Abstract

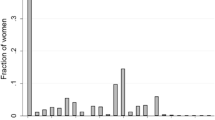

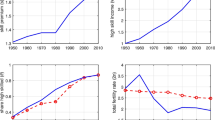

Fertility rates have long been falling in many developed countries, while educational attainment in those countries has risen. We attempt to reconcile these two trends with a novel application of two recent models to generate plausibly causal effects of education that can explain these decreases in fertility. Using Canadian data, we exploit changes in compulsory schooling laws to find that education “compresses” the fertility distribution—women are more likely to have at least one child but less likely to have multiple children. We demonstrate that the mechanism for this effect is the positive impact of education on earnings and marriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

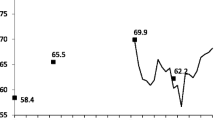

In the USA, total fertility decreased from about 3.5 children per woman in 1960 to roughly 2.0 children in 2010, while Canada saw a decline in total fertility from 3.9 children in 1960 to 1.6 in 2010. In England and Wales, the comparable rates are 2.7 in 1960 and 1.9 in 2010; in Ireland, 3.8 in 1960 and 2.1 in 2010; in Finland, 2.7 in 1960 and 1.9 in 2010; in the Netherlands, 3.1 in 1960 and 1.8 in 2010; in Italy, 2.4 in 1960 and 1.5 in 2010; in France, 2.9 in 1960 and 2.0 in 2010; in Germany, 2.4 in 1960 and 1.4 in 2010.

For example, fertility among American women aged 40 to 50 years old in 2012 varied substantially by educational attainment—from about 2.6 for those with less than a HS degree to about 1.8 for women with a bachelor’s degree and 1.7 for those with a graduate or professional degree. Moreover, while just less than 12% of those with less than a high school degree were childless, nearly one-quarter of women with a graduate or professional degree had no children when surveyed.

Despite the high degree of within-country similarities when it comes to education, Canada is a linguistically diverse country with a large number of Francophone citizens in addition to the larger English-speaking group. Such differences suggest potential heterogeneous impacts of education on fertility, but since most Francophones reside in one province (Quebec) and since the variation in compulsory schooling we exploit is at the provincial level, we can not validly assess such differences.

CSLs appeared in British Columbia shortly afterward, in 1873, with most Canadian provinces enacting them by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century.

The deference shown to rural areas, mostly based on their agrarian nature and extensive use of child labor, is also apparent in the Adolescent School Attendance Act of 1921, whereby Ontario increased the compulsory age of attendance from 14 to 16 years old, but only for young adults living in urban areas. Perhaps not surprisingly, newly required 14 and 15 year olds were exempted from the law if they were employed at home or for wages, and if they possessed a parent-endorsed “certificate of employment,” which exempted youth from minimum school leaving laws, were often obtained by passing equivalency tests, typically at the level of grade 7 or 8, but sometimes merely tested basic skills like reading or writing. These young adults were still required to attend part-time instruction in the evenings, where such classes existed.

It should be noted that more recent models such as Galor (2012) have identified some shortcomings within these models, but the discussion of this work provides context for more recent papers within this review.

Becker et al. (1990) develop a theoretical model to demonstrate that, in the context of economic growth and development, increased investment in educational attainment may lead to equilibrium with smaller families—directly in accordance with the quantity-quality model.

It should be noted that Galor (2012) has argued that the tests of the quantity-quality trade-off within the Beckerian model can be questioned because of flawed assumptions within the theoretical model. We discuss these results for context.

McCrary and Royer (2011) also find no relationship between such education and child health, which again is the focus of their study.

Unlike ALM, we do not examine the fertility of a cohort of parents.

While we acknowledge that CSL-induced education may impact the desired fertility of males in ways that may, in turn, impact the effect of such increases in education on women’s actual fertility, which is our ultimate question of interest, we follow Aaronson et al. (2014) and focus only on women’s behavior in our model and in our ultimate empirical analysis.

The confidential data sets were only accessible through secure sites and contained information not collected for the publicly-available extracts of the decennial censuses. In particular, the confidential files contain specific information about earnings in the prior year, as well as specific amounts of education obtained by the household member and an individual’s exact date of birth.

A Canadian “province” is analogous to an American state. There are ten provinces in Canada and three territories; the sample analyzed within this study will include only data drawn from individuals born in one of the ten provinces.

In particular, the analysis was replicated with a cut-off age of 42 and 44, and the results are essentially the same as will be reported.

Information on the specific timing for changes in these laws is presented in Appendix Table 6. Note that we assign all CSL measures so that they correspond to when a woman is of usual school age.

