Abstract

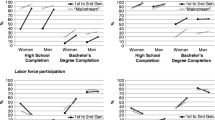

Economic inequality in the U.S. is significantly influenced by the integration trajectory of diverse immigrant and racial/ethnic minority groups. It is also increasingly clear that these processes are uniquely gendered. Few studies, however, jointly and systematically consider the complex ways in which race/ethnicity, gender, and nativity intersect to shape minority men’s and women’s economic experiences, and an intersectional understanding of these processes remains underdeveloped. To address this gap, we blend insights from assimilation, stratification, and intersectionality literatures to analyze 2015–2019 American Community Survey data. Specifically, we examine income inequality and group-level mobility among full-time working whites, Blacks, Native Americans, and Asian and Latino subgroups representative of the Southwest—the first U.S. region to reach a majority-minority demographic profile. Sociodemographic and human capital attributes generally reduce group-level income deficits, and we observe a robust pattern of economic mobility among native-born generations. But most groups remain decisively disadvantaged. Persistent income gaps signal multitiered racial/ethnic-gender hierarchies in the Southwest and suggest exclusion of minority men and women. Additionally, race/ethnicity and gender have an uneven impact on the relative position and progress observed among both U.S.- and foreign-born generations. Such findings support an intersectional approach and demonstrate the complex interplay of multiple axes of inequality that together shape contemporary U.S.- and foreign-born men’s and women’s economic experiences and returns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data used in this article are publicly available and can be accessed at https://usa.ipums.org/usa/.

Notes

We define the Southwest as: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah.

Given the confluence of race, ethnicity, and national origin, we use the term race/ethnicity. For a discussion as this relates to Census and ACS data, see Footnote 9. When discussing racial/ethnic and/or national origin groups (U.S.- and foreign-born), we employ the term ethnics to refer to members of these groups (e.g., Asian and Latino ethnics; Chinese and Mexican ethnics). For a critique of broad racialized pan-ethnic classifications, see DiPietro & Bursik (2012); Restifo & Mykyta (2019). For a discussion of the racialization of Hispanics and Latinos, see Ortiz & Telles (2012); Estrada et al. (2020).

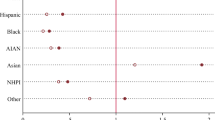

Estimates based on 2019 American Community Survey data.

The ACS does not directly ask respondents if they work full-time or part-time. Rather, respondents are asked to report the “usual” number of hours per week they worked the previous year and the number of weeks (Ruggles et al., 2021). Consistent with the U.S. Department of Labor (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020), we classify persons that reported working 35 hours or more per week as full-time. We also designate persons that reported working 48 weeks or more the previous year as full-year workers. We are unable to distinguish, however, between persons that worked 35 + hours per week, 48 + weeks per year at a single job versus those that did so at multiple part-time and/or partial-year jobs because: 1) the ACS does not provide information on whether respondents worked a single job the previous year or multiple jobs; and 2) the ACS does not provide the number of hours or weeks spent at each job for those working multiple jobs. The dataset provides only a single, primary occupation for each respondent (Ruggles et al., 2021). As such, respondents that worked multiple part-time and/or partial-year jobs that amounted to full-time, full-year work (35 + hours per week, 48 + weeks per year) are included in our analyses.

Part-time workers are in many ways unique and distinct from full-time workers. This includes access, participation, and movement in the labor market, as well as reason/purpose (economic vs. noneconomic; voluntary vs. involuntary) for working part-time (e.g., school, semi-retired, childcare, eldercare) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). By restricting our sample to persons working 35 + hours per week, 48 + weeks per year, we reduce conflating full-time and part-time workers and their experiences. Even so, we recognize that some full-time, full-year workers in our sample worked multiple part-time and/or partial-year jobs—though we cannot directly track it.

We estimate that only about 3% of full-time, full-year workers ages 25–55 in the Southwest live outside identified MSAs, with an additional 6% living in areas where metropolitan status is indeterminable.

We use detailed racial, ethnic, and national origin codes available via the ACS to construct the 10 above mentioned racial/ethnic group categories. Except for Mexicans, Guatemalans, and Salvadorans, all other racial/ethnic groups considered in our analyses consist of non-Latinos only. Native Americans include both American Indians and Alaskan Natives. In an effort to reduce potential ambiguities, multiracial respondents are not included in our analyses. Persons self-identifying as multiracial comprise a small fraction of cases (less than 2 percent) once we apply sample restrictions.

