Abstract

Objective

To investigate associations between quality of life (QoL) and 1) immunotherapy and other cancer treatments received three months before QoL measurements, and 2) the comorbidities at the time of completion or in the year prior to QoL measurements, among patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

A cross-sectional study is conducted on patients with advanced cancer in the Netherlands. The data come from the baseline wave of the 2017–2020 eQuiPe study. Participants were surveyed via questionnaires (including EORTC QLQ-C30). Using multivariable linear and logistic regression models, we explored statistical associations between QoL components and immunotherapy and other cancer treatments as well as pre-existing comorbidities while adjusting for age, sex, socio-economic status.

Results

Of 1088 participants with median age 67 years, 51% were men. Immunotherapy was not associated with global QoL but was associated with reduced appetite loss (odds ratio (OR) = 0.6, 95%CI = [0.3,0.9]). Reduced global QoL was associated with chemotherapy (adjusted mean difference (β) = − 4.7, 95% CI [− 8.5,− 0.8]), back pain (β = − 7.4, 95% CI [− 11.0,− 3.8]), depression (β = − 13.8, 95% CI [− 21.5,− 6.2]), thyroid diseases (β = − 8.9, 95% CI [− 14.0,− 3.8]) and diabetes (β = − 4.5, 95% CI [− 8.9,− 0.5]). Chemotherapy was associated with lower physical (OR = 2.4, 95% CI [1.5,3.9]) and role (OR = 1.8, 95% CI [1.2,2.7]) functioning, and higher pain (OR = 1.9, 95% CI [1.3,2.9]) and fatigue (OR = 1.6, 95% CI [1.1,2.4]).

Conclusion

Our study identified associations between specific cancer treatments, lower QoL and more symptoms. Monitoring symptoms may improve QoL of patients with advanced cancer. Producing more evidence from real life data would help physicians in better identifying patients who require additional supportive care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite significant advances in medical oncology, more than a fifth of patients with cancer are diagnosed with metastases in the Netherlands [1]. Such patients often have a poor prognosis and need palliative care. Palliative care has been defined by the WHO as ‘an approach that improves the quality of life (QoL) of patients and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness’, such as metastasized cancer.

In palliative care settings, it is thus imperative to evaluate the effects of cancer treatments not only on patient’s survival, but also on their QoL. Traditionally, the effectiveness of cancer treatments has been evaluated in terms of disease-free and overall survival, and changes in tumour characteristics. More recently, the assessment of patient-reported physical and psychosocial outcomes has gained considerable importance, and it is now incorporated within many clinical trials [2,3,4,5], leading to a direct impact on clinical practice [6].

A paradigm shift has been observed in palliative treatments with the introduction of immunotherapy, but the determinants of its benefits on quality of life, adverse effects and survival are scarcely explored. Some randomised clinical trials have shown that side-effects of immunotherapy are often better tolerated than those of traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy [7], but it remains unclear whether this can be translated into a better QoL.

Therefore, identifying determinants of QoL, including adverse effects, is key to maintain or improve patients’ health related QoL [8], and in turn reduce hospitalisation. QoL is partly determined by patient- and tumour-related factors such as their socio-demographic characteristics, comorbidities and cancer treatments, and partly by psychological determinants, including coping mechanisms [9]. Population-based studies have revealed that patients’ socio-demographic characteristics such as age, sex and marital status may impact their QoL [10,11,12]. This was also observed in a randomised trial among advanced cancer patients [13]. Hence, the effect of cancer treatments on QoL outcomes may be confounded by such factors. Very little has been systematically done regarding post-treatment QoL in relation with immunotherapy [14]. There is limited published evidence from observational real-world data focusing on the impact of immunotherapy as well as of other cancer treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy an d surgery on QoL [10,11,12]. Moreover, patients with advanced cancer may have comorbidities which in turn have differential impact on their QoL [15]. The role of such comorbidities in the QoL of patients with advanced cancer patients has not been well studied. Using data from the eQuiPe study in the Netherlands, our aim is to investigate the associations between QoL components and 1) immunotherapy and other cancer treatments received three months before QoL measurements, and 2) the comorbidities at the time of completion or in the year prior to QoL measurements.

