Abstract

We study the role of the drift effect in the temporal changes of the anisotropy of galactic cosmic rays (GCRs) and the influence of the sector structure of the heliospheric magnetic field on it. We analyze the GCR anisotropy in Solar Cycle 24 and solar minimum 23/24 with negative polarity (\(qA<0\)) for the period of 2007 – 2009 and near minimum 24/25 with positive polarity (\(qA>0\)) in 2017 – 2018 using data of the global network of Neutron Monitors. We use the harmonic analysis method to calculate the radial and tangential components of the anisotropy of GCRs for different sectors (‘+’ corresponds to the positive and ‘−’ to the negative directions) of the heliospheric magnetic field. We compare the analysis of GCR anisotropy using different evaluations of the mean GCRs rigidity related to Neutron Monitor observations. Then the radial and tangential components are used for characterizing the GCR modulation in the heliosphere. We show that in the solar minimum 23/24 in 2007 – 2009 when \(qA<0\), the drift effect is not visibly evident in the changes of the radial component, i.e. the drift effect is found to produce \(\approx 4\)% change in the radial component of the GCR anisotropy for 2007 – 2009. Hence the diffusion dominated model of GCR transport is more acceptable in 2007 – 2009. In turn, near the solar minimum 24/25 in 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\), the drift effect is evidently visible and produces ≈40% change in the radial component of the GCR anisotropy for 2017 – 2018. So in the period of 2017 – 2018 a diffusion model with noticeably manifested drift is acceptable. The results of this work are in good agreement with the drift theory of GCR modulation, according to which, during negative (positive) polarity cycles, a drift stream of GCRs is directed toward (away from) the Sun, thus giving rise to a 22-year cycle variation of the radial GCR anisotropy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Galactic cosmic rays (GCRs) measured at Earth are modulated in the heliosphere by an expanding solar wind (SW). Modulation of GCRs is governed by the convection of SW, inward diffusion of GCRs on the irregularities of heliospheric magnetic field (HMF), drift on the regular HMF and adiabatic cooling of GCRs particles due to extension of SW. GCRs intensity detected near Earth contains the various long- and short-term quasi-periodic variations; see e.g. (Kudela and Sabbah, 2016; Chowdhury, Kudela, and Moon, 2016; Bazilevskaya et al., 2014 and the references therein). The most prominent periodic variations are 22 years, 11 years, 27 days and solar diurnal variation (\(\approx 24\) hours). On the background of the long-term solar modulation: 22 years and 11 years, connected with the global HMF and the solar activity (SA) cycle, respectively, the short-term modulation effects sporadic (e.g. Forbush decreases) and recurrent (\(\approx 27\) days) also take place.

This paper focuses on an anisotropic part of GCRs flux, reflected in the solar diurnal variation (\(\approx 24\) hours wave), being a consequence of the equilibrium state between inward diffusion of GCRs in the HMF in the heliosphere and outward convection by the SW. The mechanism of the solar diurnal anisotropy was developed by Ahluwalia and Dessler (1962), Krymsky (1964), and Parker (1964) based on the anisotropic diffusion-convection modulation theory of GCR transport in the heliosphere, and further developed by Gleeson and Axford (1967, 1968).

The anisotropy vector \(A\) is expressed in terms of the stream of GCRs and spatial density gradient, as (Gleeson, 1969):

where \(N\) is the GCRs density, \(\boldsymbol{G} = \frac{\nabla N}{N}\) is the density gradient, \(\boldsymbol{S}\) is the stream of GCRs, \(K\) is the diffusion tensor representing the diffusion and drift effects of GCRs, \(V\) and \(U\) are speeds of the GCRs particles and of the SW, respectively, \(C\) is the Compton–Getting factor.

The components of the free-space anisotropy vector \(\boldsymbol{A}=[A _{r},\ A _{\theta},\ A_{\phi}]\) in spherical coordinates centered on the Sun are in the following form (Riker and Ahluwalia, 1987; Bieber and Chen, 1991; Alania et al., 2001):

where \(K_{\bot }\), \(K _{\coprod}\), and \(K _{T}\) are perpendicular, parallel and drift diffusion coefficients of GCRs, respectively; \(G_{r}^{\pm}\), \(G_{\theta }^{\pm }\) and \(G_{\phi }^{\pm }\) are the radial, heliolatitudinal and heliolongitudinal gradients of GCRs; signs (−) and (+) correspond to the HMF lines toward (negative) and away (positive) from the northern hemisphere of the Sun; \(V\) and \(U\) are speeds of the GCRs particles and of the SW, respectively; \(\Psi \) is the angle between the HMF lines and the Earth-Sun line; \(C=1.5\) for GCRs sensitive to neutron monitors (NMs) energy.

It can be seen from the system of Equations 2 – 4 that the GCR anisotropy (recorded by NMs on the Earth) must be due to diffusion, convection and drift of GCRs particles in the regular HMF of the interplanetary space. It is, on average, 0.3 – 0.4%. At the same time, the fraction of the particle drift effect can reach 0.05 – 0.1% of the average anisotropy (Alania et al., 1983, 1987, 2001; Alania, Bochorishvili, and Iskra, 2003). It is necessary to distinguish two types of the drift effect in the GCR anisotropy. The first type, due to the gradient and curvature of the HMF, can be identified in changes in the average anisotropy of GCRs in different periods of solar magnetic cycle \(qA>0\) and \(qA<0\) (for \(qA>0\), the HMF lines come out from the northern hemisphere of the Sun, and for \(qA<0\), they enter the northern hemisphere of the Sun). The second type of drift, due to the existence of local spatial gradients of the GCRs, is manifested in different sectors of the HMF. This component of drift is most notably linked to the heliospheric current sheet (HCS). The HCS is the surface where the polarity of the Sun’s magnetic field changes from south to north and vice versa. The tilt angle (TA) is referred to the latitudinal extension (or waviness) of the HCS. We suppose that this drift effect can be manifested due to the sector structure of HMF for the minima epochs of SA, when the TA of the HCS is \(<10\,\mbox{--}\,15\) degrees, i.e. the Earth is located near the weakly wavy HCS. Revealing this type of drift may be difficult due to changes in SW speed and corotating interaction region (CIR) areas when the fast SW catches up slow SW (Richardson, 2018) disrupting the stability of the HMF sector structure. The absence of a significant azimuthal gradient in GCRs density when changing the HMF sign indicates a limited HCS thickness. This thickness should be many times smaller than the Larmor radius of GCRs particles with energy range of 1 – 10 GeV. If the width of the HCS were of the order of the Larmor radius or greater, then the Earth, moving in orbit around the Sun, would pass areas with isotropic and anisotropic diffusion and we would observe a significant azimuthal GCRs density gradient (Alania and Dzhapiashvili, 1979).

