Abstract

Clergy play significant leadership, educational, and caregiving roles in society. However, burnout is a concern for the clergy profession, those they serve, and their families. Effects include decreased ministry effectiveness, lower sense of personal accomplishment in their role, and negative impacts on quality of family life and relationships. Given these risks, knowledge of the nature of Christian clergy’s current resilience and well-being in Canada may provide valuable intelligence to mitigate these challenges. In summary, the purpose of this research was to describe and analyze the status of clergy resilience and well-being in Canada, together with offering focused insights. Resilience and well-being surveys used by the co-authors with educators and nurses were adapted for use in this study. This instrument was developed to gain insight into baseline patterns of resilience and well-being and included questions across seven sections: (1) demographic information. (2) health status, (3) professional quality of life, (4) Cantril Well-Being Scale, (5) Ego-Resiliency Scale, (6) Grit Scale, and (7) open-ended questions. The findings provided valuable insights into clergy well-being and resilience that can benefit individual clerics, educational institutions, denominations, and congregations. The participants’ current resilience and well-being included high levels of resiliency, moderate grit, and satisfaction with health and wellness. Other significant findings included the impact of congregational flourishing and age. This study found that clergy well-being and resilience was doing well despite the increased adversity of the COVID-19 pandemic. Implications of this study are that clerics may need unique supports based on their age and also whether they serve in a congregation they perceive as flourishing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The adversity and challenges clergy face, along with burnout risk factors, are significant. Grudem (2016) found that an unreasonable sense of calling and responsibility to change the world was a burnout risk for clergy, as were their expectations of personal and professional perfection. Proeschold-Bell et al. (2015) emphasized the pressure on clergy arising from the sacred nature of clergy calling, which included the spiritual expectations to be skilled in biblical and theological knowledge. Pressure on clergy also includes the expectations that they be engaged in personal spiritual transformation and exemplify personal spirituality (Coate, 1989).

Historically, clergy have held prominence in society due to their relative level of education and symbolic societal roles. However, this status has fallen in modern society as the clergy’s education is no longer above the average person in society and both the church and clergy have been associated with scandals (Means, 1989). In the past, clergy were also expected to take a symbolic role as parent figures for their congregations, and they thus received the congregant’s emotional projections (Avis, 1992). Further, limited resources, multiple roles and responsibilities, high expectations, low appreciation, modest salaries, and social isolation have also put clergy at risk for burnout (Abernethy et al., 2016).

As clergy roles have become increasingly complex in modern society, role complexity is another challenge, and this is associated with a great deal of ambiguity and confusion (Means, 1989). The roles now entail far more than preaching and teaching. Ershova and Hermelink (2012) highlighted two sides of congregational organizations: the spiritual and the administrative. The spiritual and administrative roles require different skills, and clergy are judged on both their technical abilities and appearance of spirituality (Malony & Hunt, 1991). Additional role complexity is found in the expectation of clergy to show prophetic leadership in calling congregants to change and grow spiritually (Oswald & Johnson, 2010). Also, clergy are required to be attuned to the culture and values of the church and local community (Burt, 1988) while sustaining faithfulness to ecclesiastical tradition and values.

While an understanding of risk factors and adversity that clergy face is essential, Malcolm et al. (2019) emphasized that the absence of stress does not equate to wellness. Also, it is necessary to understand the factors that bring satisfaction in vocational ministry life as these are separate dimensions. Core satisfiers are considered “aspects of ministry life often described as life-giving, enjoyable, satisfying, meaningful, or fulfilling” (Malcolm et al., 2019, p. 324). In comparison, core stressors are defined as “aspects that are often experienced as unenjoyable, unsatisfying, uncomfortable, meaningless, stressful, discouraging, life- eroding, or frustrating” (Malcolm et al., 2019, p. 325).

Proeschold-Bell et al. (2015) also considered satisfaction and stressors related to clergy mental health. They identified four categories of clergy satisfaction: (1) work satisfaction, (2) interpersonal relationships, (3) intrapersonal satisfaction, and (4) family satisfaction. Ministry stressors were found to be mainly interpersonal, and increasing social support, decreasing social isolation, and decreasing financial stress were identified as essential to promoting clergy’s positive mental health (Proeschold-Bell et al., 2015). Clergy who experienced congregational support reported greater ministry satisfaction, whereas critical congregants were connected to clergy negative mental health, lower ministry satisfaction, and lower quality of life (Proeschold-Bell et al., 2015). Although previously published studies provide insight into potential adversity and stress among clergy, as well as some aspects of satisfaction, there are no studies that contextualize the current state of well-being and resilience of Canadian Christian clergy.

