Abstract

This paper is a sequel to Aschakulporn and Zhang (J Futures Mark 42(3):365–388, 2022). The errors of the Bakshi et al. (Rev Financ Stud 16(1):101–143, 2003) risk-neutral moment estimators is studied using the Gram–Charlier density—with the skewness and excess kurtosis specified. To obtain skewness with (absolute) errors less than \(10^{-3}\), the range of strikes (\(K_{\min }, K_{\max }\)) must contain at least 3/4 to 4/3 of the forward price and have a step size (\(\Delta K\)) of no more than 0.1% of the forward price. The range of strikes and step size corresponds to truncation and discretization errors, respectively. This is consistent to Aschakulporn and Zhang (2022) for non-volatile market periods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper examines the Bakshi et al. (2003) (BKM) risk-neutral estimators with explicit skewness and kurtosis as both the input and benchmark and finds the condition of strike prices required to bound the errors of skewness. The BKM estimators have been widely used in the literature and are used by both academics and practitioners; for example, the BKM estimator for skewness is used to calculate the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) skewness (SKEW) index,Footnote 1 the forward-looking tail-risk or crash risk indicator of the S&P 500 index. Although the errors of the BKM estimators have been studied by Aschakulporn and Zhang (2022) (AZ), the relationship between the model’s parameters and skewness is complicated. This paper analyzes the BKM risk-neutral estimators using simulated option prices generated by a closed-form option-pricing formula with skewness and kurtosis (derived using the Gram–Charlier density)—in doing so, the estimated values can be compared directly with their true values.

A literature review regarding the use and importance of the BKM estimators is presented in AZ. Four papers have examined BKM errors—AZ, Ammann and Feser (2019), Liu and van der Heijden (2016), and Lee and Yang (2015)—with AZ being the key piece of the literature. Prior to AZ, the most advanced model used was the Bates (1996) model—a combination of Heston’s (1993) stochastic volatility and Merton’s (1976) jump. AZ use the Duffie et al. (2000) double-jump affine jump-diffusion model and derive the skewness analytically to get the closed-form solution; this removes the approximation aspect of previous literature. However, due to the complexity of the affine jump-diffusion model, the entire range of their parameters cannot be examined exhaustively, and the relationship between skewness and the model parameters is also lengthy.

Following AZ, the errors of BKM risk-neutral moment estimators caused by truncation and discretization are tested using simulated option prices. The BKM estimators are derived in a setting that has options with a continuum of strikes over an infinite domain; this, however, does not match reality, as options data have discrete strikes over a finite domain. These discrete strikes cause discretization errors, and a finite domain causes truncation errors. Having complete control over options allows the errors of the BKM estimators to be analyzed without external influences in a controlled manner. Using simulated option prices, the BKM estimators can be applied and the estimates can be compared with the true moments calculated from the model originally used to create the options. Similar to AZ, the true moments need not be found from simulations or approximated. The true moments are instead found analytically. For AZ, their formula is quite lengthy; whereas for the Gram–Charlier density, the true moments are specified, not obtained, as the input parameters are the moments themselves. Following Zhang and Xiang (2008), option prices are generated using an option pricing formula with skewness and excess kurtosis (hereinafter, kurtosis). The Gram–Charlier density is used as it provides a way to introduce higher-order moments, namely skewness and kurtosis, to the standard normal distribution. This method has been used by many, including Jarrow and Rudd (1982), Corrado and Su (1996), Longstaff (1995), Backus et al. (1997), Kochard (1999), and Corrado (2007). Using AZ’s framework, the effects of constant and linear extrapolation, and linear, cubic spline, and kernel interpolation on the BKM estimators are similarly tested. In addition, this paper extends the analysis of AZ to examine the volatility, cubic, and quartic contracts used to calculate the BKM estimators in depth. The error of the approximate convexity term used to derive the BKM estimators is also examined.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents an option pricing model with skewness and kurtosis. Section 3 presents the method used to create options prices and the method used to quantify and analyze the errors and convergence of the BKM method. Section 4 describes the data. Section 5 provides the numerical results, and Sect. 6 concludes. The appendix gives the details of key derivations, including part A which briefly presents the BKM risk-neutral moment estimators.

2 Option pricing formula with skewness and kurtosis

The return of the Black-Scholes model is normally distributed. The return has no skewness or excess kurtosis. The Gram–Charlier series is a statistical method that is commonly used to introduce skewness and kurtosis (and higher-order moments) to the normal distribution.Footnote 2 Combining the two, a parsimonious option-pricing formula with skewness and kurtosis can be derived. The two additional parameters, the skewness and kurtosis, are the parameters of interest for this paper. As there are only two additional parameters, examining their effects on errors comprehensively is possible.

2.1 Option pricing using the Gram–Charlier density

This paper follows Zhang and Xiang (2008) to derive the option-pricing formula. They first specify the underlying stock price at maturity, \(S_T\), to be

where \(F_{t}^{T}\), \(\sigma \), \(\tau \), \(\mu _{c}\), and \(y\) is the forward price, standard deviation, time to maturity (\(T - t\)), convexity adjustment term, and a random variable, respectively. Using the Gram–Charlier density, if y has probability density

where \(n\left( y \right) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi }} e^{-\frac{y^2}{2}}\), then \(y\) will have a mean of zero, variance of one, skewness equal to \(\lambda _1\) and an excess kurtosis of \(\lambda _2\). The forward price, \(F_{t}^{T}\), is related to the current stock price, \(S_{t}\), by \(F_{t}^{T} = S_{t} e^{\left( r - q \right) \tau }\), where \(r\) is the risk-free rate and \(q\) is the continuous dividend rate. The convexity adjustment term is required to keep this model arbitrage-free by ensuring that the stock price satisfies the martingale condition (\(F_{t}^{T} = E_{t}^{\mathcal{Q}}\left[ S_{T} \right] \)) in the risk-neutral world and was found to be

Using the risk-neutral valuation formula of Harrison and Kreps (1979) and Harrison and Pliska (1981), Proposition 1, the European call option pricing formula with skewness and kurtosis can be derived.

Proposition 1

The price of a European call option with skewness and kurtosis is

where

The European put option price can be found using the put-call parity:

Remark 1

If the skewness, \(\lambda _1\), and excess kurtosis, \(\lambda _2\), are both zero, then the convexity adjustment term \(\mu _{c}\) will also be zero and Eq. (4) will be equivalent to Black and Scholes (1973).

