Abstract

We explored the relationship between parenting practices and the experience of subjective authenticity in the parenting role. Based on work showing that authenticity responds to violations of broad social expectations, we predicted that mothers would feel more authentic than fathers. We also predicted, however, that parenting practices that conflicted with broad gender norms would differentially predict authenticity for mothers and fathers. We tested this prediction in a single study of U.S. parents recruited from an internet research panel service (N = 529). Parents completed online measures of authenticity and parenting practices on three separate occasions. We assessed the within-person association between parenting practices and parent-role authenticity. Authoritarian parenting practices negatively predicted parent-role authenticity for mothers, whereas permissive practices negatively predicted parent-role authenticity for fathers. Authoritative practices positively predicted authenticity regardless of parent gender, and, overall, women felt more authentic in the parenting role than men. These findings contribute to emerging theoretical perspectives on authenticity and gender role congruence and highlight how different parenting practices relate to the well-being of mothers and fathers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Being a parent is a psychologically consequential role. Parenthood is, among other things, associated with shifts in well-being (Nelson et al., 2014), changes in marital relationship quality (Twenge et al., 2003), and the attainment of career outcomes (Angelov et al., 2016). Many of the correlates of parenthood, however, are not uniformly experienced by men and women (Angelov et al., 2016; Morgan et al., 2021; Nelson-Coffey et al., 2019). In academia, for example, the impact of being a parent on work productivity is significantly larger for women relative to men (Morgan et al., 2021). Women also tend to identify more strongly with the role of mother than men do with the role of father, and there is greater congruence between gender and parental role norms for women, relative to men (Park & Banchefsky, 2019). This indicates that, while being a parent is no doubt consequential for both mothers and fathers, the lived experience of being a parent may differ noticeably between moms and dads.

In the current research, we considered how parents’ experience of subjective authenticity in the role of parent might relate to parenting practices (Baumrind, 1971). Feeling authentic reflects a sense of being and knowing who one “truly” is (Kernis & Goldman, 2006; Sedikides et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2008), and it robustly relates to indices of well-being (Rivera et al., 2019). Feelings of authenticity in one’s parenting role should therefore reflect a sense of being and expressing one’s true self in that role. Although a thorough understanding of authenticity is still emerging (Baumeister, 2019), some theory and research indicates that gender differences in social role expectations and goal orientations may connect to gender differences in role-specific experiences of authenticity (Dormanen et al., 2020; Schmader & Sedikides, 2018). We build on this earlier work to examine how engaging in certain kinds of parenting behaviors may relate to authenticity differently for mothers and fathers. Addressing that question may therefore inform the ways in which parenting relates to personal well-being and psychological flourishing.

Subjective Authenticity

Feeling authentic is a central aspect of psychological health and well-being (Rivera et al., 2019; Sutton, 2020). People who feel greater authenticity in their roles and day-to-day lives, for example, report lower levels of stress and greater levels of vitality (van den Bosch & Taris, 2014; Wood et al., 2008). Subjective authenticity exists as both a trait (Kernis & Goldman, 2006; Wood et al., 2008) and a state (Lenton et al., 2016; Sedikides et al., 2019), and can be assessed as a specific subjective experience tethered to a particular context or role (e.g., felt authenticity as a voter; Maffly-Kipp et al., 2022). The experience of authenticity is necessarily subjective and need not reflect an accurate understanding of one’s self (Vess, 2019) or an objective congruence between self-perception and behavior (Cooper et al., 2018). Rather, it seems to reflect an experiential feeling that is responsive to several different kinds of internal and environmental cues. Feelings of authenticity respond, for example, to shifts in positive affect (Lenton et al., 2013) and perceptions of one’s own moral goodness (Christy et al., 2016), and authenticity tends to covary with the expression of generally desirable characteristics, irrespective of how well those expressions align with self-perceived personality (Fleeson & Wilt, 2010). These latter patterns might seem counterintuitive, given that authenticity is typically conceived as an alignment of behavior with one’s true self, but the research strongly suggests that authenticity is a subjective experience that is distinct from an objective consistency or congruence between actions and explicitly endorsed traits.

The emerging authenticity literature also indicates that gender differences in authenticity may emerge in certain contexts. The “state-authenticity-as-fit-to-environment” model (Schmader & Sedikides, 2018) suggests that contexts or roles that constrain self-expression and the fluent pursuit of personal goals contribute to diminished feelings of authenticity. Gender can be an important part of this process insofar as certain ways of behaving within a particular context or role can conflict with goal orientations and values that are, to some extent, shaped by the socialization of gender stereotypes. Both role congruity theory (Eagly & Karau, 2002) and goal congruity theory (Diekman et al., 2017) emphasize how the prescriptive and proscriptive norms of gender stereotypes impact men and women across various roles. For example, the socialization of traditional role expectations for women (e.g., to be a warm caregiver) can lead them to adopt communal goals and values more than men (Diekman & Eagly, 2008), which in turn leads them to be (on average) more interested in roles that afford communal goal pursuits and less interested in those that do not (see Diekman et al., 2020). From an authenticity perspective, role behavior and demands that conflict with one’s goals and values should contribute to feelings of inauthenticity. The implication for gender is that the socialization of prescriptive and proscriptive gender norms can lead men and women to experience authenticity differently as a function of role specific demands and behaviors.

