Abstract

We use experimental data to explore the conditions under which males and females may differ in their tendency to act corruptly and their tolerance of corruption. We ask if males and females respond differently to the tradeoff between the benefits accrued by corrupt actors versus the negative externality imposed on other people by corruption. Our findings reveal that neither males nor females uniformly are more likely to engage in, or be more tolerant of corruption: it depends on the exact bribery conditions—which can reduce or enhance welfare overall—and the part played in the bribery act. Females are less likely to tolerate and engage in corruption when doing so reduces overall welfare. On the other hand, males are less tolerant of bribery when it enhances welfare but confers payoff disadvantages on them relative to corrupt actors. Females’ behavior is consistent across roles when bribery reduces welfare, but apart from that, gender behavior is strongly role-dependent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Do women behave as corruption cleaners? Experimental evidence suggests an affirmative answer, showing that females generally are less likely than males to engage in corrupt acts (Alatas et al., 2009; Fisar et al., 2016; Jha & Sarangi, 2018; Lambsdorff & Frank, 2011; Rivas, 2013; for excellent surveys, see Abbink, 2006; Frank et al., 2011; Chaudhuri, 2012; Stensöta & Wängnerud, 2018), and that female voters tend to punish corrupt politicians and their parties more harshly than male voters (Eggers et al., 2018).Footnote 1 In line with those experimental results, several survey-based studies document a stark, negative correlation between being female and corruption levels or tolerance of corruption (Alexander, 2018; Alexander & Bågenholm, 2018; Bauhr & Charron, 2020; Dollar et al., 2001; Esarey & Chirillo, 2013; Esarey & Schwindt-Bayer, 2018; Lee & Guven, 2013; Sundström & Wängnerud, 2016; Swamy et al., 2001; Torgler & Valev, 2010; Vijayalakshmi, 2008).Footnote 2

While the literature suggests a possible gender-corruption link, the mechanisms through which this link evolves remain under-explored. First, prior research has not clearly identified when gender matters, i.e., the specific corruption conditions under which men and women behave differently. Second, previous experiments focus mainly on male-female differences in bribing behavior, i.e., willingness to engage in a corrupt act in the pursuit of private gains. No prior research thus far has explored experimentally gender differences in the tolerance of bribery, i.e., in the evaluation of corrupt acts when one is neither involved in, nor directly affected by them. Nonetheless, that aspect of corruption is important since tolerance of illegal behaviors plays a critical role in the proliferation and persistence of those actions (Alatas et al., 2009; Kubbe & Engelbert, 2018)Footnote 3; and it likely differs across individuals (Alexander, 2018; Alexander et al., 2019; Barr & Serra, 2010; Lee & Guven, 2013). The logic is simple: when individuals are accustomed to corruption and simply treat it as a cost of ordinary business, corruption no is longer a social issue (Banerjee et al., 2021; Chang, 2020; Munger, 2019). General acceptance of corruption likely leads to rent seeking (Choi & Storr, 2019; Lambsdorff, 2002; Tullock, 1980, 1985, 1987, 1988) and a pervasive “transitional gains trap”, wherein it may nearly be impossible to root out corruption (Méon & Sekkat, 2005; Tullock, 1967, 1975, 1996).Footnote 4

In the paper at hand, we explore whether—and under what conditions—males and females differ in their tendencies to act corruptly and in their moral evaluations of corrupt acts. In so doing, we rely on the experimental data reported in Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021), and expand it specifically by exploring gender differences. Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021) is a modified version of Barr and Serra’s (2009) bribery game. That game simulates a simple bribery situation in which a citizen could bribe a public official, who then can accept or reject it. Accepting the bribe yields private gains to both the citizen and the official, but imposes a financial loss on other members of society. The other members of society are idle victims, included in the game to simulate the negative externalities generated by corruption. All other players suffer a (deadweight) loss for every bribe exchanged.

Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021) add two novel aspects to the standard Barr and Serra (2009) bribery game, which also has been played in, e.g., Cameron et al. (2009), Barr and Serra (2010), and Chaudhuri et al. (2016). First, to measure individuals’ tolerance of bribery experimentally, Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021) introduce—for the first time in a bribery game—a fourth player, the monitor, who acts as a third-party punisher and cannot engage in bribery.Footnote 5 More important, the monitor’s payoff is not affected by any corrupt act, but he can react to it by allocating some of his own resources to impose a larger financial cost on the corrupt actor or actors.Footnote 6 That setup—which is known in experimental economics as third-party punishment (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004)—allows us to pinpoint gender differences in corruption precisely.

Monitors can be seen as voters, who can decide to exercise costly effort in casting their votes. Female and male voters may tolerate corrupt actors differently, punishing them by voting for another political party (e.g., Alexander et al., 2019; Chang, 2020; see also Azfar & Nelson, 2007; Arvate & Mittlaender, 2017). Understanding that possibility is crucial for public policies. For instance, if females are found to be more likely to vote against corrupt actors than males, then policies aimed at promoting and encouraging active female participation in elections or other decision-making processes may filter out corrupt actors from governments, bureaucracies, or other social groups concerned with public affairs, such as labor unions and business organizations.

Second, Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021) manipulate two key bribery dimensions experimentally: the private gains of the corrupt actors and the negative externality imposed by corruption on other members of society (either low or high). That same approach allows us to ask whether men and women respond differently to the tradeoff between the benefits versus the external costs of corruption in both bribing behavior and tolerance of bribery (third-party punishment behavior). Larger private gains of the corrupt actors make monitors worse off with respect to corrupt actors, while on the other hand, larger negative externalities raise inequities between the corrupt actors and their idle victims but make monitors better off with respect to the latter. Those differences in the consequences of corruption ultimately affect social welfare overall—either enhancing or reducing it—allowing us to determine how reactions to welfare effects possibly vary by gender.

The distinction between welfare-enhancing and welfare-reducing corruption has received little experimental attention (Abbink et al., 2002; Balafoutas et al., 2021; Cameron et al., 2009), nor has a gender perspective been adopted. We contribute to the experimental literature by exploring whether male and female subjects behave differently depending on the payoff inequities—and, in turn, the welfare effects—generated by corruption.

