

3.2.6 Motivation to quit

The teachers’ motivation to leave the teaching profession was measured by a three-item motivation to leave scale (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). The items were: ‘‘I wish I had a different job to being a teacher’’, ‘‘If I could choose over again, I would not be a teacher’’, and ‘‘I often think of leaving the teaching profession’’. Responses were given on a 6-point scale from ‘‘Completely disagree’’ (1) to ‘‘Completely agree’’ (6). Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.90.

3.3 Data analysis

We first tested a measurement model by means of confirmatory factor analysis, using the AMOS 23 program. The model specified shared values, belonging, autonomy, competence, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit as separate factors. The purpose of testing the measurement model was to test that the factors specified were independent constructs and ascertain factor loadings. Based on the results of the factor analysis, we computed observed study variables and analyzed descriptive statistics by means of SPSS (statistical means, standard deviations, correlations between the observed variables, and Cronbach’s alphas). We then tested the theoretical model (see Fig. 1), using structural equation modeling (SEM analysis). The theoretical model assumed that teachers’ experiences of need satisfaction mediate the association between shared values and general job satisfaction, and that job satisfaction mediates the associations between need satisfaction and motivation to quit. To test whether there were any unexpected direct associations between shared values and job satisfaction and between the indicators of need satisfaction and motivation to quit, we also conducted a second SEM analysis including these direct paths.

To assess model fit, we used well-established indices, such as CFI, TLI, and RMSEA, in addition to the chi-square test statistics. For the CFI and TLI indices, values greater than 0.90 are typically considered acceptable, and values greater than 0.95 indicate a good fit to the data (Bollen, 1989; Byrne, 2001; Hu & Bentler, 1999). For well-specified models, an RMSEA of 0.06 or less reflects a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Missing values, which only were 0.38 percent of all expected responses, were treated based on maximum likelihood (ML) estimation in the AMOS program (Byrne, 2001). Compared to both listwise and pairwise deletion of missing data and to mean imputation, ML estimation will exhibit the least bias (Little & Rubin, 1989; Muthén et al., 1987; Schafer, 1997).

4 Results

4.1 Confirmatory factor analysis

We first tested the measurement model by means of a confirmatory factor analysis (see data analysis). The model had good fit to the data (χ2 = 174, N = 1145) = 953.699, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.063, CFI = 0.947, TLI = 0.929) and all factor loadings were strong (see Table 1). The factor analysis confirmed that all items were adequate indicators of the respective study variables (shared values, belonging, autonomy, competence, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit).

4.2 Descriptive statistics

Based on the factor analysis, composite study variables were computed. Table 2 shows statistical means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s α, and zero order correlations between these variables. As expected, the correlations between the study variables showed that shared values were positively associated with perceptions of belonging, autonomy, and competence as well as with general job satisfaction, and negatively associated with motivation to leave the teaching profession. Shared values correlated particularly strongly with teachers’ sense of belonging (r. = .49). Motivation to leave the teaching profession was negatively associated with all other variables and most strongly with general job satisfaction (r. = .52).

Because the individual teacher data were nested within schools (multiple teachers stem from the same school), for each variable we estimated the percent of the variance that could be explained by the school level. These analyses were done by means of intraclass correlations (ICC) using the STATA software package version 17.0 Special Edition for estimating the ICC. The results of these analyses are displayed in Table 2. Based on guidelines for what constitutes high ICC (ICC ≥ 0.05; LeBreton & Senter, 2008), these analyses indicated that for shared goals and values (ICC = 6.9%) and especially autonomy (ICC = 15.0%), teachers at the same school had substantially shared perceptions. In contrast, perceptions concerning belonging, competence, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit, did not cluster tightly together. A possible interpretation is that autonomy is the one variable in this study that is most influenced by the policy of the school administration. However, we should note that in Norwegian schools, teachers are working in teams (both grade level teams and school-subject teams). We propose that goals, values and ethos may vary from team to team and that the teacher team to which a teacher belong may be an even more influential environment than the school itself. Because we had no information about team memberships, ICCs within teams could not be computed.

4.3 SEM analysis

The theoretical model was tested by means of a SEM analysis. Only paths from the theoretical model were included in the empirical model (Fig. 2). The data showed good fit to the model (χ2 (182, N = 1145) = 1008.191, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.063, CFI = 0.943, TLI = 0.928). Shared values were positively associated with teachers feeling of belonging (beta = 0.59), autonomy (β = 0.35), and competence (β = 0.29). In turn, these variables were positively associated with job satisfaction (β = 0.39, 0.06, and 0.38, respectively). It should be noted that, although significant, the association between autonomy and job satisfaction was weak. A strong negative association was found between job satisfaction and motivation to quit -0.72). The total indirect effect of shared values on motivation to quit was 0.42.