Consistent with this view, Dormanen et al. (2020) demonstrated that women will (on average) experience less authenticity when a context induces them to express characteristics that conflict with proscriptive gender norms. In this case, undergraduate women at a U.S. university were induced to express masculine characteristics (e.g., assertiveness) in a video-recorded mock interview. Women who were instructed to express masculine (vs. non-masculine) characteristics reported significantly lower feelings of authenticity after doing so. The interpretation was that the demand to express characteristics that did not “fit” with gender norms for women created a weakened sense of being authentic. Ong (2021) made a similar point when testing the effects of holding leadership positions on authenticity for men and women. Ong drew from role congruity theory (Eagly & Karau, 2002) to hypothesize that women (vs. men) in leadership positions, by nature of the normative expectations of leadership (i.e., assertiveness, dominance), would be compelled into behavioral patterns that were inconsistent with prevailing gender stereotypes for women to be less dominant and more communal than men (Eagly et al., 2020). The resulting lack of “fit” between leader role expectations and gender role expectations should consequently elicit feelings of inauthenticity. Results supported this prediction. In one experiment, women randomly placed into a leadership role reported feeling less authentic relative to men in the same leadership role, and they felt less authentic relative to women in a non-leadership role that did not conflict with gender norms. Thus, consistent with a “fit” view of subjective authenticity (Schmader & Sedikides, 2018), there is evidence that roles and behaviors that conflict with gender role expectations elicit diminished feelings of being authentic.

Gender and Authenticity as Parent

Normative expectations for men and women may also be relevant for understanding how men and women experience authenticity in their parenting role. The idea that people experience inauthenticity in roles that conflict with gender norms could mean that men will feel less authentic as parents than women. The content of stereotypes (Park & Banchefsky, 2018) for women and mothers, for example, feature largely overlapping characteristics (e.g., moms and women are both characterized as gentle, nurturing, attentive); whereas the content of stereotypes for men and fathers are much more distinct (e.g., men are characterized as intimidating and autocratic, but fathers are characterized as sympathetic and understanding). People also more strongly associate women with the role of mother than they associate men with the role of father, and women more strongly identify with the role of mother than men do with the role of father (Park & Banchefsky, 2019). Such patterns suggest that, in terms of the child caregiving role, women may experience more “fit” between role expectations and gender expectations, thereby leading to greater authenticity in that role relative to men.

At the same time, however, there may be meaningful differences that emerge as a function of specific behaviors within the parental caregiver role. A considerable body of research on parenting behaviors supports a broad framework consisting of distinct classes, or typologies, of parent caregiving practices (Baumrind, 1971). These typologies have been investigated in diverse cultural contexts (Sorkhabi, 2005) and can be understood as different configurations of two dimensions: demandingness/control and responsiveness/warmth (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Authoritative parenting practices, for example, involve the combination of firm but democratic control with high levels of warmth, acceptance, and appropriate-autonomy support. In contrast, authoritarian parenting is characterized by practices that are harsh and unresponsive, highly controlling, and dominantly exclude the child from reasoning about rules and punishment. Permissive parenting practices generally reflect high levels of warmth, support, and autonomy granting, but also feature very low levels of demandingness and control of child behavior. Finally, neglectful parenting practices are those that reflect low levels of responsiveness/warmth and low levels of demandingness; they instead reflect a sort of rejection of the caregiving role. Each of these distinct classes of parenting practices relate to important developmental outcomes, with authoritative parenting generally considered to be the “ideal” pattern for optimal child development (Larzelere et al., 2013), at least in Western cultures (Sorkhabi & Mandara, 2013). We propose that different parenting practices may differentially relate to authenticity within the role of parent for moms and dads.

This possibility is grounded in the research reviewed above suggesting that role-specific behaviors that do not fit with gender role expectations may undermine authenticity in that particular role. Research (e.g., Prentice & Carranza, 2002) has indeed revealed broad normative expectations for the characteristics that men and women should or should not express. Koenig (2018), for example, showed that American adults believe that men are expected to be agentic and to avoid showing weakness, while women are expected to be communal and to avoid expressing dominance. Multinational research further reveals “near universal evidence” for such norms (Bosson et al., 2022). Moreover, there are real consequences for violating these expectations, as both men and women who violate gender norms experience “backlash” in the form of negative social evaluations (Moss-Racusin et al., 2010; Rudman et al., 2012).