Good reasons exist to believe that both payoff inequities and overall welfare consequences may affect males and female behavior differently. Indeed, the literature on gender differences in other-regarding preferences (Croson & Gneezy, 2009; Eckel & Grossman, 1998) implies that females engage less frequently in and are less tolerant of corruption than males as the negative externality increases, owing to their stronger senses of fairness and equity (Cox, 2002; Mieth et al., 2017) and being more concerned about others’ welfare (Alexander et al., 2019; Cumming et al., 2015; Eagly et al., 2000). Several studies exploring attitudes towards unethical behaviors—including corruption and tax evasion—provide evidence of females behaving more ethically (being more concerned with the so-called public good than their own) than males (Chaudhuri, 2012; Swamy et al., 2001; Torgler & Valev, 2010). By contrast, males may not object to corruption if it increases their private gains because they are more selfish than females (Andreoni & Vesterlund, 2001; Eckel & Grossman, 1998). Nonetheless, previous studies report mixed results, and present a confusing picture of when and why males and females differ in other-regarding preferences (Croson & Gneezy, 2009). In some experiments, females are more inequity-averse than males, whereas in others they are less so. Hence, while we can expect possible gender differences in response to the experimental treatments, we cannot clearly predict their directions a priori.

Our results show that, on average, no gender difference is observed in bribing behavior. Nonetheless, we find gender differences in the tolerance of bribery, with male monitors punishing corrupt actors less often than female monitors, but to a greater extent. Our treatment manipulations show that looking at averages does not reveal the entire story. Gender gaps in bribery depend strongly on both the exact contextual conditions and the role taken in the bribery act. Our results reveal that females engage less in, and are less tolerant of bribery when its negative externality increases, reducing welfare overall. Males punish corrupt actors more severely when the gains to corrupt actors increase, yielding them a comparative payoff disadvantage with respect to the latter. Regarding the part played in bribery acts, our findings reveal consistent behavior by females across roles, as a response to a larger externality that reduces welfare overall. Apart from that, gender behavior is strongly role-dependent.

Our research adds important insights to the literature, which hitherto has established the conventional wisdom about gender differences in corruption (Chaudhuri, 2012; Stensöta & Wängnerud, 2018), and—more broadly—dishonesty (Abeler et al., 2016, 2019). Prior contributions generally have suggested that females behave as corruption cleaners because of their more critical attitudes to corruption, albeit without specifying the exact contextual factors under which those divergences with males may arise. The main takeaway message of our paper is that either males or females can be found to be more prone to bribe or more tolerant of corruption, depending on both the payoff differentials generated by corruption and the role played in the bribery act. In a broader perspective, our research suggests that gender behavior is context- and role-dependent, and cannot be characterized simply.

The remainder of the paper at hand proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents the experimental design and procedure. Section 3 reports the results. Section 4 discusses the main findings and concludes.

2 Experimental design

2.1 The bribery game

In this section, we briefly describe the experimental design of Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021), to which we refer for more details. The game is similar to Barr and Serra (2009) and mimics a collusive bribery situation. At the beginning of the experiment, players are matched randomly and anonymously to eight groups of four players. In each group, subjects are assigned randomly to one of the following roles: a citizen, a public official, another member of society, and a monitor. The roles remain fixed throughout the experiment.

The design comprises a four-person, sequential-move game. The first player is the citizen, who is given the option to offer a bribe to the official. The official is the second player, who can either reject or accept the bribe. If the bribe is accepted, both the citizen and the official are better off financially at the expense of idle corruption victims, to whom we refer as other members of society. The latter cannot respond to the corrupt act, and their final payoffs depend exclusively on the overall number of bribes exchanged: all other members suffer a financial loss for every bribe exchanged among the eight citizen-official pairs.Footnote 7 The last player is the monitor, who acts as a third-party impartial bystander: he/she observes the citizen’s and official’s choices in his group, but his/her payoff is not affected by any corrupt act. Within each group, the monitor is given the option of punishing either the citizen, the official, or both. Punishment of bribery is costly for the monitor and it imposes a larger financial loss on the citizen and the official. The punishment cost may represent, e.g., the cost of filing a police report, appearing in court, or casting a vote against corrupt politicians (Alatas et al., 2009). The Nash equilibrium of the game (for selfish preferences) is for the monitor not to punish because punishment is costly to him/her. Anticipating the monitor’s behavior, the official always will accept the bribe and the citizen always will offer it. This rational actor model applies equally to males and females.

The parameters of the game are expressed in tokens (one token = 0.20 Euro), and set as follows. Each player receives an initial endowment of 50 tokens. In each group, the citizen can offer a bribe of three tokens to the official. If the official accepts the bribe, the citizen’s and the official’s payoffs increase each by 3α, where α > 1,Footnote 8 and the citizen’s payoff declines by the bribe amount. If the official rejects the bribe, it returns to the citizen. All other members incur a cost of 3γ, with γ ≥ 1, for every bribe exchanged among the eight citizen-official pairs. The monitor—who moves last after observing the choices made by the citizen and the official in his/her group—is given the option of allocating money from his/her endowment, pC ∈ [0, 10] to punish the citizen and pO ∈ [0, 10] to punish the official. The punishment is costly to the monitor—whose payoff is reduced by the punishment amount—and imposes a larger financial loss on the citizen and/or the official, whose payoffs are reduced by twice the punishment amount.

Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021) adopt a 2 × 2 between-subject design (Fig. 1) to vary the size of private gains, α—by setting them either low at αL = 3, or high at αH = 6—and the size of the negative externality, γ, by setting it either low at γL = 1 or high at γH = 2.

Those treatments generate payoff inequities between the players’ roles and, in turn, welfare outcomes. Specifically, in terms of payoff differentials, (i) holding negative externality constant, larger benefits make monitors worse off with respect to corrupt actors (nine tokens fewer with respect to each corrupt actor’s payoff), while their relative payoff with respect to the other players does not change; and (ii) holding benefits constant, larger externalities do not change monitors’ relative payoff with respect to corrupt actors, but make them better off with respect to the other players (from a minimum of three tokens more with respect to each victim’s payoff if one bribe overall was exchanged in a round, to a maximum of 24 tokens more if eight bribes overall were exchanged).

In terms of welfare overall, in the “Low Externality High Benefits” treatment, bribery is welfare-enhancing: the total benefits (equal to 36, because the citizen and official both gain 18) exceed the total external cost (equal to 24, because the other players suffer a loss of three each). In the other treatments, bribery is welfare-reducing. More important, increasing the externality under high benefits turns welfare-enhancing bribes into welfare-reducing ones, whereas the opposite occurs when increasing the benefits under low externality. Here—unlike in Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021)—we rely on treatment manipulations to uncover male and female reactions to different payoff inequities and welfare outcomes.

