Abstract

Cross-owners, investors who have stakes in both the acquiring and target firms, are likely to focus on the total portfolio wealth effects from mergers and acquisition transactions, rather than the wealth effects of the target or bidder. Cross-owners may be less concerned with value destroying deals because their lack of gains, or even losses, as ownership in the acquiring firm can be offset by benefits derived from their ownership in the target firm. In contrast, shareholders with no cross-ownership, but own shares in either the target or the acquiring firm only, consider the value prospects for the target, thus producing heterogeneous incentives among shareholders to accept an offer. We investigate this heterogeneity within targets of 481 US negative premium deals and find substantial heterogeneity in acquisition incentives within the target firm shareholder base. Target shareholders in negative premium acquisitions experience negative wealth effects, but institutional cross-owners of negative acquisition premium deals realize positive wealth effects. We also find strong evidence of a size effect, where the observed wealth effects are amplified in larger deals. The divergent interests within the target shareholder base, with the attendant heterogeneous incentives to support deals, limits the monitoring capacity of institutional owners in negative premium deals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Conversely, greater ownership concentration may reduce firm value by over-monitoring, as it could discourage managers from making costly firm-specific investments, thereby missing out of profitable investment opportunities (Aghion and Tirole 1997).

Other effects that stem from cross-ownership have also been identified within the context of intra-industry competition. He and Huang (2017) investigate the effects of institutional cross-ownership of same-industry firms on product market performance and behavior. They find that cross-ownership by large institutional owners is beneficial for the cross-owned firm through product market collaboration (e.g., joint ventures) and improved innovation and operating profitability. Azar et al. (2018), however, report evidence of anticompetitive effects of cross-ownership within the airline industry.

Harford et al. (2011) conduct a shareholder-level analysis of cross-ownership and report evidence that the size of cross-holdings is too small to influence acquisition incentives. They find that bidders do not bid more aggressively, even when cross-ownership stakes are large, and they contend that cross-ownership does not explain value-reducing acquisitions. Furthermore, using a sample of takeovers in the United Kingdom, Becht et al. (2016) find that cross-holdings are too small to affect voting outcomes.

The M&A literature, including Schwert (1996), has shown that anticipation of an acquisition attracts informed trading, which can cause a high run-up in the target stock price prior to an announcement. The price of the target firm 4 weeks prior to the acquisition announcement serves as a good cutoff point to avoid including the price-run up in the calculation of the acquisition premium.

In addition to the premium calculated based on the target market value four weeks prior to the announcement, premium based on target valuations one week and one day prior to the announcement were also constructed. The differences among these samples is negligible; therefore, we use premium based on market values 4-week prior to the acquisition.

The use of this screen is standard in the M&A literature (e.g., Chemmanur et al. 2009). This criterion ensures that the proposed deal has a material impact on the acquirer’s future performance.

We evaluate the effectiveness of our PSM methodology by testing for mean and median differences in the matching criteria. We detect no significant difference in the variables between the test and control sample after the matching, and we therefore conclude that our PSM matching procedure is effective. We do not show the results of this matching procedure here for the sake of brevity; however they are available upon request.

The negative premium deal is therefore similar to fire-sales, where the price paid for the assets as well as prevailing market prices are below the assets best use (Eckbo and Thorburn 2008; Coval and Stafford 2007; Ang and Mauck 2011). Negative premium deals differ from fire-sales in that the former deals are not automatic as is often the case in fire-sale bankruptcy. Furthermore, a negative premium offer involves a price paid for target shares that is lower than prevailing market prices, but in fire-sales, there is no alternative for the sale of shares since the shares of firms in fire-sale are often suspended or have ceased to trade (Eckbo and Thorburn 2008).

Transaction cost economics provides a similar explanation of unrelated firm pairs and asset intangibility. Riordan and Williamson (1985) argue that the more specific the asset is to the operation at hand, the more difficult it is to price that particular asset, since the market for that asset is much less liquid. Furthermore, there may be additional costs associated with transferring assets of high specificity to alternative uses, thereby reducing the price paid by acquiring firms for target assets.

This is motivated by Moeller et al. (2004) who find that deal size is an important determinant of merger returns.

The daily price path of the negative premium target’s stock at the time of the bid announcement suggests that the market responds differently to a negative premium bid than the typical bid involving a positive premium, as the movement in the 3 days around announcement (day = −1, 0, + 1) is larger in magnitude for positive premium targets. Negative premium bids account for 3.7% of total deals during the observed period, so it is an uncommon occurrence. The smaller magnitude in the negative premium target price response may be explained by the market participants’ lack of familiarity with negative premium bids.