Authoritative parenting, at least conceptually, would not seem to directly conflict with these gender norm expectations for men and women. The warmth and democratic orientation that is characteristic of authoritative parenting aligns with the communal norms expected of women, while the firm levels of control inherent in authoritative parenting aligns with normative expectations for men to be assertive and avoid being weak (Koenig, 2018). We therefore would not expect authoritative parenting to predict parent-role authenticity differently for moms and dads. Given the broad desirability of authoritative parenting in Western cultural contexts (Sorkhabi & Mandara, 2013), we might actually expect an unmoderated positive association between authenticity and authoritative parenting in our sample. In contrast, we anticipate gender differences in the association between authoritarian parenting and parent-role authenticity. The harsh and dominant orientation of authoritarian practices do conflict with female gender norms emphasizing that women should be warm and not express dominance, but they do not conflict with male gender norms prescribing agency and proscribing expressions of weakness (Koenig, 2018). The lack of “fit” between authoritarian practices and female gender expectations may therefore produce a negative association between authoritarian parenting and parent-role authenticity in mothers. Gender differences should also emerge between permissive parenting and parent-role authenticity. Here, however, permissive practices that are high in warmth and low in parental control may conflict with the male proscriptive norm to avoid being weak and yielding (Koenig, 2018). Permissive parenting should consequently be negatively associated with parent-role authenticity for men.

The Current Study

Pulling from both theory (Schmader & Sedikides, 2018) and research (Ong, 2021) on authenticity, we predicted that a lack of “fit” between gender norms and parental caregiving behaviors would correspond to diminished parent-role authenticity within mothers and fathers. Although we expected women to feel more authentic in the parent caregiving role overall, permissive parenting practices were expected to negatively predict authenticity within men and authoritarian parenting practices were expected to negatively predict authenticity within women. Authoritative parenting practices were not expected to differentially predict authenticity within moms and dads. We tested these predictions in a three-wave repeated measure study that assessed the frequency of engaging in specific parenting behaviors and feelings of authenticity in the parenting role. This enabled us to assess how fluctuations in the expression of different parenting behaviors relates to parent-role authenticity dynamically within parents. These within-person associations were of primary interest given evidence that within-person variability in authenticity is linked to well-being (Landa & English, 2021). In addition, there is practical importance to understanding how individual fluctuations in parenting practices relate to authenticity within parents as they fulfill their parenting role.

Method

Participants

Parents (N = 533) of a child between the ages of 9 and 19 were recruited to participate in a three-wave online study. We utilized the panel service provided by CloudResearch TurkPrime to recruit participants from the United States. Four participants who failed to provide a child age or indicated that their child was younger than our inclusion criteria were excluded from analyses. Our decision to focus on children between the ages of 9 and 19 was grounded in our desire to constrain overall variance in child age. We had no specific predictions about child age limiting any of the predicted effects, however, and we found no evidence that child age moderated any of the effects reported below (see supplementary document). An additional participant was not included in analyses because they did not indicate their gender.

The final sample retained for analyses included 528 parents who identified as either male or female (348 females, 180 males) and ranged in age from 23 to 64 (M = 42.21 years, SD = 7.13 years). The racial make-up of the sample was White (422, 79.9%), Black or African-American (50, 9.5%), Asian (28, 5.3%), American-Indian/Alaska Native (4, 0.8%), Pacific Islander (2, 0.4%) and “other” (22, 4.2%). On average, parents reported having approximately two children (M = 2.16, SD = 1.23). The age of the child that parents reported on for this study ranged from 9 to 19 (M = 14.46 years, SD = 2.65 years) and most of the parents (505, 95.5%) reported being biologically related to the target child. Nearly all participants were high school graduates (525, 99.9%), over half were college graduates (299, 56.6%), and several possessed graduate degrees (41, 7.8%). Nearly forty-percent (206, 39.5%) of the sample reported a gross (before taxes) family income less than $51,000, 34.4% (180) reported a gross family income between $51,000 and $90,000, and 26.1% (136) reported a gross family income over $91,000.

Participants were compensated via cash or gift cards, based on the agreement they made with the CloudResearch TurkPrime paneling service. All compensation was equivalent to approximately $6.50 per survey, and participants who completed all three of the surveys received a one-time bonus payment. Most of the sample completed all three surveys (360, 68.2%) with 17.1% (90) completing only one survey and 14.7% (78) completing two surveys. We did not impute missing data values and, because linear mixed models are generally robust to missing data (Brown, 2021), included all participants in analyses regardless of completed surveys.

Power Considerations

Our goal was to recruit as many participants as possible given the resources available for compensation. We aimed to maximize our sample at Level 2 (total N), rather than maximize the Level 1 sample (observations) because simulations indicate that the Level 2 sample size has more impact on power for cross-level interactions (Scherbaum & Ferreter, 2009). We fully expected to be adequately powered, particularly given that observations were repeated within individuals. Our sample size exceeds the sample size needed for stable estimates of cross-sectional bivariate correlations (N = 250; Schönbrodt & Perugini, 2013) and the sample size needed (N = 434) to reliably test for three interaction effects in a cross-sectional multiple regression model with an estimated effect size that is typical of social and personality psychology (r = .21; Funder et al., 2014) and power set to 0.95.

