Abstract

While private entrepreneurial activity has been at the core of entrepreneurship, nonprofit ventures still need to be explored in the literature. Using norm-activation theory (NAT) and resource-based view (RBV) lenses, we explore the antecedents of undertaking nonprofit entrepreneurial activity. By examining 8544 entrepreneurs’ decisions about the type of entrepreneurship to engage in, we find that not all human capital has a similar influence on people’s decisions regarding the types of formation of their venture. The results suggest that entrepreneurs' job-related experiences and social orientation are significantly linked to nonprofit entrepreneurship. The results of our study contribute to the human capital theory by demonstrating that people’s value influences how they use their knowledge resources.

Plain English Summary

A combination of work experience and social orientation is at the heart of the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship, not just social orientation.

Understanding the antecedent of engagement in nonprofit entrepreneurship is important since nonprofit organizations combine two competing organizational objectives – creating social values and economic wealth. The nonprofit sector presents an interesting alternative context since the financial incentive is crucial for engaging in entrepreneurial activity in the for-profit context. In this paper, we supplement the Resource-Based View (RBV) literature by incorporating human capital and the norm-activation theory (NAT) framework to investigate what influences an individual’s decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. This framework enables us to investigate the influence of the combination of resources in the possession of entrepreneurs and the values that are important to them are used to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

While private entrepreneurial activity has been at the core of entrepreneurship, nonprofit venturing is still scarce in the literature even though the entrepreneurial process for commercial, social, and nonprofit entrepreneurship follows a similar process from discovery and evaluation to exploitation and several in-between steps, such as the decision to launch the venture, assemble resources, and build a successful venture (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). One of the significant differences between for-profit, social entrepreneurship, and nonprofit enterprises seek to create social values (Costanzo et al., 2014; Defourny & Nyssens, 2008; Miller et al., 2012; Peredo & Mclean, 2006; Santos et al., 2015; Shaw & Carter, 2007).

The existing literature related to for-profit, nonprofit, and social entrepreneurship has examined how education level (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Germak & Robinson, 2014; Lehner & Germak, 2014; Ucbasaran et al., 2008); prior entrepreneurial experience (Ucbasaran et al., 2008); industry experience (Ucbasaran et al., 2008), psychological attributes (Carter et al., 2003), public service motivation (Germak & Robinson, 2014; Lehner & Germak, 2014), and demographic factors (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Robinson & Sexton, 1994; Ucbasaran et al., 2008) influence the decision to engage in entrepreneurial activity, both for-profit and nonprofit. Entrepreneurship literature has also examined how motivation (Shepherd et al., 2019; Germak & Robinson, 2014; Aileen & Mottiar, 2014; Christopoulos & Vogl, 2015) and autonomy (Hamilton, 2000) influence entrepreneurs' decisions to engage in entrepreneurship. While resources and personal preferences are important antecedents for engaging in entrepreneurial activity, a significant gap in the literature is how people decide to use their resources to align with their values and how that influences their decision to form a specific entity type. We address this question by examining whether an entrepreneur's social orientation affects their decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship and whether their human capital resources moderate this effect. These questions are essential for understanding the entrepreneur's motivation behind creating a new nonprofit venture. From a decision maker's perspective, these questions shed light on what factors influence an individual's decisions and values on their motivation to undertake the entrepreneurial activity with a more significant social impact or greater social benefit (ex., nonprofit) than personal benefit.

Nonprofit organizations contribute to society by solving social issues by providing collective or public goods that the market cannot offer profitably or by the government (Harrison & Seim, 2018) while also creating economic wealth for the organization (Mair and Marti, 2006; Tan et al., 2005). In addition to their commitment to social concerns, nonprofit organizations are also accountable to their diverse stakeholders, such as donors, board members, the local community, volunteers, employees, regulatory authorities, and managers (Morris et al., 2011; Salamon, 1992).

Various institutional and cultural factors influence people’s decision to engage in activities that address social concerns (Hechavarria et al., 2023; Stephan et al., 2015; Urbano et al., 2016). In addition to more significant societal influence, people’s interpersonal characteristics, such as social orientation, can be an essential motivator for an entrepreneur to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship since it can act as a trigger for compassion (Dees, 2007; Mair & Marti, 2006; Miller et al., 2012; Stephan et al., 2015) and prosocial behavior (Grant, 2008) can motivate entrepreneurs to engage in activity to solve a social ill or increase other's welfare (Dees, 2007; Fowler, 2000; Mair & Marti, 2006; Miller et al., 2012).

We test this paper's hypotheses by focusing on the norm-activation theory (NAT) and resource-based view (RBV) and using the Probit method to analyze the entrepreneurial decisions of 8544 entrepreneurs. We aim to understand how nonprofit entrepreneurs are different from what has already been established in the literature for for-profit entrepreneurs and whether the combination of knowledge resources of an entrepreneur and their value of social orientation influences the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. In doing so, we make two significant contributions to the literature. First, the RBV literature has been focused on the attributes of resources and combinations of resources that allow firms to gain a competitive advantage. Second, entrepreneurship literature recognizes the importance of resources in the decision to engage in entrepreneurship. However, the RBV literature has insufficiently investigated how combining knowledge resources under an individual's possession and their value associated with social orientation attracts decision-makers to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. Our results demonstrate that the availability of one’s resources and one’s value are not mutually exclusive. Instead, while social orientation is one of the significant components influencing the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship, resources also contribute to that decision.

Second, human capital theory is focused on the importance of knowledge resources to engage in entrepreneurial activity (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Ucbasaran et al., 2008), but it has insufficiently investigated how different types of experience can influence the knowledge capacity of an entrepreneur that may affect the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. Therefore, we empirically investigate how entrepreneurs’ industry and entrepreneurial experiences combined with social orientation may influence the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. Our results demonstrate how entrepreneurs' actions/behavior encompassing social orientation and job experience affect the 'value' they create by engaging in nonprofit entrepreneurship and helping judge which resources are essential in different contexts (Welter, 2011; Welter et al., 2019).

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we discuss the attributes of resources. In the following section, we develop hypotheses linking individuals' values, resources, and decisions to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. Then, we present our data and method, followed by the conclusion and discussion section.

2 Theory and hypotheses development

2.1 Nonprofit context

Entrepreneurs involved in nonprofit entrepreneurial activity go through a similar evolution of discovery, evaluation, and exploitation (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000) as for-profit entrepreneurs, “dreaming of things that do not yet exist, bringing them into creation and gaining market acceptance are perhaps the most mesmerizing of all entrepreneurial behaviors’ (Gaglio, 2004, p. 533). Nonprofit organizations are self-governed entities formed to fill a social need and promote social welfare (Ko & Liu, 2021; McDonald, 2007; Morris et al., 2021) or provide collective or public goods that the market cannot provide profitably or by the government (Farinha et al., 2020; Harrison & Seim, 2018). Therefore, rather than creating wealth for the founders/owners, serving social needs/purposes along with the sustainability of the organization are essential characteristics of nonprofit organizations (Aparicio et al., 2021; Austin et al., 2006; Ko & Liu, 2021; Moss et al., 2011).