For more detail, see Angrist et al. (1996).

More accurately, since we use longitudinal data, the concern is whether changes in the instrument are uncorrelated with changes in factors in the error term that might independently affect fertility-related outcomes.

A more formal analysis of the trends reveals that: there is a statistically significant shift in the trend line in Fig. 1 after the law change; the slope trend line is statistically significant prior to the law change, but not statistically significant after the law change, and; the slope of the trend line is not statistically significant before the law change, but is statistically significant after the law change. The regressions that underlie these results are available upon request.

The fact that we are estimating local average treatment effects which estimate the impact of additional education on those induced to comply with compulsory schooling laws may also drive these seemingly large results. Indeed, to extrapolate to the entire population would involve multiplying the coefficients in question by the fraction of the population impacted by compulsory schooling laws (roughly 20% of our sample) as well as their average effect on educational attainment (between roughly 0.5 and 0.9 years).

We test the ZIP specification against a standard count-data model with a Vuong test, and the results reject the standard Poisson model in favor of the ZIP model.

We thank an anonymous referee for raising this possibility.

References

Aaronson D, Lange F, Mazumder B (2014) Fertility transitions along the extensive and intensive margins. Am Econ Rev 104(11):3701–3724

Aaronson D, Mazumder B (2011) The impact of Rosenwald Schools on black achievement. J Polit Econ 119(5):821–888

Angrist JD et al (1996) Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc 91(434):444–455

Angrist JD, Lavy V, Schlosser A (2010) Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. J Law Econ 28(4):773–824

Axelrod P (1997) The Promise of schooling: education in Canada, 1800-1914. University of Toronto Press

Baudin T, de la Croix D, Gobbi PE (2015) Fertility and childlessness in the United States. Am Econ Rev 105(6):1852–1882

Becker GS (1960) “An economic analysis of fertility”. Demographic and economic change in developed countries. Princeton, National Bureau of Economic Research, pp 209–231

Becker GS (1965) A theory of the allocation of time. Econ J 75(299):493–517

Becker et al (2010) The effect of investment in children's education on fertility in 1816 Prussia. Cliometrica 6(1):29–44

Becker GS, Gregg Lewis H (1973) On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 81(2 Part 2):S279-288

Becker GS, Murphy KM, Tamura R (1990) Human capital, fertility, and economic growth. J Polit Econ 98(5 Part 2):S12–S37

Becker GS and Tomes N (1976) Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 84(4), part 2:S143–S162

Bhalotra S, Venkataramani A, Walther S (2019) “Fertility and labor market responses to reductions in mortality”. working paper

Bianchi SM (2011) Family change and time allocation in American families. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 638(1):21–44

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2005) The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Quart J Econ 120(2):669–700

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2010) Family size and the IQ scores of young men. J Hum Resour 45(1):33–58

Bleakley H, Lange F (2009) Chronic disease burden and the interaction of education, fertility, and growth. Rev Econ Stat 91(1):52–65

Caceres-Delpiano J (2006) The impacts of family size on investment in child quality. J Hum Resour 41(4):738–754

Cameron AC et al (2008) Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Rev Econ Stat 90(3):414–427

Cameron AC, Miller DL (2015) A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. J Hum Resour 50(2):317–372

Cooksey EC, Fondell MM (1996) “Spending time with his kids: effects of family structure on fathers’ and children’s lives. J Marriage Fam 58(3):693–707

Cygan-Rehm K and Maeder M (2013) The effect of education on fertility: evidence from a compulsory schooling reform. Labour Econ 25(C):35–48

Dickson M et al (2016) Early, late or never? When does parental education impact child outcomes? Econ J 126(596):F184–F231

Davidson R, MacKinnon JG (2010) Wild bootstrap tests for iv regression. J Bus Econ Stat 28(1):128–144

Devereux PJ, Hart RA (2010) Forced to be rich? Returns to compulsory schooling in Britain. Econ J 120(549):1345–1364

Echevarria E, Merlo A (1999) Gender differences in education in a dynamic household bargaining model. Int Econ Rev 40(2):265–286

Fernihough A (2017) Human capital and the quantity-quality tradeoff during the demographic transition. J Econ Growth 22(1):35–65

Fort M et al (2016) Is education always reducing fertility? Evidence from compulsory schooling reforms. Econ J 126:1823–1855

Galor O (2012) The demographic transition: causes and consequences. Cliometrica 6(1):1–28

Galor O, Moav O (2002) Natural selection and the origin of economic growth. Quart J Econ 117(4):1133–1191

