Abstract

Automobiles are central to participation in economic, social, and cultural activities in the United States. The ability to drive as one ages is fundamental to the quality of life among older adults. Driving rates decline significantly with age. Researchers using cross-sectional data have studied the reasons former drivers have stopped driving, but few have followed individuals over time to examine changes in relationships among driving cessation, socio-demographics, and health conditions. We used longitudinal data from a national sample of 20,000 observations from the University of Michigan Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to examine relationships among demographic variables, health conditions, and driving reduction and driving cessation. Longitudinal data allow analysis of generational differences in behavior, a major advantage over cross-sectional data which only allow comparisons of different people at one point in time. We found, like many other studies, that personal decisions to limit and eventually stop driving vary with sex, age, and health conditions. In addition, unlike most previous studies, we also found that those relationships differ by birth cohort with younger cohorts less likely to stop and limit their driving than their older counterparts. The findings indicate an evolution in the association between driving cessation and its causes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Automobiles are central to participation in economic, social, and cultural activities in the United States. The ability to continue driving as one ages is consequently a fundamental determinant of the quality of life among older adults (Coughlin 2009). Data from the 2017 National Household Travel Survey (NHTS) reveal that most people (82%) over the age of 65-drive. Older adults made 86 % of their trips by automobile, 66 % as drivers and 20 % as passengers (Federal Highway Administration 2018). The population of the United States is aging rapidly and by 2060 almost a quarter of its population is predicted to be older than 65, the age most often used to identify older adults (Colby and Ortman 2015). As the population ages, it is more important than ever that policymakers understand decisions people make to limit and eventually to cease driving and the implications of these decisions for the wellbeing of older Americans.

While driving is common among older adults, driving rates decline significantly with age as health, cognitive ability, and other factors necessitate giving up driving. Driving cessation is a complex process. Many older adults first gradually limit driving by traveling only during daylight hours, avoiding driving in bad weather, using only familiar routes, visiting destinations near home, or making only essential trips (Ang et al. 2019). Older drivers sometimes substitute longer routes that require multiple right turns for shorter ones that require left turns ahead of oncoming traffic (Rosenbloom 2003), and some older drivers have reported relying on “copiloting” by their passengers who assist by providing directions and information on road conditions as they travel together (Bryden et al. 2014). With the involvement of family members, friends, doctors, and licensing authorities (Chipman et al. 1998), eventually some older adults stop driving entirely.

There is a substantial body of research on the determinants of driving limitation and cessation in the U.S. Much of the research on this topic relies on cross-sectional data, while asserting the potential explanatory effects of birth cohorts (Edwards et al. 2008)—groups of individuals who may have share experiences based on their generation that shape their behavior. In this paper, we directly examine relationship between older adults, cohorts, and driving limitation and cessation using a unique longitudinal database, the Health and Retirement Survey (HRS). Our analysis shows that older adults cease or limit driving as they age in ways consistent with previous research. In addition, our statistical models indicate that after taking age, gender, and health variables into account, cohort membership also contributes to differences in the rates with which older adults cease or limit their driving. Members of more recent cohorts are less likely to stop and limit their driving than their older counterparts. The findings confirm previous speculation and indicate an evolution in the association between driving cessation and its causes that should be considered by transportation planners and gerontologists.

Understanding the determinants of driving reduction and cessation

Over time, the percentage of older people who drive has grown due to improved health and longer life expectancies among older adults, increasing disposable income, the continuation of patterns established in their younger years, and—resulting from all of these factors—an increase in the proportion of older adults who are licensed to drive (Coughlin 2009). Despite the prevalence and growth of automobile travel among older adults, driving rates decline with age. Figure 1 shows that travel by automobile remains high for all older age groups, but the percentage who travel as passengers increases in parallel with the percentage of older adults who are non-drivers. The large literature on aging and driving emphasizes safety, fatal and injury crashes, and related issues such as licensing regulations (Dugan et al. 2013). These issues are critically important, but we focus here on research that addresses the social and individual processes that lead people to limit or stop driving as well as related studies that suggest a potential role for cohort effects in shaping driving outcomes.

A number of studies address determinants of self-regulation or limitation of driving leading eventually to driving cessation (Ang et al. 2019; Baldock et al. 2006; Gwyther and Holland 2012; Molnar and Eby 2008). We do not attempt to review this body of literature but selectively highlight research showing the role of five sets of factors that help to explain this process: individual characteristics, household characteristics, social networks, environmental conditions, and characteristics of the area in which older adults live. As we note above, most of these studies rely on cross-sectional data and thus are comparisons of different age groups at a single point in time (Rosenbloom 2012; Siren and Haustein 2016). We then turn to evidence that suggests an important role for cohorts—groups of older adults born in the same decade whose behavior as they age is potentially defined by their shared experience over past decades.

With respect to personal characteristics, driving behavior is strongly related to health. Driving limitation is associated with declining vision (Edwards et al. 2009; Ragland et al. 2004) and strongly and positively associated with stroke, dementia, heart failure, cognitive decline, and the medications used to treat these conditions (Dickerson et al. 2019; Edwards et al. 2010; Ray et al. 1993). Sex and race are highly correlated with the likelihood of giving up driving; women and non-white older adults have higher rates of driving cessation at every age, controlling for other factors (Babulal et al. 2018; Bauer et al. 2003; Choi et al. 2012c; Rosenbloom 2001). Finally, driving cessation is influenced by previous driving experience—the length of time and level of one’s driving activity (Hakamies-Blomqvist and Siren 2003)—a characteristic shaped by many other factors.

