Abstract

Background

Pharmacy practice research often focuses on the design, implementation and evaluation of pharmacy services and interventions. The use of behavioural theory in intervention research allows understanding of interventions’ mechanisms of action and are more likely to result in effective and sustained interventions.

Aim

To collate, summarise and categorise the reported behavioural frameworks, models and theories used in pharmacy practice research.

Method

PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science and EBSCO (CINAHL PLUS, British Education index, ERIC) were systematically searched to capture all pharmacy practice articles that had reported the use of behavioural frameworks, theories, or models since inception of the database. Results were filtered to include articles published in English in pharmacy practice journals. Full-text screening and data extraction were independently performed by two reviewers. A narrative synthesis of the data was adopted. Studies were reviewed for alignment to the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) framework to identify in which phase(s) of the research that the theory/model/framework had been employed.

Results

Fifty articles met the inclusion criteria; a trend indicating an increasing frequency of behavioural theory/frameworks/models within pharmacy practice research was identified; the most frequently reported were Theory of Planned Behaviour and Theoretical Domains Framework. Few studies provided explicit and comprehensive justification for adopting a specific theory/model/framework and description of how it underpinned the research was lacking. The majority were investigations exploring determinants of behaviours, or facilitators and barriers to implementing or delivering a wide range of pharmacy services and initiatives within a variety of clinical settings (aligned to Phase 1 UK MRC framework).

Conclusion

This review serves as a useful resource for future researchers to inform their investigations. Greater emphasis to adopt a systematic approach in the reporting of the use of behavioural theories/models/frameworks will benefit pharmacy practice research and will support researchers in utilizing behavioural theories/models/framework in aspects of pharmacy practice research beyond intervention development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact statements

-

There is trend indicating the increased adoption of behavioural theories/models/frameworks to underpin pharmacy practice research. However, identified articles are limited to predominantly investigations of intervention development. Therefore, we recommend that future research utilize behavioural theories/models/frameworks in phase 2–4 of the UK MRC framework.

-

Pharmacy practice research will benefit from adopting a systematic approach in the reporting of the use of behavioural theories/models/frameworks.

-

Inconsistent reporting of using theories/models/frameworks in pharmacy practice research has been noted among included studies, thus we suggest establishing a specific reporting checklist which could enhance the comprehensiveness of reporting and subsequently enable practitioners, policymakers, and other stakeholders to develop theory-informed interventions to promote patient safety and enhance the pharmacy practice.

Introduction

Pharmacy practice is described as a “scientific discipline that studies the different aspects of the practice of pharmacy, and its impact on health care systems, medicine use, and patient care” [1]. It focuses on improving health outcomes of individuals and populations as well as improving access, safety, and breadth of available services [2]. Pharmacy practice research therefore embraces both clinical pharmacy and social pharmacy elements [3]. While the terms ‘clinical pharmacy’ and ‘pharmaceutical care’ have been instrumental in initiating a shift towards more person-centered approach, its distinct research scope has expanded globally to encompass clinical, behavioural, economic, and humanistic implications of the practice of pharmacy [1, 4].

A discussion paper by Nørgaard et al. in 2000 argued the need for theory-based pharmacy practice research [5]. Pharmacy practice research often focuses on the design, implementation and evaluation of pharmacy services and interventions aimed at optimising patient safety [6]. These pharmacy services all contain an element of behavioural change for the pharmacist, the patient or the wider public, to produce the desired target outcome [7]. To assist researchers, the UK MRC Framework, first published in 2000, provides a structured approach to develop, evaluate, and implement such complex interventions using a range of qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method research approaches to help researchers make appropriate methodological and practical choices [8]. The UK MRC framework recognizes four phases of complex intervention research: 1. Development or identification of an intervention; 2. Assessment of feasibility of the intervention and evaluation design, 3. Evaluation of the intervention, 4. Impactful implementation [8]. They advocate underpinning theory at each phase.

Underpinning studies with behavioural theories/models/frameworks, has the potential to assist researchers to better understand the behaviour change process and guide the refinement of the intervention [9].

Many behavioural change theories/models/frameworks exist in the application of healthcare research. As a result, identifying the most suitable behavioural theory/model/framework to adequately address the desired research question is difficult and requires the appropriate expertise and a comprehensive understanding of available theories, models and frameworks. This starts with a correct understanding of the terminologies used.

Theories, models, and frameworks explained

Although there are many explanations of theories, models, and frameworks, there are many similarities and overlapping concepts. One common definition of ‘theory’ is “…an account of the world, which goes beyond what we can see and measure. It embraces a set of inter-related definitions and relationships that organises our concepts and understanding of the empirical world in a systematic way” [10]. A good theory provides a clear explanation of how and why specific relationships lead to specific events [11].