Remark 2

There is a minor error in Zhang and Xiang (2008), which, once fixed, allows the final result to be expressed more concisely. In Appendix B of Zhang and Xiang (2008), the proof of proposition 2, the call price is given as:

where

and \(d_1\) and \(d_2\) are the same as Eq. (4). The first term \(F_0 e^{-r \tau }\) should be \(F_0 e^{\left( \mu _{c} - r \right) \tau }\). With the additional \(\mu _{c}\) term, the formula can be simplified to Eq. (4).

Remark 3

The results of Kochard (1999) and Schlögl (2013) are equivalent to Eq. (4), however, due to their choice of arrangement, their final expression was not simplified further. Kochard (1999) incorrectly defines \(d_2\) as \(\frac{\mu _{\tau } - \ln \left( \frac{X}{S_0} \right) }{\sigma _{\tau }}\), missing the dividend term, in Appendix 2.1. Correcting this gives \(d_2 = \frac{\mu _{\tau } - \delta \tau - \ln \left( \frac{X}{S_0} \right) }{\sigma _{\tau }}\). Ki et al. (2005) also derive an equivalent expression but did not simplify the expression.

Remark 4

Backus et al. (1997) derive a similar formula; however, their martingale restriction is an approximation of the convexity adjustment term (Eq. (3)). In the proof of proposition 1 in the appendix, they incorrectly define their \(I_3\) with the third derivative instead of the fourth. Correcting this gives, \(I_3 = \int _{w^{*}}^{\infty }{\left( S_t e^{\mu _{n} + \sigma _{n} w} - K \right) \varphi ''''\left( w \right) dw}\).

Remark 5

Corrado (2007) makes the risk-neutral stock price model a martingale in the risk-neutral measure by adding

to Eq. (2). Equation (4) can be transformed to Corrado (2007) by setting \(\mu _c = 0\) in \(d_2\).

Remark 6

The option pricing formula (Eq. (4)) can be transformed into the Brown and Robinson (2002) correction of Corrado and Su (1996) by replacing \(F_t^{T}\) with \(S_t e^{\left( r - q - \mu _{c} \right) \tau }\). Corrado and Su (1996) does not have a martingale restriction to ensure that the model satisfies the no-arbitrage principle.

Remark 7

Heston and Rossi (2017) correctly apply the Gram–Charlier density in a general form which encompasses both Corrado and Su (1996) and Eq. (4), by setting their \(\mu \) to \(\ln S_0 + r - q - \frac{1}{2}\sigma ^2\) and \(\ln S_0 + r - q + \mu _{c} - \frac{1}{2}\sigma ^2\), respectively—using their notation. They also extend from using Hermite polynomials to logistic polynomials (another orthogonal polynomial) and show that orthogonal polynomials can be used to span option payoffs. However, Hermite polynomials tend to diverge unlike logistic polynomials.

Remark 8

An advantage of using the Gram–Charlier density is that it can be easily extended to have an arbitrary number of additional moments/cumulants while satisfying the martingale condition.

For the purposes of this paper, the Gram–Charlier density (Eq. (2)), including only the skewness and kurtosis term is used. Figure 1 shows the region of skewness and kurtosis, which ensures a valid density function. The derivation of this region and an alternate formulation of the density is shown in the appendix, part D.

Gram–Charlier valid region. This figure shows the region (shaded area) in which pairs of skewness and kurtosis values will yield a valid probability density function using the Gram–Charlier density. The curve represents the skewness and kurtosis required to make the density function vanish. Point A corresponds to the origin and points B to O correspond to various values of \(x\) between \(-\infty\) and \(\infty \)

This formulation (Eq. 4) is ideal for testing the BKM estimators. The stock price model satisfies the no-arbitrage principle, unlike Corrado and Su (1996). The martingale restriction is not approximated like Backus et al. (1997). The expression is clearer and more elegant compared to Kochard (1999), Schlögl (2013), and Ki et al. (2005). The relationship between the model’s skewness and excess kurtosis and inputs are clear as they are the same, unlike Corrado (2007) and Chateau and Dufresne (2017).

3 Methodology

To analyze the errors of BKM risk-neutral moment estimators, a controlled environment with clear benchmarks and parameters would be ideal. Part A of the appendix presents a brief derivation of the BKM estimator. The BKM estimator requires the use of option prices which can be provided by simulated option prices generated based on the Gram–Charlier density. The Gram–Charlier density is ideal, as it provides a malleable framework with skewness and kurtosis that are explicitly specified as parameters. These parameters are used as direct benchmarks against the moments calculated by the BKM estimator.

The procedure to test the BKM estimator is to (1) generate simulated option prices (Sect. 3.1), (2) apply the BKM estimator (Part A of the appendix), and (3) compare the estimates with their true values (Sect. 3.2). In addition to this, various interpolation and extrapolation techniques could be tested by introducing these techniques before applying the BKM estimator. This procedure follows the error analysis of AZ with the addition of a more comprehensive and in-depth analysis. Instead of testing two data points in two different market periods, the entire range of parameters (2515 points) is tested using the Gram–Charlier approach. Each contract used to calculate the BKM estimators are examined individually and with a smaller step size in Sect. 5.4. The rare disaster concern index (RIX) from Gao et al. (2018) and simple variance swaps (SVIX) from Martin (2016) are also tested.

3.1 Simulated option prices using the Gram–Charlier density

The options prices generated by Eq. (4) will be for an underlying asset with a specified return distribution. These values can be generated with specific sets of strike prices to test various errors. As the skewness and kurtosis is bounded by the valid region of the Gram–Charlier density (shown in Fig. 1), 2515 different pairs of skewness and kurtosis values within the valid region were chosen for analysis. These points are shown in Fig. 2.

Using the Gram–Charlier approach, the BKM estimator errors can be found directly. Similarly, other estimators can be tested with this approach. The CBOE VIX, rare disaster concern index, RIX, from Gao et al. (2018) and simple variance swaps, SVIX, from Martin (2016) derived under the Gram–Charlier model is shown in the appendix, part E.

3.2 Errors from truncation and discretization

Following AZ, the truncation and discretization errors are the two sources of errors that were tested. The same definitions are used to allow for consistency. These are presented in part B of the appendix for convenience. For calculations, the maximum and minimum strike prices are rounded to the nearest dollar and the boundary controlling factor, a, is varied between 0.05 and 0.95 in 0.01 intervals.Footnote 3 The step size, \(\Delta K\), has been chosen to vary from 1 to 50, in increments of 1.Footnote 4

For each combination of a and \(\Delta K\), of which there are 4550 (91 × 50), the mesh of points (pairs of skewness and kurtosis) within the valid Gram–Charlier region have been used to generate simulated option prices (as described in Sect. 3.1). From this, the discretized BKM method is applied to each set of options to find the risk-neutral moments. The estimation error is defined as

following AZ.