Methods

Data source

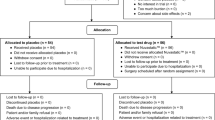

The data comes from the eQuiPe study [16] conducted by the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) in the Netherlands. Our analysis is cross-sectional and based on the baseline data of the eQuiPe study, which is originally a prospective longitudinal observational cohort of patients with metastatic cancer aiming to understand their QoL and improve care. eQuiPe is a nationwide study conducted in forty hospitals all over the Netherlands, where eligible patients filled questionnaires every three months regarding their QoL during their care. These questionnaires were filled between November 2017 to March 2020 and were further linked to the Netherlands Cancer registry (NCR) which is hosted by IKNL and is a nationwide population-based registry including all malignancies diagnosed since 1989. Trained data managers register patient-, tumour- and treatment-related characteristics directly from patient files. Questionnaires were used to collect information on possible additional treatments that were administered after diagnosis of the metastasis.

Inclusion criteria

Patients included in the eQuiPe study were aged 18 or over, able to complete a Dutch self-report questionnaire, understood the objectives of the eQuiPe research and consented to participate. Included patients were diagnosed with (progression of) a solid tumour with metastases (stage IV)[17] between 1988–2020. All sites of the primary tumour were considered for this study, including tumours of the respiratory and intrathoracic organs, digestive organs, male genital organs, and breast. However, additional criteria were applied for patients with breast or prostate cancer to minimise variation in life expectancy based on primary tumour type and overrepresentation of patients who have advanced cancer with relatively good prognosis. Hence, only breast cancer patients with metastases located in multiple organ systems and prostate cancer patients with metastasised and castration-resistant cancers were eligible. Patients who suffered from dementia or had a history of severe psychiatric illness were excluded.

Questionnaire

The EORTC QLQ-C30[18] questionnaire (version 3) is an integrated system for assessing the health related QoL of cancer patients participating in international clinical trials. This 30-item questionnaire assesses all 15 QoL components, namely, the global QoL, 5 functional scales (emotional, physical, social, role and cognitive), 8 symptom scales (pain, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, dyspnoea, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation and diarrhoea) and perceived financial impact of the disease. Some QoL components are derived from multiple questions, which are discussed in the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual [18]. The responses are recorded as raw scores on the Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = very much). Using linear transformations, these scores are converted to a continuous measure of scale ranging between 0 to 100 with higher scores representing higher global QoL/higher level of functioning/ higher level of symptoms.

Subsequently, socio-demographic variables, comorbidities, cancer treatments, recent hospitalisation and current symptoms were included in the eQuiPe questionnaire.

Outcome and covariables

Our main outcome of interest is QoL of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer.

There are two groups of exposures of interest, the first one being recent cancer treatments in the last three months since the survey which includes immunotherapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery and other treatments (like endocrine therapy). The second group of exposure is presence of individual comorbidities as listed in Table 1, either at the time of first questionnaire or developed in the past one year since the completion of the survey. Each of the treatments and comorbidities are coded separately as binary variables indicating presence/absence of treatment/comorbidity.

Covariables included demographic features such as sex, age (years), socio-economic status (SES) and marital status at the time of completion of the survey (in a relationship or single/widowed). SES was based on scores assigned to the four numbers of the Dutch postal code, extracted from the Netherlands Institute for Social Research. The scores arise from a principal component analysis on mean household income, percentage of inhabitants with a low income, percentage of low educatedness and percentage of unemployment [19]. The score was consequently coded into deciles. For this analysis, a SES score of 1–3 was recoded as ‘low’, 4–7 was ‘medium’ and 8–10 was recoded as ‘high’ SES.