Figure 2 contains an extensive-form representation of the game with players’ final payoffs, which are computed as follows. The citizen’s final payoff is 50 if he does not offer a bribe; 47 + 3α if he offers a bribe that is accepted, minus 2pC if he is punished; and 50 if he offers a bribe that is rejected, minus 2pC if he is punished. The official’s final payoff is 50 if he is not offered a bribe; 50 if he is offered a bribe but rejects it, minus 2pO if he is punished; and 53 + 3α if he accepts a bribe, minus 2pO if he is punished. Let n ∈ {0, …, 8} be the total number of bribes exchanged in one round among all eight citizen-official pairs. The other member of society’s final payoff equals 50—3nγ: it ranges between 50 (no bribes exchanged at all) and 50—24γ (bribes exchanged in all eight citizen-official pairs); it can reach a minimum of 2 if γ = 2. The monitor’s final payoff equals 50 if he/she does not punish, minus pC ∈ [0, 10] and pO ∈ [0, 10] if he/she punishes, ranging between 30 and 50. For a better understanding of the game, Fig. A1 in the Online Appendix A presents an example of the outcomes and payoffs under the “High Externality High Benefits” treatment if the monitor spends ten tokens to punish each corrupt actor in his/her group (if a bribe was exchanged), assuming that bribes have been exchanged in the other seven citizen-official pairs.

The structure of the experiment. Notes: 50 is the initial endowment; three is the bribe amount; pC and pO are the amounts chosen by the monitor to punish the citizen and the public official, respectively; \(n \in [0,\dots , 8]\) is the total number of bribes exchanged in a round among all the eight citizen-official pairs, with \(\underline{n}\) \(\in [0,\dots , 7]\) and \(\overline{n }\) \(\in [1,\dots , 8]\); \(\alpha \in \{3, 6\}\) and \(\gamma \in \{1, 2\}\) reflect the treatments (benefits and externality, respectively)

The bribery game comprises ten identical and independent rounds, with players being re-matched randomly to different groups from one round to the next. To avoid issues associated with repeated games—e.g., learning, conditional cooperation—no feedback between rounds is provided about monitors’ choices, nor the choices of other players in the other groups. The setup preserves the essence of one-shot interactions (Alatas et al., 2009), while avoiding repeated-game effects (Chaudhuri et al., 2016).

At the end of experiment, all subjects are asked some questions about their personal characteristics. We enter that information in our regression analyses as a robustness check. Specifically, our control variables include Age, measured in years; Education, measured as a dummy equal to one for university degree, and zero for high school degree; Field of Study, measured as a categorical variable including Engineering and Architecture, Arts and Humanities, and Other; and Risk Aversion, measured as an individual’s self-assessment of risk attitudes over a ten-point scale, where one means “not at all prepared to take risks” and ten “very strongly prepared to take risks”.Footnote 9 Controlling for risk aversion is important here since prior experiments show that gender differences in corrupt behaviors likely are driven by females’ stronger risk aversion (Rivas, 2013; Schulze & Franck, 2003).

2.2 Procedures

Data were collected in eight sessions (two per treatment) at the Bologna Laboratory for Experiments in Social Science (BLESS) at the University of Bologna (Italy) in May 2019. Each session lasted approximately 70 minutes in total. The order of sessions was randomized to control for possible session-time effects (Fréchette, 2012). A total of 256 players (64 per treatment) were recruited via ORSEE (Greiner, 2015), of which 132 were male (124 female).Footnote 10 To rule out any cultural bias (Alatas et al., 2009; Del Monte & Papagni, 2007; Treisman, 2000), participation in the experiment was restricted to Italian citizens born in the North of Italy to Italian parents.

The experiment was designed using oTree (Chen et al., 2016), and subjects performed all tasks on computers. The instructions—available in the Online Appendix A—were handed out to the players, and read aloud by the experimenter. Before starting the experiment, the players were asked to answer a computer-based quiz containing eight comprehension questions, and they were given direct feedback in response to incorrect answers. At the end of the experiment, the computer chose one round randomly for subject payment. Subjects were paid anonymously in cash after each session, with an average payment of 14.56 Euros (including a show-up fee of 5 Euros).

3 Results

In this section, we evaluate gender differences in bribing behavior (Sect. 3.1), and tolerance of bribery (Sect. 3.2). In the Online Appendix A, we report the number of subjects per treatment, the role played, and sex (Table A1); the summary statistics of the variables of interest (Table A2), including the confidence intervals and numbers of observations per treatment and gender; the summary statistics of demographic variables for the full sample (Table A3), showing that the sample is balanced across treatments and roles across individual demographics (Sect. A.2); and other robustness checks (Sect. A.4).

Following similar small-sample studies (e.g., Abbink et al., 2001; Schram et al., 2019), we show that our observations allow for valid inferences when applying appropriate statistical methods, which we discuss here.Footnote 11 Similar to Moir (1998), Abbink et al. (2001) and Schram et al. (2019), in all of our statistical tests we calculate permutation t tests and permutation χ2 tests using Monte-Carlo resampling with 5000 repetitions (henceforth, Pt and Pχ2, respectively).Footnote 12 Following Abbink et al. (2001), the permutation tests are applied to session averages (across the ten rounds).Footnote 13 To deal with potential within-group and serial correlation, in our econometrics analyses standard errors (henceforth, SE) are two-way clustered at the group and round level (Cameron & Miller, 2015; de Chaisemartin & Ramirez-Cuellar, 2020), and bootstrapped with 1000 replications to deal with small samples (Cameron et al., 2008). Our regression results are robust to controls for individual characteristics, start- and end-game effects (Gonzalez et al., 2005), and alternative regression specifications, including double-hurdle regression models for punishment behavior (Chaudhuri et al., 2016; Cragg, 1971).Footnote 14

3.1 Gender differences in bribing behavior

In this section, we investigate whether varying the sizes of benefits and externalities differently affects male and female tendencies to exchange bribes. By pooling observations across treatments, our data reveal no significant gender difference in bribing behavior, neither in the frequency of bribe offers (50.29% for females versus 54.00% for males; Pχ2: p > 0.10; Obs. = 340 for females, Obs. = 300 for males), nor bribe acceptance (73.39% for females versus 68.42% for males; Pχ2: p > 0.10; Obs. = 124 for females, Obs. = 209 for males). Instead, significant gender differences emerge when analyzing behavior by treatments.