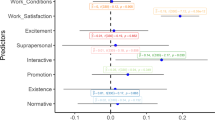

The SEM analysis shown in Fig. 2 indicated that the theoretical model fitted the data well. As already noted, the theoretical model assumed that teachers’ experiences of need satisfaction mediate the associations between shared values and general job satisfaction, and that job satisfaction mediates the associations between need satisfaction and motivation to quit. To test whether there were any unexpected direct associations between shared values and job satisfaction and between the indicators of need satisfaction and motivation to quit, we also conducted a second SEM analysis including these direct paths. This model also had good fit to the data (χ2 (177, N = 1145) = 991.378, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.063, CFI = 0.944, TLI = 0.927). However, only two of the direct paths were significant and the associations were weak. Shared values were directly but weakly associated with job satisfaction (β = 0.12) and belonging was directly and negatively associated with motivation to quit (β = 0.08). Figure 3 shows the result of the second SEM analysis. For simplicity, only significant paths are included in the figure. In the second SEM analysis, the path from autonomy to job satisfaction was no longer significant.

Structural model 2. Note. Direct paths from shared goals and values to job satisfaction and motivation to leave were included. Also, direct paths from belonging, autonomy, and competence to motivation to leave were included. Only significant values are included in the figure. Standardized regression coefficients reported

5 Discussion

As expected, the perception of sharing educational goals and values with one’s colleagues (shared values) correlated positively with measures of perceived belonging, perceived autonomy, and perceived competence, which in this study were used as indicators of basic psychological need satisfaction. Shared values also correlated positively with general job satisfaction and negatively with motivation to leave the teaching profession. Also, all indicators of need satisfaction at work correlated positively with general job satisfaction and negatively with motivation to leave the profession. These results are in accordance with previous findings exploring associations with shared educational goals and values in school (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2018, 2021b; Yang et al., 2022).

The result of the SEM analyses indicated that the association between shared values and job satisfaction primarily was indirect, mediated through two of the indicators of psychological need satisfaction (belonging and competence). The SEM analyses also indicated that the associations between (a) belonging and competence and (b) motivation to leave the teaching profession primarily were indirect, mediated through general job satisfaction. The theoretical model was built on expectations of such mediational processes. These expectations were supported by the first SEM analysis, testing the theoretical model. They were further strengthened by the second SEM analysis showing only two weak direct associations, one between shared goals and values and job satisfaction and one between belonging and motivation to quit.

The study provides a clear indication of the importance of working to develop a common understanding of educational goals and values and a commitment to these values in the teaching staff. It indicates that the perception of sharing goals and values are important prerequisites for teachers’ experiences of belonging, autonomy, and competence, and therefore also for general job satisfaction and motivation to continue in the teaching profession. These findings strengthen and expand previous research indicating that, in the teaching profession, the perception of sharing goals and values predicts teacher engagement (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2018).

Rosenberg explains the importance of contextual consonance (e.g., sharing goals and values) by analyzing possible implications of being in a dissonant context. Being in a dissonant context may result in a feeling of not belonging, a feeling that one does not fit, that one is out of it, somehow wrong (Rosenberg, 1977, 1979). Being in a consonant value context may be particularly important in the teaching profession because it is strongly value oriented.

The results of this study also lend partial support to the self-determination theory (e.g., Ryan & Deci, 2017). The core of this theory is that satisfaction of three basic psychological needs (perceived belonging or relatedness, perceived autonomy, and perceived competence) is associated with motivation and well-being, for instance job satisfaction. Supporting these expectations, the SEM analyses showed that both perceived belonging and perceived competence were positively associated with job satisfaction. However, in this study, the second SEM analysis failed to show a significant association between autonomy and job satisfaction. A possible interpretation of this finding, that should be tested in future research, is that the sharing of important work-related goals and values with one’s colleagues and with the school administration will diminish the impact of work-related autonomy. We suggest that the reason for this is that, in the teaching profession, an important aspect of autonomy is enabling the teachers to work in accordance with their own educational goals and values, which is one of the outcomes of sharing goals and values. This study not only supports the notion of basic psychological need satisfaction, it also indicates that, at least in the teaching profession, sharing educational values is an important determinant of need satisfaction.

A practical implication of the present finings is that a core task for school principals should be to work to develop a common understanding of educational goals and values in the teaching staff. Educational goals and values need to be discussed in order for all teachers to feel committed to work towards common goals and values. Common goals and values do not necessarily require common means and procedures which teachers might experience as a loss of autonomy. However, we suggest that possible means and procedures should be discussed in relation to goals and values to raise teachers’ awareness of relations between goals, values, and educational practices.

