Abstract

Naturalization bestows economic benefits to immigrants, their families, and communities through greater access to employment opportunities, higher earnings, and homeownership. It is the cornerstone of immigrant assimilation in the United States. Yet, less than 720,000 of the estimated 8.5 million legal permanent residents (LPRs) eligible to naturalize do so on a yearly basis. Using data from the 2008–2018 American Community Survey, we analyze how the expansion of interior immigration enforcement impacts the decision to naturalize. We find that the adoption over an entire year of one enforcement initiative, or of two enforcement initiatives for half a year, raises the naturalization hazard by 2 percent. The effect is more pronounced among LPRs who are Mexican, women, or reside in non-mixed status households. Finally, the impact is driven by police-based, as opposed to employment-based, interior immigration enforcement. In sum, immigrants who naturalize in response to intensified enforcement may be doing so out of fear or uncertainty about their ability to secure their citizenship status and rights in a rapidly changing immigration policy environment increasingly hostile towards immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Naturalization is defined as the acquisition of US citizenship by a foreign citizen or national after fulfilling the requirements established by Congress in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).

See the CCIS Interactive Map on the Eligible-to-naturalize Population in the U.S. at https://dornsife.usc.edu/csii/eligible-to-naturalize-map/.

See data from The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at http://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/removehistory/.

See also Van Hook et al. (2006), who show that naturalization increased because of PRWORA and positive social contexts of immigrant reception.

See also Claudia Torrens and Gisela Salomon, “Fear of deportation drives people off food stamps in US” AP News, June 6, 2017; https://www.apnews.com/3c0b89362c414003a2603deaab43a702. Last accessed on January 21, 2020.

For more information, see Miriam Jordan, “Citizenship Applications in the US Surge as Immigration Talk Toughens” New York Times, October 27, 2017; Caitlin Yoshiko Kandil, “Fearing Deportation, Asian Immigrants in America Obtain US Citizenship” Los Angeles Times, December 21, 2017; and Kate Linthicum, “More People Are Filing to Become Citizens in the Face of Anti-Immigration Policies” Los Angeles Times, April 22, 2016.

Green card holders are still subject to deportation under criminal offenses. See Alejandra Molina, “Legal Residents Seek Citizenship When Green Cards Are Not Enough” Press-Enterprise, February 11, 2017.

For example, see Kirk Semple, “Making Choice to Halt at Door of Citizenship,” New York Times, August 25, 2013.

IPUMS-USA, University of Minnesota, https://usa.ipums.org/usa/.

The ACS, while highly representative of the immigrant population during this recent period of intensified enforcement, lacks information on the LPR status of the foreign-born.

For more information on the construction of the estimates, see Manuel Pastor and Justin Scoggins, “Estimating the Eligible-to-Naturalize Population” memo, USC Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, March 8, 2016.

ICE (2012a, 2012b, 2012c).

The ACS provides limited county information. The most comprehensive level of geographic detail ends up being the MSA level.

These two additional indices strengthen our enforcement index by providing greater geographic variation in immigration enforcement.

For example, if an MSA is comprised of two counties, the Enforcement Index for SComm (or MSA-287(g)) assigned to MSA m in year t would be given by: \(\begin{array}{l}EI_{m,t}^{SComm} = \frac{{Months\_coverage}}{{12}} \ast \frac{{Cnty1\_Pop}}{{MSA\_Pop}} + \\ \frac{{Months\_coverage}}{{12}} \ast \frac{{Cnty2\_Pop}}{{MSA\_Pop}}\end{array}\)

Thus the \(Total\,Enforcement\,Index_{m,t} = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{k = 1}^5 {EI_{m,t}^k}\) where k = SComm, MSA-287g, State-287g, OIL, and E-verify.

It is worth noting that the index is a proxy of the intensity of immigration enforcement to which respondents in a particular MSA might be exposed. The true intensity of any enforcement measure will inevitably vary across jurisdictions as each one is different and might implement like measures more or less strictly depending on who is in charge of its implementation or other unobserved local traits. To address that limitation, we include area fixed effects as well as area-specific time trends intended to capture such idiosyncrasies.

