Abstract

For the past four decades, intercultural bilingual education (IBE) has been a common policy prescription to address Indigenous/non-Indigenous education gaps in Latin America. Initiatives have grown from small, localised pilots to national and state-level initiatives across thousands of schools. While there is some rigorous evidence of the effectiveness of IBE pilot initiatives at a small scale, there is very little evidence that expanding them to a larger scale benefits learners to the same extent. This article reviews the existing evidence on IBE’s effectiveness and identifies a number of challenges in replicating success at scale. The authors identify factors which have limited our understanding of IBE’s effectiveness, as well as factors which may have contributed to less-than-ideal outcomes for larger programmes, including uneven coverage, varying teacher quality, and limited resource availability for smaller Indigenous languages. Addressing these issues will be crucial for improving IBE programmes’ ability to operate successfully at scale.

Résumé

Des projets pilotes aux politiques : les difficultés pour mettre en œuvre une éducation bilingue interculturelle en Amérique latine – Ces quatre dernières décennies, l’éducation bilingue interculturelle (EBI) a couramment été préconisée par la politique dans le but de combler les fossés entre l’éducation autochtone et non autochtone en Amérique latine. Les projets pilotes, locaux et de petite envergure au début, sont devenus des projets nationaux, menés dans des milliers d’écoles. Quoique des recherches rigoureuses prouvent l’efficacité des projets pilotes d’éducation bilingue interculturelle à petite échelle, très peu d’éléments démontrent que leur élargissement à vaste échelle soit utile dans la même mesure pour les apprenants. Cet article passe en revue les preuves existantes de l’efficacité de l’éducation bilingue interculturelle et répertorie un certain nombre de difficultés à reproduire leur succès à vaste échelle. Les auteurs identifient non seulement des facteurs qui nous ont empêchés de comprendre toute l’étendue de l’efficacité de l’éducation bilingue interculturelle, mais aussi des facteurs susceptibles d’avoir contribué à ce que les résultats des programmes de plus grande ampleur soient loin d’être idéals. Citons notamment une couverture inégale, la qualité variable des enseignants et la disponibilité limitée des ressources pour les langues autochtones moins répandues. Il est primordial de se consacrer à ces questions pour améliorer la capacité des programmes d’éducation bilingue interculturelle à porter leurs fruits à plus vaste échelle.

Resumen

Durante las últimas cuatro décadas, la educación intercultural bilingüe (EIB) ha sido una propuesta de política pública común para abordar las brechas educativas indígenas/no indígenas en Latinoamérica. Las iniciativas han crecido desde pequeños proyectos pilotos a nivel local hasta proyectos a nivel estadual y nacional, llegando a miles de escuelas. Si bien existe evidencia rigurosa de la eficaz de las iniciativas pilotos a una escala reducida, hay poca evidencia que su expansión a una escala más grande pueda beneficiar a los estudiantes en la misma medida. En este trabajo se revisa la evidencia para la eficacia de la EIB y se identifica un conjunto de desafíos al replicar tales éxitos a gran escala. Los autores identifican los factores que han limitado nuestra comprensión de la eficacia de la EIB, así como los que han contribuido a resultados menos que ideales para programas de mayor envergadura, como la cobertura desigual, la variación en la calidad de instructores y la disponibilidad limitada de recursos para lenguas indígenas más pequeñas. Abordar estas cuestiones será central para mejorar la capacidad de los programas de EIB para funcionar con éxito a gran escala.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite recent progress towards universal enrolment of Indigenous children in primary and lower-secondary education, Indigenous children and youth in Latin America still lag behind non-Indigenous students in terms of school enrolment rates and completion, as well as performance on standardised tests. Based on data from national censuses and the World Bank from 2010 to 2020, Indigenous children aged 6–11 had lower primary school attendance rates in 11 of 17 Latin American countries, similar attendance rates in four countries (Belize, Chile, Honduras and Uruguay), and higher attendance rates in only two countries (Mexico and Nicaragua). These gaps widen for secondary schools: attendance rates were lower in 13 countries, similar in two countries (Chile and Uruguay) and higher in two countries (Belize and Nicaragua). Access to higher education is even more unequal: the gap between the percentage of Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons with some post-secondary education exceeds 100% in Bolivia, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama and Venezuela, and exceeds 50% in Belize, Costa Rica, Mexico and Nicaragua (Näslund-Hadley and Santos 2022).

Beyond school attendance, there are important gaps in educational outcomes. At the regional level, 37% of Indigenous primary school students failed to meet proficiency standards in reading and 58% in science and mathematics, compared to 17% and 42% of non-Indigenous students respectively (Näslund-Hadley and Santos 2022).Footnote 1

In Latin America, one of the most common policy responses to address these gaps has been intercultural bilingual education (IBE), and this article analyses the experience of these IBE programmes. More specifically, we seek to address the following research questions:

-

RQ1

How effective have IBE programmes been?

-

RQ2

What challenges are involved in moving from small-scale pilot interventions (where there is significant evidence of effectiveness) to national-level programmes (where there is much less evidence of effectiveness)?

-

RQ3

What are the most pressing research and policy questions for the future?