Another critical distinction between for-profit and nonprofit organizations is the distribution of profit. While for-profit/market-based entrepreneurial motivation to undertake entrepreneurship is often profit-making (Estrin et al., 2013; Ko & Liu, 2021) or personal benefit (e.g., necessity opportunity) (Estrin et al., 2013; Shepherd et al., 2019) enjoying the reward of their entrepreneurial activity, in the end, nonprofit organizations do not distribute their revenue surplus to shareholders or members (Boris & Steuerle, 2006; Salamon, 1992). Consequently, nonprofit organizations' profit motive is sustainability, progressing toward their social purpose, and providing value to multiple stakeholders (Austin et al., 2006). Nonprofit organizations must also be concerned about their stakeholders, such as donors, board members, the local community, volunteers, employees, regulatory authorities, managers, etc. (Morris et al., 2011; Salamon, 1992). Their sources of funding are also different from those of for-profit organizations. Nonprofit organizations invest a significant amount of their resources in fund-raising processes. Many nonprofit organizations also have gift shops and concerts that can generate profit for these organizations (Dees, 2007).

Nonprofit entrepreneurship also shares some similarities with public entrepreneurship, providing services for the benefit of society by exploiting opportunities (Demircioglu & Chowdhury, 2021; Hayter et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2013). However, these organizations also have differences concerning their source of funding resources. Since public organizations receive funding from fees and taxes, public entrepreneurs will engage in entrepreneurial activity by providing services that will help to increase or diversify their funding streams (Perkmann, 2007, p. 867). Additionally, engagement in public entrepreneurship is motivated by gaining autonomy for their organization and less uncertainty (Carpenter and Fredrickson, 2001; Klein et al., 2010; Lowndes, 2005).

2.2 Linking values with resources

According to norm-activation theory (NAT), personal norms and values dictate a person’s pro-social behavior, such as engagement in altruistic behavior (Schwartz and Clausen, 1970, 1975, 1977; Schwartz & Howard, 1984; Caprara et al., 2012), and promotion of sustainable behavior (Black et al., 1985; Lind et al., 2015), etc. Personal values are “a desirable trans situational goal varying in importance, which serves as a guiding principle in the life of a person or other social entity” (Schwartz, 1992, p. 21). Prosocial behavior denotes an individual who engages in involuntary action that benefits others (Batson, 1998; Eisenberg, 2006; Penner et al., 2005). Personal values influence pro-social behavior since values reflect a general belief about someone’s priorities in life (Caprara et al., 2012; Schwartz, 1992), awareness of need (Vining & Ebreo, 1992) along with self-efficacy and locus of control (Bandura, 1997; Rauch & Frese, 2007).

Resources are essential to firms, and the existing literature has examined how and why specific resources can become a source of competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Peteraf, 1993; Wernerfelt, 1984). The knowledge endowment can help define a firm’s capacity to translate the firm’s resources from inputs into output (Arrow & Hahn, 1971; Debreu, 1959; Nelson & Winter, 1982, p. 59). Similar to established firms, resources in possession of an entrepreneur can be an important motivating factor, and an individual’s motivation to engage in entrepreneurial activity may depend on the assessment of resources in possession and human capital resources in possession of entrepreneurs can be a critical resource for identifying and exploiting an opportunity (Becker, 1964; Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Gibbons & Waldman, 2004).

Entrepreneurs are the primary repository of knowledge resources that are important and valuable (Alvarez & Busenitz, 2001; Cooper et al., 1995; Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Gifford, 1993; Wright et al., 1997). Knowledge resources in possession of entrepreneurs can be obtained from various sources –- formal education, on-the-job, continuing education training during the job tenure, etc. (Marvel et al., 2016; Sallis & Jones, 2002; Ucbasaran et al., 2008). Additionally, the transferability of knowledge is another source of knowledge for individuals. An individual’s knowledge and skills gained in one industry can help to identify and exploit an opportunity in another sector (Neffke & Henning, 2013); in this case, an individual who gained knowledge in the for-profit or government sector can apply the knowledge to identify and exploit the opportunity and engage in nonprofit entrepreneurial activity. In addition to resources, people also have values learned from different sources, such as family and social norms. These values also change over time as people transition through various stages of their lives and the experiences they have lived through. People’s decisions to engage in activities are influenced by the values that are important to them and the resources they possess.

2.3 Social orientation and nonprofit entrepreneurship

Similar to for-profit firms, entrepreneurial activity in the nonprofit context involves opportunity identification, “future situation deemed both desirable and feasible” (Stevenson & Jarillo, 1990; p. 23), desirability to exploit the opportunity (Tumasjan et al., 2013), feasibility (Tumasjan et al., 2013), and motivation (Shane et al., 2003) to engage in entrepreneurial activity. Entrepreneurial activity in the nonprofit sector tends to be “…. embedded with social purpose” (Austin et al., 2006, p. 1). Entrepreneurs involved in nonprofit entrepreneurship activity are ideologically motivated, aware of societal problems, and passionate about finding solutions to problems (Frank, 2002; James, 2003; Miller, 1998; Young, 1986). Nonprofit entrepreneurs are knowledgeable about the problem, so they can better identify and exploit the opportunity. In addition, finding innovative solutions to solve social problems is essential for them; as suggested by Miller (1998), “…. closeness to the problem can lead to new insights and innovative solutions that might be missed by larger, more established organizations whose leaders have lost touch with the grassroots” (p. 95). Individuals in the government sector, acting as government agents, can also engage in social entrepreneurship that creates social values through their agencies (Leyden, 2016; Morris et al., 2021; Shockley et al., 2006).

Individuals play an essential role in generating entrepreneurship, but the characteristics of entrepreneurs vary (Morris et al., 2011, 2021; Ruebottom, 2013). When it comes to the social-oriented characteristics of people, nonprofit entrepreneurs exhibit unique characteristics. Societies that have a high level of social progress orientation consist of people who are engaged in civic activism, concerned with interpersonal safety and trust, gender equality, the inclusion of minorities, and involved in local clubs and associations (Aparicio et al., 2021; Urbano et al., 2016). Prosocial behavior is an essential characteristic of individuals engaged in nonprofit entrepreneurship because not only are they engaged in voluntary activities such as donating, but they also are contributing their time along with their personal resources, such as experience, bringing together employees, volunteers, for the greater benefit of society in the process (Pinillos & Reyes, 2011; Ruebottom, 2013). For instance, Wamuchiru and Moulaert’s (2018) study shows that social entrepreneurs providing services like water and sanitation to marginalized communities also help create new institutions. By engaging in social entrepreneurship, they also respond to their motivation, such as the need for achievement and an opportunity to match their personal value/social orientation and their resources, or what Besley and Ghatak (2005) characterize as “mission matching” and “value congruence.” Individuals engaged in nonprofit entrepreneurship view the opportunity to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship as “a means to the end goal of benefiting others” (Grant, 2008, p. 49). Therefore, an entrepreneur’s values and prosocial orientations are essential for engagement in nonprofit entrepreneurial activity.