Household characteristics also influence driving decisions. Transitions away from driving may be easier if the household includes other drivers who are available to provide rides (Choi et al. 2012a). Transportation support from friends, neighbors, organizations, and agencies can also ease the transition away from driving (Choi et al. 2012a). At the same time, pressure from friends and/or doctors can persuade older adults to reduce and eventually stop driving (Adler and Rottunda 2006; Connell et al. 2013). Household income is negatively associated with the decision to give up driving among older drivers just as it is for working-age adults. Many older adults live on fixed incomes and may not have the resources to own and maintain private vehicles (Choi et al. 2012c; Vivoda et al. 2020).

Environmental conditions can cause drivers to reduce car travel. The most common responses to environmental conditions include avoiding driving in bad weather, at night, or on high-speed roads and highways (Naumann et al. 2011). Geographic differences in road conditions help explain relationships between driving status and neighborhood characteristics. Vivoda et al. (2017) find a positive relationship between both driving cessation and driving reduction and roadway density and congestion. These findings are consistent with those of other studies showing that older adults experience increased anxiety when driving under congested conditions or in speeding traffic (Hakamies-Blomqvist and Wahlström 1998).

Congestion tends to be highest in dense urban areas where activities are geographically concentrated. These are often neighborhoods in which alternative transportation services (e.g. public transit, taxis, paratransit, ridehail) are most available and access to destinations by foot is greatest, both factors potentially influencing the willingness of older adults to give up driving. Among older adults who no longer have driver’s licenses, those who live in urban areas and areas where destinations are in walking distance are more likely than other older adults to use transit and to walk, controlling for other factors including health status (Kim 2011). Data from the Health and Retirement Survey used in this study also show positive associations between driving cessation and living in high-density neighborhoods (Schouten et al. forthcoming).

Studies of cohorts as they age can reveal the long-term influence of shared generational experiences that are not discoverable using cross-sectional data. The benefits of longitudinal analysis—following older adults over time—is the basis for the Longitudinal Research on Aging Drivers (LongROAD) project, a prospective cohort study designed to understand the factors that influence safety during the aging process (Li et al. 2017; Molnar et al. 2015). These data will provide useful findings moving forward. However, current research suggests a role for retrospective analysis, as more recent cohorts of older adults may behave in ways different from previous generations of older adults.

As we note above, health is an important determinant of driving. Studies show that more recent cohorts of older adults live longer and spend less time in worse health than older cohorts of adults (Chatterji et al. 2015; Christensen et al. 2009; Dodge et al. 2014), although some evidence suggests that these health benefits have occurred only among the wealthiest adults (de la Fuente et al. 2019). If recent cohorts of older adults are healthier than older cohorts, they also are likely to drive longer.

The tendency to drive longer may be facilitated by recent technological changes such as automobile safety improvements that increase comfort with driving at older ages (Eby et al. 2016). Advanced vehicle technology (e.g. automatic emergency braking, blind spot and lane departure warning, navigation assistance) may make older adults feel safer and, therefore, extend their automobile use. Older adults tend to have low technology adoption rates (Coughlin 2009). The effect of these new innovations on the driving behavior of older adults, therefore, will rest on their value, usability, affordability, accessibility, technical support, social support, emotion, independence, experience, and confidence (Coughlin 2009). Reliance on new technology is an example of a cohort effect. Members of the oldest cohorts are least comfortable with technological driving assists, which are more broadly accepted by younger cohorts (Chiu et al. 2016; Vogels 2019).

While safety improvements may increase driving among older adults, advances in information and communication technologies (ICTs) may enable access to opportunities without driving. Although more resistant to the use of technology than younger adults, many members of recent older adult cohorts have experience using computers, smart phones, and the internet while members of earlier cohorts do not. In fact, their use of these technologies has increased over time. Seventy three percentages of those ages 65 and older use the internet and more than half (53 %) are smartphone owners (Livingston 2019). While their use of technology continues to lag that of younger adults, older adults today are more likely than older adults of previous generations to use technology (Gilleard and Higgs 2008; Hunsaker and Hargittai 2018) and, therefore, may be more likely to take advantage of technology-based alternatives to driving such as ridehailing or on-line shopping (Mitra et al. 2019). The proportion of older adults who use these services is climbing rapidly as cohorts who grew older having internet access enter post-retirement years (Shirgaokar et al. forthcoming).

Finally, shifting gender norms also may contribute to increased driving among recent older adult cohorts. Women’s labor force participation has increased rapidly over time, growing from 38 % to 1960 to 57 % in 2018 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020), requiring many women to balance paid employment while shouldering primary responsibility for unpaid household labor (Sayer 2016). Juggling work and non-work responsibilities often requires women to take multiple trips on a single tour—for example traveling from home to the child care center and then to work (McGuckin and Murakami 1999), a trip pattern more easily made by automobile than by other modes (Blumenberg 2016; Hensher and Reyes 2000).

Women’s driver’s licensing rates increased in parallel with their growing presence in the labor force. Women of every age were much less likely than men to be licensed to drive five decades ago but licensure rates today are approximately equal among men and women (Sivak 2013). Although women continue to drive fewer miles than men, the gap has narrowed over time (Sivak 2013). Consequently, more recent cohorts of older women will have had greater experience driving than older cohorts and, therefore, and can be expected to drive longer as they age. Licensing data are suggestive of this trend. From 1995 to 2010 there was a significant increase in licensing among women 55 and older as a percentage of their age group (Sivak and Schoettle 2012).