We begin with a concise literature review of studies of the effectiveness of IBE programmes in Latin America. To be included in the review, studies had to have been conducted between 1980 and 2022 and had to include a quantitative comparison of learning outcomes between students in IBE and non-IBE programmes.Footnote 2 Our review includes papers that employ quite different quantitative methodologies, but all involve one or more of the following:

-

(1)

simple comparisons of educational outcomes of students attending IBE and non-IBE schools;

-

(2)

regression analyses using individual- or household-level data on school performance and its correlates, including whether or not a student studied in an IBE school; and

-

(3)

rigorous impact evaluations of an IBE programme, which involved random assignment of schools to IBE and non-IBE curricula.Footnote 3

Our analysis is restricted to countries for which these quantitative analyses are available.

Following the literature review, we identify the following five key lessons and challenges from the implementation of IBE programmes in Latin America:

-

the limited coverage of most programmes;

-

low correlation between programme coverage and educational outcomes for Indigenous students;

-

data constraints that make it difficult to gauge the effectiveness of interventions;

-

the difficulty of developing IBE programming for languages with relatively few speakers; and

-

constraints posed by teacher quality and availability.

A final section identifies research and policy issues going forward.

Stuck in pilot mode? Analysis of IBE programme effects and impacts in Latin America

In Latin America, state-sponsored Indigenous literacy programmes have existed in Peru and Mexico since the 1930s. Virtually all initiatives in the region prior to the 1970s followed the model of transitional bilingual education, with explicit goals of religious proselytisation or cultural assimilation (López 2009). In response to Indigenous rights movements, various countries in the 1970s and 1980s moved to a “maintenance model” of bilingual education which prioritised maintaining students’ native languages (L1), rather than using L1 instruction as a temporary vehicle for the acquisition of Spanish language (L2) skills. Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Peru and Mexico were among the earliest adopters of this approach. At present, most governments in the region have implemented an IBE focus which goes beyond language maintenance to language improvement (Abram 2004).

The deliberate intercultural approach of IBE distinguishes it from other forms of bilingual education (Abram 2004). IBE pedagogy aims to improve instruction by increasing teachers’ understanding of Indigenous culture, by explicitly including Indigenous history and culture in curricula, and by emphasising the importance of students’ lived experiences in the classroom. In the 1990s, the same five nations that pioneered the maintenance model (Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico and Peru) were also those in which explicitly intercultural pedagogies became a central part of the educational system and where significant effort was devoted to IBE teaching methodologies, teacher training and curricular design (Abram 2004).

IBE is a unique and fundamentally Latin American policy solution, and any assessment of its effectiveness should rest on rigorous evaluations from the region. Lessons learned from bilingual education programmes in other regions of the world may be of limited value.Footnote 4

Three approaches have been used to gauge the effects of IBE programmes on students’ educational outcomes in Latin America. In order of increasing rigour, they are:

-

(1)

simple comparisons of outcomes of students attending IBE schools with those attending non-IBE schools, which, while illustrative, cannot identify the true impact of IBE;

-

(2)

regression analysis using household or student data sets with (usually quite basic) information on student achievement and participation in IBE, in which researchers attempt to control for potentially confounding factors other than IBE programming that affect student achievement in order to identify the effect of IBE; and

-

(3)

purpose-designed impact evaluations of IBE programmes which involve random assignment of schools to IBE and non-IBE curricula, which allow a rigorous, causal attribution of impacts to the IBE intervention.Footnote 5

The earliest statistical analyses of bilingual education programmes in Latin America use the non-universal coverage of pilot programmes to compare students’ educational outcomes in bilingual and non-bilingual schools. Since coverage of bilingual programmes is not universal, researchers can compare outcomes of interest between participating and non-participating schools. If the criteria used to decide which schools participate in the programme are not related to these outcomes – a very strong assumption – this comparison can provide an approximation of probable project impact.Footnote 6

The earliest study of this type was conducted by Nancy Modiano and Roberto Gómez Ciriza (1974), who found that second grade Indigenous children in a bilingual programme in Chiapas, Mexico, obtained higher proficiency in Spanish than their peers in Spanish-only schools.Footnote 7 A little over a decade later, Luis Enrique López (1987) found similar results for the Experimental Project of Bilingual Education (Proyecto Experimental de Educación Bilingüe) in Peru’s Puno department. In this case, positive impacts of bilingual education extended beyond Spanish language competency to both Aymara and Quechua competency and even to mathematical skills (López 1987).Footnote 8 In the 1990s, small-scale programmes in southern Mexico spurred by the Zapatista movementFootnote 9 also showed promising results in a series of natural experiments (López and Sichra 2008).

The first quantitative review of educational outcomes produced by a scaled IBE programme is Kjell Enge and Ray Chesterfield’s 1996 study of Guatemala’s national IBE programme during the late 1980s, in the period after it was expanded from a smaller pilot funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). They document higher performance scores for Indigenous students in IBE schools than for Indigenous students in non-IBE schools: on 10 of 11 state exams administered between 1988 and 1991, students in IBE schools achieved higher scores in every subject, with a particular advantage in languages. While the magnitude of these improvements varied, the average scores of Indigenous students in IBE schools were anywhere from 5% to 50% higher than those in non-IBE schools, with statistical significance at the 0.05% level (Enge and Chesterfield 1996). It is important to note that these analyses – whether using subnational or national data – only compare average test results at the school level and do not make efforts to control for other relevant variables such as school quality or student characteristics.

A second type of analysis uses household or individual-level microdata to examine the effect of access to IBE on individual student outcomes, controlling for other relevant factors. Two studies on Mexico took this approach. Susan Parker et al. (2002) used data from the Mexican Education, Health and Nutrition Programme (PROGRama de Educación, Salud y Alimentación [PROGRESA]) for more than 26,000 rural communities to look at determinants of school enrolment and years of completed education for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. They found that the presence of an IBE school in a community reduced the enrolment gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children by more than 50%.