The early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased workload and stress for clergy (Clarke, 2021). Stress occurred due to the pace of the transition, not being able to return to in-person services, concern for congregants impacted by COVID-19, working from home, and the financial impact of the pandemic on churches. The workload of clergy became even more multifaceted during the pandemic due to the need to provide online services and minister to congregants remotely. In the midst of the altered and increased pandemic workload, clergy lost access to supportive resources such as physical exercise or clergy gatherings (Clarke, 2021).

The early phase of the pandemic also resulted in some unique opportunities (Clarke, 2021). For some clergy, the pandemic was a time of evaluation of priorities, such as contact with family. Increased time with God was an opportunity found by some clergy during the pandemic. New ministry opportunities during the pandemic were also valued by some clergy (Clarke, 2021).

This Canadian study of Christian clergy well-being and resilience

The purpose of this research was to describe and analyze the status of clergy resilience and well-being in Canada, together with offering focused insights. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive pan-Canadian study of clergy well-being and resilience that has been conducted. It is comprehensive because we included Catholic, mainline Protestant, and conservative Protestant clergy from across Canada and because we used multiple instruments for the analyses.

Of course, context matters, and so for readers who are not familiar with the Canadian religious setting, we offer a few elements of this important background. Within the frames of this study of Christian clergy, it is useful to know that in 2019 approximately 68% of the Canadian population (15 years of age and older) identified as having a religious affiliation (72% of women and 64% of men). Sixty-three percent affiliated with a Christian religion. Roman Catholic adherents represented the largest religious group in Canada with 32% of the population; Protestants, Eastern Orthodox, and other Christian groups constituted the remaining 31%. About 10% of Canadians identified as Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jewish, or other spiritual traditions, and about 26.3% of Canadians indicated “no religious affiliation” or a secular perspective (Cornelissen, 2021; Statistics Canada, 2021).

The findings reported in this paper were part of a mixed-methods dissertation study investigating clergy resilience (Clarke, 2021). The study included quantitative data collection through a national survey as well as qualitative data through open-ended survey questions, one-on-one interviews, and an interpretation panel. This article reports on the quantitative data collected through the national survey.

Methods employed for the Canadian Christian clergy resilience and well-being survey

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Board of the University of Saskatchewan. The Clergy Resilience and Well-Being Survey was distributed online (June 5–July 20, 2020) to participants from Catholic, mainline Protestant, and conservative Protestant traditions in Canada. The participant sample was developed through internet searches, key denominational contacts, and resources of Flourishing Congregations Institute, which partnered with this research. The survey included questions across seven sections: (1) demographic information, (2) health status, (3) professional quality of life, (4) Cantril Well-Being scale, (5) Ego-Resiliency scale, (6) Grit-S scale, and (7) open-ended questions.

The survey instrument elements had been used in two previous studies, but adaptations in the demographics and open-ended question sections and in some terminology were made to fit the clergy population. The full adapted survey instrument was piloted with three clergy and two researchers to get feedback on the clarity of terminology and questions. Feedback from the survey pilot was incorporated into the final survey.

As indicated, the survey link was shared with Canadian Christian clergy in collaboration the Flourishing Congregations Institute through the institute’s website, social media, and emails. Collaboration also occurred with four districts of the Christian and Missionary Alliance in Canada, and the Canadian Church of God Ministries in Western Canada shared the survey link with their clerics. After approximately one month of the survey administration, the denominations of participants were reviewed. Several denominations with lower participation rates were targeted by harvesting publicly available contacts in order to further ensure wider denominational participation. The targeted denominations were Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, Evangelical Lutheran, Presbyterian, United Church of Canada, and Orthodox Church of America.

Participants gave informed consent at the beginning of the survey and were invited to not answer any question they did not wish to and/or to withdraw at any point before finishing the survey and submitting it. The survey took approximately 20 min to complete. No incentives were offered for completing the survey.