Data and methodology

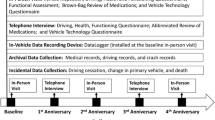

To explore relationships among age, cohort membership, and changes in driving behavior, we analyzed data from the national Health and Retirement Study (HRS). First administered in 1992, the HRS is a panel survey comprised of a representative sample of roughly 20,000 older Americans. Participants were interviewed biennially, with data collected on a wide range of characteristics related to health, family, employment, finances, and physical activity. New participants were recruited in later waves of the survey to insure its representativeness and continuity over time. Figure 2 shows the years in which the survey was administered and the age ranges of the respondents in those years. Importantly for this analysis, the HRS includes information about respondents’ driving habits. All survey participants age 65 and older were asked if they were able to drive. Those who indicated that they were able to drive were asked whether they limited their driving to short trips near their homes or whether they drove on longer trips as well.

Responses to these two survey items—whether or not an individual was able to drive and whether or not that person limited his or her driving—were our outcomes of interest. To address correlations between these outcomes and the rich set of variables available in the HRS, we specified a series of discrete-time logistic regression models. Discrete-time logistic regression is a common modeling strategy for analyzing event histories (Allison 1982). In this study, discrete-time modeling allowed us to explore whether driving cessation and driving limitation were correlated with key dependent variables such as age, gender, and birth cohort.

We specified two sets of models to address our research questions. In all models, an individual’s driving behavior in consecutive survey waves was the dependent variable. In models of driving cessation, a binary outcome measure indicated whether the respondent continued driving from wave a to wave b, or stopped driving between waves a and b. The outcome measure in the driving limitation models was similar, indicating whether a driver began to limit his or her driving between waves a and b, or whether he or she continued as an “unlimited” driver over consecutive waves. In addition to the primary variables of interest (age, gender, and cohort), all models included a suite of other control variables associated with the driving behavior of older adults. These included measures of health, family structure, residential location, and demographic and socioeconomic indicators.

The first set of models, which we term “pooled models,” included the entire sample of older adults. In the pooled models, the coefficient of the “cohort” variable provided a direct measure of the relationship between an individual’s birth cohort and changes in his or her driving behavior. Most importantly, the magnitude of this coefficient allowed us to evaluate whether, all else equal, members of a given cohort were more or less likely to stop or limit their driving than their counterparts in previous or subsequent cohorts. In addition to these base pooled models, we developed models with interaction terms. The first of these interaction models included a “cohort * age” term that provided an understanding of whether, all else equal, the relationship between age and stopping or limiting driving differed by cohort. A second series of interaction models included a “cohort * gender” term that evaluated whether the relationship between gender and driving behavior differed by cohort.

In addition to these pooled models, we also specified a second set of models which we labeled “cohort models.” These models investigated associations between changes in driving behavior and several independent variables. Unlike the pooled models, the cohort models examined these relationships separately for each cohort. These models have two purposes. First, because the cohort models included a respondent’s age as an independent variable, they served as a robustness test for the pooled models. Specifically, the cohort * age and the cohort * gender interaction terms in the pooled models and the age and gender variables in the cohort models both assessed the same relationship—the degree to which the driving behavior of members of a given cohort differed, either as they aged or by gender. Consequently, the coefficients of these terms should reflect a consistent association between age, gender, cohort, and changes in driving behavior across models.

Second, the cohort models also allowed us to examine associations among age, gender, and cohort in more detail than the pooled models. Of particular interest is whether the relationship between age and driving behavior differed by gender, and whether associations among age, gender, and driving behavior differed by cohort. While these relationships can be assessed using pooled data, this would require a triple interaction term (cohort * age * gender), making analysis and interpretation of the findings rather complex. To obtain more straightforward and interpretable results, we examined associations among age, gender, and cohort using the interaction of two variables (age * gender) in separate cohort models.

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics for the sample, which includes three HRS cohorts: the oldest cohort is comprised of people born in 1923 or earlier, the middle cohort includes respondents born between 1924 and 1930, and the youngest cohort contains respondents born between 1931 and 1941.

Results

Pooled models

Table 2 presents the results from the pooled models. Control variables in the base models generally have the expected relationship with both stopping and limiting driving. Not surprisingly, health-related variables are powerful predictors of driving cessation and limitation. Those reporting declining health between survey waves and those suffering from major ailments and conditions were far more likely to stop or limit driving than those without major health issues. Having had a stroke is strongly associated with an increased likelihood of stopping or limiting driving. Self-reported failing eyesight also has the expected relationship with driving; respondents’ likelihood of stopping or limiting driving increased as their vision declined.

Age has the expected correlation with changes in driving behavior; respondents became more likely to stop driving as they aged. Each additional year of age is associated with an approximately 10 % increase in the likelihood of stopping driving. Put differently, aging a decade is associated with a three-fold increase in the predicted likelihood of driving cessation. The relationship between advancing age and limiting driving is similarly positive but less pronounced; aging 1 year is correlated with a 5 % increase in the propensity to limit driving, which translates into a 1.6 times greater likelihood of limiting driving over a 10-year period.

Gender, like age, is also strongly correlated with driving cessation and limitation. As found in many previous studies (Bauer et al. 2003; Choi et al. 2012b), men are far less likely to stop or limit their driving than women. All else equal, men are 41 % less likely to stop driving than female respondents. Patterns are similar for limiting driving, with men being 50 % less likely to limit their driving than comparable women.