In addition to the awareness of social need, nonprofit entrepreneurs believe that he/she has the ability to contribute to the need or alleviate the problem. Entrepreneurs also have their motivations, such as an individual’s need for achievement (Shane et al., 2003), risk-taking (Shane et al., 2003), tolerance for ambiguity (Shane et al., 2003), locus of control (Rauch & Frese, 2007) and self-efficacy (Rauch & Frese, 2007). Nonprofit entrepreneurship allows an individual to combine their personal norms, knowledge of social needs, identifying actions necessary to solve the need, and feelings of responsibility “…situation-specific reflections of the cognitive and affective implications of a person’s values for specific actions” (p. 199). Therefore, we hypothesize that,

-

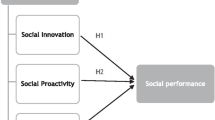

Hypothesis 1: An entrepreneur’s social orientation will positively influence nonprofit entrepreneurship formation decisions.

2.4 Linking knowledge resources and social orientation to nonprofit entrepreneurship

Nonprofits are unique organizations where entrepreneurs are often viewed as motivated by their ideology, motivation to contribute to their community, and passion for the organization's mission (Carman and Nesbit, 2013; Frank, 2002; James, 2003). Similar to other organizations, existing nonprofit literature suggests that leaders significantly influence the organization. In some instances, nonprofit organizations suffer from the founder’s syndrome, where the founding leader exerts too much influence on the organization (Block & Rosenberg, 2002). Nonprofit organizations tend to fill an essential gap in society where governments, markets, contracts, and expressive purposes failed (Eckerd & Moulton, 2011; Handy et al., 2007; Knutsen & Brower, 2010; Salamon & Sokolowski, 2001). Regardless of the reasons or purpose of the organization, entrepreneurs’ resources contribute significantly to these organizations.

A combination of social orientation and possession of knowledge resources can be a perfect mix for engaging in nonprofit entrepreneurship. People with high social orientation are likely to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship since it allows people to identify social needs and encourages people to engage in social-oriented activities (Aparicio et al., 2021; Bauernschuster et al., 2010; Urbano et al., 2016). Nonprofit entrepreneurship requires entrepreneurs to bring together multiple resources (i.e., volunteers, employees, stakeholders) to develop an organization that can address a social concern. Individuals with a high level of knowledge resources are also likely to have access to other resources since they have developed their social networks, problem-solving skills, and emotional intelligence over the years (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; De Clercq et al., 2018; Schulz & Baumgartner, 2013).

As people contemplate the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship, they need to think about the organization's mission and vision, develop sound organizational strategies, a responsive board of directors, internal processes, managerial oversights, and a robust financial resource base that are necessary for engaging in entrepreneurship (Chambré & Fatt, 2002; Frank, 2002; Grant & Crutchfield, 2008; Nitterhouse, 1997; Strichman et al., 2008). These factors contribute to the organization's success in the short- and long-run. People with high knowledge resources gathered from education and industry experiences will be able to develop these resources by themselves or with the help of others. Additionally, people with high knowledge resources are likely to have a high level of locus of control that helps them deal with challenges as they engage in entrepreneurship. Locus of control is important for individuals interested in engaging in entrepreneurial activity since they tend to believe that their actions will help achieve the desired results (Rauch & Frese, 2007; Solcová & Kebza, 2005). Therefore, people with high levels of social orientation and knowledge resources will help develop the resources necessary to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship.

Individuals thinking about engaging in nonprofit organizations are likely to think about the organization’s future when the organization is transitioning through different phases of its lifecycle (Light, 2004). The lifecycle stages require different resources. Individuals with high knowledge resources tend to have high self-efficacy regarding their ability to achieve their goals. A combination of self-efficacy due to a high level of knowledge of resources and social orientation (Caprara & Steca, 2005; Caprara et al., 2012) will motivate an individual to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship.

-

Hypothesis 2: The entrepreneur’s social orientation will have a stronger positive relationship with nonprofit entrepreneurship formation decisions with high knowledge resources than low knowledge resources.

2.5 Opportunity-related experience, social orientation, and nonprofit entrepreneurship

Prior entrepreneurial experience can be an essential resource for entrepreneurs that constitutes knowledge relatedness, where the degree to which existing knowledge possessed by the individual is related to the opportunity an individual is interested in exploiting (Wood & Pearson, 2009). Entrepreneurs with prior entrepreneurial experience possess knowledge about the identification of opportunities along with various processes associated with start-ups (Bates, 2005; Brüderl et al., 1992; Carter et al., 1997; Coleman et al., 2013; Cooper et al., 1994; Van Praag, 2003). Individuals with a high level of social orientation can combine their resources, entrepreneurial experience, and social orientation to search for and exploit nonprofit entrepreneurship.

Identifying an opportunity may not always translate to an action if an individual is unwilling to act on that. In order to act on that, an individual needs to be able to accept the uncertainty associated with entrepreneurial engagement. Individuals with prior entrepreneurial experience can leverage tolerance for decision uncertainty and make decisions on a hunch when there is a lack of information in certain instances (Allinson et al., 2000). Individuals with opportunity identification ability, social orientation, and decision-making ability have a “strategic asset” (Markides & Williamson, 1996, p. 340) that can benefit greater society and are more likely to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurial activity.

Similar to for-profit organizations, nonprofit organizations need funding to achieve their objective but face funding-related challenges (Calic & Mosakowski, 2016). Individuals with prior entrepreneurial experience are likely to have gained experiences related to soft skills and information, as well as access to external sources of financing (Westhead & Wright, 1998), all of which help with individual’s self-efficacy related to getting funding for their potential organization. Information sources can help to alleviate frustration and save time during the early stages of the start-up process when nascent organizations lack the legitimacy necessary for obtaining resources. Entrepreneurs with social orientation with such resources will likely have an edge (Bolzani et al., 2019; Cooper et al., 1995; Dimov, 2010; Hardy & Maguire, 2017; Zietsma & Lawrence, 2010) than their counterparts who lack these resources.