Since the NCR holds no record on subsequent treatments (after nine months from diagnosis) given at the time of a metachronous metastasis (only if it is present at primary diagnosis), we do not include the treatments recorded by NCR and restrict our analysis to treatments based on the survey responses only.

Statistical analyses

Multivariable linear and logistic regression models were used to investigate the associations between 1) recent cancer treatments and different QoL components, and 2) comorbidities and QoL components, while controlling for possible confounder variables. A set of covariables sufficient for controlling the effects of confounding were selected via d-separation rules using a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). Although the limitations of the data do not allow us to draw causal conclusions, the DAGs (created using DAGitty v3.0 [20]) helped to identify important adjustment factors. For our analysis, we formed two separate DAGs, one to establish the adjusted total effects of recent cancer treatments on QoL components (Figure A.1) and the other to establish the effects of comorbidities on QoL components (Figure A.2). In both the DAGs, the exposure, outcome, other covariables and their associations known from the literature were first graphically depicted. Covariables – age, sex and SES were identified as adjustment factors in both the DAGs. Additionally, comorbidities confounded the effect of cancer treatments on QoL (Figure A.1), the recent cancer treatments were mediators in the path of comorbidities and QoL (Figure A.2) and hence were excluded from this analysis.

Model 1.1 depicts a multivariable linear regression model to study the effect of cancer treatments in the last three months on global QoL at baseline, adjusted for confounders like comorbidities in the past one year, age, sex and SES. Model 2.1 depicts a multivariable linear regression model to study the effect of comorbidities in the past one year on the global QoL at baseline while adjusting for age, sex and SES.

The scores on all 14 QoL components were not continuously distributed and hence, linear regression models are not an appropriate choice to model these outcomes. The functional scale scores are dichotomised as high/low level of functioning, symptom scale scores are dichotomised as presence/absence of symptom and financial difficulties score is dichotomised as yes/no, all using clinically relevant threshold values [21] (Table 2B,C). In Model 1.2, we fit 14 separate multivariable logistic regression models to study the effect of cancer treatments on the various QoL components, adjusted for comorbidities, age, sex and SES and in Model 2.2, we fit 14 separate multivariable logistic regression models to study the effect of comorbidities on the various QoL components. A histogram with a superimposed normal curve was used to check the normality of residuals assumption of linear models and the Hosmer–Lemeshow [22] test was used to assess goodness of fit of the logistic regression models. We did not perform multiple testing as our analysis was exploratory.

Since the variable `depression’ is a component of the emotional functioning outcome, we excluded it while estimating the effects of cancer treatments and comorbidities on the `emotional’ functioning. Similarly, comorbidities like back pain and asthma were excluded from the models with outcome variable ‘pain’ and `dyspnoea’ respectively.

Subgroup analyses by tumour site (Appendix B) were performed to assess potential differences in the effect of exposure on QoL. The ICD-10 codes of primary tumours were categorised by site and only the top two most prevalent tumour sites were considered for subgroup analysis.

All analyses were performed using RStudio software version 4.0.4 [23].

Results

The population comprises 1,089 patients diagnosed with solid metastasised (stage IV) primary tumours of any site, between 1988–2020. Patients’ characteristics, tumour site, recent cancer treatments in the previous three months and comorbidities in the past year are presented in Table 1. One participant did not meet the criteria of diagnosis of solid primary tumour and was thus excluded leaving us with 1,088 participants. Nearly equal number of men (n = 554,51%) and women with median age of 67 years [IQR = (60,73)] at baseline participated. There were 657 (60.4%) patients who had treatment(s) in the last three months prior to the baseline survey, 298 (27.4%) underwent surgery, a fifth received immunotherapy (n = 208,19.1%), 144 (13.2%) received chemotherapy, 58 (5.3%) received other treatments and 37 (3.4%) received radiotherapy. Comorbidities such as high blood pressure (238,21.9%) and back pain (170,15.6%) were most prevalent. Table 2 presents the results for the global QoL scores (mean (SD) and median [IQR]) and dichotomised scores of functional and symptom scales using clinical thresholds [21]. The median global QoL score was 66.7 [58.3,83.3].