Variables describing household characteristics and family structure are also associated with changes in driving behavior. Wealth, for example, has a clear negative correlation with decisions to reduce or stop driving. Living with a partner, while not predictive of stopping driving, is a determinant of limiting driving. All else equal, those who lived in a couple household were less likely to limit their driving than those who did not live with a partner. Having nearby family members also is associated with driving behavior: older adults who did not have children living within ten miles of their homes were less likely to stop or curtail their driving, perhaps reflecting their inability to rely on nearby family members to provide mobility.

Race is a consistent predictor of stopping and limiting driving. Both Black and Hispanic respondents were substantially more likely to stop and limit their driving than non-Hispanic whites. Results also show correlations between residential location characteristics and driving behavior. Population density is positively associated with driving cessation, suggesting that those who lived in denser neighborhoods—areas that tend to have more non-auto transportation options—were more likely to stop driving than residents of more car-centric communities.

The pooled base models show clear associations between changes in driving behavior and cohort. Younger cohorts were less likely to stop and limit their driving than their older counterparts. Relative to members of the oldest cohort, members of the middle cohort were 23 % less likely to give up driving and 32 % less likely to limit their driving. Members of the youngest cohort showed an even lower propensity to stop and limit their driving: they were 35 % and 49 % less likely to stop and limit their driving, respectively, than those in the oldest cohort.

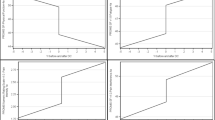

The results of the interaction models reveal that, in addition to the base cohort effects described above, associations between age, gender, and driving behavior or also differ depending upon one’s cohort. Models that include a “cohort * age” interaction term enabled us to evaluate how the relationship between aging and driving behavior differs between cohorts. The interaction term shows that while increased age is associated with a higher likelihood of stopping and limiting driving for members of all groups, this correlation is weaker among the younger cohorts. Compared to the oldest cohort, an additional year of age is associated with a 3 % lower likelihood of stopping driving for the middle cohort and a 2.3 % lower probability of driving cessation for the youngest cohort. Results for the driving limitation model are similar: for members of the middle cohort, an additional year of age is correlated with a 2.6 % lower likelihood of limiting driving compared to those in the oldest cohort; for the youngest cohort, an additional year corresponds to a 5.2 % decline in the likelihood of limiting driving, all else equal. Figure 3 illustrates the predicted likelihood that members of the middle and youngest cohorts will stop driving as they age, relative to the oldest cohort. Figure 4 shows the same relationship as it pertains to driving limitation.

Associations between gender and driving behavior are also attenuated by cohort. The results of the base model, discussed above, show that all else equal, men are far less likely to stop and limit their driving than women. However, the findings of models which contain cohort * gender interaction terms suggest that, at least with regard to driving cessation, the gender gap is less pronounced among younger cohorts.

The interpretation of interactions between two categorical variables is rather complex; depending on the groups being compared, the main effects often must be considered in combination with the interaction terms. We, therefore, discuss the results of the cohort * gender interaction models using fitted values. These values, presented in Figs. 5 and 6, highlight the gap in driving cessation and limitation between men and women for each cohort.

Figure 5 clearly shows that, relative to the oldest cohort, gender differences in stopping driving narrowed in the middle and youngest cohorts. All else equal, men in the oldest cohort were just over 9 percentage points more likely to stop driving than women in the same cohort. Among members of the middle and youngest cohort, the male-female gap in driving cessation was substantially smaller, at 4.7 and 4.6 percentage points respectively. Figure 6 suggests that the narrowing gender gap is limited to driving cessation: with regard to limiting driving, differences between men and women are relatively consistent across cohorts, with men’s predicted likelihood of limiting driving roughly 15 to 18 percentage points lower than women’s.

Cohort models

Tables 3 and 4 include the results of the cohort models. Table 3 contains the results of the driving cessation models and Table 4 provides results of the driving limitation models.

The analysis of each cohort consists of a base model (Models 1, 3, and 5) and a model that includes the interaction between age and gender (Models 2, 4, and 6).

As we mentioned in the section on data and methodology, one purpose of the cohort models is to serve as a robustness check of our pooled model results. In particular, we focus on the interaction terms in the pooled models: age and gender. While comparing coefficients from different logistic regression models poses some methodological challenges (Allison 1982; Mood 2010), we make such comparisons to validate to the findings of our pooled models and not to make firm conclusions regarding the magnitude of differences between cohorts.

With regard to age, results of the cohort models echo the pooled models, with the association between increasing age and stopping or limiting driving being somewhat weaker in the younger cohorts. The relationship between increasing age and stopping driving is strongest among the members of the oldest cohort. Members of that cohort are 13 % more likely to stop driving each year. By contrast, individuals in the subsequent, or middle, cohort are somewhat less likely to stop driving as they age: each additional year of age is associated with a 9 % increase in the likelihood of stopping driving. Members of the youngest cohort also gave up driving later than those in the oldest cohort; however, they were slightly more likely to give up driving as they aged than those in the middle cohort. An additional year of age was associated with a 10 % increase in the likelihood of stopping driving among older adults in the youngest cohort.

The models show similar relationships for driving limitation. Respondents in the oldest of the three cohorts were the most likely to limit their driving as they aged, becoming 9 % more likely to limit their driving with each additional year. Unlike the association between age and stopping driving, however, the relationship between age and driving limitation continues to weaken with each subsequent cohort: aging 1 year is associated with a 6 % higher likelihood of limiting driving for members of the middle cohort, while an additional year is associated with only a 3 % increase in the propensity to limit driving for those in the youngest cohort. Figure 4 shows the predicted likelihood that members of the three cohorts stopped driving as they aged.