However, in order to detect the first type of the drift effect in GCR anisotropy, it is possible to average data over a long period of time (for example, over a period of \(\approx 11\) years). Whilst a clear identification of the second type of the drift effect is difficult on the background of changes in SW parameters for a short period of time comparable with the durations of the positive and negative sectors of the HMF.

Investigation of the role of the drift effect in the temporal changes of the anisotropy of GCRs is very important from the point of view of the GCRs particle transport theory in the heliosphere (e.g. Siluszyk, Wawrzynczak, and Alania, 2011; Siluszyk, Iskra, and Alania, 2015). On the one hand, it allows one to understand the behavior of GCRs particles transport in the heliosphere (Kota and Jokipii, 1983, 1998; Potgieter and Moraal, 1985; Burger and Potgieter, 1989; Potgieter, 1995; Alania et al., 2001; Siluszyk et al., 2018; Siluszyk, Iskra, and Alania, 2014; Iskra, Siluszyk, and Alania, 2015; Alania, Iskra, and Siluszyk, 2010; Iskra et al., 2019). On the other hand, the clearly revealed drift effect in GCR anisotropy allows to estimate the various parameters characterizing the SW and the diffusion of GCRs (Alania, Bochorishvili, and Iskra, 2003).

Recently, Dubey, Kumar, and Dubey (2018) analyzed the GCRs diurnal phase during 1986 – 2017 and confirmed its Hale cycle dependence (\({\approx}\, 22\) years connected with solar magnetic cycle). Park et al. (2018) analyzed the diurnal variation comparing results of calculations for the pile-up method and harmonic analysis method. Oh, Yi, and Bieber (2010) found that the higher energy NMs contribute more to the 11 year phase variation of GCR anisotropy due to the diffusion process. Sabbah (2013) reported that the diurnal phase of higher energy NMs shifts towards earliest hours; this is connected with outward convection by SW, which increases the radial component of the daily variation more than the azimuthal component.

The aim of this work is to continue research on the role of the drift effect on temporary changes in GCR anisotropy. We analyze in detail the anisotropy behavior in Solar Cycle 24, especially during the solar minimum 23/24 in 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\) in comparison to the period 2017 – 2018 being near the solar minimum 24/25 when \(qA>0\). The most important issue is, based on anisotropy analysis, to determine the contribution of the drift effect in GCR modulation especially near solar minimum periods for Solar Cycle 24.

This paper is organized as follows: in Section 1 we present a short introduction and description of anisotropy of GCRs. Section 2 introduces data and methods used to calculate the GCR anisotropy. In Section 3 we present experimental results and a discussion. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2 Data and Methods

We use the hourly data of GCRs intensity for NMs with geomagnetic cut-off rigidities \(Rc<5~\mbox{GV}\). For calculation of the GCR anisotropy we follow the procedure from (Modzelewska and Alania, 2018; Ahluwalia et al., 2015). Details of the NMs and parameters used for calculations are presented in Table 1.

First for calculations of the daily radial \(A_{r}\) and tangential \(A_{\phi } \) components of the diurnal variation of the GCRs intensity for each NM, we use the harmonic analysis method (e.g. Gubbins, 2004; Wolberg, 2006):

where

where \(y_{i}\) designates the hourly GCRs intensity data, \(k\) is the consecutive harmonic of the Fourier extension. The daily radial \(A_{r}\) and tangential \(A_{\phi } \) components of the diurnal variation of the GCRs intensity were calculated by means of normalized and detrended (excluding 25 hours trend) hourly data of the pressure corrected GCRs intensity as the first (\(k=1\), \(2p=24\) hours) harmonic of the Fourier extension.

We exclude from consideration the diurnal amplitudes \(>0.7\)% as an anomalous events related to the transient disturbances in the interplanetary space, generally connected with Forbush decreases and we do not take into account HMF sectors with duration less than 4 days. The number of excluded days is less than 2 – 3% from the total number of days used for analysis.

Next, in order to find local components of diurnal variation we rotate the vector by geographic longitude \(\Lambda _{\mathrm{geo}}\) of each NM station. Furthermore, we convert the radial \(A _{r}\) and tangential \(A_{\phi }\) components of the GCRs diurnal variation into the radial \(A _{r}\) and azimuthal \(A_{\phi }\) components of the GCR anisotropy into the heliosphere (free space), (for details see Modzelewska and Alania, 2018), dividing the diurnal components by coupling coefficients (CC). The CCs represent the ratio of the diurnal variation to the corresponding amplitude of the anisotropy of cosmic rays in the heliosphere (Dorman, 1963; Yasue, Sakakibara, and Nagashima, 1982).

