Abstract

Using large repeated cross-sections and a cohort-based econometric approach, this paper produces evidence that women who finish their formal education during periods of high unemployment have significantly, and persistently, lower fertility compared to women who graduate during more favorable economic conditions. In terms of magnitude, a woman who graduates into a market with a 3 percentage point higher unemployment rate experiences an approximate 14% reduction in birth probabilities about a half-decade later. The long-recognized negative effects of unemployment on marriage explain, at most, 30% of that reduction in fertility. Rather, graduating into high unemployment appears to exert its own influence on fertility, separate from its effect on marriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Fertility in the U.S. increasingly shows procyclical patterns related to business cycles (Coskun & Dalgic, 2024). A related concern is whether, during economic downturns, decreases in fertility represent permanant reductions or simple delays in child bearing. Seltzer (2019) argues that such effects are persistent, because recessions bring about structural changes in labor markets that, themselves, tend to be persistent. Buckles et al. (2024), focusing specifically on the Great Recession, offer evidence that a reduction in unintended births accounted for about two-thirds of the drop in fertility following that particular economic downturn. They also find that unintended births remained depressed in the years that followed, primarily due to changes in demographics, reductions in sexual activity, and shifts in contraceptive methods.

This paper, using different methods and data sources, reaches similar conclusions. In terms of magnitude, the paper finds that a woman who graduates into a market with a 3 percentage point higher unemployment rate experiences an approximate 14% reduction in birth probabilities about a half-decade later. Those reduced birth probabilities do not appear to be due to delayed child bearing; rather, fertility appears to remain permanently depressed for women graduating into higher unemployment.

That finding comes from an econometric “scarring model” that uses large cross-sectional surveys and focuses on state-level cohorts by graduation year. Using a similar econometric approach, this paper also demonstrates that the same is true for marriage, with women graduating during periods of high employment also being significantly, and persistently, less likely to marry. Of course, marriage, itself, is an important determinant of fertility. Thus, an obvious follow-up question is: Does graduating into high unemployment directly lower fertility, or does graduating into high unemployment reduce marriage, which then, in turn, hinders fertility? If lawmakers wish to enact policies aimed at boosting fertility, then the answer to that question has important implications for how those policies should be structured and targeted.

In an attempt to untangle those interconnected parts, this paper turns to a mediation analysis (Baron & Kenny, 1986), an approach that has seen growing popularity in the applied statistical literature. Results from that exercise suggest that, following periods of high unemployment, lower marriage rates explain, at most, 30% of lower fertility. Rather, graduating into high unemployment appears to exert its own influence on fertility, separate from its effect on marriage.

That conclusion has important implications for policymakers who might wish to encourage fertility. For example, findings of this paper suggest that, following periods of high unemployment, marriage-friendly policies, by themselves, might not yield large boosts to fertility. Rather, graduating into high unemployment appears to bring with it persistent economic scarring, and thus fertility might recover only by offering assistance that directly reduces the costs of bearing children, such as favorable tax treatment or subsidized child care.

2 Background

Rodríguez et al. (2020) review the many harmful individual-level effects of graduating into a recession. In addition to earnings and family formation, graduating into recessions might cause reductions in life expectancy and increased mortality. Graduating into recessions also appears to contribute to unhealthy lifestyle practices.

Turning to the main focus of this paper, social scientists, dating at least to studies by Galbraith and Thomas (1941) and Silver (1965), have sought to explore links between economic conditions and fertility. That early generation of studies primarily focused on quantifying historical correlations between business cycles, marital rates, and births. As developed nations continued to become richer, a curious pattern emerged, characterized by an inverse relationship between income and fertility, both at the micro and macro levels. Becker (1960) marked a turning point and ushered in a new generation of studies seeking to explain why income relates to lower fertility. Much of that literature settled on rising female labor force participation, and its attendant deleterious effects on fertility, as a central explanation for the inverse link between income and fertility (Hotz et al. 1997).