Soft skills are associated with communication, presentation, writing, etc., which are valuable skills for getting volunteers or the organization's financial resources. Individuals with entrepreneurial experience are likely to have well-developed skills since they are likely to have used these resources during their experiences. Individuals with soft skills and social orientation and can effectively present social issues to potential donors, appeal/market their products/services to their customers (Chatterji, 2009), and bring diverse stakeholders together to access resources (Maguire et al., 2004). Therefore, opportunity-related knowledge resources and social orientation are essential for recognizing and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities (Hayek, 1945; Haynie et al., 2009; Prahalad & Hamel, 1994; Venkataraman, 1997). Therefore, we hypothesize that,

-

Hypothesis 3: The entrepreneur’s social orientation will have a stronger positive relationship with nonprofit entrepreneurship formation with high opportunity-related experience than with low opportunity-related experience.

3 Method

3.1 Data and sample

We collected data from the Entrepreneurship Development Program (EDP) of Emory University. The Global Accelerator Learning Initiative (GALI) at Emory University worked with accelerator programs across countries to gather detailed information about the founders during the application process. The sample consisted of 13844 new ventures participating in the accelerator programs from 2013 to 2017. We only included ventures with one founder and firms less than ten years old (Islam et al., 2018). After excluding the team-based start-ups, our final sample included 8544 firms with one entrepreneur, so our analysis included 8544 entrepreneurs, so the unit of analysis is at the individual level.

3.2 Dependent variable

Our dependent variable is nonprofit entrepreneurship. In the survey, the respondents answered the question about the legal status of the venture. Respondents identified the legal status of their ventures from the following options –- 1) Nonprofit, 2) For-profit company, 3) Undecided, 4) other. We coded the legal status of the ventures as 1 = Nonprofit, 0 = all other types.

3.3 Independent variables

To measure the social orientation of the ventures, we have included the following survey question: Does your venture have the explicit intent of creating social or environmental impacts? (Yes = 1, No = 0). Individuals' motivation and information about social issues are important for engaging in nonprofit entrepreneurship (Miller, 1998).

We included several indicators to measure knowledge resources –- levels of education, experience in different sectors (for-profit, nonprofit, government), positions held in these organizations, and tenure. Consistent with existing research, we included the level of education and various measures for work-related experiences (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Ucbasaran et al., 2008). The education of the founder was represented by formal education. We coded: 1 = high school; 2 = technical or vocational degree; 3 = bachelor's degree and higher. The sector-specific experience was measured by whether the founder worked in a for-profit, nonprofit, or government organization; we created three dummy variables. The industry-specific experience was measured by the type of position the founder held during their first and second job tenure. We coded the variables based on the following classifications: 1 = Other; 2 = Support Staff; 3 = Senior Management; and 4 = CEO/Executive Director. The founder’s job tenure was measured by the responses to the question: How long were you at this job? People responded by identifying the length of their tenure at their first and second jobs.

The founder’s entrepreneurial experience measured the opportunity-related experience. Individuals with prior entrepreneurial experience are likely to recognize and exploit opportunities (Dimov, 2010; Ucbasaran et al., 2008). Respondents answered the following questions: 1) How many for-profit organizations were launched by the founder before launching this venture? 2) How many nonprofit organizations were launched by the founder before launching this venture?

3.4 Control variables

We have included several firms and the founder characteristics as control variables. Firm-level controls include the firm’s age and size. Firm age was calculated by subtracting the year the venture was founded from the year the survey was conducted. Survey respondents answered, “In what year was your venture founded.” Firm size was measured by the number of full-time employees currently working in the venture. Survey respondents identified the sector they operate in from a list of preidentified industry sectors. This list includes the following industry sectors: Agriculture, Artisanal, Culture, Education, Energy, Environment, Financial Services, Health, Housing development, Information and Communication Technology, Infrastructure/facilities development, Supply chain services, Technical assistance services, Tourism, Water, and Others.

The founder’s characteristics included information about the founder’s gender and age. We coded the founder’s gender as Female = 1 and Male = 2. Founder’s mean age is about 35.

A detailed description of all the variables included in this article is listed in Table 1. Table 2 presents the correlation coefficients of all the variables. The first job in a for-profit and the first job in a nonprofit are highly correlated. To alleviate the multicollinearity concerns, we also examined the variance inflation factor (VIF); none of the variables have a VIF above 10. First-job tenure, second-job tenure, and age have correlation coefficients of 0.55 and 0.52, respectively.

4 Empirical technique

Our dependent variable has the values of 1 and 0. We used a probit specification based on our dependent variable since OLS estimation would yield biased and inconsistent estimations (Bowen & Wiersema, 2004; Greene, 2012; Long, 1997). We used the Huber/White/sandwich estimator of variance and vce(robust) for robust standard errors. The coefficient estimates were calculated based on the maximum likelihood method. Tables 3 and 4 include several ‘fit’ statistics. Chi-square presents the significance level of all the variables in the model, and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) shows the preference of the models.

5 Results

Tables 3 and 4 present the results of our Probit regression estimation. Table 3 presents results for direct effects, and Table 4 presents results for interaction effects. In hypothesis 1, we posited that social orientation would positively affect the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship formation. We find support for our hypotheses presented in Model 2 (β = 0.58, p < 0.1) and Model 13 (β = 0.47, p < 0.1) in Table 3. Additionally, Model 14 in Table 4, which shows results for the relationship between social orientation and nonprofit, supports our hypothesis 1 (β = 4.5, p < 0.1). The relationship is consistent across all models in Table 4. These results align with the existing studies that suggest that people with high levels of social orientation are likely to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship (Aparicio et al., 2021; Morris et al., 2021; Urbano et al., 2016) and support our hypothesis 1. The results suggest that people with high social orientation values are likely to use it to address social concerns by engaging in nonprofit entrepreneurship.

In hypothesis 2, we posited that knowledge resources will strengthen the positive relationship between social orientation and nonprofit entrepreneurship. We used several indicators for knowledge resources (Davidsson & Honig, 2003). We found conflicting results related to the relationship between knowledge resources and their influence on social orientation and nonprofit entrepreneurship in different models and in direct and interaction effects; results are presented in Table 2 and 2, respectively. In the direct effect relationship, all formal education acquired through primary, vocational and secondary, and tertiary has a positive relationship with undertaking nonprofit entrepreneurship. Individuals in top management positions are more likely to undertake nonprofit entrepreneurship (β = 0.25, p < 0.1). All of these results suggest that human capital plays an important role in people’s decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship, which is aligned with the existing literature (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; De Clercq et al., 2018; Schulz & Baumgartner, 2013).

