Abstract

Amid an increasingly demanding research environment, there has been a growing interest in studies concerning Research Integrity and Research Ethics (RIRE). Between 1990 and 2020, over 9700 publications were published to address problematic research conduct such as falsification, plagiarism, and related protocols and standards. In this work, country-level trends and collaborative structures are examined with respect to economic group. Our results showed that RIRE publications are predominantly led by the West, with North America and Western Europe contributing the most. While there is interest within growing economies such as China, the pace is not comparable to its overall publications. However, international collaborations on RIRE grew to account for nearly 30% of all publications on the subject in 2020. Although there is a stronger preference for high income countries to collaborate with other high income countries, we observe a rise in partnerships between high-/middle-income and middle-/lower-income co-authorship pairs in the last decade. These trends point to a maturing global community with distributed knowledge transfer, towards more unified international standards for research ethics and integrity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past decades, the number of scientific publications has increased exponentially (Bornmann et al., 2021; Powell et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2015) fuelled by societal and commercial interests. These are evidenced by growing R&D funding, increase in the number of researchers, expanded international collaborations, commercialization potential, and the participation of emerging countries (Bhattacharya, et al., 2015; Javed & Liu, 2018; Moiwo & Tao, 2013; Shashnov & Kotsemir, 2018). Alongside the escalating research landscape, ethics and integrity continues to serve as a basis for good and wholesome research practices. The necessity and shared responsibility of all stakeholders to uphold standards and principles is expected to continue to grow as more countries commit to funding research and more researchers contribute to the knowledge base (Titus et al., 2008). Where research ethics defines the standard framework of acceptable conduct in research (Resnik, 2020), research integrity represents the adherence of conduct to ethical principles which renders trust and confidence in the given methods and results. Both are complementary in supporting responsible scientific conduct (Bird, 2006; Braun et al., 2020). The absence of either facet can have potentially dire consequences which could erode public trust in research. Clinical research without ethical protocols can marginalize vulnerable study participants (Schüklenk, 2000). Flippant or perfunctory conduct, skewed or exaggerated data, or outright fraudulent results have the potential to misdirect future paths of research (Bouter et al., 2016; Coxon et al., 2019). Poor research may also mislead or misinform policymakers, thereby undermining government support for research in terms of its reliability and future funding (Michalek et al., 2010). Researchers and institutions also face increasing competition, pressure and demands (Haven et al., 2019), potentially leading to corner cutting or compromising of standards.

The ongoing discourse led to flourishing Research Ethics and Research Integrity (RIRE)-related fields (Aubert Bonn & Pinxten, 2019). In the last 10–15 years, the number of retractions have increased (Steen et al., 2013), signalling a greater awareness and identification of appropriate publication conduct (Fanelli, 2013). Several journals are dedicated to the subject, with some serving areas of specialization with titles including Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, Journal of Medical Ethics, The Journal of Ethics, Science and Engineering Ethics, Ethics and Information Technology, and Teaching Ethics. Moreover, institutions are adopting policies and regulations to promote good practices (Geller et al., 2010; Lins & Carvalho, 2014). In research, there is increasing multinational collaboration, and more publications have a diverse representation of country authorship (Jiang et al., 2018; Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2008). These partnerships are valued for its potential to raise impact (Guerrero Bote et al., 2013), visibility, creativity, and present opportunities for resource-sharing, knowledge transfer, and training (Freshwater et al., 2006; Khor & Yu, 2016; Rodrigues et al., 2016; RoyalSociety, 2011). Recent events such as the coronavirus pandemic that started in 2019 underlined the need for global collaborative efforts in science (Li et al., 2020). Multinational cooperation could additionally serve as a medium for policy transfer (Stone, 2012). In light of these factors, we examine the collaborative publishing trends on the international scale for RIRE-related research in the past three decades. Considering the global nature of research (Rodrigues et al., 2016), and by proxy, research integrity and ethics, we aim to characterize the current patterns in RIRE. In particular, is there an indication of knowledge flows and cooperation between scientifically advantaged countries and emerging countries?