Since around 1980, however, that inverse relationship between income and fertility has vanished, and in some cases slightly reversed, at least among developed countries. Doepke et al. (2022) provide a survey of the various theories that seek to explain that reversal. Many of the explanations point to policies that have been implemented in developed nations that attempt to ease the ability of women to raise children while simultaneously pursuing careers. Examples include flexible work arrangements and favorable tax treatment of childcare.

Lending credence to those suppositions, Fig. 1 shows trends in fertility and marital status calculated from the American Community Survey. Note that here and throughout the remainder of this paper, fertility refers to live births, which necessarily ignores abortions, still births, and miscarriages. The largest drop in fertility appears to have occurred amongst younger women. Other age groups appear less impacted. Meanwhile, marital rates appear to be decreasing across all age groups. Those changes in fertility and marital status have coincided with continued increases in female educational attainment, as evidenced in Fig. 2.

A much smaller strand of research focuses specifically on the link between unemployment and fertility. Adsera (2005) argues that economic theory points to ambiguous links between the two. On one hand, a short unemployment spell brings with it a fall in opportunity costs of child bearing, thus possibly increasing fertility. However, she argues that a persistent unemployment spell actuates a potentially large income penalty, which in turn might reduce fertility, especially if parents count children as “normal goods.” Corroborating her prediction of ambiguous effects, some studies find countercyclical effects, characterized by higher unemployment leading to increased fertility (Butz & Ward, 1979; Ermisch, 1980; Ermisch, 1988), but a larger number of studies find procyclical patterns (Macunovich, 1996; Adsera, 2004; Sobotka et al., 2011; Bono et al., 2015; Schneider, 2015; Schaller, 2016; Raymo & Shibata, 2017; Karaman Örsal & Goldstein, 2018; Bellido & Marcén, 2019; Buckles, Guldi, & Schmidt, 2024). Adding more nuance to procyclical findings, Buckles, Hungerman, and Lugauer (2021) argue that, due to the approximate 9-month duration between conception and birth, a fall in conceptions might portend forthcoming economic decline.

The closest study to this paper is Currie and Schwandt (2014). Their emphasis differs somewhat from what appears in this paper, in that they focus on the effects of unemployment at various stages of child bearing years, whereas this paper emphasizes the economic climate into which women graduate. Nonetheless, they, too, find procyclical fertility patterns using a cohort-based analysis.

3 Data

Research in labor economics offers several examples of “scarring” models, which seek to investigate the long-run damage of experiencing negative economic circumstances (Oreopoulos et al., 2012; Schwandt & Von Wachter, 2019; Rothstein, 2023). The empirical approach employed in this paper offers a version of such a model. Specifically, this paper seeks to explore a relationship characterized by

where yi,t is a measure of fertility for woman i in year t, and ui,0 is the unemployment rate in the state in which she resided when she finished her formal schooling. In an ideal setting, the coefficient β would give the causal effect of unemployment on subsequent fertility. The form of the actual econometric setup attempts to mimic that ideal regression in light of the types of information commonly available in large household surveys. For that reason, the data sources are discussed before turning to details of the estimation approach.

Person-level information comes from repeated annual waves of the American Community Survey (ACS), conducted and published by the U.S. Census Bureau. Containing nationally-representative information usually available only in the long form of the decennial census, the ACS represents the largest household survey administered by the Census Bureau. Data used in this study come from the annual waves of the survey from the years 2000, 2001, …, 2019. The estimation sample includes all women who, during their ACS interview, were between the ages 16 and 45, and who reported at least a 9th grade education. The sample considers only women born in one of the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia.

An important disadvantage of the ACS is that it does not record when a person finishes her formal education. Following the literature (Schwandt and Von Wachter 2019), this paper sidesteps that data limitation by forming, for every woman, a “Mincerian” year of graduation, defined as birth year, plus 6, plus years of reported education. Because of the years of the ACS cross sections, and the ages of the women under consideration, the Mincerian graduation years cover 1985 to 2019. (The Mincerian year of completion is hereafter referred to as the “graduation year”).

