Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to examine whether morphological awareness measured before children are taught to read (Kindergarten in Israel) predicts reading accuracy and fluency in the middle of first grade, at the very beginning of the process of learning to read pointed Hebrew – a highly transparent orthography, and whether this contribution remains after controlling for phonemic awareness. In a longitudinal design, 680 Hebrew-speaking children were administered morphological and phonemic awareness measures at the end of the preschool year (before they were taught to read) then followed up into first grade when reading was tested in mid-year. The results indicated that even at this early point in learning to read a transparent orthography, preschool morphological awareness contributes significantly to both reading accuracy and reading fluency, even after partialling out age, non-verbal general ability, and phonemic awareness. The current results extend the Functional Opacity argument (Share, 2008) which proposes that at the initial stages of reading acquisition, when children still have incomplete mastery of some aspects of the spelling-sound system, non-phonological sources of information about word identity such as morphology can assist in the decoding process. The practical implications of these results with regard to early reading instruction are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is widely agreed that phonological awareness - the ability to analyze the constituent sounds in spoken words (such as phonemes, sub-syllabic units, and whole syllables), and in particular the awareness of phonemes (Ehri et al., 2001), is crucial for learning to read across orthographies (e.g., Bradley & Bryant, 1983 (English); Ho & Bryant 1997 (Chinese); Muller & Brady, 2001 (Finish); Pittas 2018 (Greek); Share & Levin 1999 (Hebrew); for review, see: Melby-Lervåg et al., 2012; Share, 2021). However, phonological awareness is not the only factor accounting for variance in reading ability (Duncan et al., 2019; Landerl et al., 2022; Levesque et al., 2020; McBride, 2015; Ruan et al., 2018; Verhoeven & Perfetti, 2011). A growing number of researchers have now demonstrated that morphological awareness, the ability to explicitly manipulate the morphemic structure of words (Bowers et al., 2010; Carlisle & Nomanbhoy, 1993; Nunes & Bryant, 2009), and/or morphological knowledge, the ability to produce inflected or derived forms when completing sentences (Nunes & Bryant, 2009), also contributes to reading in many languages, including English (Nagy et al., 2014; Nunes et al., 2003; Rastle, 2019); French (Casalis & Louis-Alexandre, 2000); Hebrew (Cohen-Mimran, 2009); Greek (Pittas & Nunes, 2014) and more (for review see Kirby & Bowers, in press).

It has been argued that the contribution of morphology to reading is subsumed by phonology (see, for example, Fowler & Liberman 1995; Shankweiler et al., 1995). Shankweiler et al., (1995) found that differences in reading ability (in English) were stronger when morphological distinctions were dependent on word-internal (phonemic) changes (e.g., sing/sang) compared to morphological distinctions that do not involve word-internal variation (e.g., play/played). According to this view morphological awareness (at least in English) accounts for little unique variance of reading after measures of phonological awareness are considered. An alternative view maintains that morphology makes a unique contribution to reading over and beyond its shared covariance with phonological awareness (Bowers & Bowers, 2017; Deacon & Kirby, 2004; Kirby et al., 2012; Nagy et al., 2006; Rastle, 2019). This approach emphasizes that morphological awareness is necessary to understand a writing system which represents morphological as well as phonological information. For example, in English the past tense verbal suffix < ed > is usually spelled consistently according to meaning and not sound –picked /t/ saved /d/ and patted (/ɛd/ (see also Berg & Aronoff, 2017).

The role of morphology in reading development

Several theorists have proposed that morphological awareness becomes relatively more important for word reading as children move beyond the initial stages of learning to read. Studies conducted among children learning to read English and other European languages indicate that morphological awareness contributes significantly to word reading from 2nd or 3rd grade (Deacon & Kirby, 2004; Hasenäcker et al., 2021; Kirby et al., 2012; Manolitsis et al., 2019; Nagy et al., 2006; Rastle, 2019; Verhoeven & Perfetti, 2011). The assumption is that morphological awareness affects reading when the children become more fluent readers and activate the “orthographic-semantic pathway” (see, e.g., Manolitsis et al., 2019) and when students encounter a growing number of complex words in texts (Rispens et al., 2008) and become more skilled in morphemic analysis (Nagy et al., 2014).

However, there are a few studies indicating that morphological awareness plays a roleat the beginning of reading acquisition as well. In general, children reach 1st grade with considerable morphological awareness (Berman, 2000; Berninger et al., 2010). When scripts represent morphemes of the spoken language in a clear, consistent, and distinguishable manner (Berg & Aronoff, 2017; Ravid & Schiff, 2006; Shimron, 2006), beginning readers who have very limited sight vocabularies can use morphological cues in reading in addition to phonological decoding (Burani et al., 2008). Apel & Lawrence, (2011) used a morphological awareness production task with derivational and inflectional suffixes to examine 44 English-speaking 1st graders. They found that morphological awareness as a concurrent predictor explained significant unique variance in word-level reading accuracy. This variance remained significant even after controlling non-verbal general ability, age, phonemic awareness, and letter knowledge. Similarly, Wolter et al., (2009) found that an oral morphological production task accounted for significant and unique variance in word reading accuracy among 43 English-speaking 1st graders, above and beyond that accounted for by phonological awareness. Consistent with these findings, Bowers et al., (2010) reviewed studies investigating the influence of morphological interventions on literacy learning and concluded that younger children (preschool to 2nd Grade) gain as much or more than the older students (3rd to 8th Grades) from explicit instruction of morphological knowledge. Notably, both these cross-sectional studies were undertaken in English – a highly (phonologically) opaque orthography that introduces considerable decoding difficulties for the beginning reader (Seymour et al., 2003). However, there appears to be inconsistent results in opaque scripts other than English regarding the role of morphological awareness in beginning reading. For example, assessing 123 French-speaking children, Sanchez et al., (2012) reported a small but significant contribution of morphological knowledge in kindergarten to first grade word reading accuracy after chronological age, non-verbal intelligence and vocabulary were controlled. However, Casalis & Louis-Alexandre (2000) who followed 50 French-speaking children from kindergarten to 2nd grade found that once age, IQ and vocabulary were controlled, morphological awareness measured in kindergarten contributed unique variance to a composite measure of text reading speed and accuracy only in Grade 2, but not in earlier grades. As for orthographies in which mappings between orthography and phonology are relatively consistent, the results are mixed. In a cross-sectional study in Dutch, Rispens et al., (2008) reported that awareness of noun morphology was a significant concurrent predictor of reading fluency among 104 Dutch speaking children in first grade. Manolitsis et al., (2017) followed 215 Greek speaking children from kindergarten to Grade 2 and reported that none of the MA skills tested predicted word reading fluency after controlling for the effects of vocabulary and RAN. In another study with Greek speaking children, Diamanti et al., (2017) followed 104 children from mid-kindergarten to the end of 1st grade. They found that beyond vocabulary and phonological awareness, a preschool morphological awareness composite score (judgment and production of inflectional suffixes and production of derivational suffixes) made a significant unique contribution to word and pseudoword reading accuracy but not to fluency near the end of 1st Grade.

