Abstract

Some arguments include imperative clauses. For example: ‘Buy me a drink; you can’t buy me that drink unless you go to the bar; so, go to the bar!’ How should we build a logic that predicts which of these arguments are good? Because imperatives aren’t truth apt and so don’t stand in relations of truth preservation, this technical question gives rise to a foundational one: What would be the subject matter of this logic? I argue that declaratives are used to produce beliefs, imperatives are used to produce intentions, and beliefs and intentions are subject to rational requirements. An argument will strike us as valid when anyone whose mental state satisfies the premises is rationally required to satisfy the conclusion. For example, the above argument reflects the principle that it is irrational not to intend what one takes to be the necessary means to one’s intended ends. I argue that all intuitively good patterns of imperative inference can be explained using off-the-shelf formulations of our rational requirements. I then develop a formal-semantic theory embodying this view that predicts a range of data, including free-choice effects and Ross’s paradox. The resulting theory shows one way that our aspirations to rational agency can be discerned in the patterns of our speech, and is a case study in how the philosophy of language and the philosophy of action can be mutually illuminating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a defense of the idea that there are good imperative arguments, see Vranas (2010).

Some have argued that directive force is not semantically encoded in imperative clauses. One commonly given reason is that we sometimes perform non-directive speech acts using imperatives. For example, ‘have a cookie’ might be used to to invite or permit someone to have a cookie; ‘get well soon’ might be used to wish someone well; and ‘take the A train’ might be used to give instructions for going uptown. None of these speech acts would naturally be described as directives, nor need they count as failures if the addressee fails to form an intention to comply. I think that these data are compatible with my view, but an adequate explanation of why would not fit into this paper, and so will have to await another occasion. However, I will discuss “weak” uses of imperatives, such as invitations and permissions below (see in particular footnote 15). I will also briefly discuss wish uses in footnote 10. I think that instruction uses are best understood as indirect speech acts in which the speaker makes as if to issue a directive in order to indirectly communicate information about how one would comply with it, but I won’t try to defend this view here.

Charlow (2014) defends the view that declaratives denote beliefs and imperatives denote plans (which I take to be interchangable with intentions). His formal semantics is a major influence on the one that I will defend in Sect. 6. It is unclear how much of my foundational account Charlow would accept.

Some have claimed that belief that one will \(\phi\) is constitutive of intending to \(\phi\), so that it is impossible, and not merely irrational, to violate the doxastic constraint (Grice 1971; Harman 1976; Audi 1973; Anscombe 1963; Neale 2016). I follow a range of others in thinking that it is possible but irrational to violate the constraint (Bratman 1987; Broome 1999; Holton 2011).

My claims about rational requirements draws heavily on work by Bratman (1987, 1999, 2007), Broome (1999, 2013), Ferrero (2009), Holton (2008), (2011), and others. It is worth noting that even if rational requirements are mere side effects of our responsiveness to reasons, as Kolodny (2008a, 2008b) argues, or even if they are merely rough generalizations about how the pressure to be rational plays out, as Fogal (2020) argues, this does not prevent them (or the facts giving rise to them) from playing the role that I take them to play here.

Condoravdi and Lauer (2012) actually embrace this consequence, and argue that “wish” uses of imperatives (as when we tell a sick person to ‘get well soon’) are semantically basic, expressing the speaker’s preferences, with directive uses resulting only in contexts where the speaker’s preferences are understood to entail obligations for the addressee. However, most imperatives can’t be felicitously used to express mere wishes (e.g. ‘get tenure!’; ‘win the lottery!’), and so it seems likely that these uses are idiosyncratic and do not reflect semantic properties of imperatives in general (cf. Kaufmann 2019, 341n39).

I have left out some details from Holton’s example that aren’t relevant for my purposes.

A confusing-terminology warning: (i) Bratman uses ‘partial plan’ to describe a plan whose implementation details aren’t yet worked out, but this is not what Holton means by ‘partial intention’. (ii) It is common to use ‘partial belief’ to discuss credence (a.k.a. subjective probability), but this isn’t what Holton means by ‘partial belief’ (Holton 2008, §3).

