Abstract

Background

People living with diabetes often experience multiple morbidity and polypharmacy, increasing their risk of potentially inappropriate prescribing. Inappropriate prescribing is associated with poorer health outcomes.

Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to explore and map studies conducted on potentially inappropriate prescribing among adults living with diabetes and to identify gaps regarding identification and assessment of potentially inappropriate prescribing in this group.

Method

Studies that reported any type of potentially inappropriate prescribing were included. Studies conducted on people aged < 18 years or with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes or prediabetes were excluded. No restrictions to language, study design, publication status, geographic area, or clinical setting were applied in selecting the studies. Articles were systematically searched from 11 databases.

Results

Of the 190 included studies, the majority (63.7%) were conducted in high-income countries. None of the studies used an explicit tool specifically designed to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing among people with diabetes. The most frequently studied potentially inappropriate prescribing in high-income countries was contraindication while in low- and middle-income countries prescribing omission was the most common. Software and websites were mostly used for identifying drug-drug interactions. The specific events and conditions that were considered as inappropriate were inconsistent across studies.

Conclusion

Contraindications, prescribing omissions and dosing problems were the most commonly studied types of potentially inappropriate prescribing. Prescribers should carefully consider the individual prescribing recommendations of medications. Future studies focusing on the development of explicit tools to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing for adults living with diabetes are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact statements

-

More studies that assess potentially inappropriate prescribing in low- and middle-income countries, nursing homes and community dwelling settings are needed.

-

Explicit tools specifically designed to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing for adults living with diabetes are lacking.

Introduction

Inappropriate prescribing is a potential threat to patient safety [1]. It may be manifested in the form of overprescribing, misprescribing or underprescribing [2, 3]. Overprescribing is the prescription of a medication that has no clear indication or prescribing two or more agents for the same purpose while a single agent is sufficient. Misprescribing includes prescribing medications at the wrong dose, duration, or frequency, not choosing the first line option or prescribing medications with significant interactions. Underprescribing involves the omission of a beneficial medication [4].

Inappropriate prescribing may result in adverse drug reactions, hospitalization, worsening of the disease and death.[4] People with two or more potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP) indicators have been reported to have twice the risk of emergency visits and adverse events [5]. Nearly one-third of adverse drug reactions in a Swedish older population were attributed to PIP [6]. In addition to increased risk of morbidity and mortality, PIP can also increase health care utilization. A study conducted in Northern Ireland in 2010 estimated that the annual gross cost of PIP was more than €6 million [7].

The two most common factors that contribute to PIP are polypharmacy (5 or more medications) and multiple morbidity (MM) [8, 9]. One of the high-risk patient groups for polypharmacy and MM are people with diabetes mellitus (DM). The prevalence of DM is increasing globally [10]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reported that 463 million people had diabetes in the year 2019 and this is expected to increase to 700 million by 2045 [11]. Diabetes costs the world more than a trillion dollars currently and is estimated to cost US$2.1 trillion by the year 2030 [12]. Globally, about 5 million deaths per year are due to DM [13]. Most people with DM have MM or complications that can include hypertension, dyslipidaemia, nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, cardiovascular, cerebrovascular or peripheral vascular diseases and as a result receive multiple medications. Correspondingly, PIP among people with DM has been reported to be high in a range of international studies [14,15,16,17,18].

Studies have focused on one or more types of PIP (unnecessary drug therapy, omission, contraindication, inappropriate drug selection (IDS), dosing problems, and drug-drug interactions (DDI)) often utilizing different tools for the same type of PIPs. However, no published review article mapping studies on all types of PIP among people with DM was found in our preliminary search on the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PubMed, JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, PROSPERO, Scopus, Informit, ProQuest, EBSCO and Google scholar databases.

Aim

This scoping review aims to explore and map the available evidence and to identify gaps regarding identification and assessment of PIP for adults living with DM.

Method

This scoping review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for scoping reviews[19] and the published protocol [20].

Study selection

Participants

Studies conducted on adults with DM were included in this review. Studies conducted on people aged < 18 years or adults with a diagnosis of gestational DM or prediabetes were excluded.

Concept

PIP is the concept of interest for this scoping review. Studies that reported any type of PIP including contraindications, omissions, dosing problems, DDI, IDS or unnecessary medications were included.

Context

Studies conducted in any health care facility (e.g. hospitals, nursing homes) or clinical setting (e.g. inpatient, outpatient) with no restriction to region, country or geographic area were considered for this review.

