Abstract

Our paper addresses the following question: Is there a general characterization, for all predicates P that take both declarative and interrogative complements (responsive predicates in the sense of Lahiri’s 2002 typology, see Lahiri, Questions and Answers in Embedded Contexts, OUP, 2002), of the meaning of the P-interrogative clause construction in terms of the meaning of the P-declarative clause construction? On our account, if P is a responsive predicate and Q a question embedded under P, then the meaning of ‘P + Q’ is, informally, “to be in the relation expressed by P to some potential complete answer to Q”. We show that this rule allows us to derive veridical and non-veridical readings of embedded questions, depending on whether the embedding verb is veridical or not, and provide novel empirical evidence supporting the generalization. We then enrich our basic proposal to account for the presuppositions induced by the embedding verbs, as well as for the generation of intermediate exhaustive readings of embedded questions (Klinedinst and Rothschild in Semant Pragmat 4:1–23, 2011).

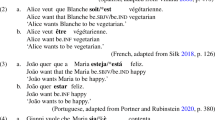

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We don’t know yet of a comprehensive account of embedded questions within the framework of Inquisitive Semantics (see Ciardelli et al. 2013 for a survey). However, Ciardelli and Roelofsen (this issue) provide a treatment of embedding of declaratives and interrogatives under an epistemic operator representing knowledge, as well as under wonder, within the framework of Inquisitive Semantics. See also Theiler (2014) and Roelofsen et al. (2014).

The exception is George (2011), who partly builds on the ideas we present here. Though we do not discuss George’s specific proposal, many aspects of the second half of our paper are related to George’s work.

We use here semi-formal lexical entries. This is meant only for illustration.

We are indebted to J. Groenendijk for this comment.

But see (George 2011 pp. 142–169) for a discussion of such issues.

The case of “decide” is not in Lahiri’s original list. In Egré (2008), decide is treated as a responsive non-veridical predicate.

Let us make our terminology clear (though still informal):

-

a predicate P is veridical-responsive if it can take an interrogative clause Q as one of its argument and is such that [X P Q] (where X is an other argument of P, if P requires one, the null string otherwise) is true if and only if [X P S] is true, where S expresses the actual complete answer to Q.

-

a predicate P is factive with respect to its declarative complements if it can take a declarative clause S as one of its arguments and is such that [X P S] presupposes that S is true.

-

a predicate P is veridical with respect to its declarative complements if it can take a declarative clause S as one of its arguments and is such that [X P S] entails that S is true.

Assuming that any presupposition of a sentence is also an entailment of this sentence, it follows that a predicate that is factive with respect to its declarative complement is always also veridical with respect to its declarative complement. Note that the generalization that all veridical-responsive predicates are also veridical with respect to their declarative complements is by no means a logical necessity (it has actually been explicitly denied, as we will see)

-

It will turn out that all such predicates are actually factive, and not merely veridical, with respect to their declarative complements, a fact that will become crucial in Sect. 5.

Strikingly, the question “Did Sue say that she is pregnant?” does not seem to suggest that Sue is in fact pregnant, at least not to the same extent as (29). According to some informants if a dative argument is added for the verb ‘say’ (“Did Sue say to anyone that she is pregnant?”), then the question is more easily understood as implying that Sue is pregnant, but still not to the same extent as (29).

An anonymous reviewer suggests that the verb ‘suspect’ likewise may have both a factive and a non-factive use, but is not in any clear sense a ‘communication verb’. The same appears to hold of ‘guess’ in English (see Egré 2008). ‘Guess’, like ‘suspect’, is not a communication verb ; unlike ‘guess’, however, ‘suspect’ does not appear to license embedded questions.

While deviner has to take an animate, sentient subject, prédire, just like English predict, can take any subject whose denotation can be conceptualized as carrying some kind of propositional information. Thus, a linguistic theory can predict a certain fact, and the French counterpart of the phrase ‘This theory’ can be the subject of prédire, but not of deviner.

This is a subtle contrast. There are uses of prédire which do not imply a speech act, as when one says that a theory predicts something. But it is at least true that, out of the blue, a sentence with prédire is understood to imply the presence of a speech act.

We are not committed to the view that each responsive predicate really comes in two variants in the lexicon. Rather, one has to be derived from the other by some type-shifting rule. As is well known (Groenendijk and Stokhof 1982), responsive predicates can take as a complement a coordinate clause made up of a declarative clause and an interrogative clause (John knows that Peter attended the concert and whether he liked it), which suggests that the correct account should not rely on the assumption that the ambiguity is located in the responsive predicate itself. It should be possible to define a type-shifter that would apply to the interrogative clause itself, licensing it as a complement of verbs or predicates of attitude, as in Egré (2008), which is based on similar ideas as this paper (however, it is not entirely clear how the facts we discuss in Sect. 4 about presupposition projection, and our proposal developed in the final sections regarding the ambiguity between weakly/intermediate and strongly exhaustive readings can be straightforwardly accommodated in these terms). Another possible approach, discussed by Jeroen Groenendijk in an extensive review of the present paper, would consist in moving to a framework where declarative and interrogative sentences have the same semantic type. We do not discuss these issues in this paper. We choose (for simplicity) to present our proposal in terms of a lexical rule (a meaning postulate) that defines the meaning of the interrogative-taking variant of a responsive predicate in terms of the meaning of its declarative-taking variant, with the hope that the gist of our proposal can be captured in such alternative frameworks.