Procedure

Participants were emailed a link to a survey on three separate occasions, spaced four days apart. This spacing was not guided by any particular theoretical position, but rather a general sense that it might allow for some degree of variability across assessment waves. Each survey only remained active for the day that it was sent to the participants and each survey took approximately 20 min to complete. Demographic information was recorded in Survey 1 only, but otherwise the surveys were identical across the days. The study was conducted in 2019, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. We describe the relevant materials below, but other measures were included in the surveys. All measures relevant to our primary hypotheses are reported in this manuscript and a description of the full survey is available in here: https://osf.io/9v4e3/?view_only=047b5b54399c469092ca165a42c109fd.

Materials

Parenting Practices

Due to space and time constraints, we selected 20 face-valid items from the 62-item Parenting Practices Questionnaire (Robinson et al., 1995) to assess differences in the utilization of distinct parenting practices. Eight items focused on authoritative practices characterized by parental warmth (e.g., “expressed warm affection to my child”) and democratic involvement (e.g., “allowed child to give input into family rules”); eight items focused on authoritarian practices characterized by hostility (e.g., “expressed anger towards child”), punitiveness (e.g., “used threats as punishment with little or no justification”), and directiveness (e.g., “demanded that my child do things”); and four items focused on permissive practices characterized by a lack of follow through implementing punishment (e.g., “made empty threats to child”). This measure does not assess the neglectful type of parenting practices and, as such, we did not consider that type of practice in this study.

During each wave of the study, parents indicated how much they engaged in each practice over the last four days based on a 0 (did not engage in the behavior at all) to 100 (engaged in the behavior all the time) scale. Responses were averaged into separate authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive practice composites, with higher scores reflecting a greater utilization of the practice over the previous four days. Descriptive and reliability statistics are provided in Table 1.

Authenticity as a Parent

We assessed parent role authenticity with an adapted version of the Authenticity Scale (Wood et al., 2008). The full measure consists of 12 items that assess three facets of authenticity: authentic living (expression of the true self), true self-alienation (not knowing or feeling disconnected from the true self), and acceptance of external influence. Our measure consisted of 6 items (2 face-valid items for each aspect) due to space and time limitations of this longitudinal study. We also adapted the measure to focus specifically on feelings of authenticity in one’s role as a parent. In each wave of the study, participants read the items and selected the number from the rating scale that best described the way they felt about their role as a parent over the last four days. Items included “In my role as a parent, I act in accordance with my values and beliefs” and “When I carry out this role, I am true to myself in most situations” (authentic living); “When I carry out this role, I feel as if I don't know myself very well” and “When I carry out this role, I don't know how I really feel inside” (self-alienation); and “In my role as a parent, I am strongly influenced by the opinions of others” and “I usually do what other people tell me to do when I carry out my role as a parent” (acceptance of external influence). Responses were made on 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely) scales and we reverse scored the self-alienation and acceptance of external influence items so that higher scores on all responses reflected greater feelings of authenticity. All items were averaged into a single Total Authenticity composite. Interested readers can find information pertaining to the separate authenticity facets, including analyses focused on each facet separately, in the supplementary materials.

Results

We first examined gender differences on the primary variables via a linear mixed model analysis with a random intercept. Women (M = 73.72, SE = 0.92), relative to men (M = 69.04, SE = 1.27) reported more authoritative parenting practices (b = -4.68, SE = 1.57, p = .003, 95% CI [-7.75, -1.60]; women (M = 14.68, SE = 0.87), relative to men (M = 18.59, SE = 1.20) reported less authoritatian parenting practices (b = 3.91, SE = 1.48, p = .008, 95% CI [1.01, 6.81]; women (M = 11.29, SE = 0.84) and men (M = 13.50, SE = 1.16) did not differ in permissive parenting practices (b = 2.20, SE = 1.43, p = .124, 95% CI [-0.60, 5.00]. In addition, and consistent with hypotheses, women (M = 5.89, SE = 0.05), relative to men (M = 5.66, SE = 0.07) reported feeling more authentic in the parenting role (b = -0.23, SE = 0.08, p = .005, 95% CI [-0.40, -0.07].

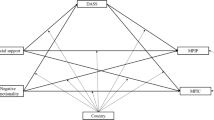

Our primary analyses, however, centered on the within-person relationships between parenting practices and parent-role authenticity. We ran a linear mixed regression analysis to test these within-parent associations and included parent gender in these analyses. We entered authenticity as an outcome variable, all three parenting dimensions as Level 1 (within-participant; cluster-centered) predictors, parent gender (dummy coded: female = 0, male = 1) as a Level 2 (between-participant) predictor, and the three Parent Gender x Parenting Dimension cross-level interactions. The model included a random intercept and were carried out using the GAMLj module (Gallucci, 2019) in Jamovi v2.2 (The Jamovi Project, 2021). We probe the significant interaction effects in the text below. All results below remain significant when controlling for demographic variables (e.g., parent education, household income, age of child; see supplementary information).