The U.S. Census Bureau, which administers the ACS, designates five broad racialized pan-ethnic categories for race: 1) white, 2) Black or African American, 3) American Indian or Alaska Native, 4) Asian, and 5) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (Jones et al., 2021). These five categories represent a general American conceptualization of race based on phenotype combined with ethnicity, national origin, and geographic region (OMB, 1997; see DiPietro & Bursik, 2012 for a critique of such classification schemes). The ACS questionnaire, when asking about race, provides survey respondents the first three racial categories (white, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native) to select from, as well as several specific Asian and Pacific Islander origin categories (e.g., Asian Indian, Chinese, Native Hawaiian, and Samoan). Survey respondents can also write in other specific Asian and Pacific Islander ethnic, cultural, and national origins (e.g., Hmong, Laotian, Fijian, Tongan)—all of which are designated in the ACS questionnaire as races (Ruggles et al., 2021). Importantly, the U.S. Census Bureau conceptualizes and treats Hispanic, Latino, and Spanish origin as distinct from race, and the ACS questionnaire asks a separate question about it. As such, Hispanic origin categories are independent of and cut across race. The ACS questionnaire provides survey respondents several specific Hispanic, Latino, and Spanish origin categories to select from (Mexican/Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban), and respondents can write in other specific Hispanic, Latino, and Spanish ethnic, cultural, and national origins (e.g., Colombian, Dominican, Guatemalan, Salvadoran) (Ruggles et al., 2021).

Foreign-born white, in this instance, consists exclusively of non-Latino white Europeans, while foreign-born Black is comprised of non-Latino Black Africans. Given the diversity (and to a certain extent, ambiguity) of groups clustered into U.S. Census race categories, we attempt to preserve a degree of focus and precision among foreign-born whites and Blacks for comparative purposes with other racial/ethnic groups. Native American does not present a foreign-born equivalent for comparison.

U.S.-born citizen and naturalized citizen are collapsed into the single category of U.S. citizen in analyses reported in Table 3 (where each race/ethnic group is stratified by nativity) to avoid model degradation due to collinearity tied to the inclusion of more detailed citizenship and race/ethnic-nativity measures—which diagnostic tests showed posed estimate problems.

We explored the possibility of introducing measures to account for age of U.S. entry (which also taps into whether individuals received their education in the U.S. or abroad) in our analyses. Diagnostic tests, however, revealed model degradation due to collinearity between age of U.S. entry and other key predictors. This was especially problematic with models presented in Table 3 where each race/ethnic group is distinguished by nativity.

We do not include measures for both age and work experience together in our models since age is directly factored into our calculation of work experience. We explored the possibility of substituting age and age-squared in our models for work experience and work experience-squared. Both sets of estimates were consistent and all major patterns held across the board.

We draw a distinction between public and private employment sectors because prior work shows racial/ethnic minorities and women experience more equitable treatment, opportunities, and mobility prospects in the public sector—though recent evidence suggests this is changing with the privatization of the public sector (Wilson, 1997, 2009; Wilson et al, 2015). In addition, public and private employment sectors show distinct tendencies for union membership. An estimated 34.8 percent of public-sector workers are union members compared to just 6.3 percent of private-sector workers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021).

Extended family members include any relative that is not the household head, his/her spouse, or his/her child.

Full results and interaction effect estimates from the pooled model are not shown but are available upon request.

All models include statistical controls for MSA (results not shown).

References

Adelman, R. M., & Tsao, H. (2016). Deep South demography: New immigrants and racial hierarchies. Sociological Spectrum, 36(6), 337–358.

Alba, R. D., & Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Harvard University Press.

Barringer, H. R., Takeuchi, D. T., & Xenos, P. (1990). Education, occupational prestige, and income of Asian Americans. Sociology of Education, 63(1), 826–874.

Bennett, T., Savage, M., Silva, E., Warde, A., Gayo-Cal, M., & Wright, D. (2009). Culture, Class, Distinction. Routledge.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2003). Understanding international differences in the gender pay gap. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(1), 106–144.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), 789–865.