We adopt an intensional semantics framework in which all expressions are evaluated with respect to a world, but nothing in this paper hinges on this choice. Throughout the paper, we adopt Heim and Kratzer’s (1998) and von Fintel and Heim’s (2011) notational conventions. Later in this paper, as we will introduce several notions of complete answers, our rules will take a slightly different form.

That view is argued for in Egré (2008), where the non-veridicality of responsive predicates also taking declarative complements is attributed to the presence of overt or covert prepositions.

This view is endorsed by Higginbotham (1996) in particular, who presents it as a reason not to adopt an existential semantics for questions (such as the one we endorse here).

In particular, we do not discuss in this paper the ambiguity between the de re and de dicto readings of wh-phrases in embedded questions. We are only considering contexts where the denotation of the restrictor is common knowledge, in which case the two readings collapse.

There is another notion of complete answer that one might consider, according to which the complete answer is not defined when the basic complete answer is a tautology. This would correspond to a claim that wh-questions carry an existence presupposition, an issue that has been much discussed (see, e.g., Dayal 1996). We do not want to endorse this claim and do not discuss this option further in this paper—except in footnotes 34 and 38.

Proof of (76)b. First, unless \({\upphi }\) is tautologous,

by definition.

by definition.If \(\upphi \) is tautologous then

.

.We also have:

. Symmetrically with \(\lnot {\upphi }\). (76)a. follows straightforwardly.

. Symmetrically with \(\lnot {\upphi }\). (76)a. follows straightforwardly.Namely, if \(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {w}) = 1\), then p = Q(w) and \(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}) = \hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {Q(w)})\). Proof: assume \(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {w}) = 1\). Then by definition \({\uplambda }\hbox {v}(\hbox {Q(v)} = \hbox {p})(\hbox {w}) = 1\), i.e. Q(w) \(=\) p.

The assertive meaning of know is in fact stronger, see Gettier (1963)’s classic arguments, but this point is not relevant for what follows.

We use Heim and Kratzer’s (1998) notation for representing presuppositions in our lexical entries. Namely, a lexical entry of the form \([\![\hbox {X}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}={\uplambda }\hbox {A}.\,\ldots \,.{\uplambda }\hbox {Z}:\, \phi (\text {A}\ldots \ldots ,\text {Z}).\varPsi (\text {A}\ldots \ldots ,\text {Z})\), where X has a type that ‘ends in t’, means that X denotes a function which, when fed with arguments \(\text {A},\dots ,\text {Z}\) of appropriate types, is defined only if \(\phi (\text {A}\ldots \ldots ,\text {Z})\) is true, and, when defined, returns the value 1 if and only if \(\varPsi (\text {A}\ldots \ldots ,\text {Z})\) holds. In other words, the presuppositions triggered by an expression are encoded in the part of the formula standing between the column and the period. We will often call the right-hand side of such expressions the ‘assertive part’ of an expression, but this is in fact improper, as discussed in footnote 31.

In the first version of our proposal, we did not take note of the fact that we predicted a reading that was stronger than what the previous literature had assumed. Chemla and George’s recent survey prompted us to revisit our proposal. Many thanks to Ben George and Alexandre Cremers for extremely useful discussions.

Presupposition-driven domain restriction yields the consequence that John agrees with Mary on which students came and Mary agrees with John on which students came may have a different truth-value. The first sentence will mean For every student about whom Mary has an opinion, John has the same opinion, and this does not entail that for every student about whom John has an opinion, Mary has an opinion. Such an asymmetry, which is also predicted by Lahiri (2002), was not detected in Chemla and George’s survey.

Assuming that A and B agree that \({\upphi }\) should be analyzed as equivalent to A and B agree with each other that \({\upphi }\), one would need to derive this presupposition from the meaning of agree with, the reciprocal construction, and general principles of presupposition projection. This is far from trivial. If we analyze such sentences are equivalent to A agrees with B that \({\upphi }\) and B agrees with A that \({\upphi }\), given that X agrees with Y that \({\upphi }\) presupposes that Y believes that \({\upphi }\), we expect that A and B agree that \({\upphi }\) will presuppose that both A and B believe \({\upphi }\), clearly a wrong result (because then such sentences could not be false, only true or undefined). This problem was noted by Lahiri. Just like us, Lahiri suggests a disjunctive presupposition ‘either A or B believe that \({\upphi }\)’.

See George (2011) for an extensive discussion. George concludes that neither the weakly exhaustive reading nor the intermediate reading exists for know. Results from recent experimental surveys do not support this conclusion (Klinedinst and Rothschild 2011 report the results of such a survey for the verb predict, but not know, and Cremers and Chemla, to appear, provide more systematic evidence).

Lahiri (2002) briefly mentions a similar example, which he attributes to J. Higginbotham. Namely, the sentence John knows which numbers between 10 and 20 are prime cannot be true (on any conceivable reading) if John happens to believe that all numbers between 10 and 20 are prime.

As Groenendijk and Stokhof (1982) noticed, on the weakly exhaustive reading know does not satisfy positive introspection when it embeds an interrogative clause. That is, John can know who came without knowing that he knows who came. This is the case if for every \(x\) who came John knows that \(x\) came and for every \(y\) who didn’t come John has no idea whether \(y\) came.