Lucrecia Santibañez (2016) looked at determinants of standardised test scores for grade 4 students in Chiapas, using data for 2009–2010.Footnote 10 In the simplest model – which includes only variables that capture whether a student is Indigenous and whether the school attended is an IBE school – studying in IBE schools is associated with statistically significant lower scores on standardised maths and Spanish tests. When additional student and school characteristics are added to the analysis, however, the statistical significance of attending an IBE school disappears. Far from being an endorsement of IBE, Santibañez’s results therefore suggest that IBE in Mexico may at best do no harm in terms of learning outcomes.

For Guatemala, William Vasquez (2012) used 2004 data from the Ministry of Education’s performance evaluation programme (PRONERE) to identify the determinants of student performance in language and mathematics for first- and third-graders. Among the explanatory variables included are attending a bilingual school (only available in rural areas), whether schools are community-managed, whether teachers are responsible for multiple grades, and a number of other variables which control for student, teacher and school characteristics. Vasquez finds that, while IBE education does not affect student performance for first-graders (regression coefficients for IBE are positive but not statistically significant for both reading and maths skills), third-graders who attend IBE schools score significantly lower in reading (but not in maths).Footnote 11

Finally, a more recent study conducted by Disa Hynsjö and Amy Damon (2016) in Peru examined the effects of IBE on Indigenous students’ performance on standardised mathematics and Spanish-language tests for 9 of Peru’s 24 regions. In an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with controls for child, household, school and teacher characteristics, Quechua IBE students’ scores were 0.43 standard deviations higher than scores of non-IBE Quechua students on mathematics proficiency tests, with the coefficient statistically significant at the 1% level (ibid.). No statistically significant effect of IBE on language scores was detected.

While the results generated by these two types of analysis (simple comparisons and analyses using microdata) are generally promising, IBE programmes have by and large not been subject to rigorous impact evaluations. Only recently has a purpose-designed impact evaluation of an IBE programme been implemented, using a randomised controlled trial (RCT) methodology that allows causal programme impacts to be identified. The bilingual and intercultural preschool programme Ari Taen JADENKÄ (Let’s Count and Play, in Ngäbere) was launched in 2018 to address gaps in mathematical competency between Indigenous Ngäbe children and non-Indigenous children in Panama, a country which is one of the poorest performers on international standardised learning tests. JADENKÄ is heavily intercultural since it teaches both Western and Ngäbe mathematical concepts and skills.

The RCT evaluation showed that JADENKÄ increased mathematical competency by between 0.12 and 0.18 standard deviations (depending on the cohort analysed), while competency in ethnomathematics (i.e. the ability to conduct mathematical calculations using Ngäbe concepts) increased even further, by between 0.22 and 0.23 standard deviations. The authors conclude that a well-designed intercultural mathematics programme can significantly reduce gaps in maths skills between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students without forcing students to choose between academic achievement and their culture, identity and language (Näslund-Hadley et al. 2022). In sum, this specific RCT demonstrates proof-of-concept for IBE on a granular level in Panama, but strong, broad-consensus evidence for the effectiveness of IBE at scale remains to be established.

Key lessons and policy challenges

The empirical analyses summarised above illustrate the potential of IBE to improve learning outcomes for the Indigenous peoples of Latin America. In broad terms, at least two important challenges remain for researchers: increasing the rigour of analyses which examine the effectiveness of IBE programmes and, as part of these analyses, understanding factors which constrain the positive impacts of IBE programmes implemented at scale. The following discussion attempts to distil the breadth of issues facing IBE policies into five core points (Lessons #1–5) that should orient further research and policy action.

Lesson #1: IBE coverage remains limited in all countries of the region

By the early 2000s, IBE came to constitute almost all state-sponsored bilingual education policies and continues to make up the overwhelming majority of new programme rollouts in Latin America. More than half of all Latin American nations have formally pursued IBE programmes, but the scale of these programmes is limited, even in nations with significant Indigenous populations (see Table 1). In Peru, 38% of primary-school-aged Indigenous children have access to IBE, while in Chile 30% of such children have access. Mexico’s and Ecuador’s IBE programmes, on the upper end of the scale, enrol roughly 50% of Indigenous students (Näslund-Hadley and Santos 2022). Similar recent data are not available for Bolivia and Guatemala, the other two regional countries with large Indigenous populations; earlier estimates from the 2000s were 17% for Bolivia and between 30% and 50% for Guatemala (López 2009).

Higher access rates are associated with stable, longstanding government IBE programmes, with little administrative restructuring or political interference. Both Mexico and Ecuador possess established bureaucratic infrastructure for their IBE programmes, with agencies which have retained significant political stability for several decades, as well as cross-cutting government units responsible for working directly with Indigenous communities (López 2014; Oviedo and Wildemeersch 2008). Even so, in both cases, underfunding may be an issue. Mexico’s IBE directorate oversees approximately 10% of the nation’s schools (Näslund-Hadley and Santos 2022), but received only 3.1% of the national education budget in fiscal year (FY) 2021 (SG and SSPM México 2020). In Ecuador, the nation’s IBE agency oversees 11.3% of primary schools (Näslund-Hadley and Santos 2022), yet received only 0.01% of the FY 2020 education budget (MinEcoFin Ecuador 2019).