In the analysis of the sources of impacts, our five individual indices are separated into police and employment-based measures. For \(police - based\,enforcemnt_{m,\,t} = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{k = 1}^4 {EI_{m,t}^k}\) where k = SC, MSA-287g, State-287g, and OIL. It is the sum of the four measures for each MSA and year. The \(employment - based\,enforcement_{m,t} = E - verify_{m,t}\).

Immigration enforcement is an interconnected system administered by various federal, state, and local authorities and agencies with similar missions. Some measures, such as Secure Communities, were enacted to replace prior measures, like the 287(g) program.

The allocation of federal funds for processing naturalization cases is more likely to be based on the number of migrants residing in the jurisdiction of the respective offices than on the level of interior immigration enforcement. However, to rule out the possibility that cities with longer wait times may also have higher levels of enforcement, we examined the enforcement levels for the top ten cities with the longest wait times. Cities with the longest wait times were not among the cities with the highest levels of enforcement.

We also included an indicator for whether it was a presidential election year given the launched naturalization campaigns in some occasions. However, it drops due to collinearity once we include year fixed effects.

We estimate our models using ordinary least squares to facilitate convergence when working with large samples and model specifications with numerous fixed effects (Wooldridge 2012).

Throughout the paper, we report our estimates as follows: [βlaggedEI/D.V. Mean]*100. In this case, the effect is given by: [0.001/0.046]*100 = 2.17 percent.

We also conduct the analysis: (1) using the enforcement level for the same year respondents report having naturalized for those instances in which processing occurs quickly, and (2) including those who moved within the past year. In both instances, the results prove robust. If anything, the magnitude of the impact is somewhat larger. In the case of using the level of interior immigration enforcement of the naturalization year, adopting one more enforcement initiative raises the naturalization propensity by 6.5 percent, versus 2.2 percent. If we include movers within the past year, the same increase in enforcement raises the naturalization likelihood by 10.9 percent. Results are available from the authors.

We calculate 54 percent as 0.025/0.046 where 0.046 is the dependent variable mean.

Section C in the Appendix contains a detailed explanation of the alternative methodology used to identify and exclude likely undocumented immigrants, as well as the results obtained using the alternative sample that results from that exercise. Specifically, the adoption of one interior immigration enforcement initiative raises naturalization hazard of LPRs by approximately 8.16 percent (0.004/0.049). Similarly, eligible-to-naturalize individuals in mixed-status households are 59 percent less likely to naturalize than their counterparts in other households.

The ACS only reports current employment status so we are unable to gauge how E-Verify might have interfered with the assimilation of some migrants by restricting their employment and earnings opportunities in the past.

We also explore the role played by sanctuary policies in migrants’ naturalization decision. Specifically, we focus on state-level Trust Acts whereby sates limited their cooperation with federal immigration authorities (e.g., California Trust Act). Although only a few states have adopted such policies, we find that eligible-to-naturalize migrants in sanctuary states are less in a rush to naturalize in response to intensified immigration enforcement than their counterparts in non-sanctuary states.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Budget in Brief, fiscal years 2003-2013 (http://www.dhs.gov/dhs-budget).

Data on apprehensions can be found in Table 33 at:

http://www.dhs.gov/yearbook-immigration-statistics-2013-enforcement-actions,

and data on interior removals can be found at:

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, E-Verify Overview, 2015.

In 2013, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) decided not to any new agreements.

A portion of Secure Communities was temporarily suspended by DHS from November 20, 2014 through January 25, 2017. The program was reactivated from January 25, 2017 through the end of the 2017 fiscal year. See http://www.ice.gov/secure-communities.

National Conference of State Legislators, http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/2013-immigration-report.aspx.

Not all characteristics used by Borjas (2017) from the CPS data can be found in the ACS. For example, Borjas (2017) also includes a condition for residing in public housing or receiving rental subsidies. This information is not available in the ACS. Similarly, it is unclear which occupations required a license in the definition employed in the study. As a result, while we closely mirror Borjas’ (2017) technique, our proxy is not an exact replica of his. Yet, our results across several years also match DHS estimates.

References

Aguilasocho, E., Rodwin, D. and Ashar, S. (2012). Misplaced priorities: the failure of Secure Communities in Los Angeles County. UC Irvine School of Law Research Paper No. 2013-118.