Measures used to ascertain the resilience and well-being of Canadian Christian clergy

In this section, we briefly delineate the health status scales, Professional Quality of Life scale, the two-item Cantril Ladder scale, the Grit scale, and the Ego-Resiliency scale used in this study.

Health status scales

Three scales were used to rate the participant’s health and well-being: a one-item scale about current health today, a five-item scale about health in general, and an eight-item scale assessing holistic well-being. The first scale about health asked participants to rate their current state of health or unhealth using a scale of zero to 100, with 100 indicating the best state and 0 indicating the worst state.

Following the rating of their current state of health, five items asked participants about their health in general which were adapted from the EQ-5D-5L (EuroQol Research Foundation, 2019) and were rated on a 5-point scale of 1= not like me at all, 2 = not much like me, 3 = somewhat like me, 4 = mostly like me, and 5 = very much like me. The five questions were: (1) I have no problems in walking about (mobility), (2) I have no problems with self-care (self-care), (3) I have no problems with performing my usual activities (usual activities: work, study, housework family, leisure), (4) I have no pain or discomfort (pain, discomfort), and (5) I am not anxious or depressed (anxiety/depression). Possible cumulative scores for this scale ranged from five to 25.

The holistic well-being satisfaction scale asked participants to rate the eight wellness dimensions—occupational, environmental, intellectual, social, spiritual, physical, emotional, and financial. Participants rated their satisfaction in each of these domains based on a 5-point scale of 1= not at all satisfied, 2 = often dissatisfied, 3 = somewhat satisfied, 4 = mostly satisfied, and 5= very much satisfied. Possible cumulative scores for this scale ranged from 8 to 40.

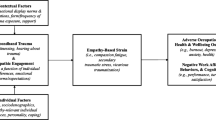

Professional quality of life (ProQOL) scale

An adaptation of the 30-item Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale was used to measure the dimensions of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue (Stamm, 2010). Compassion satisfaction measures the pleasure found in doing work, whereas compassion fatigue measures the burnout factors of exhaustion, anger, and depression and negative feelings and fear associated with secondary trauma (Stamm, 2010). ProQOL is used to measure helping professionals’ feelings towards their work as a helper and has been validated in over 200 published articles (Stamm, 2010).

Compassion fatigue is broken down into two subscales, burnout and secondary trauma. The burnout subscale considers factors of exhaustion, anger, and depression and the secondary trauma scale considers negative feelings and fear associated with secondary trauma (Stamm, 2010). Participants are asked to indicate on a scale of 1 to 5 how much each statement is like them, with 1 = not like me at all and 5 = very much like me. Of the 30 statements, scores from 10 of the statements are used for each of the subscales of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma. The ProQOL scores were converted from “Z scores to t‐scores with raw score mean = 50 and the raw score standard deviation = 10” (Stamm, 2010, p. 16). The ProQOL scoring manual also identified cut scores at the 25th and 75th percentiles to indicate risk or protective factors for each of the subscales.

The Clergy Resilience and Well-Being Survey used an adaptation of the previously validated 30-item Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale which measures the dimensions of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue (Stamm, 2010). The alpha scale reliability of the ProQOL is 0.88 (Stamm, 2010). The scale was adapted for clergy participants by using the following introductory phrase for each statement: “To help us understand the impact of your helping work as clergy, please answer the following questions. In your role as a clergy...” Also, questions that used the word “helper” were changed to “clergy.”

Cantril Ladder

The two-question Cantril Ladder Well-Being Scale, is a self-anchoring ladder, and asks participants to self-report well-being on an 11-point scale (0–10; OECD, 2013). This scale gauges individual aspirations and perceptions (Mazur et al., 2018). The first Cantril question focused on participants’ current sense of life satisfaction, and the second focused on their anticipation of where they would be in five years. The possible scores ranged from 0, which represented the worst possible life, to 10, which represented the best possible life. The Cantril questions provided insight into participants’ overall life satisfaction.

Kilpatrick and Cantril (1960) describe this self-anchoring as a “first-person point of view” (p. 158). Although there are few validation studies of the scale, Mazur et al. (2018) stated that “for 50 years the Cantril Scale (CS) has been cited as being an effective tool for measuring general well-being, mental health and happiness” (p. 182). Burckhardt and Anderson (2003) considered the Cantril Ladder a commonly circulated measure that showed the most attention to individual perspective and diversity.