Figure 3 displays the fractions of males (white bars) and females (gray bars) offering a bribe (graphs on the left) and accepting a bribe (graphs on the right), for each treatment—i.e., externality (graphs at the top) and benefits (graphs at the bottom)—while holding the other constant (i.e., either ‘high’ or ‘low’). Males and females react to externality in opposite ways. Increasing externality under high benefits causes females to reduce the frequency of both bribe offers (from 72.00 to 38.57%; Pχ2: p < 0.001; Obs. = 170) and bribe acceptance (from 96.97 to 15.79%; Pχ2: p < 0.001; Obs. = 52), whereas it prompts males to increase the frequency of bribe offers and acceptances, with only the latter effect being statistically significant (from 71.43 to 89.66%; Pχ2: p < 0.05; Obs. = 128). On the other hand, increasing externality under low benefits reduces the percentage of males offering bribes (from 66.67 to 45.56%; Pχ2: p < 0.05; Obs. = 150), whereas it increases the percentage of females accepting bribes (from 68.29 to 90.32%; Pχ2: p < 0.10; Obs. = 72). Increasing benefits under low externality induces females to increase the frequencies of both bribe offers (from 47.00 to 72.00%; Pχ2: p < 0.001; Obs. = 200) and acceptance (from 68.29 to 96.97%; Pχ2: p < 0.05; Obs. = 74). Increasing the benefits of corruption does not change the frequency of males offering bribes, neither under low nor high externality, although it changes the frequency of males accepting a bribe under high externality (from 42.86 to 89.66%; Pχ2: p < 0.05; Obs. = 93).

Gender differences in bribing behavior by treatment. Notes: Average frequency of bribe offers and acceptance, by treatment and gender. Bribe Offer equals 1 if a citizen decides to offer a bribe; Bribe Acceptance equals 1 if an official decides to accept a bribe. For detailed summary statistics, see Table A2 in Online Appendix A

The descriptive statistics are confirmed by regression analysis. Table 1 reports the marginal estimates from Probit regressions, wherein we consider two different dummies as dependent variables separately: Bribe Offer, is one if a citizen decides to offer a bribe (Cols 1–2); and Bribe Acceptance, is one if an official decides to accept a bribe (Cols 3–4). Independent variables include treatment dummies, with the ‘Low Ben. Low Ext.’ treatment being the reference category; the gender dummy Female; the interaction between each treatment dummy and Female. Regression models in Cols 2 and 4 include a number of individual-level controls and their interaction with Female. The estimates reveal significant gender differences in response to higher externality under high benefits, wherein females are significantly less likely to engage in bribery than males. In contrast, increasing benefits under low externality prompts females to be more likely to offer bribes than males. In all other cases, gender differences are not statistically or consistently significant. The results are robust to individual-level controls (Cols 2 and 4 in Tables 1 and A4).

3.2 Gender differences in tolerance of bribery

We now ask whether varying the sizes of benefits and externality differently affects male and female tendencies to punish corrupt actors when they are assigned to the role of monitor. Following Carpenter and Matthews (2009) and Chaudhuri et al. (2016), we consider two dimensions of punishment: the decision to punish, i.e., the fraction of monitors who decide to punish corrupt actors, given that a bribe has been offered; and the decision of how much to punish, i.e., the amount spent by monitors on punishment, conditional on their decision to punish. In doing so, we consider two separate, yet interrelated variables: Punishment Frequency, which is a dummy equal to one if a monitor decides to punish corrupt actors (either the citizen and/or the official) within the group; and Punishment Size, which is a discrete variable ranging from one to ten, conditional on Punishment Frequency being equal to one. We analyze punishment of citizens (given that a bribe has been offered), and officials (given that a bribe has been accepted) separately.

First, we consider data pooled across treatments to detect average male-female differences in punishment behavior. Figure 4 presents punishment frequency (graphs at the top) and size (graphs at the bottom) of citizens (graphs on the left) and officials (graphs on the right), separately for males (white bars) and females (gray bars). On average, females punish corrupt citizens statistically more often than males (58.29% versus 48.10%; Pχ2: p < 0.10; Obs. = 175 for females, Obs. = 158 for males), as well as officials (58.06% versus 49.09%; Pχ2: p > 0.10; Obs. = 124 for females, Obs. = 110 for males), although the latter difference is not statistically significant. However, females punish to a lesser extent than males.Footnote 15 Specifically, male monitors allocate on average 6.18 tokens versus 4.27 tokens by females to punish citizens (Pt Welch’s formula: p < 0.001; Obs. = 102 for females, Obs. = 76 for males) and 6.93 tokens versus 4.86 tokens allocated by females to punish officials (Pt Welch’s formula: p < 0.001; Obs. = 72 for females, Obs. = 54 for males).

Gender differences in punishment frequency and size. Notes: Average punishment frequency and size towards citizens and officials, by gender. Data pooled across treatments. Punishment Frequency equals one for punishment, zero otherwise; Punishment Size ranges between one and ten, and represents the punishment amount, given the decision to punish. For detailed summary statistics, see Table A2 in Online Appendix A

Next, we estimate a series of regressions to ask whether male and female monitors respond differently to treatment variations. Table 2 reports the regression results. Panel A displays the estimates of Probit marginal effects for the dummy Punishment Frequency (=1 for punishment); Panel B reports estimates of linear regression models for Punishment Size (ranging between one and ten).Footnote 16 We distinguish between the punishment of citizens given that a bribe has been offered (Cols 1–2) and the punishment of officials given that a bribe has been accepted (Cols 3–4). Independent variables are treatment dummies, with the ‘Low Ben. Low Ext.’ treatment being the reference category; the gender dummy Female; and interactions between each treatment dummy and Female. The regression models in Cols 2 and 4 include individual-level controls and their interactions with Female.

The regression estimates reveal significant gender differences in punishment behavior as reactions to treatments, but only in the actual size of punishment, not its frequency. Increasing the benefits of bribery under low externality leads females to punish corrupt actors to a lesser extent than males do. On the other hand, increasing external costs with high bribery benefits leads female monitors to punish corrupt actors more severely than males do. The results are robust to entering individual-level controls (Cols 2 and 4 in Tables 2 and A6).