Types of sources

Studies with any type of research design were considered for this review. Various types of existing published and unpublished literature including primary research articles, reviews, case reports, theses and dissertations were included. No language restrictions were applied.

Search strategy

The strategy for literature searching was developed with the assistance of a librarian at the University of New England. A three-step search strategy, as suggested by JBI Reviewer’s Manual, was utilized [19]. The first step was an initial limited search on two databases (PubMed and ProQuest). The words in the title and abstracts of the identified studies from these two databases were analysed to create search terms for the subsequent step. In addition, MeSH terms, keywords and thesauruses were searched for the key concepts of inappropriate prescribing and diabetes. The second step applied the full search to multiple databases using the index terms and key words identified in the first step. The following databases were searched from their inception to December 2020: PubMed, EBSCO, Web of Science, ProQuest, Scopus, Cochrane, EMBASE, and Informit. In addition, some grey literature sources including Open Dissertation.org, Open Access Theses and Dissertation, and BIELEFELD Academic Search Engine (BASE) were searched for any unpublished work. In a third step, manual searches of reference lists of included studies were searched for additional articles. The final search results were exported to EndNote X8.2 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and duplicates were removed. A sample search result on PubMed database is shown in the electronic supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1).

Extraction of results

Data extraction was performed using Colandr (Science for Nature and People Partnership, Conservation International, and DataKind, CA, USA), an online application for conducting systematic synthesis of evidence. Data extracted from the studies included author, year, country, publication type (e.g. original article), study design, study population, setting, sample size, types of PIP investigated, prevalence of PIP, medications involved, examples of PIP events, and criteria used in the identification of PIP. Pretesting of the data extraction form was done on a random sample of 10 articles and modified to ensure that all the required information was captured. One study team member (MB) extracted the data and this was manually checked and verified by others (GD, JS).

Data synthesis

Data was exported to Excel then to IBM SPSS version 25 for descriptive statistical analysis. Some of the variables (e.g. year of publication, study country) were categorized into groups. Countries were categorized as high-income and low- and middle-income based on 2020–2021 World Bank classification [21]. The mapping of the included studies was undertaken in terms of the type of PIPs studied against study area, setting, year of publication, and criteria used to assess PIP. All DM related PIPs reported from each study were listed and presented in tables. Prevalence of PIP was summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR).

Results

Study selection

As shown in the PRISMA extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram (Fig. 1), the systematic search resulted in 21,172 published articles and 490 items of grey literature. After removing duplicates, screening the titles, abstracts and full text and adding articles from the reference lists of included studies a total of 190 articles were found eligible for this scoping review.

Study characteristics

Of the 190 included studies, 75.8% were published in the last 10 years. The majority (63.7%) of studies were conducted in high-income countries. Methodologically, 74.7% had a cross-sectional nature (Table 1). Detailed characteristics of included studies are provided in the electronic supplementary material (see Supplementary Table 2).

Criteria for assessment of PIP

Appropriateness of medication therapy was assessed by using a variety of standard references and criteria across the studies. These criteria are summarized in Table 2.

Types of PIP studied

PIPs reported in the included studies were grouped into 6 major classes. Nearly half (47.9%) of the studies reported contraindications. Prescribing omissions were reported by 41.1% of the studies. Unnecessary drug therapy was the least frequently reported PIP (Table 2).

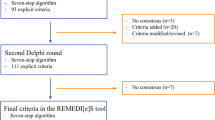

The most frequently studied type of PIP in high-income countries (HICs) was contraindication, while in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) prescribing omissions were more common. Prescribing omissions were more frequently studied in the outpatient setting, whereas contraindication dominated in inpatients and community dwelling patients. The use of software and websites as reference/criteria was more frequently reported in studies that identified DDIs, while clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and explicitly listed criteria were common in studies that identified prescribing omissions and contraindications, respectively (Fig. 2).