Contrary to the existing study, tenure at a job does not have a significant relationship with engagement in nonprofit entrepreneurship. However, consistent with the current literature, individuals with work experience in the nonprofit sector are more likely to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship than individuals in for-profit or government sectors. The result is aligned with the existing literature (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Rauch & Frese, 2007; Solcová & Kebza, 2005). The interaction relationship between different types of knowledge resources, social orientation, and nonprofit entrepreneurship shows conflicting results. The interactive relationship between formal education, individual positions they held in their jobs, and social orientation do not have any significant relationship with nonprofit entrepreneurship, which is the reverse of the direct relationship that we found. The results suggest that as people gather their human capital, their economic benefits become essential, which can undermine their social orientation. With regards to one’s tenure in one’s job, our direct effect results change. In the interaction results, tenure in their most recent jobs, social orientation, and nonprofit entrepreneurship have a positive and significant relationship (β = 0.05, p < 0.1, Model 5 and β = 0.06, p < 0.05, Model 14, Table 2), suggesting that as people increase their depth of knowledge through work experience, they use their knowledge and social orientation to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. These results complement the existing results by suggesting that in addition to the breadth of knowledge, depth of knowledge is also important for entrepreneurs (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; De Clercq et al., 2018; Schulz & Baumgartner, 2013).

In hypothesis 3, we posited that high opportunity-related experience and social orientation will positively affect nonprofit entrepreneurship formation. Contrary to the existing research focusing on for-profit entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial experience related to for-profit and nonprofit and social motivation does not have a positive or significant relationship with nonprofit entrepreneurship (Bolzani et al., 2019; Coleman et al., 2013). This result suggests that social orientation is not a strong motivating factor for an individual to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship once they have experienced the challenges associated with entrepreneurship. Table 5 presents our original hypotheses and results. Table 6 presents the marginal effect results.

6 Discussion

In this paper, we examine whether (or not) people’s social orientation influences their decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. In addition, we examine the influence of their knowledge resources and opportunity-related experience on their decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship when they have high social orientation. The results of our study show that people’s social orientation positively influences one’s decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. Regarding the influence of knowledge resources, we find conflicting results. We find that the combination of social orientation, formal education, and different types of job roles do not have a significant relationship with nonprofit entrepreneurship, but the combination of social orientation with job tenure does. Besides, we also find that one’s opportunity-related experience and social orientation do not significantly influence the relationship.

6.1 Theoretical contributions

Studies have begun to identify that the contribution of resources to entrepreneurship varies by context and is an essential component of entrepreneurship (Marvel et al., 2016; Welter et al., 2019). Our study demonstrates that while knowledge resources endowment is important for nonprofit entrepreneurship, not all types of knowledge resources have the same effect. Individuals may possess the same level of education or have similar work experience, but the transferability or product of the knowledge resource may not be similar (Marvel et al., 2016; Unger et al., 2011).

The job tenure and social orientation results suggest that entrepreneurs are likely to be driven by a ‘taste of variety’ (Åstebro and Thompson, 2011). Engagement in entrepreneurship activity involves a range of activities. Long tenure in an organization enables an individual to gain broad functional skills. The breadth of job functions enables an individual to accumulate an array of skills that can be valuable for engagement in nonprofit entrepreneurship when people decide to combine their knowledge resources with their social orientation. Broad functional experience allows entrepreneurs to reduce the cost of accessing resources since their experience allows them to perform many required tasks independently. Nonprofit entrepreneurs can combine social orientation with their taste for doing many different things.

Tenure in a job allows an individual to gain in-depth knowledge. These individuals have more firm-specific capabilities and are often idiosyncratically well-matched with their current organization. These individuals are less mobile and less likely to move to another organization. The transferability of knowledge may take longer to develop, as suggested by the results related to job tenure. Therefore, people who realize that their knowledge is only confined to their current organization are likely to combine their social orientation with their knowledge to pursue their socially motivated interests by pursuing nonprofit entrepreneurial opportunities, as those might be more meaningful to them,

6.2 RBV in nonprofit context perspective

In this article, we used NAT and RBV to investigate factors influencing an individual’s decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. Our study provides insight into what Conner (1991) named ‘entrepreneurial vision and intuition,’ what Barney (1991) suggested gives a firm its competitive advantage, and what Alvarez and Busenitz (2001, p. 755) suggested to be central for recognizing “new opportunities and the assembling of resources for the venture” and how resources have different impact in a different context. Resources are important for new ventures to gain legitimacy and to gain competitive advantage, but an individual’s personal values can influence when and what types of opportunities an individual is willing to exploit and how an entrepreneur decides to combine resources.

Furthermore, we found that tenure at an organization combined with social orientation significantly explains an individual’s likelihood of engaging in nonprofit entrepreneurship. We controlled for entrepreneurs and found that it did not significantly explain the variance in entrepreneurs’ likelihood of engaging in nonprofit entrepreneurship; we still believe that more fine-grained investigations of age, gender, and nonprofit entrepreneurship have considerable potential. For example, Lévesque and Minniti (2011) suggested that societies with populations “excessively skewed toward old or young cohorts” are experiencing low levels of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial activity is not only good for the economic condition of a society (Braunerhjelm et al., 2010; Minniti & Lévesque, 2010), but it also contributes to government and market failure experienced by many emerging and developing countries. Further research may want to explore the role of age, demographic structure, and socioeconomic incentives in influencing the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurial activity.

Our findings support Kor et al. (2007) and Penrose’s (1959) argument regarding the versatility of personal knowledge and heterogeneity of entrepreneurial activity. An individual’s knowledge originates from various sources, and her job experience tends to have the largest impact on her knowledge since the organizations where the individual spends a significant portion of her lifespan influence an employee’s mobility and other career outcomes (Castilla, 2008; Petersen & Saporta, 2004). Employers' characteristics influence an individual’s decision to engage in entrepreneurship because many individuals spend a large portion of their time in established organizations, transitioning through various positions. Once they reach the epitome of their career, they have limited advancement opportunities (Sørensen & Sharkey, 2014, p. 329). Engagement in nonprofit entrepreneurship gives them an opportunity to combine their social orientation and organizational knowledge, such as how an organization should be structured, how an organization should act, etc. (Baron et al., 1999; Burton & Beckman, 2007; Eesley et al., 2014).

7 Conclusion

In this study, we examine what factors influence an individual’s decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship to provide insight into how an individual’s knowledge resources and social orientation have a differential impact in a context different from for-profit entrepreneurship. We believe that our findings have important implications for future research that is focused on understanding motivation along with applying resource-based theories to a different context.

Amongst several contributions, we believe that integrating RBV and NAT theories in the nonprofit context represents an important step toward understanding why an individual would choose to exploit a nonprofit opportunity. NAT theorists have argued that an individual’s norms and values dictate behavior. RBV theorists have argued that existing resources combined with new resources give firms a competitive advantage (Penrose, 1959). The results of our study suggest that the combination of an individual’s knowledge resources and social orientation influences their decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship.

8 Limitations and future research directions

This article is not without its limitations. In this paper, we have included educational background, various roles that founders held, types of organizations they worked in, and different types of entrepreneurial experiences as endowments of knowledge resources. Our study did not take into account how the career stages of an individual influence the use of these resources. Knowledge resource development, use of these resources, and career stages have a dynamic relationship. As individuals transition through various stages of their careers, they develop different types of resources while their responsibilities and personal needs also change. Future research could examine the relationship between these resources, career stages, and the decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship.