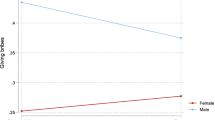

The findings above are clearly shown in Fig. 5, which reports the average punishment size by treatment and gender. Fig. 5 generally shows that male and female reactions to larger benefits (graphs at the bottom) proceed in the opposite direction with respect to their reaction to larger external costs of bribery (graphs at the top). Consistent with the regression estimates, the graphs reveal substantial gender differences in welfare-shifting bribes. Specifically, males reduce their punishment expenditures with increasing externality in the presence of high benefits: from 8.19 to 5.95 tokens to punish citizens, and from 8.29 to 7.00 tokens to punish officials. By contrast, females increase their punishment expenditure with increasing externality in the face of high benefits: from 3.63 to 5.82 tokens to punish citizens, and from 4.61 to 5.37 tokens to punish officials. On the other hand, male and female reactions to larger benefits mostly go in the opposite direction. For instance, when increasing benefits with low externalities, males increase their punishment of bribe-offering citizens from 4.11 to 8.19 tokens, and of corrupt officials from 4.69 to 8.29 tokens, whereas females reduce their punishment from 3.83 to 3.63 tokens of citizens, and from 5.23 to 4.61 tokens of officials.

Gender differences in punishment size by treatment. Notes: Average punishment size towards citizens and officials, by treatment and gender. Punishment Size ranges between one and ten, and represents the punishment amount, given the decision to punish. For detailed summary statistics, see Table A2 in Online Appendix A

4 Discussion and conclusion

Do women behave as corruption cleaners? While a wide variety of experimental studies would suggest a qualified yes, our results propose a more nuanced answer. Neither males nor females are uniformly more prone to offer bribes or to tolerate corruption: it depends on the precise bribery environment (low/high benefits versus low/high external costs), and the part played in the bribery act (e.g., as a citizen, official, monitor, or idle victim). We find no gender differences in bribing behavior overall. Nonetheless, we do find gender differences in the tolerance of bribery: on average, when not involved in bribery directly, males punish corrupt actors less often than females do, but punish more severely. From a theoretical perspective, that result reveals inconsistencies between behavior (engagement in bribery) and attitudes (tolerance of bribery), as measured by the punishment of corrupt actors; caution thus is warranted when interpreting attitudinal responses to corruption. From a policy perspective, our findings suggest that a balanced mix of males and females in governmental and business workplaces is likely to raise both punishment frequency (mainly driven by females) and severity (mainly driven by males). Mandating the representation of females as political leaders or policymakers—e.g., affirmative-action policies increasingly implemented at various levels of government (in India: Chattopadhyay & Duflo, 2004; Mexico: Anozie et al., 2004; Chaudhuri, 2012; Goetz, 2007)—could favor punishment’s frequency over its size.

However, looking at averages does not reveal the entire story and can be misleading. By manipulating the key bribery dimensions experimentally, we find that neither males nor females are uniformly more likely to engage in, or be more tolerant of corruption. Instead, differences in male-female behavior are treatment and role-specific, with males and females behaving differently depending on the tradeoff between the benefits gained by corrupt actors versus the negative externality generated by bribery on other people. When corruption reduces welfare overall, females are less likely to engage in and tolerate it. However, if the externalities are low, increasing the benefits of corruption makes females more likely to offer bribes, and to punish corrupt actors less severely than males. More specifically, males punish corrupt actors more severely than females when the combined gains to corrupt actors exceed the losses to society, imposing on them a comparative payoff disadvantage with respect to corrupt actors.

Our results add important and novel insights to the literature on gender differences in bribery—and, more broadly, dishonesty—which thus far has generalized male and female behavioral gaps instead of specifying the exact contextual factors under which those gaps may arise. More pro-female policies might reduce corruption in some circumstances, but might backfire in others. Policies aimed simply at increasing female participation in the public sector or as policymakers at various levels of government—e.g., affirmative-action policies such as those implemented in India (Chattopadhyay & Duflo, 2004), Mexico City (Chaudhuri, 2012; Goetz, 2007), Argentina (Jones, 1998), and the United Kingdom (Norris, 2001)—may not necessarily reduce corruption, since varying bribery dimensions change its welfare effects, and those effects likely drive males’ and females’ aversive reactions to bribery.Footnote 17

While our findings by themselves do not reveal the reasons why males and females react to treatments differently, we can provide different interpretations by comparing our experimental findings to the broadly defined gender literature. The notion that females become less prone to and less tolerant of corruption when it yields negative welfare effects is consistent with experimental evidence showing that females are more concerned about fairness and equity (Cox, 2002; Eckel & Grossman, 1998, 2008). The notion that male monitors punish corrupt actors more severely when the latter gain larger benefits is consistent with the experimental evidence that males are more self-centered money maximizers, and that they care more about their comparative payoff disadvantage than welfare overall (Andreoni & Vesterlund, 2001; Dreber & Johannesson, 2008; Gneezy et al., 2003; Schram et al., 2019).

However, the lessons to be learned from our paper extend beyond mere support for evidence that females are more prosocial than males, and that males are more self-centered and inequity-averse (Fehr & Schmidt, 1999). Indeed, when zooming out and looking at all results together, one might recognize that male and female differences in bribery not only depend on the exact bribery conditions but also on the roles that individuals play in corrupt transactions. A notable exception is the consistent response of females to welfare-reducing bribes across all possible roles. Apart from that, male and female behavior is strongly role-dependent. For instance, when benefits increase under low externality, males and females do not significantly differ in their bribe acceptance behavior, but they differ in their punishment choices, wherein female monitors punish officials less severely than males. Instead of appearing puzzling, those results reinforce the main takeaway message of our paper: depending on the payoff differentials generated by corruption—and, in turn, on different welfare considerations—as well as the actor’s role in the bribery act, either males or females can be found to be more prone to or tolerant of corruption. From a broader perspective, our research suggests that male and female behavior is context- and role-dependent, and cannot be generalized in simple terms.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

On other mechanisms explaining the persistence of corruption, see, e.g., Damania et al. (2004).

Gordon Tullock was a pathbreaking scholar in the field. For reviews of his works, see, e.g., Mueller (2012), Parisi et al. (2017), and the special issues published in Public Choice by Rowley and Houser (2012) and Mitchell (2019). We thank Associate Editor Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard for this suggestion.