Grit scale

The Short Grit scale (Grit-S) is an 8-item scale that “measures trait-level perseverance and passion for long-term goals” and is comprised of two distinct facets of sustained stamina and effort (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009, p. 166). Duckworth and Quinn (2009) found that Grit-S significantly predicted fewer lifetime career changes. Resilience is an inherent aspect of grit (Stoffel & Cain, 2018), making grit an interesting aspect to consider. Participants rate eight questions related to aspects such as setback, focus, goals, and diligence on a 5-point scale ranging from very much like me to not like me at all. Half the questions are reverse scored, and total points are divided by eight for a score ranging from 5, which indicates “extremely gritty,” to 1, which means “not gritty at all.”Footnote 1

Ego-resiliency scale

The Ego-Resiliency scale is a 14-item self-report scale for ego-control and ego-resiliency using a 5-point scale (Block & Kremen, 1996). Possible cumulative scores for this scale range from 0 to 56. Score interpretation is as follows: very low resiliency trait (0–10), low resiliency trait (11–22), undetermined trait (23–24), high resiliency trait (35–46), and very high resiliency trait (47–56). There is no specific clinical application recommended for the Ego-Resiliency scale, and Windle et al. (2011) stated that “ego-resiliency may be one of the protective factors implicated in a resilient outcome, but it would be incorrect to use this measure on its own as an indicator of resilience” (p. 8).

Summary of the scales and subscales

Table 1 outlines the scales and subscales used in the survey, giving the number of items, possible range of responses, and Cronbach’s alpha for each.

Results of the Canadian Christian clergy resilience and well-being survey

In this section, we describe the participant-clergy demographics and the results from the various scales.

Participants

A total of 519 surveys were completed. Demographic questions inquired about the nature of the respondent, their context, and the congregation which they served. The sample included both males (74.2%) and females (25.2%). Please note that these percentages do not represent the Canadian population (49.6% male and 50.4% female), and there is no known parallel data on percentages for clergy in Canada. We do know that the largest Christian group is Roman Catholic, and its priests are all male. Anecdotally, mainline Protestants appear to have more female clergy than do conservative Protestants.

Participants in the survey were mostly older; the largest age group was 40 to 59 years old (50.3%), followed by 60 years and older (32.2%) and then 39 years old and younger (17.4%). The majority of participants indicated they were married (76.9%) and had children (74%). There is no known source of Canadian data to indicate where or not these demographic percentages differ from the general population of clergy in Canada.

Congregational questions inquired about the community, type of current congregation, average attendance of current congregation, and level of congregational flourishing. The results are reported in Table 2.

Participants’ employment varied: full-time (77.3%), half-time or greater (14.5%), less than half-time (7.5%), and bivocational (28.9%). The context where clergy participants ministered were reported as church context (67.8%), multiple contexts (11.2%), denomination (10.4%), chaplaincy (4.4%), and parachurch (2.3%).

Participants were from a wide variety of Christian traditions, including Catholic (12.1%) and Orthodox (2.1%). Participants also included those from mainline Protestant traditions (32.8%), including Anglican, Lutheran, Presbyterian, and United Church of Canada. The remainder of participants (53%) were from various traditions, most of which are within the conservative Protestant tradition. Note that there are no known comparative data to help us know whether the demographics in this paragraph differ from general population of clergy (with respect to terms of employment or context of ministry. The participant representation with respect to three traditions (Catholic, mainline Protestant, and conservative Protestant) is inverse to the Canadian adherent populations; however, a further study might find that clergy roles and clergy-to-parishioner ratios vary according to tradition, definition, and other contextual factors.

Health status scales

The first health status scale was a one-item scale asking participants about their current health today. Clergy participants had a mean response of 75.6, and a standard deviation of 16.5. The second health status scale was a 5-item scale about health in general. The mean response for this scale was 19.3, with a standard deviation of 3.9. Figure 1 illustrates the breakdown of responses for the five questions.