Klinedinst and Rothschild (2011) argue that surprise can in fact give rise to strongly exhaustive readings. The important point for us is only the fact that a weakly exhaustive reading is clearly available (and seems in fact to be preferred). George (2011), on the other hand, argues that the weakly exhaustive reading does not exist with surprise, and that the cases that are used to claim otherwise are in fact instances of the mention-some reading. See our discussion in footnote 33.

The assumption that be surprising to X that S presupposes knowledge of \(S\) by \(X\) is not uncontroversial. Egré (2008) argues that so-called emotive factive predicates, like regret, are not in fact veridical, but involve only the weaker presupposition that X believes p. Here we choose to abide by the more standard assumption that surprise is indeed factive, and comes with a knowledge presupposition. Nothing essential hinges on this.

In a trivalent approach to presuppositions, there is no need to define a non-presuppositional ‘assertive component’ for a presuppositional expression. For instance, John knows that S denotes a partial function from worlds to propositions, such that the function is not defined for a world in which \(S\) is false. There is no non-arbitrary way (and no need) to extract from this partial function a complete function which would correspond to a non-presuppositional, bivalent ‘assertive’ component. This is so because there are many different ways of ‘completing’ a partial function, and so no non-arbitrary way to define such a non-presuppositional, bivalent proposition that would express the ‘assertive part’ of John knows that S. Of course, in our metalanguage, when we state the truth-conditional import of an expression, we need to make use (in the right-hand side of our rules) of a metalanguage statement which we can informally call the ‘assertive part’. This part tells us how to assign truth and falsity to a sentence whose presuppositions are satisfied, and there are many equivalent ways to formulate it which can look superficially very different. For instance, the three following (simplistic) lexical entries for know are fully equivalent:

-

(i)

\([\![\hbox {know}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}= {\uplambda }\hbox {p}. {\uplambda }\hbox {x}{:}\,\hbox {p(w)} = 1.\,\hbox {x}\) believes p in w

-

(ii)

\([\![\hbox {know}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}= {\uplambda }\hbox {p}. {\uplambda }\hbox {x}{:}\,\hbox {p(w)} = 1.\,\hbox {p(w)} = 0\) or x believes p in w

-

(iii)

\([\![\hbox {know}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}= {\uplambda }\hbox {p}. {\uplambda }\hbox {x}{:}\,\hbox {p(w)} = 1.\,\hbox {p(w)} = 1\) and x believes p in w

-

(i)

We contrasted the above scenario with a minimally different one in which Mary knows that A, B and C passed and that no other student passed. Our informants then had no problem with “It surprised Mary which of here ten students passed”. All our informants also reported a clear contrast between the two following discourses:

-

(i)

# John learnt that Peter and Sue passed. Mary and Alfred failed, but John didn’t learn that. It surprised him which of the four students passed.

-

(ii)

John knows that Peter and Sue passed and that Mary and Alfred failed. It surprised him which of the four students passed.

-

(i)

One could wonder whether a very weak semantics in terms of basic complete answers, of the type we rejected in Sect. 3.1, could be sufficient for surprise \(+\) wh-question. According to such a semantics, It surprised Mary which guests showed up would count as true as soon as there is a guest or a plurality of guests who showed up and such that the facts that this and these guests showed up surprised Mary. This is in fact a suggestion that George (2011) made. However, it seems to us that such a proposal is too weak, for at least two reasons. First, imagine that Ann only knows that Mary attended a certain party, and does not know that Jane and Sue did as well. Assume further that it surprised Ann that Mary attended the party. In such a situation, a very weak semantics of the form we rejected in Sect. 3.1 predicts that the sentence It surprised Ann which of the guests attended the party should be felicitous and true. But according to our informants, for the sentence to be felicitous, Ann has to know which guests attended the party. One possible fix would be to claim that at the presuppositional level the strong notion of complete answer is used, with the results that It surprised Ann which of the guests came would presuppose that Ann knows which of the guests came (in the strong sense) and that for some guests who came it surprised her that they came. According to our intuitions, however, there may be situations where Mary could be surprised that a specific guest showed up and yet fail to be surprised by which guests showed up. Imagine for instance the following situation: the fact that Peter showed up is surprising to Mary, but that the overall list of guests who showed up is not so surprising, despite Peter’s presence. In such a situation it is conceivable that one could say that it surprised Mary that Peter showed up, but not that it surprised her which guests showed up. Whether or not our intuition is robust, it is very possible that surprise is non-monotonic with respect to its complement, and we do not want our theory of question embedding to be dependent on too specific assumptions about the lexical semantics of surprise (such as the assumption that it surprised Mary that S entails it surprised Mary that S & T, which seems natural at first sight but might not be correct under closer scrutiny).

We may want such a sentence to actually count as a presuppositional failure in a situation where no guests showed up. See the Appendix, where this possibility is explored.

Note that in the presuppositional part we still use the basic notion of complete answer rather than Karttunen-answers. See the Appendix, where we discuss the possibility of not making use at all of basic complete answers.

If no guest showed up, the basic complete answer is the tautology and the presupposition that Mary did not know the basic complete answer is necessarily false.

Recall that we are using a trivalent theory of presuppositions where if a sentence is true, then its presuppositions are true as well.

There may be a tension between this prediction and the fact that for It surprised Mary who came, we do not predict presuppositional failure in case nobody came. See footnote 34 and our discussion in the Appendix.