The error for each point in the valid Gram–Charlier region for a specific combination of a and \(\Delta K\) is averaged to find the average error for the whole valid region. The maximum of the absolute value of the error over the valid region was also recorded.

The specification of each parameter is shown in Table 1, and the skewness-kurtosis points used in the valid Gram–Charlier region are shown in Fig. 2.

An example of the error calculation for skewness and kurtosis done for the points from Fig. 2 are shown in Fig. 3. From this, both the average of the errors and the maximum absolute error for each region are plotted at their respective boundary controlling factor and step size.

Example of the errors for skewness and kurtosis. These figures show the errors between the estimated skewness (a) and kurtosis (b) (using the BKM method) and their true values. Based on the valid Gram–Charlier region, of which 2515 pairs of true skewness and kurtosis values were used to calculate the error surface. For this set of figures, \(K \in [500, 8000]\) (\(a = 0.25\)) and \(\Delta K = 1\)

3.3 Errors from the approximated convexity adjustment term

The approximation made by BKM (Eq. A2) can be analyzed analytically by entering the Black and Scholes (1973) stock price model into the approximation,Footnote 5

and comparing the BKM return to the Black-Scholes expected log return \(\left( r - \frac{1}{2} \sigma ^2 \right) \tau \). Clearly, the returns are not the same. This additional term corresponds to the convexity adjustment term \(\mu _c\) as calculated by the BKM method. This is found by comparing the expected log returns of the BKM method and Gram–Charlier density return:

Using Eq. (8) in place of the BKM \(\mu \), the errors caused by BKM’s approximation can be calculated.

3.4 Error reduction by using interpolation and extrapolation

Following AZ, various interpolation and extrapolation techniques are applied to test whether the errors of the BKM estimator can be reduced. Constant and linear extrapolation as well as linear, cubic spline, and Gaussian kernel interpolation were applied to the implied volatility curve. What differs from AZ is that interpolation is done so that the largest step size between each strike is no larger than 0.1% of the forward price (with a minimum of $1), and the extrapolation is done so that the domain contains strike prices between 3/4 and 4/3 of the forward price. In AZ, interpolation was done to 0.05% of the forward price and the boundary controlling factor was 1/4—resulting in smaller step sizes over a larger domain.

4 Data

As this paper uses simulated option prices to test for estimation errors, the data required are minimal and can be set arbitrarily. However, to direct the results towards US markets, specifically the S&P 500, the risk-free rate, volatility, and time to maturity have been set to 2.4%,Footnote 6 0.20, and one month, respectively. These values partially reflect the current market conditions in April 2019. The current market volatility based on the CBOE VIXFootnote 7 is oddly low, so the standard deviation has been chosen to be 0.20. A one month time to maturity has been chosen as these tend to be the most liquid (shortest term contracts).

5 Numerical results

5.1 BKM estimation

The mean errors of the BKM standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis estimators are shown in Table 2. The mean error is the mean of the estimation error (Eq. (6)) calculated over each valid Gram–Charlier region. These errors show that, as expected, the smaller the boundary controlling factor, a, the smaller the approximation error. Similarly, a smaller step size, \(\Delta K\), corresponds to a smaller discretization error. As these two approach zero, the discretization and truncation of the BKM method tend towards an integral over an infinite range. For the average of skewness errors to be less than \(10^{-3}\), the boundary controlling factor and step size, as shown in Table 2, must be less than 0.75 and $20, respectively. A more robust way to limit errors to be below \(10^{-3}\) is done by using the maximum value of the absolute error rather than the mean. This is shown in Table 3. The constraint is stronger and is reflected in the allowable boundary controlling factor and step size. The boundary controlling factor and step size to ensure that the errors are bounded by \(10^{-3}\) must also be bounded by 0.75 and \(\$2\), respectively. The step size is dependent on the forward price; to generalize this result, the step size must be less than 0.1% of the forward price. Comparing the errors of the second to fourth moments shows that the BKM estimator, for these values, is more accurate for lower-order moment estimators. These results are consistent with AZ for a non-volatile market period. During volatile market periods, AZ show that the errors of the BKM skewness estimator are accurate when the boundary controlling factor is 0.25 and the step size is 0.05% of the forward price ($1).

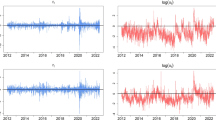

A visual form of Table 2 is presented in Fig. 4. This figure shows that the errors caused by truncation of the integral causes less predictable behaviour, whereas changes in the step size do not seem to affect the error as unpredictably. Although the truncation error is less predictable, when the boundary controlling factor is below 0.75, the behaviour is stable.

Sensitivity of the Average Error for Skewness. Using the Gram–Charlier density, simulated option prices with known standard deviation \(\sigma \), skewness \(\lambda _1\), and kurtosis \(\lambda _2\) were created for a forward price \(F_{t}^{T}\), time to maturity \(\tau \), risk-free rate r, and standard deviation \(\sigma \), have been arbitrarily set to $2000, one month, 2.4%, and 0.20, respectively. In total, 2515 different pairs of skewness and kurtosis (within the Gram–Charlier region) were used. The errors are shown for a varying degree of fineness of strike discretization (\(\Delta K \in [1, 50]\)). The range of strikes used is also varied symmetrically by adjusting \(a \in [0.05, 0.95]\) for \([K_{\min }, K_{\max }] = [F_{t}^{T} \times a, F_{t}^{T}/a]\) (rounded to the nearest dollar). These errors are the averaged errors of the entire valid Gram–Charlier region

Figure 5 shows the projection of Fig. 4 to show just the errors with respect to the step size. Due to the large errors caused by truncation, Fig. 5 shows errors with boundary controlling factor values of 0.05, 0.40, and 0.75. The error boundary of \(10^{-3}\) is shown in red. The same has been done for standard deviation and is shown in Fig. 7. Figures 6 and 8 show the same errors but with respect to the boundary controlling factors for step sizes of 1, 10, and 25.

The skewness errors can easily be restricted below \(10^{-3}\) by fixing \(\Delta K = \$2\) and \(a \le 0.75\). Kurtosis, however, has much larger errors.

The standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis using the BKM method have been calculated for a skewness and kurtosis of \(-1\) and 2.5, respectively. This has been done for a boundary controlling factor value of 0.05, 0.40, and 0.75 and step size of 1 to 50. This is shown in Fig. 9. Figure 10 shows the same errors with respect to the boundary controlling factors.