A model is often a simplified representation of a complex system, designed to focus on a specific question [12]. Models can be described as theories with a more narrowly defined scope of explanation; a model is descriptive, whereas a theory is explanatory as well as descriptive [13]. Models need not always be completely accurate representations of reality to be of value [14]. According to Creswell, a complex research theory may be presented as a simplified model so “that the reader can visualize the interconnections of variables” [15]. A conceptual framework on the other hand provides a set of “big” or “grand” concepts or theories [16]; frameworks do not provide explanations; they categorise empirical phenomena [13].

Supplementary Material 1 aims to provide a brief overview of some of the behavioural theories/models/frameworks commonly used in healthcare research. Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory proposes that people are driven by external factors rather than inner forces [17]; the Theory of Planned Behaviour is dependent on one’s intention to perform the behavior [18], while the Transtheoretical Model proposes change as a process of six stages [19]. The COM-B model allows the mapping of the capability, opportunity and motivation of any person to determine the likelihood of a behaviour to occur [20]. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), an “integrative framework developed from a synthesis of psychological theories as a vehicle to help apply theoretical approach to intervention aimed at behavioural change”, is useful to better understand implementation problems of health initiatives which are often heterogeneous and complex [21].

The recently articulated Granada statements published in a number of clinical and social pharmacy practice journals aspire to improve the quality of publications and advance the paradigms of related pharmacy practice research [3]. It is therefore timely to review the use of behavioural theories/models/frameworks in pharmacy practice research to date to inform future studies.

Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to collate, summarise and categorise the reported behavioural theories/models/frameworks used in pharmacy practice research.

Method

Protocol and registration

This scoping review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [22]. The protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework database (Registration number: qfw6d).

Eligibility criteria

The review included studies published in pharmacy practice journals. A list of the 33 peer-reviewed pharmacy practice journals indexed in PubMed, was compiled based on Mendes et al.’s study, which classified 285 pharmacy journals into six clusters including ‘Pharmacy Practice’ (67 journals, 33 indexed in PubMed) [23]. (Supplementary Material 2).

Databases were searched since inception to capture all pharmacy practice articles that had reported the use of any behavioural theories/models/frameworks. If it was not immediately clear whether the theory/model/framework was eligible for inclusion, consensus was sought between two research team members (ZN and LN) with reference made to the research that described the theory/model/framework development, if necessary. Consultation with the wider research group was made if consensus could not be reached.

Only studies published in English were included. All primary research study designs and reviews were considered. Letters, commentaries, perspectives, and editorials were excluded, as were studies that developed and/or validated theories.

Information sources and search strategy

The following electronic databases were independently searched by two authors (ZN, LN) on 30 May 2022; PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science and EBSCO (CINAHL PLUS, British Education index, ERIC). The following search string was used for PubMed and adapted for the other databases: (pharmacy(MeSH) [Title/Abstract]) AND ((theor*[Title/Abstract]) OR (framework [Title/Abstract])). Search strategies are provided in Supplementary Material 3.

Articles were exported to Rayyan QCRI® [24] and duplicates removed. Filters were applied to include articles published in the aforementioned 33 Pharmacy Practice Journals. Title/abstract screening and full-text screening were independently performed by two reviewers (ZN, LN). In cases of disagreements a third reviewer was consulted. Reference lists of included studies were manually checked.

Data charting process and data items

The authors designed a data extraction tool based on the inclusion criteria and focused on key information required to comprehensively answer the research question and piloted it with 3 included articles. The following data were extracted: country, year of publication, study type and design, objective of study, outcomes measured, and the theory/model/framework reported in the study. Further details regarding how the theories/models/frameworks were used in study design including the research phase, context, and purpose of its use, were also extracted. Six reviewers were involved in the data extraction process and data extraction of each article was performed independently by two reviewers. In cases of disagreements a third reviewer was consulted.

Synthesis of results

Data were summarized quantitatively and qualitatively in relation to the research aim. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the number of studies by year published, country, and research design. Summary statistics were used to report the frequency of use, rationale for use, and how each theory/model/framework was used in the reported studies. A narrative approach was adopted to synthesise the findings. Narrative synthesis has been defined as “an approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and texts to summarize and explain the findings of the synthesis” [25].

Further, studies reporting a complex intervention as defined by the UK MRC, as those with several interacting components, or if they are dependent on the behaviour of those delivering and receiving the intervention [8], were reviewed to identify in which phase(s) of complex intervention research the theory/model/framework had been employed.