The final health status scale was an 8-item scale assessing holistic well-being and overall sense of wellness. Out of a possible cumulative score ranging from 8 to 40, participants’ mean response was 29.6, with a standard deviation of 4.9. Figure 2 illustrates the breakdown of responses for the eight domains in the wellness satisfactions scale.

MANOVA analysis, Wilks’ lambda, and Pillai’s multivariate tests were conducted to compare the health scales and the personal and congregational demographics. Three statistical differences were found. First, significant differences were found in participants who did not feel that their congregation/parish was flourishing (M = 69.7, SD =19.5); they had lower levels of health (F(2, 344) = 5.8, p = 0.003) compared to those who felt their congregation was flourishing (M = 77.7, SD =15.3).

Second, statistical differences were found for those who reported over 30 years of ministry experience (M = 28.6, SD 5.2). They had significantly lower wellness satisfaction scores (F(3, 515) = 3.4, p = .018) than those who had 11–20 years of ministry experience (M = 30.5, SD 4.4). Third, statistically different responses for the health today scale were related to age and years in ministry. Further regression analysis of age (F(10, 507) = 11.6, p < .001) and years in ministry (F(10, 508) = 6.5, p < .001) revealed that age (14.5%) had a more significant impact on health today scores than years of ministry (9.5%).

Professional quality of life scale

The Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale measured the dimensions of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue. A number of ProQOL statements from the compassion satisfaction subscale received high ratings. For example, many clergy participants (85.9%) indicated that they could make a difference through their work as clergy; got satisfaction from being able to help people (85.8%); liked their work as clergy (89.6%); and were happy that they had chosen to do this work (90.4%). All of these questions contributed towards the compassion satisfaction scale. Based on respondents’ high scores on the compassion satisfaction subscale, it would seem that participants experienced an elevated level of compassion satisfaction. Responses to all statements used in the compassion satisfaction subscale are illustrated in Fig. 3 below.

Most participants (94.8%) reported that they had beliefs that sustained them. Responses to all statements used in the burnout subscale are illustrated in Fig. 4 below.

The ProQOL cut points did not flag any areas of concern related to burnout or secondary trauma. Few clergy participants indicated that the following statements from the secondary traumatic stress subscale were “very much” or “mostly” like them: “As a result of my experience helping others, I have intrusive, frightening thoughts” (2.7%); “I feel as though I am experiencing the trauma of someone I have helped” (4.2%); “I avoid certain activities or situations because they remind me of the frightening experiences of the people I have helped” (4.3%) and “I feel depressed because of the traumatic experiences of the people I’ve helped” (4.3%). The lower scores on the secondary traumatic stress subscale provide evidence of the low levels of secondary trauma. The secondary traumatic stress findings suggest that the nature of adversity clergy experience may be more everyday adversity rather than trauma-related adversity that results in secondary traumatic stress. Responses to all statements used in the secondary traumatic stress subscale are illustrated in Fig. 5 below.

MANOVA analysis of the ProQOL results based on the personal and congregational demographics did not reveal any statistical differences among groupings. There were small variances in ProQOL transformed means based on demographic variables; however, none were above or below the cut scores to indicate high or low compassion satisfaction, burnout, or secondary trauma. Multivariate tests were conducted on the ProQOL scores, and no areas of statistical difference were found.

Ego-resiliency scale

Possible cumulative scores for the Ego-Resiliency scale could range from 0 to 56. The mean response from participants for the Ego-Resiliency scale was 45.0, with a standard deviation of 4.9. The participants’ overall level of ego-resiliency is measured by summing the scores and then interpreting them by categories (very high, high, undetermined, low, and very low). The mean score indicated that the survey participants had high resiliency trait.

The MANOVA analysis and Pillai’s score were conducted to compare the Ego-Resiliency scores of participants who had a mentor to those who did not. Significant differences were found in the Ego-Resiliency scores (F(1, 517) = 14.0, p < .001), whereby those participants with a mentor had higher Ego-Resiliency scores (M = 46.0, SD = 4.8) than those without a mentor (M = 44.4, SD = 4.8). In addition, further analysis using Wilks’ lambda (F(14, 1008) = 1.8, p = 0.034) and univariate test (F(2, 510) = 4.0, p = .019) showed that the impact of mentoring on the Ego-Resiliency scores was related to participants’ marital status. Specifically, significant differences were found in those participants who were married or common-law (t(398) = −4.4, p < .001), whereby those with a partner and a mentor had higher Ego-Resiliency scores (M = 46.4, SD 4.8) than those who had a partner but did not have a mentor (M = 44.1, SD 4.8). Finally, participants who reported that their congregation was flourishing (F(2,344) = 5.9, p = .003) had statistically higher Ego-Resiliency scores (M = 45.4, SD 4.7) compared to those who not feel their congregation was flourishing (M = 42.9, SD 5.2).