Like age, the predictive power of gender as a determinant of driving cessation is strongest among respondents in the oldest cohort. Among members of that cohort, men were 46 % less likely to stop driving than women. In subsequent cohorts, this relationship weakens somewhat. Men in the middle cohort were 34 % less likely to stop driving than women, while male members of the youngest cohort were 39 % less likely to give up driving than women. Similar to the pooled models, we once again find that the weakening strength of gender as a predictor of driving behavior only applies to driving cessation; for driving limitation gender is a relatively stable predictor of limiting driving across cohorts.

Results of the cohort models confirm the findings of the pooled models and suggest that, at least to some degree, both age and gender were stronger predictors of changes in driving behavior among older cohorts: members of the oldest cohort were the earliest to give up driving as they age, and the gender gap in driving cessation was most pronounced among the oldest members of the population. However, one issue that the base cohort models did not address was how the relationship between age and gender changes by cohort. Are women more (or less) likely than men to give up driving sooner as they get older? And if so, does this difference change by cohort? To address these questions, we examined a series of cohort interaction models, the results of which are included in Table 4.

Almost universally, the interaction models demonstrate, regardless of cohort, that men and women stopped and limited their driving at the same rate as they aged. The lack of significance of the interaction terms suggests that both within and between cohorts, age does not have an additive (or subtractive) effect on driving behavior: neither men nor women became increasingly likely to change their driving behavior as they aged, while, all else equal, women were far more likely to stop or limit their driving than men. The sole exception to this with regard to limiting driving was found in the middle cohort. Relative to women, an additional year of age for men is associated with a modest 3 % increase in the likelihood of limiting driving. While this translates into a roughly 39 % higher likelihood of men limiting driving relative to women, the increased rate of driving limitation among middle-cohort men narrows—but does not close—the baseline gap in driving limitation between the sexes. Even among the oldest members of the middle cohort, women were substantially more likely to limit their driving than men.

Figure 7 shows the results of the interaction models to illustrate the predicted likelihood of stopping driving by age, gender, and cohort. Once again, as these are cross-model comparisons, we use these predicted values to provide a general sense of trends among different combinations of cohort and gender, and not to make firm conclusions regarding the magnitude of differences between cohorts.

Figure 5 demonstrates how the age coefficients described above cumulatively affect the members of various groups. While respondents in their late 60s, regardless of their gender or cohort, have a relatively low probability of stopping driving, the rate of driving cessation among individuals in the oldest cohort increases far more rapidly than for those in other cohorts. Figure 7 also illustrates the relationship between age and gender. As described above, neither men nor women become increasingly likely to stop driving as they age. Nevertheless, small differences in the likelihood of stopping driving grow larger with age, particularly in the oldest cohort. Thus, while the male-to-female ratio in the likelihood of stopping driving changes very little over time, gender differences in driving cessation become larger with age.

Figure 8 illustrates associations between age, gender, and cohort and limiting driving. The similarities with Fig. 7 are clear, in that women and older cohorts limit their driving at much higher rates than men and younger cohorts, respectively. Figure 8 does, however, highlight some differences as well. In particular, while increases in the likelihood of driving limitation are relatively consistent in the oldest and youngest cohorts regardless of gender, trends are distinct among the middle cohort. For its members, the gender gap in limiting driving declines somewhat with age, as predicted rates of men’s driving limitation increase slightly faster than women.

Conclusions

In societies in which the vast majority of people drive automobiles, the transition from driver to non-driver associated with advancing age can greatly affect the quality of a person’s life. Often necessitated by declining health and frequently necessary to insure personal and public safety, reduction and eventual cessation of driving can be traumatic because it reduces access to shopping, health care, social, cultural, and religious activities, and makes a person more dependent on others. Late life driving cessation has been studied because of its importance in the fields of traffic safety and gerontology. But studies of driving cessation most often rely on cross-sectional data—comparing different people and their circumstances at one point in time. While very useful, this can explain associations only at one point in time, even if those relationships are dynamic. Relationships between age and driving have steadily evolved in ways that are better understood if cohorts are studied. Fewer people drove in past decades and today older people use ridehailing services differently than younger people and use on-line apps to select routes differently than younger cohorts. Men and women have long been observed to behave differently when it comes to driving cessation, but men and women have had different propensities to drive over the decades and this association could well be changing over time as their social and cultural determinants evolve.

By taking advantage of a unique longitudinal data base that followed people as they aged over more than 30 years, we were able to show that relationships among driving cessation, aging, and gender are indeed evolving. While age and gender continue to influence driving outcomes in the ways predicted by previous scholars, we find that more recent generations of older adults are driving longer. The largest differences are between the oldest cohort and the two more recent cohorts whose maturation occurred when there was widespread use of the automobile. Many older adults from this earlier generation never drove and, therefore, were not included in our sample. But it is also likely that adults in our oldest cohort spent less of their adults lives behind a wheel compared to those in more recent cohorts. Per capita vehicle registrations grew substantially from 1930 to 1990, increasing from 0.22 to 0.75 (Federal Highway Administration 1997; Federal Highway Administration various years; Population Estimates Program various dates). More recently, the growth in the number of vehicle registrations has slowed as automobile ownership has become almost universal; in 2000, 92 % of all households in the U.S. had at least one automobile (Ruggles et al. 2020).