Results

Search results

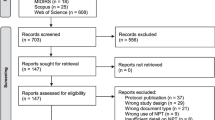

Fifty articles met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1 presents the PRISMA Flow Diagram). A summary of the characteristics of included studies is presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Material 4 provides full details of the included studies.

Study characteristics

Included studies were published between 2006 and 2022, with a marked rise after 2014 (Fig. 2). Most studies were conducted in North America (n = 21) and in community pharmacies (n = 30). Study subjects included pharmacy workforce (n = 31), patients (n = 12), multiple stakeholders (n = 5), and physicians (n = 1) (Table 1).

Twenty studies were qualitative (primarily individual interviews), eighteen cross-sectional surveys and nine mixed-methods. Only one systematic review related to pharmacy practice reported utilizing a theory for data synthesis [26]. Tables 2, 3, 4 present details describing the aim of the included studies; the majority of the studies were investigations of pharmacy complex interventions, as defined by the UK MRC framework. These included investigations to explore pharmacists’ involvement in various initiatives such as medicines optimization services [27], immunization clinics [28], pharmacist prescribing [29], falls prevention [30], medicines management services [31,32,33,34,35], and pharmacogenomics testing [36, 37].

Theories, models, frameworks used

Tables 2, 3, 4 present the data pertaining to how theories/models/frameworks were used in the included studies. The majority (n = 39) of studies used a single theory/model/framework, most commonly the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (n = 18), followed by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (n = 11). In studies using a combination of multiple theories/models/frameworks; the most frequent combination was TDF with the Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Behaviour (COM-B) model.

Justification for theories/models/frameworks selected

Multiple justifications were reported for the use of theories/models/frameworks however, reporting was inconsistent, for example multiple studies simply mentioned that the theory/model/framework guided the development of the data collection tool [32, 37,38,39,40,41,42]. Beyond this, 14 studies provided a description of the theory/model/framework constructs and/or assumptions but without connecting it to the research question [28, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Nine studies provided the justification that the theory/model/framework had been used previously in similar research or within the same field [27, 30, 33, 56,57,58,59,60,61]. Only seven studies connected the theory/model/framework with the research question of the study [26, 29, 31, 34, 62,63,64]. Other reasons provided included the potential/predicted benefits the theory/model/framework might have on the findings (n = 3) [65,66,67]; recommendation from leaders in the field (n = 2) [68, 69]; and the absence of theory-informed studies in the existing body of literature (n = 2) [70, 71].

Studies that combined multiple theories/models/frameworks cited their potential synergies as the chief driver for their combined use (n = 3) [35, 36, 72] however six studies did not provide a rationale for the combination [37, 41, 42, 73,74,75].

How theories/models/frameworks were used

The use of most theories/models/frameworks (n = 31) aligned to Phase 1 of the MRC framework; to explore determinants of behaviours, or facilitators and barriers to implementing or delivering new pharmacy services. Eighteen of these studies proceeded to identify theoretical domains that should be targeted in future interventions aimed at behavioural change. Three studies [35, 54, 55] aligned to Phase 2 of the MRC framework where the theory/model/framework was used in assessing intervention feasibility. However, there was a lack of detail to determine how the theory underpinned this assessment. Studies to evaluate an intervention and to assess the impact of an intervention (Phase 3 and 4 of the MRC framework) were not identified in this review. Most theories/models/frameworks were used to inform the item development of the data collection tool (n = 24) followed by guiding data analysis (n = 17). A large number of studies used theories (n = 20) in multiple aspects of the research, in most cases to inform the data collection tool then in the subsequent data analysis and interpretation. An example includes a study that used TPB in constructing interview questions to examine the barriers and facilitators reported by community pharmacists when reconciling medications for patients recently discharged from hospital. The subsequent analysis generated themes organized based on the TPB constucts [43].

The following sections provide descriptions specific to how each of the most common theories/models/frameworks were utilized in the included studies.

Theory of planned behaviour (TPB)

TPB was used in 21 studies (Table 2 provides a summary of how TPB was used in 18 of these studies, in the other three studies TPB was used alongside a second theory/model/framework, details of studies which combined multiple theories/models/frameworks can be found in Table 4). Of the 18 studies, 15 were conducted with pharmacy professionals, in the most part to investigate behavioural influences to either implement or deliver pharmacy service initiatives (examples include vaccination services, medication therapy management services, cardiovascular support) or specific aspects of pharmaceutical care (examples included medication counselling, clinical decision making, ethical dilemmas). Three studies were conducted with patients, their focus was to understand patient behaviours in seeking pharmacy services. Although not explicitly mentioned in the majority of reports, the intervention studies aligned to Phase 1 of the UK MRC framework. TPB was used to guide the design of the data collection tool in majority of studies and less frequently to guide the analysis and interpretation of the collected data.