Values w.r.t. \({\Delta K}\). These figures have been created for boundary controlling factor values of 0.05, 0.40, and 0.75 and for step sizes of \(\Delta K\) from 1 to 50, to 25, and to 10. The true value is shown in red. These figures have been plotted for a standard deviation (\(\sigma \)), skewness (\(\lambda _1\)), and kurtosis (\(\lambda _2\)) of 0.20, \(-1\), and 2.5, respectively (Color figure online)

Values w.r.t. \({a}\). These figures have been created for step sizes of 1, 10, and 25 and for boundary controlling factors of a from 0.05 to 0.95, to 0.75, and to 0.50. The true value is shown in red. These figures have been plotted for a standard deviation (\(\sigma \)), skewness (\(\lambda _1\)), and kurtosis (\(\lambda _2\)) of 0.20, \(-1\), and 2.5, respectively (Color figure online)

To examine the independence of the skewness estimator from kurtosis, the skewness is estimated when the skewness, the boundary controlling factor, and step size are set to \(-1\), 0.25, and 1, respectively, whilst adjusting the kurtosis within the valid Gram–Charlier region. The same has been done for kurtosis when it is set to 2.5. As neither the true skewness nor the true kurtosis has been chosen to be zero, the relative error for each estimator can, therefore, be calculated. The (absolute) relative error is defined as \(\text{ Relative Error } = \left| \frac{x - x_{true}}{x_{true}} \right|\), where x is the estimated value, and \(x_{true}\) is the true value. The maximum(minimum) relative error for skewness and kurtosis were found to be \(4.476 \times 10^{-04}(4.476 \times 10^{-04})\) and \(1.272 \times 10^{-03}(1.245 \times 10^{-03})\), respectively. These relative error curves are monotonically increasing and decreasing, as shown in Fig. 11. These values cannot be used to compare the sensitivity of skewness and kurtosis directly. The difference of the maximum and minimum values for skewness and kurtosis are \(5.866 \times 10^{-08}\) and \(2.663 \times 10^{-05}\), respectively. From this, the effects of kurtosis on the estimation of skewness and vice versa are shown to be insignificant. Therefore, for this case, the estimation of skewness is independent of kurtosis and vice versa.

Independence of Skewness and Kurtosis. These figures show the values and relative errors of skewness when kurtosis is changed (a), and kurtosis when skewness is changed (b). The boundary controlling factor and step size are set to 0.25 and 1, respectively. When testing skewness, the true skewness is set to \(-1\). For kurtosis, the true value is set to 2.5 (Color figure online)

5.2 Convexity adjustment term errors

The errors of using the Black-Scholes return in place of BKM’s approximation have been tabulated in Tables 4 and 5 and presented in Figs. 12 and 13.

Errors w.r.t. \({\Delta K}\) with Alternative Convexity Adjustment Term. These figures have been created for boundary controlling factor values of 0.05, 0.40, and 0.75 and for step sizes of \(\Delta K\) from 1 to 50, to 25, and to 10. The error boundary of \(10^{-3}\) is shown in red (Color figure online)

Tables 4 and 5 have been combined with Tables 2 and 3 in Tables 6 and 7, respectively, to allow for ease of comparison.

In general, there is a slight decrease in both mean and absolute maximum errors for skewness when the boundary controlling factor is less than 0.75. For larger boundary controlling factors, the alternate convexity adjustment term increases the errors.

5.3 Interpolation and extrapolation

The results of interpolation and extrapolation are shown in Tables 8 and 9, respectively.

Table 8 shows that all interpolation techniques reduce the magnitude of skewness error for almost all points. There are a few interpolated points which have errors with greater magnitudes than the non-interpolated case; however, this is due to the oscillating nature of the error. All three interpolation techniques yield much more stable results. Cubic spline performs the best, followed by linear interpolation, then Gaussian kernel regression. The linear interpolation option shows how smoothing the implied volatility curve is more beneficial than interpolating with the option prices directly. As the trapezium rule is used for integration, this effectively is equivalent to linear interpolation of the option prices, which corresponds to the no interpolation or “None” case in Table 8. A reason for this is the shape of the implied volatility curve compared with the option price curve, with respect to the strike price or moneyness. Under the Black-Scholes model, the implied volatility curve is simply a constant line, whereas the price curve is much more complicated. Simply put, linear interpolation of the implied volatility curve is effectively interpolating the price curve non-linearly. Table 8 also shows that if cubic spline interpolation is used, the condition of having a minimum step size no greater than 0.1% of the forward price can be relaxed to 2.5% of the forward price. Table 9 shows that both constant and linear extrapolation, in general, decreases the errors. Constant extrapolation tends to yield more consistent results than linear extrapolation; however, linear extrapolation yields more accurate results. Linear extrapolation, although occasionally more accurate, can lead to negative implied volatilities, depending on the end points of the existing implied volatility curve. Constant extrapolation essentially assumes that the tails of the return are normally distributed, in the same way as Black-Scholes’ model has constant volatility. If the BKM skewness estimator is used directly with no interpolation or extrapolation techniques on S&P 500 index options, based on Eq. (4), the errors are expected to exceed \(10^{-3}\). However, this can be easily remediated by using cubic spline interpolation with linear interpolation. For more stable and reliable results, cubic spline interpolation paired with constant extrapolation may be more appropriate, depending on the breadth of strikes available. These results are also consistent with AZ—although, the conditions are more strict as the affine jump-diffusion model is able to model more volatile markets.

5.4 In-depth error analysis

A closer inspection of errors shows that the current level of granularity of the step size \(\Delta K = 1\) is not sufficient to show the overall form of the relationship between the errors and step size. By reducing the step size to \(\Delta K = 0.001\), this reveals a form which is closer to the true form. This is shown in Fig. 14.