Grit-S scale

MANOVA analysis and Pillai’s multivariate tests were conducted to compare the Grit-S scores and the personal and congregational demographics. There were several statistical differences in relation to the Grit-S scores. First, participants who agreed with the statement that their congregation was flourishing (M = 3.7, SD 0.6) had significantly higher Grit-S scores (F(2, 344) = 6.3, p = .002) than those who disagreed with the statement (M = 3.4, SD .6). Second, participants who live less than 25 km from family support had significantly higher Grit-S scores (F(1, 511) = 6.2, p = .013) if they did not currently have a mentor (M = 3.7, SD .6) compared to those who did currently have a mentor (M = 3.5, SD .6).

Third, participants reporting 30+ years in ministry (M = 3.8, SD .5) had significantly higher Grit-S scores (F(3, 515) = 7.0, p < .001) than those with less than 10 years (M = 3.5, SD .7), those with 11–20 years (M = 3.6, SD 0.6), and those with 21–30 years (M = 3.5, SD .6). Finally, participants 70 years and older (M = 3.9, SD .5) had statistically higher Grit-S scores (F(4, 513) = 7.1, p < .001) than those under 40 (M = 3.4, SD .7), those 40–49 (M = 3.47, SD .688), and those 50–59 (M = 3.61, SD .573). Further regression analysis of age (F(10, 507) = 11.6, p < .001) and years in ministry (F(10, 508) = 6.5, p < .001) revealed that age (18.0%) had a more significant impact on Grit-S than years of ministry (14.3%).

Cantril Ladder

In response to the Cantril question about current satisfaction, there was a mean response of 8.3 (SD 1.6) for current satisfaction out of a possible 10. There was a mean response of 9.1 (SD 1.6) out of a possible 10 for sense of future satisfaction. These responses indicate that participants currently see themselves as near their best possible life and that they anticipate this will improve even more in the next five years.

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the responses to the two Cantril questions.

MANOVA analysis and Wilks’ lambda and Pillai’s multivariate tests were conducted to compare the Cantril scores and the personal and congregational demographics. Several areas showed statistical difference in relation to the Cantril scores. First, participants who lived more than 25 km from their personal support (M = 8.0, SD 1.7) scored significantly lower on the Cantril question about current satisfaction (F(1, 511) = 8.5, p = .004) than those who lived less than 25 km from their personal support (M = 8.4, SD 1.5).

Second, participants who had over 30 years of ministry experience (M = 8.7, SD 1.5) reported higher scores on current satisfaction (F(3, 515) = 6.3, p < .001) than those with 10 or less years of ministry experience (M = 7.9, SD 1.8), those with 11–20 years (M = 8.1, SD 1.6), and those with 21–30 years (M = 8.2, SD 1.3).

Third, participants 60 years old or older reported significantly higher scores on the Cantril question about current satisfaction (F(4, 513) = 10.3, p < .001) than those younger than 60. Table 3 shows the different comparisons among the age groupings.

Further regression analysis of age (F(10, 507) = 11.6, p < .001) and years in ministry (F(10, 508) = 6.5, p < .001) revealed that age (32.1%) had a more significant impact on current Cantril scores than years in ministry (22.1%).

Fourth, scores for Cantril questions about current satisfaction were significantly lower (F(2, 344) = 12.4, p < .001) for those who disagreed (M = 7.38, SD1.84) with the statement that their congregation was flourishing than for those who agreed (M = 8.5, SD 1.4) or neither agreed nor disagreed that their congregation was flourishing (M = 8.3, SD 1.3). Fifth, the future Cantril question scores about anticipated satisfaction five years from now were significantly lower (F(2, 344) = 12.9, p < .001) for those who disagreed (M = 8.3, SD 1.8) with the statement that their congregation was flourishing than for those who agreed (M = 9.4, SD 1.4) or neither agreed nor disagreed that their congregation was flourishing (M = 9.0, SD 1.8).