Theoretical domains framework (TDF)

TDF was used in 15 studies (Table 3 provides a summary of how TDF was used in 11 of these studies, in the other 4 studies TDF was used alongside a second theory/model/framework, details of these studies are presented in Table 4). Eight of the 11 studies were conducted with pharmacy professionals, in the most part to identify facilitators and barriers to either implement or deliver pharmacy service initiatives (examples include independent prescribing and immunization clinics) or specific aspects of pharmaceutical care (for example medication counselling). Thirteen studies aligned to Phase 1 of the UK MRC framework, the two other studies [54, 55] were research articles presenting data from the same project which aimed to assess the feasibility of delivering extended pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies in Australia.

Capability, opportunity, and motivation behaviour (COM-B) model

COM-B was used in 8 studies (Table 4 provides a summary of how COM-B was used in 3 of these studies, in the other 5 studies COM-B was used alongside another theory/model/framework, details of which are also presented in Table 4). All studies that used COM-B were conducted with community pharmacists to explore behavioural determinants to implement pharmacy services initiatives (these included a fall prevention service, extended pharmaceutical care services, and an asthma management service) and aligned to Phase 1 of the MRC framework. In all studies COM-B was used exclusively in the data analysis.

Health belief model (HBM)

HBM was used in 5 studies (Table 4 provides a summary of how HBM was used in 2 of these studies; in the other 3 studies HBM was used alongside another theory/model/framework, details of which are also presented in Table 4). All studies that used HBM were conducted with patients to explore behavioural determinants and predict behaviours. The studies aligned to Phase 1 of the UK MRC framework. In all studies, HBM was used for questionnaire development.

Studies that used multiple theories/models/frameworks

Other than studies utilizing TDF, which is a comprehensive framework derived from 33 psychological theories and 128 theoretical constructs [21], there were nine studies that combined multiple theories/models/frameworks. (Table 4). All studies that combined multiple theories were conducted with pharmacy professionals except for one with physicians investigating a substance misuse treatment service [72]. The primary purpose for conducting these studies was to explore behavioural determinants to implement pharmacy-based services. However, one study that described a service to treat non-prescription medication dependence used TDF and COM-B to establish the physicians’ behaviours that should be targeted in an intervention [72]. These studies aligned to Phase 1 of the UK MRC framework.

Other theories/models/frameworks

Thirteen other behavioural theories/models/frameworks were adopted in the included studies, seven were used alone and six were combined with one of the aforementioned theories/models/frameworks. The justification and purpose for use of these theories/models/frameworks was inconsistently described. For instance, the Model of Communicative Proficiency (MCP) was used in a study to frame the findings but there was no consideration of its integration into the study methodology [60]. Exceptions to this were (n = 3) using the Andersen Behavioural Model [64], Explanatory Models of Illness (EMI) [41], and Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-Metcalfe Model of Transformational Leadership [26]. The use of these theories/models/frameworks were thoroughly described and were incorporated in the design, analysis, and results synthesis and interpretation. In these studies theories were used to identify the determinants of behaviour to target in future interventions.

Reported benefits and challenges of using a theory/model/framework

Multiple studies described the benefits of using a theory/model/framework. Most frequently mentioned was the use of theory facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation compared to existing similar interventions; and secondly, the use of theory elucidated specific psychosocial factors influencing health-related behaviours and provided avenues for future research into targeted intervention development and relevant policy to improve practice or enhance patient safety. In contrast, the challenges authors faced in using theory/model/framework were rarely reported in the manuscript.

Discussion

Summary of key findings

This study identified the increasing trend to adopt the use of behavioural theories/models/frameworks within pharmacy practice research. The most utilized behavioural theories reported in pharmacy practice studies were the most established: Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB); Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF): Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Behaviour (COM-B) model; and the Health Belief Model (HBM). These findings are consistent with reviews conducted in other health domains [76,77,78]. Few studies provided explicit and comprehensive justification for adopting a specific theory/model/framework.