Table 2 presents the full results. As intimated above, there was a significant main effect (between-person) of parent gender. Men felt less authentic in their parent role overall than women did. There was also a significant positive main effect (within-person) of authoritative parenting that was not qualified by parent gender. Both mothers and fathers reported a greater sense of authenticity when they demonstrated higher levels of authoritative parenting relative to their own typical levels. Two significant Parent Gender x Parenting Dimension interactions also emerged.

A significant Parent Gender x Authoritarian Parenting interaction (Fig. 1) revealed that authoritarian parenting negatively predicted authenticity for mothers (b = -.013, SE = .003, p < .001, 95% CI [-.019, -.008]), but not for fathers (b = .005, SE = .004, p = .140, 95% CI [-.002, .012]. This indicates that moms, but not dads, felt less authentic during periods when they engaged in more authoritarian practices than was typical for them.

In contrast, a significant Parent Gender x Permissive Parenting interaction (Fig. 2) revealed that permissive parenting negatively predicted authenticity for fathers (b = -.011, SE = .004, p = .012, 95% CI [-.019, -.002], but not for mothers (b = .003, SE = .003, p = .350, 95% CI [-.003, .001]. This indicates that dads, but not moms, felt less authentic during periods when they engaged in more permissive practices than was typical for them.

Discussion

The results supported our hypotheses. On average, mothers felt more authentic in the role of parent than did fathers. Within-parent fluctuations in parenting practices were also differentially associated with parent-role authenticity as a function of gender. Authoritative practices characterized by warmth and democratic control positively predicted authenticity in the parent role for both mothers and fathers. This might reflect the fact that authoritative practices do not directly conflict with prevailing gender norms and the possibility that authoritative practices were socially desirable in our sample. Indeed, authoritative practices are considered ideal in Western contexts (Larzelere et al., 2013) and authenticity tends to covary with the expression of socially desirable traits (Fleeson & Wilt, 2010). In contrast, authoritarian parenting practices were negatively associated with authenticity within mothers, and permissive parenting practices were negatively associated with authenticity within fathers. These patterns suggest that fluctuations in different kinds of parenting behaviors relate to authenticity differently for moms and dads.

In this way, our findings broadly connect to research linking the fit between gender norms and role-behaviors to the experience of authenticity. Dormanen et al. (2020) showed that women who expressed masculine characteristics that violated proscribed gender norms reported lower levels of authenticity than those who expressed non-masculine characteristics, and Ong (2021) demonstrated that women in positions of authority reported lower levels of authenticity than women who did not hold positions of authority. Our findings can similarly be interpreted as supporting some of the predictions of the “state-authenticity-as-fit” model of authenticity (Schmader & Sedikides, 2018). A key aspect of this model is that acting in ways that do not align with normative expectations negatively affect feelings of authenticity. Our study provides support for these predictions in the context of parenting. Parenting that conflicted with normative expectations for women to avoid being dominant negatively predicted mothers’ authenticity; parenting that conflicted with normative expectations for men to avoid being weak negatively predicted fathers’ authenticity.

The present research also invites theorizing about the potential importance of authenticity in parents. Considerations of authenticity in parenting remain scant. One study (Hammond et al., 2021) showed that the link between breastfeeding difficulties and depressive symptoms is dampened in mothers who experience relatively high levels of parent-role authenticity. Such findings suggest that parent-role authenticity buffers the negative psychological consequences of parenting difficulties, which aligns with other findings on the psychological security afforded by authenticity (Vess et al., 2014). Here, it is perhaps notable that we observed an overall main effect of gender on parent-role authenticity. Mothers, on average, were higher in parent role authenticity than fathers. This pattern is consistent with the finding that women identify more strongly with the role of mother than men do with the role of father (Park & Banchefsky, 2019), and it might inform potential gender differences in various aspects of the caregiver role. For example, authenticity is a robust predictor of motivation (Maffly-Kipp et al., 2022), which implies that these differences in authenticity between moms and dads might explain some variance in the motivation to engage in specific parenting duties within families. In the U.S., where mothers disproportionately fulfill childcare duties (Schoonbroodt, 2018), men also report a weaker preference for childcare tasks relative to women (Bleske-Rechek & Gunseor, 2022) and may be particularly influenced by norms surrounding the parenting role (Maurer, 2007). Our findings identify a potential mechanism, authenticity in the parenting role, to examine in relation to such patterns and further articulate the psychological processes that underlie them.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the current findings are important to keep in mind. First, and related to the discussion above, our study focused on a narrow view of parenting in terms of the practices that mothers and fathers employed to parent their children. This was intentional in that our focus was on relationships between certain parenting practices and parent-role authenticity. There are, however, many other related and distinct aspects of the parenting role. It might be especially notable that we did not assess features of the “breadwinner” role (e.g., providing financial stability), which fathers tend to identify with more strongly than women (Park & Banchefsky, 2019). Given the gendered norms surrounding the role of provider within a family, we might expect fathers to feel more authentic in that role than mothers. Future research should consider that possibility in order to more broadly inform the relevance of authenticity within family processes.