One weakness of Charlow’s (2014) precursor to my view is that he gives the semantics for a disjunction, \(\Phi\) or \(\Psi\), by defining it as equivalent to \(\lnot (\lnot \Phi\) and \(\lnot \Psi )\). There are two problems with this. First, it incorrectly entails that satisfying a disjunction requires satisfying at least one of its disjuncts. Second, as Starr (2020, footnote 16) has pointed out, imperatives apparently don’t scope under negation, and so it is unclear what a relevant negated conjunction of negated imperatives is supposed to mean.

There remains the question of whether the distinction between weak and strong uses of imperatives should be understood as a semantic ambiguity or as the result of some pragmatic effect. I will offer a semantic clause for weak imperatives in Sect. 6, but one could also take strong uses as basic and think of weak uses as arising from a kind of pragmatic weakening (von Fintel and Iatridou 2017). I won’t pursue this idea here, except to say that if it is right that weak uses are derived pragmatically, then my theory predicts that imperative free-choice effects are also a pragmatic phenomenon.

For example, Charlow (2014).

On the idea that assertions in general must be answers to a contextually salient question in order to be felicitous, see Roberts (2012). My claim about conjunctions follows straightforwardly. On the idea that felicitous disjunctions must present alternative answers to a contextually salient question, see Simons (2000, §2.3.2). I will not attempt to incorporate contextual questions into the formal model that I construct in the next several sections, and so these constraints on felicity will remain informal here.

This way of modeling beliefs is originally due to Hintikka (1962). Possible-worlds models have been used to model intentions by computer scientists working in the Belief-Desire-Intention (BDI) tradition—e.g., Cohen and Levesque (1990). The most direct precursor to cognitive models are Charlow’s (2014) “representors”, although they also bear some resemblance to Starr’s (2020) “conversational states”.

They are also idealized in a second sense, which is that they oversimplify some aspects of belief and intention, such as by representing agents as believing and intending all necessary truths—a well-known issue with possible-worlds models.

We can model the state of believing that p is required for q as \(\lambda M. (B_M\cap p) \subseteq q\). This is too strong, in that it says nothing about the p happening before q. In order to capture the weaker interpretation, we would need to lift another idealization in cognitive models by adding a temporal dimension.

Here I am inspired by Weisberg’s (2007, 642) discussion of “minimalist idealizations,” which work by misrepresenting a system in a way that isolates just those features that play a crucial role in explaining the target phenomenon.

Versions of this idea have been defended by Portner (2004, 2007); Hausser (1983); Portner et al. (2019); von Fintel and Iatridou (2017); Roberts (2018), and Zanuttini et al. (2012), among others. I adopt it for two reasons. First, it gives us a clear explanation of why imperatives invariably have second-person subjects—albeit subjects that are usually unpronounced in English. (We know they’re there, and that they’re second person, because imperative subjects can bind second-person pronouns, as in ‘give yourself a pat on the back’.) On the view defended by Zanuttini et al. (2012), imperative clauses contain a functional head in their clausal structure called a ‘jussive head,’ which bears a second-person feature and binds the subject. This leads the clause as a whole to have an addressee-restricted property as its semantic value, and makes imperative subjects invariably second-person (at least in languages like English). Second, this proposal gives us some hope of explaining why imperatives fail to embed in many constructions that embed declaratives (for example, in belief ascriptions). A simple version of this explanation would appeal to the idea that many environments that can compose with proposition-denoting expressions can’t embed property-denoting expressions. Portner et al. (2019) defend a more elaborate explanation that appeals to expressive features of imperative subjects that vary cross-linguistically in ways that appear to parallel the cross-linguistic embeddability of imperatives.

In these respects, my semantic theory is modeled on that of Charlow (2014), who pioneered the idea of modeling clausal semantic values as properties of a model that represents an agent’s beliefs and plans.

Imperatives also embed under attitude verbs in some languages, and probably don’t contribute properties of cognitive models when they do. Portner et al. (2019) argue that they typically contribute addressee-directed properties. (But see Kaufmann (2019) for an opposing view on which they contribute modal propositions.)