Alsan, M. and Yang, C. (2019). Fear and the safety net: evidence from Secure Communities. NBER Working Paper 24731.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Bansak, C. (2012). The labor market impact of mandated employment verification systems. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 103, 543–8.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Bansak, C. (2014). Employment verification mandates and the labor market outcomes of likely unauthorized and native workers. Contemporary Economic Policy, 32, 671–80.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Lopez, M. (2017). Interior immigration enforcement and the political participation of us citizens in mixed-status households. Demography, 54(6), 2223–47.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Pozo, S. (2019). The aftermath of tougher immigration enforcement: e-verify and perceptions of discrimination among hispanic citizens. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(63), 1299–1330.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Pozo, S. (2014). On the intended and unintended consequences of enhanced border and interior immigration enforcement: evidence from deportees. Demography, 51(6), 2255–79.

Becerra, D., Alex Wagaman, M., Androff, D., Messing, J., & Castillo, J. (2017). Policing immigrants: fear of deportations and perceptions of law enforcement and criminal justice. Journal of Social Work, 17(6), 715–31.

Bloemraad, I. (2002). The North American naturalization gap: an institutional approach to citizenship acquisition in the United States and Canada. International Migration Review, 36(1), 193–228.

Bohn, S., and Lofstrom, M. (2012). Employment effects of state legislation against the hiring of unauthorized immigrant workers. IZA Discussion Paper Series, no. 6598.

Bohn, S., Lofstrom, M., & Raphael, S. (2014). Did the 2007 Legal Arizona Workers Act reduce the state’s unauthorized immigrant population? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(2), 258–269.

Borjas, G. (2017). The labor supply of undocumented immigrants. Labour Economics, 46, 1–13.

Bratsberg, B., Ragan, Jr, J. F., & Nasir, Z. M. (2002). The effect of naturalization on wage growth: a panel study of young male immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(3), 568–97.

Chiswick, B, and Miller, P. (2008). Citizenship in the United States: the roles of immigrant characteristics and country of origin. IZA Discussion Paper Series, no. 3596.

Enchautegui, M. E., and Giannarelli, L. (2015). The economic impact of naturalization on immigrants and cities. Urban Institute Research Report, New York, NY.

Hainmueller, J., Lawrence D., Gest, J., Hotard, M., Koslowski, R. and Laitin D.D. (2018). A randomized controlled design reveals barriers to citizenship for low-income immigrants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (5): 939–944.

Jones-Correa, M. (2001). Institutional and contextual factors in immigrant naturalization and voting. Citizenship Studies, 5(1), 41–56.

Kandil, C. Y. (2017). Fearing deportation, Asian immigrants in America obtain US citizenship. Los Angeles Times. 21 Dec 2017.

Kostandini, G., Mykerezi, E., & Escalante, C. (2014). The impact of immigration enforcement on the U.S. farming sector. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 96(1), 172–192.

Mathema, S. (2017). Keeping families together: why all americans should care about what happens to unauthorized immigrants. Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, University of Southern California, https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/731/docs/KeepFamiliesTogether-brief.pdf.

Mazzolari, F. (2009). Dual citizenship rights: do they make more and richer citizens? Demography, 46(1), 169–91.

Nguyen, M. T., & Gill, H. (2015). Interior immigration enforcement: the impacts of expanding local law enforcement authority. Urban Studies, 52(2), 302–323.

Orrenius, P., and Zavodny, M. (2017). Unauthorized Mexican workers in the United States: recent inflows and possible future scenarios. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Research Department, Working Paper 1701.

Passel, J. S. (2007). Growing share of immigrants choosing naturalization. Pew Research Center. Hispanic Trends. 28 Mar 2007. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2007/03/28/growing-share-of-immigrants-choosing-naturalization/.

Passel, J. S., and Cohn, D’V. (2014). Unauthorized immigrant totals rise in 7 states, fall in 14: decline in those from Mexico fuels most state decreases. Pew Research Center. Hispanic Trends. 18 Nov 2014. https://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/11/18/unauthorized-immigrant-totals-rise-in-7-states-fall-in-14/.