Altogether, it seems that the role of morphological awareness in 1st grade reading is less clear compared to later grades. However, relatively few studies followed children from kindergarten to 1st grade. Additionally, it seems that while there are more consistent findings regarding the contribution of MA to word reading accuracy, findings regarding reading fluency (which is often the key outcome measure in regular orthographies) are inconsistent. In contrast to most research on this topic which has focused primarily on English or other Western European languages, our study was undertaken in Hebrew - a non-European (Semitic) language with a rich morphology and high morphological density. We examined the longitudinal connection between morphology assessed before children learn to read (i.e., Kindergarten in Israel) and early reading in Grade 1 in a large sample of Hebrew-speaking children.

Hebrew morphology

Hebrew is a Semitic (S)VO language with a highly productive morphology (Berman, 1985; Ravid, 1990). Hebrew allows inflection and conjugation through two morphological processes. One morphological process is the linear affixation of words. Linear word formation is created by linking morphemes to create a word: /maXʃeV/ ‘computer‘+ the plural suffix –im forms /maXʃeVim/ ’computers‘. In /maXʃeVon/ ’pocket calculator’, the diminutive suffix -on attaches to the noun. A second process is the nonlinear intertwining of a root and pattern, for example, /maXʃeV/ ‘computer’ is based on the combination of the root X-ʃ-V [ח.ש.ב.] and adjectival pattern ma-C-C-e-C. Combining roots and patterns yields the basic Hebrew word, creating morphological families based on roots - for example, the root X-ʃ-V in /XiʃuV/ ’calculation’, /meXuʃaV/ ’calculated’, /maXʃaVa/ ’a thought’(noun), and /XaʃaV/’thought’ (past tense verb); or based on patterns, such as the pattern Ma-C-C-e-C shared by /maXʃeV/’computer‘, /maGHeC/ ’iron’, /maʃPeX/ ’funnel’, and /maZReK/ ’syringe’. This is a nonlinear process because the root morpheme is inserted into a pattern instead of being linearly attached, as is common in Indo-European languages such as English. Understanding word formation in Hebrew requires sensitivity to both linear and nonlinear morphological structures (Ravid, 2006).

Because morphological processes are so crucial to Hebrew language acquisition, the ability of Hebrew-speaking children to identify and manipulate morphemic units in Hebrew begins to develop very early (Berman, 2000; Ravid, 2002). For example, Berman (2000) examined children’s creative knowledge of rule-based morphological processes in a sample aged 3–9 years. Results showed that by 3 years of age children coined novel nouns from verbs and by 4 years of age they coined novel verbs from nouns. This sensitivity continues to develop in elementary school (Levin et al., 2001; Ravid & Schiff, 2006).

The Hebrew abjad

The Hebrew writing system is an abjad or consonantal writing system (Daniels, 1992, 2018) which exists in two versions: pointed and unpointed (Ravid, 2006). In pointed Hebrew, many (but not all) vowels are represented by diacritical marks placed below, within, or above the letter. This script is used for beginning reading instruction and generally agreed to be highly regular and transparent. During 1st grade, the supplementary vowel signs offer the beginner reader a consistent, phonologically well-specified script and enable children to gain rapid mastery of the pointed script by the end of 1st grade (Share & Levin, 1999; Share, 2017). The unpointed script is the default version for native speakers who are proficient readers. Although the optional vowel signs are omitted in unpointed Hebrew, a small set of vowel letters convey a substantial amount of vowel information. From 3rd grade, children are expected to shift into the universally used unpointed version of written Hebrew.

The present study is a particularly strong test of the morphology-reading link because we examined whether preschool morphological awareness could predict reading skills at the very earliest stages of learning to read a transparent orthography, one in which letter-sound relationships are nearly perfect and hence allow readers to rely solely on simple one-to-one phonological decoding processes (Share, 2017; Share & Bar-On, 2018). Indeed, a number of studies (reviewed in Share & Levin 1999, and Share 2017) have shown that phonological awareness (subsyllabic and phonemic) is a significant predictor of early reading in Hebrew novice readers. Note that in Israel, unlike the US, Kindergarten is part of the pre-school education system and the preschool system (ages 3–5), and elementary schools (Grades 1 to 6) are entirely separate educational institutions (physically and administratively). Furthermore, Israeli children are not taught to read before they enter school in 1st Grade. In Kindergarten, pre-literacy activities may include familiarization with letters, or phonological awareness at the level of rhyme, core syllables (CV units) and initial and final consonants. Formal reading instruction begins in 1st Grade, around age 6, when children are introduced to the pointed (fully vocalized) Hebrew script. During 1st grade, reading instruction is based on letter-sound correspondences, but the unit of instruction is typically not the individual (consonantal) letter but an integral CV syllable “block” consisting of a consonant letter with a small (diacritic-like) vowel sign underneath (Share, 2017). Because our measures of morphological awareness were administered prior to the onset of reading instruction, our study represents a relatively clean test of the predictive status of morphological awareness unconfounded by potential reciprocal influences between morphological awareness and reading.

The role of morphology in learning to read Hebrew

Written Hebrew words consist of two distinct morphological layers, with an obligatory internal root core and an optional external ‘envelope’ of function letters (“clitics”). Furthermore, the architecture of the Hebrew writing system is uniquely designed to make roots visually salient. In contrast to English which has many different lexemes for semantically related words such as ‘play’ and ‘game’, Hebrew uses derivational devices that operate on a limited number of common tri-consonantal roots (/leSaXeK/ ‘to play’, /miSXaK/ ‘game’). Possibly because the lexical base of Old (Biblical) Hebrew mainly consisted of just three consonants, (allowing only 8000 (203) possible roots), the morphology bears the main burden of word-making. Many monomorphemic words (particularly Aramaic) entered the lexicon at a later stage, but the root-and-pattern word-formation infrastructure remains dominant. This system, in many ways, is the key to understanding the Hebrew writing system and the nature of learning to read and write in Hebrew (Share, 2017). Experienced Hebrew readers know that the lexically meaningful part of the word is represented in its core – the root, while letters framing the word carry grammatical and categorical meaning (Ravid & Schiff, 2006). Bar-On and Ravid (2011) have argued that morphological awareness is especially helpful in deep orthographies because it compensates for the ambiguous phonological information. This proposal aligns with evidence suggesting that dyslexics, who have well-known decoding difficulties, tend to rely heavily on morphology as a compensatory mechanism (Elbro & Arnbak, 1996; Law et al., 2015; Leikin & Even-Tzur, 2006). Along these lines, it has been proposed that morphological skills contribute to Hebrew reading when children use morphological pattern cues to fill in missing phonological information in unpointed words and overcome the difficulty of reading homographic words (Bar-On & Ravid 2011; Ravid & Schiff, 2006; Shimron, 2006).