Our study is also not positioned to consider the role of culture or intersectionality (Shields, 2008) in these effects. For example, theory and research (Dwairy et al., 2006) suggests that authoritarian parenting may be more normative in more collectivist cultures, and there is at least some evidence that authoritarian and permissive parenting effects are less consequential for child outcomes in certain collectivistic contexts (Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). Similarly, while women are generally expected to be less dominant/authoritarian than men, there is some evidence that authoritarian parenting practices are more common among African-American mothers relative to European-American mothers (Lansford et al., 2011). It is thus possible that parenting practices may be experienced as more or less authentic as a function of cultural differences and/or social identities beyond gender. Our findings are silent about the generalizability of these effects beyond predominantly White cisgender mothers and fathers of relatively older children in a Western cultural context.

It is also notable that, while our findings are consistent with past work on gender roles/norms and authenticity (Ong, 2021), we did not assess participants’ identification with those norms. At least one study has found that the effect of expressing masculinity on authenticity is stronger for women who identify relatively higher with femininity (Dormanen et al., 2020), suggesting that gender identification might be relevant for the present effects. Though it might be difficult to fully eliminate the influence of broad social norms regarding gender, as evidenced by persistent gender disparities in childcare responsibilities despite continuing gains in women’s workforce representation (cf. Park & Banchefsky, 2019), future research should build on our findings to test whether the present effects are moderated by identification with, or the situational salience of, relevant gender norms.

Finally, our study is limited by some of its methodology. We relied on a convenience sample collected from an online paneling service and employed abbreviated adaptations of established measures, which might introduce concerns about generalizability and the measurement of authenticity and parenting practices. Our measures did relate in expected ways, were reliable across measurement occasions, and squarely focused on the aspects of authenticity and parenting practices that were most central to our theorizing. Studies using full measurement scales, however, could provide additional confidence in the validity of our approach. A measure of neglectful parenting (i.e., low demandingness/control and low responsiveness/warmth; see Baumrind, 1971) was also not featured in our chosen parenting measure, leaving questions about how neglectful parenting might relate to authenticity. Similarly, while the utilization of self-report measures of parenting practices is common, studies that assess parenting via multi-method approaches (e.g., child-report, behavioral) may prove useful. Such investigations could further the understanding of how parenting practices relate to authenticity within mothers and fathers and potentially inform intrapersonal versus interpersonal aspects of authenticity. It could very well be the case that parents’ perceptions of their behavior are more critical for their authenticity than observer ratings, but that has not been empirically established. Experimental studies that test the causal associations between our primary variables are also warranted.

Practice Implications

Despite these limitations, our study may contribute to future research and have a potentially significant broader impact. Given the link between authenticity and eudemonic well-being (Rivera et al., 2019), our findings complement the robust literature on parenthood and happiness (Nelson et al., 2014) by identifying one way in which specific parenting practices influence a self-relevant experience that is central to meaning and purpose. Authoritative practices, for example, were positive predictors of authenticity for both moms and dads. This might suggest that efforts to enhance authoritative practices could be useful for both the wellbeing of children and parents, at least in contexts where those practices produce culturally valued outcomes (Sorkhabi & Mandara, 2013).

In addition, insofar as our studies reveal the potential well-being costs associated with gendered expectations around parenting, our studies also suggest that practitioners and influencers should avoid accentuating links between the parenting role and gender. Fathers report frustration with parenting websites, for example, because they are too focused on the experience of mothers (Plantin & Daneback, 2009). Such disparity in social portrayal of parenting might only serve to reinforce the gender norms that underlie some of the effects reported here. And, because authenticity has motivational properties (Dormanen et al., 2020; Maffly-Kipp et al., 2022; Schmader & Sedikides, 2018), our results suggest that the explicit and implicit messaging around parenting could have an important effect on people’s desire for and commitment to different roles within the family.

Conclusion

The present study provides evidence that parenting practices are associated with the experience of authenticity in one’s parenting role. Parenting that is generally incongruent with gender role expectations feels less authentic in mothers and fathers. This was the case for permissive parenting within dads and authoritarian parenting within moms. In contrast, authoritative parenting was positively associated with parent-role authenticity for moms and dads, but moms experienced more authenticity in the parent role overall. These findings connect theory and research on authenticity to research on parenting, and shed light on the ways that mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors connect to a self-relevant experience central to psychological flourishing (Rivera et al., 2019). At least for the experience of feeling authentic, how mothers and fathers feel in their parenting role appears to be shaped by social norms about how men and women should behave.