Other experiments have relied on monitors—also referred to as spectators, bystanders, or third parties—to assess attitudes towards, e.g., altruism, fairness, inequity aversion (e.g., Carpenter & Matthews, 2009; Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004). However, to our knowledge, only two studies thus far have explored gender differences in other third-party punishment games: Kromer and Bahçekapili (2010) and Mieth et al. (2017). The results are mixed. Kromer and Bahçekapili (2010) conduct an ultimatum game and find that third-party males are more willing than females to punish unfair offers made by dictators. Mieth et al. (2017) run a prisoner’s dilemma game, finding the opposite result.

The setup follows Barr and Serra (2009), differing from Cameron et al. (2009), wherein corruption victims also are the punishers (second-party punishment) and only one player is affected by the bribe exchanged within the group. Guerra and Zhuravleva (2021) follow Barr and Serra (2009) to mimic real-world cases wherein bribery harms many individuals and not only one, as in Cameron et al. (2009).

The assumption follows from Abbink et al. (2002), Abbink and Hennig-Schmidt (2006), and Alatas et al. (2009), wherein the bribe amount is tripled before being passed on to the official. The rationale is to ensure mutual gains from bribery for corrupt actors, while avoiding excessively unequal payoffs.

No comparable published data were/are available to support sample size determination, nor power calculations, neither ex-ante nor ex-post. Moreover, conducting ex-post power analysis for experimental data involving multiple repetitions entails technical problems that likely lead to misleading results. On power analyses, see, e.g., Nikiforakis and Slonim (2015); for a critical appraisal on ex-post design calculations, see, e.g., Gelman and Carlin (2014). Our sample size of 256 players is comparable to other, related bribery experiments (see, e.g., Barr et al., 2009; Barr & Serra, 2009, with 144 and 195 subjects, respectively; Rivas, 2013; Serra, 2012; Chaudhuri et al., 2016, with 102, 180, and 210 subjects, respectively). Future researchers are welcome to use our current data for sample determination and other power analysis.

We acknowledge that when sample sizes are small, one might be less confident in the validity of the results, regardless of the procedures for computing significance levels (e.g., Maniadis et al., 2014). Here, we implement statistical techniques validated in similar small-sample studies (e.g., Abbink et al., 2001; Schram et al., 2019). A larger sample size and additional future research would aid in supporting the accuracy of our results. We thank two anonymous referees for thoughtful comments on that matter.

Permutation (a.k.a. randomization) tests (Fisher 1935) are based on reshuffling treatment labels in a dataset, do not make any assumptions about the underlying distributions, and have been adopted in small-sample studies since the number of observations needed for trustworthy inferences is much less than for the tests more common in experimental work (e.g., Abbink et al., 2001; Davis & Holt, 1993, pp. 542–544; Moir, 1998; Schram et al., 2019). For instance, Moir (1998), Abbink et al. (2001), and Schram et al. (2019) demonstrate the validity of permutation tests with eight, ten, and 16 observations per treatment cell. In our statistical analyses, the number of observations (across the ten rounds) per treatment cell varies between 40 and 350, allowing for valid inferences with permutation tests.

As a robustness check, coherently with the regression analysis we have stratified permutation tests at the group and round level. The main results are robust to this stratification and available upon request. We thank an anonymous reviewer for useful comments on this point.

Robustness checks are reported in Section A.4 in the Online Appendix A.

The result matches with Alatas et al. (2009), where female (second-party) punishers spend less on punishing corrupt actors than males.

The results hold when estimations are obtained simultaneously—rather than one regression at a time—by applying Cragg’s (1971) two-tier (a.k.a. double-hurdle) model, i.e., a generalization of the Tobit model for corner-solution models. See Online Appendix A.

Reserving quotas for female participation in policymaking have been shown to have strong effects on policy decisions and outcomes (Chattopadhyay & Duflo, 2004), e.g., on public goods spending, average competence in the candidates’ pool, and voter preferences for political parties. See also Lott and Kenny (1999), showing that males and females have different policy preferences; extending the franchise to US women moved public policies leftward on the political spectrum. None of those contributions has called into question gender differences in the laboratory. We are grateful to the Editor in Chief William F. Shughart II and an anonymous referee for pointing us to that literature.

References

Abbink, K. (2006). Laboratory experiments on corruption. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), International handbook on the economics of corruption (pp. 418–437). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Abbink, K., Bolton, G. E., Sadrieh, A., & Tang, F.-F. (2001). Adaptive learning versus punishment in ultimatum bargaining. Games and Economic Behavior, 37(1), 1–25.

Abbink, K., & Hennig-Schmidt, H. (2006). Neutral versus loaded instructions in a bribery experiment. Experimental Economics, 9(2), 103–121.

Abbink, K., Irlenbusch, B., & Renner, E. (2002). An experimental bribery game. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 18(2), 428–454.

Abeler, J., Nosenzo, D., and Raymond, C. (2016). Preferences for truth-telling. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) (10188).

Abeler, J., Nosenzo, D., & Raymond, C. (2019). Preferences for truth-telling. Econometrica, 87(4), 1115–1153.

Alatas, V., Cameron, L., Chaudhuri, A., Erkal, N., & Gangadharan, L. (2009). Gender, culture, and corruption: Insights from an experimental analysis. Southern Economic Journal, 75(3), 663–680.

Alexander, A. C. (2018). Micro-perspectives on the gender-corruption link. In I. Kubbe & A. Engelbert (Eds.), Corruption and norms: Why informal rules matter (pp. 53–68). Springer.

Alexander, A. C., & Bågenholm, A. (2018). Does gender matter? Female politicians’ engagement in anti-corruption efforts. In H. Stensöta & L. Wängnerud (Eds.), Gender and corruption (pp. 171–189). Springer.

Alexander, A. C., Bågenholm, A., & Charron, N. (2019). Are women more likely to throw the rascals out? The mobilizing effect of social service spending on female voters. Public Choice, 184(3), 235–261.

Andreoni, J., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 293–312.

Anozie, V., Shinn, J., Skarlatos, K., and Urzua, J. (2004). Reducing incentives for corruption in the Mexico City Police Force. In International Workshop, Public Affairs (pp. 869). Retrieved from https://www.lafollette.wisc.edu/images/publications/workshops/2004-MEXICO.pdf

Arvate, P., & Mittlaender, S. (2017). Condemning corruption while condoning inefficiency: An experimental investigation into voting behavior. Public Choice, 172(3), 399–419.