Of the nations with longstanding IBE programmes, lower access rates generally indicate an unfocused and discontinuous policy approach. In Peru, the earliest years of IBE policy saw an overreliance on foreign investment and frequent restructuring of the agency responsible for IBE within the education ministry. In Guatemala, limited coverage has been a function of significant reliance on external funding sources.

Given the limited coverage rates of IBE schools, the competence in Indigenous languages of teachers in non-IBE schools is an important issue. The academic performance of Indigenous students in non-IBE schools may be largely dependent on teacher quality. Aside from Paraguay (which has a majority of bilingual speakers), teacher shortages in Latin America mean that multilingual teachers who are able to communicate in an Indigenous language are unable to fully staff even IBE schools (see Lesson #5 for further detail). When Indigenous languages do appear in traditional schools, this is often in the form of smaller “enrichment programmes” which offer little beyond infrequent, disconnected vocabulary and grammar lessons (Kvietok Dueñas 2020).Footnote 12

Bridging the gap to full coverage of IBE means learning from the patterns observed in localities with better access rates. How might programmes be designed to ensure long-term stability? Promoting the political autonomy of IBE directorates is a key first step, which involves actors at multiple levels within the political system. At the constitutional level, countries like Mexico and Ecuador explicitly recognise themselves as multinational, according Indigenous populations a legally enforceable right to education, language and culture. In particular, Ecuador’s model emphasises the importance of strong community-level involvement by Indigenous communities.Footnote 13 Ecuador’s IBE curricula are designed by the nation’s formal Indigenous confederation itself. Such a model is obviously not automatically transferrable to other Latin American nations, but including units of Indigenous governance (such as the municipal usos y costumbres [customs and traditions] system in Mexico or the Indigenous comarcas [autonomous districts] in Panama)Footnote 14 in the management of IBE programmes may be a feasible goal. Further insulation from political volatility may be achieved through multi-year budgeting for IBE directorates or by involving international development banks in programme expansion.

Lesson #2: Broader IBE coverage does not ensure better educational outcomes

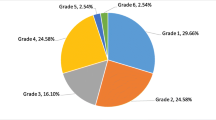

Although evidence on the effectiveness of IBE programmes in the region is scarce and preliminary, there does not seem to be a correlation between coverage rates and educational outcomes. In the 2019 Regional Comparative and Explicative Study (Estudio Regional Comparativo y Explicativo [ERCE]; UNESCO 2021),Footnote 15 Mexico and Ecuador – the countries with by far the highest level of IBE coverage in the region – had similar Indigenous/non-Indigenous testing gaps to Peru and Guatemala, countries with much lower IBE coverage (see Table 1). In fact, the research cited in the previous section shows no effect of IBE on Indigenous students’ performance in Mexico, while there is limited evidence that the Guatemalan programme and the smaller-scale initiatives in Peru may be associated with better educational performance. Furthermore, overall secondary school enrolment rates for Indigenous students are comparable between the two higher-access nations (Mexico and Ecuador) and middle-access nations such as Peru; rates of attendance in primary schools have remained in the mid-90% range for Mexico, Ecuador and Peru over the past decade (World Bank 2015; Näslund-Hadley and Santos 2022).

The lack of correlation between IBE coverage and educational outcomes may be explained in part by difficulties in accurately measuring coverage. In Mexico, Ecuador, Peru and Chile, access rates are defined by the number of IBE schools participating in the bilingual education programmes run by state (Mexico) or national education ministries. The accreditation of these schools as “IBE classrooms” does not involve regular monitoring or require continual certification by IBE directorates. Reported data on the number of IBE schools may be inflated, including schools which do not implement curricula properly, use an Indigenous language, or employ high-quality teachers. In countries like Guatemala or Bolivia, where state accreditation of IBE schools is absent altogether, estimated access rates are even less useful as a measure of coverage.

Lesson #3: Lack of data makes it difficult to gauge the effectiveness of IBE programming. Generating better data should therefore be a high policy priority

Many of the data sources upon which the analyses reviewed in this article are based leave significant gaps. Government-generated data may be able to provide test scores in some cases (using either standardised international instruments or national measures), but these sources rarely have information on student- or school-level determinants of educational outcomes, both of which are necessary to control for potentially important determinants of student performance. More critically, in many nations, basic data comparing IBE and non-IBE schools are absent altogether.

The more recent analyses reviewed in this article have had to rely on unique and fortuitous circumstances to collect data at the household- and school-level. Hynsjö and Damon’s analysis of IBE in Peru relies on an international Oxford University survey which included what the authors dub “unusually detailed data” regarding Indigenous schooling. Santibañez relies on a detailed 2010 survey commissioned by a Mexican think tank on IBE programmes in Chiapas. Surveys with this level of detail are uncommon and do not provide a comprehensive look at the region as a whole. It is no accident that analytical work on the effectiveness of IBE has been overwhelmingly focused on Mexico, Guatemala and Peru, where at least some data on ethnicity, educational outcomes and their determinants are available.