Distribution of studies on different types of potentially inappropriate prescribing by country, setting, year of publication and criteria for assessing potentially inappropriate prescribing. Abbreviations:?CPG = clinical practice guideline; DDI = drug-drug interaction; HICs = high-income countries; IDS = inappropriate drug selection; LMICs = low- and middle-income countries; NR = not reported; SMPC = summary of medicinal product characteristics; UDT = unnecessary drug therapy

Specific PIP events and medications involved

The most common PIP events were contraindications – prescribing metformin in the presence of contraindications (e.g. renal failure) and prescribing medications listed in the Beers Criteria or STOPP list for older adults. Not prescribing antiplatelet and lipid lowering agents for eligible individuals were the most commonly reported prescribing omissions. Prescribing incorrect insulin or metformin doses, not adapting the dose of a medication for renal insufficiency and not keeping to the maximum daily dose recommendations were some of the dosing problems reported in the reviewed studies. Examples of specific events in each class of PIP are shown in Table 3. All PIP events reported in the included studies and medications involved are summarized in the electronic supplementary material (see Supplementary Table 3).

Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing

Prevalence of PIP was reported from the included studies in two different ways. Some of the studies reported prevalence for the number of adults with DM in the sample and others took the total number of drug related problems (DRPs). The reported prevalence for each type of PIP varies greatly across the studies (Table 4).

Identified gaps regarding PIP for adults with DM

The following gaps were identified in the study of PIP for adults with DM.

-

PIP is less studied in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where the risk of PIP could be high due to less efficient systems and resource scarcities.

-

PIP is less studied in nursing home and community dwelling adults living with DM.

-

The specific events and conditions that were considered as inappropriate prescribing were inconsistent across included studies.

-

There are no explicit tools/criteria solely designed to identify PIP among adults with DM.

Discussion

The current scoping review included 190 studies reporting on PIP in adults living with DM worldwide. To the authors’ knowledge, this review is the first to comprehensively map, identify and assess PIP in this group. The extent and degree of identification of PIP varied with the type of tool/criteria used. Even though explicit criteria are less costly to use than implicit criteria, require less clinical judgement, and can ensure a higher degree of objectivity, only a quarter of the included studies used explicit criteria. Moreover, almost all the explicit tools used were not specifically designed to detect PIP among people with DM. The majority of explicit tools were designed to identify omissions and contraindications in older populations (e.g. Beers criteria, STOPP and START criteria).

Management of hyperglycaemia

Metformin is the preferred first line pharmacologic agent for people with T2DM, unless contraindicated, because metformin is safe, effective, inexpensive and has beneficial effects on HbA1c, weight loss, and cardiovascular mortality [22, 23]. Many of the reviewed studies considered omission of metformin for adults diagnosed with T2DM as PIP [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

Sulphonylureas should be used with caution because of their risk of serious hypoglycaemia [35]. If the use of sulphonylureas in older individuals is the only option, short acting sulphonylureas (e.g. glipizide) are preferred. Glyburide, a longer acting sulphonylurea, should not be used in older adults because of the increased risk of hypoglycaemia in this patient group [36]. In line with this, many studies that investigated inappropriate prescribing reported that glyburide or chlorpropamide use in an older adult with DM was contraindicated [24, 26, 27, 30,31,32, 34, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) used in the presence of contraindication was reported in nine studies, of which six stated that it was given to adults with heart failure. According to Medscape (WebMD, NY, USA), heart failure is a ‘black box warning’ for thiazolidinediones because they can cause or exacerbate congestive heart failure in some patients. That is why these medications are not recommended for a patient with symptomatic heart failure and their initiation in a patient with established NYHA class III or IV heart failure is contraindicated.[44].

Metabolism and clearance of many of the hypoglycaemic agents is via the kidneys [45]. As a result, prescribing of antidiabetic medications for people with renal impairment is challenging. One of the hypoglycaemic agents that needs special emphasis in the presence of renal impairment is metformin. It is excreted unchanged through the kidneys and accumulates if renal function is impaired. Previously, metformin was contraindicated in males with serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL and females with serum creatinine > 1.4 mg/dL. In 2016 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indicated that metformin should be avoided if estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is < 30 mL/min/1.73m2 [46]. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Australian Diabetes guidelines recommend stopping metformin if GFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m2 [47,48,49]. Mixed results were reported from the included studies regarding the GFR limit used to consider metformin use as inappropriate in an adult with decreased renal function. Huang et al. considered GFR < 60 [50], Lamine et al. and Diab took < 45 [51], (Diab MI, unpublished), and other studies considered a GFR of < 30 mL/min/1.73m2 [52, 53] as the contraindicated level of kidney function for metformin. This difference arose because authors used different criteria as a reference to decide on metformin contraindications.