Another disadvantage of the ACS is that it does not record the state in which the person resided during her graduation year, which precludes a perfect match of women to their graduation year unemployment rates. This paper proxies for that information using the unemployment in the woman’s graduation year in her current state of residence, but that opens the possibility of bias owing to endogenous migration. If, for example, women seeking to have children migrate to locations with more favorable economic conditions, then such migration patterns will attenuate the observed link between unemployment and fertility. A frequent concern among cohort-based studies that use census data, this paper explores the extent of endogenous migration by also considering a subsample of women who, during the year of their ACS interview, reported living in the same states in which they were born. Results from that subsample of non-migrators produce estimates that are nearly identical to those obtained from the larger baseline estimation sample.

Another concern is the possible endogenous termination of education. That is, although this paper’s main concerns are fertility patterns after a woman completes her education, she could end her education because of pregnancy or marriage. While the impacts of pregnancy and marriage on early termination of education represent important policy concerns, they are not the main focus of this paper. Thus, to reduce the possibility of endogenously-terminated education, the estimation sample deletes women who gave birth or became married in their first year after their Mincerian completion year. Finally, the estimation sample focuses on women no more than 15 years removed from their graduation year, as those are likely the most important years for family formation and fertility.

Those sample restrictions yield 5,046,772 unique women, with sample means reported in Table 1. The top of the table reports the main outcome of interest. Rather than number of children ever born, the ACS records whether the woman gave birth during the past year. Meanwhile, marital status is captured by a dichotomous indicator for whether the subject is currently married. The table also reports four education groups, which are constructed from the graduation year. The table also reports race. (The education and race numbers appear to align with national averages reported by the U.S. Census during those years).

Following the practice of other cohort-based studies, those more than 5 million data points are aggregated at the level of (1) current state of residence, (2) calendar year, (3) graduation year, and (4) education group. Such a cell-based approach suffices because the empirical analysis does not use individual-level controls, and it reflects that the main source of variation in the treatment variable (unemployment rate) occurs at the state/year level. The final cell-based sample size includes 64,266 observations. That final estimation sample includes the main treatment variable of interest, the state-level unemployment rate during the cell’s year of graduation, available from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

4 Econometric model

The scarring model takes the form of a linear regression

where \({\overline{y}}_{s,t,g,e}\) represents mean fertility at the cell level. The four subscripts index current state of residence (s), calendar year (t), graduation year (g), and education group (e). The regression also includes fixed effects for years since graduation (z). The treatment variable of interest, us,g, is the unemployment rate in state s during graduation year g. With the dependent variable measured as means, and with different numbers of observations giving rise to those means, all estimates reported below analytically weight by cell size. Moreover, all standard errors account for clustering at the state level. (Different clustering levels did not appear to alter the main conclusions).

The inclusion of fixed effects for calendar year, graduation year, and differences between the two allows the coefficient attached to us,g to isolate the effects of differences in unemployment rates. For example, large “years since graduation” necessarily pertain to older women who graduated in earlier years. Thus, the coefficients β5 and β15 apply to different sets of women. However the various fixed effects absorb variation from those factors, allowing the regression to isolate the main relationship of interest.

Relatedly, as indicated by the subscript attached to the main coefficient of interest, βz, the effect of unemployment on fertility is permitted to evolve as the woman becomes further removed from her year of graduation. In light of the included fixed effects, those coefficients capture cohort/state-specific deviations from the “typical” evolution of how fertility responds to variation in graduation-year unemployment.

5 Main findings

Figure 3 plots the effects of the state unemployment rate during the year of graduation on the probability of having given birth in the past year. The dots in the figure represent the coefficients βz in equation (1), and the dashed lines provide a 95% confidence band based on the estimated standard errors, which adjust for clustering at the state level. (Recall that, in order to reduce the possibility of endogenously-terminated education, the estimation sample does not include women who gave birth or married during the first year after their graduation year. For that reason, the effects reported in the figure start two years after graduation).

