Abstract

Purpose

Human tuberculosis (TB) is a global health problem that causes nearly 2 million deaths per year. Anti-TB therapy exists, but it needs to be administered as a cocktail of antibiotics for six months. This lengthy therapy results in low patient compliance and is the main reason attributable to the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Methods

One alternative approach is to combine anti-TB multidrug therapy with inhalational TB therapy. The aim of this work was to develop and characterize dry powder formulations of spectinamide 1599 and ensure in vitro and in vivo delivered dose reproducibility using custom dosators.

Results

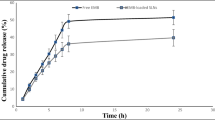

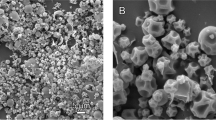

Amorphous dry powders of spectinamide 1599 were successfully spray dried with mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) = 2.32 ± 0.05 μm. The addition of L-leucine resulted in minor changes to the MMAD (1.69 ± 0.35 μm) but significantly improved the inhalable portion of spectinamide 1599 while maintaining amorphous qualities. Additionally, we were able to demonstrate reproducibility of dry powder administration in vitro and in vivo in mice.

Conclusions

The corresponding systemic drug exposure data indicates dose-dependent exposure in vivo in mice after dry powder intrapulmonary aerosol delivery in the dose range 15.4 - 32.8 mg/kg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- 1599:

-

Spectinamide 1599

- API:

-

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient

- APSD:

-

Aerodynamic particle size determination

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- Cmax :

-

Peak plasma concentration

- DI:

-

Deionized

- DPI:

-

Dry powder inhaler

- DSC:

-

Differential scanning calorimetry

- EMB:

-

Ethambutol

- FPFED :

-

Emitted dose fine particle fraction

- FPFN :

-

Nominal fine particle fraction

- GSD:

-

Geometric standard deviation

- HILIC:

-

Hydrophobic interatom liquid chromatography

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HPMC:

-

Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose

- INH:

-

Isoniazid

- KF:

-

Karl Fischer titration

- Leu:

-

L-leucine

- MDR:

-

Multiple drug-resistant

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MMAD:

-

Mass median aerodynamic diameter

- Mtb :

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- NGI:

-

Next generation impactor

- PK:

-

Pharmacokinetic

- PZA:

-

Pyrazinamide

- RH:

-

Relative Humidity

- RIF:

-

Rifampicin

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- TGA:

-

Thermogravimetric analysis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- XDR:

-

Extensively drug-resistant

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

References

WorldHealthOrganization. Tuberculosis Key Facts. WHO Press. Available from: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. March 2019

Sloan DJ, Davies GR, Khoo SH. Recent advances in tuberculosis: New drugs and treatment regimens. Curr Respir Med Rev 2013;9(3):200–10.

Murray S, Mendel C, Spigelman MTB. Alliance regimen development for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016;20(12):S38–41.

Misra A, Hickey AJ, Rossi C, Borchard G, Terada H, Makino K, et al. Inhaled drug therapy for treatment of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2011;91(1):71–81.

Hickey AJ, Durham PG, Dharmadhikari A, Nardell EA. Inhaled drug treatment for tuberculosis: Past progress and future prospects. J. Control. Release. 2016;240:127–34.

Mitchison DA, Fourie PB. The near future: improving the activity of rifamycins and pyrazinamide. Tuberculosis (Edinb.). 2010;90(3):177–81.

Muttil P, Wang C, Hickey AJ. Inhaled drug delivery for tuberculosis therapy. Pharm. Res. 2009;26(11):2401–16.

Blasi P, Schoubben A, Giovagnoli S, Rossi C, Ricci M. Fighting tuberculosis: old drugs, new formulations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2009;6(9):977–93.