For instance, repeating ‘\([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})\) is defined’ in the assertive part of the rule for strongly exhaustive readings generally has an effect for a predicate whose presuppositional content is not monotone increasing with respect to its complement. In particular, if P is presuppositionally monotone-decreasing, ‘\([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})\) is defined’ entails ‘\([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p})\) is defined’, and its addition is thus non-vacuous. We haven’t seen such a case yet. Even though discover is presuppositionally non-monotonic, the condition ‘\([\![\hbox {discover}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p})\) is defined’ is sufficient to force p to be the unique actual basic complete, because discover is factive.

As discussed in footnote 31, in a trivalent approach to presuppositions there is no intrinsic need to be able to extract a non-presuppositional ‘assertive’ part from a presuppositional expression, even though we informally referred to the right-hand side of our lexical rules as to an ‘assertive component’. Our lexical entries, which were of the form \({\uplambda }\hbox {x}.{\uplambda }\hbox {y}.\,\ldots \, .{\uplambda }\hbox {z}:\upvarphi (\hbox {x,y},\dots ,\hbox {z}).\Psi (\hbox {x,y}, \ldots ,\hbox {z})\), are just notational devices to describe partial functions, with the lefthand side specifying when the function is defined, and the righthand side specifying which value the function returns when it is defined.

We totally ignore here the fact that true belief is not sufficient to characterize knowledge. A more accurate characterization of the non-factive attitude associated with know may be believe on the basis of compelling subjective evidence. This however still runs into Gettier’s problem (Gettier 1963). Note that the idea that it is possible to extract from know a corresponding non-factive attitude has been argued to be intrinsically misguided on the basis of variations on Gettier’s problem—see in particular Williamson (2000).

Thanks to Alexandre Cremers for drawing our attention to this case.

One possibility that suggests itself would be to replace, in (127), the clause ‘such that p’ asymmetrically entails \(\hbox {p}'\) with ‘such that

, where \(\subset \) represents asymmetric entailment. This, however, doesn’t solve the problem for John forgot which guests showed up. Suppose, for instance, that in fact the people who came are John and Mary. Let us schematize ‘John and Mary came’ by j & m. Now note that X forgot j entails X forgot j & m, and so does X forgot m (in this case, whether or not we consider only the assertive part or include the presupposition does not matter). Then with the modified clause, (127) would result in the following truth conditions (when the people who came are John and Mary) for Peter forgot who came: Peter forgot j & m but neither forgot \(j\) nor forgot \(m\), which is clearly contradictory.

, where \(\subset \) represents asymmetric entailment. This, however, doesn’t solve the problem for John forgot which guests showed up. Suppose, for instance, that in fact the people who came are John and Mary. Let us schematize ‘John and Mary came’ by j & m. Now note that X forgot j entails X forgot j & m, and so does X forgot m (in this case, whether or not we consider only the assertive part or include the presupposition does not matter). Then with the modified clause, (127) would result in the following truth conditions (when the people who came are John and Mary) for Peter forgot who came: Peter forgot j & m but neither forgot \(j\) nor forgot \(m\), which is clearly contradictory.Klinedinst and Rothschild derive the no-false belief constraint by applying an exhaustivity operator to the V\(+\)Q constituent. Very informally, the idea is this: ‘X V Q’ is true if, (a) X is in the relation V to the actual basic complete answer to Q—call it A and (b) the exhaustification of the proposition ‘X V A’ relative to alternative propositions of the form X V B, where B can be any potential complete answer to Q, is true as well. Because exhaustification is defined in such a way that only innocently excludable alternatives in Fox’s (2007) sense are negated, it can never result in a contradiction. This approach can presumably be adapted to our own framework.

We do not take a stand as to whether surprise is non-monotonic with respect to its complement or monotone decreasing. Let us note that if surprise is treated as monotone-decreasing with respect to its complement (for instance by stating that p is surprising to X if and only \(X\) assigned \(p\) a probability lower than some threshold before \(X\) learnt \(p\)), Klinedinst and Rotschild’s proposal runs into a problem. It predicts that it surprised Mary who came is true if (a) Mary was surprised that the people who came and (b) for any subplurality of the people who came, Mary was not surprised that this plurality came. For instance, if the people who came are \(a,\,b\), and \(c\), Mary has to be surprised that \(a\) and \(b\) and \(c\) came, but not that \(a\) and \(b\) came, not that \(a\) and \(c\) came and not that \(b\) and \(c\) came. This prediction does not seem correct to us. Klinedinst and Rothschild thus need to assume that surprise is in fact non-monotonic (which we think might well be true). Thanks to Nathan Klinedinst for relevant discussions.

Egré (2008)’s proposal adopts a strategy that is in fact symmetric to the one adopted here : the default meaning for all embedded questions is assumed to be veridical, and the existential meaning associated to non-veridical readings is derived by means of a semantic operation that takes place only if the embedded interrogative is the sister of a preposition.

References

Beck, S., & Rullman, H. (1999). A flexible approach to exhaustivity in questions. Natural Language Semantics, 7, 249–298.

Berman, S. (1991). The semantics of open sentences, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Massachusetts.

Ciardelli, I. (2009). Inquistive semantics and intermediate logics. Master Thesis, University of Amsterdam.

Ciardelli, & Roelofsen, F. (2009). Generalized inquisitive logic: Completeness via intuitionistic Kripke models. Proceedings of Theoretical Aspects of Rationality and Knowledge.