As in many other languages, studies in Hebrew have demonstrated that morphology plays a special role in reading Hebrew from the end of 2nd grade (Cohen-Mimran, 2009; Ravid, 2012; see for a review Share 2017). For example, Schiff (2003) examined reading accuracy and rate of 150 Hebrew-speaking children from 2nd, 4th and 6th grade, and found that morphological complexity (feminine nominal derivations and feminine possessive optional inflections) influenced word identification accuracy and rate. Overall, inflections took longer to read and elicited more correct responses than derivations. In addition, Cohen-Mimran (2009) evaluated the contribution of language skills (semantics, morphology, and syntax) to reading fluency of pointed and unpointed texts among 48 Hebrew-speaking 5th graders and found that a morphological knowledge task (bound morphology) was the strongest predictor of reading fluency for both pointed and unpointed texts beyond phonological and memory skills. Vaknin-Nusbaum et al., (2016) explored the relationship between morphological awareness, word recognition and reading comprehension in a sample of 153 2nd and 5th graders, using the pointed form for 2nd graders, and unpointed form for 5th graders. The results revealed that in comparison to students with good morphological awareness skills, both 2nd and 5th grade students with low morphological awareness showed relatively poor performance in word recognition and reading comprehension. As for 1st graders, Levin et al., (2001) examined the contribution of morphological knowledge to writing skills among 40 Hebrew speaking children. Their results revealed that kindergartners who outperformed their peers in morphology tasks in kindergarten, progressed more in writing from kindergarten to 1st grade. To date, however, no study in Hebrew has examined the reading-morphology link among beginning readers, that is, in first grade.

The current study

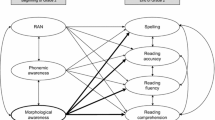

Most of the Hebrew studies that examined the influence of morphological awareness on reading were cross-sectional studies that investigated children after the initial stage of reading acquisition and particularly the stage when they are exposed to a growing volume of unpointed texts (Share & Bar-On, 2018). The present study adds to the existing research literature in two ways. First, we conducted a longitudinal study from preschool to 1st grade with a large sample of children. Examining the contribution of morphological abilities before children begin learning to read minimizes the effect of any reciprocal relations between morphological awareness and literacy skills that complicate the (cross-sectional) findings reported among 2nd and 3rd Grade children (Manolitsis et al., 2019). Second, we examined reading in the middle of 1st grade at the very beginning of the process of learning to read pointed Hebrew – a highly transparent orthography. Third, we examined the contribution of MA separately to reading fluency and reading accuracy. We also examined whether preschool morphological awareness predicts reading skill (speed and accuracy) after controlling for phonemic awareness. Controlling for phonemic awareness is essential because pointed Hebrew, as a highly regular transparent orthography, allows children at the beginning of reading acquisition to rely on phonological abilities to read. Moreover, in Hebrew, word-internal morphological changes, like the sing/sang and woman/women examples in English, involve individual phonemes. Mattingly (1985) even proposed that the Semitic origin of the alphabet may have been a product of these word-internal non-linear phoneme-level morphological structures/variations that characterize Semitic languages. A strong version of the morphology-reading link would predict that even after controlling for non-verbal general ability and phonemic awareness, morphological awareness will contribute uniquely and significantly to all reading outcome measures even at the very earliest stages of learning to read a transparent orthography.

Method

Participants

A total sample of 1,146 Hebrew-speaking children were recruited from 128 kindergartens in and around the greater Haifa region in the north of Israel, and later followed into their elementary schools typically located in the same neighborhood. The kindergartens were located in neighborhoods from diverse socio-economic strata, thus representing a highly heterogeneous SES background. In the first phase, all kindergartens in the Northern District and Haifa District were contacted and principals who agreed to cooperate were included in the study. In the second stage, all the children whose parents signed letters of consent to participate in the study were examined. Both regular (nonreligious) and religious Kindergartens were included, but not ultra-Orthodox (who follow an entirely different curriculum) or special education Kindergartens/schools. This cohort were followed up longitudinally from kindergarten to 1st Grade.

Six hundred and eighty children were tested on the entire test battery in the middle of 1st grade – before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic at which time (March, 13, 2020) schools were closed and testing eased. From the original sample of 1,146: 30 children were retained for an additional year in kindergarten, 6 children moved to special education, 10 families moved to a different region of the country, 5 children elected not to continue participating in the study and 415 children did not complete the tests before the schools were closed.

The participants consisted of 308 boys and 372 girls (Kindergarten: mean age 5.92 years, SD = 0.5; Grade 1: mean age 6.84 years, SD = 0.5). No child was excluded due to developmental or learning/attentional disorders or a non-Hebrew-speaking home background. Footnote 1

Ethical approval

for this study was granted by the Ministry of Education – Office of the Chief Scientist (permit #9667) and the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Education at the University of Haifa. Parents signed a consent form allowing their child to participate in the data collection.

Procedure

The measures described below were administered in two phases: morphological and phonemic awareness measures were administered at the end of the kindergarten year (May-June), and reading abilities were assessed in mid-1st Grade (January-March). The interval between the two phases was around 9 months.

All measures were administered individually in two sessions on different days of the same week as part of a broad battery that included language, arithmetic, executive functions, reading, and writing tasks. Each session took between 30 and 40 min depending on the child’s pace and was held in a quiet room in the kindergarten/school without the presence of the teacher/kindergarten teacher. The language tests were presented orally (without any accompanying written text). All examiners had a background in education, psychology, or speech pathology and underwent instruction and training in administering the tests at the Faculty of Education in Haifa University.

Materials

Kindergarten

Due to the fact that there are very few standardized developmental tests in Hebrew, almost all kindergarten measures were either developed from scratch by the authors or adapted from existing clinical or research instruments. The adaptation process was undertaken in two stages. In the first stage, the number of original items was reduced to meet the time constraints for administering the wider battery. Items were selected to be suitable for kindergarten children and also compatible with the tests in Arabic that were developed in parallel with the Hebrew tests. In addition, the adaptation of the derivation tasks included some changes in the paradigm: In the Verb Derivation task, the original task of deriving a noun from a verb was altered so that the children were asked to derivate verbs from nouns. In the Resultative Adjective Derivation task, the original task of deriving an adjective from an infinitive was altered to the derivation of adjectives from verbs. In both cases, the paradigm was adapted to create an easier task suitable for kindergarteners. In the second stage, these new adaptations (Morphology and Phonology) were piloted on a sample of 50 children and items were included (or excluded) based on item difficulty, internal consistency, and test-retest reliabilities. The number of items that remained in each task is reported in the test description.

Morphological awareness (MA) measures

In the morphological tasks, the child must recognize a morphological relationship in the first pair of words (verb/adjective; noun/verb; noun/noun) that were represented in a modeling sentence and then apply this relationship to the other pairs to generate the appropriate word to solve the morphological analogy between the words. Moreover, in the derivation tests there are multiple ways of completing the sentences that are semantically acceptable but only one correct derivation from base form. In order to achieve that, the child needs to explicitly derive the correct adjectival from the base verb form or the correct verb from the base noun form.