Pastor, M. and Scoggins, J. (2012). Citizen gain: the economic benefits of naturalization for immigrants and the economy. Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, University of Southern California, https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/731/docs/citizen_gain_web.pdf.

Pierce, S., & Selee, A. (2017). Immigration under Trump: a review of policy shifts in the year since the election. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Preston, J. (2011). Immigration crackdown also snares Americans. New York Times, 14 Dec 2011, A20.

Rendall, M. S., Ghosh-Dastidar, B., Weden, M. M., Baker, E. H., & Nazarov, Z. (2013). Multiple imputation for combined-survey estimation with incomplete regressors in one but not both surveys. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(4), 483–530.

Ruggles, S, Genadek, K, Goeken, R, Grover, J., & Sobek., M. (2017). Integrated public use microdata series: version 7.0 [CPS]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V7.0.

Shierholz, H. (2010). The effects of citizenship on family income and poverty. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper No. 256.

Singer, A., & Gilbertson, G. (2000). Naturalization under changing conditions of membership: Dominican Immigrants in New York City. In Nancy Foner, Ruben Rumbaut & Steven Gold eds, Immigration research for a new century: multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 157–186). New York, NY: Russell Sage Press.

Taylor, P., Gonzalez-Barrera, A., Passel, J. S., & Lopez, M. H. (2012). An awakened giant: the hispanic electorate is likely to double by 2030. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). (2017). Naturalization fact sheet. uscis.gov. 19 May 2017. https://www.uscis.gov/news/fact-sheets/naturalization-fact-sheet.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). (2019). Budget-in-brief, FY 2003–2016. DHS Budget. Updated 18 Mar 2019. http://www.dhs.gov/dhs-budget.

Van Hook, J., Bachmeier, J. D., Coffman, D. L., & Harel, O. (2015). Can we spin straw into gold? An evaluation of immigrant legal status imputation approaches. Demography, 52(1), 329–54.

Van Hook, J., Brown, S. K., & Bean, F. D. (2006). For love or money? Welfare reform and immigrant naturalization. Social Forces, 85(2), 643–66.

Watson, T. (2013). Enforcement and immigrant location choice. NBER Working Paper No. 19626. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Watson, T. (2014). Inside the refrigerator: immigration enforcement and chilling effects in medicaid participation. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(3), 313–38.

Wong, T. K. (2012). 287(g) and the politics of interior immigration control in the United States: explaining local cooperation with federal immigration authorities. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(5), 737–56.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2012). Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Zong, J. and Batalova, J. (2016). Naturalization trends in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 10 Oct 2016. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/naturalization-trends-united-states.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix A: The intensity of interior immigration enforcement

The past two decades have witnessed an impressive expansion of interior immigration enforcement. Between 2003 and 2013, funding for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency—the federal agency responsible for interior immigration enforcement—increased approximately 80 percent, apprehensions more than doubled, and removals increased by three-fold.Footnote 31 The increase in the intensity of interior immigration enforcement has been made evident by the greater participation of local and state governments in a number of immigration enforcement initiatives and programs. For instance, E-Verify is a free internet-based system provided by the United States government that allows employers to determine the employment eligibility of new hires. As of January 2015, the number of participating employers had risen above 550,000 and 19 states had enacted legislation requiring some level of mandatory E-Verify use (either among all employers, or by public sector employers and contractors).Footnote 32 Bohn and Lofstrom (2012) and Bohn et al. (2014) document that the 2007 Legal Arizona Workers Acts (LAWA) –which mandated, for the first time, all Arizona employers to use E-Verify—reduced the employment of likely unauthorized immigrants. Looking across all states, Amuedo-Dorantes and Bansak (2012, 2014) find that the state adoption of mandatory E-Verify laws results in unauthorized migrants relocating to states without mandatory legislation or being forced to accept employment in the underground economy. In the process of evading state mandates or employers who have adopted E-Verify, greater emotional and financial stress is likely to be placed on unauthorized immigrants and their families.