Granularity of step size \({\Delta K}\). The errors for skewness for a boundary controlling factor of \(a = 0.05\) with varying step sizes between 1 and 50 shows that, in general, as the step size gets larger, so do the errors. When the fineness of the granularity is increased from \(\Delta K = 1\) (black line) to \(\Delta K = 0.001\) (red line), the shape of the relationship between the error and the step size is revealed. The forward price \(F_{t}^{T}\), time to maturity \(\tau \), risk-free rate r, standard deviation \(\sigma \), skewness \(\lambda _1\), and kurtosis \(\lambda _2\) are equal to $2000, one month, 2.4%, 0.20, \(-1\), and 2.5, respectively. The error model and envelope (\(E^{\pm }\)) is given by \(\displaystyle \text{ Error } \,\text{ Model } = X \beta ^{s} \sin \left( \frac{2\pi }{X\beta ^{\omega }} \Delta K \right) + X \beta ^{t}\) and \(E^{\pm } = X\left( \beta ^{t} \pm \beta ^{s} \right) \) where \(\beta ^{s} = \begin{bmatrix} 2.311 \times 10^{-04}&1.433 \times 10^{-05} \end{bmatrix}^{T}\), \(\beta ^{t} = \begin{bmatrix} 6.726 \times 10^{-05}&5.366 \times 10^{-06} \end{bmatrix}^{T}\), \(\beta ^{\omega } = \begin{bmatrix} 6.980 \times 10^{-04}&4.967 \times 10^{-04} \end{bmatrix}^{T}\), and \(X = \begin{bmatrix} \Delta K&\left( \Delta K \right) ^2 \end{bmatrix}\)

The error does not decrease exponentially with respect to the step size, but more so quadratically. The error envelope, positive \((+)\) and negative \((-)\), was found using a least-squares approximation of a relatively simple parsimonious quadratic curve:

The coefficients \(\beta _1^{+}\), \(\beta _2^{+}\), \(\beta _1^{-}\), and \(\beta _2^{-}\) were found to be \(2.984 \times 10^{-04}\), \(1.969 \times 10^{-05}\), \(-1.639 \times 10^{-04}\), and \(-8.959 \times 10^{-06}\), respectively. Using these values, the asymmetric envelope can be decomposed into two components, a symmetric envelope and a trend term. The symmetric envelope has parameters \(\beta ^{s}_1\) and \(\beta ^{s}_2\) equal to \(2.311 \times 10^{-04}\) and \(1.433 \times 10^{-05}\), respectively. The trend component has parameters \(\beta ^{t}_1\) and \(\beta ^{t}_2\) equal to \(6.726 \times 10^{-05}\) and \(5.366 \times 10^{-06}\), respectively. The error is oscillating with an increasing period. To capture this behaviour, Eq. (10) seems to be suitable. The increasing period increases approximately quadratically with \(\beta ^{\omega }_1\) and \(\beta ^{\omega }_2\) equal to \(6.980 \times 10^{-04}\) and \(4.967 \times 10^{-04}\), respectively. This model is also presented in Fig. 14. The methodology used to obtain these parameters is presented in the appendix, part G.

As the risk-neutral moments are composed of multiple contracts, which in itself produces errors, the errors of each contract with respect to the step size are shown in Fig. 15.Footnote 8

Contract Errors w.r.t. \({\Delta K}\). The relative errors for the volatility, cubic, and quartic contracts for a boundary controlling factor of \(a = 0.05\) with varying step sizes between 1 and 50 show that, in general, as the step size gets larger, so do the errors. The forward price \(F_{t}^{T}\), time to maturity \(\tau \), risk-free rate r, standard deviation \(\sigma \), skewness \(\lambda _1\), and kurtosis \(\lambda _2\) are equal to $2000, one month, 2.4%, 0.20, \(-1\), and 2.5, respectively. The value of the volatility, cubic, and quartic contracts are \(3.327 \times 10^{-03}\), \(-1.884 \times 10^{-04}\), and \(6.071 \times 10^{-05}\), respectively. The relative error is defined as \(\text{ Relative }\, \text{ Error } := \frac{\text{ Estimated } - \text{ True }}{\text{ True }}\)

The errors of the volatility contract can be modelled the same way as the skewness estimator. The same error model is not appropriate for the other contracts. The coefficients for the volatility contract (relative) errors are \(\beta ^{s} = \begin{bmatrix} 1.487 \times 10^{-04}&8.976 \times 10^{-06} \end{bmatrix}^{T}\), \(\beta ^{t} = \begin{bmatrix} 2.539 \times 10^{-05}&4.631 \times 10^{-06} \end{bmatrix}^{T}\), and \(\beta ^{\omega } = \begin{bmatrix} 2.773 \times 10^{-05}&5.113 \times 10^{-04} \end{bmatrix}^{T}\). The relative error is defined as

6 Conclusion

The importance of the BKM method is clear. It is used by many practitioners and academics as an indicator of tail risk and also to calculate the CBOE SKEW. This paper demonstrates a method to create simulated option prices using the Gram–Charlier density. These simulated prices are created by specifying the mean, variance, skewness, and kurtosis. By doing so, the risk-neutral moment estimators can be compared with the true values. The results show that in order to estimate skewness within \(10^{-3}\) of the true value, the range of strikes (\(K_{\min }, K_{\max }\)) must contain at least 3/4 to 4/3 of the forward price and have a step size (\(\Delta K\)) of no more than 0.1% of the forward price. Rather than using the absolute error as the measure, if the average error is used, then the step size restriction can be relaxed to 1% of the forward price. Under the same boundary controlling factor and step size specification, absolute errors of the kurtosis and standard deviation are bounded by \(5 \times 10^{-3}\) and \(10^{-4}\), respectively.

In general, markets are not able to satisfy the conditions required to calculate skewness with errors less than \(10^{-3}\), hence, interpolation and extrapolation techniques are required. Cubic spline interpolation performs better than linear interpolation and Gaussian kernel regression. For extrapolation, there is a trade-off between stability and accuracy, with constant extrapolation being more stable than the more accurate linear extrapolation. Using both cubic spline and either constant or linear regressions will help reduce discretization and truncation errors of skewness.

AZ provide the prequel to this paper by examining the BKM risk-neutral skewness estimator under the affine jump-diffusion model. The results of this paper are consistent with AZ for market periods that are not too volatile. When volatile periods are included, AZ recommend that linear interpolation to 0.05% of the forward price and constant extrapolation to include strikes at least a quarter to quadruple the forward price (\(a = 1/4\)) should be performed on the implied volatility curve in order to bound the errors of the BKM skewness estimator to be less than \(10^{-3}\). This condition is stricter than the \(a = 3/4\) and \(\Delta K = 0.1\% F_{t}^{T}\) found using the Gram–Charlier approach—this is expected. The Gram–Charlier density introduces skewness and excess kurtosis, whereas the Duffie et al. (2000) model has parameters, such as the instantaneous variance, \(v_{t}\), mean-reverting speed, \(\kappa \), long-term mean, \(\theta \), diffusive volatility, \(\sigma \), correlation between the stock and variance, \(\rho \), jump intensity, \(\lambda \), mean jump size in variance, \(\mu _{y}\), mean jump size in price, \(\mu _{x} + \rho _{J} y\), variance of jump size in price, \(\sigma _{x}^2\), and correlation between jumps, \(\rho _{J}\), which can be combined to get the skewness. With the additional freedom given by the number of additional parameters and the model’s specification, the affine jump-diffusion model can better model the market. However, due to the complexity of the Duffie et al. (2000) model, the errors of the BKM estimators were not analyzed as comprehensively or as in-depth by AZ.