Data set and methods

Dimensions (Digital Science) was used as the database for study, with publication ranges between 1990 and 2020, spanning 31 years, where publications of type “article” were included. The date range has been modified from an earlier version to include 2019 and 2020, which used Web of Science (WoS) as the database. The database change aimed to improve representation of regional and local publications (e.g. regional journals which may not be indexed). A title and abstract search was conducted for publications containing keywords related to RIRE using Dimensions BigQuery with the following terms: “research integrity” OR “research ethics” OR “scientific ethics” OR “scientific integrity” OR “research dishonesty” OR “scientific dishonesty” OR “scientific misconduct” OR “research misconduct” OR “publication misconduct” OR “misconduct in research” OR “ethics in research” OR “integrity in research” OR “research plagiarism” OR “research falsification” OR “plagiarism in research” OR “falsification in research” (Supplementary Information). Articles without a publisher were excluded. In total 11,895 unique publications were found. Publications were further narrowed to those which contained organization identifiers, in order to identify organization countries. DOIs of publications without organization identifiers were matched against entries in a Scopus (Elsevier) search. Organization countries were identified through the SciVal module (Elsevier) and merged with Dimensions data. The total number of unique publications after pre-processing was 9742.

World Bank economy group data was obtained for the most recent financial year (FY2022) and harmonized with country name data. The World Bank economy classification is based on the Gross National Income (GNI) values. Research participation was measured by full counting aggregated by time. Subject to National Output is computed as the ratio of RIRE-related paper relative to the national output.

For publication classification, a supervised machine learning classifier based on support vector machines (SVM) was implemented to examine topics of publication within RIRE. SVM was chosen due to its performance compared to other supervised classification algorithms (Goh et al., 2020). Compared to models such as the random forest classifier, SVM yielded the highest accuracy (82%). Labels were identified based on a multi-institutional study on research integrity (Mejlgaard et al., 2020) consisting of nine key areas to promote organizational research integrity. The training set consisted of publications based on themes of the nine outlined topics (Mejlgaard et al., 2020). These were identified using the Dimensions “Similar Documents” module on the web app, providing up to 2000 of the most conceptually similar papers for each topic.

Results and discussion

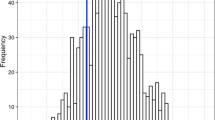

Between 1990 and 2020, yearly publications on RIRE have risen (Fig. 1, primary axis), with a cumulative total of 9742 publications. The year-on-year publication count increased from 37 in 1990 to 1265 in 2020, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.5%. Of these, 2048 publications involved more than one country, representing 21% of all publications in the dataset. In the early 1990s, efforts were concentrated to national-level publishing which consisted of upper middle to high income economies. A trend reversal is seen in the 2000s with multinational publications and is consistent with observed trends of research globalization (Barjak & Robinson, 2008; Wagner et al., 2015). Multinational publications from 1998 onwards saw a CAGR of 12.3%, and made up ~30% of all global publications by 2020.

In country-level breakdown of publications and international collaboration proportions (Fig. 2), high income (H) countries publish the most on RIRE-related topics. Global averages for output and international collaboration proportions at 131 and ~60% respectively, where low income countries publish at orders of magnitude lower compared to the average and exhibit international collaboration proportions which are above average. India, China, South Africa, and Brazil are notable middle income economies with comparable output and collaboration with leading high income groups. The United States leads in publishing volume with 2444 cumulative publications, followed by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Brazil, Germany, South Africa, Netherlands, and China (Fig. 2). Brazil counts for amongst the lowest in international collaboration proportions, and note that there is a preference to publish in local medical journals in a non-English language. RIRE papers relative to national output comprised a comparatively lower proportion for the United States, China, and India, ranging between 0.01 and 0.029% of all publication output for the year of 2020. Although RIRE contributions by proportion may appear stagnant, the volume from which these countries contribute are growing. By contrast, RIRE accounts for growing proportions of the national output in countries such as South Africa, Brazil, and the United Kingdom (0.07–0.14%). RIRE-related research within the emerging countries follows behind high income countries. This may be attributed to national research priorities, delay in participation, or ongoing development and enforcement of research ethics and integrity policies within the institutions (Ana et al., 2013; Fanelli et al., 2015; Okonta & Rossouw, 2014). As an example, activity from emerging economies such as India and China, classified as lower-middle and upper-middle income economies respectively, were recorded in the mid-2000s (Fig. 3).