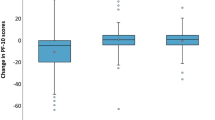

Association between treatment and QoL

Treatments are differently associated with global QoL. Immunotherapy treatment (vs no immunotherapy) was not associated with a lower or higher global QoL (Model 1.1, Fig. 1). No clear association was found between immunotherapy and having clinically relevant problems on the different functional components (Model 1.2, Fig. 2), while immunotherapy had lower odds of clinically relevant appetite loss (OR = 0.6,95%CI = [0.3,0.9]) (Fig. 3). Recent chemotherapy was associated with a lower global QoL (β = − 4.7,95%CI = [− 8.5,− 0.8]) and also related to higher odds of low role functioning (OR = 1.8,95% CI = [1.2,2.7]) and low physical functioning (OR = 2.4,95%CI = [1.5,3.9]). Moreover, chemotherapy was related with higher odds of more fatigue (OR = 1.5,95%CI = [1.1,2.4]) and more pain symptoms (OR = 1.9,95%CI = [1.3,2.9]). Radiotherapy was related to lower odds of low emotional (OR = 0.4,95%CI = [0.1,0.9]) and low physical functioning (OR = 0.3,95%CI = [0.1,0.7]) and more dyspnoea (OR = 0.4,95%CI = [0.2,0.9]).

The results from subgroup analysis overall generally agreed with the full analysis. Among patients with respiratory and intrathoracic tumours, chemotherapy was associated with reduced social functioning and increased nausea/vomiting symptoms while radiotherapy was associated with better global QoL (Table B.1). Among patients with cancers of digestive organs, there was evidence of an association between radiotherapy and increased diarrhoea symptoms while immunotherapy was related to lower diarrhoea (Table B.2).

Association between comorbidities and QoL

Analysis of comorbidities revealed a strong association between the presence of comorbidities and global QoL in patients with advanced cancer (Model 2.1), such as back pain (β = − 7.4,95%CI = [− 11,− 3.8]), depression (β = − 13.8,95%CI = [− 21.4,− 6.1]), thyroid disease (β = − 8.9,95%CI = [− 14,− 3.8]) and diabetes (β = − 4.5,95%CI = [− 8.9,− 0.1]). Back pain and depression showed a strong association with physical, role and cognitive functioning (Model 2.2, Fig. 2). Asthma/COPD was strongly associated with higher odds of low social (OR = 1.9,95%CI = [1.2,3.2]), low physical (OR = 1.8,95%CI = [1.1,3]) and low cognitive (OR = 1.6,95%CI = [1,2.6]) functioning as well as more insomnia (OR = 2,95%CI = [1.2,3.4]). Anaemia/other blood conditions were associated with higher odds of more constipation (OR = 4.9,95%CI = [2.2,10]). There was no association between global QoL and comorbidities like arthritis, ulcers and stroke/CVA. The full results are shown in Figs. 1, 2 and 3.

All linear models satisfied the normality of residuals assumptions and all logistic regression models were a good fit as per the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test.

Discussion

Patient-reported outcomes and QoL indicators are paramount in assessing the impact of treatments and comorbidities on the QoL of cancer patients. This cross-sectional study was primarily aimed at finding associations between immunotherapy and other cancer treatments and QoL of patients with advanced cancer. Such patients are restricted in their QoL due to their diagnosis and potential treatment-related side-effects. Physicians are aware of this fact [24] and research efforts as well as clinical practice are being mounted towards optimising patients’ QoL. Identification of cancer treatments and comorbidities associated with QoL measures may help minimise the decline in patients’ QoL.

Our study showed that over a third of patients scored below the threshold level on the physical and role functioning scales and above the threshold level on dyspnoea, fatigue and pain symptom scales. Moreover, studies with more focused populations with respect to cancer sites also reported symptoms including fatigue [25], dyspnea [25], pain [25] and insomnia [25, 26] after treatment for advanced cancer. We also observed associations between specific treatments and QoL components, as also observed in the limited literature, for example among breast cancer survivors [15].