Table 2 shows that the teachers’ motivation to leave the profession correlated negatively with all other measures included in the study: shared values, belonging, autonomy, competence, and job satisfaction. However, the SEM analyses indicated that the impact of shared values, perceived belonging and perceived competence on motivation to leave primarily were mediated through job satisfaction.

This study has several limitations. Although the SEM analysis was built on a theoretical model, the study was designed as a cross-sectional survey. Longitudinal studies are needed to draw conclusions about causal relations. Longitudinal studies are also needed to test our interpretation that the impact of shared values on job satisfaction is mediated through teachers’ feeling of belonging and competence. Although the measure of shared values had high internal consistency, it has previously been shown to be part of a broader construct of collective culture (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2021b, 2023). Future research should explore how need satisfaction in the teaching profession is related to this broader construct.

Our interpretations of the findings are partly based on Rosenberg’s (1979) analyses of possible consequences of being in consonant and dissonant contexts. According to Rosenberg, being in a dissonant context may result in a feeling of not belonging whereas being in a consonant context more likely will result in a feeling of belonging. However, our measure of shared values does not provide any information about the teachers’ frames of references. For each teacher, the frame of reference may be the entire teacher collegium or a team of teachers with whom the individual teacher collaborates. In Norwegian schools, the composition of teacher teams is based both on which grades the teachers teach at and which school subjects they teach. Moreover, our measure of shared values was not designed to measure particular values. An important task for future research is to explore both differences in values and teachers’ frames of references for judging if they share the values emphasized at school or by their colleagues.

As already noted, the individual teacher data were nested both within schools and teacher teams. Because our analyses did not take into account school and team membership, relations at the teacher level may be overestimated.

6 Conclusion

This study contributes to an understanding of the role that a common understanding of educational goals and value play in education. The analysis indicated that sharing goals and values are important prerequisites of need satisfaction, which in turn mediates the association between shared goals and values and teacher job satisfaction as well as intentions of leaving the profession. We suggest that a practical implication of these findings is that school leaders should invest time and effort to build a collective school culture characterized by a common understanding of educational goals and values.

Data availability

The data for the current study can be requested from the authors. All reasonable requests will be considered.

References

Allen, K.-A., Gray, D. L., Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (2022). The need to belong: A deep dive into the origins, implications, and future of a foundational construct. Educational Psychology Review, 34(2), 1133–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09633-6

Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Waters, L., & Hattie, J. (2018). What schools need to know about belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Arslan, G. (2021). Loneliness, college belongingness, subjective vitality, and psychological adjustment during coronavirus pandemic: Development of the college belongingness questionnaire. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 5(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.47602/jpsp.v5i1.240

Arslan, G., & Allen, K. A. (2021). School victimization, school belongingness, psychological well-being, and emotional problems in adolescence. Child Indicators Research, 14(4), 1501–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09813-4

Avanzi, L., Miglioretti, M., Velasco, V., Balducci, C., Vecchio, L., Fraccaroli, F., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2013). Cross-validation of the Norwegian Teacher's Self-Efficacy Scale (NTSES). Teaching and Teacher Education, 31, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1004225

Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003) Academic Self-concept and Self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 15(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021302408382

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Freeman.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Betoret, F. D. (2009). Self-efficacy, school resources, job stressors and burnout among Spanish primary and secondary school teachers: A structural equation approach. Educational Psychology, 29(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802459234

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Ing, M., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2011). The influence of school administrators on teacher retention decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 303–333. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210380788

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modelling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Ass.

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44(6), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.001

Chang, M.-L. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: Examining the emotional work of teachers. Educational Psychology Review, 21(3), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-009-9106-y

Collie, R. J. (2022). Social-emotional need satisfaction, prosocial motivation, and students’ positive behavioral and well-being outcomes. Social Psychology of Education, 25(2–3), 399–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09691-w

De Charms, P. C. (1968). Personal Causation: The Internal Affective Determinations of Behavior. Academic Press.

Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senécal, C., & Austin, S. (2012). Predicting intra-individual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(4), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013

Fiegener, A. M., & Adams, C. M. (2022). Instructional program coherence, teacher intent to leave, and the mediating role of teacher psychological needs. Leadership and Policy in Schools. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2021.2022164

Ford, T. G., Olsen, J. J., Khojasteh, J., Ware, J. K., & Urick, A. (2019). Effects of leader support for teacher psychological needs on teacher burnout, commitment, and intent to leave. Journal of Educational Administration, 57(6), 615–634. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-09-2018-0185

Fuller, B., Waite, A., & Torres Irribarra, D. (2016). Explaining teacher turnover: School cohesion and intrinsic motivation in Los Angeles. American Journal of Education, 122(4), 537–567. https://doi.org/10.1086/687272

Granziera, H., & Perera, H. N. (2019). Relations among teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, engagement, and work satisfaction: A social cognitive view. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.02.003

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Klassen, R., & Chiu, M. M. (2011). The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: Influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(2), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002

LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852.