The longitudinal data also show that, as we predicted, the gender gap in driving cessation has waned among recent cohorts of older adults. For the same reasons as men, women in recent cohorts likely had more driving experience than in earlier cohorts. Women’s need for automobility was further bolstered by suburbanization and increased labor force participation, a combination which made travel for household and work next to impossible by modes other than the automobile (Walsh 2004). Gender differences in driving limitation remained largely the same across cohorts, perhaps due to underlying attitudinal differences between men and women (D’Ambrosio et al. 2008; Gwyther and Holland 2012) or women’s greater willingness to rely on driving alternatives (Barrett et al. 2018). Finally, our models show that regardless of cohort, men and women stopped and limited their driving at the same rate as they aged.

Reliance on automobiles remains important because almost three-quarters of older Americans live in low-density suburban or rural areas (Kostyniuk et al. 2000) where alternative transportation options are limited (Glasgow and Blakely 2000). Even in dense urban areas, older adults may have difficulty walking, including walking to and from bus stops and stations and may prefer to travel by automobile. Driving means retaining functional independence and personal autonomy, but that must be balanced against the fact that older drivers incur increasing risk of injury and death from vehicular crashes compared to other age groups (Dickerson et al. 2007). Driving cessation reduces crash risk but has been associated with negative consequences for psychosocial and physical well-being, including decreased out-of-home activity levels (Marottoli et al. 2000), reduced networks of friends (Mezuk and Rebok 2008) perhaps leading to increased depression (Fonda et al. 2001; Marottoli et al. 1997) and accelerated health decline (Edwards et al. 2009).

The findings suggest three policy approaches. First, if older adults continue to drive as they age, policymakers ought to target automobile and road safety improvements to this growing segment of the population. These could include continued improvements in advanced vehicle technologies as well as targeted efforts to encourage technological adoption among this age group. Second, efforts should be made to increase older adults’ use of “auto-access” services that allow the benefits of automobility without driving. For example, some older adults may be uncomfortable using ridehailing applications but might take advance of these services if there were intermediaries who booked their rides (Shirgaokar et al. forthcoming). Third, able-bodied older adults who live in dense urban areas could benefit from urban design improvements that make it easier for them to walk. A recent study showed that elderly residents of dense, walkable, inner-city communities served well by transit preferred not to walk or ride transit because they were fearful of being victimized by criminals and concerned about littered streets and speeding traffic (Loukaitou-Sideris et al. 2019).

Policy should be based on expectations for the future rather than observation of past patterns, and cohort analysis enumerates how the future will differ from the past. To explore these changes in greater depth, our findings suggest the value of additional effort to collect more complete longitudinal data about travel and attitudes about travel as people age, complemented by qualitative analysis to better elucidate the causes of behavioral change.

References

Adler, G., Rottunda, S.: Older adults’ perspectives on driving cessation. J. Aging Stud. 20, 227–235 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2005.09.003

Allison, P.D.: Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories. Sociol. Methodol. 13, 61–98 (1982). https://doi.org/10.2307/270718

Ang, B.H., Oxley, J.A., Chen, W.S., Yap, K.K., Song, K.P., Lee, S.W.H.: To reduce or to cease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative studies on self-regulation of driving. J. Safety Res. 70, 243–251 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2019.07.004

Babulal, G.M., Williams, M.M., Stout, S.H., Roe, C.M.: Driving outcomes among older adults: A systematic review on racial and ethnic differences over 20 Years. Geriatrics. 3, 12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3010012

Baldock, M.R.J., Mathias, J.L., McLean, A.J., Berndt, A.: Self-regulation of driving and its relationship to driving ability among older adults. Accid. Anal. Prev. 38, 1038–1045 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2006.04.016

Barrett, A.E., Gumber, C., Douglas, R.: Explaining gender differences in self-regulated driving: What roles do health limitations and driving alternatives play? Ageing Soc. 38, 2122–2145 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X17000538

Bauer, M.J., Adler, G., Kuskowski, M.A., Rottunda, S.: The influence of age and gender on the driving patterns of older adults. J. Women Aging. 15, 3–16 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1300/J074v15n04_02

Blumenberg, E.: Why low-income women in the US still need automobiles. Town Plan. Rev. 87, 525–545 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2016.34

Bryden, K.J., Charlton, J., Oxley, J., Lowndes, G.: Older driver and passenger collaboration for wayfinding in unfamiliar areas. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 38, 378–385 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414531466

Chatterji, S., Byles, J., Cutler, D., Seeman, T., Verdes, E.: Health, functioning, and disability in older adults—present status and future implications. Lancet. 385, 563–575 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61462-8

Chipman, M.L., Payne, J., McDonough, P.: To drive or not to drive: The influence of social factors on the decisions of elderly drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 30, 299–304 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-4575(97)00107-3

Chiu, C.-J., Hu, Y.-H., Lin, D.-C., Chang, F.-Y., Chang, C.-S., Lai, C.-F.: The attitudes, impact, and learning needs of older adults using apps on touchscreen mobile devices: Results from a pilot study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 63, 189–197 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.020

Choi, M., Adams, K.B., Kahana, E.: The impact of transportation support on driving cessation among community-dwelling older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 67B, 392–400 (2012a). https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs035.

Choi, M., Mezuk, B., Lohman, M.C., Edwards, J.D., Rebok, G.W.: Gender and racial disparities in driving cessation among older adults. J. Aging Health. 24, 1364–1379 (2012b). https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264312460574 )(b).