International collaboration is examined from an economic perspective, based on the frequency of income group collaboration (Fig. 4). Annualized data shows that the highest activity occurs among high income (H) countries exclusively. Collaborations amongst low income (L) countries were not recorded. This result is not unexpected, where the absence may be due to the significant barriers faced by countries of this cohort, including lower research readiness and capacity arising from resource, infrastructural and logistical limitations. Interestingly, no H–L collaboration structures were recorded. Meanwhile, middle and low economy activity pairs (L–UM; L–LM) are sporadic, while exclusively middle income (LM–UM) collaboration pairs recorded a tenfold increase in the last 10 years. H–L collaborations are observed to appear in combination with a middle economy (LM/UM). Between 2006 and 2020, the number of H collaborations increased by 14 times. For the same period, H- pairings with upper-middle (UM) and lower-middle (LM) income economies increased by approximately greater than 21 times. These findings suggest there is knowledge transfer, although it is coupled with economic stratification. Middle income economies are in a unique position in the knowledge flow with ties to more scientifically advanced countries and can potentially serve as an intermediary for low-income economies with increasing adoption of ethics-related regulations. For example, the Chinese government developed ethics-related policies and established oversight committees (Cyranoski, 2018; Qiu, 2015; Yi et al., 2017; Zeng & Resnik, 2010) to address its RIRE deficiencies. The significant repercussions on offending researchers may reach far beyond academic careers (Cyranoski, 2018), including the possibility of facing restrictions on jobs, loans, and business opportunities.

To identify the topics which of interest to the research community, we classify the publications into nine groups, namely: (1) Research environment; (2) Supervision and mentoring; (3) Research integrity and training; (4) Research ethics structures; (5) Dealing with breaches of research integrity; (6) Data practices and management; (7) Research collaboration; (8) Declaration of interests; and (9) Publication and communication (Mejlgaard et al., 2020). In recent years, publications predominantly fall under ‘Research ethics and structures’ (Fig. 5), at 5804 publications. Research ethics addresses the protocols and policies for adherence in conducting scientific investigation. Biomedical ethics in particular pertains to clinical research methodology, with keywords such as ‘institutional review board’, ‘informed consent’, and ‘ethics committees’ which are prevalent across titles and abstracts. Bioethics represents a specialized case in biomedical and medical research, addressing social values in medical ethics (e.g. decision-making, dignity, euthanasia, death, quality of life), or concerns intersecting with biotechnology (e.g. cloning, stem cells), all of which benefit from the consensus of international alliances, consortiums, and working groups (Isasi, 2012). The average number of countries per paper was found to be 1.37, indicating less than two countries collaborating per paper, and suggests less papers at the international collaboration level. This value is on par with the average for all publications at 1.35 countries per publication where single authorship occurs more than international collaborations. For example, in ‘Research ethics structures’, the authorship collaboration matrix (Fig. 6) and ranking shows that the high-income group leads with 4199 papers and associated with a single country (Fig. 7). This configuration is followed, with a significant gap, by upper middle income countries. The prevalence of single country authorship as the preferred authorship structure may arise from factors such alignment with national-level research policies, and the simpler logistics compared to international collaboration (Dusdal & Powell, 2021). By comparison, the publication gap between a national-level LM country and an instance of collaboration is considerably smaller (LM = 1; H–LM = 2).

Conclusions

In this study, bibliometric analysis capture and characterize the macroscopic trends within the broader RIRE research community. The results indicate that while RIRE productivity has continued to grow between 1990 and 2020, there are variations between countries on factors such as topics of publication and rate of growth. Several key areas are found within RIRE research, including research integrity, bioethics, scientific misconduct, and plagiarism, which exhibit some geographic dependence, with countries of greater centrality exhibiting a broader scope of topic coverage. Top contributors of RIRE research and collaboration partners are generally dominated by wealthier nations such as the United States, England, Canada, Australia, Germany, and France, with typical collaboration pairings amongst fellow top publishers such as US–Canada and US–United Kingdom. These high-income countries are scientifically advantaged and may have the first mover lead in terms of research. However, we find that emerging countries have a growing presence in global research participation, and in some cases outpacing more developed and counterparts, RIRE-related publications do not follow the subject share proportion growth rates in the same manner. There are strong signals for the emerging trend of H–UM and UM–LM collaborations. The H–LM–UM joint papers have also increased × 8during 2007–2020. This signals a global growing trend towards a collaborative effort to transfer knowledge and deepened the knowledge on RIRE.