Discussion of results

This study adds essential insights into the overall health and well-being of Canadian Christian clergy as very little was previously known. These findings are unique in providing a comprehensive evaluation of health and well-being. Despite the survey occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic, with increased workload, social distancing requirements, and concern for church finances, participants’ mean responses indicated satisfaction with their physical, mental and holistic health and a general lack of present health concerns. Participants’ mean responses also indicated that clergy were doing well in terms of resilience and well-being, with high ego-resiliency and grit and low levels of burnout.

These findings are in contrast to Proeschold-Bell et al.’s (2015) argument that decreasing social isolation and financial stress are important for clergy well-being. The pandemic likely increased both factors for participants, yet their scale responses indicate a moderate level of well-being. However, Proeschold-Bell et al. (2015) and Malcolm et al. (2019) emphasized the role of both stressors and satisfiers in clergy mental health. While there were increased stressors due to the pandemic, perhaps there were also hidden increased satisfiers, such as increased time for personal spiritual practices. Further, Malcolm et al. (2019) emphasized that the absence of stress does not equate to wellness.

The findings from this study suggest that the presence of stress does not equate to poor well-being as clergy responded to stress with resilience. Conducting this study in the midst of COVID-19 provided a real-life example of clergy response to adversity. Despite the effects of COVID-19, the data indicated an overall sense of resilience among the clergy participants. Further research is needed to understand the interplay of clergy stressors and satisfiers and their impact on well-being and resilience.

This study has significance in identifying age and congregational flourishing as two factors that resulted in a statistical difference in clergy responses. First, age was a factor that impacted three scale responses. Participants who were 70+ years old had higher Grit-S scores than all other age groups. Age also impacted Cantril scores, with those participants 60+ reporting higher current satisfaction than those who were younger. However, older participants had lower health today scores. These data showed that increased age was associated with positive outcomes for clergy in the areas of grit and sense of current and anticipated life satisfaction but less holistic wellness satisfaction and suggested that clerics need different supports based on their age and development.

Second, participants’ sense of their congregation flourishing impacted their overall health score, Ego-Resiliency score, Grit-S score, and Cantril scores. The Thiessen et al. (2019) study on Canadian congregations highlighted the challenge of defining what constitutes flourishing and concluded that “perception shape reality” (p. 33). The perception of congregational flourishing seems to shape the well-being of clergy. Participants who indicated their congregation was flourishing had higher overall health, Ego-Resiliency, and Grit-S scores. The Cantril present and future life satisfaction scores were also statistically higher for those participants who agreed that their congregation was flourishing. The connection between clergy well-being and resilience and the perception that their congregation is flourishing needs further investigation as it may be that clergy who do not perceive that their congregation is flourishing need extra supports. Understanding the interplay between perceptions of congregational flourishing and clergy well-being is important for those who provide care and support to clergy.

Limitations and future research

Given the all-encompassing limitation that this research occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, further inquiry following the pandemic to confirm consistency of the scores is important. While the mean survey scale scores indicated participants were doing well, some individual participants’ scores indicated that they were not doing as well. The diversity of responses may point to the varying levels of adversity different clerics were experiencing.

The impact of congregational flourishing on clergy wellness was found to be significant on the overall health, Ego-Resiliency, Grit-S, and Cantril scores. As such, further investigation into the connection between congregational flourishing and clergy resilience and wellness is warranted. Further understanding of the impact of diverse theological perspectives and also the impact of moral distress and resilience on clergy resilience is needed.

Conclusion

This study found that clergy well-being and resilience were relatively strong despite the increased adversity of the COVID-19 pandemic. The nature of their current resilience and well-being included high levels of ego-resiliency and satisfaction with health and wellness, as well as moderate grit levels. There were no concerns flagged related to burnout or secondary trauma. Other significant findings included the impact of congregational flourishing and age on clergy well-being and the implications this may have for providing targeted support based on these factors.

Notes

A copy of the Grit-S is available here: http://www.sjdm.org/dmidi/files/Grit-8-item.pdf.