QoL of cancer patients with advanced cancer following immunotherapy has only received limited and recent attention in research, despite its importance [27, 28]. Our statistical analysis did not find strong associations between immunotherapy and lower global QoL or its functional components. However, immunotherapy maybe associated with less appetite loss, although there was weak evidence for it. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies indicating lower appetite loss after immunotherapy while loss of appetite has been commonly reported after chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery [29]. Moreover, PD-(L)1 inhibitors like nivolumab, pembrolizumab and atezolizumab have been observed to be associated with consistent delay in time to symptomatic deterioration in QoL among patients with solid tumours [30] compared to traditional cytotoxic therapy. This was also reflected in our study where we could not see a significant impact of immunotherapy on QoL at baseline while chemotherapy was associated with poorer global QoL, and lower physical and role functioning. This association has also been observed among patients with breast or colon cancer [31] and colorectal cancer [32] who were assessed before and after their first cycle of chemotherapy. However, we did not observe any significant association between chemotherapy and emotional, social and cognitive functioning in this study. Pain is a common side-effect of chemotherapy [33, 34] which was also observed in our study. In contrast with a single-centre study in Brazil with 84% women with breast cancer [35], our study did not show significant positive association between chemotherapy and constipation symptoms. Another study on rectal cancer patients showed that radiotherapy significantly increased diarrhoea, fatigue and appetite loss and reduced physical and role functioning and global QoL at the end of radiotherapy [36]. In our data, we observed that radiotherapy was associated with increased diarrhoea among a broader category of patients with cancer of the digestive organs, possibly reflecting radiation enteritis of which diarrhoea is one of the most commonly reported symptoms (Table B.2). It is also expected to observe increased nausea and vomiting in patients with respiratory and intrathoracic tumours who received chemotherapy. In our data, lung cancer represented 97% of these tumours, for which the most common chemotherapy drug combinations used include cisplatin, and often carboplatin, which are both emetogenic.

Our analysis did not indicate any significant association between immunotherapy and lower QoL during or just after administration as opposed to chemotherapy. Early integration with palliative care has shown better patient outcomes in terms of improved care through frequent monitoring of symptoms and functional status, timely intervention for troubling symptoms, better QoL and prolonged survival [37]. Evidence from clinical trials suggests that immunotherapy is generally well-tolerated but this evidence is mostly based on patients selected on their good performance status [38]. It can also be attributed to the fact that immunotherapy maybe administered to patients who are in better health condition.

Higher levels of social support given to patients is associated with better QoL [39], and social support tends to decrease with lower SES [40], which highlights the importance of the role of social support in more deprived patients. Moreover, effective social support systems can help reduce feelings of social isolation so patients can strive for normality [41].

Strengths and limitations

In addition to the reasonable large study population, this nation-wide collaborative study also included a range of teaching and general hospitals and a good geographic spread, likely to be representative of the various care settings in the Netherlands.

The recruitment of patients in this study was completed in the year 2020 before the Covid-19 pandemic, however, the follow-up of patients was affected. In this study we have analysed the baseline data, which is not affected by the pandemic. The cross-sectional design of this study allowed us only to estimate associations with QoL, instead of any causal relationships. There is scope for selection bias as patients with better outcomes/ higher QoL were more likely to participate in the study than patients with lower QoL [42]. Moreover, this selection bias may have increased if the health care professional asked only patients with higher QoL to take part in the study. If the condition of the patient deteriorated after treatment, their participation would have been dramatically reduced. The length of the questionnaire could have led to a higher drop-out rate, especially among patients with more symptoms or poorer QoL. However, a meta-analysis showed no obvious indication that response rates are attributable to the length of the questionnaire [43]. This analysis is based on patient-reported cancer treatments, and it is possible that some patients may not be fully aware of their treatments. Moreover, we lacked information on the complete treatment history and only considered cancer treatments administered in the last three months, which might have affected our results. Lastly, some patients may have expressed difficulty in quantifying their level of symptoms [44].