I have built more than usual into the semantics of disjunction. First, I take it to be a semantic matter that a speaker who utters a disjunction rules out alternatives other than the disjuncts—what Zimmermann (2000, §4.1) calls ‘exhaustivity’. This is also a feature of classical disjunction, but Zimmermann (2000) and Geurts (2005) conclude that it does not belong in the semantics of ‘or’, arguing that it is instead contributed by falling intonation. Second, and this time with Zimmerman and Geurts but contrary to classical disjunction, I have taken it to be a semantic matter that a speaker who utters a disjunction treats both disjuncts as live alternatives—what Zimmermann (2000, §4.1) calls “genuineness.” Several authors have argued that this feature of disjunctive utterances is an implicature rather than part of the meaning of ‘or’ (Grice 1989, 45; Simons 2005, §5.3.1; Alonso-Ovalle 2006, §4.4). I am unconvinced, but I won’t argue the point here. Instead I will point out that it is easy to tweak (49) to remove exhaustivity or genuineness. For example, the following clause removes both:

- (49)\(^*\):

-

disjunction (without genuineness or exhaustivity)

$$\llbracket \Phi \text { or } \Psi \rrbracket = \lambda M_\Downarrow \llbracket \Phi \rrbracket (M_\Downarrow ) \vee \llbracket \Psi \rrbracket (M_\Downarrow ).$$

My account of Ross’s paradox and imperative free choice both depend on the assumption that ‘or’ has genuineness built into its semantics, and so switching to (49)\(^*\) would necessitate giving a pragmatic explanation of these phenomena. We could posit a quantity implicature: A speaker who leaves two options open could have closed one off, but chose not to. Since leaving one option out would have been more informative, the speaker must have had a reason not to. The best explanation is that they intended both options to be treated as genuine. (For more sophisticated pragmatic explanations, see Alonso-Ovalle (2005, 2006); Fox (2007); Geurts (2009).)

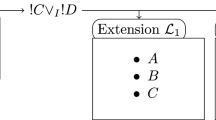

I have represented the disjunctions in both Ross’s paradox and imperative free choice as taking wide scope over the mood markers, as in \(\ulcorner !\phi\) or \(!\psi \urcorner\). A reason to think that this is at least sometimes the right LF is that that mixed imperative–declarative disjunctions pattern with disjunctions of imperatives when it comes to both Ross’s paradox and free choice, and there is no single mood marker that can take wide scope in mixed disjunctions. However, VP disjunctions would seem to scope under mood markers, as in ‘Post or burn the letter’, and so we should probably also block the Ross inference and validate free choice for the LF \(\ulcorner !(\phi\) or \(\psi )\urcorner\). Moreover, we also find versions of Ross’s paradox and free choice that involve indefinites, which presumably scope under mood (e.g. Ross: ‘Help yourself to that cookie on the left’ \(\not \vDash\) ‘Help yourself to a cookie’).

Here is one way to extend my semantics to make these predictions. First, we model disjunction and indefinites as alternative-introducing expressions, and we take sentence radicals to denote sets of alternatives rather than single propositions or properties (Alonso-Ovalle 2006; Simons 2005; Aloni 2003, 2007; Charlow 2019). For example, the content of ‘have coffee or tea’ would be a set that includes the property of having coffee and the property of having tea. Second, we adjust our semantics for mood markers so that they take alternative sets rather than propositions or properties as inputs. For example, here is a revised clause for !:

- (43)\(^*\):

-

strong imperative alternative semantics \(\llbracket !\rrbracket ^c\) = \(\lambda P\) . \(\lambda M\) . \((\forall f \in P)(\exists \langle \beta ,\iota \rangle \in \Omega ^A_M)(\iota \subseteq f(a_c)) \wedge (\forall \langle \beta ,\iota \rangle \in \Omega ^A_M)(\exists f \in P)(\iota \subseteq f(a_c))\)

This clause would make \(!(\phi\) or \(\psi )\) equivalent to \(!\phi\) or \(!\psi\), and could generalize to indefinites as well as disjunction. Of course, this is just a rough sketch of an idea that would need much more work.

References

Aloni, M. (2003). Free choice in modal contexts. In M. Weisgerber (Ed.), Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 7, chapter 2, pp. 25–37. University of Konstanz.

Aloni, M. (2007). Free choice, modals, and imperatives. Natural Language Semantics, 15, 65–94.

Alonso-Ovalle, L. (2005). Distributing the disjuncts over the modal space. In L. Bateman, C. Ussery (Ed.), Proceedings of the 35th North East Linguistics Society Conference, pp 75–86. GSLA, Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Alonso-Ovalle, L. (2006). Disjunction in Alternative Semantics. Amherst: University of Massachusetts (PhD thesis).

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1963). Intention (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Audi, R. (1973). Intending. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 387–403.