Galor O, Weil DN (2000) Population, technology, and growth: from Malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond. Am Econ Rev 90(4):806–828

Gobbi PE (2018) Childcare and commitment within households. J Econ Theory 176(C):503–551

Hanushek EA (1992) The trade-off between child quantity and quality. J Polit Econ 100(1):84–117

Hungerman D (2014) The effect of education on religion: Evidence from compulsory schooling laws. J Econ Behav Organ 104(C):52–63

Katz MS (1976) A history of compulsory education laws. Fastback Series, No. 75. Bicentennial Series

Kessler D (1991) Birth order, family size, and achievement: family structure and wage determination. J Law Econ 9(4):413–426

Kendig S, Bianchi SM (2008) Single, cohabiting and married mothers’ time with children. J Marriage Fam 70(5):1228–1240

Klemp M, Weisdorf J (2019) Fecundity, fertility and the formation of human capital. Economic Journal 129(February):925–960

Lavy V, Zablotsky (2015) Women's schooling and fertility under low female labor force participation: Evidence from mobility restrictions in Israel. J Public Econ 124(C):105–121

Lee J (2008) Sibling size and investment in children’s education: an Asian instrument. J Popul Econ 21(4):855–875

Leon A (2004) The effect of education on fertility: evidence from compulsory schooling laws. Mimeo

Li H, Zhang J, Zhu Yi (2008) The quantity-quality trade-off of children in a developing country: identification using Chinese twins. Demography 45(1):223–243

Lucas AM (2013) The impact of malaria eradication on fertility. Econ Dev Cult Chang 61(3): 607–631

McCrary J, Royer H (2011) The effect of female education on fertility and child health: evidence from school entry policies using exact date of birth. Am Econ Rev 101(1):158–195

Monstad K et al (2008) Education and fertility: evidence from a natural experiment. Scand J Econ 110(4):827–852

Murphy T (2015) Old habits die hard (sometimes). J Econ Growth 20(2):177–222

Oreopoulos P (2005) “Canadian compulsory schooling laws and their impact on educational attainment and future earnings”, Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper, No. 521, Statistics Canada

Oreopoulos P (2006a) Estimating average and local average treatment effects of education when compulsory schooling laws really matter. Am Econ Rev 96(1):152–175

Oreopoulos P (2006b) The compelling effects of compulsory schooling. Can J Econ 39(1):22–52

Oreopoulos P et al (2006) The intergenerational effects of compulsory schooling. J Labor Econ 24(4):729–760

Qian N (2017) Quantity-quality and the one-child policy: the only-child disadvantage in school enrollment in rural China. Forthcoming, Gender and Development

Pencavel J (1998) The market work behavior and wages of women: 1975–94. J Hum Resour 33(4):771–804

Pischke JS, von Wachter T (2008) Zero returns to compulsory schooling in Germany: Evidence and interpretation. Rev Econ Stat 90(3):592–598

Phillips CE (1957) The development of education in Canada. Gage, Toronto

Rosenzweig MR, Schultz TP (1980) Fertility and investments in human capital: estimates of the consequence of imperfect fertility control in Malaysia. J Econ 48(1):227–240

Rosenzweig MR, Wolpin KI (1987) Testing the quantity-quality fertility model: the use of twins as a natural experiment. Econometrica 36:163–184

Rosenzweig MR, Zhang J (2009) Do population control policies induce more human capital investment? Twins, birth weight and China’s ‘One-Child’ Policy. Rev Econ Stud 76:1149–1174

Schultz TP (1985) Changing world prices, women’s wages, and the fertility transition: Sweden, 1860–1910. J Polit Econ 93(6):992–1015

Shiue C (2017) Human capital and fertility in Chinese clans before modern growth. J Econ Growth 22(4):351–396

StephensJr M, Yang D-Y (2014) Compulsory education and the benefits of schooling. Am Econ Rev 104:1777–1792

Willis RJ (1973) A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. J Polit Econ 81(2):S14–S64

Acknowledgements

We thank editor Oded Galor and three anonymous referees, as well as David Blau, Isaac Ehrlich, Daeho Kim, Randy Olson, Mel Stephens, Arthur Sweetman, Casey Warman, and seminar participants at McMaster University, SUNY-Buffalo, The Ohio State University, Dalhousie University, Waterloo University, and the NBER. We are especially indebted to Phil Oreopoulos for his helpful comments and for sharing useful data with us. Both authors recognize funding from SSHRC while this paper was being completed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Oded Galor

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeCicca, P., Krashinsky, H. The effect of education on overall fertility. J Popul Econ 36, 471–503 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-022-00897-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-022-00897-y