Leung, D. Y. P., & Lee, W. W. S. (2006). Predicting intention to quit among Chinese teachers: differential predictability of the components of burnout Anxiety Stress & Coping. An International Journal, 19(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800600565476

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (1989). The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods and Research, 18(2–3), 292–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189018002004

Locke, W. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. Dunette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1349). Rand-McNally.

Moe, A., Pazzaglia, F., & Ronconi, L. (2010). When being able is not enough The combined value of positive affect and self-efficacy for job satisfaction in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(5), 1145–1153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.02.010

Muthén, B., Kaplan, D., & Hollis, M. (1987). On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrica, 42(3), 431–462.

Parr, E. J., Shochet, I. M., Cockshaw, W. D., & Kelly, R. L. (2020). General belonging is a key predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms and partially mediates school belonging. School Mental Health, 12(3), 626–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09371-0

Richards, K. A. R., Levesque-Bristol, C., Templin, T. J., & Graber, K. C. (2016). The impact of resilience on role stressors and burnout in elementary and secondary teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 19(3), 511–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9346-x

Rosenberg, M. (1977). Contextual dissonance effects: Nature and causes. Psychiatry, 40(3), 205–217.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. Basic Books.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. Guilford Press.

Sahlberg, P. (2010). Rethinking accountability in a knowledge society. Journal of Educational Change, 11(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9098-2

Schafer, J. L. (1997). Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman & Hall.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2009). Does school context matter? Relations with teacher burnout and job satisfaction. Teacher and Teacher Education, 25(3), 518–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.12.006

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(6), 1059–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: Relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychological Reports, 114(1), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.2466/14.02.PR0.114k14w0

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2016). Teacher stress and teacher self-efficacy as predictors of engagement, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to leave the teaching profession. Creative Education, 7(13), 1785–1799. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.713182

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017a). Still motivated to teach? A study of school context variables, stress and job satisfaction among teachers in senior high school. Social Psychology of Education, 20(1), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9363-9

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017b). Dimensions of teacher burnout: Relations with potential stressors at school. Social Psychology of Education, 20(4), 775–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9363-9

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Social Psychology of Education, 21(5), 1251–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9464-8

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2021a). Teacher burnout: relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. A longitudinal study. Teachers and Teaching, 26(7–8), 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1913404

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2021b). Collective teacher culture: exploring an elusive construct and its relations with teacher autonomy, belonging, and job satisfaction. Social Psychology of Education, 24(6), 1389–1406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09673-4

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2023). Collective teacher culture and school goal structure: Associations with teacher self-efficacy and engagement. Social Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09778-y

Van Den Broeck, A., Vansteenkiste, M., De Witte, H., & Lens, W. (2008). Explaining the relationships between job characteristics, burnout, and engagement: The role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Work & Stress, 22(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393672

Weiss, E. M. (1999). Perceived workplace conditions and first-year teachers’ morale, career choice commitment, and planned retention: A secondary analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15(8), 861–879. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00040-2

White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Reciew, 66(5), 297–333.

Wriqi, C. (2008). The structure of secondary school teacher job satisfaction and its relationship with attrition and work enthusiasm. Chinese Education and Society, 40(5), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932400503

Yang, X., Qureshi, A. H., Kuo, Y., Quynh, N. N., Kumar, T., & Wisetsri, W. (2022). Teachers’ value consonance and employee-based brand equity: The mediating role of belongingness and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.900972

Zembylas, M., & Papanastasiou, E. (2006). Sources of teacher job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in Cyprus. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 36(2), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920600741289

Zhu, M., Liu, Q., Fu, Y., Yang, T., Zhang, X., & Shi, J. (2018). The relationship between teacher self-concept, teacher efficacy and burnout. Teachers and Teaching, 24(7), 788–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1483913

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

Obtained from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) which serves as a national ethical research committee.

Informed consent

Participation in this study was voluntary for both the participating schools and for the individual teachers. The teachers were informed that participating was anonymous and voluntary and that they provided consent by filling out and submitting the questionnaire.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skaalvik, E.M., Skaalvik, S. Shared goals and values in the teaching profession, job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: The mediating role of psychological need satisfaction. Soc Psychol Educ 26, 1227–1244 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09787-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09787-x