-

Resultative Adjective Derivation test - (Cohen-Mimran, Gott, Reznik-Nevet, & Share, 2018, adapted from Yegev 2001). The children were asked to derive 10 adjectives from given verbs. Before the test items were administered, the children were given two practice items with feedback: (1) “/XaTXu/ (They cut) the apple. Now the apple is __________ /XaTuX/, ‘cut’)”; (2) “/SiDRu/ (They organized) the books. Now the books are __________ (/meSuDaRim/, ‘organized’)”. A correct answer that included a correct derivation of the noun for the correct adjective, was reinforced (“Good”) followed by another repetition of the completed sentence by the tester. If an incorrect answer (or no answer) was given, the tester presented the correct form of derivation then repeated the entire completed sentence. One point was awarded for each correct derivation.

-

Verb Derivation test - (Cohen-Mimran, Gott, Reznik-Nevet, & Share, 2018, adapted from Novogrodsky & Kreiser 2015). In this task, children were asked to derive 8 verbal patterns according to the noun’s roots. The children were first presented with one modelling item (“What do we do with the /TSeVa/ (color)? With the /TSeVa/ /TSoV’ʕ’im/“), followed by one practice item: What do we do with the /meXaDeD/ (pencil sharpener)? With the pencil sharpener /meXaDeDim/. A correct answer that included a correct verb derivation, received a positive response (“Good”) from the tester and was followed by another repetition of the completed sentence. If an incorrect answer (or no answer) was given, the tester presented the correct derivation then repeated the entire sentence. One point was awarded if the child produced the correct derivation.

-

Noun Pluralization test (Cohen-Mimran, Gott, Reznik-Nevet, & Share, 2018; adapted from Lavie 2006; and Yegev 2001). This task requires the child to produce 15 plural forms from the singular noun forms, accompanied by pictures of objects (nouns). The test items included 5 regular forms (3 masculine and 2 feminine nouns) and 8 irregular forms (6 masculine and 2 feminine nouns) of the plural inflectional suffix in Hebrew. The target nouns included equal numbers of regular and irregular suffixes. An irregular suffix in Hebrew takes a plural marker of the opposite gender, e.g., the masculine noun /ʃulxɑn/ ’table‘ takes the feminine plural marker ‘ot’ to create /ʃulxɑnot/ ‘tables’. Target nouns also included unaltered stems as well as stem-internal changes. For example, the stem of the singular noun /ɛz/ ’goat‘ changes to /ɪz-im/ ‘goats’ when pluralized. Before test items were administered, the children were given two practice items: “Here is a ball /kadur/ (regular masculine noun). These are many_____ /kadurim/ (balls)”; “Here is one car /mexonit/ (regular feminine noun). These are lots of ______ /mexoniot/(cars)”. A correct answer received a positive response (“Good”), followed by repetition of the completed sentence with the correct inflection (“These are lots of balls/cars”). If an incorrect answer (or no answer) was given, the tester presented the correct plural form followed by the completed sentence. A correct answer was awarded one point.

We combined the three morphological measures using Principal Components Analysis. The first principal component accounted for 73.8% of the variance with high and very similar factor loadings (between 0.85 and 0.87) for each of the individual variables.

Phonemic awareness (PA) measures

Both PA measures were developed by the authors of this study. All test items were familiar real words chosen from a corpus of 50 words common among toddlers aged 1;4 to 3;3 collected from the Berman longitudinal corpus (Berman, 1990). As in other languages, access to sub-lexical phonological units including phonemes is a significant predictor of later reading ability (Share & levin, 1999). However, for the child who learns to read the Hebrew abjad, individual consonants and CV units are the critical elements of phonology (Share, 2017). It is also important to note that in Hebrew the initial consonants are intimately linked to the following vowel in an indivisible CV unit (Troyansky & Share, in preparation). Thus, at the beginning of learning to read phoneme awareness tasks include isolation of consonants that are not part of CV units, for example, initial consonant isolation in CCVC words as well as final consonant isolation in CVC words. To minimize extraneous cognitive demands, our tasks included only highly familiar words with only 3–4 phonemes. The number of phonemes was fixed. In the CVC test it was always 3 phonemes, and in the CCVC test 4 phonemes. Furthermore, we asked the child to repeat the word and gave a demonstration and three practice items with feedback before beginning the test items.

-

Initial consonant isolation in CCVC words (Share, Gott, Reznik-Nevet, & Cohen-Mimran, 2018). The children were asked to repeat a spoken target word and then to isolate the initial consonant. One demonstration item and four training items were presented before the task began. The 10 target items were CCVC words (e.g. say /dvaʃ/ ‘honey’ without /d/). A correct answer was awarded 1 point.

-

Final consonant isolation in CVC words (Share, Gott, Reznik-Nevet, & Cohen-Mimran, 2018). The children were asked to repeat the target word and then to isolate the final consonant. One demonstration item and four training items were presented before the task started. The 10 target items were CVC words (e.g. say /bat/ ‘girl’ without /t /). A correct answer was awarded by 1 point.

A single composite PA measure was developed on the basis of a Principal Components Analysis. The first principal component accounted for 80.9% of the variance, again with high and very similar factor loadings around the 0.90 mark for each of the two individual variables.

Grade 1.

Reading measures

Three tasks were used to assess the speed and accuracy of decoding real words and pseudowords (adapted from the Dutch One Minute Test (Brus & Voeten, 1973). Participants were asked to read aloud lists of words in 60 s and errors were manually recorded. Owing to the fact that, at this point in the year, children have typically been taught to decode all the Hebrew consonants but only the most common vowel signs, i.e., those representing /ɑ/, we developed three decoding measures: (1) The first list of words included 60 isolated and fully pointed (i.e., fully voweled) real words containing all the consonants but only the /ɑ/ vowel signs. These vowel signs account for around half of Hebrew’s vowel tokens; (2) The second list included 30 pseudowords varying in length and all containing only the vowel /ɑ/. This list was constructed on the basis of real words to ensure that all pseudowords preserve Hebrew’s morphological patterning; (3) The third list included 30 words containing the full inventory of vowel signs (13 in all). All words in the reading tests were fully pointed. The word lists appeared on the page in columns and all the words were displayed in the same font and size.

Out of 100 real words, 28 were multi-morphemic: 13 were verbs and 15 nouns. All verbs had a bimorphemic root-and-pattern structure (for example: קפץ: /KaFaTS/ ‘jumped’, past tense verb of the root K-F-TS). Among the nouns, 11 were root-and-pattern derivations (for example: /haTSLaXa/ ‘success’, the combination of root TS-L-X and the pattern haCCaCa) and four were inflected words (for example: /XaDaʃah/ female suffix –ah is added to the adjective /XaDaʃ/ ). The order of presentation was fixed; first the real words with vowel /ɑ/ list, then the pseudowords list and finally, the real words with all vowels. Each correctly pronounced word was awarded 1 point.