The majority of the included studies were investigations exploring determinants of behaviours, or facilitators and barriers to implementing or delivering a wide range of pharmacy services and initiatives within a variety of clinical settings. In reviewing the use of behavioural theories/models/frameworks against the four phases of complex intervention research proposed in the UK MRC framework, it was determined that most studies were focused on developing an intervention within a pharmacy setting (Phase 1), very few studies aligned to Phases 2–4 of the UK MRC framework.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review was conducted through the application of rigorous and transparent processes [22, 79] and to the best knowledge of the authors, is the first review that reports the use of behavioural theories/models/frameworks in pharmacy practice research. One limitation is that the review was restricted to articles published in the English language only, and articles published in 33 ‘Pharmacy Practice’ journals hence relevant publications in other languages, and in other pharmacy and non-pharmacy journals were not included. Also, investigating the gaps in the theories/models/frameworks that have been applied to pharmacy practice research fell outside the scope of this review, but the authors agree that this would be a worthwhile follow-up study.

Interpretation of findings

The majority of the included studies reported on interventions within pharmacy practice. Whilst there were many studies investigating determinants of behaviours, or facilitators and barriers to implementing new services (phase 1 of the MRC framework); there were substantially fewer studies reporting on the subsequent phases of the MRC framework. There is evidence to suggest that studies of intervention feasibility, evaluation and implementation are frequently published in journals other than pharmacy practice journals. For example a 2020 systematic review of interventions using health behaviour theories to improve medication adherence among patients with hypertension, included 11 studies, none of which were published in pharmacy practice journals [80]. The same finding was found from a 2022 systematic review to determine the utilization of the transtheoretical model of change, to predict or improve medication adherence in patients with chronic conditions [81]. Although, it is possible that publishing in non-pharmacy practice journals may enhance the visibility of the research, it means that pharmacy practice journals do not benefit from the potential impact of this research. Furthermore, the Granada statements encourage researchers to prioritise pharmacy practice and social pharmacy journals for some of their “best” work with the aim to strengthen the discipline of pharmacy practice research [3].

The use of a behavioural theory/model/framework to underpin data collection tools and data analysis in the included studies, was reported to elicit greater insight of behavioural determinants compared to existing literature that had not adopted this approach. This broader assessment was often claimed to have helped in identifying potentially unknown behavioural influences which can be targeted in the design of interventions. However, beyond describing how theory was used to inform questionnaire-design, studies lacked explicit detail of how the theory was used to underpin data analysis and interpret study findings. It is plausible, as suggested elsewhere in the literature, that word limits imposed by journals may restrict the provision of information on theoretical underpinning [82]. However, the lack of detail included meant that it was often difficult to determine what theoretical components and strategies were associated with the success or challenges of the intervention. Thus, we recommend the inclusion of further detail relating to theoretical underpinnings and expected causal mechanisms of behavioural change prospectively, and evaluation of these mechanisms to better understand what strategies are effective. This would facilitate evidence synthesis, prevent research duplication and enhance transferability of study findings [83, 84].

Moreover, since it is well-established that the use of theory in intervention research allows understanding of interventions’ mechanisms of action and are more likely to result in effective and sustained interventions [83, 85], greater consistency in describing the rationale for theory selection is warranted, with recognition that different theories are more applicable to different study settings. Selecting the most appropriate theory from amongst the wide range of options, is likely to be perplexing for researchers [86, 87], thus, guidelines to direct researchers in this regard may also serve as a useful resource. The use of checklists such as the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR), which includes an item to describe any theory used in studies when describing an intervention, has been developed to improve the completeness of reporting, and ultimately the replicability, of interventions [88]. Also authors may consider the use of a tool recently developed by Michie and Prestwich, the Theory Coding Scheme(TCS), which assesses the degree to which an intervention uses theory to guide intervention design, implementation and evaluation [89]. This tool includes 10 specific coding criteria, which range from noting whether a theory was mentioned in the introduction of a journal article to whether the findings of the study were discussed in a theoretical context. This tool may serve as a useful framework for authors to improve the use of theory and act as a blueprint for the design and reporting of intervention studies.

Further work

With the growing use of behavioural theory in pharmacy practice research, studies to ascertain whether theories/models/frameworks are being used correctly are warranted. For example, constructs may be misinterpreted or poorly measured which may result in inappropriate analysis. Such studies will help to provide further guidance for researchers.

Furthermore, this review has highlighted the inconsistent reporting of using theories/models/frameworks in pharmacy practice research, thus suggesting potential advantage to establish a specific reporting checklist.

Finally, this review did not elicit the challenges researchers face in using behavioural theory to underpin their studies, further investigations are necessary to explore these issues.