Data Availability

All data and materials are accessible on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9v4e3/?view_only=047b5b54399c469092ca165a42c109fd).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Angelov, N., Johansson, P., & Lindahl, E. (2016). Parenthood and the gender gap in pay. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(3), 545–579. https://doi.org/10.1086/684851

Baumeister, R. F. (2019). Stalking the true self through the jungles of authenticity: Problems, contradictions, inconsistencies, disturbing findings—and a possible way forward. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268019829472

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4(1, Pt.2), 1–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030372

Bleske-Rechek, A., & Gunseor, M. M. (2022). Gendered perspectives on sharing the load: Men’s and women’s attitudes toward family roles and household and childcare tasks. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 16(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000257

Bosson, J. K., Wilkerson, M., Kosakowska-Berezecka, N., Jurek, P., & Olech, M. (2022). Harder won and easier Lost? Testing the double standard in gender rules in 62 countries. Sex Roles, 87, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01297-y

Brown, V. A. (2021). An introduction to linear mixed-effects modeling in R. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 4(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245920960351

Christy, A. G., Seto, E., Schlegel, R. J., Vess, M., & Hicks, J. A. (2016). Straying from the righteous path and from ourselves: The interplay between perceptions of morality and self-knowledge. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(11), 1538–1550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216665095

Cooper, A. B., Sherman, R. A., Rauthmann, J. F., Serfass, D. G., & Brown, N. A. (2018). Feeling good and authentic: Experienced authenticity in daily life is predicted by positive feelings and situation characteristics, not trait-state consistency. Journal of Research in Personality, 77, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.09.005

Diekman, A. B., Joshi, M. P., & Benson-Greenwald, T. M. (2020). Goal congruity theory: Navigating the social structure to fulfill goals. In B. Gawronski (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol 62, pp. 189–244). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2020.04.003

Diekman, A. B., & Eagly, A. H. (2008). Of men, women, and motivation: A role congruity account. In J. Y. Shah & W. L. Gardner (Eds.), Handbook of motivation science (pp. 434–447). The Guilford Press.

Diekman, A. B., Steinberg, M., Brown, E. R., Belanger, A. L., & Clark, E. K. (2017). A goal congruity model of role entry, engagement, and exit: Understanding communal goal processes in STEM gender gaps. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(2), 142–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868316642141

Dormanen, R., Sanders, C. S., Maffly-Kipp, J., Smith, J. L., & Vess, M. (2020). Assimilation undercuts authenticity: A consequence of women’s masculine self-presentation in masculine contexts. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(4), 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684320947648

Dwairy, M., Achoui, M., Abouserie, R., & Farah, A. (2006). Parenting styles, individuation, and mental health of Arab adolescents: A third cross-regional research study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(3), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106286924

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., & Sczesny, S. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of US public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. American Psychologist, 75(3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000494

Fleeson, W., & Wilt, J. (2010). The relevance of big five trait content in behavior to subjective authenticity: Do high levels of within-person behavioral variability undermine or enable authenticity achievement? Journal of Personality, 78(4), 1353–1382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00653.x

Funder, D. C., Levine, J. M., Mackie, D. M., Morf, C. C., Sansone, C., Vazire, S., & West, S. G. (2014). Improving the dependability of research in personality and social psychology: Recommendations for research and educational practice. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(1), 3–12.https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313507536

Gallucci, M. (2019). GAMLj: General analyses for linear models. [Jamovi module]. https://gamlj.github.io/

Hammond, M., Brooker, R. J., Mistry-Patel, S., Schlegel, R. J., Vess, M., Wines, M., & Havens, J. (2021). Feelings of parental authenticity moderate concurrent links between breastfeeding experience and symptoms of postpartum depression. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 2, 25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2021.651244

Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 38, pp. 283–357). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38006-9

Koenig, A. M. (2018). Comparing prescriptive and descriptive gender stereotypes about children, adults, and the elderly. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01086

Landa, I., & English, T. (2021). Variability in state authenticity predicts daily affect and emotion regulation. Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001017

Lansford, J. E., Bornstein, M. H., Dodge, K. A., Skinner, A. T., Putnick, D. L., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2011). Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in the United States. Parenting, Science and Practice, 11(2–3), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2011.585567

Larzelere, R. E., Morris, A. S., & Harrist, A. W. (Eds.). (2013). Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13948-000

Lenton, A. P., Slabu, L., & Sedikides, C. (2016). State authenticity in everyday life. European Journal of Personality, 30(1), 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2033

Lenton, A. P., Slabu, L., Sedikides, C., & Power, K. (2013). I feel good, therefore I am real: Testing the causal influence of mood on state authenticity. Cognition and Emotion, 27(7), 1202–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.778818

Maccoby E. E., & Martin J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Mussen, P.H., & Hetherington M.E. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4 Socialization personality, and social development (pp. 1–101). John Wiley.