In addition to E-verify, programs such as 287(g) and Secure Communities strengthened the partnership between federal immigration authorities and state and local police, further intensifying interior immigration enforcement. The U.S. government’s 287(g) program allowed state and local law enforcement to establish a partnership with the federal government under joint Memorandum of Agreements, in which state and local law enforcement would receive federal authority for immigration enforcement within their jurisdictions. In 2006, only five counties collaborated with the federal government. By 2008, that number had jumped to 41 counties (Wong 2012). Between 2006 and 2010, the budget for 287(g) increased from $5 million to $68 million, with over 1500 state and local law enforcement officers trained and granted authorization to enforce federal immigration laws (Nyugen and Gill 2015). In response to the rolling out of the program, immigrants altered their residential choices. Watson (2013) finds that immigrants responded to local 287(g) agreements by relocating within the United States, but that this internal migration effect was concentrated among educated non-citizens.

In 2008, as ICE debated whether to continue renewing 287(g) agreements, Secure Communities was introduced.Footnote 33 Secure Communities is an information-sharing program used in the apprehension and deportation of unauthorized immigrants. Under the program, local law enforcement agencies can submit information from arrests, such as fingerprints, to an integrated database with ICE that allows for the identification of the immigration status and criminal activity of any individual. In the latter case, ICE requests that local authorities hold certain individuals for deportation. By 2013, every jurisdiction in the United States was covered under Secure Communities, compared to just 14 jurisdictions in 2008.Footnote 34 Both programs, the latter one replaced by the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP) in 2015, have been criticized for aiding in the deportation of immigrants with no criminal records, creating a strong fear of law enforcement officials among immigrants, and pushing unauthorized migrants and their families into the shadows (Nguyen and Gill 2015; Aguilasocho et al. 2012; Preston 2011).Footnote 35

Finally, a number of state-level omnibus immigration laws further contributed to the intensification of interior immigration enforcement. According to the National Conference of State Legislators, five states adopted laws similar to Arizona’s SB 1070 in 2011 (i.e., Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, and Utah). One year later, five additional states introduced immigration enforcement legislation (i.e., Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Rhode Island, and West Virginia).Footnote 36 Despite the recent drop in proposed state-level immigration enforcement legislation, the increase in omnibus immigration laws after 2010 received considerable national attention and identified the states that wanted to take immigration enforcement into their own hands, thereby fostering an atmosphere of fear and anxiety resulting from increased family separations and migrant abuse reports. In that regard, Amuedo-Dorantes and Pozo (2014) document how apprehension in a state with an omnibus immigration law is more likely to lead to family separation, as well as how the incidence of physical and verbal abuse towards unauthorized migrants increases with the number of states enacting such laws.

1.2 Appendix B: Immigration policy descriptions

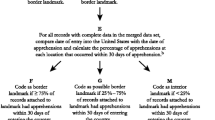

Table 8

1.3 Appendix C. An alternative definition of the likely unauthorized

It is important to ensure that our results are not being driven by our definition of the likely unauthorized population, which is used to identify likely unauthorized immigrants who are then excluded from our sample in order to focus only on eligible-to-naturalize migrants. Given the sample period we are focusing on, plus the fact that his estimates closely mirror those from the Department of Homeland Security for the undocumented population, we follow a modified version of Borjas’ (2017) latest method for imputing undocumented status. Specifically, we classify individuals as unauthorized migrants if all of the following conditions apply:Footnote 37

-

a.

The person is a non-citizen;

-

b.

The person was not born in Cuba;

-

c.

The person arrived after 1980;

-

d.

The person did not receive Social Security benefits, SSI, Medicaid, or Medicare insurance;

-

e.

The person did not receive welfare assistance;

-

f.

The person is not employed in the government sector;

-

g.

The person is not a veteran or is currently in the Armed Forces;

-

h.

The person’s occupation does not require some form of licensing (such as physicians, registered nurses, air traffic controllers, lawyers, etc.); and

-

i.

The person’s spouse is not a naturalized citizen.

Once we categorize the potentially unauthorized immigrant population, we exclude those individuals from our sample and re-estimate Eq. (1) using our new sample. Results from this exercise are shown in Table 9. The estimates are similar to our results in Table 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Lopez, M. Recent changes in immigration policy and U.S. naturalization patterns. Rev Econ Household 19, 843–872 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09510-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09510-1