The effect of unemployment on fertility. Dots represent the coefficients βz in equation (1). Dashed lines provide 95% confidence band

The figure shows that a higher unemployment rate during the year of graduation is associated with an immediate reduction in fertility that persists for about 9–10 years. After that, the effect of graduation year unemployment becomes statistically insignificant, but note that it never turns positive. Thus, because each point in the figure shows the effect on one-year fertility, the overall implication is that a woman’s lifetime fertility shrinks as a consequence of higher graduation-year unemployment.

Table 2 shows regression estimates from equation (1) where to keep the table from becoming unwieldy, the years-since-graduation measure is aggregated into groups. Focusing on the full sample, graduation-year unemployment appears to exert a nearly immediate impact on fertility, with that effect growing in magnitude over time. Approximately 4–6 years after graduation, a 3 percentage point increase in unemployment – the approximate increase peak-to-trough during a recession – reduces the probability of having given birth in the past year by about 1.4 percentage points (3 × 0.0048). Compared to the mean of the dependent variable (0.10), that 1.4 percentage point decrease represents an approximate 14 percentage decrease in fertility. That decrease in fertility remains 7–9 years after graduation, after which it becomes insignificant, but never turns positive.

The remainder of Table 2 considers various subsamples of potential policy interest. Nonwhites who graduate into higher unemployment appear to experience larger initial reductions in fertility. By 4–6 years after graduation, magnitudes appear similar to those obtained from the full sample, after which they become statistically insignificant. A somewhat similar pattern emerges amongst women with no high school degree, with the effects being quite pronounced up to 6 years after finishing school, but insignificantly distinguishable from zero after that. At the far extreme, college-educated women show little immediate impact, but unemployment does appear to hinder their fertility 4–9 years after graduating. Curiously, college-educated women show a positive effect of graduation-year unemployment on fertility 13–15 years after graduating. (Though, in a table with 30 reported coefficients, the presence of a Type I error would not be surprising).

Returning to the full sample, the main results presented in Fig. 3 include fixed effects for education groups. Figure 4 presents estimates for each of the education groups estimated separately (not including the confidence bands to avoid clutter). Although all education groups appear to suffer fertility reductions in the wake of higher unemployment, the effect appears largest amongst women with less than a high school education. (See Johnson, (2013) for an analysis of the nuanced links between educational attainment and economic conditions).

The effect of unemployment on fertility. Partitioned by education group. Dots represent the coefficients βz in equation (1).

As mentioned in the Data section, if women who seek to have children move to locales with more favorable economic conditions, then that sort of endogenous migration might introduce attenuation bias. As a check, equation (1) was reestimated on a subsample of women who, during the year of their ACS interview, reported living in the same state in which they were born. Although focusing on non-migrators might push the bias in the opposite direction, the estimates reported in Fig. 5 look nearly identical to those reported in Fig. 3.

The effect of unemployment on fertility. Subsample of non-migrators. Dots represent the coefficients βz in equation (1). Dashed lines provide a 95% confidence band

That finding appears to align with other cohort-based studies that fail to detect evidence of endogenous migration (Schwandt and Von Wachter 2019). Consequently, the remainder of this paper focuses on the full sample of women.

Figure 6 repeats the analysis presented in Fig. 3 (including migrators) but partitions the sample into 5-year windows in an attempt to explore whether the effects of unemployment on fertility are changing over time. The estimates appear to suffer loss of precision, especially during the 2010-2014 periods, perhaps owing to the smaller sample sizes used to generate each picture. That concern notwithstanding, the relationship between unemployment appears to remain relatively constant across the 20 years under consideration.

During the years under consideration, the Great Recession stands out as a time of particularly severe economic hardship. Consequently, an obvious follow-up topic of exploration is what effects, if any, the Great Recession had on fertility. Doing proper justice to that topic likely warrants its own study. But as an abbreviated investigation, equation (1) is reestimated after removing us,g and shifting focus to the graduation year cohort fixed effects ηg. This is a modified version of the method used by Rothstein (2023) to study the effects of the Great Recession on employment outcomes.