For each task, two different scores were calculated. One for fluency (the number of words read correctly in 60 s) and one for accuracy - the percentage of words correctly read out of the total number of words the subject attempted to read). Principal Components Analysis was also used to combine the three reading measures. The first principal component accounted for 86.6% of the variance with high and very similar factor loadings (between 0.92 and 0.95) for each of the fluency variables. For reading accuracy, the first principal component accounted for 75.9% of the variance, again with high and very similar factor loadings (between 0.82 and 0.91) for each of the individual accuracy variables.

Non-verbal general ability

The colored version of Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices was used to measure non-verbal ability (Raven, Raven, & Court, 1998). Following an explicit demonstration example, participants were asked to select the missing part of a geometric pattern from several alternatives. We administered all three sets in this test (18 items in total).

Results

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and reliabilities of all the measures. The morphological and phonemic measures were neither too easy nor too difficult, with no evidence of appreciable floor or ceiling effects. Also, most of the reliabilities for the morphology and PA measures were between 0.7 and 0.8. Thus, we can say that these data point to a fair comparison of morphology and phonology, one not confounded by differences in difficulty levels or score distributions.

The (vowel-) restricted reading scores showed that, as anticipated, most children had, by and large, mastered the Hebrew consonant letters (80%) and were able to correctly decode words when vowel signs were restricted to the default /ɑ/ signs that are taught at the beginning of first grade. Note that the success of pseudoword decoding (75%) indicates that word reading was not merely whole-word/logographic reading, but true decoding. When confronted with words containing the full range of vowel signs, reading accuracy dropped sharply to only 50% indicating that, as expected, at this mid-point in 1st Grade, the non-default vowel signs had not yet been mastered. These data are consistent with the existing research literature on early reading of pointed (fully-voweled) Hebrew (see, e.g., Share 2017) showing that the highly consistent pointed Hebrew orthography is rapidly mastered by most children as is the case with most orthographies with transparent letter-sound mapping (Seymour et al., 2003; Share, 2008). These findings also re-affirm that the major source of difficulty for young readers is the vowel signs (see Share 2017; for further discussion of this issue).

Both phonological awareness tasks proved to be rather difficult confirming the well-known finding that young children find it difficult to access phonemes prior to formal reading instruction in Grade 1 (Liberman et al., 1974; Share & Blum, 2005).

To investigate the relationships between the different reading, morphology, and phonology skills, we first report Pearson correlation coefficients between the composite variables (see Table 2). We emphasize that these are predictive-longitudinal correlations between the predictors measured before children learn to read and the outcomes measured after they have begun learning to read.

With the exception of age, significant correlations were found between all measures. Correlations between MA and reading accuracy and fluency were around the 0.3 mark, with somewhat stronger correlations for PA (0.42 and 0.49 for accuracy and fluency respectively). PA and MA were only weakly correlated (0.34), and, as predicted, reading accuracy and fluency were strongly correlated (partly owing to the fact that the fluency measure – words correct per minute, includes reading accuracy).

A unique contribution of morphology to reading

Separate hierarchical regressions were employed to explore the contribution of MA to early word reading accuracy and fluency. In each regression model, age and non-verbal general ability were entered in the first step to control for the possibility that any reading-language correlations may be spurious, an artefact of variance shared with general cognitive ability (Shatil & Share, 2003). We then assessed the unpartialled contribution of morphology, and then partialled out PA as well as the reverse – the unpartialled as well as partialled contribution of PA.

Reading accuracy

The results of the hierarchical regression predicting reading accuracy from age, non-verbal general ability, PA and MA are reported in Table 3. The results of step one indicated that the variance accounted for (R²) with the first two predictors (age and non-verbal general ability) was 10% and statistically significant. At the next step, the MA composite score was entered into the regression equation. This accounted for an additional and statistically significant 6% of the variance. At step 3, PA explained an additional 9% of the variance, which was statistically significant. When entered at Step 2 after age and non-verbal general ability, the PA composite score accounted for 13% of the variance in reading accuracy. At Step 3, MA added another statistically significant 2% of the variance over and above the contributions of age, non-verbal general ability, and PA.

Reading fluency

The results of the hierarchical regression predicting reading fluency from age, non-verbal general ability, PA, and MA, are reported in Table 4. A very similar pattern of findings emerged. At step 1, age and non-verbal general ability accounted for 9% of the variance in reading fluency. After controlling for age and non-verbal ability, MA added 7%, again statistically significant. At step 3, PA accounted for a further 13% of the variance. When entered at Step 2 after age and non-verbal general ability, PA explained 18% additional variance. At Step 3, MA once again accounted for 2% of the variance over and above the contributions of age, non-verbal general ability, and PA, and this was also statistically significant. These results indicate that most but not all the reading variance (fluency and accuracy) accounted for by morphology is shared with PA and hence is “swallowed up” once PA is entered at Step 2.

Discussion

The present study examined the contribution of MA to reading at the very earliest stages of reading acquisition in a highly transparent orthography. The results indicated that even at this early point in learning to read, pre-literate MA made a significant contribution to both their reading accuracy (6%) and to reading fluency (7%) which remained statistically significant even after partialling out age, non-verbal general ability, and PA. This is a particularly strong test of the morphology hypothesis because it was widely assumed that in the first year of learning to read pointed (fully transparent) Hebrew, children are relying exclusively on serial, letter by letter phonological recoding (decoding), and only in 2nd Grade does higher-order lexical and morpho-orthographic knowledge play a significant role in reading (Gur, 2005; Share & Bar-on, 2018). Our results confirm the central role of phonemic awareness at the initial stage of learning to read pointed Hebrew. However, despite the highly transparent pointed Hebrew script which allows young readers to rely heavily on the letter-sound decoding, MA still contributed significantly to reading achievement.