The calculated components of the diurnal variation of the GCRs intensity are corrected due to influence of the Earth magnetic field (Dorman et al., 1972; Dorman, 2009), taking into account the asymptotic cone of acceptance characteristic for each NM station (Shea, Smart, and Mc Cracken, 1965; Shea et al., 1967) for the rigidity to which NMs respond. The asymptotic cones of acceptance for each NM station were calculated using the FORTRAN TJ2000 program developed by Shea et al. (1967). Geomagnetic field coefficients were taken for the epoch of 2015 of the International Geomagnetic Reference Field. It is done by the rotation of the corresponding angle, called geomagnetic bending (GB), \(\varphi _{\mathrm{GB}} = \Lambda _{\mathrm{asym}} - \Lambda _{\mathrm{geo}}\) characteristic for each NM station, \(\Lambda _{\mathrm{asym}}\) and \(\Lambda _{\mathrm{geo}}\) are the asymptotic and geographic longitude. The radial and the tangential components of the diurnal variation of the GCRs intensity corrected to the Earth’s magnetic field influence are expressed (e.g. Ygbuhay, 2015):

Finally, we correct the GCR anisotropy for the Compton–Getting (CG) effect, due to the Earth’s orbital motion (Ahluwalia and Ericksen, 1970; Hall, Duldig, and Humble, 1996). The CG correction is a vector with amplitude \(0.045 \cos\lambda _{\mathrm{asym}}\) and phase 6 h, where \(\lambda _{\mathrm{asym}}\) is the asymptotic latitude of each NM.

The GCRs intensity measured by ground-based NMs is based on the concept of an integrated GCR flux above the magnetic rigidity threshold that depends on the geomagnetic cut-off typical for each NM. In this case there arises the question of what the real energy is of the measurement. It is natural to introduce the “effective energy/rigidity” typical for a GCR detector, here NM. In the literature this term has different meanings: fixed energy/rigidity \({\approx}\, 10~\mbox{GV}\) for a NM, (Belov, 2000), median energy (Ahluwalia and Dorman, 1997; Jämsén et al., 2007), maximum of the differential response function (McCracken et al., 2004), or the integral effective energy (Alanko et al., 2003). Unfortunately the above-mentioned effective energy concepts are not constant but are changing through the solar activity cycle. Recently, Gil et al. (2017) proposed a model of the effective energy in which the variability of the GCR flux at this energy is directly proportional to the detector’s count rate, so that the percentage variability of the detector’s count rate is equal to that of the GCR flux at this energy; for details see Asvestari et al. (2017).

In this paper we compare the analysis of the GCR anisotropy using this two approaches: the median rigidity \(R _{\mathrm{m}}\) of NM response (Ahluwalia et al., 2015; Ahluwalia and Fikani, 2007) and the effective rigidity \(R_{\text{ef}}\) characteristic for each NM proposed by (Gil et al., 2017; Asvestari et al., 2017).

3 Experimental Results and Discussion

Solar Cycle 24 was much less active than, for example, Solar Cycle 23, being rather similar to cycles at the beginning of the previous century. During this relatively weak cycle not many impulsive events happened on the Sun, but we could observe the prolonged solar minimum 23/24 with good established regular structure of the HMF. The current Solar Cycle 24 has now more or less finished its descending phase. At the beginning of 2018 (≈ April), the Sun showed indications of the reverse magnetic polarity sunspot announcing Solar Cycle 25 (Phillips, 2018). The poleward reversed polarity sunspots suggest that a transition to Solar Cycle 25 is in progress and indicates that we may be in or near the minimum between Solar Cycles 24 and 25. So it is of special importance to study the features of the GCR anisotropy characteristics through the almost whole Solar Cycle 24 with special importance because of the comparison of the drift effect in GCR anisotropy during solar minimum 23/24 and near the solar minimum 24/25 with different polarity periods of solar magnetic cycle.

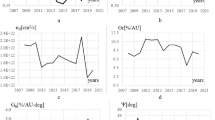

Here we present the time variation of the GCR anisotropy for Oulu NM (as an example) through almost the whole Solar Cycle 24, 2007 – 2018. We compare the values of the amplitude, phase, radial and azimuthal components of the GCR anisotropy using two approaches: median \(R _{\mathrm{m}}\) (Ahluwalia et al., 2015) and effective \(R_{\text{ef}}\) (Gil et al., 2017) rigidity of response. The errors for annual values are estimated as the standard deviation from monthly data. The calculated results of the GCR anisotropy for effective and median rigidity are in good agreement, the difference is in the scope of the error bars. Figure 1 presents the time lines of the annual average of the amplitude (Figure 1a), phase (Figure 1b), radial (Figure 1c) and azimuthal (Figure 1d) components of the GCR anisotropy for 2007 – 2018. The amplitude of the GCR anisotropy displays the 11-year variation with systematic decrease of the values near the minima of SA (Figure 1a). The phase of the GCR anisotropy shows the undoubted indication of shifting towards earlier hours near the solar minimum 24/25 (Figure 1b). Figure 1c demonstrates the change of the \(A _{r}\) component from positive to negative values close the maximum of the solar cycle nearby to the reversal of the global HMF.

As far the differences of the GCR anisotropy parameters calculated for these two approaches: median and effective rigidity are rather negligible, we decided to use further in this paper only the GCR anisotropy using a recent \(R_{\mathrm{ef}}\) methodology following Gil et al. (2017).

The aim of this work is to continue research on the role of the drift effect on temporary changes in GCR anisotropy. The most important issue is, based on the anisotropy analysis, to determine the contribution of the drift effect in the GCR modulation especially near solar minimum periods for Solar Cycle 24. For this purpose components \(A _{r}\) and \(A_{\phi }\) of the anisotropy of GCRs were calculated using the harmonic analyses of hourly data of every separate NM for periods of two minima: solar minimum 23/24: 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\) and near solar minimum 24/25: 2017 – 2018, when \(qA>0\).

In Figures 2a, b, c are presented average GCR anisotropy vectors from following NMs: Apatity, Oulu, Newark, Thule, Fort Smith, Inuvik, Kerguelen, Terre Adelie and Nain (see Table 1) for different sectors of the HMF (‘+’ corresponds to the positive and ‘−’ to the negative sectors) for the solar minimum 23/24 when \(qA<0\): 2007 (Figure 2a), 2008 (Figure 2b), and 2009 (Figure 2c). In 2007 data for Terre Adelie and Kerguelen NMs and in 2008 for Terre Adelie NM are not available.

In Figures 3a, b are presented average vectors of the GCR anisotropy for different sectors of the HMF for the period near the solar minimum 24/25 when \(qA>0\): 2017 (Figure 3a) and 2018 (Figure 3b). Here we used data of the same NMs as in Figure 2.