Beta-blocker use in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycaemic episodes is not recommended because of the high risk of β-blockers causing hypoglycaemia, masking hypoglycaemic symptoms and decreasing hypoglycaemic awareness [54]. Six of the reviewed studies reported that the use of β-blockers in those with diabetes mellitus and frequent hypoglycaemic episodes is PIP [25, 26, 28, 31, 34, 43].

Management of hypertension for adults with DM

Treatment of hypertension to a blood pressure target of < 140/90 mmHg reduces microvascular and cardiovascular events in people with DM [55]. Some of the included studies [14, 56], (Soorapan S, unpublished) reported that adults with diabetes and hypertension were not prescribed antihypertensive therapy. The American Diabetes Association (ADA), 2019 guideline recommends that diabetic patients with confirmed office-based BP ≥ 140/90 should be initiated with antihypertensive treatment. Moreover, ADA recommends starting two antihypertensive agents for people with stage II (≥ 160/100) hypertension to control BP more effectively. In line with this, Ayele et al. reported that monotherapy for people with a stage II hypertension was inappropriate [14]. Initiating two antihypertensive agents for adults with stage I hypertension is also unnecessary because a single agent is usually sufficient to control blood pressure [14]. Similarly, the ADA 2019 guideline recommends starting a single agent for people with an initial blood pressure record of < 160/100 mmHg [22].

The omission of ACEIs/ARBs in adults with diabetes and nephropathy or albuminuria was considered PIP in many of the included studies [24,25,26, 30,31,32,33,34, 57, 58], (Diab MI, unpublished; Aketchi IE, unpublished). Diabetic nephropathy occurs in 20–25% of people with T2DM and is the leading cause of end stage renal disease (ESRD) [59]. ACEIs and ARBs are the preferred agents for treatment of high blood pressure in people with diabetes and urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥ 30 or eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, as these protect against kidney disease progression [49].

Prevention and management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)

People with diabetes have a higher risk of ASCVD as compared to non-diabetic individuals [60]. Lipid lowering therapy is recommended in people with diabetes and a prior CVD or high risk for CVD [22, 23]. A meta-analysis supports the use of a high- or moderate intensity statin as a first line therapy for LDL cholesterol lowering and cardio-protection [61]. Statins have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of CV events and death in people with DM when given as primary or secondary prevention [61, 62]. Consequently, not prescribing a statin therapy to an eligible adult with DM was considered as inappropriate in 28 included studies [2, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, 58, 63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74], (Diab MI, unpublished; Aketchi IE, unpublished; Langenhoven W, unpublished).

People with DM and an established ASCVD should be given an antiplatelet agent as a secondary prevention strategy unless there is a clear contraindication. Most of the diabetes guidelines recommend low dose aspirin (75–350 mg) for this group of people [22, 23, 49]. Omission of antiplatelet therapy (e.g. aspirin) for adults with diabetes and CVD is reported by some of the studies in this review [29, 73, 75,76,77,78,79], (Soorapan S, unpublished; Aketchi IE, unpublished). Use of aspirin as a primary prevention may lead to more benefit than harm in people with high risk of CVD. The ADA guideline recommends the use of aspirin as a primary prevention for people with diabetes and age ≥ 50 with at least one additional major risk factor (family history of premature ASCVD, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking, or chronic kidney disease/albuminuria). Similarly, many of the reviewed studies considered omission of antiplatelet therapy (e.g. aspirin) in adults with DM who are at risk of cardiovascular disease as PIP [24,25,26,27, 29,30,31,32,33,34, 56,57,58, 63, 75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85], (Soorapan S, unpublished; Langenhoven W, unpublished).

Inappropriate prescribing, especially in adults with diabetes, can result in increased morbidity and mortality and increased burden on the healthcare system and costs. Therefore, strategies to prevent and resolve PIP should be sought. Using an explicit tool to identify PIP which can be used as a physicians’ desk reference is a less costly and easy to use strategy to prevent PIP. Tools exist to assess PIP in older people and new tools and criteria frequently emerge. However, they do not specifically target people with diabetes. Only a few items relating to diabetes are usually included in these criteria. We strongly recommend the development of an up-to-date explicit tool that can be used to specifically address PIP for adults with diabetes.

This review included a large number of studies conducted on PIP among people with DM without restrictions to the study area, year and language of publication. Not conducting a critical appraisal of included studies is a limitation of this review and may have resulted in the inclusion of low-quality studies.