Ciardelli, I., & Roelofsen, F. (2011). Inquisitive logic. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 40(1), 55–94.

Ciardelli, I., & Roelofsen, F. Inquisitive dynamic epistemic logic. To appear in Synthese, 1–45.

Ciardelli, I., Groenendijk, J., & Roelofsen, F. (2013). Inquisive semantics : A new notion of meaning. Language and Linguistics Compass, 7(9), 459–476.

Chemla, E., & George, B. (2014). Can we agree about agree?.

Cremers, A., & Chemla, E. (2014). A psycholinguistic study of the exhaustive readings of embedded questions. Journal of Semantics, ffu014. Ms. Available at http://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/DU3YWU2M/cremerschemla-semarch.html.

Dayal, V. (1996). Locality in WH quantification: Questions and relative clauses in Hindi. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Egré, P. (2008). Question-embedding and factivity. Grazer Philosophische Studien, 77(1), 85–125.

von Fintel, K. (2004). Would you believe it? The king of France is back! (Presuppositions and truth-value intuitions). In M. Reimer & A. Bezuidenhout (Eds.), Descriptions and beyond (pp. 315–341). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fintel, K., & Heim, I. (2011). Lecture notes in intensional semantics, Ms., MIT. Available at http://mit.edu/fintel/fintel-heim-intensional.pdf.

Fox, D. (2007). Free choice disjunction and the theory of scalar implicatures. In U. Sauerland & P. Stateva (Eds.), Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics (pp. 71–120). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fox, D. (2013). Classnotes on mention-some readings., Ms., MIT, Available at http://web.mit.edu/linguistics/people/faculty/fox/class1-3.pdf.

Gajewski, J. (2005). Neg-raising: Polarity and presupposition, PhD Dissertation, MIT.

George, B. (2011). Question embedding and the semantics of answers, PhD Dissertation, UCLA.

Gettier, E. (1963). Is justified true belief knowledge. Analysis, 121–123.

Groenendijk, J. (2009). Inquisitive semantics: Two possibilities for disjunction. In P. Bosch, D. Gabelaia, & J. Lang (Eds.), Seventh Tblisi symposium on language, logic and computation. Heidelberg: Springer.

Groenendijk, J., & Roelofsen, F. (2009). Inquisitive semantics and pragmatics. Presented at the workshop on Language, Communication and Rational Agency, Stanford. URL www.illc.uva.nl/inquisitivesemantics.

Groenendijk, J., & Stokhof, M. (1982). Semantic analysis of Wh-complements. Linguistics and Philosophy, 5, 117–233.

Groenendijk, J., & Stokhof, M. (1984). Studies on the semantics of questions and the pragmatics of answers. PhD Thesis. University of Amsterdam.

Groenendijk, J., & Stokhof, M. (1993). Interrogatives and adverbs of quantification. In K. Bimbo & A. Mate (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th symposium on logic and language.

Groenendijk, J., & Stokhof, M. (1997). Questions. In J. van Benthem & A. ter Meulen (Eds.), Handbook of semantics. Elsevier.

Guerzoni, E. (2007). Weak exhaustivity and whether: A pragmatic approach. In T. Friedman & M. Gibson (Eds.), Proceedings of SALT (pp. 112–129). Ithaca: Cornell.

Guerzoni, E., & Sharvit, Y. (2007). A question of strength: On NPIs in interrogative clauses. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(3), 361–391.

Hamblin, C. L. (1973). Questions in Montague english. Foundations of Language, 41–53.

Heim, I. (1994). Interrogative Semantics and Karttunen’s semantics for know. In R. Buchalla & A. Mittwoch (Eds.), Proceedings of IATL 1 (pp. 128–144). : Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Heim, I., & Kratzer, A. (1998). Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Higginbotham, J. (1996). The semantics of questions. In S. Lappin (Ed.), The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hintikka, J. (1976). The semantics of questions and the questions of semantics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Karttunen, L. (1977). Syntax and semantics of questions. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1, 3–44.

Klinedinst, N., & Rothschild, D. (2011). Exhaustivity in questions with non-factives. Semantics and Pragmatics, 4(2), 1–23.

Lahiri, U. (2002). Questions and answers in embedded contexts., Oxford studies in theoretical linguistics Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1982). ‘Whether’ report. In Pauli, T., & al. (eds), Philosophical essays dedicated to L. Aqvist on his 50th Birthday, repr. in D. Lewis, Papers in Philosophical Logic, chap. 3, Cambridge Studies in Philosophy.

Mascarenhas, S. (2009). Inquisitive semantics and logic. MSc in Logic thesis. Amsterdam: Institute for Logic, Language, and Computation.

Preuss, S. (2001). Issues in the Semantics of Questions with Quantifiers, PhD dissertation, Rutgers.

Roelofsen, F. (2013). Algebraic foundations for the semantic treatment of inquisitive content. Syntehese, 190(1), 79–102. doi:10.1007/s11229-013-0282-4.

Roelofsen, F., Theiler, N., & Aloni, M. (2014). Embedded interrogatives : the role of false answers. Presented at the 7th questions in discourse workshop, Göttingen, Sept 2014.

Romoli, J. (2013). A scalar implicature-based approach to neg-raising. Linguistics and philosophy, 36(4), 291–353.