Parumasivam T, Chang RY, Abdelghany S, Ye TT, Britton WJ, Chan HK. Dry powder inhalable formulations for anti-tubercular therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;102:83–101.

de Boer AH, Hagedoorn P, Hoppentocht M, Buttini F, Grasmeijer F, Frijlink HW. Dry powder inhalation: past, present and future. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2017;14(4):499–512.

Sou T, Meeusen EN, de Veer M, Morton DA, Kaminskas LM, McIntosh MP. New developments in dry powder pulmonary vaccine delivery. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29(4):191–8.

Garcia-Contreras L, Sung JC, Muttil P, Padilla D, Telko M, Verberkmoes JL, et al. Dry powder PA-824 aerosols for treatment of tuberculosis in guinea pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54(4):1436–42.

Suarez S, O’Hara P, Kazantseva M, Newcomer CE, Hopfer R, McMurray DN, et al. Airways delivery of rifampicin microparticles for the treatment of tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;48(3):431–4.

Dharmadhikari AS, Kabadi M, Gerety B, Hickey AJ, Fourie PB, Nardell E. Phase I, single-dose, dose-escalating study of inhaled dry powder capreomycin: a new approach to therapy of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57(6):2613–9.

Lee RE, Hurdle JG, Liu J, Bruhn DF, Matt T, Scherman MS, et al. Spectinamides: a new class of semisynthetic antituberculosis agents that overcome native drug efflux. Nat. Med. 2014;20(2):152–8.

Robertson GT, Scherman MS, Bruhn DF, Liu J, Hastings C, McNeil MR, et al. Spectinamides are effective partner agents for the treatment of tuberculosis in multiple mouse infection models. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72(3):770–7.

Rathi C, Lukka PB, Wagh S, Lee RE, Lenaerts AJ, Braunstein M, et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics of spectinamide 1599 after subcutaneous and intrapulmonary aerosol administration in mice. Tuberculosis. 2019;114:119–22.

Liu J, Bruhn DF, Lee RB, Zheng Z, Janusic T, Scherbakov D, et al. Structure-Activity Relationships of Spectinamide Antituberculosis Agents: A Dissection of Ribosomal Inhibition and Native Efflux Avoidance Contributions. ACS Infect Dis 2017;3(1):72–88.

U.S.P. Convention, U.S. Pharmacopeia National Formulary 2011: USP 34 NF 292011.

Durham PG, Zhang Y, German N, Mortensen N, Dhillon J, Mitchison DA, et al. Spray Dried Aerosol Particles of Pyrazinoic Acid Salts for Tuberculosis Therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2015;12(8):2574–81.

Srichana T, Martin GP, Marriott C. Dry powder inhalers: the influence of device resistance and powder formulation on drug and lactose deposition in vitro. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998;7(1):73–80.

Durham PG, Hanif SN, Contreras LG, Young EF, Braunstein MS, Hickey AJ. Disposable dosators for pulmonary insufflation of therapeutic agents to small animals. JoVE. 2017(121):e55356.

Mager H, Goller G. Resampling methods in sparse sampling situations in preclinical pharmacokinetic studies. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998;87(3):372–8.

Vehring R. Pharmaceutical particle engineering via spray drying. Pharm. Res. 2008;25(5):999–1022.

Vehring R, Foss WR, Lechuga-Ballesteros D. Particle formation in spray drying. J. Aerosol Sci. 2007;38(7):728–46.

Wolfenden R, Andersson L, Cullis PM, Southgate CCB. Affinities of amino acid side chains for solvent water. Biochemistry. 1981;20(4):849–55.

Gliński J, Chavepeyer G, Platten J-K. Surface properties of aqueous solutions of l-leucine. Biophys. Chem. 2000;84(2):99–103.

Seville PC, Learoyd TP, Li HY, Williamson IJ, Birchall JC. Amino acid-modified spray-dried powders with enhanced aerosolisation properties for pulmonary drug delivery. Powder Technol. 2007;178(1):40–50.