Beyond AZ, this paper finds that the errors of skewness oscillate with respect to the step size. Increasing the granularity of the step size decreases the error approximately quadratically, not exponentially. However, this oscillation can be significantly reduced using interpolation techniques. Also, it was found that errors caused by the approximation (Eq. (A2)) used to derive the BKM estimator is negligible. In addition to the risk-neutral skewness, the risk-neutral standard deviation, risk-neutral kurtosis, VIX, RIX, and SVIX are also examined.

Data availibility

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

The Gram–Charlier density is defined by Jondeau and Rockinger (2001) as the Gram–Charlier series with the positivity constraints imposed.

The boundary controlling factor, a, for S&P 500 options data (from OptionMetrics), based on a symmetric domain about the forward price, ranges from 0.605 to 0.899 and has an average of 0.820 in 2018.

S&P 500 options data from OptionMetics in 2018 show that the minimum step size, \(\Delta K\), is 5 and the maximum, in general, is 100.

The details are shown in the appendix, part F.

Using the Treasury bill rates from https://home.treasury.gov/.

The details of true contract values are shown in the appendix, part H.

Generally, minimum strike price intervals are as follows: (1) $0.50 where the strike price is less than $15, (2) $1 where the strike price is less than $200, and (3) $5 where the strike price is greater than $200. (http://www.cboe.com/products/vix-index-volatility/vix-options-and-futures/vix-options/vix-options-specs)

With the same stock price model:

$$\begin{aligned} S_{T} = F_{t}^{T} e^{\left( -\frac{1}{2} \sigma ^2 + \mu _{c} \right) \tau + \sigma \sqrt{\tau } y}, \end{aligned}$$(1)but with y following the extended Gram–Charlier density (to the mth additional cumulant, \(\kappa _{m}\)). The probability density function is given by

$$\begin{aligned} f(y) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi }} e^{-\frac{1}{2} y^2} \left[ 1 + \sum _{i = 3}^{m}{\frac{\lambda _{i - 2}}{i!} He_{i}(y)} \right] \end{aligned}$$where y now has a mean of 0, variance of 1, skewness of \(\lambda _{1}\), excess kurtosis of \(\lambda _{2}\), and so on (\(\lambda _{i - 2} \approx \kappa _{i}\)).

\(\mu _c\) is found from making \(E_t\left[ S_T \right] = F_t^T\). Which gives \(\mu _c = \mu (\sigma \sqrt{\tau })\) where

$$\begin{aligned} \mu (\sigma ) = -\frac{1}{\tau }\ln \left[ 1 + \sum _{i = 3}^{m}{\frac{\lambda _{i - 2}}{i!} (\sigma )^i} \right] . \end{aligned}$$

References

Ammann, M., & Feser, A. (2019). Robust estimation of risk-neutral moments. Journal of Futures Markets,39(9), 1137–1166.

Aschakulporn, P., & Zhang, J. E. (2022). Bakshi, Kapadia, and Madan (2003) risk-neutral moment estimators: An affine jump-diffusion approach. Journal of Futures Markets, 42(3), 365–388.

Backus, D. K., Foresi, S., & Wu, L. (1997). Accounting for biases in Black-Scholes. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=585623

Bakshi, G., Kapadia, N., & Madan, D. (2003). Stock return characteristics, skew laws, and the differential pricing of individual equity options. Review of Financial Studies, 16(1), 101–143.

Bates, D. S. (1996). Jumps and stochastic volatility: Exchange rate processes implicit in Deutsche Mark options. Review of Financial Studies, 9(1), 69–107.

Black, F., & Scholes, M. (1973). The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 637–654.

Brown, C. A., & Robinson, D. M. (2002). Skewness and kurtosis implied by option prices: A correction. Journal of Financial Research, 25(2), 279–282.

Carr, P., & Madan, D. (2001). Optimal positioning in derivative securities. Quantitative Finance, 1(1), 19–37.

Chateau, J.-P., & Dufresne, D. (2017). Gram–Charlier processes and applications to option pricing. Journal of Probability and Statistics, 2017.

Corrado, C. J. (2007). The hidden martingale restriction in Gram–Charlier option prices. Journal of Futures Markets, 27(6), 517–534.

Corrado, C. J., & Su, T. (1996). Skewness and kurtosis in S&P 500 index returns implied by option prices. Journal of Financial Research, 19(2), 175–192.

Demeterfi, K., Derman, E., Kamal, M., & Zou, J. (1999). A guide to volatility and variance swaps. Journal of Derivatives, 6(4), 9–32.

Duffie, D., Pan, J., & Singleton, K. (2000). Transform analysis and asset pricing for affine jump-diffusions. Econometrica, 68(6), 1343–1376.

Gao, G. P., Gao, P., & Song, Z. (2018). Do hedge funds exploit rare disaster concerns? Review of Financial Studies, 31(7), 2650–2692.

Harrison, J. M., & Kreps, D. M. (1979). Martingales and arbitrage in multiperiod securities markets. Journal of Economic Theory, 20(3), 381–408.

Harrison, J. M., & Pliska, S. R. (1981). Martingales and stochastic integrals in the theory of continuous trading. Stochastic Processes and their Applications, 11(3), 215–260.

Heston, S. L. (1993). A closed-form solution for options with stochastic volatility with applications to bond and currency options. Review of Financial Studies, 6(2), 327–343.

Heston, S. L., & Rossi, A. G. (2017). A spanning series approach to options. Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 7(1), 2–42.

Jarrow, R., & Rudd, A. (1982). Approximate option valuation for arbitrary stochastic processes. Journal of Financial Economics, 10(3), 347–369.

Jondeau, E., & Rockinger, M. (2001). Gram–Charlier densities. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 25(10), 1457–1483.

Ki, H., Choi, B., Chang, K.-H., & Lee, M. (2005). Option pricing under extended normal distribution. Journal of Futures Markets, 25(9), 845–871.