Sharvit, Y. (2002). Embedded questions and ‘De Dicto’ readings. Natural Language Semantics, 10, 97–123.

Schlenker, P. (2007). Transparency: An incremental theory of presupposition projection. In U. Sauerland & P. Stateva (Eds.), Presupposition and impicature in compositional semantics (pp. 214–242). New York: Palgrave.

Schlenker, P. (2010). Local contexts and local meaning. Philosophical Studies, 151, 115–242.

Spector, B. (2005). Exhaustive interpretations: What to say and what not to say. Unpublished paper presented at the LSA workshop on Context and Content, Cambridge, MA.

Spector, B. (2006). Aspects de la pragmatique des opérateurs logiques, PhD Dissertation, University of Paris 7.

Spector, B., & Egré, P. (2007). Embedded questions revisited: An answer, not necessarily the answer. Handout, MIT linglunch, Nov 8, 2007. Available at http://lumiere.ens.fr/~bspector/Webpage/handout_mit_Egre&SpectorFinal.pdf.

Theiler, N. (2014). A multitude of answers: Embedded questions in typed inquisitive semantics. MSc thesis, University of Amsterdam, supervised by M. Aloni and F. Roelofsen.

Tsohatzidis, S. L. (1993). Speaking of Truth-Telling: the View from Wh-complements. Journal of Pragmatics, 19, 271–279.

Tsohatzidis, S. L. (1997). More telling examples: A reply to Holton. Journal of Pragmatics, 28, 625–628.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received support from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Grants ANR-10-LABX-0087 IEC, ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL and ANR-14-CE30-0010-01 TriLogMean). We thank the editors of this special issue, Yacin Hamami and Floris Roelofsen, for their encouragement to submit our work, and for many helpful suggestions. We are grateful to the two reviewers of this paper for detailed and valuable comments, and in particular to Jeroen Groenendijk, whose extremely detailed and perspicuous comments contributed very significantly to the final version of our proposal. Special thanks go to Marta Abrusan, Emmanuel Chemla, Alexandre Cremers, Danny Fox, Benjamin George, Elena Guerzoni, Nathan Klinedinst, Daniel Rothschild, Savas Tsohatzidis, and to audiences at MIT (LingLunch 2007), Paris (JSM 2008), Amsterdam (2009), UCLA (2009), and the University of Maryland (2014). We also thank Melanie Bervoets, Heather Burnett, Nat Hansen and David Ripley for native speakers’ judgments in English. The research leading to these results has received support from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Grants ANR-10-LABX-0087 IEC, ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL and ANR-14-CE30-0010-01 TriLogMean).

Compliance with ethical standards

This research did not involve human or animal participants. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A version of the research reported here was first presented at the MIT LingLunch in 2007 and at the Journées de Sémantique et de Modélisation 2008 and in a detailed hand-out form (see Spector and Egré 2007). Our proposal has evolved very significantly since then.

Appendix: More on tautological basic answers

Appendix: More on tautological basic answers

There are various ways in which our proposal might be modified regarding its treatment of the special case where the actual basic complete answer is the tautology. In this appendix, we discuss three possible modifications of our proposal.

1.1 A. Eliminating any reference to basic complete answers

Note that our proposal makes use of three distinct notions of answers: basic complete answers, Karttunen-complete answers, and strongly exhaustive answers, where Karttunen-complete answers and basic complete answers only differ regarding the special case where the basic complete answer is the tautology. Now, we can wonder what would follow if we eliminated completely any reference to basic complete answers, i.e. if we used Karttunen answers only, even in the presuppositional part of our meaning postulates. In such a case we could simply define \(Q(w)\) differently, so that it would directly denote what is currently denoted by \(Kart_{Q}(Q(w))\). In other words, pot(Q) would now be identified to the set of potential Karttunen-complete answers, rather than that of basic complete answers. But instead of introducing new definitions, let us rather keep our definitions, in terms of which we can state the resulting proposal as follows:

-

(132)

Meaning postulate for both the strongly exhaustive and the intermediate readings (modified version #1)

\([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{strong/intermediate}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}} = {\uplambda }\hbox {Q}.{\uplambda }\hbox {x}{:}\,\exists \hbox {p} \in \hbox {pot(Q)}([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {Kart}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})\) is defined).

\(\exists \hbox {p}\in \hbox {pot(Q)}([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {Kart}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\mathbf{param}_{\mathbf{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})=1\)

& there is no \(\hbox {p}'\in \hbox {pot(Q)}\) such that

-

\(\hbox {p}'\subset \hbox {p}\)

-

-

where param is a variable that takes as its value either exh or Kart.

-

Now, compared to our ‘official’ proposal, this does not change anything for predicates which are ‘presuppositionally’ monotone-increasing, such as know, forget, and surprise (X knows that S presupposes \(S\), X forgets that S and It surprised X that S presuppose S and X knows/used to know S). In particular, we still predict that It surprised Mary who came, on the intermediate reading, is neither a presuppositional failure nor trivally false in case nobody came. That is, such a sentence will entail that if nobody came, Mary knows it and is surprised by that fact. The proposal however makes a difference for predicates which are presuppositionally non-monotone-increasing, such as discover (X discovers that S presupposes S and X did not believe S). Whereas on the ‘official’ proposal, as we discussed, John discovered who came is a presupposition failure if in fact nobody came, on this new proposal the sentence can be true if nobody came, provided John didn’t know at some point that nobody came and came to believe that nobody came. We tend to think that our ‘official’ proposal makes a better prediction, but, as pointed out by a reviewer, it might be problematic not to make parallel predictions for surprise and for discover. That is, one might think that if John discovered who came is a presupposition failure when nobody came, so should be It surprised John who came.