Maffly-Kipp, J., Holte, P. N., Stichter, M., Hicks, J. A., Schlegel, R. J., & Vess, M. (2022). Civic hope and the perceived authenticity of democratic participation. Social Psychological and Personality Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506221107261

Maurer, T. W. (2007). Gender congruence and social mediation as influences on fathers' caregiving. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research & Practice about Men as Fathers, 5(3), 220–235. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0503.220

Morgan, A. C., Way, S. F., Hoefer, M. J. D., Larremore, D. B., Galesic, M., & Clauset, A. (2021). The unequal impact of parenthood in academia. Science Advances, 7(9), Article eabd1996. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd1996

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). When men break the gender rules: Status incongruity and backlash against modest men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(2), 186–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01561.x

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being? Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 846–895. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035444

Nelson-Coffey, S. K., Killingsworth, M., Layous, K., Cole, S. W., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2019). Parenthood is associated with greater well-being for fathers than mothers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(9), 1378–1390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219829174

Ong, W. J. (2021). Gender-contingent effects of leadership on loneliness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(7), 1180–1202. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000907

Park, B., & Banchefsky, S. (2018). Leveraging the social role of dad to change gender stereotypes of men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(9), 1380–1394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218768794

Park, B., & Banchefsky, S. (2019). Women and men, moms and dads: Leveraging social role change to promote gender equality. In J. M. Olson (Ed.). Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1–52). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2018.10.001

Pinquart, M., & Kauser, R. (2018). Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(1), 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000149

Plantin, L., & Daneback, K. (2009). Parenthood, information and support on the internet. A literature review of research on parents and professionals online. BMC Family Practice, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-10-34

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(4), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Rivera, G. N., Christy, A. G., Kim, J., Vess, M., Hicks, J. A., & Schlegel, R. J. (2019). Understanding the relationship between perceived authenticity and well-being. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 113–126.

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77(3), 819–830. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.819

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Glick, P., & Phelan, J. E. (2012). Reactions to vanguards: Advances in backlash theory. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 45, pp. 167–227). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00004-4

Scherbaum, C. A., & Ferreter, J. M. (2009). Estimating statistical power and required sample sizes for organizational research using multilevel modeling. Organizational Research Methods, 12(2), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107308906

Schmader, T., & Sedikides, C. (2018). State authenticity as fit to environment: The implications of social identity for fit, authenticity, and self-segregation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(3), 228–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868317734080

Schönbrodt, F. D., & Perugini, M. (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality, 47(5), 609–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.05.009

Schoonbroodt, A. (2018). Parental child care during and outside of typical work hours. Review of Economics of the Household, 16(2), 453–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9336-y

Sedikides, C., Lenton, A. P., Slabu, L., & Thomaes, S. (2019). Sketching the contours of state authenticity. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000156

Sedikides, C., Slabu, L., Lenton, A., & Thomaes, S. (2017). State authenticity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 521–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417713296

Shields, S. A. (2008). Gender: An intersectionality perspective. Sex Roles, 59(5), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9501-8

Sorkhabi, N. (2005). Applicability of Baumrind’s parent typology to collective cultures: Analysis of cultural explanations of parent socialization effects. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 552–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250500172640

Sorkhabi, N., & Mandara, J. (2013). Are the effects of Baumrind's parenting styles culturally specific or culturally equivalent? In R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 113–135). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13948-006

Sutton, A. (2020). Living the good life: A meta-analysis of authenticity, well-being and engagement. Personality and Individual Differences, 153, 109645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109645

The jamovi project. (2021). jamovi. (Version 2.2) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2003). Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00574.x

van den Bosch, R., & Taris, T. W. (2014). Authenticity at work: Development and validation of an individual authenticity measure at work. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9413-3

Vess, M. (2019). Varieties of conscious experience and the subjective awareness of one’s “true” self. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268019829471

Vess, M., Schlegel, R. J., Hicks, J. A., & Arndt, J. (2014). Guilty, but not ashamed: “True” self-conceptions influence affective responses to personal shortcomings. Journal of Personality, 82(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12046

Wood, A. M., Linley, A. P., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authenticity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.385

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Matthew Vess; Methodology: Matthew Vess; Formal Analysis and investigation: Matthew Vess; Writing – original draft: Matthew Vess, Joseph Maffly-Kipp; Writing – reviewing and editing: Matthew Vess, Joseph Maffly-Kipp.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This research was approved by the Texas A&M University Human Subjects Protection Program (IRB).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest/Competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Vess, M., Maffly-Kipp, J. Parenting Practices and Authenticity in Mothers and Fathers. Sex Roles 87, 487–497 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01330-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01330-0