Blau, F. D., Kahn, L. M., Moriarty, J. Y., & Souza, A. P. (2003). The role of the family in immigrants’ labor-market activity: An evaluation of alternative explanations: Comment. The American Economic Review, 93(1), 429–447.

Blea, I. (1992). La Chicana and the Intersection of Race, Class, and Gender. Praeger.

Bloemraad, I. (2006). Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada. University of California Press.

Bloemraad, I., Korteweg, A., & Yurdakul, G. (2008). Citizenship and immigration: Multiculturalism, assimilation, and challenges to the nation-state. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 153–179.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2004). From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(6), 931–950.

Borch, C., & Corra, M. K. (2010). Differences in earnings among black and white African immigrants in the United States, 1980–2000: A cross-sectional and temporal analysis. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 573–592.

Borjas, G. J. (1989). Economic theory and international migration. The International Migration Review, 23(3), 457–485.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

Browne, I., & Misra, J. (2003). The intersection of gender and race in the labor market. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 487–513.

Budiman, A., Tamir, C., Mora, L., & Noe-Bustamante, L. (2020). Statistical Portrait of the Foreign-Born Population in the United States, 2018. Pew Hispanic Center.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Monthly Labor Review: Who chooses part-time work and why? U.S. Department of Labor.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Employment Characteristics of Families—2019. U.S. Department of Labor.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). News Release: Union Members—2020. U.S. Department of Labor.

Castaño, A. M., Fontanil, Y., & García-Izquierdo, A. L. (2019). “Why can’t I become a manager?” —A systematic review of gender stereotypes and organizational discrimination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1–29.

Chapman, S. J., & Benis, N. (2017). Ceteris non paribus: The intersectionality of gender, race, and region in the gender wage gap. Women’s Studies International Forum, 65, 78–86.

Chiswick, B. R., Lee, Y. L., & Miller, P. W. (2005). A longitudinal analysis of immigrant occupational mobility: A test of the immigrant assimilation hypothesis. International Migration Review, 39(2), 332–353.

Choi, Y., He, M., & Harachi, T. W. (2008). Intergenerational cultural dissonance, parent–child conflict and bonding, and youth problem behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(1), 85–96.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge.

Connor, P. (2010). Explaining the refugee gap: Economic outcomes of refugees versus other immigrants. Journal of Refugee Studies, 23(3), 377–397.

Curran, S. R., Shafer, S., Donato, K. M., & Garip, F. (2006). Mapping gender and migration in sociological scholarship: Is it segregation or integration? International Migration Review, 40(1), 199–223.

Davis, J. J., Roscigno, V. J., & Wilson, G. (2016). American Indian poverty in the contemporary United States. Sociological Forum, 31(1), 5–28.

Davis, K. (2008). Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist Theory, 9(1), 67–85.

De Jong, G. F., & Madamba, A. D. (2001). A double disadvantage? Minority group, immigrant status, and underemployment in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 82(1), 117–130.

De Vroome, T., & Van Tubergen, F. (2010). The employment experience of refugees in the Netherlands. International Migration Review, 44(2), 376–403.

DeSilver, D. (2013). Global Inequality: How the U.S. Compares. Washington, DC, Pew Hispanic Center.

DiPietro, S. M., & Bursik, R. J., Jr. (2012). Studies of the new immigration: The dangers of pan-ethnic classifications. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 641, 247–267.

DiPrete, T. A., & Buchmann, C. (2013). The rise of women: The growing gender gap in education and what it means for American schools. The Russell Sage Foundation.

Doorn, D. J., & Kelly, K. A. (2015). Employment change in the US Census Divisions from 2000 through the Great Recession and current recovery. Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies, 15(2), 5–22.

Dumais, S. A. (2002). Cultural capital, gender, and school success: The role of habitus. Sociology of Education, 75(1), 44–68.

Duncan, B., & Trejo, S. J. (2015). Assessing the socioeconomic mobility and integration of US immigrants and their descendants. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 657(1), 108–135.

Elliott, J. R., & Smith, R. A. (2001). Ethnic matching of supervisors to subordinate work groups: Findings on “bottom-up” ascription and social closure. Social Problems, 48(2), 258–276.