References

Admati AR, Pfleiderer P (2009) The “Wall Street Walk” and shareholder activism: exit as a form of voice. Rev Financ Stud 22:2645–2685. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp037

Aghion P, Tirole J (1997) Formal and real authority in organizations. J Polit Econ 105:1–29. https://doi.org/10.1086/262063

Aktas N, de Bodt E, Roll R (2010) Negotiations under the threat of an auction. J Financ Econ 98:241–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.06.002

Alexandridis G, Mavrovitis CF, Travlos NG (2012) How have M&As changed? Evidence from the sixth merger wave. Eur J Financ 18:663–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2011.628401

Almeida H, Campello M, Hackbarth D (2011) Liquidity mergers J Financ Econ 102:526–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.08.002

Amihud Y, Lev B (1981) Risk reduction as a managerial motive for conglomerate mergers. Bell J Econ 12:605–617. https://doi.org/10.2307/3003575

Andrade G, Mitchell M, Stafford E (2001) New evidence and perspectives on mergers. J Econ Perspect 15:103–120. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.2.103

Ang J, Mauck N (2011) Fire sale acquisitions: myth vs. reality. J Banking Financ 35:532–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.05.002

Ayers BC, Lefanowicz CE, Robinson JR (2003) Shareholder taxes in acquisition premia: the effect of capital gains taxation. J Financ 58:2783–2801. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1540-6261.2003.00622.x

Azar J, Schmalz MC, Tecu I (2018) Anticompetitive effects of common ownership. J Financ 73:1513–1565. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12698

Barclay MJ, Holderness CG (1989) Private benefits from control of public corporations. J Financ Econ 25:371–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(89)90088-3

Bates TW, Lemmon ML (2003) Breaking up is hard to do? An analysis of termination fee provisions and merger outcomes. J Financ Econ 69:469–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00120-X

Becht M, Polo A, Rossi S (2016) Does mandatory shareholder voting prevent bad acquisitions? Rev Financ Stud 29:3035–3067. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhw045

Bhojraj S, Sengupta P (2003) Effect of corporate governance on bond ratings and yields: the role of institutional investors and outside directors. J Bus 76:455–475. https://doi.org/10.1086/344114

Cao K, Madura J (2011) Determinants of the method of payment in asset sell‐off transactions. Financ Rev 46:643–670

Chemmanur TJ, Paeglis I, Simonyan K (2009) The medium of exchange in acquisitions: does the private information of both acquirer and target matter? J Corporate Financ 15:523–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2009.08.004

Coval J, Stafford E (2007) Asset fire sales (and purchases) in equity markets. J Financ Econ 86:479–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.09.007

Demsetz H, Lehn K (1985) The structure of corporate ownership: causes and consequences. J Polit Econ 93:1155–1177. https://doi.org/10.1086/261354.x

Denis DJ, Denis DK, Sarin A (1997) Agency problems, equity ownership, and corporate diversification. J Financ 52:135–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb03811.x

Dlugosz J, Fahlenbrach R, Gompers P, Metrick A (2006) Large blocks of stock: prevalence, size, and measurement. J Corporate Financ 12:594–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2005.04.002

Dong M, Hirshleifer D, Richardson S, Teoh SH (2006) Does investor misvaluation drive the takeover market? J Financ 61:725–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00853.x

Duggal R, Millar JA (1999) Institutional ownership and firm performance: the case of bidder returns. J Corporate Financ 5:103–117. https://doi.org/10.12691/jfe-5-5-2.x

Dyck A, Zingales L (2004) Control premiums and the effectiveness of corporate governance systems. J Appl Corporate Financ 16:51–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2004.tb00538.x

Eckbo BE, Thorburn SK (2008) Automatic bankruptcy auctions and fire-sales. J Financ Econ 89:404–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.10.003.x

Faccio M, Lasfer MA (2000) Do occupational pension funds monitor companies in which they hold large stakes? J Corporate Financ 6:71–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp070.x

Ferreira MA, Massa M, Matos P (2010) Shareholders at the gate? Institutional investors and cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Rev Financ Stud 23:601–644. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp070.x

Fich EM, Harford J, Tran AL (2015) Motivated monitors: the importance of institutional investors׳ portfolio weights. J Financ Econ 118:21–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.06.014.x

Gillan SL, Starks LT (2000) Corporate governance proposals and shareholder activism: the role of institutional investors. J Financ Econ 57:275–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00058-1.x

Goranova M, Dharwadkar R, Brandes P (2010) Owners on both sides of the deal: mergers and acquisitions and overlapping institutional ownership. Strateg M J 31:1114–1135. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.849.x

Hansen RG, Lott JR (1996) Externalities and corporate objectives in a world with diversified shareholder/consumers. J Financ Quant Anal 31:43–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/2331386.x

Harford J, Jenter D, Li K (2011) Institutional cross-holdings and their effect on acquisition decisions. J Financ Econ 99:27–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.08.008.x

He JJ, Huang J (2017) Product market competition in a world of cross-ownership: evidence from institutional blockholdings. Rev Financ Stud 30:2674–2718. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhx028.x

Holderness CG (2009) The myth of diffuse ownership in the United States. Rev Financ Stud 22:1377–1408. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhm069.x

Holland J (1998) Influence and intervention by financial institutions in their investee companies. Corporate Gov Int Rev 6:249–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8683.00113.x