The results of the current study showing that MA assessed in kindergarten contributes to reading accuracy are in line with longitudinal studies from other languages. For example, reading accuracy in 1st grade was longitudinally predicted by preschool morphological awareness in French (Sanchez et al., 2012) and Greek (Diamanti et al., 2017). However, findings from the present study showed that MA examined in kindergarten also contributes to reading fluency in 1st grade. These results are in contrast to the findings of previous longitudinal studies in English (Manolitsis et al., 2019) and Greek) Diamanti et al., 2017; Manolitsis et al., 2017) found that early morphological awareness (Kindergarten) did not predict word reading fluency in 1st grade. Among English speakers, it has been shown that MA contributes to fluency only from 2nd grade and it was suggested that morphological awareness may not exert a significant effect on word reading fluency before children acquire an “orthographic-semantic pathway” (Manolitsis et al., 2019). Although Greek, like Hebrew, is a language with a transparent orthography and rich inflectional morphology (Diamanti et al., 2017; Pittas & Nunes, 2014; Protopapas & Vlahou, 2009), its characteristically Indo-European concatenative stem + affix derivational morphology differs markedly from Semitic non-concatenative root + pattern derivational morphology. In Hebrew, most nouns and all verbs are polymorphemic, consistent with a greater role for morphology in Hebrew reading acquisition. Other differences between these studies include the fact that Diamanti et al., (2017) measured text reading fluency and not single word reading speed, and the use of RAN as a control variable by Manolitsis et al., (2017). RAN is a particularly robust predictor of word reading fluency in beginning reading in transparent orthographies (e.g., Cohen-Mimran et al., 2021; Georgiou et al., 2008) partly because the two tasks share a time component which is crucial in reading fluency. Yet another explanation for the discrepant findings may relate to the children’s reading level at the time they were tested. Manolitsis et al., (2017) suggested that when decoding becomes effortless, children can read individual words fluently. However, in the current study, children were examined in the middle of the year when they were not yet fluent decoders as can be deduced from the relatively low reading accuracy of pseudowords. Our results may also reflect the strong interdependence between speed and accuracy at the very beginning of reading acquisition (r = .81). This explanation is also supported by Share’s (2008) Functional Opacity argument which proposes that at the initial stage of literacy acquisition in 1st grade, when children still have incomplete mastery of some aspects of the sound-spelling system, in particular the vowel signs, this makes the orthography functionally opaque (Share, 2008). This hypothesis was developed to explain the role of PA at the initial stage of literacy acquisition in first grade. However, the current results extend this hypothesis to MA. Thus, this functional (phonological) opacity may lead to higher reliance on alternative sources of information such as morphological cues including root letters, word-patterns, and inflectional morphemes (in addition to word-specific orthographic knowledge). In this context it is important to note that both the restricted-vowel measures on which children scored well (but still not at ceiling levels) as well as the more difficult unrestricted-vowel measure introduced a significant degree of functional opacity to the reading tasks. Moreover, even in the relatively simple word lists we used to test reading, there are many multi-morphemic words that contain familiar roots and morphological patterns, and thus morphological awareness and knowledge can affect word reading fluency and accuracy.

Indeed, a closer examination of the reading tests employed in the present study revealed that 28% of the words from the list of real words were morphologically complex. Furthermore, research has established that in Hebrew, young children are using morphological cuing very early in language development (Levie et al., 2020). Three-year-old Hebrew speakers with typical language development are able to extract the root from verbs (Clark & Berman, 1984) and can understand new verbs based on known nouns and adjectives (Berman, 2000). Thus, it seems logical that if there is morphological information that children can exploit while reading - at least some of them will use it.

Our study also draws attention to the need for a more nuanced formulation of the morphology-reading link, one that takes into account differences in the spoken language and the writing system. Orthographies differ not only in phonological transparency, but also in what might be termed “morphemic transparency” – the extent to which a given morpheme is consistently and distinctively spelled. For example, the spelling “constancy” (Rogers, 1995) or “uniformity” (Berg & Aronoff, 2017) of the base morpheme in park/parked compared to break/broke is likely to facilitate word learning and understanding in the same way that the Semitic tri-consonantal root remains (in most cases) invariant orthographically across derivations. With regard to the spoken language, the role of morphology in word-formation is considerably greater in Semitic root-and-pattern languages than in English. Thus, there may be different reasons why morphology contributes or fails to contribute to reading at a given age, and these differences have very different implications for instruction, assessment, and intervention.

Limitations

It can be argued that a 2% contribution to reading, even though it is statistically significant, is minimal to the point of trivial. First, it is important to note that PA and MA share some of their variance at this early age (e.g., Carlisle & Nomanbhoy 1993) and this may partly explain the relatively small amount of variance remaining to MA after PA entered the regression equation. When correlated variables are entered into hierarchical regression one after the other, all the shared variance is appropriated to the first variable, making the analysis an extremely conservative one. Second, we used a reading test that included isolated context-free word reading, where only 28% of the words in the real word lists were morphologically complex words, thus possibly reducing our chances of finding effects of MA on reading. Future research could examine the role of MA in reading words with different types of morphological complexity and also include reading in context (either sentences or paragraphs).

It should also be noted that the morphology measure used in the current study tap different skills – as we examined both inflection and derivation. In a future study it will be helpful to identify which measures of morphology – inflectional or derivational, are more strongly related to the different components of reading – word reading accuracy and fluency, text reading fluency and comprehension, and spelling. It seems a reasonable hypothesis that knowledge of derivational morphology would assist the reading of derived words, whereas inflectional morphology would be more helpful for reading inflected words and for morpho-syntactic integration of information within sentences.

Implications for practice

It is generally agreed that explicit instruction of the relationship between letters and sounds in the first years of reading instruction (i.e., systematic phonics) has a significant positive impact on reading success National Reading Panel, 2000; Bradley & Bryant, 1983). Recently, many have argued that specific instruction of morphological relationships may also improve reading performance (Bowers & Bowers, 2017; Carlisle, 2010; Kirby & Bowers, in press; Nunes et al., 2003). However, much less work has been conducted to specify at what point in reading development it should be delivered (Rastle, 2019) and cross-language comparisons of instruction in morphological awareness are needed to better understand the extent to which the association between morphological awareness and literacy development is language-dependent (Carlisle, 2010). Based on our findings we suggest that oral tasks and activities that foster children’s ability to find morphological relations between words and aim to increase their awareness of morphemes, roots and morphological patterns might be beneficial as early as kindergarten and the first year of reading instruction, in parallel with phonological skills training. Certainly, these assumptions need further investigation in a future study. Finally, the present data can be useful for the development of language measures in Hebrew for assessing phonological and morphological awareness among kindergarten and first grade children.

Notes

The overarching goal of our longitudinal study was to chart the growth of early reading (and writing, arithmetic, cognitive and linguistic) development in a large representative sample of Hebrew-speaking children with a special focus on a wide range of developmental disabilities/difficulties. Our team was primarily interested in learning disabilities/difficulties in all its varieties – dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, ADHD and DLD. It was crucial therefore to include the widest possible range of abilities and not exclude children experiencing difficulties or who were at-risk for future difficulties.