Kochard, L. E. (1999). Option pricing and higher order moments of the risk-neutral probability density function. PhD Thesis. University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Lee, G., & Yang, L. (2015). Impact of truncation on model-free implied moment estimator. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2485513

Liu, Z., & van der Heijden, T. (2016). Model-free risk-neutral moments and proxies. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2641559

Longstaff, F. A. (1995). Option pricing and the martingale restriction. Review of Financial Studies, 8(4), 1091–1124.

Martin, I. (2016). What is the expected return on the market? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(1), 367–433.

Merton, R. C. (1976). Option pricing when underlying stock returns are discontinuous. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(1), 125–144.

Schlögl, E. (2013). Option pricing where the underlying assets follow a Gram/Charlier density of arbitrary order. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 37(3), 611–632.

Zhang, J. E., & Xiang, Y. (2008). The implied volatility smirk. Quantitative Finance, 8(3), 263–284.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Sebastian A. Gehricke, Feng Jiao (our NZFM discussant), Wei Lin, Maximilian Nagl (our ICFOD discussant), Xinfeng Ruan, Fang Zhen, and seminar participants at the University of Otago, 2019 New Zealand Finance Meeting (NZFM 2019) in Auckland, and 9th International Conference on Futures and Other Derivatives (ICFOD 2020) in Zhuhai.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Pakorn Aschakulporn appreciates being awarded the University of Otago Doctoral Scholarship. Jin E. Zhang has been supported by an establishment grant from the University of Otago. The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A BKM risk-neutral moment estimators

This appendix presents the BKM estimator and how it was derived. This is also presented in AZ, but it is included here for readers’ convenience.

The BKM method calculates the risk-neutral (return) skewness (\(n = 3\)) and kurtosis (\(n = 4\)) using the basic normalized nth central moments (viz. standardized moments) equation:

where \(R\left( t, \tau \right) \equiv \ln \left[ S_{T} \right] - \ln \left[ S_{t} \right] \), the log returns. However, BKM makes a small approximation to the mean and sets dividends, q, to zero:

The approximation is due to the exclusion of higher-order terms in the expansion of the exponential function. This approximation serves in a similar manner to the convexity adjustment term in the addition of higher-order moments. For the BKM method, this is in the form of volatility (\(R\left( t, \tau \right) ^2\)), cubic (\(R\left( t, \tau \right) ^3\)), and quadratic (\(R\left( t, \tau \right) ^4\)) payoff contracts. These contracts are not standard; therefore, to calculate their values, the contracts are decomposed into European options, bonds, and shares. Equation 1 in Carr and Madan (2001) shows that any twice-differentiable payoff function with bounded expectation can be spanned by a continuum of out-of-the-money (OTM) European options, bonds, and shares. For payoff function \(H\left( x \right) \in {\mathscr {C}}^2\) and some constant \(x_0\), the decomposed payoff function is given by

Following BKM in using Eq. (A3), setting \(S_{T} = S\), the dependent variable, and setting \(x_0\) to \(S_{t}\), the following payoff

results in \(H\left( S_{t} \right) = 0\), \(H_{x}\left( S_{t} \right) = 0\), and

Finally, the expected value of each contract is given by

where n specifies the type of power contract and \(Q\left( K \right) \) corresponds to the OTM option with strike K. If there exists both put and call at the at-the-money point, then the average of the two is taken. \(n = \{ 2, 3, 4 \}\) corresponds to the volatility (V), cubic (W), and quadratic (X) payoff contracts, respectively. With these payoff contracts, the skewness (and kurtosis) can be calculated using Eq. (A1).

The standardized skewness is given by Eq. (A1) when \(n = 3\). Expanding this, the BKM formula for the risk-neutral skewness can be found. Similarly, the standardized kurtosis can be found when \(n = 4\). BKM defines \(\mu \), V, W, and X as \(E_{t}^{\mathcal{Q}} \left[ R\left( t, \tau \right) \right] \), \(E_{t}^{\mathcal{Q}} \left[ e^{-r\tau } R\left( t, \tau \right) ^{2} \right] \), \(E_{t}^{\mathcal{Q}} \left[ e^{-r\tau } R\left( t, \tau \right) ^{3} \right] \), and \(E_{t}^{\mathcal{Q}} \left[ e^{-r\tau } R\left( t, \tau \right) ^{4} \right] \), respectively.

The (annualized) variance \(\sigma ^2\) is given by

Appendix B Truncation and discretization errors

The truncation and discretization errors are defined following AZ. For convenience, they are presented here.

As data from the options market are not continuous, the integral calculation of Eq. (A6) must be solved numerically. Using the trapezium rule, the integral can be discretized to

where

and m is the number of strikes. This discretization introduces errors. This slightly differs from CBOE’s discretization methods, as shown in the appendix, part C.

-

1.

Truncation errors

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned}&\int _{0}^{\infty }{\cdots dK} \rightarrow \int _{K_{\min }}^{K_{\max }}{\cdots dK} \\&\quad \text{ as } K\in \left( 0, \infty \right) \rightarrow K \in \left[ K_{\min }, K_{\max } \right] \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(B12)The range of strikes are finite; therefore, the range of the integral is truncated to the strikes that are available. This is tested by defining \(K_{\min }\) and \(K_{\max }\) as

$$\begin{aligned} \left[ K_{\min }, K_{\max } \right] := \left[ F_{t}^{T} \times a, F_{t}^{T} / a \right] \end{aligned}$$(B13)where \(a \in (0, 1)\) is the boundary controlling factor. So as \(a \rightarrow 0\), \(K_{\min } \rightarrow 0\) and \(K_{\max } \rightarrow \infty \) and as \(a \rightarrow 1\), \(K_{\min }, K_{\max } \rightarrow F_{t}^{T}\).

-

2.

Discretization errors

$$\begin{aligned} \int _{K_{\min }}^{K_{\max }}{\cdots dK} \rightarrow \sum _{K_{\min }}^{K_{\max }}{\cdots \Delta K_i} \end{aligned}$$(B14)To compute integrals numerically, the integrand and region must first be discretized. This can be done using the trapezium rule. This is not the only reason why discretizing is required. The other reason is that the strikes provided in the market is not continuous, but rather, usually in fixed intervals of $1, $5, $25, and $50.Footnote 9

Appendix C Numerical integration

The traditional trapezium rule is given in the form of Eq. (C15). With a small rearrangement, Eq. (C16) can be obtained. This is the trapezium rule that is used for calculations.

The CBOE uses Eq. (C17), which introduces a small error at the end points, \(K_{\min }\) and \(K_{\max }\). This method does, however, give equal weighting to each option—rather than half the weight given to end points if the traditional trapezium rule is used.