Barker, C. (2012). Imperatives denote actions. In A. A. Guevara, A. Chernilovskaya, R. Nouwen (Ed.), Proceedings of Sinn and Bedeutung 16, chapter 5. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Bratman, M. (1987). Intention, plans, and practical reason. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bratman, M. (1992). Shared cooperative activity. The Philosophical Review, 101(2), 327–341.

Bratman, M. (1999). Faces of Intention: Selected Essays on Intention and Agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bratman, M. (2007). Structures of Agency: Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bratman, M. (2014). Shared Agency: A Planning Theory of Acting Together. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Broome, J. (1999). Normative requirements. Ratio, XI, I(4), 398–419.

Broome, J. (2013). Rationality Through Reasoning. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Charlow, N. (2014). Logic and semantics for imperatives. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 43, 617–664.

Charlow, N. (2018). Clause-type, force, and normative judgment in the semantics of imperatives. In D. Fogal, D. Harris, & M. Moss (Eds.), New Work on Speech Acts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Charlow, S. (2019). The scope of alternatives: Indefiniteness and islands. Linguistics and Philosophy, 43(4), 427–472.

Chisholm, R. (1963). Contrary-to-duty imperatives and deontic logic. Analysis, 24(2), 33–36.

Cohen, P. R., & Levesque, H. J. (1990). Intention is choice with commitment. Artificial Intelligence, 42, 213–261.

Condoravdi, C., & Lauer, S. (2012). Imperatives: Meaning and illocutionary force. In C. Pinõn, (Ed.), Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 9: Papers From the Colloque de Syntaxe et Sémantique à Paris 2011, pp 37–58.

Culicover, P. W., & Jackendoff, R. (1997). Semantic subordination despite syntactic coordination. Linguistic Inquiry, 28(2), 195–217.

Davidson, D. (1979). Moods and performances. In A. Margalit (Ed.), Meaning and Use (pp. 9–20). Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Ferrero, L. (2009). Conditional intentions. Noûs, 43(4), 700–741.

von Fintel, K., & Iatridou, S. (2017). A modest proposal for the meaning of imperatives. In A. Arregui, M. Rivero, & A. P. Salanova (Eds.), Modality Across Semantic Categories, chapter 13 (pp. 288–319). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fogal, D. (2020). Rational requirements and the primacy of pressure. Mind. (forthcoming).

Fox, D. (2007). Free choice disjunction and the theory of scalar implicatures. In U. Sauerland & P. Stateva (Eds.), Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics (pp. 71–120). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Geurts, B. (2005). Entertaining alternatives: Disjunctions as modals. Natural Language Semantics, 13, 383–410.

Geurts, B. (2009). Scalar implicature and local pragmatics. Mind and Language, 24, 51–79.

Grice, H. P. (1968). Utterers meaning, sentence-meaning, and word-meaning. Foundations of Language, 4(3), 225–242.

Grice, H. P. (1969). Utterers meaning and intention. The Philosophical Review, 78(2), 147–177.

Grice, H. P. (1971). Intention and uncertainty. Proceedings of the British Academy, 57, 263–279.

Grice, P. (1989). Studies in the Way of Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Harman, G. (1976). Practical reasoning. The Review of Metaphysics, 29, 431–463.

Harman, G. (1986). Change in View: Principles of Reasoning. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hausser, R. (1980). Surface compositionality and the semantics of mood. In J. Searle, F. Kiefer, & M. Bierwisch (Eds.), Speech Act Theory and Pragmatics (pp. 71–96). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Hausser, R. (1983). The syntax and semantics of English mood. In F. Kiefer (Ed.), Questions and Answers (pp. 97–158). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Hill, T. E. (1973). The hypothetical imperative. The Philosophical Review, 82(4), 429–450.

Hintikka, J. (1962). Knowledge and Belief: An Introduction to the Logic of the Two Notions. New York: Cornell University Press.

Holton, R. (2008). Partial belief, partial intention. Mind, 117(465), 27–58.

Holton, R. (2011). Willing, Wanting, Waiting. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaufmann, S., & Schwager, M. (2009). A unified analysis of conditional imperatives. In Cormany, E., Ito, S., Lutz, D., (Ed.), Proceedings of SALT 19, pp 239–256. Columbus: Ohio State University.

Kaufmann, M. (2012). Interpreting Imperatives. Dordrecht: Springer.