Chew NY, Chan HK. Use of solid corrugated particles to enhance powder aerosol performance. Pharm. Res. 2001;18(11):1570–7.

Peng T, Lin S, Niu B, Wang X, Huang Y, Zhang X, et al. Influence of physical properties of carrier on the performance of dry powder inhalers. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6(4):308–18.

Weiler C, Egen M, Trunk M, Langguth P. Force control and powder dispersibility of spray dried particles for inhalation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;99(1):303–16.

Boraey MA, Hoe S, Sharif H, Miller DP, Lechuga-Ballesteros D, Vehring R. Improvement of the dispersibility of spray-dried budesonide powders using leucine in an ethanol–water cosolvent system. Powder Technol. 2013;236:171–8.

Sou T, Kaminskas LM, Nguyen T-H, Carlberg R, McIntosh MP, Morton DAV. The effect of amino acid excipients on morphology and solid-state properties of multi-component spray-dried formulations for pulmonary delivery of biomacromolecules. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013;83(2):234–43.

Simon A, Amaro MI, Cabral LM, Healy AM, de Sousa VP. Development of a novel dry powder inhalation formulation for the delivery of rivastigmine hydrogen tartrate. Int. J. Pharm. 2016;501(1–2):124–38.

Feng AL, Boraey MA, Gwin MA, Finlay PR, Kuehl PJ, Vehring R. Mechanistic models facilitate efficient development of leucine containing microparticles for pulmonary drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;409(1):156–63.

Li L, Sun S, Parumasivam T, Denman JA, Gengenbach T, Tang P, et al. L-Leucine as an excipient against moisture on in vitro aerosolization performances of highly hygroscopic spray-dried powders. European journal of pharmaceutics and biopharmaceutics: official journal of Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Pharmazeutische Verfahrenstechnik eV. 2016;102:132–41.

Mangal S, Meiser F, Tan G, Gengenbach T, Denman J, Rowles MR, et al. Relationship between surface concentration of l-leucine and bulk powder properties in spray dried formulations. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015;94:160–9.

Kaewjan K, Srichana T. Nano spray-dried pyrazinamide-l-leucine dry powders, physical properties and feasibility used as dry powder aerosols. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2016;21(1):68–75.

Chang Y-X, Yang J-J, Pan R-L, Chang Q, Liao Y-H. Anti-hygroscopic effect of leucine on spray-dried herbal extract powders. Powder Technol. 2014;266:388–95.

Telko MJ, Hickey AJ. Dry powder inhaler formulation. Respir. Care. 2005;50(9):1209–27.

Tseng H-C, Lee C-Y, Weng W-L, Shiah IM. Solubilities of amino acids in water at various pH values under 298.15 K. Fluid Phase Equilibria. 2009;285(1):90–5.

Shetty N, Park H, Zemlyanov D, Mangal S, Bhujbal S, Zhou Q. Influence of excipients on physical and aerosolization stability of spray dried high-dose powder formulations for inhalation. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;544(1):222–34.

Eedara BB, Rangnekar B, Doyle C, Cavallaro A, Das SC. The influence of surface active l-leucine and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DPPC) in the improvement of aerosolization of pyrazinamide and moxifloxacin co-spray dried powders. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;542(1–2):72–81.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

The authors would like to acknowledge Jennifer Arab and Amanda Walz from Colorado State University for their technical contributions and Phillip Durham, now at UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy (Chapel Hill, NC, USA), for his insightful discussions. XRD analysis was performed by Todd Ennis at RTI International and XPS analysis was completed by Mark Walters at the Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility (SMIF) at Duke University (Durham, NC, USA). This work was supported by NIH R01 AI120670, R01 AI090810, S10OD016226 and ALSAC, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 1262 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stewart, I.E., Lukka, P.B., Liu, J. et al. Development and Characterization of a Dry Powder Formulation for Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Spectinamide 1599. Pharm Res 36, 136 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-019-2666-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-019-2666-8