Azfar, O., & Nelson, W. R. (2007). Transparency, wages, and the separation of powers: An experimental analysis of corruption. Public Choice, 130(3–4), 471–493.

Balafoutas, L., Sandakov, F., & Zhuravleva, T. (2021). No moral wiggle room in an experimental corruption game. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.701294/full

Banerjee, R., Boly, A., & Gillanders, R. (2021). Is corruption distasteful or just another cost of doing business? Public Choice. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3570758

Barr, A., Lindelow, M., & Serneels, P. (2009). Corruption in public service delivery: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 72(1), 225–239.

Barr, A., & Serra, D. (2009). The effects of externalities and framing on bribery in a petty corruption experiment. Experimental Economics, 12(4), 488–503.

Barr, A., & Serra, D. (2010). Corruption and culture: An experimental analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 94(11–12), 862–869.

Bauhr, M., & Charron, N. (2020). Do men and women perceive corruption differently? Gender differences in perception of need and greed corruption. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 92–102.

Burke, W. J. (2009). Fitting and interpreting Cragg’s tobit alternative using Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(4), 584–592.

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2008). Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 414–427.

Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. L. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372.

Cameron, L., Chaudhuri, A., Nisvan, E., & Gangadharan, L. (2009). Propensities to engage in and punish corrupt behavior: Experimental evidence from Australia, India, Indonesia and Singapore. Journal of Public Economics, 93(8), 843–851.

Carpenter, J., & Matthews, P. H. (2009). What norms trigger punishment? Experimental Economics, 12(3), 272–288.

Chang, E. C. (2020). Corruption predictability and corruption voting in Asian democracies. Public Choice, 184(3), 307–326.

Chang, E. C., & Kerr, N. N. (2017). An insider–outsider theory of popular tolerance for corrupt politicians. Governance, 30(1), 67–84.

Chattopadhyay, R., & Duflo, E. (2004). Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica, 72(5), 1409–1443.

Chaudhuri, A. (2012). Gender and corruption: A survey of the experimental evidence. In D. Serra & L. Wantchekon (Eds.), New advances in experimental research on corruption, Chapter 2 (Vol. 15, pp. 13–49). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Chaudhuri, A., Paichayontvijit, T., & Sbai, E. (2016). The role of framing, inequity and history in a corruption game: Some experimental evidence. Games, 7(2), 13.

Chen, D. L., Schonger, M., & Wickens, C. (2016). oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 9, 88–97.

Choi, S. G., & Storr, V. H. (2019). A culture of rent seeking. Public Choice, 181(1), 101–126.

Cox, J. C. (2002). Trust, reciprocity, and other-regarding preferences: Groups vs. individuals and males vs. females. In R. Zwick & A. Rapoport (Eds.), Experimental Business Research (pp. 331–350). Springer.

Cragg, J. G. (1971). Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica, 39(5), 829–844.

Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474.

Cumming, D., Leung, T. Y., & Rui, O. (2015). Gender diversity and securities fraud. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1572–1593.

Damania, R., Fredriksson, P. G., & Mani, M. (2004). The persistence of corruption and regulatory compliance failures: Theory and evidence. Public Choice, 121(3), 363–390.

Datta Gupta, N., Poulsen, A., & Villeval, M. C. (2013). Gender matching and competitiveness: Experimental evidence. Economic Inquiry, 51(1), 816–835.

Davis, D. D., & Holt, C. A. (1993). Experimental economics. Princeton University Press.

de Chaisemartin, C., & Ramirez-Cuellar, J. (2020). At what level should one cluster standard errors in paired experiments, and in stratified experiments with small strata? NBER Working Paper No. 27609.

Del Monte, A., & Papagni, E. (2007). The determinants of corruption in Italy: Regional panel data analysis. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 379–396.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550.

Dollar, D., Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2001). Are women really the fairer sex? Corruption and women in government. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 46(4), 423–429.

Dreber, A., & Johannesson, M. (2008). Gender differences in deception. Economics Letters, 99(1), 197–199.

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Diekman, A. B. (2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In T. Eckes & H. M. Trautner (Eds.), The developmental social psychology of gender. (Vol. 12). Erlbaum.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (1998). Are women less selfish than men?: Evidence from dictator experiments. The Economic Journal, 108(448), 726–735.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Differences in the economic decisions of men and women: Experimental evidence. In C. R. Plott & V. L. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of experimental economics results, Chapter 57 (Vol. 1, pp. 509–519). Elsevier.

Eggers, A. C., Vivyan, N., & Wagner, M. (2018). Corruption, accountability, and gender: Do female politicians face higher standards in public life? The Journal of Politics, 80(1), 321–326.

Esarey, J., & Chirillo, G. (2013). Fairer sex or purity myth? Corruption, gender, and institutional context. Politics & Gender, 9(4), 361–389.

Esarey, J., & Schwindt-Bayer, L. (2018). Women’s representation, accountability and corruption in democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 48(3), 659–690.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25(2), 63–88.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Fisar, M., Kubak, M., Spalek, J., & Tremewan, J. (2016). Gender differences in beliefs and actions in a framed corruption experiment. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 63, 69–82.

Fisher, R. (1935). Design of experiments. Oliver & Boyd.

Frank, B., Lambsdorff, J. G., & Boehm, F. (2011). Gender and corruption: Lessons from laboratory corruption experiments. The European Journal of Development Research, 23(1), 59–71.

Fréchette, G. R. (2012). Session-effects in the laboratory. Experimental Economics, 15(3), 485–498.

Gelman, A., & Carlin, J. (2014). Beyond power calculations: Assessing type s (sign) and type m (magnitude) errors. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(6), 641–651.

Gneezy, U., Niederle, M., & Rustichini, A. (2003). Performance in competitive environments: Gender differences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 1049–1074.

Goetz, A. M. (2007). Political cleaners: Women as the new anti-corruption force? Development and Change, 38(1), 87–105.

Gonzalez, L. G., Güth, W., & Levati, M. V. (2005). When does the game end? Public goods experiments with non-definite and non-commonly known time horizons. Economics Letters, 88(2), 221–226.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 114–125.

Guerra, A., & Harrington, B. (2018). Attitude–behavior consistency in tax compliance: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 156, 184–205.