Conclusions and recommendations for clinical practice

Our findings suggest that immunotherapy was not associated with lower QoL, while chemotherapy was associated with lower QoL. As chemotherapy was associated with more pain and fatigue, monitoring these symptoms is important and may improve QoL of patients with advanced cancer. The associations of comorbidities such as back pain, diabetes, thyroid diseases and depression with lower QoL might also help identify patients who require additional care. In addition, it is vital to discuss both the advantages and potential harms of palliative treatments on QoL with patients in the treatment decision-making process and those should be re-evaluated regularly. However, decision making is largely informed by randomised trial data, which are heavily biased due to their strict inclusion criteria. It implies that evaluation of expected benefits and harms (e.g. by measuring QoL) based on real life data is urgently needed. The impact of social support on QoL can be further explored with the eQuiPe study.

Data Availability

Since 2011, PROFILES registry data is freely available according to the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles for non-commercial (international) scientific research, subject only to privacy and confidentiality restrictions. The datasets analysed during the current study are available through Questacy (DDI 3.x XML) and can be accessed by our website (www.profilesregistry.nl). In order to arrange optimal long-term data warehousing and dissemination, we follow the quality guidelines that are formulated in the ‘Data Seal of Approval’ (www.datasealofapproval.org) document, developed by Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS). The underlying data of this manuscript would be made available when the eQuiPe study is completed.

References

Nederland, i.k. Little progress in metastatic cancer. 2020 5 October 2022]; Available from: https://iknl.nl/nieuws/2020/uitgezaaide-kanker-in-beeld.

Bottomley, A., et al. (2004). Randomized, controlled trial investigating short-term health-related quality of life with doxorubicin and paclitaxel versus doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide as first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Group, Investigational Drug Branch for Breast Cancer and the New Drug Development Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(13), 2576–2586.

Bottomley, A., et al. (2006). Short-term treatment-related symptoms and quality of life: Results from an international randomized phase III study of cisplatin with or without raltitrexed in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: an EORTC Lung-Cancer Group and National Cancer Institute, Canada. Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol, 24(9), 1435–1442.

Taphoorn, M. J., et al. (2005). Health-related quality of life in patients with glioblastoma: a randomised controlled trial. The lancet Oncology, 6(12), 937–944.

van Meerbeeck, J. P., et al. (2005). Randomized phase III study of cisplatin with or without raltitrexed in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: an intergroup study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Lung Cancer Group and the National Cancer Institute of Canada. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(28), 6881–6889.

Kotronoulas, G., et al. (2014). What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? a systematic review of controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(14), 1480–1501.

Magee, D. E., et al. (2020). Adverse event profile for immunotherapy agents compared with chemotherapy in solid organ tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Annals of Oncology, 31(1), 50–60.

Suarez-Almazor, M., et al. (2021). Quality of life in cancer care. Med (N Y), 2(8), 885–888.

Zimmermann, C., et al. (2011). Determinants of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 19(5), 621–629.

Brazier, J. E., et al. (1992). Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ, 305(6846), 160–164.

Jenkinson, C., Coulter, A., & Wright, L. (1993). Short form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 306(6890), 1437–1440.

Hjermstad, M. J., et al. (1998). Health-related quality of life in the general Norwegian population assessed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire: the QLQ=C30 (+ 3). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16(3), 1188–1196.

Jordhøy, M. S., et al. (2001). Quality of life in advanced cancer patients: The impact of sociodemographic and medical characteristics. British Journal of Cancer, 85(10), 1478–1485.

Beaulieu, E., et al. (2022). Health-related quality of life in cancer immunotherapy: a systematic perspective, using causal loop diagrams. Quality of Life Research, 31(8), 2357–2366.