The same as in Figure 2 but near solar minimum 24/25 when \(qA>0\): 2017 (a) and 2018 (b).

Table 2 presents the radial and azimuthal components, magnitude of the GCR anisotropy and the phase relative to 18 h. The uncertainty of this data is estimated as the Poisson statistics using standard deviations for separate NMs divided by \(\sqrt{n}\), where \(n\) is the number of NMs used in averaging for each period. As far as the drift stream is evidently pronounced in the radial component we present in Table 2 also the ratios of the absolute value of the radial component to the value of the magnitude of the GCR anisotropy vector. All quantities are for the different HMF sectors in 2007, 2008, 2009 and averaged values for 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\) and the same in 2017, 2018 and averaged for the period 2017 – 2018, when \(qA>0\).

From Figures 2a, b, c and Table 2, we can see that all vectors of the GCR anisotropy for both positive and negative sectors of HMF are slightly shifted towards later hours in relation to 18 hour for 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\). In 2007 the shifting is 24 min for the positive sectors and 3 min for the negative sectors, in 2008 – 14 min and 5 min all after 18 h, respectively. These values are very small and are in the scope of the error bars. In 2007 and 2008 the vectors of the GCR anisotropy for the positive sectors are shifted towards the later hours than the vector for the negative sectors. The ratios of the absolute value of the radial component to the value of the total anisotropy vector are \(10.6\pm 1.1\)% and \(1.3\pm 0.8\)% in 2007 for positive and negative sectors and \(6.0\pm 1.1\)% and \(2.3\pm 1.2\)% in 2008, respectively.

There is an unusual behavior of the vector of the GCR anisotropy in 2009. The vector of the GCR anisotropy for the positive sectors practically points to 18 hours (phase + 2 min before 18 h, phase – 2 min after 18 h). In 2009 the radial components of the anisotropy vectors for different sectors are almost zero (\(A _{r} +\) is \(-0.003\pm 0.004\)% towards 12 h and \(A _{r} -\) is \(0.003\pm 0.004\)% towards 24 h). The ratios of the absolute value of the radial component to the value of the total anisotropy vector in 2009 are \(0.8\pm 1.3\)% and \(1.0\pm 1.3\)% for positive and negative sectors, respectively. These quantities are practically the same within the error limits.

This means that in the above periods diffusion is responsible for the propagation of cosmic radiation in the heliosphere, while the drift of cosmic-ray particles due to the gradient and curvature is insignificant and in 2009 it hardly existed. One can see also that there are small differences between the amplitudes and phases of the GCR anisotropy vectors for different sectors of the HMF in 2008 and 2009. Moreover, the effect of drift in the anisotropy of GCRs due to the sector structure of the HMF during the minima epochs of SA is generally caused by the drift on the HCS and is mostly pronounced in the differences of azimuthal components between positive and negative sectors in 2007.

From Figures 3a, b and Table 2 one can see that all vectors of the GCR anisotropy for both positive and negative sectors of HMF are shifted towards earlier hours compared to 18 hour in 2017 – 2018, when \(qA>0\). In 2017 (Figure 3a) the magnitude of the vector of the GCR anisotropy for the negative sector of HMF is less (\(A-=0.365\pm 0.005\)%) than the magnitude of the vector for the positive sector (\(A+=0.429\pm 0.004\)%). We have the reverse situation in 2018 (Figure 3b) (\(A+=0.324\pm 0.005\)%), is less than (\(A-=0.379\pm 0.005\)%). The anisotropy vector for the negative sector is shifted towards the later hours in 2017, at the same time we observe no significant difference in the phase for both sectors in 2018. The ratios of the absolute value of the radial component to the value of the total anisotropy vector are \(33.8 \pm 0.9\)% and \(25.8\pm 1.7\)% in 2017 and in 2018 the ratios are even higher, being \(56.3\pm 1.1\)% and \(57.5\pm 0.6\)% for the positive and negative sectors, respectively. The ratios for various sectors in 2018 are practically the same within the error bars. The effect of drift in the anisotropy of GCRs due to the sector structure of the HMF is most pronounced in the differences of azimuthal components between positive and negative sectors in 2017 and 2018.

Figure 4a and Table 2 show the average GCR anisotropy vectors for different sectors of the HMF averaged over the periods 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\) and 2017 – 2018, when \(qA>0\). One can see that in 2007 – 2009 the magnitude of the vector for positive (+) sectors of HMF is a bit less (\(A+=0.411\pm 0.004\)%) than the magnitude of the vector for the negative sectors (\(A-=0.442\pm 0.004\)%). Phases of the vectors \(A+\) and \(A-\) are directed 13 min and 4 min, respectively, after 18 h in 2007 – 2009. Whereas in 2017 – 2018 there is no noticeable difference between positive and negative sectors; the magnitude of the anisotropy vectors is \(\approx 0.37\)% for both sectors, and the phase is shifted \(\approx 1\):40 h before 18 h. The ratios of the absolute value of the radial component to the value of the total anisotropy vector are for the whole solar minimum 23/24 in 2007 – 2009 when \(qA<0\): \(5.8\pm 2.0\)% and \(1.5\pm 1.3\)% for (+) and (−) sectors, respectively and near the solar minimum 24/25 in 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\) the ratios are \(43.8\pm 0.4\)% and \(42.6\pm 3.7\)% for (+) and (−) sectors, respectively and practically are the same within the error bars.

(a) Harmonic diagram of the average GCR anisotropy for positive (+) and negative (−) sectors of HMF for the periods 2007 – 2009 when \(qA<0\) and 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\); (b) harmonic diagram of the average over sectors the GCR anisotropy for 2007 – 2009 when \(qA<0\) and 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\) for the global HMF.

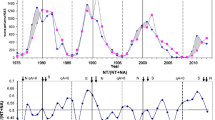

Having calculated anisotropy vectors for different sectors, we average the vectors of the GCR anisotropy over different sectors but for the same directions of the global HMF. Figure 4b and Table 3 show, averaged over HMF sectors, the anisotropy vectors for different directions of the global HMF i.e. for 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\) and 2017 – 2018, when \(qA>0\).