1.2 B. A presuppositional variant for the weakly exhaustive reading

Another possibility would be to introduce, only in the rule for the intermediate reading, a presupposition ensuring that the basic complete answer to which the agent is related via the relevant attitude is not the tautology. On such a view, the rule for the strongly exhaustive reading would remain the same as in our official proposal, but we could not state the rule for the intermediate reading in terms of just a change of ‘parameter’ in the assertive part of the rule. We would also distinguish both readings in terms of their presuppositional behavior. The rule for the intermediate reading would then be stated as follows:

-

(133)

Meaning postulate for the intermediate readings (modified version #2)

\([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{intermediate}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}} = {\uplambda }\hbox {Q}.{\uplambda }\mathrm{x}{:}\,\exists \mathrm{p} \in \hbox {pot(Q)}\) (p is not the tautology and \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})\) is defined).

\(\exists \hbox {p}\in \hbox {pot(Q)}\)(p is not the tautology and \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![~\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {x})=1\) & there is no \(\hbox {p}'\in \hbox {pot(Q)}\) such that

-

\(\hbox {p}' \subset \hbox {p}\)

-

-

-

If we adopt this proposal, both sentences John knows who came and It surprised John who came, on the intermediate reading, would presuppose that someone came. The fact that John knows who came is not judged to be a presuppositional failure, but is rather judged true, if nobody came and John knows that fact, would then be attributed to the availability of the strongly exhaustive reading (which would not trigger such a presupposition). It might also be expected that It surprised Mary who came would tend to be perceived as infelicitous if it is known that nobody came, given that the intermediate reading might be the preferred reading with surprise (in fact, Guerzoni and Sharvit 2007 argue that it is the only reading). Nothing would change for John discovered who came. It would still be predicted to be a presuppositional failure if nobody came, both on the intermediate and on the strongly exhaustive reading (cf. our discussion in Sect. 6).

1.3 C. A more radical move: eliminating any reference to Karttunen-complete answers

Recall the motivation for using Karttunen-complete answers rather than basic complete answers for the intermediate reading: we do not want to predict that John knows who came is true when nobody came and John has no belief whatsoever. But we may try to explain this intuition not in terms of the semantics of embedded questions, but in pragmatic terms. A potential motivation for using basic complete answers rather than Karttunen-complete answers has to to with verbs such as tell and predict on their non-veridical use, and with non-presuppositional question-embedding predicates such as be certain about. In a nutshell, we will show such a move allows us to predict an interesting generalization: on their non-factive, non-veridical uses, verbs like tell and predict only license a strongly exhaustive reading. And likewise a non-presuppositional predicate like be certain about is only compatible with the strongly exhaustive reading.

Let us first illustrate the generalization. For the sentence Mary is certain about which students came to be true, Mary must be certain about a certain strongly exhaustive answer. If she is only certain, say, that the students Sue and Al came and has no idea for others, the sentence is false. As for predict, a sentence such as (134) below entails that Mary made a complete prediction, in the sense that her prediction was interpreted as a claim about what the actual strongly exhaustive reading is [Of course Mary does not need to have explicitly predicted who would come and who would not come. She may have said ‘Mary and Peter will come’, which, as an answer to ‘Who will come’, is easily intepreted as implying that nobody besides Mary and Peter will come].

-

(134)

Peter predicted which of the four students would attend the party, but he proved wrong.

To see this, consider (134) uttered in the context described in (135) below:

-

(135)

-

a.

Scenario: Peter wondered who would attend a certain party among four students, John, Sue, Fred, and Mary. He predicted that John and Sue would go and made no prediction about the others – he actually said that he had no idea about Fred and Mary. In fact it turned out that neither John nor Sue attended the party.

-

b.

Sentence: Peter predicted which of the four students would attend the party, but he proved wrong.

-

a.

According to our informants, (135)b is false in such a scenario. We can contrast this scenario with another one where Peter made a complete, exhaustive prediction that turned out to be false.

-

(136)

-

a.

Scenario: Peter wondered who would attend a certain party among four students, John, Sue, Fred, and Mary. He predicted that John and Sue would go and that Fred and Mary would not. In fact the reverse turned out to be true: only Fred and Mary attended the party.

-

b.

Sentence: Peter predicted which of the four students would attend the party, but he proved wrong

-

a.

Even though the non-veridical use of predict is somewhat dispreferred for some speakers, there is a very clear contrast between (135) and (136), in that (136), unlike (135), can be judged true. This shows that the non-veridical use of predict, which may be less salient than its veridical use, is in any case only compatible with the strongly exhaustive reading.

It turns out that this state of affairs is easy to predict if we adopt the proposal in (137) instead of our official proposal, whereby the intermediate reading is defined with no reference to Karttunen-complete answers (note that this proposal is essentially what you get if you add to (113) the clauses that take care of the ‘no-false belief’ constraint).

-

(137)

Meaning postulate for the intermediate readings (modified version #3)

\([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{intermediate}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}} = {\uplambda }\hbox {Q}.{\uplambda }\hbox {x}{:}\,\exists \hbox {p} \in \hbox {pot(Q)}([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})\) is defined).