Conclusion

Behavioural theory/models/frameworks are increasingly being adopted to underpin pharmacy practice research across a variety of research designs and frequently in studies of initial investigations of complex interventions within various settings. The findings from this review indicate the need for more thorough reporting in regards to the rationale for the selection of a specific behavioural theory/model/framework; details of its application in underpinning the research; and the challenges and limitations encountered. Clearer reporting will aid in determining how best to use behavioural theory/models/frameworks in pharmacy practice research. Furthermore, studies adopting behavioural theories/models/frameworks in the latter stages of interventional research (feasibility testing, evaluation and implementation) published in pharmacy practice journals will help to further strengthen the field.

References

Garcia-Cardenas V, Rossing CV, Fernandez-Llimos F, et al. Pharmacy practice research - a call to action. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(11):1602–8.

Wiedenmayer K, Summers RS, Mackie CA, et al. Developing pharmacy practice: a focus on patient care: handbook. World Health Organization; 2006.

Fernandez-Llimos F, Desselle S, Stewart D, et al. Improving the quality of publications in and advancing the paradigms of clinical and social pharmacy practice research: the Granada statements. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45:285-92.

Dreischulte T, van den Bemt B, Steurbaut S. European Society of Clinical Pharmacy definition of the term clinical pharmacy and its relationship to pharmaceutical care: a position paper. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44(4):837–42.

Nosrgaard LS, Morgall JM, Bissell P. Arguments for theory-based pharmacy practice research. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;8(2):77–81.

Hemenway A, Meyer-Junco L, Zobeck B, et al. Utilizing social and behavioral change methods in clinical pharmacy initiatives. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022;5(4):450-8.

Jamil N, Zainal ZA, Alias SH, et al. A systematic review of behaviour change techniques in pharmacist-delivered self-management interventions towards patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2023;19(8):1131–45.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337: a1655.

Michie S, Campbell R, Brown J, et al. ABC of theories of behaviour change. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Scott J, Marshall G. A dictionary of sociology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Wacker JG. A definition of theory: research guidelines for different theory-building research methods in operations management. J Oper Manag. 1998;16(4):361–85.

Karnon J, Mackay M, Mills T, editors. Mathematical modelling in health care. In: 18th World IMACS/MODSIM Congress; 2009: Citeseer.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53.

Carpiano RM, Daley DM. A guide and glossary on post-positivist theory building for population health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(7):564–70.

Creswell J, Creswell J. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. USA: Sage publications; 2017.

Hughes S, Davis TE, Imenda SN. Demystifying theoretical and conceptual frameworks: a guide for students and advisors of educational research. J Soc Sci. 2019;58(1–3):24–35.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychol. 2001;3(3):265–99.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel A guide to designing interventions. 1st ed. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–9.

Mendes AM, Tonin FS, Buzzi MF, et al. Mapping pharmacy journals: a lexicographic analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(12):1464–71.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Prod ESRC Methods Programme Version. 2006;1(1): b92.

Qudah B, Thakur T, Chewning B. Factors influencing patient participation in medication counseling at the community pharmacy: a systematic review. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(11):1863–76.

Alenezi A, Yahyouche A, Paudyal V. Roles, barriers and behavioral determinants related to community pharmacists’ involvement in optimizing opioid therapy for chronic pain: a qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44(1):180–91.

Lindner N, Riesenhuber M, Müller-Uri T, et al. The role of community pharmacists in immunisation: a national cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44(2):409–17.

Isenor JE, Minard LV, Stewart SA, et al. Identification of the relationship between barriers and facilitators of pharmacist prescribing and self-reported prescribing activity using the theoretical domains framework. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14(8):784–91.

Gemmeke M, Koster ES, Rodijk EA, et al. Community pharmacists’ perceptions on providing fall prevention services: a mixed-methods study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(6):1533–45.

Patton DE, Ryan C, Hughes CM. Enhancing community pharmacists’ provision of medication adherence support to older adults: a mixed methods study using the theoretical domains framework. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(2):406–18.

Cardwell K, Hughes CM, Ryan C. Community pharmacists’ views of using a screening tool to structure medicines use reviews for older people: findings from qualitative interviews. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(5):1086–95.

Bertilsson E, Serhal S, Emmerton L, et al. Pharmacists experience of and perspectives about recruiting patients into a community pharmacy asthma service trial. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(3):595–605.

Alatawi YM, Kavookjian J, Ekong G, et al. The association between health beliefs and medication adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12(6):914–25.

Faisal S, Ivo J, Tennant R, et al. Implementation of a real-time medication intake monitoring technology intervention in community pharmacy settings: a mixed-method pilot study. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(2).