Choi, M., Mezuk, B., Rebok, G.W.: Voluntary and involuntary driving cessation in later life. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 55, 367–376: (2012c). https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2011.642473

Christensen, K., Doblhammer, G., Rau, R., Vaupel, J.W.: Ageing populations: The challenges ahead. Lancet. 374, 1196–1208 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4

Colby, S.L., Ortman, J.M.: Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C. (2015)

Connell, C.M., Harmon, A., Janevic, M.R., Kostyniuk, L.P.: Older adults’ driving reduction and cessation: Perspectives of adult children. J. Appl. Gerontol. 32, 975–996 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464812448962

Coughlin, J.F.: Longevity, lifestyle, and anticipating the new demands of aging on the transportation system. Public Works Manag. Policy. 13, 301–311 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X09335609

D’Ambrosio, L.A., Donorfio, L.K.M., Coughlin, J., Mohyde, M., Meyer, J.: Gender Differences in Self-regulation patterns and attitudes toward driving among older adults. J. Women Aging. 20, 265–282 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/08952840801984758

Dickerson, A.E., Molnar, L.J., Bédard, M., Eby, D.W., Berg-Weger, M., Choi, M., Grigg, J., Horowitz, A., Meuser, T., Myers, A., O’Connor, M., Silverstein, N.M.: Transportation and aging: An updated research agenda to advance safe mobility among older adults transitioning from driving to non-driving. Gerontologist. 59, 215–221 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx120

Dickerson, A.E., Molnar, L.J., Eby, D.W., Adler, G., Bédard, M., Berg-Weger, M., Classen, S., Foley, D., Horowitz, A., Kerschner, H., Page, O., Silverstein, N.M., Staplin, L., Trujillo, L.: Transportation and aging: A research agenda for advancing safe mobility. Gerontologist. 47, 578–590 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/47.5.578

Dodge, H.H., Zhu, J., Lee, C.-W., Chang, C.-C.H., Ganguli, M.: Cohort effects in age-associated cognitive trajectories. J. Gerontol. Ser. A. 69, 687–694 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glt181

Dugan, E., Barton, K.N., Coyle, C., Lee, C.M.: U.S. policies to enhance older driver safety: A systematic review of the literature. J. Aging Soc. Policy. 25, 335–352 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2013.816163

Eby, D.W., Molnar, L.J., Zhang, L., St. Louis, R.M., Zanier, N., Kostyniuk, L.P., Stanciu, S.: Use, perceptions, and benefits of automotive technologies among aging drivers. Inj. Epidemiol. 3, 28 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-016-0093-4

Edwards, J.D., Bart, E., O’Connor, M.L., Cissell, G.: Ten years down the road: Predictors of driving cessation. Gerontologist. 50, 393–399 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp127

Edwards, J.D., Lunsman, M., Perkins, M., Rebok, G.W., Roth, D.L.: Driving cessation and health trajectories in older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A. 64A, 1290–1295 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glp114

Edwards, J.D., Ross, L.A., Ackerman, M.L., Small, B.J., Ball, K.K., Bradley, S., Dodson, J.E.: Longitudinal predictors of driving cessation among older adults from the ACTIVE clinical trial. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 63, P6–P12 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.1.P6

Federal Highway Administration: State Motor Vehicle Registrations, By Years, 1900–1995. U.S. Department of Transportation (1997)

Federal Highway Administration: 2017 National Household Travel Survey [data]. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C. (2018)

Federal Highway Administration: Highway Statistics. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C. (various years)

Fonda, S.J., Wallace, R.B., Herzog, A.R.: Changes in driving patterns and worsening depressive symptoms among older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 56, S343–S351 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/56.6.S343

de la Fuente, J., Caballero, F.F., Verdes, E., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F., Cabello, M., de la Torre-Luque, A., Sánchez-Niubó, A., María Haro, J., Ayuso-Mateos, J.L., Chatterji, S.: Are younger cohorts in the USA and England ageing better? Int. J. Epidemiol. 48, 1906–1913: (2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz126

Gilleard, C., Higgs, P.: Internet use and the digital divide in the English longitudinal study of ageing. Eur. J. Ageing. 5, 233–239 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-008-0083-7

Glasgow, N., Blakely, R.M.: Older nonmetropolitan residents’ evaluations of their transportation arrangements. J. Appl. Gerontol. 19, 95–116 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1177/073346480001900106

Gwyther, H., Holland, C.: The effect of age, gender and attitudes on self-regulation in driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 45, 19–28 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2011.11.022

Hakamies-Blomqvist, L., Siren, A.: Deconstructing a gender difference: Driving cessation and personal driving history of older women. J. Safety Res. 34, 383–388 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2003.09.008

Hakamies-Blomqvist, L., Wahlström, B.: Why do older drivers give up driving? Accid. Anal. Prev. 30, 305–312 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-4575(97)00106-1

Hensher, D.A., Reyes, A.J.: Trip chaining as a barrier to the propensity to use public transport. Transportation. 27, 341–361 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005246916731

Hunsaker, A., Hargittai, E.: A review of Internet use among older adults. New Media Soc. 20, 3937–3954 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818787348

Kim, S.: Transportation alternatives of the elderly after driving cessation. Transp. Res. Rec. 2265, 170–176 (2011). https://doi.org/10.3141/2265-19

Kostyniuk, L., Shope, J.T., Molnar, L.J.: Driving Reduction/Cessation Among Older Drivers: Toward a Behavioral Framework. Transportation Research Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (2000)

Li, G., Eby, D.W., Santos, R., Mielenz, T.J., Molnar, L.J., Strogatz, D., Betz, M.E., DiGuiseppi, C., Ryan, L.H., Jones, V., Pitts, S.I., Hill, L.L., DiMaggio, C.J., LeBlanc, D., Andrews, H.F.: Longitudinal research on aging drivers (LongROAD): Study design and methods. Inj. Epidemiol. 4, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-017-0121-z