Summarizing, in the solar minimum 23/24 in 2007 – 2009 when \(qA<0\), the drift effect is not pronounced visibly in the changes of the \(A_{r}\) component being almost 0 (\(A_{r}=0.02 \pm 0.04\)%), determining the phase shifted 14 min after 18 h, i.e. for this solar minimum the diffusion dominated model of GCR transport is more acceptable in 2007 – 2009. In turn, near the solar minimum 24/25 in 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\), the radial component \(A _{r}\) is \(-0.16 \pm 0.05\)% and the phase is shifted 1:09 h prior 18 h. So, the drift effect is clearly visible. So in the period of 2017 – 2018 the diffusion model with clearly manifest drift is acceptable. For the whole solar minimum 23/24 in 2007 – 2009 when \(qA<0\) the ratio of the absolute value of the radial component to the value of the total anisotropy vector is \(3.6\pm 2.4\)%, whereas near the solar minimum 24/25 in 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\) this ratio is \(43.3\pm 11.6\)%.

In Figure 5 are presented the average vector of the GCR anisotropy \(\boldsymbol{A}_{\mathrm{av}}^{qA < 0}\) for 2007 – 2009, \(\boldsymbol{A}_{\mathrm{av}}^{qA > 0}\) for 2017 – 2018 and \(A_{\mathrm{av}}\) for almost the whole Solar Cycle 24 in 2007 – 2018 (dashed line). Figure 5 also presents the drift vectors \(A_{\text{dr}}\) for \(qA<0\) (blue) calculated as (\(\boldsymbol{A}_{\mathrm{av}}^{qA < 0} - A_{\text{av}}\)) and \(A_{\text{dr}}\) for \(qA>0\) (red) calculated as (\(\boldsymbol{A} _{\mathrm{av}}^{qA > 0} - A_{\text{av}}\)).

Harmonic diagram of the average vector of the GCR anisotropy \(\boldsymbol{A}_{\mathrm{av}}^{qA < 0}\) for 2007 – 2009, \(\boldsymbol{A}_{\mathrm{av}}^{qA > 0}\) for 2017 – 2018 and \(A_{\mathrm{av}}\) for the almost whole Solar Cycle 24 in 2007 – 2018 (dashed line). Figure 5 presents the drift anisotropy vectors \(\boldsymbol{A}_{\text{dr}}\) for \(qA<0\) (blue) and \(\boldsymbol{A}_{\text{dr}}\) for \(qA >0\) (red).

One can see that the drift anisotropy vector \(A_{\text{dr}}\) (red color in Figure 5) for the \(qA>0\) polarity is preferentially directed to the Sun (to the direction of 12 h in the harmonic diagram), and for the \(qA<0\) polarity the drift anisotropy vector \(\boldsymbol{A}_{\text{dr}}\) (blue color in Figure 5) is directed out of the Sun. These empirical outcome are in good correspondence with the drift theory of modulation of GCRs (Jokipii, Levy, and Hubbard, 1977). Based on that theory in the \(qA>0\) cycle a drift stream of GCRs caused by the gradient and curvature of the HMF is preferentially coming from the polar regions to the helioequatorial region and is directed away from the Sun. For the \(qA<0\) cycle we have the opposite direction of the drift stream of GCRs.

Table 4 presents the radial and azimuthal components and magnitude of the drift GCR anisotropy vector \(A_{\text{dr}}\) and the ratios of the absolute value of the \(A ^{r}_{\text{dr}}\) and \(A ^{\phi}_{\text{dr}}\) components to the total magnitude of \(A_{\text{dr}}\) for 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\) and 2017 – 2018, when \(qA>0\). In the solar minimum 23/24 in 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\), the ratio \(A_{\mathrm{dr}}^{r}/A_{\mathrm{dr}}\) is \({\approx}\, 99\)%. In turn, near the solar minimum 24/25 in 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\), the ratio \(A_{\mathrm{dr}}^{r}/A_{\mathrm{dr}}\) reaches \({\approx}\, 86\)%.

Thus, the drift vectors \(A_{\text{dr}}\) of the GCR anisotropy (Figure 5) for \(qA>0\) and \(qA<0\) polarities basically contain the radial component, the contribution of \(A_{\mathrm{dr}}^{r}\) in total \(A_{\mathrm{dr}}\) is more than \({\approx}\, 86\)% for \(qA>0\) and almost \({\approx}\, 99\)% in \(qA<0\). The difference between anisotropy \(A\) for \(qA>0\) and \(qA<0\) polarities is produced by the drift of GCRs due to the curvature and gradient of the regular HMF and is the source of the long-term variation of the anisotropy \(A\) of GCRs (Forbush, 1969; Ahluwalia, 1988).

Summarizing, in the solar minimum 23/24 in 2007 – 2009, when \(qA<0\), the drift effect is not pronounced visibly, the ratio \(\vert A_{r} \vert /A _{\mathrm{av}}\) is only \(\approx 4\)%. Hence the diffusion dominated model of GCR transport is more acceptable in 2007 – 2009. In turn, near the solar minimum 24/25 in 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\), the drift effect is clearly visible and the ratio \(\vert A_{r} \vert /A_{\mathrm{av}}\) reaches \(\approx 40\)%. So in the period of 2017 – 2018 the diffusion model with clearly manifest drift is acceptable. The above-mentioned statements are in agreement with other authors. According to (Moraal and Stoker, 2010; Mewaldt et al., 2010) the solar minimum 23/24 was diffusion dominated with increasing of diffusion coefficient of GCRs particles in comparison to the previous solar minimum and consequently the drift effect was reduced. In 2007 – 2008 tilt angle was relatively large (\(\approx 30^{\circ}\)), so the drift effect might be reduced (maybe because of the weak HMF), consequently the latitudinal gradient is also smaller. At the same time coronal holes, CIRs and SW velocity were stable, so convection was strong. Due to the weak HMF diffusion was also enhanced. However, many characteristics of the heliospheric environment were not typical compared with earlier Solar Cycles, e.g. lower SW dynamic pressure and magnetic field strength, but high TA, together resulting in the extremely high GCRs intensities in 2009. Comparing Solar Cycles 23 and 24 it was observed (Dunzlaff et al., 2008) lower effectiveness of the latitudinal transport in 2006 – 2009. Also (De Simone et al., 2011) reported smaller negative latitudinal gradient in the \(qA<0\) polarity in Solar Cycle 24 comparing to previous \(qA<0\), but TA was rather high (e.g. Heber et al., 2009), so the GCR modulation processes in the solar minimum 23/24, when \(qA<0\) maybe a consequence of large latitudinal extent of HCS (Potgieter and Ferreira, 2001; Heber et al., 2009).