In this study, we have included individual-level factors that influence an individual’s decision to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. While individual-level components are important, contexts greatly influence people’s decisions as well. Future researchers can examine how country-level factors influence an individual’s decisions to engage in nonprofit entrepreneurship. Formal institutions, informal institutions, and resources influence how people make sense of their environment and the types of activities they want to engage in.

References

Aileen Boluk, K., & Mottiar, Z. (2014). Motivations of social entrepreneurs: Blurring the social contribution and profits dichotomy. Social Enterprise Journal, 10(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-01-2013-0001

Allinson, C. W., Chell, E., & Hayes, J. (2000). Intuition and entrepreneurial behaviour. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 9(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943200398049

Alvarez, S. A., & Busenitz, L. W. (2001). The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of Management, 27(6), 755–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(01)00122-2

Aparicio, S., Audretsch, D., & Urbano, D. (2021). Does entrepreneurship matter for inclusive growth? The role of social progress orientation. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 11(4), 20190308.

Arrow, K. J., & Hahn, E. H. (1971). General Competitive Analysis. Holden-Day.

Åstebro, T., & Thompson, P. (2011). Entrepreneurs, Jacks of all trades or Hobos? Research Policy, 40(5), 637–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.01.010

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 1–22.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baron, J.N., Hannan, M.T. & Burton, M.D. (1999). Building the iron cage: Determinants of managerial intensity in the early years of organizations. American Sociological Review, 527–547. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657254

Bates, T. (2005). Analysis of young, small firms that have closed: Delineating successful from unsuccessful closures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(3), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.003

Batson, C. D. (1998). Altruism and prosocial behavior. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 282–316). McGraw-Hill.

Bauernschuster, S., Falck, O., & Heblich, S. (2010). Social capital access and entrepreneurship. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76(3), 821–833.

Becker, G. (1964). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Emphasis on Education. Columbia University Press.

Brüderl, J., Preisendörfer, P., & Ziegler, R. (1992). Survival chances of newly founded business organizations. American Sociological Review, 57(2), 227–242.

Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2005). Competition and incentives with motivated agents. American Economic Review, 95(3), 616–636. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828054201413

Black, J. S., Stern, P. C., & Elworth, J. T. (1985). Personal and contextual influences on household energy adaptations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.70.1.3

Block, S. R., & Rosenberg, S. (2002). Toward an understanding of founder’s syndrome: An assessment of power and privilege among founders of nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 12(4), 353–368.

Bolzani, D., Fini, R., Napolitano, S., & Toschi, L. (2019). Entrepreneurial teams: An input-process-outcome framework. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 15(2), 56–258.

Boris, E. T., & Steuerle, C. E. (2006). Scope and dimensions of the nonprofit sector. In W. W. Powell & R. Sternberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector: A research handbook (2nd ed., pp. 66–88). Yale University Press.

Bowen, H. P., & Wiersema, M. F. (2004). Modeling limited dependent variables: Methods and guidelines for researchers in strategic management. In Research methodology in strategy and management (Vol. 1, pp. 87–134). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Braunerhjelm, P., Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2010). The missing link: Knowledge diffusion and entrepreneurship in endogenous growth. Small Business Economics, 34(2), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9235-1

Burton, M. D., & Beckman, C. M. (2007). Leaving a legacy: Position imprints and successor turnover in young firms. American Sociological Review, 72(2), 239–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240707200206

Calic, G., & Mosakowski, E. (2016). Kicking off social entrepreneurship: How a sustainability orientation influences crowdfunding success. Journal of Management Studies, 53(5), 738–767.

Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., & Eisenberg, N. (2012). Prosociality: The contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1289. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025626

Caprara, G. V., & Steca, P. (2005). Self–efficacy beliefs as determinants of prosocial behavior conducive to life satisfaction across ages. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(2), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.24.2.191.62271

Carman, J. G., & Nesbit, R. (2013). Founding new nonprofit organizations: Syndrome or symptom? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(3), 603–621.

Carpenter, M. A., & Fredrickson, J. W. (2001). Top management teams, global strategic posture, and the moderating role of uncertainty. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 533–545.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., & Gatewood, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39.

Carter, N. M., Williams, M., & Reynolds, P. D. (1997). Discontinuance among new firms in retail: The influence of initial resources, strategy, and gender. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(2), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(96)00033-X

Castilla, E. J. (2008). Gender, race, and meritocracy in organizational careers. American Journal of Sociology, 113(6), 1479–1526. https://doi.org/10.1086/588738

Chambré, S. M., & Fatt, N. (2002). Beyond the liability of newness: Nonprofit organizations in an emerging policy domain. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31(4), 502–524.

Chatterji, A. K. (2009). Spawned with a Silver Spoon? Entrepreneurial Performance and Innovation in the Medical Device Industry. Strategic Management Journal, 30(2), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.729

Christopoulos, D., & Vogl, S. (2015). The motivation of social entrepreneurs: The roles, agendas and relations of altruistic economic actors. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 6(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2014.954254

Coleman, S., Cotei, C., & Farhat, J. (2013). A resource-based view of new firm survival: new perspectives on the role of industry and exit route. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 18(01), 1350002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946713500027

Cooper, A. C., Folta, T. B., & Woo, C. (1995). Entrepreneurial information search. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)00022-M

Cooper, A. C., Gimeno-Gascon, F. J., & Woo, C. Y. (1994). Initial human and financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(5), 371–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)90013-2

Costanzo, L. A., Vurro, C., Foster, D., Servato, F., & Perrini, F. (2014). Dual-mission management in social entrepreneurship: Qualitative evidence from social firms in the United Kingdom. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(4), 655–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12128

Conner, K. R. (1991). A historical comparison of resource-based theory and five schools of thought within industrial organization economics: do we have a new theory of the firm? Journal of management, 17(1), 121-154.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

Debreu, G. (1959). Theory of Value. Wiley.

De Clercq, D., Thongpapanl, N., & Voronov, M. (2018). Sustainability in the face of institutional adversity: Market turbulence, network embeddedness, and innovative orientation. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 437–455.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2008). Social enterprise in Europe: Recent trends and developments. Social Enterprise Journal, 4(3), 202–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508610810922703

Dees, J. G. (2007). Taking Social Entrepreneurship Seriously. Society-New Brunswick, 44(3), 24.

Demircioglu, M. A., & Chowdhury, F. (2021). Entrepreneurship in public organizations: The role of leadership behavior. Small Business Economics, 57, 1107–1123.