A more general understanding of IBE’s success at scale, however, will require research on other national systems such as those of Chile or Ecuador, where there are currently no data sets that permit these types of analysis. Extending existing international educational surveys which already include both test scores and school-specific information, such as ERCE, to include more information regarding school policy may be a useful way to expand data collection.Footnote 16

Lesson #4: Widely spoken Indigenous languages are the logical target for IBE programmes. It is difficult to design and implement IBE for smaller, more localised languages

Another consideration is the need to better understand the impacts of IBE programmes on smaller Indigenous languages. Intuitively, providing the curricular and administrative infrastructure to support a wide variety of languages is much more difficult than doing so for only two or three languages.Footnote 17

Anecdotal evidence shows that there are barriers to adapting programmatic IBE to smaller languages. Disaggregation of student benchmark results in Peru illustrate that IBE initiatives which target languages outside of the widely-spoken Quechua and Aymara dialects, even those which benefit from targeted government support, show much lower rates of satisfactory performance (MinEdu Perú 2016). For less-spoken languages, core issues include adapting vocabulary to tackle the more complex academic or scientific concepts found in the classroom (O’Grady and Hattori 2016), and standardising grammar for languages which often lack central grammar academies, broadly accepted writing conventions or a broad corpus of written texts (Dalton et al. 2019). Finding sufficiently qualified speakers to design culturally and linguistically informed curricula, textbooks and classroom materials is a major concern for IBE in general, and the severity of these concerns is only amplified for smaller languages. Guatemala and Ecuador have both made efforts to address these issues, pioneering a community-based approach to curriculum design and the creation of classroom materials (Oviedo and Wildemeersch 2008; Dalton, et al. 2019).

While many nations’ IBE programmes invest substantially in less common languages, so far, no major analysis has explicitly reviewed the effectiveness of state-run programmes for smaller languages. It may be productive to evaluate whether governments’ choices to prioritise certain languages over others translates to impacts in the classroom for languages which receive stronger government support. At present, we have no concrete data to show whether the issues faced by smaller languages in national IBE programmes emerge as a result of ineffective instruction or the inefficiency inherent in running many highly diversified programmes (or a combination of these factors).

Future evaluations may be better informed by segregating Indigenous students’ performance data based on native language. Evaluating IBE at the language level (rather than national, community, school, etc.) could contribute to our understanding of large-scale implementation. This would allow for individual rather than aggregated review of the effectiveness of the curricula, classroom materials, or other resources created for each particular language programme.Footnote 18 In Mexico specifically, where investment varies according to language and where 36 recognised Indigenous languages still lack government-published teaching materials (Santibañez 2016), language-level analysis would be particularly useful in measuring the success of top-down government approaches in reaching smaller linguistic minorities.

Lesson #5: Teacher quality and availability limit the effectiveness of IBE, but solutions are not simple

The lack of an adequate IBE teaching corps presents a significant problem. There are two important components here: teacher quality and teacher availability.

The weaknesses in teacher quality are well documented by observational research. Jeffery Marshall (2009) notes that teacher knowledge, evaluated through qualitative surveys or in-person observation, is generally a strong predictor of student outcomes in Latin America. Across the region, IBE programmes have not scored well in this regard. Observational descriptions of IBE teaching practices emphasise heterogeneity at the classroom level (De Mejía 2004; Grino 2019): teachers do not always abide by the same standards for engagement with students or with course materials. Reliance on rote memorisation and lack of commitment to ongoing L1 instruction are relatively common (López 2009). Teachers in Mexico’s IBE schools typically score lower in student evaluations and have less technical training and occupational experience than those in non-Indigenous schools (Santibañez 2016). Eleonora Bertoni et al. (2021) note that temporary contracts and a lack of formal certification are common for teachers in Indigenous schools.

There is strong reason to believe that poorer teacher quality may impact test scores. It is telling that, of the studies discussed in this article, some of the most positive results come from the Guatemalan experience in the mid-1980s, when significant resources were devoted to ensuring quality teaching staff (Enge and Chesterfield 1996). When the nation’s programme was expanded in the mid-1980s, more than 75% of teachers in Guatemala’s IBE schools had been directly trained in bilingual pedagogy and more than 81% spoke the Mayan language they were teaching.

Beyond quality, simple availability of IBE teachers often constrains implementation. In explaining the poor results of IBE in Chiapas, Santibañez contends that the Indigenous teaching pool in the state is too small for schools to be discerning in hiring practices. Fewer than 15% of teaching candidates in Mexico passed the national entrance exam which would qualify them to be hired in IBE primary school programmes (Santibañez 2016). As a result, IBE schools are forced to hire teachers who may not even be proficient in Indigenous languages – some 40% of all IBE teachers in Mexico – thus undermining a critical plank of IBE intervention. In short, there may simply not be enough teachers to staff IBE programmes.

Retaining the teachers who are hired is a further concern. The concentration of Indigenous schools in rural regions with fewer housing prospects or opportunities for supplemental income may make it more difficult to retain staff. Chiapas’ Indigenous schools saw an annual teacher attrition rate of 30% from 2009 to 2011 (Santibañez 2016). Such high turnover makes it difficult for IBE teachers to gain experience. We know little about the factors behind these supply issues. The drivers of limited teacher availability – which may serve as policy levers – are not well understood.

A number of proposed policy solutions exist for this issue. Offering pay supplements to certified Indigenous language teachers has been explored in both Mexico and Guatemala as a way to improve teacher quality (López 2014). However, such certifications focus primarily on written and spoken fluency in the language, and not on the ability to teach it effectively – a factor which has been anecdotally cited as contributing to poorer classroom outcomes in both nations.Footnote 19 Some researchers argue for the potential of training and certification programmes to improve educators’ skill sets (Bertoni et al. 2018), while others are concerned that requiring additional qualifications may dissuade potential teachers from entering a profession which already suffers from a teacher shortage (Santibañez 2016). Significant qualitative work is needed on this topic, beginning with interviews of teachers both entering and exiting IBE programmes to provide additional information on how and why teachers join and leave IBE programmes.