The results presented in this paper will be used in future work concerning the modeling of the transport of GCRs particles as the crucial parameters characterizing the solar modulation of GCRs by the SW in the heliosphere.

4 Conclusions

Using data from several neutron monitor stations of different magnetic rigidity cut-offs, we have studied the role of drift in the temporal variations of the GCR anisotropy and its influence on the sector structure of the heliospheric magnetic field. Using the harmonic analysis method, we have analyzed the GCR anisotropy in the \(qA<0\) solar minimum period of 2007 – 2009 (Cycle 23/24) and near the \(qA>0\) minimum period of 2017 – 2018 (Cycle 24/25). Our main results can be summarized as follows:

- i)

We have compared the analysis of the GCR anisotropy using the median \(R _{\mathrm{m}}\) and effective \(R_{\text{ef}}\) rigidity of neutron monitor response. We have found that the differences of the GCR anisotropy parameters calculated for these two approaches: median and effective rigidity are rather negligible.

- ii)

The global drift due to gradient and curvature of the heliospheric magnetic field is manifested in the radial component \(A _{r}\) of the anisotropy \(A\) of GCRs. For the \(qA<0\) cycle the \(A _{r}\) is directed away from the Sun, but for the \(qA>0\) magnetic cycle the \(A _{r}\) is directed to the Sun. This type of the drift effect is the source of the 22-year variation of the anisotropy of GCRs.

- iii)

The drift effect due to the sector structure of the heliospheric magnetic field in the anisotropy \(A\) of GCRs (during the minima epochs of solar activity) is caused by the heliospheric current sheet and is visible in the azimuthal component of GCR anisotropy.

- iv)

We have shown that in the solar minimum 23/24 in 2007 – 2009 when \(qA <0\), the drift effect is not pronounced visibly in the changes of the \(A_{r}\) component (\(A_{r} \approx 0\)), i.e. for this solar minimum the drift effect is only \({\approx}\, 4\)%. Hence the diffusion dominated model of GCR transport is more acceptable in 2007 – 2009. In turn, near the solar minimum 24/25 in 2017 – 2018 when \(qA>0\), the drift effect is clearly visible and reaches \({\approx}\, 40\)%. So in the period of 2017 – 2018 the diffusion model with clearly manifest drift is acceptable.

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Abbreviations

- CC:

-

Coupling coefficients

- CG:

-

Compton–Getting effect

- CIR:

-

Corotating Interaction Regions

- GCRs:

-

Galactic Cosmic Rays

- HCS:

-

Heliospheric Current Sheet

- HMF:

-

Heliospheric Magnetic Field

- NM:

-

Neutron Monitor

- SA:

-

Solar Activity

- SW:

-

Solar Wind

- TA:

-

Tilt Angle.

References

Ahluwalia, H.S.: 1988, The regimes of the east–west and the radial anisotropies of cosmic rays in the heliosphere. Planet. Space Sci.36(12), 1451. DOI . ADS .

Ahluwalia, H.S., Dessler, A.J.: 1962, Diurnal variation of cosmic radiation intensity produced by a solar wind. Planet. Space Sci.9(5), 195 DOI .

Ahluwalia, H.S., Dorman, L.I.: 1997, Transverse cosmic ray gradients in the heliosphere and the solar diurnal anisotropy. J. Geophys. Res.102(A8), 17433. DOI . ADS .

Ahluwalia, H.S., Ericksen, J.H.: 1970, Solar diurnal variations of cosmic ray intensity underground during solar activity Cycle-20. Acta Phys. Acad. Sci. Hung.29(Suppl. 2), 139. ADS .

Ahluwalia, H.S., Fikani, M.M.: 2007, Cosmic ray detector response to transient solar modulation: Forbush decreases. J. Geophys. Res.112(A8), A08105 DOI . ADS .

Ahluwalia, H.S., Ygbuhay, R.C., Modzelewska, R., Dorman, L.I., Alania, M.V.: 2015, Cosmic ray heliospheric transport study with neutron monitor data. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys.120(10), 8229. DOI . ADS .

Alania, M.V., Bochorishvili, T.V., Iskra, K.: 2003, Effects of the sector structure of the interplanetary magnetic field on galactic cosmic ray anisotropy. Solar Syst. Res.37(6), 519. DOI . ADS .

Alania, M.V., Dzhapiashvili, T.V.: 1979, The expected features of cosmic ray anisotropy due to hall-type diffusion and the comparison with the experiment. In: Proc. 16th ICRC, Kyoto, Japan, 3, 19. ADS .

Alania, M.V., Iskra, K., Siluszyk, M.: 2010, On relation of the long period galactic cosmic rays intensity variations with the interplanetary magnetic field turbulence. Adv. Space Res.45(10), 1203. DOI .

Alania, M.V., Babaian, V.Kh., Belov, A.V., Gushchina, R.T., Dorman, L.I., Eroshenko, E., Oleneva, V.A.: 1983, Interplanetary modulation of the anisotropy and density of cosmic rays. In: Izvestiia47, 1864. ADS .

Alania, M.V., Aslamazashvili, R.G., Bochorishvili, T.B., Despotashvili, M.A., Djapiashvili, T.V., Gachechiladze, G.R.: 1987, The experimental and theoretical investigations of the of the regular IMF influence on the spatial distribution of cosmic ray density and anisotropy. In: Proc. 20th ICRC, Moscow, Russia, 4, 79. ADS .