Conclusion

PIP is common among people with DM. Contraindications, prescribing omissions and dosing problems were the most commonly reported PIPs. The specific events and conditions that were considered as inappropriate were inconsistent across included studies. PIP was less studied in low- and middle-income countries. There are no explicit criteria specifically designed to measure PIP for adults living with DM. Future studies focusing on the development of explicit tools to identify PIP for adults with DM are needed.

References

Taylor LK, Kawasumi Y, Bartlett G, et al. Inappropriate prescribing practices: the challenge and opportunity for patient safety. Healthc Q (Toronto Ont). 2005;8:81–5.

Formiga F, Vidal X, Agusti A, et al. Inappropriate prescribing in elderly people with diabetes admitted to hospital. Diabet Med. 2016;33:655–62.

Aronson JK. Medication errors: what they are, how they happen, and how to avoid them? QJM. 2009;102:513–21.

O’Connor MN, Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. Inappropriate prescribing: criteria, detection and prevention. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:437–52.

Cahir C, Bennett K, Teljeur C, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse health outcomes in community dwelling older patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:201–10.

Hedna K, Hakkarainen KM, Gyllensten H, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse drug reactions in the elderly: A population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:1525–33.

Bradley MC, Fahey T, Cahir C, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and cost outcomes for older people: A cross-sectional study using the Northern Ireland Enhanced Prescribing Database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1425–33.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2012;380:37–43.

Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, et al. The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions: Population database analysis 1995–2010. BMC Med. 2015;13:74.

Martirosyan L, Braspenning J, Denig P, et al. Prescribing quality indicators of type 2 diabetes mellitus ambulatory care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:318–23.

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 9th edn. 2019 February 12/2020. https://www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed 18.06.2021.

Bommer C, Sagalova V, Heesemann E, et al. Global economic burden of diabetes in adults: projections from 2015 to 2030. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:963–70.

Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–81.

Ayele Y, Melaku K, Dechasa M, et al. Assessment of drug related problems among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with hypertension in Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:728.

Huri HZ, Ling LC. Drug-related problems in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with dyslipidemia. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1192. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1192.

Zaman Huri H, Fun Wee H. Drug related problems in type 2 diabetes patients with hypertension: a cross-sectional retrospective study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;13:2. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6823-13-2.

Inamdar S, Kulkarni R. Drug related problems in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetol. 2016;7:1–12.

Ananchaisarp T, Duangkamsee N, Burapakiat B, et al. Prevalence of under-prescription in elderly type 2 diabetic patients in the primary care unit of a university hospital. J Health Sci Med Res. 2018;36:259–67.

Peters, Michah DJ, Godfrey C, et al. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/. Accessed 17.02.2019.

Ayalew MB, Dieberg G, Quirk F, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing for adults with diabetes mellitus: a scoping review protocol. JBI Evid Synthesis. 2020;18:1557–65.

Serajuddin U, Hamadeh N. New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2020–2021. July 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2020-2021. Accessed 05.08.2021.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1–193.

International Diabetes Federation. Recommendations for managing type 2 diabetes in primary care. 2017. http://www.idf.org/managing-type2-diabetes. Accessed 12.09.2019.

Mori AL, Carvalho RC, Aguiar PM, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and associated factors in elderly patients at hospital discharge in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:386–93.

Kara O, Arik G, Kizilarslanoglu MC, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing according to the STOPP/START criteria for older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28:761–8.

Blundell DB. Medication review according to STOPP-START criteria in older patients from the dose administration aids service of a community pharmacy. Farmaceuticos Comunitarios. 2015;7:31–6.

Marroquín EC, Iglesia NM, Cobos LP. Adequacy of medication in patients 65 years or older in teaching health centers in Cáceres, Spain. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2012;86:419–34.

Karandikar Y, Chaudhari S, Dalal N, et al. Inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: A comparison of two validated screening tools. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;4:109–14.

Liu C-L, Peng L-N, Chen Y-T, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing (IP) for elderly medical inpatients in Taiwan: A hospital-based study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:148–51.

Kovačević SV, Simišić M, Rudinski SS, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in older primary care patients. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95536. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0095536.

Frankenthal D, Lerman Y, Lerman Y. The impact of hospitalization on potentially inappropriate prescribing in an acute medical geriatric division. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:60–7.

López NP, Villán YFV, Menéndez MIG, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in patients over 65 years-old in a primary care health centre. Aten Primaria. 2014;46:290–7.