Those cohort fixed effects, plotted in Fig. 7, suggest that women who graduated during the Great Recession, which reached its nadir in 2009, exhibited reduced fertility. Curiously, that effect, while evident in the graph, was larger in magnitude and more statistically significant for women who graduated several years after the Great Recession, suggesting that that particular economic calamity took several years to fully affect fertility. That finding somewhat aligns with Buckles, Guldi, and Schmidt (2024), who offer evidence that the Great Recession induced a relatively persistent negative effect on fertility.

Fertility by graduation cohorts. Dots represent the estimates ηg in equation (1) after omitting us,g. Dashed lines provide 95% confidence band

6 The mediating role of the marriage of income

Figure 3 shows the total effect of graduation-year unemployment on subsequent fertility, represented in the following schematic drawing.

But does there exist a confounding factor that contributes to that total effect? Perhaps high unemployment during a person’s year of graduation hinders her subsequent marital prospects, which, in turn, lowers future fertility.

Taking the regression model in equation (1) and replacing the dependent variable with the cell-level mean for being currently married, one arrives at Fig. 8. Higher graduation-year unemployment appears to be associated with immediate and persistent reductions in probabilities of being married during subsequent years. The largest effects appear to occur 4-6 years after graduation, when a 3 percentage point increase in graduation-year unemployment reduces marriage probabilities by about 4 percentage points (3 × 0.0133). Relative to the mean of the dependent variable (0.37), that reduction translates to an approximate 11% decrease in marital probabilities. That effect starts to shrink about 5 years after graduation but remains statistically significant more than a decade after graduation.

The finding that unemployment hinders marital prospects corroborates earlier research (Schaller, 2013), but it appears to conflict with Schwandt and Von Wachter (2019), who find a null effect of recessions on subsequent marriage. It should be noted, however, that their data blends both genders and more importantly, includes years dating to the mid-1970s, a time before some recent trends in fertility and marital status.

In terms of this paper, that finding raises a question of mediating effects. That is, is the negative influence of graduation-year unemployment on fertility really a true direct effect? Or does that reduction in fertility actually reflect the deleterious effects of graduation-year unemployment on marriage. And if one filters out those effects on marriage, would any effects on fertility remain? Mediation analysis (Baron & Kenny, 1986) offers an ideal channel through which to address those questions.

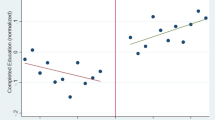

Mediation analysis seeks to isolate the bottom arrow, labeled the “direct effect,” after filtering the mediating influence of unemployment on marriage. (It should be noted, however, that the term “direct” used in mediation analysis does not imply that the relationship has been scrubbed of all potential confounding factors. Rather, the term indicates that the relationship has been scrubbed of the confounding factor under consideration, in this case, marriage.) The algorithm, which is essentially a series of cross-regression hypotheses tests, is implemented using Stata’s gsem suite of estimators. (That suite also allows for analytical weights and clustered standard errors, as in the baseline scarring model presented above Fig. 3). Figure 9 presents mediation results.

The effect of unemployment on marriage. Dots represents the coefficients βz in equation (1). Dashed lines provide 95% confidence band

The solid line repeats Fig. 3, but without the confidence band in order to avoid clutter. The dashed line provides the “direct effect” after filtering out the role of marriage. The differences between those two lines are highly statistically significant at every “year since graduation”. But statistical significance notwithstanding, the mediating role of marriage appears to be quantitatively small.

As an example, focusing on 5 years since graduation, a point at which all effects appear to be near their peaks, the total effect of unemployment on fertility is approximately − 0.0051. Removing the mediating influence of marriage shrinks that effect to approximately − 0.0035. That is, the mediating influence of marriage, at its peak, accounts for only about 30% of the total observed effect.

Another potential confounding factor is subsequent income. Graduating into higher unemployment has been shown to lead to lower income (Schwandt & Von Wachter, 2019). Could lower income, rather than unemployment itself, be the root cause of lower fertility? Figure 10 repeats the mediation exercise after replacing marital status with mean cell-level family income. Evidently, although subsequent income is a statistically significant mediating factor, its magnitude is rather small.