Alania, M.V., Aslamazashvili, R.G., Bochorishvili, T.B., Iskra, K., Siluszyk, M.: 2001, The role of drift on the diurnal anisotropy and on temporal changes in the energy spectra of the 11-year variation for galactic cosmic rays. Adv. Space Res.27(3), 613. DOI .

Alanko, K., Usoskin, I.G., Mursula, K., Kovaltsov, G.A.: 2003, Heliospheric modulation strength: effective neutron monitor energy. Adv. Space Res.32(4), 615. DOI . ADS .

Asvestari, E., Gil, A., Kovaltsov, G.A., Usoskin, I.G.: 2017, Neutron monitors and cosmogenic isotopes as cosmic ray energy-integration detectors: effective yield functions, effective energy, and its dependence on the local interstellar spectrum. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys.122, 9790. DOI . ADS .

Bazilevskaya, G., Broomhall, A.M., Elsworth, Y., Nakariakov, V.M.: 2014, A combined analysis of the observational aspects of the quasi-biennial oscillation in solar magnetic activity. Space Sci. Rev.186(1–4), 359. DOI . ADS .

Belov, A.: 2000, Large scale modulation: view from the Earth. Space Sci. Rev.93(1/2), 79. DOI . ADS .

Bieber, J.W., Chen, J.: 1991, Cosmic-ray diurnal anisotropy, 1936 – 1988: implications for drift and modulation theories. Astrophys. J.372, 301. DOI . ADS .

Burger, R.A., Potgieter, M.S.: 1989, The calculation of neutral sheet drift in two-dimensional cosmic-ray modulation models. Astrophys. J.339, 501. DOI . ADS .

Chowdhury, P., Kudela, K., Moon, Y.J.: 2016, A study of heliospheric modulation and periodicities of galactic cosmic rays during Cycle 24. Solar Phys.291(2), 581. DOI . ADS .

De Simone, N., Di Felice, V., Gieseler, J., Boezio, M., Casolino, M., Picozza, P., Heber, B. (PAMELA Collaboration): 2011, Latitudinal and radial gradients of galactic cosmic ray protons in the inner heliosphere – PAMELA and Ulysses observations. Astrophys. Space Sci. Trans.7(3), 425. DOI . ADS .

Dorman, L.I.: 1963, Variations of Cosmic Rays and Space Exploration, AN SSSR, Moscow.

Dorman, L.I.: 2009, Cosmic Rays in Magnetospheres of the Earth and Other Planets, Astrophys. Space Sci. Lib.358, Springer, Berlin.

Dorman, L.I., Gushchina, R.T., Smart, D.F., Shea, M.A.: 1972, Effective Cut-Off Rigidities of Cosmic Rays, Nauka, Moscow.

Dubey, A., Kumar, S., Dubey, S.K.: 2018, Variation in diurnal phase of cosmic ray intensity during 1986 – 2017. Res. Rev. J. Phys.7(3), 20. http://sciencejournals.stmjournals.in/index.php/RRJoPHY/article/view/1227 .

Dunzlaff, P., Heber, B., Kopp, A., Rother, O., Mueller-Mellin, R., Klassen, A., et al.: 2008, Observations of recurrent cosmic ray decreases during Solar Cycles 22 and 23. Ann. Geophys.26(10), 3127. DOI . ADS .

Forbush, S.E.: 1969, Variation with a period of two solar cycles in the cosmic-ray diurnal anisotropy and the superposed variations correlated with magnetic activity. J. Geophys. Res.74(14), 3451. DOI . ADS .

Gil, A., Asvestari, E., Kovaltsov, G.A., Usoskin, I.: 2017, Heliospheric modulation of galactic cosmic rays: effective energy of ground-based detectors. In: Proc. 35th ICRC, Busan, Korea, Proc. of Sci.301, 32.

Gleeson, L.J.: 1969, The equations describing the cosmic-ray gas in the interplanetary region. Planet. Space Sci.17(1), 31. DOI . ADS .

Gleeson, L.J., Axford, W.I.: 1967, Cosmic rays in the interplanetary medium. Astrophys. J.149, L115. DOI . ADS .

Gleeson, L.J., Axford, W.I.: 1968, Solar modulation of galactic cosmic rays. Astrophys. J.154, 1011. DOI . ADS .

Gubbins, D.: 2004, Time Series Analysis and Inverse Theory for Geophysicists, Cambridge University Press Cambridge

Hall, D.L., Duldig, M.L., Humble, J.E.: 1996, Analyses of sidereal and solar anisotropies in cosmic rays. Space Sci. Rev.78(3–4), 401. DOI . ADS .

Heber, B., Kopp, A., Gieseler, J., Muller-Mellin, R., Fichtner, H., Scherer, K., Potgieter, M.S., Ferreira, S.E.S.: 2009, Modulation of galactic cosmic ray protons and electrons during an unusual solar minimum. Astrophys. J.699(2), 1956. DOI . ADS .

Iskra, K., Siluszyk, M., Alania, M.V.: 2015, Rigidity spectrum of the long-period variations of the galactic cosmic ray intensity in different epochs of solar activity. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.632, 012079. DOI .

Iskra, K., Siluszyk, M., Alania, M.V., Wozniak, W.: 2019, Solar physics, experimental investigation of delay time in galactic cosmic rays flux in different epochs of solar magnetic cycles: 1959 – 2014. Solar Phys.294, 115. DOI . ADS .

Jämsén, T., Usoskin, I.G., Räihä, T., Sarkamo, J., Kovaltsov, G.A.: 2007, Case study of forbush decreases: energy dependence of the recovery. Adv. Space Res.40(3), 342. DOI . ADS .

Jokipii, J.R., Levy, E.H., Hubbard, W.B.: 1977, Effects of particle drift on cosmic-ray transport. I. General properties, application to solar modulation. Astrophys. J.213, 861. DOI . ADS .