Luz AC, de Oliveira MG, Noblat L. Prescribing omissions among elderly Brazilian patients at their hospital admission and discharge: Cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1596–600.

Siripala U, Premadasa S, Samaranayake N, et al. Usefulness of STOPP/START criteria to assess appropriateness of medicines prescribed to older adults in a resource-limited setting. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41:525–30.

Roumie CL, Hung AM, Greevy RA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of sulfonylurea and metformin monotherapy on cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:601–10.

Fick D, Semla T, Beizer J, et al. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–46.

Al Khaja KA, Isa HA, Veeramuthu S, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults with hypertension or diabetes mellitus and hypertension in a primary care setting in Bahrain. Med Princ Pract. 2018;27. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1159/000488055.

Terán-Álvarez L, González-García M, Rivero-Pérez A, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescription according to the “STOP” criteria in heavily polymedicated elderly patients. Semergen. 2016;42:2–10.

Herman H, San IP, Ningsih R, et al. Inappropriate use of the drug to elderly patients with type-II diabetes mellitus in Makassar, Indonesia. Der Pharmacia Lettre. 2016;8:154–8.

Caughey G, Barratt J, Shakib S, et al. Medication use and potentially high risk prescribing in older patients hospitalized for diabetes: A missed opportunity to improve care. Diabet Med. 2017;34:432–9.

Caughey GE, Roughead EE, Vitry AI, et al. Comorbidity in the elderly with diabetes: identification of areas of potential treatment conflicts. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:385–93.

Erah PO, Eroje HI. Prescribing of antidiabetic medicines to older diabetes type 2 patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2013;23:12–6.

Aqqad SMA, Chen LL, Shafie AA, et al. The use of potentially inappropriate medications and changes in quality of life among older nursing home residents. Clin Interv Aging 2014;9. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S52356.

Mudaliar S, Chang AR, Henry RR. Thiazolidinediones, peripheral edema, and type 2 diabetes: incidence, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. Endocr Pract. 2003;9:406–16.

Zanchi A, Lehmann R, Philippe J. Antidiabetic drugs and kidney disease: Recommendations of the Swiss Society for Endocrinology and Diabetology. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2012.13629.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA revises warnings regarding use of the diabetes medicine metformin in certain patients with reduced kidney function. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/media/96771/download. Accessed 18.08.2021.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm–2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:91–121.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. NICE guideline 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28. Accessed 12.12.2019.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. General practice management of type 2 diabetes: 2016–18. RACGP: East Melbourne, Vic; 2016.

Huang DL, Abrass IB, Young BA. Medication safety and chronic kidney disease in older adults prescribed metformin: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:86. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-15-86.

PLamine F, Lalubin F, Pitteloud N, et al. Chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetic patients followed-up by primary care physicians in Switzerland: Prevalence and prescription of antidiabetic drugs. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146:w14282. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2016.14282.

Ruiz-Tamayo I, Franch-Nadal J, Mata-Cases M, et al. Noninsulin antidiabetic drugs for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Are we respecting their contraindications? J Diabetes Res. 2016;7502489. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7502489.

Taner N, Çattık BN, Berk B. A contraindication to metformin therapy: Renal impairment-Adherence to prescribing guidelines at a hospital in Turkey. Acta Pharm Sci. 2018;56:63–70.

Hackethal V. Beta-blockers in type 2 Diabetes: Time to Reconsider? 2018. https://www.endocrinologynetwork.com/cardiovascular-health/beta-blockers-type-2-diabetes-time-reconsider. Accessed 06.10.2019.

Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood-pressure-lowering treatment on outcome incidence in hypertension: Should blood pressure management differ in hypertensive patients with and without diabetes mellitus? Overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2017;35:922–44.

Vaccaro O, Boemi M, Cavalot F, et al. The clinical reality of guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes in Italy. Atherosclerosis. 2008;198:396–402.

LaMarr B, Valdez C, Driscoll K, et al. Influence of pharmacist intervention on prescribing of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II-receptor blockers, and aspirin for diabetic patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:290–4.

Yeste-Gomez I, Duran-Garcia ME, Muino-Miguez A, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescriptions in the ambulatory treatment of elderly patients. Rev Calid Asist. 2014;29:22–8.

Thomas MC, Weekes AJ, Broadley OJ, et al. The burden of chronic kidney disease in Australian patients with type 2 diabetes (the NEFRON study). Med J Aust. 2006;185:140–4.