Luke MJ, Krupetsky N, Liu H, et al. Pharmacists as personalized medicine experts (PRIME): experiences implementing pharmacist-led pharmacogenomic testing in primary care practices. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(4).

Bright D, Worley M, Porter BL. Patient perceptions of pharmacogenomic testing in the community pharmacy setting. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(4):744–9.

Nichols MA, Arnett SJ, Fa B, et al. National survey identifying community pharmacist preceptors’ experience, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors influencing intent to recommend cannabidiol products. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(4s):S91-s104.

Adeoye OA, Lake LM, Lourens SG, et al. What predicts medication therapy management completion rates? The role of community pharmacy staff characteristics and beliefs about medication therapy management. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2018;58(4s):S7–15.

Paudyal V, Gibson Smith K, MacLure K, et al. Perceived roles and barriers in caring for the people who are homeless: a survey of UK community pharmacists. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(1):215–27.

Jonkman LJ, Tsuchihashi K, Liu E, et al. Patient experiences in managing non-communicable diseases in Namibia. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(11):1550–7.

Okuyan B, Bektay MY, Demirci MY, et al. Factors associated with Turkish pharmacists’ intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine: an observational study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44(1):247–55.

Kennelty KA, Chewning B, Wise M, et al. Barriers and facilitators of medication reconciliation processes for recently discharged patients from community pharmacists’ perspectives. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11(4):517–30.

Amin ME, Chewning B. Predicting pharmacists’ adjustment of medication regimens in Ramadan using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11(1):e1–15.

Tan CL, Gan VB, Saleem F, et al. Building intentions with the Theory of Planned Behaviour: the mediating role of knowledge and expectations in implementing new pharmaceutical services in Malaysia. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2016;14(4):850.

Fleming ML, Bapat SS, Varisco TJ. Using the theory of planned behavior to investigate community pharmacists’ beliefs regarding engaging patients about prescription drug misuse. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(8):992–9.

Gülpınar G, Keleş Ş, Yalım NY. Perspectives of community pharmacists on conscientious objection to provide pharmacy services: a theory informed qualitative study. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(4):373-81.e1.

Falope O, Vamos C, Izurieta R, et al. The knowledge and perceptions of Florida pharmacists in administering inactivated influenza vaccines to pregnant women. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(2).

Hasan SA, Muzumdar JM, Nayak R, et al. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand factors influencing south Asian consumers' intention to seek pharmacist-provided medication therapy management services. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019;7(3).

Rushworth GF, Cunningham S, Pfleger S, et al. A cross-sectional survey of the access of older people in the Scottish Highlands to general medical practices, community pharmacies and prescription medicines. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14(1):76–85.

Hattingh L, Sim TF, Sunderland B, et al. Successful implementation and provision of enhanced and extended pharmacy services. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16(4):464–74.

Murad MS, Spiers JA, Guirguis LM. Expressing and negotiating face in community pharmacist-patient interactions. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13(6):1110–26.

Wash A, Moczygemba LR, Anderson L, et al. Pharmacists’ intention to prescribe under new legislation. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2022;18(5):2837–47.

Seubert LJ, Kerry W, Laetitia H, et al. A theory based intervention to enhance information exchange during over-the-counter consultations in community pharmacy: a feasibility study. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019;7(2).

Seubert LJ, Whitelaw K, Hattingh L, et al. Development of a theory-based intervention to enhance information exchange during over-the-counter consultations in community pharmacy. Pharmacy (Basel). 2018;6(4).

Salgado TM, Moles R, Benrimoj SI, et al. Exploring the role of renal pharmacists in outpatient dialysis centres: a qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(4):569–78.

Amin MEK, Amine A, Newegy MS. Perspectives of pharmacy staff on dispensing subtherapeutic doses of antibiotics: a theory informed qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(5):1110–8.

Humphries B, Collins S, Guillaumie L, et al. Women's beliefs on early adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer: a theory-based qualitative study to guide the development of community pharmacist interventions. Pharmacy (Basel). 2018;6(2).

George DL, Smith MJ, Draugalis JR, et al. Community pharmacists’ beliefs regarding improvement of star ratings scores using the theory of planned behavior. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2018;58(1):21–9.

Ziaei Z, Hassell K, Schafheutle EI. Internationally trained pharmacists’ perception of their communication proficiency and their views on the impact on patient safety. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2015;11(3):428–41.

Chevalier BAM, Watson BM, Barras MA, et al. Hospital pharmacists’ and patients’ views about what constitutes effective communication between pharmacists and patients. Int J Pharm Pract. 2018;26(5):450–7.