References

Apel, K., & Lawrence, J. (2011). Contributions of Morphological Awareness Skills to Word-Level Reading and Spelling in First-Grade Children with and without Speech Sound Disorder. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 54(5), 1312–1327. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0115)

Bar On, A., & Ravid, D. (2011). Morphological decoding in Hebrew pseudowords: A developmental study. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32, 553–581. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S014271641100021X

Berg, K., & Aronoff, M. (2017). Self-organization in the spelling of English suffixes: The emergence of culture out of anarchy. Language, 93(1), 37–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2017.0000

Berman, R. A. (1985). Acquisition of Hebrew. In D. I. Slobin (Ed.), The crosslinguistic study of language acquisition (pp. 255–271). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum

Berman, R. A. (1990). Berman Longitudinal Corpus. Department of Linguisitics, Tel Aviv University. Retrieved from: https://childes.talkbank.org/access/Other/Hebrew/BermanLong.html

Berman, R. A. (2000). Children’s innovative verbs vs. nouns: Structured elicitations and spontaneous coinages. In L. Menn, & N. Bernstein Ratner (Eds.), Methods for Studying Language Production (pp. 69–93). Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/swll.6.06ber

Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Nagy, W., & Carlisle, J. (2010). Growth in Phonological, Orthographic, and Morphological Awareness in Grades 1 to 6. Journal of Psycholinguist Research, 39, 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-009-9130-6. https://doi-org.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/

Brus, B. Th. &; Voeten, M.J.M. (1973). Een Minuut Test [One minute test]. Nijmegen:Berkhout

Bowers, J. S., & Bowers, P. N. (2017). Beyond phonics: the case for teaching children the logic of the English spelling system. Journal of Educational Psychology, 52, 124–141. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1288571

Bowers, P. N., Kirby, J. R., & Deacon, S. H. (2010). The Effects of Morphological Instruction on Literacy Skills: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 144–179. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0034654309359353

Burani, C., Marcolini, S., De Luca, M., & Zoccolotti, P. (2008). Morpheme-based reading aloud: Evidence from dyslexic and skilled Italian readers. Cognition, 108(1), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.12.010

Carlisle, J. F. (2010). Effects of instruction in morphological awareness on literacy achievement: An integrative review. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(4), 464–487. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.45.4.5

Carlisle, J. F., & Nomanbhoy, D. M. (1993). Phonological and morphological awareness in first graders. Applied Psycholinguistics, 14, 177–195. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716400009541

Casalis, S., & Louis-Alexandre, M. F. (2000). Morphological analysis, phonological analysis and learning to read French: a longitudinal study. Reading and Writing, 12, 303–335. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008177205648

Clark, E. V., & Berman, R. A. (1984). Structure and use in the acquisition of word formation. Language, 60, 542–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/413991

Cohen-Mimran, R. (2009). The contribution of language skills to reading fluency: A comparison of two orthographies for Hebrew. Journal of Child Language, 36(3), 657–672. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000908009148

Cohen-Mimran, R., Yifat, R., & Banai, K. (2021). Size matters? Rapid automatized naming of shape sizes, reading accuracy and reading speed. Journal of Research in Reading, 44, 882–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12376

Daniels, P. T. (1992). The syllabic origin of writing and the segmental origin of the alphabet. In P. Downing, S. D. Lima, & M. Noonan (Eds.), The linguistics of literacy (21 vol., pp. 83–110). Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Typological Studies in Language

Daniels, P. T., & Share, D. L. (2018). Writing system variation and its consequences for reading and dyslexia. Scientific Studies of Reading, 22(1), 101–116

Deacon, S. H., & Kirby, J. R. (2004). Morphological Awareness: Just “More Phonological”? The Roles of Morphological and Phonological Awareness in Reading Development. Applied Psycholinguistics, 25(2), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716404001110

Diamanti, V., Protopapas, A., Asimina Ralli, A. M., Antoniou, F., & Papaioannou, S. (2017). Preschool phonological and morphological awareness as longitudinal predictors of early reading and spelling development in Greek. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2039. https://doi-org.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02039

Duncan, L. G., Traficante, D., & Wilson, M. A. (Eds.). (2019). Word Morphology and Written Language Acquisition: Insights from Typical and Atypical Development in Different Orthographies. Lausanne: Frontiers Media. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/978-2-88945-832-5

Ehri, L., Nunes, S., Willows, D., Schuster, B., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T. (2001). Phonemic Awareness Instruction Helps Children Learn to Read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36, 250–287. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.36.3.2

Elbro, C., & Arnbak, E. (1996). The role of morpheme recognition and morphological awareness in dyslexia. Annals of dyslexia, 46(1), 209–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02648177

Fowler, A. E., & Liberman, I. Y. (1995). The role of phonology and orthography in morphological awareness. In L. B. Feldman (Ed.), Morphological aspects of language processing (pp. 157–188). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Georgiou, G. K., Parrila, R., & Papadopoulos, T. C. (2008). Predictors of word decoding and reading fluency across languages varying in orthographic consistency. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 566–580

Gur, T. (2005). Reading Hebrew vowel diacritics: A longitudinal investigation from Grade 1 to Grade 3 (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

Hasenäcker, J., Solaja, O., & Crepaldi, D. (2021). Does morphological structure modulate access to embedded word meaning in child readers? Memory & Cognition, 49(7), 1334–1347. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-021-01164-3

Ho, C. S. H., & Bryant, P. (1997). Phonological skills are important in learning to read Chinese. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 946–951. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.946

Kirby, J. R., Deacon, S. H., Bowers, P. N., Izenberg, L., Wade-Woolley, L., & Parrila, R. (2012). Children’s Morphological Awareness and Reading Ability. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 25(2), 389–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-010-9276-5

Kirby, J. R., & Bowers, P. N.Morphological Instruction and Literacy. In press

Landerl, K., Castles, A., & Parrila, R. (2022). Cognitive precursors of reading: A cross-linguistic perspective. Scientific Studies of Reading, 26(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2021.1983820

Lavie, N. (2006). Hebrew noun plurals in development. Unpublished master’s thesis, Tel Aviv University, Israel. (In Hebrew)

Law, J. M., Wouters, J., & Ghesquière, P. (2015). Morphological awareness and its role in compensation in adults with dyslexia. Dyslexia, 21(3), 254–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.1495

Leikin, M., & Even-Tzur, H. (2006). Morphological processing in adult dyslexia. Journal of psycholinguistic research, 35(6), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-006-9025-8

Levesque, K. C., Breadmore, H. L., & Deacon, S. H. (2020). How morphology impacts reading and spelling: Advancing the role of morphology in models of literacy development. The Journal of Research in Reading, 44(1), 10–26.https://doi-org.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/10.1111/1467-9817.12313

Levie, R., Ashkenazi, O., Eitan Stanzas, S., Zwilling, R. C., Raz, E., Hershkovitz, L., & Ravid, D. (2020). The route to the derivational verb family in Hebrew: A psycholinguistic study of acquisition and development. Morphology, 30(1), 1–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-020-09348-4

Levin, I., Ravid, D., & Rappaport, S. (2001). Morphology and spelling among Hebrew-speaking children: From kindergarten to first grade. Journal of Child Language, 28, 741–772. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000901004834

Liberman, I. Y., Shankweiler, D., Fischer, F. W., & Carter, B. (1974). Explicit syllable and phoneme segmentation in the young child. Journal of experimental child psychology, 18(2), 201–212

Manolitsis, G., Grigorakis, I., & Georgiou, G. K. (2017). The Longitudinal Contribution of Early Morphological Awareness Skills to Reading Fluency and Comprehension in Greek. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1793. doi: 0.3389/fpsyg.2017.01793