Livingston, G.: Americans 60 and older are spending more time in front of their screens than a decade ago, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/18/americans-60-and-older-are-spending-more-time-in-front-of-their-screens-than-a-decade-ago/

Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Wachs, M., Pinski, M.: Toward a richer picture of the mobility needs of older Americans. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 85, 482–500 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1630295

Marottoli, R.A., de Leon, C.F.M., Glass, T.A., Williams, C.S., Cooney, L.M., Berkman, L.F.: Consequences of driving cessation. Decreased out-of-home activity levels. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 55, S334–S340 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/55.6.S334

Marottoli, R.A., de Leon, C.F.M., Glass, T.A., Williams, C.S., Cooney, L.M., Berkman, L.F., Tinetti, M.E.: Driving cessation and increased depressive symptoms: Prospective evidence from the New Haven EPESE. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 45, 202–206 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04508.x

McGuckin, N., Murakami, E.: Examining trip-chaining behavior: Comparison of travel by men and women. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board. 1693, 79–85 (1999). https://doi.org/10.3141/1693-12

Mezuk, B., Rebok, G.W.: Social integration and social support among older adults following driving cessation. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 63, 298–303 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.5.S298

Mitra, S.K., Bae, Y., Ritchie, S.G.: Use of ride-hailing services among older adults in the United States. Transp. Res. Rec. 2673, 700–710 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198119835511

Molnar, L.J., Eby, D.W.: The relationship between self-regulation and driving-related abilities in older drivers: An exploratory study. Traffic Inj. Prev. 9, 314–319 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/15389580801895319

Molnar, L.J., Eby, D.W., Zhang, L., Zanier, N., Louis, St, Kostyniuk, R.M.: Self-regulation of driving by older adults: A LongROAD Study. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety (2015)

Mood, C.: Logistic regression: Why we cannot do What we think we can do, and What we can do about it. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 26, 67–82 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006

Naumann, R.B., Dellinger, A.M., Kresnow, M.: Driving self-restriction in high-risk conditions: How do older drivers compare to others? J. Safety Res. 42, 67–71 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2010.12.001

Population Estimates Program: National Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, Washington, D.C. (various dates)

Ragland, D.R., Satariano, W.A., MacLeod, K.E.: Reasons given by older people for limitation or avoidance of driving. Gerontologist 44, 237–244 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.2.237

Ray, W.A., Thapa, P.B., Shorr, R.I.: Medications and the older driver. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 9, 413–438 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-0690(18)30413-0

Rosenbloom, S.: Driving cessation among older people: When does it happen and what impact does it have? Transp. Res. Rec. 1779, 93–99 (2001). https://doi.org/10.3141/1779-13

Rosenbloom, S.: The Mobility Needs of Older Americans: Implications for Transportation Reauthorization. Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy, Brookings Institution, Washington D.C. (2003)

Rosenbloom, S.: The travel and mobility needs of older people now and in the future. In: Coughlin, J.F., D’Ambrosio, L.A. (eds.) Aging America and Transportation. Personal Choices and Public Policy. Springer Publishing Company, New York (2012)

Ruggles, S., Flood, S., Goeken, R., Grover, J., Meyer, E., Pacas, J., Sobek, M.: IPUMS USA: Version 9.0 (American Community Survey and U.S. Census), http://usa.ipums.org

Sayer, L.C.: Trends in women’s and men’s time use, 1965–2012: Back to the future? In: McHale, S.M., King, V., Van Hook, J., Booth, A. (eds.) Gender and Couple Relationships, pp. 43–77. Springer International Publishing, Cambridge (2016)

Schouten, A., Blumenberg, E., Wachs, M., King, H.: Keys to the car: Driving cessation and residential location among older adults. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. (forthcoming)

Shirgaokar, M., Aditi, M., Agrawal, A., Wachs, M., Dobbs, B.: Differences in ride-hailing adoption across location types: Findings from California’s older adults. J. Transp. Land Use. (forthcoming)

Siren, A., Haustein, S.: How do baby boomers’ mobility patterns change with retirement? Ageing Soc. 36, 988–1007 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000100

Sivak, M.: Female drivers in the United States, 1963–2010: From a minority to a majority? Traffic Inj. Prev. 14, 259–260 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2012.755736

Sivak, M., Schoettle, B.: A note: The changing gender demographics of U.S. drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 13, 575–576 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2012.727110

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Women and aging affect trends in labor force growth, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/women-and-aging-affect-trends-in-labor-force-growth.htm

Vivoda, J.M., Heeringa, S.G., Schulz, A.J., Grengs, J., Connell, C.M.: The influence of the transportation environment on driving reduction and cessation. Gerontologist 57, 824–832 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw088

Vivoda, J.M., Walker, R.M., Cao, J., Koumoutzis, A.: How accumulated wealth affects driving reduction and cessation. Gerontologist 60, 1273–1281 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa039

Vogels, E.A.: Millennials stand out for their technology use, but older generations also embrace digital life. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (2019)

Walsh, M.: Gender and the Automobile in the United States, http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Gender/Walsh/G_Overview1.htm

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible through California Statewide Transportation Research Program funding received by the University of California Institute of Transportation Studies from the State of California through the Public Transportation Account and the Road Repair and Accountability Act of 2017 (Senate Bill 1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schouten, A., Wachs, M., Blumenberg, E.A. et al. Cohort analysis of driving cessation and limitation among older adults. Transportation 49, 841–865 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-021-10196-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-021-10196-2