7 Evidence from the CPS

The Current Population Survey (CPS) records much of the same information that exists in the ACS. This paper prefers the ACS because it produces much larger sample sizes. Furthermore, the CPS fertility measures are recorded only every other year, necessitating a consideration of biennial, as opposed to annual, periodicity. Nonetheless, the CPS serves as a useful tool to explore robustness, in part because of its different survey methodology. But also, in constrast to the ACS, which records fertility according to whether a woman has given birth in the past year, the CPS records the total children ever born.

To that end, the main analyses reported above are repeated using a sample of women drawn from the CPS using the exact same sample restrictions discussed in Section 3. Whereas the ACS sample contained 5,047,772 women collapsed to 64,266 cells, the CPS contains 422,013 women collapsed to 31,184 cells.

Figure 11 shows the effect of unemployment on fertility from the CPS sample. Similar to Fig. 3 from the ACS, graduating into higher unemployment leads to reductions in fertility peaking about a half decade later, though the smaller number of cells (and the smaller number of data points used to create each cell) yields noisier, and less precise, estimates. Because the CPS fertility variable measures the number of children ever born, the effects remain persistently negative.

The effect of unemployment on fertility. Dots represent the coefficients βz in equation (1). Dashed lines provide 95% confidence band

Figure 12 repeats the mediation exercise. Similar to Fig. 9 for the ACS, the effect of unemployment on marriage appears to be part of the story, but the larger relationship appears to be a “direct” effect of unemployment on fertility.

Thus, results from the CPS appear to corroborate estimates obtained from the larger baseline ACS sample, suggesting that the paper’s main punchlines do not stem from quirks present in any particular survey.

8 Conclusion

This paper provides evidence that women who graduate into higher unemployment show large and persistent reductions in fertility. In terms of magnitude, a 3 percentage point higher unemployment rate during a woman’s year of graduation leads to an approximate 14% reduction in birth probabilities about a half decade later. Those probabilities never turn positive, implying a permanent drop in fertility.

Researchers have long been aware that negative economic conditions also tend to hinder marriage rates. Yet, a mediation exercise suggests that, of the aforementioned drop in fertility, at most 30% of that drop is explained by lower rates of marriage. Moreover, a mediation exercise also suggests that, while graduating into higher unemployment reduces future earnings, the mediating effect of earnings on fertility, while statistically significant, is quantitatively small. However, the paper does not explore an exhaustive set of potential mediating factors. General economic uncertainty or negative news events could, possibly, impact both unemployment and fertility. That caveat notwithstanding, the results appear to point toward a direct link between unemployment and fertility.

In the most closely-related study to this one, Currie and Schwandt (2014) find that higher unemployment at ages 20-24 leads to permanently lower fertility. This paper reaches (somewhat) similar conclusions while focusing on the economic climate into which women graduate. Taken together, a follow-up question is whether it is actually graduating into high unemployment that hinders fertility, or it is being approximately graduation-age during a period of high unemployment. Unscrambling that puzzle likely warrants its own study, but from a policy perspective, the distinction probably does not matter significantly.

Thus, if lawmakers wish to implement policies aimed at encouraging fertility, then these results suggest that policies targeting marriage would be only partially effective. Instead, at the risk of ignoring biological and emotional elements of fertility, if prospective mothers face downward-sloping demand curves for children, then lawmakers should directly target the “price” of having children. Such policies might include financial assistance for neonatal medical services and subsidized daycare.

References

Adsera, A. (2004). Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labor market institutions. Journal of Population Economics, 17(1), 17–43.

Adsera, A. (2005). Vanishing children: From high unemployment to low fertility in developed countries. American Economic Review, 95(2), 189–193.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Becker, G. S. (1960) An economic analysis of fertility. Demographic and economic change in developed countries. In NBER conference series (Vol. 11, pp. 209–231).