Amin ME, Chewning B. Pharmacists’ counseling on oral contraceptives: a theory informed analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12(5):669–81.

Lee SJ, Pincus KJ, Williams AA. Behavioral influences on prescription inhaler acquisition for persistent asthma in a patient-centered medical home. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12(5):789–93.

Desai K, Chewning B, Mott D. Health care use amongst online buyers of medications and vitamins. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2015;11(6):844–58.

Hussein R, Whaley CRJ, Lin ECJ, et al. Identifying barriers, facilitators and behaviour change techniques to the adoption of the full scope of pharmacy practice among pharmacy professionals: using the theoretical domains framework. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(8):1396–406.

Mohammed E, Khanal S, Jalal Z, et al. Perceived barriers and facilitators to uptake of non-traditional roles by pharmacists in Saudi Arabia and implications for COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a qualitative study using Theoretical Domain Framework. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):25.

Puspitasari HP, Costa DSJ, Aslani P, et al. An explanatory model of community pharmacists’ support in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12(1):104–18.

Pinto SL, Lively BT, Siganga W, et al. Using the Health Belief Model to test factors affecting patient retention in diabetes-related pharmaceutical care services. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2006;2(1):38–58.

Waddell J, Nissen L, Hale A. Advanced pharmacy practice in Australia and leadership: mapping the APPF against an evidence-based leadership framework. J Pharm Pract Res. 2017;47.

Demik DE, Vander Weg MW, Lundt ES, et al. Using theory to predict implementation of a physician-pharmacist collaborative intervention within a practice-based research network. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9(6):719–30.

Odukoya OK, Stone JA, Chui MA. How do community pharmacies recover from e-prescription errors? Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2014;10(6):837–52.

Fingleton N, Duncan E, Watson M, et al. Specialist clinicians' management of dependence on non-prescription medicines and barriers to treatment provision: an exploratory mixed methods study using behavioural theory. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019;7(1).

Luder H, Frede S, Kirby J, et al. Health beliefs describing patients enrolling in community pharmacy disease management programs. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(4):374–81.

Viegas R, Godinho CA, Romano S. Physical activity promotion in community pharmacies: pharmacists’ attitudes and behaviours. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2021;19(3):2413.

Abdu-Aguye SN, Mohammed S, Danjuma NM, et al. Improving outpatient medication counselling in hospital pharmacy settings: a behavioral analysis using the theoretical domains framework and behavior change wheel. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2021;19(2):2271.

Luo M, Allman-Farinelli M. Trends in the number of behavioural theory-based healthy eating interventions inclusive of dietitians/nutritionists in 2000–2020. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):4161.

Greene C, Wilson J. The use of behaviour change theory for infection prevention and control practices in healthcare settings: a scoping review. J Infect Prev. 2022;23(3):108–17.

Weston D, Ip A, Amlôt R. Examining the application of behaviour change theories in the context of infectious disease outbreaks and emergency response: a review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1483.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Nili M, Mohamed R, Kelly KM. A systematic review of interventions using health behavioral theories to improve medication adherence among patients with hypertension. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(5):1177–86.

Imeri H, Toth J, Arnold A, et al. Use of the transtheoretical model in medication adherence: a systematic review. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2022;18(5):2778–85.

Power BT, Kiezebrink K, Allan JL, et al. Effects of workplace-based dietary and/or physical activity interventions for weight management targeting healthcare professionals: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Obes. 2014;1:23.

Green J. The role of theory in evidence-based health promotion practice. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(2):125–9.

Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, et al. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(Suppl_1):i3–i9.

Corley KG, Gioia DA. Building theory about theory building: what constitutes a theoretical contribution? Acad Manag Rev. 2011;36(1):12–32.

Stewart D, Klein S. The use of theory in research. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):615–9.

Long KM, McDermott F, Meadows GN. Being pragmatic about healthcare complexity: our experiences applying complexity theory and pragmatism to health services research. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):94.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348: g1687.

Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):1–8.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. No funding from any governmental or non-governmental agency was obtained for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Derek Stewart is the Editor-in-Chief of the International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. He had no role in handling the manuscript, specifically the processes of editorial review, peer review and decision making. Vibhu Paudyal is an Associate Editor of the International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. He had no role in handling the manuscript, specifically the processes of editorial review, peer review and decision making.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nazar, Z., Naseralallah, L.M., Stewart, D. et al. Application of behavioural theories, models, and frameworks in pharmacy practice research based on published evidence: a scoping review. Int J Clin Pharm 46, 559–573 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01674-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01674-x