Fu, M. R., et al. (2015). Comorbidities and quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a prospective study. J Pers Med, 5(3), 229–242.

van Roij, J., et al. (2020). Prospective cohort study of patients with advanced cancer and their relatives on the experienced quality of care and life (eQuiPe study): a study protocol. BMC Palliative Care, 19(1), 139.

AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8 ed, ed. S.B.E. Mahul B. Amin, Frederick L. Greene, David R. Byrd, Robert K. Brookland, Mary Kay Washington, Jeffrey E. Gershenwald, Carolyn C. Compton, Kenneth R. Hess, Daniel C. Sullivan, J. Milburn Jessup, James D. Brierley, Lauri E. Gaspar, Richard L. Schilsky, Charles M. Balch, David P. Winchester, Elliot A. Asare, Martin Madera, Donna M. Gress, Laura R. Meye. Springer Cham. 1032.

Fayers P.M., A.N., Bjordal K., Groenvold, M., Curran, D., & Bottomley, A., on and b.o.t.E.Q.o.L. Group. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (3rd Edition).Manual. 2001 [cited 2021; Third: [Available from: https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/SCmanual.pdf.

Research., N.I.f.S. Socio-Economic Status by postcode area. 08–03–2019 [cited 2022; Available from: https://bronnen.zorggegevens.nl/Bron?naam=Sociaal-Economische-Status-per-postcodegebied.

Johannes Textor, B. V. D. Z., Gilthorpe, M. K., Liskiewicz, M., & Ellison, G. T. H. (2016). Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package “dagitty.” International Journal of Epidemiology., 45(6), 1887–1894.

Giesinger, J. M., et al. (2020). Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 118, 1–8.

Lemeshow, S., & Hosmer, D. W., Jr. (1982). A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. American Journal of Epidemiology, 115(1), 92–106.

(2020), R.T. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. 2020 [cited 2021; Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/.

Hamann, H. A., et al. (2013). Clinician perceptions of care difficulty, quality of life, and symptom reports for lung cancer patients: an analysis from the Symptom Outcomes and Practice patterns (SOAPP) study. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 8(12), 1474–1483.

Gough, N., et al. (2017). Symptom Burden in Advanced Soft-Tissue Sarcoma. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53(3), 588–597.

Gentry, M. T., et al. (2020). Effects of a multidisciplinary quality of life intervention on sleep quality in patients with advanced cancer receiving radiation therapy. Palliative & Supportive Care, 18(3), 307–313.

Taarnhøj, G. A., et al. (2020). Patient reported symptoms associated with quality of life during chemo- or immunotherapy for bladder cancer patients with advanced disease. Cancer Medicine, 9(9), 3078–3087.

Voon, P. J., Cella, D., & Hansen, A. R. (2021). Health-related quality-of-life assessment of patients with solid tumors on immuno-oncology therapies. Cancer, 127(9), 1360–1368.

Ukovic, B., & Porter, J. (2020). Nutrition interventions to improve the appetite of adults undergoing cancer treatment: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(10), 4575–4583.

Abdel-Rahman, O., Oweira, H., & Giryes, A. (2018). Health-related quality of life in cancer patients treated with PD-(L)1 inhibitors: A systematic review. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, 18(12), 1231–1239.

Zamel, O. N., et al. (2021). Quality of life among breast and colon cancer patients before and after first-cycle chemotherapy. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 39(2), 116–125.

Tabata, A., et al. (2018). Changes in upper extremity function, ADL, and HRQoL in colorectal cancer patients after the first chemotherapy cycle with oxaliplatin: a prospective single-center observational study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(7), 2397–2405.

Al-Mazidi, S., et al. (2018). Association of Interleukin-6 and Other Cytokines with Self-Reported Pain in Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Chemotherapy. Pain Medicine, 19(5), 1058–1066.

Ventzel, L., et al. (2016). Chemotherapy-induced pain and neuropathy: a prospective study in patients treated with adjuvant oxaliplatin or docetaxel. Pain, 157(3), 560–568.