Hutchinson M, Seamer M, Chapple LE (2015) Institutional investors, risk/performance and corporate governance. Int J Account 50:31–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2014.12.004.x

Jarrell GA, Poulsen AB (1989) The returns to acquiring firms in tender offers: evidence from three decades. Financ Manag 18:12–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/3665645

Konijn SJ, Kräussl R, Lucas A (2011) Blockholder dispersion and firm value. J Corporate Financ 17:1330–1339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2011.06.005

Liebeskind JP (1996) Knowledge, strategy, and the theory of the firm. Strateg M J 17:93–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171109

Matvos G, Ostrovsky M (2008) Cross-ownership, returns, and voting in mergers. J Financ Econ 89:391–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.11.004.x

McConnell JJ, Servaes H (1990) Additional evidence on equity ownership and corporate value. J Financ Econ 27:595–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(90)90069-C

Moeller T (2005) Let’s make a deal! How shareholders control impacts merger payoff. J Financ Econ 76:167–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.11.001

Moeller SB, Schlingemann FP, Stulz RM (2004) Firm size and the gains from acquisitions. J Financ Econ 73:201–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2003.07.002

Morck RK (2007) A history of corporate governance around the world: family business groups to professional managers. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Nenova T (2003) The value of corporate voting rights and control: a cross-country analysis. J Financ Econ 68:325–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00069-2

Officer MS (2007) The price of corporate liquidity: acquisition discounts for unlisted targets. J Financ Econ 83:571–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.01.004

Riordan MH, Williamson OE (1985) Asset specificity and economic organization. Int J In Or 3:365–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-7187(85)90030-X

Schwert GW (1996) Markup pricing in mergers and acquisitions. J Financ Econ 41:153–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(95)00865-C

Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1986) Large shareholders and corporate control. J Polit Econ 94:461–488. https://doi.org/10.1086/261385

Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1992) Liquidation values and debt capacity: a market equilibrium approach. J Financ 47:1343–1366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb04661.x

Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1997) A survey of corporate governance. J Financ 52:737–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04820.x

Varaiya NP (1988) The ‘winner’s curse’ hypothesis and corporate takeovers. Manag Decision Econ 9:209–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.4090090306

Weitzel U, Kling G (2018) Sold below value? Why takeover offers can have negative premiums. Financ Manag 47:421–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12200

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous referees and Cheng-Few Lee (the editor) for insightful comments and suggestions. Comments from seminar participants at the 25th Annual Global Finance Conference are also acknowledged. We are responsible for any remaining errors. Erin acknowledges financial support from the Social Sciences Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Doctoral Fellowship, Grant #752-2015-1266.

Funding

Erin Oldford, Social Sciences Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Doctoral Fellowship #752-2015-1266.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no actual or perceived conflicts of interest or competing interest to disclose.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

Variable ID | Description |

|---|---|

AssetIntangDummy | Dummy variable, equals 1 if there is target operates in high technology industry, and 0 otherwise (Cao and Madura 2011) |

BidderCompDummy | Dummy variable, equals 1 if the transaction involves more than one bidder |

CashDummy | Dummy variable, equals 1 if transaction is financed with all-cash |

CrossDummy | A dummy variable that equals one if the firm is cross-held by institutional owners in any of the four quarters in the year of the acquisition and zero otherwise |

DebtMarketLiquidity | Debt market liquidity: Commercial and industrial loans > $1 m (Officer 2007) |

EPS growth | The growth in earnings per share (EPS) from the previous year to the current year |

EquityMarketLiquidity | Equity market liquidity: IPO volume (Officer 2007) |

ICR | Interest coverage ratio = Interest expense / EBIT |

LogTA | Log of total assets for the target firm |

logTA_Bidder | Log of total assets for the bidding firm |

NegPrem | Sample deals involving a negative acquisition premium |

NumCross | The number of common institutional blockholders to the target and acquiring firm |

PosPrem | Sample deals involving a positive acquisition premium |

RelatedDummy | Dummy variable, equals 1 if there is target and bidder share the same SIC code, and 0 otherwise |

ROA | Return on assets = Net income / Total Assets |

TargetInitiatedDummy | Dummy variable, equals 1 if there is deal was initiated by the target firm (as determined by press coverage on Factiva), and 0 otherwise |

TenderOfferDummy | Dummy variable, equals 1 if the transaction is a tender offer, and 0 otherwise |

Tobin's q | Total market value of the firm / total asset value of the firm |

ToeHoldDummy | Common shares owned by acquirer at announcement |

TotalCrossOwn | The sum of the percentage of holdings of all cross-holding institutions in the sample firms (He and Huang 2017) |

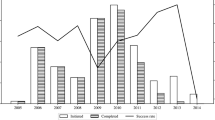

Appendix 2 Figures

See Fig. 1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oldford, E., Otchere, I. Institutional cross-ownership, heterogeneous incentives, and negative premium mergers. Rev Quant Finan Acc 57, 321–351 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-020-00946-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-020-00946-1