Based on current trends, we expect there will be a sustained interest and discourse in RIRE topics as research integrity and research ethics are universal concerns (Bouter, 2020) for several reasons. First, the credibility and research reputation of an institution is intimately tied to its ability produce quality research with good accountability (Hudson, 2008). There is added visibility from publicly available databases which monitor research activities, such as Retraction Watch, conferences such as the World Conference on Research Integrity, and the formal adoption of research frameworks. Currently, countries and institutions (Aubert Bonn et al., 2017) have substantially different norms and standards governing scientific work (Leshner & Turekian, 2009) and international collaboration. However, there is evidence that the scientific community observes value in the transnational partnerships. The proportion of international collaborations is at an all-time high at 29% between 1990 and 2020. The relative decrease of single country papers, and the increase of two or multiple countries indicates that joint papers in RIRE are involving more countries, institution, and authors. As more institutions adopt initiatives such as formal structured training (DuBois et al., 2008; Ferguson et al., 2007; Satalkar & Shaw, 2019; Sponholz, 2000), there may be more opportunities for further collaboration and communication towards harmonizing standards to promote more uniform global research practices (Frankel et al., 2016). Secondly, the scope of topics is expected to change depending on factors such as relevance to the publishing country or funding agency, and forthcoming applications or technologies. As an example, bioethics is largely affected by the developments within the sector, such as stem cells, gene editing using CRISPR technology, and cloning. With the integration of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data permeating sectors including the medical practice (e.g. patient data records and collection, genomic data and physiologic data) as well as cybersecurity, we expect that the future discourse would evolve accordingly, dictated by prevailing innovations and commercialization.

References

Ana, J., Koehlmoos, T., Smith, R., & Yan, L. L. (2013). Research misconduct in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Medicine, 10(3), e1001315. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001315

Aubert Bonn, N., Godecharle, S., & Dierickx, K. (2017). European universities’ guidance on research Integrity and misconduct: Accessibility, approaches, and content. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 12(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264616688980

Aubert Bonn, N., & Pinxten, W. (2019). A Decade of empirical research on research integrity: What have we (Not) looked at? Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 14(4), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264619858534

Barjak, F., & Robinson, S. (2008). International collaboration, mobility and team diversity in the life sciences: Impact on research performance. Social Geography, 3(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.5194/sg-3-23-2008

Bhattacharya, S., Shilpa, & Kaul, A. (2015). Emerging countries assertion in the global publication landscape of science: A case study of India. Scientometrics, 103(2), 387–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1551-4

Bird, S. J. (2006). Research ethics, research integrity and the responsible conduct of research. Science and Engineering Ethics, 12(3), 411–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-006-0040-9

Bornmann, L., Haunschild, R., & Mutz, R. (2021). Growth rates of modern science: A latent piecewise growth curve approach to model publication numbers from established and new literature databases. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00903-w

Bouter, L. (2020). What research institutions can do to foster research integrity. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(4), 2363–2369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00178-5

Bouter, L. M., Tijdink, J., Axelsen, N., Martinson, B. C., & Riet, Gt. (2016). Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: Results from a survey among participants of four world conferences on research integrity. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 1(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5

Braun, R., Ravn, T., & Frankus, E. (2020). What constitutes expertise in research ethics and integrity? Research Ethics, 16(1–2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016119898402

Coxon, C. H., Longstaff, C., & Burns, C. (2019). Applying the science of measurement to biology: Why bother? PLoS Biology, 17(6), e3000338. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000338

Cyranoski, D. (2018). Social punishments for scientific misconduct. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07740-z