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–245.

Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–81.

Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:117–25.

Galvan-Banqueri M, Gonzalez-Mendez AI, Alfaro-Lara ER, et al. Evaluation of the appropriateness of pharmacotherapy in patients with high comorbidity. Aten Primaria. 2013;45:235–43.

Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: A retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1035–40.

Elnaem M, Nik Mohamed M, Huri H, et al. Patterns of statin therapy prescribing among hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in two Malaysian tertiary hospitals. Trop J Pharm Res. 2017;16:3005–11.

Simons LA, Chung E. Are high coronary risk patients missing out on lipid lowering drugs in Australia? Med J Aust. 2014;201:213–6.

Yimama M, Jarso H, Desse. TA Determinants of drug-related problems among ambulatory type 2 diabetes patients with hypertension comorbidity in South West Ethiopia: A prospective cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:679. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3785-8.

Doellner JF, Dettloff RW, DeVuyst-Miller S, et al. Prescriber acceptance rate of pharmacists’ recommendations. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57:197–202.

Salgueiro E, Elizarde BC, Elola AI, et al. The most common STOPP/START criteria in Spain. A review of the literature. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2018;53:274–8.

Elnaem MH, Mohamed MHN, Huri HZ, et al. Effectiveness and prescription pattern of lipid-lowering therapy and its associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Malaysian primary care settings. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S182716.

Anderson SL, Marrs JC, Chachas CR, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-led intervention to improve statin use in persons with diabetes. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26:910–7.

Elnaem MH, Mohamed MHN, Huri HZ. Pharmacist-led academic detailing improves statin therapy prescribing for Malaysian patients with type 2 diabetes: Quasi-experimental design. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0220458. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220458.

Kochetkov AI, De VA, Voevodina NY, et al. The application of the STOPP/START criteria in the elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and essential hypertension at the endocrinology department of a multidisciplinary hospital. Arterial Hypertens. 2019;25:214–24.

Mwita JC, Godman B, Esterhuizen TM. Statin prescription among patients with type 2 diabetes in Botswana: Findings and implications. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20:1–9.

Harder S, Saal K, Blauth E, et al. Appropriateness and surveillance of medication in a cohort of diabetic patients on polypharmacy. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;47:104–10.

Bulatova NR, Al Motassem FY, AbuRuz SM. Antiplatelet therapy for primary and secondary prevention in Jordanian patients with diabetes mellitus. Thromb Res. 2007;121:43–50.

Woodward A, Bayley D, Overend L, et al. Antiplatelet drug use in a diabetic clinic. QJM. 2007;100:547–50.

Pasina L, Novella A, Elli C, et al. Inappropriate use of antiplatelet agents for primary prevention in nursing homes: An Italian multicenter observational study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20:828–32.

Haggerty SA, Cerulli J, Zeolla MM, et al. Community pharmacy target intervention program to improve aspirin use in persons with diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005;45:17–22.

van Roozendaal BW, Krass I. Development of an evidence-based checklist for the detection of drug related problems in type 2 diabetes. Pharm World Sci. 2009;31:580–95.

Leitão CB, Krahe AL, Nabinger GB, et al. Aspirin therapy is still underutilized among patients with type 2 diabetes. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2006;50:1014–9.

Faragon JJ, Waite NM, Hobson EH, et al. Improving aspirin prophylaxis in a primary care diabetic population. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:73–9.

Klinke JA, Johnson JA, Guirguis LM, et al. Underuse of aspirin in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Prevalence and correlates of therapy in rural Canada. Clin Ther. 2004;26:439–46.

Kassam R, Meneilly GS. Role of the pharmacist on a multidisciplinary diabetes team. Can J Diabetes. 2007;31:215–22.

Kolawole B, Adebayo R, Aloba O. An assessment of aspirin use in a Nigerian diabetes outpatient clinic. Niger J Med. 2004;13:405–6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the research librarians at the University of New England for their assistance in developing the strategy for literature searching and assisting with interlibrary loans. Mohammed Biset Ayalew is the recipient of a University of New England International Postgraduate Research Award (UNE IPRA) scholarship to support his PhD research.

Funding

No specific funding was received.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayalew, M.B., Spark, M.J., Quirk, F. et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing for adults living with diabetes mellitus: a scoping review. Int J Clin Pharm 44, 860–872 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-022-01414-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-022-01414-7