Kaufmann, M. (2019). Fine-tuning natural language imperatives. Journal of Logic and Computation, 29(3), 321–348.

Keshet, E. (2012). Focus on conditional conjunction. Journal of Semantics, 30(2), 211–256.

Keshet, E., & Medeiros, D. J. (2019). Imperatives under coordination. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 37, 869–914.

Klinedinst, N., & Rothschild, D. (2012). Connectives without truth tables. Natural Language Semantics, 20, 137–175.

Kolodny, N. (2008a). The myth of practical consistency. European Journal of Philosophy, 16(3), 366–402.

Kolodny, N. (2008b). Why be disposed to be coherent? Ethics, 118, 437–463.

Lewis, D. K. (1970). General semantics. Synthese, 22(1/2), 18–67.

Neale, S. (2016). Silent reference. In G. Ostertag (Ed.), Meanings and Other Things: Essays in Honor of Stephen Schiffer (pp. 229–342). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Portner, P. (2004). The semantics of imperatives within a theory of clause-types. In Watanabe, K., Young, R., (Ed.), Proceedings of SALT 14. Washington: CLC Publications.

Portner, P., Pak, M., & Zanuttini, R. (2019). The speaker-addressee relation in imperatives. In Bondarenko, T., Davis, C., Colley, J., Privoznov, D., (Ed.), MIT Workinng Papers in Linguistics 90: Proceedings of the 14th Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics (WAFL14). MIT Workinng Papers in Linguistics, Cambridge.

Portner, P. (2007). Imperatives and modals. Natural Language Semantics, 15, 351–383.

Portner, P. (2012). Permission and choice. In G. Grewendorf & T. Zimmermann (Eds.), Discourse and Grammar: From Sentence Types to Lexical Categories (pp. 43–68). Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Roberts, C. (2012). Information structure in discourse: Toward an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics and Pragmatics, 5, 1–69.

Roberts, C. (2018). Speech acts in discourse context. In D. Fogal, D. Harris, & M. Moss (Eds.), New Work on Speech Acts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ross, A. (1941). Imperatives and logic. Theoria, 25(7), 53–71.

Sadock, J. (1974). Toward a Linguistic Theory of Speech Acts. New York: Academic Press.

Schroeder, M. (2004). The scope of instrumental reason. Philosophical Perspectives, 18, 337–364.

Searle, J. (1969). Speech Acts. London: Cambridge University Press.

Simons, M. (2000). Issues in the Semantics and Pragmatics of Disjunction. New York: Garland.

Simons, M. (2005). Dividing things up: The semantics of or and the modal/or interaction. Natural Language Semantics, 13, 271–316.

Starr, W. B. (2010). Conditionals, Meaning and Mood. PhD thesis, Rutgers University.

Starr, W. (2020). A preference semantics for imperatives. Semantics and Pragmatics, Early Access

Starr, W. B. (2014). Mood, force, and truth. Protosociology, 31, 160–180.

Stokke, A. (2014). Insincerity. Noûs, 48(3), 496–520.

Vranas, P. (2010). In defense of imperative inference. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 39, 59–71.

Weisberg, M. (2007). Three kinds of idealization. Journal of Philosophy, 104(12), 639–659.

Zanuttini, R., Pak, M., & Portner, P. (2012). A syntactic analysis of interpretive restrictions on imperative, promissive, and exhortative subjects. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 30(4), 1231–1274.

Zimmermann, T. E. (2000). Free choice disjunction and epistemic possibility. Natural Language Semantics, 8, 255–290.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I have received helpful feedback on earlier versions of this paper from Chris Barker, Bob Beddor, Justin Bledin, Lucas Champollion, Nate Charlow, Josh Dever, Kai von Fintel, Daniel Fogal, Magdalena Kaufmann, Ernie Lepore, Stephen Neale, Paul Portner, Jim Pryor, Craige Roberts, Will Starr, Elmar Unnsteinsson, Alex Worsnip, Seth Yalcin, several anonymous referees, and audiences at the University of Pennsylvania, Hunter College, the New York Philosophy of Language Workshop, NYU, the Institute of Philosophy in London, PhLiP 4 in Tarrytown, and the Chapel Hill Normativity Workshop.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, D.W. Imperative inference and practical rationality. Philos Stud 179, 1065–1090 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-021-01687-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-021-01687-0