Manolitsis, G., Georgiou, G. K., Inoue, T., & Parrila, R. (2019). Are Morphological Awareness and Literacy Skills Reciprocally Related? Evidence from a Cross-Linguistic Study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(8), 1362–1381. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fedu0000354

Mattingly, I. G. (1985). Did orthographies evolve? Remedial and Special Education, 6(6), 18–23

McBride, C. (2015). Children’s Literacy Development: A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Learning to Read and Write. Routledge: Milton, UK

Melby-Lervåg, M., Lyster, S. A., & Hulme, C. (2012). Phonological skills and their role in learning to read: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 322–352. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026744

Müller, K., & Brady, S. (2001). Correlates of Early Reading Performance in a Transparent Orthography. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 14(7–8), 757–799. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012217704834. https://doi.org.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/

Nagy, W., Beminger, V. W., & Abbott, R. D. (2006). Contributions of morphology beyond phonology to literacy outcomes of upper elementary and middle-school students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 134–147. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0022-0663.98.1.134

Nagy, W. E., Carlisle, J. F., & Goodwin, A. P. (2014). Morphological knowledge and literacy acquisition. Journal of learning disabilities, 47(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022219413509967

Novogrodsky, R., & Kreiser, V. (2015). What can errors tell us about specific language impairment deficits? Semantic and morphological cuing in a sentence completion task. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 29(11), 812–825. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2015.1051239. https://doi-org.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/

Nunes, T., & Bryant, P. (2009). Children’s reading and spelling: Beyond the first steps. Wiley-Blackwell

Nunes, T., Bryant, P., & Olsson, J. (2003). Learning morpho logical and phonological spelling rules: An intervention study. Scientific Studies of Reading, 7(3), 289–307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532799XSSR0703_

Pittas, E. (2018). Longitudinal Contributions of Phonemic Awareness to Reading Greek Beyond Estimation of Verbal Ability and Morphological Awareness. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 34(3), 218–232. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2017.1390807

Pittas, E., & Nunes, T. (2014). The relation between morphological awareness and reading and spelling in Greek: a longitudinal study. Reading and Writing, 27, 1507–1527. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-014-9503-6

Protopapas, A., & Vlahou, E. L. (2009). A comparative quantitative analysis of Greek orthographic transparency. Behavior research methods, 41(4), 991–1008. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.991

Rastle (2019). The place of morphology in learning to read in English. Cortex; A Journal Devoted To The Study Of The Nervous System And Behavior, 116, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2018.02.008

Raven, J., Raven, J. C., & Court, J. H. (1998). Progressive matrices standard (PM38). Éditions du centre de psychologie appliquée

Ravid, D. (1990). Internal structure constraints on new-word formation devices in Modern Hebrew. Folia Linguistica, 24, 289–346. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/flin.1990.24.3-4.289

Ravid, D. (2002). A developmental perspective on root perception in Hebrew and Palestinian Arabic. In Y. Shimron (Ed.), Language processing and acquisition in languages of Semitic, root-based morphology (pp. 293–319). Amsterdam: John Benjamins

Ravid, D. (2006). Word-level morphology: A psycholinguistic perspective on linear formation in Hebrew nominals. Morphology, 16, 127–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-006-0006-2

Ravid, D. (2012). Spelling morphology: The psycholinguistics of Hebrew spelling (3 vol.). Springer Science & Business Media

Ravid, D., & Schiff, R. (2006). Morphological abilities in Hebrew-speaking gradeschoolers from two socio-economic backgrounds: An analogy task. First Language, 26, 381–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723706064828

Rispens, J. E., McBride-Chang, C., & Reitsma, P. (2008). Morphological awareness and early and advanced word recognition and spelling in Dutch. Reading and Writing, 21, 587–607. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-007-9077-7

Rogers, H. (1995). Optimal orthographies. In: Taylor I., Olson D.R. (eds), Scripts and literacy (pp. 31–43). Neuropsychology and Cognition, vol 7. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1162-1_3

Ruan, Y., Georgiou, G. K., Song, S., Li, Y., & Shu, H. (2018). Does writing system influence the associations between phonological awareness, morphological awareness, and reading? A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(2), 180–202. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/edu0000216

Sanchez, M., Magnan, A., & Ecalle, J. (2012). Knowledge about word structure in beginning readers: what specific links are there with word reading and spelling? European journal of psychology and educational research, 27, 299–317. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212

Schiff, R. (2003). The effects of morphology and word length on the reading of Hebrew nominals. Reading and Writing, 16(4), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023666419302

Seymour, P. H. K., Aro, M., & Erskine, J. M. (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 143–174. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712603321661859

Shankweiler, D., Crain, S., Katz, L., Fowler, A. E., Liberman, A. M., Brady, S. A., & Stuebing, K. K. (1995). Cognitive profiles of reading-disabled children: Comparison of language skills in phonology, morphology, and syntax. Psychological Science, 6(3), 149–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00324.x

Share, D. L. (2008). On the Anglocentricities of current reading research and practice: The perils of over reliance on an “outlier” orthography. Psychological Bulletin, 134(4), 584–615. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.584

Share, D. (2017). Learning to Read Hebrew. In L. Verhoeven, & C. Perfetti (Eds.), Learning to Read across Languages and Writing Systems (pp. 127–154). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316155752.007

Share, D. L. (2021). Common misconceptions about the phonological deficit theory of dyslexia. Brain Sciences, 11(11), 1510

Share, D. L., & Bar-On, A. (2018). Learning to Read a Semitic Abjad: The Triplex Model of Hebrew Reading Development. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(5), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219417718198. https://doi-org.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/

Share, D. L., & Blum, P. (2005). Syllable splitting in literate and preliterate Hebrew speakers: onsets and rimes or bodies and codas? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 92(2), 182–202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2005.05.003

Share, D. L., & Levin, I. (1999). Learning to read and write in Hebrew. In M. Harris, & G. Hatano (Eds.), Learning to read and write (pp. 89–111). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Shimron, J. (2006). Reading Hebrew: the language and the psychology of reading it. Routledge

Vaknin-Nusbaum, V., Sarid, M., & Shimron, J. (2016). Morphological awareness and reading in second and fifth grade: evidence from Hebrew. Reading and Writing, 29, 229–244. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9587-7

Verhoeven, L., & Perfetti, C. A. (2011). Morphological processing in reading acquisition: A cross-linguistic perspective. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32(3), 457–466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716411000154

Wolter, J. A., Wood, K. A., & D’zatko, K. W. (2009). The influence of morphological awareness on the literacy development of first-grade children. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 40, 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2009/08-0001)

Yegev, I. (2001). Preschool language skills: Comparing cleft palate children to healthy children their age. Thesis submitted for master’s degree (In Hebrew). Tel Aviv University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen-Mimran, R., Reznik-Nevet, L., Gott, D. et al. Preschool morphological awareness contributes to word reading at the very earliest stages of learning to read in a transparent orthography. Read Writ 36, 1845–1865 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10340-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10340-z