Kota, J., Jokipii, J.R.: 1983, Effects of drift on the transport of cosmic rays. VI – A three-dimensional model including diffusion. Astrophys. J.265, 573. DOI . ADS .

Kota, J., Jokipii, J.R.: 1998, Modeling of 3-D corotating cosmic-ray structures in the heliosphere. Space Sci. Rev.83(1/2), 137. ADS .

Krymsky, G.F.: 1964, Geomagn. Aeron.4, 763.

Kudela, K., Sabbah, I.: 2016, Quasi-periodic variations of low energy cosmic rays. Sci. China, Technol. Sci.59(4), 547. DOI .

McCracken, K., McDonald, F., Beer, J., Raisbeck, G., Yiou, F.: 2004, A phenomenological study of the long-term cosmic ray modulation, 850-1958 AD. J. Geophys. Res.109(A12), A12103. DOI . ADS .

Mewaldt, R.A., Davis, A.J., Lave, K.A., Leske, R.A., Stone, E.C., Wiedenbeck, M.E., et al.: 2010, Record-setting cosmic-ray intensities in 2009 and 2010. Astrophys. J. Lett.723(1), L1. DOI . ADS .

Modzelewska, R., Alania, M.V.: 2018, Quasi-periodic changes in the 3D solar anisotropy of Galactic cosmic rays for 1965 – 2014. Astron. Astrophys.609, A32. DOI . ADS .

Moraal, H., Stoker, P.H.: 2010, Long-term neutron monitor observations and the 2009 cosmic ray maximum. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys.115(A12), A12109. DOI . ADS .

Oh, S.Y., Yi, Y., Bieber, J.W.: 2010, Modulation cycles of galactic cosmic ray diurnal anisotropy variation. Solar Phys.262(1), 199. DOI . ADS .

Park, E.H., Jung, J., Oh, S., Evenson, P.: 2018, Solar cyclic modulation of diurnal variation in cosmic ray intensity. J. Astron. Space Sci.35, 219. DOI . ADS .

Parker, E.N.: 1964, Theory of streaming of cosmic rays and the diurnal variation. Planet. Space Sci.12(8), 735. DOI . ADS .

Phillips, T.: 2018, A sunspot from the next solar cycle. SpaceWeather.com . Retrieved, November 20, 2018.

Potgieter, M.S.: 1995, The time-dependent transport of cosmic rays in the heliosphere. Astrophys. Space Sci.230(1–2), 393. DOI . ADS .

Potgieter, M.S., Ferreira, S.E.S.: 2001, Modulation of cosmic rays in the heliosphere over 11 and 22 year cycles: a modelling perspective. Adv. Space Res.27(3), 481. DOI . ADS .

Potgieter, M.S., Moraal, H.: 1985, A drift model for the modulation of galactic cosmic rays. Astrophys. J.294, 425. DOI . ADS .

Richardson, I.G.: 2018, Solar wind stream interaction regions throughout the heliosphere. Living Rev. Solar Phys.15, 1. DOI . ADS .

Riker, J.F., Ahluwalia, H.S.: 1987, A survey of the cosmic ray diurnal variation during 1973 – 1979 – II. Application of diffusion-convection model to diurnal anisotropy data. Planet. Space Sci.35(9), 1117. DOI . ADS .

Sabbah, I.: 2013, Solar magnetic polarity dependency of the cosmic ray diurnal variation. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys.118(8), 4739. DOI . ADS .

Shea, M.A., Smart, D.F., Mc Cracken, K.G.: 1965, A study of vertical cutoff rigidities using sixth degree simulations of the geomagnetic field. J. Geophys. Res.70(17), 4117. DOI . ADS .

Shea, M.A., Smart, D.F., Mc Cracken, K.G., Rao, U.R.: 1967, Asymptotic directions, variational coefficients and cutoff rigidities, supplement to IQSY instruction manual No. 10 cosmic ray tables. In: Office of Aerospace Research United States of Air Force.

Siluszyk, M., Iskra, K., Alania, M.V.: 2014, Rigidity dependence of the long period variations of galactic cosmic ray intensity: a relation with the interplanetary magnetic field turbulence for 1968–2002. Solar Phys.289(11), 4297. DOI . ADS .

Siluszyk, M., Iskra, K., Alania, M.V.: 2015, 2-D modelling of long period variations of galactic cosmic ray intensity. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.632, 012080. DOI .

Siluszyk, M., Wawrzynczak, A., Alania, M.V.: 2011, A model of the long period galactic cosmic ray variations. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys.73(13), 1923. DOI . ADS .

Siluszyk, M., Iskra, K., Alania, M.V., Miernicki, S.: 2018, Interplanetary magnetic field turbulence and rigidity spectrum of the galactic cosmic rays intensity variation (1968 – 2012). J. Geophys. Res.123(1), 30. DOI .

Wolberg, J.: 2006, Data Analysis Using the Method of Least Squares, Springer, Berlin.

Yasue, S., Sakakibara, S., Nagashima, K.: 1982, Coupling coefficients of cosmic rays daily variations for neutron monitors. Nagoya Report. 7.

Ygbuhay, R.C.: 2015, Galactic Cosmic Ray Transport in the Heliosphere: 1963 – 2013. PhD dissertation, The University of New, Mexico, Albuquerque, US.

Acknowledgements

Neutron monitor count rates are from the Neutron Monitor Data Base: http://www01.nmdb.eu/.

The asymptotic cones of acceptance for each NM station were calculated using the FORTRAN TJ2000 program available at http://ccmc.gsfc.nasa.gov/modelweb/sun/cutoff.html.

Geomagnetic field coefficients were taken from http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/IAGA/vmod/igrf.html.

R.M. acknowledges the financial support by the Polish National Science Centre, grant number: 2017/01/X/ST9/01023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Modzelewska, R., Iskra, K., Wozniak, W. et al. Features of the Galactic Cosmic Ray Anisotropy in Solar Cycle 24 and Solar Minima 23/24 and 24/25. Sol Phys 294, 148 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-019-1540-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-019-1540-5