Guerra, A., & Zhuravleva, T. (2021). Do bystanders react to bribery? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 185, 442–462.

Heidenheimer, A. J. (2002). Perspectives on the perception of corruption. In A. J. Heidenheimer & M. Johnston (Eds.), Political corruption: Concepts and contexts (Vol. 3, pp. 141–154). Transaction Publishers.

Jha, C. K., & Sarangi, S. (2018). Women and corruption: What positions must they hold to make a difference? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 151, 219–233.

Jones, M. P. (1998). Gender quotas, electoral laws, and the election of women: Lessons from the Argentine provinces. Comparative Political Studies, 31(1), 3–21.

Kromer, E., & Bahçekapili, H. G. (2010). The influence of cooperative environment and gender on economic decisions in a third party punishment game. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 250–254.

Kubbe, I., & Engelbert, A. (2018). Corruption and norms: why informal rules matter. Springer.

Lambsdorff, J. G. (2002). Corruption and rent-seeking. Public Choice, 113(1), 97–125.

Lambsdorff, J. G., & Frank, B. (2011). Corrupt reciprocity—Experimental evidence on a men’s game. International Review of Law and Economics, 31(2), 116–125.

Lee, W.-S., & Guven, C. (2013). Engaging in corruption: The influence of cultural values and contagion effects at the microlevel. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39, 287–300.

Lott, J. R., Jr., & Kenny, L. W. (1999). Did women’s suffrage change the size and scope of government? Journal of Political Economy, 107(6), 1163–1198.

Maniadis, Z., Tufano, F., & List, J. A. (2014). One swallow doesn’t make a summer: New evidence on anchoring effects. American Economic Review, 104(1), 277–290.

Méon, P.-G., & Sekkat, K. (2005). Does corruption grease or sand the wheels of growth? Public Choice, 122(1), 69–97.

Mieth, L., Buchner, A., & Bell, R. (2017). Effects of gender on costly punishment. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 30(4), 899–912.

Mitchell, M. D. (2019). Rent seeking at 52: An introduction to a special issue of Public Choice. Public Choice, 181(1), 1–4.

Moir, R. (1998). A Monte Carlo analysis of the Fisher randomization technique: Reviving randomization for experimental economists. Experimental Economics, 1(1), 87–100.

Mueller, D. C. (2012). Gordon Tullock and public choice. Public Choice, 152(1–2), 47–60.

Munger, M. C. (2019). Tullock and the welfare costs of corruption: There is a “Political Coase Theorem.” Public Choice, 181(1), 83–100.

Nikiforakis, N., & Slonim, R. (2015). Editors’ preface: Statistics, replications and null results. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1, 127–131.

Norris, P. (2001). Breaking the barriers: Positive discrimination policies for women. In C. S. Maier & J. Klausen (Eds.), Has liberalism failed women? (pp. 89–110). St Martins Press.

Parisi, F., Luppi, B., & Guerra, A. (2017). Gordon Tullock and the Virginia School of Law and Economics. Constitutional Political Economy, 28(1), 48–61.

Rivas, M. F. (2013). An experiment on corruption and gender. Bulletin of Economic Research, 65(1), 10–42.

Rowley, C. K., & Houser, D. (2012). The life and times of Gordon Tullock. Public Choice, 152(1), 3–27.

Schram, A., Brandts, J., & Gërxhani, K. (2019). Social-status ranking: A hidden channel to gender inequality under competition. Experimental Economics, 22(2), 396–418.

Schulze, G., & Franck, B. (2003). Deterrence versus intrinsic motivation: Experimental evidence on the determinants of corruptility. Economics of Governance, 4(2), 143–160.

Serra, D. (2012). Combining top-down and bottom-up accountability: Evidence from a bribery experiment. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 28(3), 569–587.

Stensöta, H., & Wängnerud, L. (2018). Gender and corruption: Historical roots and new avenues for research. Springer.

Stensöta, H. O., Wängnerud, L., & Agerberg, M. (2015). Why women in encompassing welfare states punish corrupt political parties. In C. Dahlstrom & L. Wängnerud (Eds.), Elites, institutions and the quality of government (pp. 245–262). Palgrave Macmillan.

Sundström, A., & Wängnerud, L. (2016). Corruption as an obstacle to women’s political representation: Evidence from local councils in 18 European countries. Party Politics, 22(3), 354–369.

Swamy, A., Knack, S., Lee, Y., & Azfar, O. (2001). Gender and corruption. Journal of Development Economics, 64(1), 25–55.

Torgler, B., & Valev, N. T. (2010). Gender and public attitudes toward corruption and tax evasion. Contemporary Economic Policy, 28(4), 554–568.

Treisman, D. (2000). The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 399–457.

Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. Economic Inquiry, 5(3), 224–232.

Tullock, G. (1975). The transitional gains trap. The Bell Journal of Economics, 6(2), 671–678.

Tullock, G. (1980). Efficient rent-seeking. In J. M. Buchanan, R. D. Tollison, & G. Tullock (Eds.), Toward a theory of the rent-seeking society (pp. 97–112). Texas A&M University Press.

Tullock, G. (1985). Efficient rents 3 back to the bog. Public Choice, 46(3), 259–263.

Tullock, G. (1987). Rent seeking. In J. Eatwell, M. Milgate, & P. Newman (Eds.), The new Palgrave: A dictionary of economics (Vol. 4, pp. 147–149). Macmillan Press.

Tullock, G. (1988). The costs of rent seeking: A metaphysical problem. Public Choice, 57(1), 15–24.

Tullock, G. (1996). Corruption theory and practice. Contemporary Economic Policy, 14(3), 6–13.

Vijayalakshmi, V. (2008). Rent-seeking and gender in local governance. The Journal of Development Studies, 44(9), 1262–1288.

Zhuravleva, T. (2015). Does the Russian government pay a fair wage: Review of studies. Voprosy Economiki, 11.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to William F. Shughart II, Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard, and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. We thank Elliott Ash, Richard Elliott, Alexander Nesterov, Arthur Schram, Alexander Stremitzer, and the seminar audience at ETH Zurich and the Higher School of Economics in St. Petersburg, for helpful discussions and suggestions. The article was prepared within the framework of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Financial support from European University Institute and Copenhagen Business School is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in this research were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution at which the research was conducted.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guerra, A., Zhuravleva, T. Do women always behave as corruption cleaners?. Public Choice 191, 173–192 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00959-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00959-5