When it comes to attracting new teachers, Indigenous communities themselves may provide interesting solutions. While most state-trained teachers are taught monolingual teaching methods, in both Guatemala and Ecuador Indigenous-led IBE programmes aim to involve community members as educators, at times circumventing state-run teacher training schemes altogether (Oviedo and Wildemeersch 2008; López 2009). An analysis comparing student outcomes and longevity of employment between state-trained and Indigenous-trained teachers may provide a promising avenue of research. Furthermore, surveys investigating the professional motivations of teachers-in-training, an understudied area of qualitative research, could establish guidelines for nudging more linguistically and culturally qualified Indigenous Latin Americans towards the teaching profession.

Finally, technology may play some role in improving teacher quality. Given the lack of connectivity in the vast majority of rural schools where IBE programmes are implemented, it is difficult to imagine the widespread adoption of synchronous distance learning in which a highly qualified and skilled teacher provides instruction to students in a remote location via internet connection, supported by a local teacher in the remote location. However, non-synchronous, technology-enhanced instruction may be both effective and relatively low-cost.

Conclusions

While our literature review and lessons learned reflect the existing knowledge base, the conclusions we offer here are far from definitive; there is a clear mandate for further research and experimentation. What is clear is that IBE is not a panacea that will magically close the gaps in educational outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. Other, complementary actions are needed, including investment in the same evidence-based pedagogical methodologies that are used to promote better outcomes for non-Indigenous students. Even so, results from small-scale IBE initiatives like JADENKÄ are quite promising; the question is how to get these programmes to scale.

Widening our understanding of IBE’s effectiveness and potential for scalability will require researching its heterogeneity in implementation using both qualitative and quantitative methods. The varying linguistic settings between and within countries necessitates focused attention. Building on the limited policy-focused studies available which analyse subnational rollouts, as well as ensuring that future educational surveys in the region capture data on factors which may impede success at the subnational and national levels, will be critical in improving the state of the IBE in the region.

While the problems faced by Latin America’s IBE programmes are complex, the core lessons of this article suggest several potential policy changes may be helpful, including: (1) vertical linkages between IBE directorates, bodies of Indigenous governance, and long-term budgets; (2) improved accreditation for IBE schools and metrics for implementation at the classroom level; (3) improved measurement tools to capture Indigenous student performance, classroom environment and language use; (4) community-led development of curricula, textbooks and other materials; and (5) further qualitative analysis of IBE teacher motivations and exploration of experimental teaching models, including Indigenous-trained teachers and asynchronous instruction.

Although it is not entirely clear why large-scale programmes have not seen the same success as pilot programmes, encouraging policymakers to consider questions of equitable coverage, teacher quality and linguistic diversity will be strong first steps in improving outcomes. While econometric analyses have shown promising results for small-scale IBE programmes, the challenges in generating these results at scale provide a clear justification for reflection and reform.

Notes

Table 1 (featured below in the section entitled “Key lessons and policy challenges”) details Indigenous/non-Indigenous performance gaps on the 2019 Regional Comparative and Explicative Study (Estudio Regional Comparativo y Explicativo [ERCE]; UNESCO 2021) for the Latin American countries with the largest share of Indigenous population (as a percentage of total population), as well as for other countries whose bilingual education programmes we review in this article.

Purely qualitative studies were not included in our review. Relevant studies were identified via a thorough review of all search results containing the phrase “intercultural bilingual education” and “outcome” on Google Scholar, reviews of all publications in the journals Economics of Education Review, International Journal of Educational Development and International Review of Education, and all cited works in major World Bank and UNESCO reports on Indigenous education from 2010 to 2021.

These three methodological approaches are discussed in more detail in the following section.

Programmes in North America and Oceania tend to prioritise transitional approaches. Across much of Asia and Africa, mother-tongue education (MTE) has emerged as a de jure form of additive language education. Although nations like India are able to produce students with bi- or trilingual outcomes, such programmes often lack a robust intercultural element. With the exception of South Africa, many also lack the social dimension of IBE, which is geared towards recognising and fostering Indigenous citizenship. Similar to the spirit of IBE, post-apartheid South African language policy establishes the right of every student to be educated in their home language. However, unlike Latin American IBE, MTE in South Africa is not pursued through a centralised state programme. State intervention is only required when “mother tongue education is reasonably practicable” (van der Walt and Ruiters 2011, p. 86). With poor provision of in-language resources or qualified teachers, the norm for bilingual South African schools is a transition to English by grade 3 (García et al. 2017).

It is crucial to note that many of the programmes discussed below likely include classrooms which are ostensibly labelled as providing intercultural and bilingual education, but, for a host of reasons, may not actually do so. The difficulty in identifying the appropriate implementation of IBE at the classroom level is discussed in more detail in in the subsection on Lesson #2 below.

It is difficult to imagine that selection criteria are not linked to programme outcomes. For a discussion of these criteria and their potential impact on outcomes, see Cueto and Secada (2003).

For this and all other papers reviewed in this article, the debate about how to avoid bias in measuring educational outcomes for Indigenous students – and the specific concern that standardised tests are often discriminatory (see for example Preston and Claypool 2021) – is extremely relevant. Despite their shortcomings, standardised tests are widely used to evaluate student and school system performance.