Elliott, J. R., & Smith, R. A. (2004). Race, gender, and workplace power. American Sociological Review, 69(3), 365–386.

England, P., Levine, A., & Mishel, E. (2020). Progress toward gender equality in the United States has slowed or stalled. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(13), 6990–6997.

Estrada, E., Cabaniss, E., & Coury, S. (2020). Racialization of Latinx immigrants: The role of (seemingly) positive newspaper discourse. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 17(1), 125–146.

Feliciano, C. (2006). Unequal Origins: Immigrant Selection and the Education of the Second Generation. LFB Scholarly Publishing.

Frank, R., Akresh, I. R., & Lu, B. (2010). Latino immigrants and the US racial order: How and where do they fit in? American Sociological Review, 75(3), 378–401.

Fuligni, A. J., Tseng, V., & Lam, M. (1999). Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development, 70(4), 1030–1044.

Gans, H. J. (2005). Race as class. Contexts, 4(4), 17–21.

Glazer, N. (1971). Blacks and ethnic groups: The difference, and the political difference it makes. Social Problems, 18(4), 444–461.

Glenn, E. N. (1999). The social construction and institutionalization of gender and race: an integrative framework. In M. Marxerree, J. Lorber, & B. B. Hess (Eds.), Revising Gender (pp. 3–43). Sage Publications.

Glick, J. E., & Han, S. Y. (2015). Socioeconomic stratification from within: Changes within American Indian cohorts in the United States: 1990–2010. Population Research and Policy Review, 34(1), 77–112.

Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American Life. Oxford University Press.

Greenman, E., & Xie, Y. (2008). Double jeopardy? The interaction of gender and race on earnings in the United States. Social Forces, 86(3), 1217–1244.

Greenwood, M. J. (2014). Migration and Economic Growth in The United States: National, Regional, and Metropolitan Perspectives. Academic Press.

Hall, T. D. (1989). Social Change in the Southwest, 1350–1880. University of Kansas Press.

Haller, W., Portes, A., & Lynch, S. M. (2011). Dreams fulfilled, dreams shattered: Determinants of segmented assimilation in the second generation. Social Forces, 89(3), 733–762.

Heathcote, J., Perri, F., & Violante, G. L. (2010). Unequal we stand: An empirical analysis of economic inequality in the United States, 1967–2006. Review of Economic Dynamics, 13(1), 15–51.

Huyser, K. R., Sakamoto, A., & Takei, I. (2010). The persistence of racial disadvantage: The socioeconomic attainments of single-race and multi-race Native Americans. Population Research and Policy Review, 29(4), 541–568.

Jiménez, T. R. (2008). Mexican immigrant replenishment and the continuing significance of ethnicity and race. American Journal of Sociology, 113(6), 1527–1567.

Jones, N., Marks, R., Ramirez, R., & Ríos-Vargas, M. (2021). 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. U.S. Census Bureau.

Joshi, P., Walters, A. N., Noelke, C., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2022). Families’ job characteristics and economic self-sufficiency: Differences by income, race-ethnicity, and nativity. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 8(5), 67–95.

Kanaiaupuni, S. M. (2000). Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces, 78(4), 1311–1347.

Kim, J., & Carter, S. D. (2016). Gender inequality in the U.S. labor market: Evidence from the American Community Survey. In M. F. Karsten (Ed.), Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in the Workplace: Emerging Issues and Enduring Challenges (pp. 59–82). Praeger.

Kim, R. Y. (2002). Ethnic differences in academic achievement between Vietnamese and Cambodian children: Cultural and structural explanations. The Sociological Quarterly, 43(2), 213–235.

Kmec, J. A. (2003). Minority job concentration and wages. Social Problems, 50(1), 38–59.

Lee, J., & Bean, F. D. (2007). Reinventing the color line: Immigration and America’s new racial/ethnic divide. Social Forces, 86(2), 561–586.

Lieberson, S. (1980). A Piece of the Pie: Blacks and White Immigrants Since 1880. University of California Press.

Lu, Y., & Huo, F. (2020). Immigration system, labor market structures of high-skilled immigrants in the United States and Canada. International Migration Review, 54(4), 1072–1103.