Appendix D Gram–Charlier region derivation

The Gram–Charlier density up to the kurtosis term, which is given by Eq. (2), can also be expressed in terms of Hermite polynomials and the standard normal distribution probability density function rather than the normal distribution and its derivatives. That is,

where He, the Hermite polynomial, is defined as

which gives \(He_{2}(x) = x^2 - 1\), \(He_{3}(x) = x^3 - 3x\), and \(He_{4}(x) = x^4 - 6 x^2 + 3\).

A necessary but not sufficient condition for f to be a valid probability density is that f must be positive semi-definite. As n(x) is already a valid density function, this condition is inherited by the Gram–Charlier density, that is,

Following Jondeau and Rockinger (2001), the boundary of the valid Gram–Charlier region can be found by finding \(\lambda _1\) and \(\lambda _2\), which satisfies

and

for all x. The \(\lambda _1\) and \(\lambda _2\) must simultaneously satisfy Eq. (D22) to ensure that \(p_{4}(x) = 0\) (where \(p_{4}(x)\) is the left-hand side of Eq. (D22)) and Eq. (D23) to ensure that adjacent values of \(\lambda _1\) and \(\lambda _2\) will also satisfy \(p_{4}(x) = 0\) for (infinitesimally) small variations of x. Equation (D23) can be found by taking the derivative of Eq. (D22) with respect to x. The explicit equations for \(\lambda _1\) and \(\lambda _2\), found from simultaneously solving Eqs. (D22) and (D23), are

These equations are used to plot the Gram–Charlier region in Figs. 1, 2, and 3.

Appendix E Additional variables under the Gram–Charlier density

1.1 E.1 CBOE VIX

The CBOE VIX can be calculated analytically using the Gram–Charlier density with the following proposition.

Proposition 2

Suppose that stock price is described by

where y is an extension of the standard normal distribution to include higher moments using the Gram–Charlier density and \(\mu _{c}\) is the convexity adjustment term. Then the VIX is given by

Proof

Demeterfi et al. (1999) present a method to replicate variance swaps with European options. Following part of their procedure, for a differential stock price form of

where r, q, and \(\sigma \) is risk-free rate, continuous dividend rate, and the volatility parameters, respectively, the following can be obtained:

With some algebraic manipulation, an intuitive formula can be found:

Using the integral form of stock price derived using the Gram–Charlier region, with some algebra, the following can be obtained.

\(\square \)

This proposition allows the variance swap to be calculated directly from the distribution of the returns, specifically, the moments and the time to maturity. For a stock price model with moments no higher than kurtosis, the VIX is given by

A simpler form of Eq. (E30) can be obtained by approximating the log and square root, as shown here:

By suppressing kurtosis, this formula shows that introducing negative skewness to returns will result in the VIX becoming smaller than the standard deviation. Originally, without kurtosis and skewness, the two were simply linked by a scaling factor.

The CBOE VIX is used as a benchmark against the VIX, calculated using the BKM method. This VIX can be calculated with

The volatility index can also be calculated using the BKM method:

where

As \(\mu \), the approximation of \(E_{t}^{\mathcal{Q}} \left[ R\left( t, \tau \right) \right] \), is required, this method introduces errors; however, it does remain model-free.

1.2 E.2 Rare disaster concern index

In this paper, the RIX is defined as

to include both upside and downside jumps. Originally in Gao et al. (2018), the RIX only included downside jumps:

The RIX is calculated from the difference of the variance of log returns (\({\mathbb{V}}\)) and the variance swap (\(\mathbb{I}\mathbb{V}\)).

1.3 E.3 Simple variance swaps

From Martin (2016), the SVIX is given by

where \(R_T = \frac{S_T}{S_t}\) and \(R_t = e^{r\tau }\). By setting \(q = 0\) and using a more general case of Eq. (2).Footnote 10

The SVIX can be decomposed with Carr and Madan (2001) to give

1.4 E.4 Errors of the additional variables

The VIX, RIX, and SVIX errors are shown in Table 10 with the errors of the BKM risk-neutral standard for comparison. From this table, the general trend of having a smaller error when the boundary controlling factor and step sizes are small holds; however, this trend is weaker for the RIX.

Appendix F BKM and Black-Scholes risk-neutral log returns

Using the standard Black-Scholes stock price model,

where \(B_{\tau }\) is the standard Brownian motion, the expected value of log returns is

From this, the BKM’s approximation can be compared like so:

As the BKM approximates the exponential term when used with \(R(t, \tau )\), this is also done to \(e^{r \tau }\). The result is

Expanding this further and simplifying, Eq. (7) can be obtained.

Appendix G Error envelope derivation

Using a simple curve was sufficient to capture the main characteristics of the error.

For \(y = \beta _1 x + \beta _2 x^2\)

For the positive envelope and negative envelope, the coefficients are assigned to \(\beta ^{+}\) and \(\beta ^{-}\), respectively. The symmetric envelope and trend can be found from \(\beta ^{s} = \frac{\beta ^{+} - \beta ^{-}}{2}\) and \(\beta ^{t} = \frac{\beta ^{+} + \beta ^{-}}{2}\), respectively. From this, the envelope component equations are given by

The positive and negative envelopes are therefore

To capture behaviour of the oscillations, the same quadratic model was used. Therefore, the coefficients were calculated the same way. The coefficient of the oscillations, denoted as \(\beta ^{\omega }\), forms the following oscillating function:

Combining the envelope, trend, and oscillating function forms the following model:

As \(X = \begin{bmatrix} x&x^2 \end{bmatrix}\), the model describes the error as changing quadratically in both the magnitude and period. Due to the specification of the model, when x (viz. \(\Delta K\)) is zero, the error vanishes.

Appendix H Errors from the volatility, cubic, and quartic contracts

The BKM method utilizes three contracts formed by Carr and Madan’s payoff decomposition function. To test the accuracy of the BKM estimators, the components within these estimators, the three contracts, can also be tested.

As the risk-neutral moments are known, the values of the contract can be calculated like so:

For this exact calculation, \(\displaystyle \mu = \left( r - \frac{1}{2} \sigma ^2 + \mu _c \right) \tau \), this uses the Black-Scholes and Gram–Charlier model (Eq. (8)). This can be used to test the accuracy of the calculation of each contract.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aschakulporn, P., Zhang, J.E. Bakshi, Kapadia, and Madan (2003) risk-neutral moment estimators: A Gram–Charlier density approach. Rev Deriv Res 25, 233–281 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11147-022-09187-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11147-022-09187-x