References

Abernethy, A. D., Grannum, G. D., Gordon, C. L., Williamson, R., & Currier, J. M. (2016). The Pastors Empowerment Program: A resilience education intervention to prevent clergy burnout. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 3(3), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000109

Avis, P. (1992). Authority, leadership and conflict in the church. Trinity Press International.

Block, J., & Kremen, A. M. (1996). Ego-Resiliency Scale [Datebase record]. APA PsychTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01072-000

Burckhardt, C. S., & Anderson, K. L. (2003). The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): Reliability, validity, and utilization. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1(60), 1–7.

Burt, S. (1988). Activating leadership in the small church: Clergy and laity working together. Judson Press.

Clarke, M. A. (2021). Understanding clergy resilience: A mixed methods research study. Doctoral dissertation, University of Saskatchewan. https://hdl.handle.net/10388/13496

Coate, M. A. (1989). Clergy stress: The hidden conflicts in ministry. SPCK.

Cornelissen, L. (2021). Religiosity in Canada and its evolution from 1985 to 2019. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2021001/article/00010-eng.htm

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the short Grit scale (Grit-S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

Ershova, M., & Hermelink, J. (2012). Spirituality, administration, and normativity in current church organization. Journal of Practical Theology, 16(2), 221–242.

EuroQol Research Foundation. (2019). EQ-5D-5L User Guide. Available from https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/

Grudem, E. (2016). Pour it out: God doesn’t intend pastors to burn out. There’s a better way. Leadership, 32–36.

Kilpatrick, F. P., & Cantril, H. (1960). Self-anchoring scaling: A measure of individuals’ unique reality worlds. Journal of Individual Psychology, 16(2), 158–173.

Malcolm, W. M., Coetzee, K. L., & Fisher, E. A. (2019). Measuring ministry-specific stress and satisfaction: The psychometric properties of the positive and negative aspects inventories. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 47(4), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091647119837018

Malony, H. N., & Hunt, R. A. (1991). The psychology of clergy. Morehouse Publishing.

Mazur, J., Szkultecka-Dębek, M., Dzielska, A., Drozd, M., & Małkowska-Szkutnik, A. (2018). What does the Cantril Ladder measure in adolescence? Archives of Medical Science, 14(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.60718

Means, J. E. (1989). Leadership in Christian ministry. Baker Book House.

OECD. (2013). OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264191655-en

Oswald, R. M., & Johnson, B. (2010). Managing polarities in congregations: Eight keys for thriving faith communities. Rowman & Littlefield.

Proeschold-Bell, R. J., Eisenberg, A., Adams, C., Smith, B., Legrand, S., & Wilk, A. (2015). The glory of God is a human being fully alive: Predictors of positive versus negative mental health among clergy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 54(4), 702–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12234

Stamm, B. H. (2010). The concise ProQOL manual. https://jpo.wrlc.org/bitstream/handle/11204/4293/The Concise Manual for the Professional Quality of Life Scale.pdf?sequence=1

Statistics Canada. (2021). Religion in Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2021079-eng.htm

Stoffel, J. M., & Cain, J. (2018). Review of grit and resilience literature within health professions education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 82(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe6150

Thiessen, J., Wong, A., McAlpine, B., & Walker, K. (2019). What is a flourishing congregation? Leader perceptions, definitions, and experiences. Review of Religious Research, 61(1), 13–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-018-0356-3

Windle, G., Bennett, K. M., & Noyes, J. (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-8

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our colleagues, Professors Vicki Squires and Paul Newton, who provided advice for this research. We would also like to acknowledge Flourishing Congregations Institute, The Christian and Missionary Alliance, and Canadian Church of God Ministries for partnering in the study by sending the survey directly to their clergy contacts. Finally, we would like to acknowledge those clergy who participated in this survey and provided important insight into their well-being and resilience.

Funding

The survey hosting and analysis costs were supported by the Flourishing Congregations Institute, The Canadian Hub for Applied and Social Research (CHASR) at the University of Saskatchewan and funded by a Social Sciences Humanities Research Canada (SSHRC) grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Board of the University of Saskatchewan.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The author has no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Clarke, M., Spurr, S. & Walker, K. The Well-Being and Resilience of Canadian Christian Clergy. Pastoral Psychol 71, 597–613 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-022-01023-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-022-01023-1