DuBois, J. M., Dueker, J. M., Anderson, E. E., & Campbell, J. (2008). The development and assessment of an NIH-Funded research ethics training program. Academic Medicine, 83(6), 596–603. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181723095

Dusdal, J., & Powell, J. J. W. (2021). Benefits, motivations, and challenges of International Collaborative Research: A sociology of science case study. Science and Public Policy, 48(2), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scab010

Fanelli, D. (2013). Why growing retractions are (Mostly) a good sign. PLoS Medicine, 10(12), e1001563. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001563

Fanelli, D., Costas, R., & Larivière, V. (2015). Misconduct policies, academic culture and career stage, not gender or pressures to publish, affect scientific integrity. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0127556. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127556

Ferguson, K., Masur, S., Olson, L., Ramirez, J., Robyn, E., & Schmaling, K. (2007). Enhancing the culture of research ethics on university campuses. Journal of Academic Ethics, 5(2–4), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-007-9033-9

Frankel, M. S., Leshner, A. I., & Yang, W. (2016). Research integrity: Perspectives from China and the United States. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 847–866). Springer.

Freshwater, D., Sherwood, G., & Drury, V. (2006). International research collaboration. Journal of Research in Nursing, 11(4), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987106066304

Geller, G., Boyce, A., Ford, D. E., & Sugarman, J. (2010). Beyond “compliance”: The role of institutional culture in promoting research integrity. Academic Medicine, 85(8), 1296–1302. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e5f0e5

Goh, Y. C., Cai, X. Q., Theseira, W., Ko, G., & Khor, K. A. (2020). Evaluating human versus machine learning performance in classifying research abstracts. Scientometrics, 125(2), 1197–1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03614-2

Guerrero Bote, V. P., Olmeda-Gómez, C., & de Moya-Anegón, F. (2013). Quantifying the benefits of international scientific collaboration. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(2), 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22754

Haven, T. L., Bouter, L. M., Smulders, Y. M., & Tijdink, J. K. (2019). Perceived publication pressure in Amsterdam: Survey of all disciplinary fields and academic ranks. PLoS ONE, 14(6), e0217931. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217931

Hudson, R. (2008). Research ethics and integrity—The case for a holistic approach. Research Ethics, 4(4), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/174701610800400402

Isasi, R. (2012). Alliances, collaborations and consortia: The International Stem Cell Forum and its role in shaping global governance and policy. Regenerative Medicine, 7(6s), 84–88. https://doi.org/10.2217/rme.12.79

Javed, S. A., & Liu, S. (2018). Predicting the research output/growth of selected countries: Application of even GM (1, 1) and NDGM models. Scientometrics, 115(1), 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2586-5

Jiang, L. A., Zhu, N., Yang, Z., Xu, S., & Jun, M. (2018). The relationships between distance factors and international collaborative research outcomes: A bibliometric examination. Journal of Informetrics, 12(3), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.04.004

Khor, K. A., & Yu, L.-G. (2016). Influence of international co-authorship on the research citation impact of young universities. Scientometrics, 107(3), 1095–1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1905-6

Khor, K. A., Yu, L. G., & Soehartono, A. M. (2021). Detecting global publication trends in research integrity and research ethics (RIRE) through bibliometrics analysis. In 18th International Society of Scientometrics and Informetrics Conference (ISSI 2021) in Leuven, Belgium as a virtual event . https://issi2021.org/.

Leshner, A. I., & Turekian, V. (2009). Harmonizing global science. Science, 326(5959), 1459–1459. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1184624

Leydesdorff, L., & Wagner, C. S. (2008). International collaboration in science and the formation of a core group. Journal of Informetrics, 2(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2008.07.003

Li, J., Guo, K., Viedma, E. H., Lee, H., Liu, J., Zhong, N., Gomes, L. F. A. M., Filip, F. G., Fang, S.-C., Özdemir, M. S., Liu, X., Lu, G., & Shi, Y. (2020). Culture versus policy: More global collaboration to effectively combat COVID-19. The Innovation, 1(2), 100023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2020.100023

Lins, L., & Carvalho, F. M. (2014). Scientific integrity in Brazil. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 11(3), 283–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-014-9539-y