Bellido, H., & Marcén, M. (2019). Fertility and the business cycle: the European case. Review of Economics of the Household, 17(4), 1289–1319.

Bono, E. D., Weber, A., & Winter-Ebmer, R. (2015). Fertility and economic instability: The role of unemployment and job displacement. Journal of Population Economics, 28(2), 463–478.

Buckles, C., Guldi, M. and Schmidt, L. (2024). The Great Recession’s baby-less recovery: the role of unintended births. Journal of Human Resources, forthcoming 59(S).

Buckles, K., Hungerman, D. & Lugauer, S. (2021). Is fertility a leading economic indicator? The Economic Journal, 131(634), 541–565.

Butz, W. P., & Ward, M. P. (1979). The emergence of countercyclical US fertility. The American Economic Review, 69(3), 318–328.

Coskun, S. & Dalgic, H. C. (2024). The emergence of procyclical fertility: The role of breadwinner women. Journal of Monetary Economics, 142, 1–21.

Currie, J., & Schwandt, H. (2014). Short-and long-term effects of unemployment on fertility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(41), 14734–14739.

Doepke, M., Hannusch, A., Kindermann, F. and Tertilt, M. (2022). A new era in the economics of fertility. VoxEU. org, 11.

Ermisch, J. F. (1980). Time costs, aspirations and the effect of economic growth on German fertility. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 42(2), 125–143.

Ermisch, J. (1988). Econometric analysis of birth rate dynamics in Britain. The Journal of Human Resources, 23(4), 563–576.

Galbraith, V. L., & Thomas, D. S. (1941). Birth rates and the interwar business cycles. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 36(216), 465–476.

Hotz, V. J., Klerman, J. A., & Willis, R. J. (1997). The economics of fertility in developed countries. Handbook of Population and Family Economics, 1, 275–347.

Johnson, M. T. (2013). The impact of business cycle fluctuations on graduate school enrollment. Economics of education review, 34, 122–134.

Karaman Örsal, D. D., & Goldstein, J. R. (2018). The changing relationship between unemployment and total fertility. Population Studies, 72(1), 109–121.

Macunovich, D. J. (1996). Relative income and price of time: Exploring their effects on US fertility and female labor force participation. Population and Development Review, 22, 223–257.

Oreopoulos, P., Von Wachter, T., & Heisz, A. (2012). The short-and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(1), 1–29.

Raymo, J. M., & Shibata, A. (2017). Unemployment, nonstandard employment, and fertility: Insights from Japan’s “Lost 20 Years”. Demography, 54(6), 2301–2329.

Rodríguez, J., Colston, J., Wu, Z. and Chen, Z. (2020). Graduating during a recession: A literature review of the effects of recessions for college graduates. Center for Research on CollegeWorkforce Transitions (CCWT), University of Wisconsin Madison.

Rothstein, J. (2023). The lost generation? Labor market outcomes for post-great recession entrants. Journal of Human Resources, 58(5), 1452–1479.

Schaller, J. (2013). For richer, if not for poorer? Marriage and divorce over the business cycle. Journal of Population Economics, 26, 1007–1033.

Schaller, J. (2016). Booms, busts, and fertility testing the Becker model using gender-specific labor demand. Journal of Human Resources, 51(1), 1–29.

Schneider, D. (2015). The great recession, fertility, and uncertainty: Evidence from the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(5), 1144–1156.

Seltzer, N. (2019). Beyond the Great Recession: Labor market polarization and ongoing fertility decline in the United States. Demography, 56(4), 1463–1493.

Silver, M. (1965). Births, marriages, and business cycles in the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 73(3), 237–255.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 267–306.

Schwandt, H., & Von Wachter, T. (2019). Unlucky cohorts: Estimating the long-term effects of entering the labor market in a recession in large cross-sectional data sets. Journal of Labor Economics, 37(S1), S161–S198.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z. conducted all analyses, wrote the main text, and prepared all tables and figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zimmer, D.M. The long-run effects of recessions on fertility. Rev Econ Household (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-024-09713-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-024-09713-w