Lu, Y., & Li, X. (2021). Vertical education-occupation mismatch and wage inequality by race/ethnicity among highly educated U.S. workers. Social Forces, 100(2), 706–737.

Lueck, K. (2018). Socioeconomic success of Asian immigrants in the United States. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(3), 425–438.

Mandel, H., & Semyonov, M. (2014). Gender pay gap and employment sector: Sources of earnings disparities in the United States, 1970–2010. Demography, 51(5), 1597–1618.

Marrow, H. B. (2009). New immigrant destinations and the American colour line. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32(6), 1037–1057.

Masouk, N., & Junn, J. (2013). The Politics of Belonging: Race, Public Opinion, and Immigration. The University of Chicago Press.

McCall, L. (2001). Sources of racial wage inequality in metropolitan labor markets: Racial, ethnic, and gender differences. American Sociological Review, 66(4), 520–541.

McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs, 30(3), 1771-l880.

Millsap, A. (2016). State labor force changes and the need for a flexible labor market. Forbes. August 5, 2016.

Nash, J. C. (2008). Re-thinking intersectionality. Feminist Review, 89(1), 1–15.

Nawyn, S. J., & Gjokaj, L. (2014). The magnifying effect of privilege: Earnings inequalities at the intersection of gender, race, and nativity. Feminist Formations, 26(2), 85–106.

Nawyn, S. J., & Park, J. (2019). Gendered segmented assimilation: Earnings trajectories of African immigrant women and men. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 42(2), 216–234.

Neckerman, K. M., & Torche, F. (2007). Inequality: Causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 335–357.

Nee, V., & Sanders, J. M. (2001). Understanding the diversity of immigrant incorporation: A forms of capital model. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24(3), 386–411.

Obinna, D. N. (2018). Ethnicity, reception, and the growth of American immigration. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(2), 171–188.

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). (1997). Revisions to the standards for the classification of federal data on race and ethnicity. Federal Register, 62(210), 58782–58790.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2015). Racial Formation in the United States (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Ortiz, V., & Telles, E. (2012). Racial identity and racial treatment of Mexican Americans. Race and Social Problems, 4, 41–56.

Painter, M. A., II. (2013). Immigrant and native financial well-being: The roles of place of education and race/ethnicity. Social Science Research, 42(5), 1375–1389.

Painter, M. A., II., & Qian, Z. (2016). Wealth inequality among immigrants and native-born Americans: Persistent racial/ethnic inequality. Population Research and Policy Review, 35(2), 147–175.

Park, J., Nawyn, S. J., & Benetsky, M. J. (2015). Feminized intergenerational mobility without assimilation? Post-1965 U.S. immigrants and the gender revolution. Demography, 52(5), 1601–1626.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut. R.G. (2001). Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley, CA & New York, NY: University of California Press & The Russell Sage Foundation.

Portes, A., & Rivas, A. (2011). The adaptation of migrant children. Future of Children, 21(1), 219–246.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2014). Immigrant America Portrait, Updated, and Expanded (4th ed.). University of California Press.

Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Annals of the American Political and Social Sciences, 530, 74–96.

Potocky-Tripodi, M. (2003). Refugee economic adaptation: Theory, evidence, and implications for policy and practice. Journal of Social Service Research, 30(1), 63–91.

Quadlin, N. (2018). The mark of a woman’s record: Gender and academic performance in hiring. American Sociological Review, 83(2), 331–360.

Reskin, B. F. (2018). Labor Markets as Queues: A Structural Approach to Changing Occupational Sex Composition. In D. Grusky & S. Szelenyi (Eds.), Inequality: Classic Readings in Race, Class, and Gender (pp. 191–206). Routledge.

Restifo, S. J., & Mykyta, L. (2019). At a crossroads: Economic hierarchy and hardship at the intersection of race, sex, and nativity. Social Currents, 6(6), 507–533.

Roscigno, V. J. (2007). The Face of Discrimination: How Race and Gender Impact Work and Home Lives. Rowman & Littlefield.

Roscigno, V. J., Cantzler, J. M., Restifo, S. J., & Guetzkow, J. (2015). Legitimation, state repression, and the Sioux Massacre at Wounded Knee. Mobilization, 20(1), 17–40.