Mejlgaard, N., Bouter, L. M., Gaskell, G., Kavouras, P., Allum, N., Bendtsen, A. K., Charitidis, C. A., Claesen, N., Dierickx, K., Domaradzka, A., Elizondo, A. R., Foeger, N., Hiney, M., Kaltenbrunner, W., Labib, K., Marušić, A., Sørensen, M. P., Ravn, T., Ščepanović, R., … Veltri, G. A. (2020). Research integrity: Nine ways to move from talk to walk. Nature, 586(7829), 358–360. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02847-8

Michalek, A. M., Hutson, A. D., Wicher, C. P., & Trump, D. L. (2010). The costs and underappreciated consequences of research misconduct: A case study. PLoS Medicine, 7(8), e1000318. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000318

Moiwo, J. P., & Tao, F. (2013). The changing dynamics in citation index publication position China in a race with the USA for global leadership. Scientometrics, 95(3), 1031–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0846-y

Okonta, P. I., & Rossouw, T. (2014). Misconduct in research: A descriptive survey of attitudes, perceptions and associated factors in a developing country. BMC Medical Ethics, 15(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-15-25

Powell, J. J. W., Baker, D. P., & Fernandez, F. (2017). The century of science: The global triumph of the research university. International Perspectives on Education & Society. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-367920170000033003

Qiu, J. (2015). Safeguarding research integrity in China. National Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwv002

Resnik, D. B. (2020). What is ethics in research & why is it important? National institute of environmental health sciences. Retreived April 22, 2021, from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/bioethics/whatis/index.cfm

Rodrigues, M. L., Nimrichter, L., & Cordero, R. J. B. (2016). The benefits of scientific mobility and international collaboration. FEMS Microbiology Letters. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnw247

RoyalSociety. (2011). Knowledge, networks and nations. Reports.

Satalkar, P., & Shaw, D. (2019). How do researchers acquire and develop notions of research integrity? A qualitative study among biomedical researchers in Switzerland. BMC Medical Ethics, 20(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0410-x

Schüklenk, U. (2000). Protecting the vulnerable: Testing times for clinical research ethics. Social Science & Medicine, 51(6), 969–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00075-7

Shashnov, S., & Kotsemir, M. (2018). Research landscape of the BRICS countries: Current trends in research output, thematic structures of publications, and the relative influence of partners. Scientometrics, 117(2), 1115–1155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2883-7

Sponholz, G. (2000). Teaching scientific integrity and research ethics. Forensic Science International, 113(1–3), 511–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00267-X

Steen, R. G., Casadevall, A., & Fang, F. C. (2013). Why has the number of scientific retractions increased? PLoS ONE, 8(7), e68397. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068397

Stone, D. (2012). Transfer and translation of policy. Policy Studies, 33(6), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2012.695933

Titus, S. L., Wells, J. A., & Rhoades, L. J. (2008). Repairing research integrity. Nature, 453(7198), 980–982. https://doi.org/10.1038/453980a

Wagner, C. S., Park, H. W., & Leydesdorff, L. (2015). The continuing growth of global cooperation networks in research: A conundrum for national governments. PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0131816. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131816

Yi, N., Standaert, N., Nemery, B., & Dierickx, K. (2017). Research integrity in China: Precautions when searching the Chinese literature. Scientometrics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2191-z

Zeng, W., & Resnik, D. (2010). Research integrity in China: Problems and prospects. Developing World Bioethics. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8847.2009.00263.x

Zhang, L., Powell, J. J. W., & Baker, D. P. (2015). Exponential growth and the shifting global center of gravity of science production, 1900–2011. Change: the Magazine of Higher Learning, 47(4), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2015.1053777

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Ministry of Education Singapore AcRF Tier 1 Grant No. RG141/17. A previous version is part of the Proceedings of the 18th International Society of Scientometrics and Informetrics Conference (ISSI 2021) (Khor et al., 2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soehartono, A.M., Yu, L.G. & Khor, K.A. Essential signals in publication trends and collaboration patterns in global Research Integrity and Research Ethics (RIRE). Scientometrics 127, 7487–7497 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-022-04400-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-022-04400-y