\(\exists \hbox {p}\in \hbox {pot(Q)}([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {x})\) is defined & \([\![\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{decl}}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {x})=1\)

& there is no \(\hbox {p}'\subset \hbox {pot(Q)}\) such that

-

\(\hbox {p}'\subset \hbox {p}\)

-

&

-

&

-

On this proposal, we get the following prediction:

-

(138)

-

Mary predicted which guests attended the party.

-

Presupposition: there is a potential basic complete answer p to ‘which guests attended the party?’ such that \([\![\hbox {predict}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {p})(\hbox {Mary})\) and \([\![\hbox {predict}]\!]^{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {exh}_{\mathrm{Q}}(\hbox {p}))(\hbox {Mary})\) are defined.

-

\(\varvec{\rightarrow }\) This is always true (because non-factive predict has no presupposition)

-

Assertion: there is a potential basic complete answer p to ‘which guests attended the party?” such that Mary predicted p and Mary did not predict any stronger basic complete answer.

-

The presupposition is vacuous. As to the assertion, it is true as soon as Mary predicted that some potential basic complete answer is true. Take indeed the strongest potential basic complete answer that Mary predicted. Such a proposition satisfies the existential statement of the assertive part of the rule. So even if the strongest potential basic answer that Mary predicted is the tautology, the sentence comes out true. In fact, the sentence ends up equivalent to Mary predicted the tautology. Assuming that predict is monotone-increasing with respect to its complement, as soon as Mary predicted something, she predicted the tautology. So the sentence is true when Mary predicted the tautology and entails that Mary predicted the tautology, hence it simply expresses the proposition that Mary predicted the tautology. Likewise, if we use non-veridical, non-factive tell, Mary told Peter who came comes out true if and only if Mary told Peter the tautology. This, we surmise, is sufficient to explain why the weakly exhaustive reading is not detected for these non-presuppositional uses of tell and predict. On some quite standard assumptions X told Y the tautology and X predicted the tautology are themselves tautologies. Even if we do not subscribe to such a view, the interpretation that results from our rule is such that the content of the embedded clause plays no role at all in the truth conditions, which may be sufficient to rule out this reading on pragmatic grounds. Finally, with be certain about, on the weakly exhaustive reading, John is certain about who came would come out equivalent to John is certain that the tautology is true, which is plausibly itself tautological.

It is important to note here that with know, or any other presuppositional predicate, the rule for intermediate readings as stated in (137) does not give rise to such trivial readings, thanks to the presuppositional part of the rule, which becomes non-vacuous for these verbs and constrains the identity of the basic complete answer that can satisfy the existential statement.Mary knows which students came is predicted to be equivalent (on the intermediate reading) to ‘Either no student came and there is no student x such that Mary believes that x came, or Mary knows, for every student who came, that these students came, and does not falsely believe, of a student who didn’t come, that he came’. But if we adopt (137), we still need to explain why, on the intermediate reading, Mary knows which students came is not judged true when Mary does not have any idea about who came and in fact no students came (this is the problem of tautological basic answers).

We would like to suggest that this judgment might itself be explained in pragmatic terms. Note that when it is common knowledge that no student came, Mary knows which students came becomes equivalent to the claim there is no student such that Mary believes that this student came (but she may have no belief at all about students). So in such a context, the sentence does not assign any knowledge to Mary. Though we cannot pin down the precise underlying pragmatic principle that would make such a use of a know deviant, it seems to us that a pragmatic explanation for this specific case is plausible—for instance, because the use of know in Mary knows Q normally licenses the inference that Mary knows something about Q. This line of explanation actually predicts that we should be able to set up a context where the sentence is in fact judged true when Mary has no knowledge whatsoever. What we need is a context where the speaker does not have the belief that no student came, but does not exclude that possibility either. On top of that, the relevant scenario must be such that the attitude bearer (the subject of know) is presented as having no false positive beliefs about the question but also as having no true negative beliefs (so that we are sure that we probe the intermediate reading). Constructing such a context and then the appropriate scenario proves pretty hard, which is in itself suggestive, as it may explain the intuition that if Mary has no knowledge whatsoever Mary knows Q is false (in fact only quite implausible contexts and scenarios seem to meet all these conditions). Nevertheless, here is an attempt to set up such a context (thanks to Danny Fox for suggesting this specific scenario):

-

(139)

Every Friday at 5 pm, the radio gives the names of the people who won the lottery. John’s father, who is old and has memory problems, listens to the radio all the time. If nobody wins, John’s father doesn’t notice that no list is read, so he does not know that nobody wins. If a list is read, he doesn’t know that it’s the complete list. But he does remember the list of the names for some time after 5 pm. On a certain day, John tells his wife at 5.05 pm: “I’ll call my father. He knows who won the lottery.”

If in fact on that day nobody won the lottery, was John’s sentence false? Our impression (and that of our informants) is that even upon learning that there was no winner and so John’s father knew nothing at all, one does not conclude that John was wrong. We conclude, very tentatively, that it might be possible to defend the proposal (137).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spector, B., Egré, P. A uniform semantics for embedded interrogatives: an answer, not necessarily the answer. Synthese 192, 1729–1784 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-015-0722-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-015-0722-4

by definition.

by definition. .

. . Symmetrically with

. Symmetrically with  , where

, where