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35, 1504–1512. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.12.1504

Dimov, D. (2010). Nascent entrepreneurs and venture emergence: Opportunity confidence, human capital, and early planning. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1123–1153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00874.x

Eckerd, A., & Moulton, S. (2011). Heterogeneous roles and heterogeneous practices: Understanding the adoption and uses of nonprofit performance evaluations. American Journal of Evaluation, 32(1), 98–117.

Eesley, C. E., Hsu, D. H., & Roberts, E. B. (2014). The contingent effects of top management teams on venture performance: Aligning founding team composition with innovation strategy and commercialization environment. Strategic Management Journal, 35(12), 1798–1817. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2183

Eisenberg, N. (2006). Prosocial Behavior. In G.G. Bear & K.M. Minke (Eds.), Children's needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention (pp. 313–324). National Association of School Psychologists.

Eisenhardt, K., & Martin, J. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11%3c1105::AID-SMJ133%3e3.0.CO;2-E

Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Stephan, U. (2013). Entrepreneurship, social capital, and institutions: Social and commercial entrepreneurship across nations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(3), 479–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12019

Farinha, L., Sebastião, J. R., Sampaio, C., & Lopes, J. (2020). Social innovation and social entrepreneurship: Discovering origins, exploring current and future trends. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 17, 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-020-00243-6

Fowler, A. (2000). NGDOs as a moment in history: Beyond aid to social entrepreneurship or civic innovation? Third World Quarterly, 21(4), 637–654.

Frank, P. M. (2002). Non-profit versus for-profit entrepreneurship: An institutional analysis. Alexandria, VA: Donors Trust. https://www.conversationsonphilanthropy.org/wp-content/uploads/frank.pdf

Gaglio, C. M. (2004). The role of mental simulations and counterfactual thinking in the opportunity identification process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(6), 533–552.

Germak, A. J., & Robinson, J. A. (2014). Exploring the motivation of nascent social entrepreneurs. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 5(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2013.820781

Gibbons, R., & Waldman, M. (2004). Task-specific human capital. American Economic Review, 94(2), 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041301579

Gifford, S. (1993). Heterogeneous ability, career choice and firm size. Small Business Economics, 5(4), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01516246

Grant, H. M., & Crutchfield, L. (2008). The hub of leadership: Lessons from the social sector. Leader to Leader, 2008(48), 45–52.

Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.48

Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric Analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631. https://doi.org/10.1086/262131

Handy, F., Mook, L., Ginieniewicz, J., & Quarter, J. (2007). The moral high ground: Differentials among executive directors of Canadian nonprofits.

Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2017). Institutional entrepreneurship and change in fields. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, 2, 261–280.

Harrison, T. D., & Seim, K. (2018). Nonprofit Tax Exemptions, For-profit Competition and Spillovers to Community Services. The Economic Journal, 129(620), 1817–1862. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12615

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530.

Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D. A., & McMullen, J. S. (2009). An opportunity for me? The role of resources in opportunity evaluation decisions. Journal of Management Studies, 46(3), 337–361.

Hayter, C. S., Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2018). Public-sector entrepreneurship. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34(4), 676–694.

Hechavarría, D. M., Brieger, S. A., Levasseur, L., & Terjesen, S. A. (2023). Cross-cultural implications of linguistic future time reference and institutional uncertainty on social entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 17(1), 61–94.

Islam, M., Fremeth, A., & Marcus, A. (2018). Signaling by early stage startups: US government research grants and venture capital funding. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.10.001

James, E. (2003). Commercialism and the mission of nonprofits. Society, 40(4), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-003-1015-y

Klein, P. G., Mahoney, J. T., McGahan, A. M., & Pitelis, C. N. (2013). Capabilities and strategic entrepreneurship in public organizations. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(1), 70–91.

Klein, P. G., Mahoney, J. T., McGahan, A. M., & Pitelis, C. N. (2010). Toward a theory of public entrepreneurship. European Management Review, 7(1), 1–15.

Knutsen, W., & Brower, R. S. (2010). Managing expressive and instrumental accountabilities in nonprofit and voluntary organizations: A qualitative investigation. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(4), 588–610.

Ko, W. W., & Liu, G. (2021). The transformation from traditional nonprofit organizations to social enterprises: An institutional entrepreneurship perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 171, 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04446-z

Kor, Y. Y., Mahoney, J. T., & Michael, S. C. (2007). Resources, capabilities and entrepreneurial perceptions. Journal of Management Studies, 44(7), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00727.x

Lehner, O. M., & Germak, A. J. (2014). Antecedents of social entrepreneurship: Between public service motivation and the need for achievement. International Journal of Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 3(3), 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSEI.2014.067120

Lévesque, M., & Minniti, M. (2011). Age matters: How demographics influence aggregate entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 5(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.117

Leyden, D. P. (2016). Public-sector entrepreneurship and the creation of a sustainable innovative economy. Small Business Economics, 46, 553–564.

Light, P. C. (2004). Sustaining nonprofit performance: The case for capacity building and the evidence to support it. Rowman & Littlefield.

Lind, H. B., Nordfjærn, T., Jørgensen, S. H., & Rundmo, T. (2015). The value-belief-norm theory, personal norms and sustainable travel mode choice in urban areas. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 44, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.06.001

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Sage.

Lowndes, V. (2005). Something old, something new, something borrowed… How institutions change (and stay the same) in local governance. Policy Studies, 26(3–4), 291–309.

Maguire, S., Hardy, C., & Lawrence, T. B. (2004). Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 657–679.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.002Getrightsandcontent

Marvel, M. R., Davis, J. L., & Sproul, C. R. (2016). Human capital and entrepreneurship research: A critical review and future directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(3), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12136

McDonald, R. E. (2007). An investigation of innovation in nonprofit organizations: The role of organizational mission. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(2), 256–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764006295996

Markides, C. C., & Williamson, P. J. (1996). Corporate diversification and organizational structure: A resource-based view. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 340–367. https://doi.org/10.5465/256783

Miller, T. L., Grimes, M. G., McMullen, J. S., & Vogus, T. J. (2012). Venturing for others with heart and head: How compassion encourages social entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 616–640.

Miller, M. P. (1998). Small is beautiful—but is it always viable? In M. L. Mussoline (Ed.), New directions for philanthropic fundraising (Vol. 20, pp. 93–106). Jossey-Bass.

Minniti, M., & Lévesque, M. (2010). Entrepreneurial types and economic growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(3), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.002

Morris, M. H., Santos, S. C., & Kuratko, D. F. (2021). The great divides in social entrepreneurship and where they lead us. Small Business Economics, 57, 1089–1106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00318-y

Morris, M. H., Webb, J. W., & Franklin, R. J. (2011). Understanding the manifestation of entrepreneurial orientation in the nonprofit context. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 947–971. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00453.x

Moss, T. W., Short, J. C., Payne, G. T., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2011). Dual identities in social ventures: An exploratory study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(4), 805–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00372.x

Neffke, F., & Henning, M. (2013). Skill relatedness and firm diversification. Strategic Management Journal, 34(3), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2014

Nelson, R., & Winter, S. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge. Belknap Press of Harvard University.