Ruggles, S., Flood, S., Foster, S., Goeken, R., Pacas, J., Schouweiler, M., & Sobek, M. (2021). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 11.0 . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V11.0.

Rumbaut, R. G. (2008). The coming of the second generation: Immigration and ethnic mobility in Southern California. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 620(1), 196–236.

Sakamoto, A., Goyette, K. A., & Kim, C. (2009). Socioeconomic attainments of Asian Americans. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 255–276.

Smeeding, T. M. (2005). Public policy, economic inequality, and poverty: The United States in comparative perspective. Social Science Quarterly, 86(s1), 955–983.

Stewart, Q. T., & Dixon, J. C. (2010). Is it race, immigrant status, or both? An analysis of wage disparities among men in the United States. International Migration Review, 44(1), 173–201.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2022). Alternative theories of inequality: Causes, consequences, and policies. In R. L. von Arnim & J. E. Stiglitz (Eds.), The Great Polarization: How Ideas, Power, and Policies Drive Inequality (pp. 33–100). Columbia University Press.

Stone, R. A. T., Purkayastha, B., & Berdahl, T. A. (2006). Beyond Asian American: Examining conditions and mechanisms of earnings inequality for Filipina and Asian Indian women. Sociological Perspectives, 49(2), 261–281.

Sue, S., & Okazaki, S. (1990). Asian-American educational achievements: A phenomenon in search of an explanation. American Psychologist, 45(8), 913–920.

Tolnay, S. E. (2004). The living arrangements of African American and immigrant children, 1880–2000. Journal of Family History, 29(4), 421–445.

Valdez, N. M., & Tran, V. C. (2020). Gendered context of assimilation: The female second-generation advantage among Latinos. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(9), 1709–1736.

Valdez, Z. (2006). Segmented assimilation among Mexicans in the Southwest. The Sociological Quarterly, 47(3), 397–424.

VanHeuvelen, T. (2018). Moral economies or hidden talents? A longitudinal analysis of union decline and wage inequality, 1973–2015. Social Forces, 97(2), 495–530.

Villarreal, A., & Tamborini, C. R. (2018). Immigrants’ economic assimilation: Evidence from longitudinal earnings records. American Sociological Review, 83(4), 686–715.

Weisshaar, K. (2018). From opt out to blocked out: The challenges for labor market re-entry after family-related employment lapses. American Sociological Review, 83(1), 34–60.

Weisshaar, K., & Cabello-Hutt, T. (2020). Labor force participation over the life course: The long-term effects of employment trajectories on wages and the gendered payoff to employment. Demography, 57(1), 33–60.

Wilson, G. (1997). Pathways to power: Racial differences in the determinants of job authority. Social Problems, 44(1), 38–54.

Wilson, G. (2009). Downward mobility of women from white-collar employment: Determinants and timing by race. Sociological Forum, 24(2), 382–401.

Wilson, G., Roscigno, V. J., & Huffman, M. (2015). Racial income inequality and private sector privatization. Social Problems, 62(2), 163–185.

Wursten, J., & Reich, M. (2021). Racial Inequality and Minimum Wages in Frictional Labor Markets. IRLE Working Paper No. 101–21. University of California, Berkeley.

Yun, K., Fuentes-Afflick, E., & Desai, M. M. (2012). Prevalence of chronic disease and insurance coverage among refugees in the United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14(6), 933–940.

Yuval-Davis, N. (2006). Intersectionality and feminist politics. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 13(3), 193–209.

Zhou, M. (1997). Segmented assimilation: Issues, controversies, and recent research on the new second generation. International Migration Review, 31(4), 975–1008.

Zhou, M., Lee, J., Vallejo, J. A., Tafoya-Estrada, R., & Sao Xiong, Y. (2008). Success attained, deterred, and denied: Divergent pathways to social mobility in Los Angeles’s new second generation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 620(1), 37–61.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Earlier drafts of this article were presented at the 2019 American Sociological Association Meeting, New York, NY and 2019 Population Association of America Meeting, Austin, TX.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Restifo, S.J., Ryabov, I. & Ruiz, B. Race, Gender, and Nativity in the Southwest Economy: An Intersectional Approach to Income Inequality. Popul Res Policy Rev 42, 48 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09779-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09779-x