Lisboa, N. D., I, et al. (2021). Constipation in chemotherapy patients: a diagnostic accuracy study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 22(9), 3017–3021.

Guren, M. G., et al. (2003). Quality of life during radiotherapy for rectal cancer. European Journal of Cancer, 39(5), 587–594.

Temel, J. S., et al. (2010). Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(8), 733–742.

Khaki, A. R., Glisch, C., & Petrillo, L. A. (2021). Immunotherapy in patients with poor performance status: the jury is still out on this special population. JCO oncology practice, 17(9), 583–586.

Applebaum, A. J., et al. (2014). Optimism, social support, and mental health outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 23(3), 299–306.

Melchiorre, M. G., et al. (2013). Social support, socio-economic status, health and abuse among older people in seven European countries. PLoS One, 8(1), e54856.

van Roij, J., et al. (2019). Social consequences of advanced cancer in patients and their informal caregivers: a qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(4), 1187–1195.

de Rooij, B. H., et al. (2018). Cancer survivors not participating in observational patient-reported outcome studies have a lower survival compared to participants: the population-based PROFILES registry. Quality of Life Research, 27(12), 3313–3324.

Rolstad, S., Adler, J., & Rydén, A. (2011). Response burden and questionnaire length: Is shorter better? a review and meta-analysis. Value Health, 14(8), 1101–1108.

Campbell, R., et al. (2022). Perceived benefits and limitations of using patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice with individual patients: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Quality of Life Research, 31(6), 1597–1620.

Mackay, T. M., et al. (2020). Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life Before and After Treatment of Pancreatic and Periampullary Cancer: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 18(6), 704–711.

van Roij, J., et al. (2022). Quality of life and quality of care as experienced by patients with advanced cancer and their relatives: A multicentre observational cohort study (eQuiPe). European Journal of Cancer, 165, 125–135.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who consented to participate in the study as well as the eQuiPe study group for sharing their data with us. We also thank the registry team of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) and the PROFILES team for collecting data for the Netherlands Cancer Registry and linking it to the data collected by eQuiPe study group. We are very grateful to the reviewers of our study for their positive comments and suggestions which enhanced the clarity of this paper.

Funding

AM is funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 875171. MQ and BR are funded through the Cancer Research UK Population Research Committee Funding Scheme: Cancer Research UK Population Research Committee—Programme Award (C7923/A18525 and C7923/A29018). CL is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (Skills Development Fellowship MR/T032448/1). NR, MV and the eQuiPe study were supported by the Roparun Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: Ananya Malhotra, Clemence Leyrat, Manuela Quaresma, Bernard Rachet and Marissa C. van Maaren. Methodology: Ananya Malhotra, Clemence Leyrat, Manuela Quaresma and Bernard Rachet. Formal analysis: Ananya Malhotra. Data curation: Ananya Malhotra, Heidi Fransen. Writing – original draft: Ananya Malhotra. Writing – review and editing: all co-authors. Supervision: Clemence Leyrat, Manuela Quaresma and Bernard Rachet.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors of this study declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This study was approved by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Research Ethics Committee [45] and the privacy committee of the Netherlands Cancer Registry (request number K20.400). The underlying data is from the eQuiPe study [46] that was conducted by IKNL according to the declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, in data collection and analyses procedures, the rules of Dutch Personal Data Protection Act and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) were followed. In all collaborating hospitals, local scientific committees, if present, were contacted to get local approval and a check for competitive studies was done in consultation with the concerned department. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent to participate (include appropriate statements)

All patients participating in the study provided an informed written consent.

Consent for publication (include appropriate statements)

All patients participating in the study provided an informed written consent. All co-authors approved to publish this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malhotra, A., Fransen, H.P., Quaresma, M. et al. Associations between treatments, comorbidities and multidimensional aspects of quality of life among patients with advanced cancer in the Netherlands—a 2017–2020 multicentre cross-sectional study. Qual Life Res 32, 3123–3133 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03460-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03460-8