Nitterhouse, D. (1997). Financial management and accountability in small, religiously affiliated nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 26(4_suppl), S101–S121.

Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. E., Piliavin, J. A., & Schroeder, D. A. (2005). Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 365–392. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070141

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. John Wiley.

Peredo, A. M., & McLean, M. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: A critical review of the concept. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007

Perkmann, M. (2007). Policy entrepreneurship and multilevel governance: A comparative study of European cross-border regions. Environment and Planning c: Government and Policy, 25(6), 861–879.

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140303

Petersen, T., & Saporta, I. (2004). The opportunity structure for discrimination. American Journal of Sociology, 109(4), 852–901. https://doi.org/10.1086/378536

Pinillos, M. J., & Reyes, L. (2011). Relationship between individualist–collectivist culture and entrepreneurial activity: Evidence from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor data. Small Business Economics, 37, 23–37.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hamel, G. (1994). Strategy as a field of study: Why search for a new paradigm? Strategic Management Journal, 15(S2), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250151002

Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2007). Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation and success. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 16, 353–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.07.007

Robinson, P. B., & Sexton, E. A. (1994). The effect of education and experience on self-employment success. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)90006-X

Ruebottom, T. (2013). The microstructures of rhetorical strategy in social entrepreneurship: Building legitimacy through heroes and villains. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(1), 98–116.

Salamon, L. M., & Sokolowski, W. (2001). Volunteering in cross-national perspective: Evidence from 24 countries. Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies.

Salamon, L. M. (1992). America’s nonprofit sector: A primer. The Johns Hopkins University, The Foundation Center.

Sallis, E., & Jones, G. (2002). Knowledge Management in Education. Kogan Page.

Santos, F., Pache, A. C., & Birkholz, C. (2015). Making hybrids work: Aligning business models and organizational design for social enterprises. California Management Review, 57(3), 36–58. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2015.57.3.3

Schulz, T., & Baumgartner, D. (2013). Volunteer organizations: Odds or obstacle for small business formation in rural areas? Evidence from Swiss Municipalities. Regional Studies, 47(4), 597–612.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences and altruism. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, 10 pp. 221e279). N.Y: Academic Press.

Schwartz, S. H. (1975). The justice of need and the activation of humanitarian norms. Journal of Social Issues, 31, 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1975.tb00999.x

Schwartz, S. H., & Clausen, G. T. (1970). Responsibility, norms, and helping in an emergency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16, 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029842

Schwartz, S. H., & Howard, J. A. (1984). Internalised values as moderators of altruism. In E. Staub, D. Bar-Tal, J. Karylowski, & J. Reykowski (Eds.), Development and Maintenance of Prosocial Behavior (pp. 229–255). Plenum Press.

Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00017-2

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791611

Shaw, E., & Carter, S. (2007). Social entrepreneurship: Theoretical antecedents and empirical analysis of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 14(3), 418–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000710773529

Shepherd, D. A., Wennberg, K., Suddaby, R., & Wiklund, J. (2019). What are we explaining? A review and agenda on initiating, engaging, performing, and contextualizing entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 45(1), 159–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318799443

Shockley, G. E., Stough, R. R., Haynes, K. E., & Frank, P. M. (2006). Toward a theory of public sector entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 6(3), 205–223.

Solcová, I., & Kebza, V. (2005). Health protective factors and health protective behaviors of Czech entrepreneurs: Comparison to a population sample. Studia Psychologica, 47(1), 17.

Sørensen, J. B., & Sharkey, A. J. (2014). Entrepreneurship as a mobility process. American Sociological Review, 79(2), 328–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414521810

Stephan, U., Uhlaner, L. M., & Stride, C. (2015). Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. Journal of International Business Studies, 46, 308–331.

Stevenson, H. H., & Jarillo, J. C. (1990). A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 17–27.

Strichman, N., Bickel, W. E., & Marshood, F. (2008). Adaptive capacity in Israeli social change nonprofits. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37(2), 224–248.

Tan, W. L., Williams, J., & Tan, T. M. (2005). Defining the ‘social’in ‘social entrepreneurship’: Altruism and entrepreneurship. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1, 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-005-2600-x

Tumasjan, A., Welpe, I., & Spörrle, M. (2013). Easy now, desirable later: The moderating role of temporal distance in opportunity evaluation and exploitation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(4), 859–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00514.x

Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (2008). Opportunity identification and pursuit: Does an entrepreneur’s human capital matter? Small Business Economics, 30(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9020-3

Unger, J. M., Rauch, A., Frese, M., & Rosenbusch, N. (2011). Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.09.004

Urbano, D., Aparicio, S., & Querol, V. (2016). Social progress orientation and innovative entrepreneurship: An international analysis. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 26, 1033–1066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-016-0485-1

Van Praag, C. M. (2003). Business survival and success of young small business owners. Small Business Economics, 21(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024453200297

Venkataraman, S. (1997). The distinctive domain of entrepreneurship research. Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth, 3(1), 119–138.

Vining, J., & Ebreo, A. (1992). Predicting recycling behavior from global and specific environmental attitudes and changes in recycling opportunities. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22, 1580–1607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb01758.x

Wamuchiru, E., & Moulaert, F. (2018). Thinking through ALMOLIN: The community bio-centre approach in water and sewerage service provision in Nairobi’s informal settlements. Journal of Environmental Planning & Management, 61(12), 2166–2185.

Welter, F., Baker, T., & Wirsching, K. (2019). Three waves and counting: The rising tide of contextualization in entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0094-5

Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrepreneurship—conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00427.x

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050207

Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (1998). Novice, portfolio, and serial founders: Are they different? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(3), 173–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)90002-1

Wright, M., Robbie, K., & Ennew, C. (1997). Venture capitalists and serial entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(3), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(96)06115-0

Wood, M. S., & Pearson, J. M. (2009). Taken on faith? The impact of uncertainty, knowledge relatedness, and richness of information on entrepreneurial opportunity exploitation. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 16(2), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051809335358

Young, D. R. (1986). Entrepreneurship and the behavior of nonprofit organizations: Elements of a theory. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), The economics of nonprofit institutions: Studies in structure and policy (pp. 161–184). Oxford University Press.

Zietsma, C., & Lawrence, T. B. (2010). Institutional work in the transformation of an organizational field: The interplay of boundary work and practice work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(2), 189–221.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chowdhury, F., Audretsch, D.B. Is Nonprofit Entrepreneurship Unique?. Small Bus Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-024-00885-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-024-00885-4

Keywords

- Nonprofit entrepreneurship

- Values

- Social orientation

- Knowledge resources

- Education

- Human capital

- Industry experience

- Job roles