These early programmes were bilingual but not explicitly intercultural.

The Zapatista movement was an Indigenous uprising that began in Chiapas, Mexico, in 1994. According to Iker Reyes Godelmann, it was “an eye-opening event for both the Mexican government and the non-indigenous population to realise the alarming situation of indigenous people in Chiapas. The indigenous conflict in Chiapas not only provoked a domestic awareness of indigenous rights, recognition and self-determination, but also an international awakening on these issues” (Godelmann 2014, online).

Data were collected from a random sample of traditional, Indigenous and community schools. At the selected schools, surveys were administered to all grade 4 students during the 2009/2010 school year.

While Vasquez’s regressions include a dummy for ethnicity, this dummy variable is not compared with attendance at an IBE school. Thus, we are unable to know whether IBE schools have differential impacts on Indigenous and non-Indigenous students (and it is quite plausible that IBE will improve educational outcomes much more for Indigenous students).

Dayana and Alexandria Sala (K’iche’-descendant high school and college students), in discussion with the first author of this article, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, June 2022.

These factors are obviously related to the political situations faced by Indigenous peoples in the countries mentioned. However, Indigenous politics are by no means the only factor influencing the structure of IBE programmes. For more detail, see López (2014).

The Mexican municipal usos y costumbres system applies and recognises Indigenous customary law. In Panama, the system of Indigenous comarcas fulfils the same function.

“For the 2019 implementation period of the Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (ERCE as per the acronym in Spanish), the Latin American Laboratory for Assessment of the Quality of Education (LLECE), part of the Regional Bureau for Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (OREALC/UNESCO Santiago), included the following countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Dominican Republic, and Uruguay” (UNESCO 2021, p. 5).

The ERCE 2019 datasets – available for 16 Latin American and 2 Caribbean countries (see footnote 15) – frequently include reasonable data on household characteristics that influence school attendance and performance, as well as on the ethnicity of students in countries with sizeable Indigenous populations. However, the school-level variables in ERCE 2019 did not collect data on factors which reflect the ability to deliver an IBE curriculum. For details, see the executive summary for the ERCE surveys (UNESCO 2021), as well as the specific national reports available at https://es.unesco.org/news/resultados-logros-aprendizaje-y-factores-asociados-del-estudio-regional-comparativo-y [accessed 27 November 2023].

The choice not to support IBE for languages not spoken by a large number of people may hasten the demise of languages already at risk of extinction.

At the same time, the limited sample size available for some minority languages – many of which register only several thousand speakers – may complicate robust data analysis.

Telma Can Pixabaj (professor of linguistics, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [UNAM], San Cristóbal de Las Casas), in discussion with the first author of this article, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, June 2022.

References

Abram, M.. (2004). Estado del arte de la educación bilingüe intercultural en América Latina [State of the art of intercultural bilingual education in Latin America]. Washington, DC: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo [Inter-American Development Bank]. Retrieved 27 November 2023 from https://www.humanas.unal.edu.co/colantropos/files/2714/7941/3665/Estado_del_arte_de_la_educacion_bilingue_intercultural_en_America_Latina__.pdf

Bertoni, E., Elacqua, G., Jaimovich, A., Rodriguez, J., & Santos, H. (2018). Teacher policies, incentives, and labor markets in Chile, Colombia, and Perú: Implications for equality. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.18235/0001319

Bertoni, E., Elacqua, G., Marotta, L., Martínez, M., Vargas, C., Montalva, V., Santos, H., & Olson, A. (2021). Escasez de docentes en Latinoamérica: ¿Cómo se puede medir y qué políticas están implementando los países para resolverlo? [Teacher shortages in Latin America: How can they be measured and what policies are countries implementing to address them?]. IDB Technical Note. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Cueto, S., & Walter Secada, W. (2003). Eficacia escolar en escuelas bilingües en Puno, Perú. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 1(1), Art. no. 4. https://doi.org/10.15366/reice2003.1.1.004

Dalton, K., Hinshaw, S., & Knipe, J. (2019). Guatemalan Ixil community teacher perspectives of language revitalization and mother tongue-based intercultural bilingual education. FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education, 5(3), 84–104. https://doi.org/10.32865/fire201953144

De Mejía, A.-M. (2004). Bilingual education in Colombia: Towards an integrated perspective. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7(5), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050408667821

Enge, K. I., & Chesterfield, R. (1996). Bilingual education and student performance in Guatemala. International Journal of Educational Development, 16(3), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-0593(95)00038-0

García, O., Lin, A., & May, S. (Eds) (2017). Bilingual and multilingual education (3rd edn). Encyclopedia of Language and Education series. Cham: Springer. Retrieved 27 November 2023 from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02258-1.pdf

Godelmann, I. R. (2014). The Zapatista movement: The fight for indigenous rights in Mexico. Australian Institute of International Affairs, 30 July [web news]. Retrieved 8 January 2024 from https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/news-item/the-zapatista-movement-the-fight-for-indigenous-rights-in-mexico/

Grino, P. (2019). Science teaching and indigenous education in Latin America: Documenting indigenous teachers teaching science in Southern Mexico. Master’s dissertation, University of Arizona. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/636524

Hynsjö, D., & Damon, A. (2016). Bilingual education in Peru: Evidence on how Quechua-medium education affects indigenous children’s academic achievement. Economics of Education Review, 53, 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.05.006

Kvietok Dueñas, F. (2020). Crafting Quechua language education in an urban high school. ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America, 19(2), Art. no. 17. Retrieved 27 November 2023 from https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/crafting-quechua-language-education-in-an-urban-high-school/

Latinobarómetro (2018). Latinobarómetro 2018: banco de datos [Latinobarómetro 2018: database] [online]. Retrieved 9 September 2022 from https://www.latinobarometro.org/latContents.jsp

López, L. E. (1987). Balance y perspectivas de la educación bilingüe en Puno [Balance and prospects for bilingual education in Puno]. Allpanchis, 19(29/30), 347–381. https://doi.org/10.36901/allpanchis.v19i29/30.980

López, L. E. (2009). Reaching the unreached: Indigenous intercultural bilingual education in Latin America. Background paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2010. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 27 November 2023 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000186620

López, L. E. (2014). Indigenous intercultural bilingual education policy in Latin America: Widening gaps between policy and practice. In R. Cortina (Ed.), The education of Indigenous citizens of Latin America (pp. 19–49). Bristol: Channel View Publications Ltd/Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783090969-004

López, L. E., & Sichra, I. (2008). Intercultural bilingual education among indigenous peoples in Latin America. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Language and Education, (pp. 1732–1746). Boston, MA: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30424-3_132

Marshall, J. H. (2009). School quality and learning gains in rural Guatemala. Economics of Education Review, 28(2), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.10.009

MinEdu Perú (Ministerio de Educación de Perú) (2016). Plan nacional de educación intercultural bilingüe al 2021 [National intercultural bilingual education plan for 2021]. Lima: Ministerio de Educación. https://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12799/5105

MinEcoFin Ecuador (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas de Ecuador) (2019). Proforma del presupuesto general del estado consolidado por entidad egresos [Proforma of the general budget of the consolidated state by entity expenditures]. Quito: Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas. Retrieved 27 November 2023 from https://www.finanzas.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/13-Por_Entidad_Egresos.pdf

Modiano, N., & Ciriza, R. G. (1974). La educación indígena en los Altos de Chiapas [Indigenous education in the highlands of Chiapas]. Antropología social series: Colección Sepini. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional Indigenista.

Näslund-Hadley, E., Hernandez-Agramonte, J. M., Santos, H., Albertos, C., Grigera, A., Hobbs, C., & Álvarez, H. (2022). The effects of ethnomathematics education on student outcomes: The JADENKÄ Program in the Ngäbe-Buglé Comarca, Panama. IDB Working Paper no. IDB-WP-01290. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.18235/0004150

Näslund-Hadley, E., & Santos, H. (2022). Skills development of indigenous children, youth, and adults in Latin America and the Caribbean. IDB Technical Note no. IDB-TN-02410. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.18235/0003954

O’Grady, W., & Hattori, R. (2016). Language acquisition and language revitalization. Language Documentation & Conservation, 10, 46–58. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24686

Oviedo, A., & Wildemeersch, D. (2008). Intercultural education and curricular diversification: The case of the Ecuadorian intercultural bilingual education model (MOSEIB). Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 38(4), 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920701860137

Parker, S., Rubalcava, L N., & Teruel, G. (2002). Schooling inequality among the indigenous: A problem of resources or language barriers? SSRN Scholarly Paper 1814698. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1814698

Preston, J. P., & Claypool, T. R. (2021). Analyzing assessment practices for Indigenous students. Frontiers in Education, 6, Art. no. 679972. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.679972

Santibañez, L. (2016). The indigenous achievement gap in Mexico: The role of teacher policy under intercultural bilingual education. International Journal of Educational Development, 47, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.015

SG & SSPM México (Secretaría General and Secretaría de Servicios Parlamentarios de México) (2020). Proyecto de presupuesto público federal para la función educación, 2020–2021 [Proposed federal public budget for the education function, 2020-2021]. Mexico City: Cámara de Diputados de la LXIV Legislatura. Retrieved 27 November 2023 from https://www.diputados.gob.mx/sedia/sia/se/SAE-ASS-22-20.pdf

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) (2021). Los aprendizajes fundamentales en América Latina y el Caribe, Evaluación de los logros de los estudiantes: Estudio Regional Comparativo y Explicativo (ERCE 2019); Resumen [Fundamental learnings in Latin America and the Caribbean, Student learning achievement assessment: Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (ERCE 2019); executive summary]. Paris: UNESCO. English version retrieved 27 November 2023 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380257_eng

van der Walt, C., & Ruiters, J. (2011). Every teacher a language teacher? Developing awareness of multingualism in teacher education. Journal for Language Teaching, 45(2), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.4314/jlt.v45i2.5

Vasquez, W. F. (2012). Supply-side interventions and student learning in Guatemala. International Review of Education, 58(1), 9–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-012-9263-y

World Bank (2015). Indigenous Latin America in the twenty-first century: The first decade. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/145891467991974540/pdf

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Emma Näslund-Hadley and two anonymous referees for their comments. The authors also extend their thanks to the instructors and staff of Tulane University’s Mayan Language Institute, the Sala family of Quetzaltenango, Guatemala and the Tahay Tzaj family of Nahualá, Guatemala for their kindness, excellent tutelage and passion for cross-cultural exchange.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no that they have no financial interests relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Porter, J.M., Morrison, A.R. From pilots to policies: Challenges for implementing intercultural bilingual education in Latin America. Int Rev Educ 70, 11–28 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-023-10039-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-023-10039-5